Abstract

Background and Purpose

Stroke, increasingly referred to as a "brain attack", is one of the leading causes of death and the leading cause of adult disability in the United States. It has recently been estimated that there were three quarters of a million strokes in the United States in 1995. The aim of this study was to replicate the 1995 estimate and examine if there was an increase from 1995 to 1996 by using a large administrative claims database representative of all 1996 US inpatient discharges.

Methods

We used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, release 5, which contains ≈ 20 percent of all 1996 US inpatient discharges. We identified stroke patients by using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes from 430 to 438, and we compared the 1996 database with that of 1995.

Results

There were 712,000 occurrences of stroke with hospitalization (95% CI 688,000 to 737,000) and an estimated 71,000 occurrences of stroke without hospitalization. This totaled 783,000 occurrences of stroke in 1996, compared to 750,000 in 1995. The overall rate for occurrence of total stroke (first-ever and recurrent) was 269 per 100,000 population (age- and sex-adjusted to 1996 US population).

Conclusions

We estimate that there were 783,000 first-ever or recurrent strokes in the United States during 1996, compared to the figure of 750,000 in 1995. This study replicates and confirms the previous annual estimates of approximately three quarters of a million total strokes. This slight increase is likely due to the aging of the population and the population gain in the US from 1995 to 1996.

Introduction

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States, after heart disease and cancer, and the leading cause of adult disability.[1] In 1994, Matchar and Duncan [2] claimed that each year there are ≈ 550,000 strokes in the US, causing 150,000 deaths and leaving 300,000 survivors disabled. The Heart and Stroke Statistical Update [3,4] of the American Heart Association (1995, 1997) states that ≈ 500,000 Americans suffer a first-ever or recurrent stroke each year. All three reports were based on the predominately white cohort study of Framingham, Massachusetts. In 1998, Broderick et al [5] hypothesized that the figure of approximately half a million strokes substantially underestimates the actual annual stroke burden for the United States. They claimed that there were at least 731,000 first-ever or recurrent strokes during 1996.[5] This estimate was derived by extrapolating from first-ever strokes among whites in the Rochester, Minnesota Stroke Study. The 1999 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update [6] of the American Heart Association adjusted their estimate to ≈ 600,000 first-ever or recurrent strokes each year in the US.

Population-based stroke incidence studies such as those from Framingham, Massachusetts and Rochester, Minnesota have substantially increased the knowledge about stroke trends, subtypes, risk factors and incidence rates in both men and women. However, these studies were conducted among predominately white populations. Recently, epidemiological studies have been focusing on differences in stroke incidence between racial/ethnic groups. Of particular interest are rates for blacks; however, there is little data regarding stroke risk in Hispanics or Asians. Recent data from Northern Manhattan suggest that blacks are not alone in the higher risk category and that Hispanics also appear to be at greater risk than whites.[7]

In order to get a more accurate estimate of occurrences of stroke in the US, Williams et al [8] estimated the 1995 incidence, occurrence and characteristics of total stroke based on a large administrative claims database representative of all 1995 US inpatient discharges. They conservatively claimed that there were ≈ 750,000 first-ever or recurrent strokes during 1995.

The primary goal of this paper was to replicate the recent estimates of Broderick et al [5] and Williams et al, [8] and to examine the trend from 1995 to 1996. This was accomplished by use of a large administrative claims database representing a 20% representative sample of all 1996 US inpatient discharges. The administrative database was supplemented by appropriate adjustments for the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 430-438 derived by Williams et al [8] to correct for some of the inaccuracies of the diagnostic codes.

Subjects and Methods

Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database

This study employed the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), release 5, which is a large administrative claims database that is a 20% representative sample of all 1996 US inpatient discharges. The fifth release of the NIS contains 6.5 million discharges from a sample of 906 hospitals covering 19 geographically dispersed states. Compared to the fourth release,[8] the fifth release uses 32 fewer hospitals and contains 0.2 million fewer discharges. Similar to those of the fourth release, these data also represent a 20% stratified sample of all U.S. inpatient discharges. Stratification variables included region, control, location, teaching status and bedsize. The software program SUDAAN [9] was used to convert raw counts generated from the NIS database into weighted counts that represent national estimates.

