Abstract

Interrupted aortic arch, characterized by luminal and anatomic discontinuity between the ascending and descending aorta, is a very rare congenital malformation. The condition is typically diagnosed in neonates and is highly fatal if left untreated. Herein, we report the unusual diagnosis of an isolated type A interrupted aortic arch in a hypertensive, asymptomatic 19-year-old man.

Key words: Adult; aorta, thoracic/abnormalities/radiography; aortic arch syndromes/congenital/epidemiology/pathology; heart defects, congenital/radiography

Interrupted aortic arch is the congenital absence of anatomic and luminal continuity between the ascending and descending portions of the aorta.1,2 The anomaly was first described by the Viennese surgeon Steidele in 1778.3 With a prevalence as low as 3 in 1,000,000 live births (constituting 1% of all congenital heart disease), interrupted aortic arch is usually diagnosed and repaired during the neonatal period; it is extremely rare in adults.4 Herein, we describe the case of a man who was diagnosed with interrupted aortic arch. This patient was asymptomatic and presented with the anomaly in early adulthood, which makes the case even more unusual.

Case Report