Inpatient records included clinical and resource use information typically available from discharge abstracts. The NIS database includes most commonly used data elements: patient demographics, admission source, principal and secondary diagnoses and procedures, expected primary source of payment, discharge status, hospital and discharge weights, length of stay and total charges.

Data Analysis

We only used the first code reported to avoid double counting those patients with more than one reported ICD-9-CM code 430 to 438 at discharge. To obtain the estimated number of stroke cases by ICD-9-CM code, we multiplied the number of patients with each ICD-9-CM code by its estimated positive predictive value (PPV) for stroke.[8] The total number of hospital strokes was calculated by summing across codes. A 95% confidence interval was computed by utilizing Monte Carlo simulation techniques [10] (i.e., the PPV distribution for each code was simulated by using 10,000 iterations of a binomial distribution whose parameters were obtained by pooling data from four published ICD-9 stroke validation studies [5,11,12,13]).

Technically, an incidence rate should include only the first episode of the disease being studied. However, because this database does not distinguish between first-ever and recurrent strokes, total stroke (first-ever and recurrent) rates and occurrences were reported. Stroke (first-ever) incidence rates were estimated by reducing the total stroke rates by the expected number of recurrent strokes. The limited data from population-based cohorts suggest that 25% to 35% of strokes are recurrent.[5,14,15] Age- and sex-standardized and stratified incidence rates of total stroke were also estimated. These were estimated by using the 1996 US census population figures.[16]

Nonhospital stroke

Even though ICD-9-CM principal and secondary diagnosis codes 430 to 438 provide virtually complete ascertainment of hospital strokes, not all stroke patients are hospitalized. Two population-based stroke incidence studies, [7,17] reported that the proportion of patients with stroke without hospitalization (nonhospital strokes) was 5% and 15%, respectively.

Therefore, to estimate the total number of strokes (hospital and nonhospital), an appropriate adjustment was made in the analysis. This adjustment conservatively assumed that 10% of strokes were nonhospital strokes. This was a simple mean of the proportions published in two stroke studies (5% and 15%). Several international studies of westernized countries have reported proportions ranging from 10 to 30%.[18] The two published US proportions (5% and 15%) were also used in a sensitivity analysis.

Results

The 1996 results were compared to those of 1995 [8] (in parentheses). The NIS database contained 384,968 (377,544) patient discharges with a principal or secondary (first code reported) diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease. This was extrapolated to 2,082,005 (1,977,794) patient discharges in the United States. Table 1 uses the ICD-9 code-specific pooled PPVs [8] to adjust for false positives and reports that there were 712,000 (682,000) hospital strokes in the United States, with a 95% confidence interval of 688,000 (660,000) to 737,000 (704,000). We believe that at least 71,000 (68,000) additional strokes were nonhospital strokes, 10% of the total occurrences of stroke. We thus estimate that there were over 783,000 (750,000) incident and recurrent strokes in the United States in 1996 (1995). The sensitivity analysis on the nonhospital stroke rate produced a range from 748,000 (716,000) to 819,000 (784,000).

Table 1.

US Estimates of Number of Hospitalized Strokes by ICD-9-CM Code for Principal or Secondary Diagnoses

| ICD-9 | Definition | Estimated PPVa | Weighted count | US Estimate | US Estimate |

| in 1996 | in 1996 | in 1995b | |||

| 430 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 39/47 = 83% | 28,604 | 23,735 | 23,389 |

| 431 | Intracerebral hemorrhage | 86/101 = 85% | 87,072 | 74,141 | 71,582 |

| 432 | Other and unspecified | 1/24 = 4% | 26,129 | 1,089 | 1,031 |

| intracranial hemorrhage | |||||

| 433 | Occlusion and stenosis of | 91/607 = 15% | 368,864 | 55,299 | 51,371 |

| precerebral arteries | |||||

| 434 | Occlusion of cerebral arteries | 573/701 = 82% | 460,173 | 376,147 | 353,493 |

| 435 | Transient cerebral ischemia | 43/351 = 12% | 257,384 | 31,531 | 29,555 |

| 436 | Acute but ill-defined | 230/318 = 72% | 181,842 | 131,521 | 133,278 |

| cerebrovascular disease | |||||

| 437 | Other and ill-defined | 11/134 = 8% | 140,678 | 11,548 | 11,328 |

| cerebrovascular disease | |||||

| 438 | Late effects of cerebrovascular | 5/360 = 1% | 531,259 | 7,379 | 6,975 |

| disease | |||||

| Estimated number of | 712,390 | 682,002 | |||

| hospitalized strokes |

Of the estimated 712,000 (682,000) hospital strokes, 23,700 (23,400) or 3.3% (3.4%) were subarachnoid hemorrhages, 74,100 (71,600) or 10.4% (10.5%) were intracerebral hemorrhages, and the remaining 615,000 (587,000) or 86.4% (86.1%) were ischemic strokes.

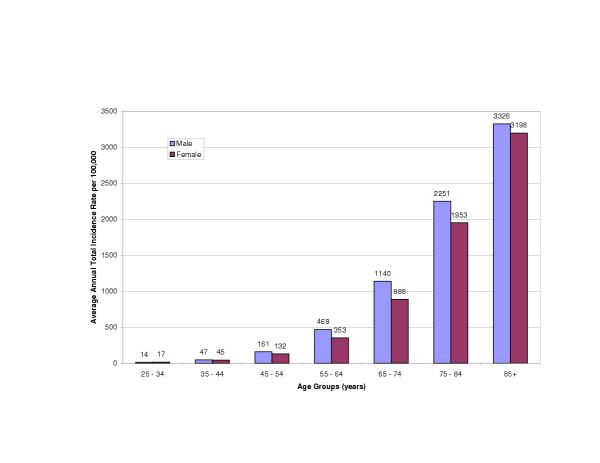

The overall incidence rate for total stroke (first-ever and recurrent) was 269 (259) per 100,000 population (age and sex-adjusted to the 1996 (1995) U.S. population). The average annual age and sex-adjusted incidence rate for first-ever stroke was estimated to be 208 (200) per 100,000. Total stroke incidence rates increased exponentially with age for both men and women. In addition, men had higher age-specific total stroke incidence rates than did women, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Average Annual Age-Specific Incidence Rates of Total Stroke (First-ever and Recurrent) Per 100,000 Population in the United States in 1996 by Sex.

Table 2 reports demographic and clinical characteristics of the stroke patients by ICD-9-CM code. The mean age of all patients with stroke was 72.1 (72.1) years, 45% (45%) were male, 80% (80%) were white, and 11% (12%) of the patients died during the hospitalization. A disproportionately low percentage of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage were male (37% [37%] versus 45% [45%]), and as expected, the patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage were much younger than the average stroke patient (56.4 [56.6] versus 72.1 [72.1] years). The inpatient mortality rates for subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhages were significantly higher than for the overall stroke population, at 27% (26%) and 28% (29%), respectively. A surprisingly high percentage of ICD-9-CM code 432 patients were male (60% [61%] versus 40% [39%]), and most code 433 patients were white (91.6% [92.5%]).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Hospitalized Stroke Patients in 1996 by ICD-9-CM Codea

| ICD-9 | Male | Mean | White | Black | Discharged | Routine | Expired | Mean Length | Mean Total | Median | Died |

| % | Age | % | % | to | Discharge | % | of Stay (days) | Charge ($) | Total | ||

| (years) | SNF, % | % | Charge | ||||||||

| 430 | 37 | 56.4 | 73.0 | 13.9 | 8 (7) | 33 (34) | 27 (26) | 13.9 (14.0) | 51,193 | $26,896 | 26% |

| (37) | (56.6) | (73.9) | (14.9) | (46,711) | |||||||

| 431 | 49 | 68.2 | 75.6 | 14.0 | 16 (15) | 23 (24) | 28 (29) | 10.3 (10.5) | 24,409 | $11,871 | 29% |

| (49) | (68.1) | (75.6) | (14.0) | (23,097) | |||||||

| 432 | 60 | 68.6 | 75.1 | 13.2 | 17 (14) | 37 (39) | 16 (15) | 10.3 (10.6) | 26,852 | $13,813 | 15% |

| (61) | (68.2) | (74.9) | (14.1) | (24,579) | |||||||

| 433 | 53 | 72.2 | 91.6 | 4.4 | 7 (6) | 72 (73) | 2 (2) | 5.5 (5.8) | 15,474 | $10,386 | 2% |

| (53) | (71.9) | (92.5) | (4.0) | (15,154) | |||||||

| 434 | 45 | 72.7 | 78.5 | 14.0 | 20 (19) | 35 (36) | 10 (10) | 9.5 (10.1) | 17,406 | $9,842 | 10% |

| (45) | (72.7) | (79.6) | (13.1) | (17,519) | |||||||

| 435 | 41 | 73.1 | 83.3 | 10.3 | 9 (9) | 73 (73) | 0.6 | 4.5 (4.9) | 8,195 | $5,736 | 0.7% |

| (42) | (73.3) | (84.0) | (10.0) | (0.7) | (8,147) | ||||||

| 436 | 43 | 74.9 | 81.3 | 13.2 | 22 (20) | 35 (36) | 11 (12) | 8.7 (11.0) | 13,789 | $7,872 | 12% |

| (43) | (74.8) | (80.8) | (14.2) | (13,771) | |||||||

| 437 | 41 | 74.4 | 83.3 | 11.1 | 21 (20) | 48 (49) | 4 (4) | 7.4 (7.9) | 12,877 | $7,662 | 4% |

| (42) | (74.6) | (84.7) | (10.0) | (12,295) | |||||||

| 438 | 47 | 73.3 | 75.2 | 16.5 | 23 (22) | 42 (43) | 5 (5) | 8.7 (9.3) | 13,068 | $8,322 | 5% |

| (47) | (73.2) | (75.5) | (16.7) | (12,806) | |||||||

| Stroke | 45 | 72.1 | 79.7 | 12.9 | 18 (17) | 39 (39) | 11 (12) | 9.0 (9.8) | 18,022 | 12% | |

| (45) | (72.1) | (80.4) | (12.6) | (17,711) | |||||||

| patients |

SNF indicates skilled nursing facility. aThe numbers in parentheses are those of 1995 and are taken from Williams et al[8], TABLE 3.

Table 2 also presents data on resource utilization. For the index hospitalization, the stroke patient population had a mean length of stay of 9.0 (9.8) days (median 5 [5] days) and a mean total charge of $18,022 (17,711) (median $8,845 [$8,735]). Patients with subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhages had much longer length of stays, averaging 13.9 (14.0) and 10.3 (10.5) days, respectively. Their mean total charges were also higher, at $51,193 ($46,711) and $24,409 ($23,097), respectively. The majority of stroke patients had a routine discharge or were discharged to a skilled nursing facility with rates of 39% (39%) and 18% (17%), respectively.

Discussion

Williams et al [8] estimated that there were 750,000 first-ever or recurrent strokes in 1995. We conservatively estimate that there were 783,000 first-ever or recurrent strokes in 1996. The 33,000 (4.4%) increase in first-ever or recurrent strokes may be due to chance, but it is probably due to the population gain (262,803,000 in 1995 versus 265,229,000 in 1996, a 0.9% increase), and the increase in aging (≥ 65 years old) population from 1995 to 1996 (33,619,000 in 1995 versus 33,957,000 in 1996, a 1.0% increase).[16] The aging population effect is more pronounced in the group aged 75+ years who are at greater risk of stroke (14,863,000 in 1995 versus 15,266,000 in 1996, a 2.7% increase).[16] We also estimate that American hospitals charged $12.4 billion for stroke treatment and management during 1996, which translates to a society cost of approximately $7 billion.

It is worthwhile to notice the remarkable consistency in stroke patient characteristics between 1995 and 1996, as shown in Table 2. The length of stay, however, was shorter in 1996 than in 1995 for stroke patients, although the total charge was higher in 1996 than in 1995. It may be due to a combination of inflation and inpatient healthcare practice changes or healthcare reimbursement regulation changes.

The present study may be associated with several limitations. First, the validity of conclusions drawn from analyses of large administrative databases depends on the accuracy of case-defining diagnostic codes. Therefore, the validity of the present study is highly dependent on the accuracy of the positive predictive values of the ICD-9-CM codes, which has been addressed.[8]

The impact of the uncertainty in the PPV pooled estimates was examined by constructing a 95% confidence interval around the number of hospital strokes. The bounds of this confidence interval were tight (688,000, 737,000), indicating that the point estimate had reasonable precision.

Another limitation of the present study is the lack of documented information on the rate of nonhospital stroke. Additional data are needed to produce a more reliable estimate of the proportion of strokes without hospitalization. By intentionally choosing a low percentage, we were confident that our estimate of the total annual stroke burden was not inflated. We used sensitivity analyses to illustrate the potential impact of a different true percentage. In addition, race-specific information was not available, which limited our ability to adjust for race.

The methodology used in the present study was the same as the one used in Williams et al, [8] but different from other studies published on the incidence, occurrence and characteristics of stroke. All those studies used state-of-the-art stroke registries based in relatively small geographical areas (Framingham, Massachusetts; Rochester, Minnesota; Rochester, New York; Northern Manhattan, New York; Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky). Our approach might have slightly reduced internal validity, but it should have far greater external validity, although this might be somewhat compromised by the reduced internal validity.

In summary, this study supports the findings of Broderick et al [5] and Williams et al [8] by conservatively estimating that there are approximately three-quarters of a million strokes each year. In addition, we observed that there is a slight increase, although not statistically significant, in occurrences of stroke from 1995 to 1996. This is likely due to a combination of the population gain and the aging of the population from 1995 to 1996.

In conclusion, stroke is a significant problem in the United States. The importance of preventive measures for a disease that has identifiable and modifiable risk factors must be emphasized. The reduction of morbidity and mortality among stroke patients must remain a public health priority.

Competing interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1471-2377-1-2-b1.pdf

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Knoll Pharmaceutical Company for funding this study.

References

- Wolf PA, Cobb JL, D'Agostino RB. Epidemiology of stroke. Barnett HJ, Stein BM, Mohr JP, Yatsu FM, eds. Stroke: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 3–27.

- Matchar DB, Duncan PW. Cost of Stroke. Stroke Clin Updates. 1994;5:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Heart and Stroke Statistical Update Dallas, Texas: American Heart Association; 1995.

- Heart and Stroke Statistical Update Dallas, Texas: American Heart. 1997.

- Broderick J, Brott T, Kothari R, Miller R, Khoury J, Pancioli R, Gebel J, Minneci L, Shukla R. The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study: Preliminary First-Ever and Total Incidence Rates of Strokes Among Blacks. Stroke. 1998;29:415–421. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart and Stroke Statistical Update Dallas, Texas: American Heart. 1999.

- Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Gan R, Chen X, Kargman DE, Shea S, Paik MC, Hauser WA, and the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study Collaborators. Stroke Incidence among White, Black and Hispanic Residents of an Urban Community. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:259–268. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GR, Jiang JG, Matchar DB, Samsa GP. Incidence and Occurrence of Total (first-ever and recurrent) Stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:2523–2528. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS. SUDAAN User's Manual, Release 75 Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1997.

- Fisher LD, van Belle G. Biostatistics: A Methodology for the Health Sciences New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1993.

- Rosamond WD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Wang CH, McGovern PG, Howard G, Copper LS, Shahar E. Stroke Incidence and Survival Among Middle-Aged Adults- 9-Year Follow-Up of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort. Stroke. 1999;30:736–743. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibson CL, Naessens JM, Brown RD, Whisnant JP. Accuracy of Hospital Discharge Abstracts for Identifying Stroke. Stroke. 1999;25:2348–2355. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.12.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benesch C, Witter DM, Wilder AL, Duncan PW, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Inaccuracy of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) in identifying the diagnosis of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Neurology. 1997;49:660–664. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar E, McGovern PG, Pankow JS, Doliszny KM, Smith MA, Blackburn H, Luepker RV. Stroke rate during the 1980's: the Minnesota Stroke Survey. Stroke. 1997;28:275–279. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RD, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD, Christianson TJ, O'Fallon WM, Wiebers DO. A population-based study of first-ever and total stroke incidence rates in Rochester, Minnesota: 1990-1994. Stroke. 2000;31:279 (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of the Census. 1996 census of population and housing. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce. 2000. http://www.census.gov/population/estimates/nation/intfile2-1.txt

- Brown RD, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD. Stroke incidence, prevalence and survival: secular trends in Rochester, Minnesota, through 1989. Stroke. 1996;27:373–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudlow CLM, Warlow CP, for the International Stroke Incidence Collaboration. Comparable studies of the incidence of stroke and its pathological types. Stroke. 1997;28:491–499. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GR, Jiang JG. Development of an Ischemic Stroke Survival Score. Stroke. 2000;31:2414–2420. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]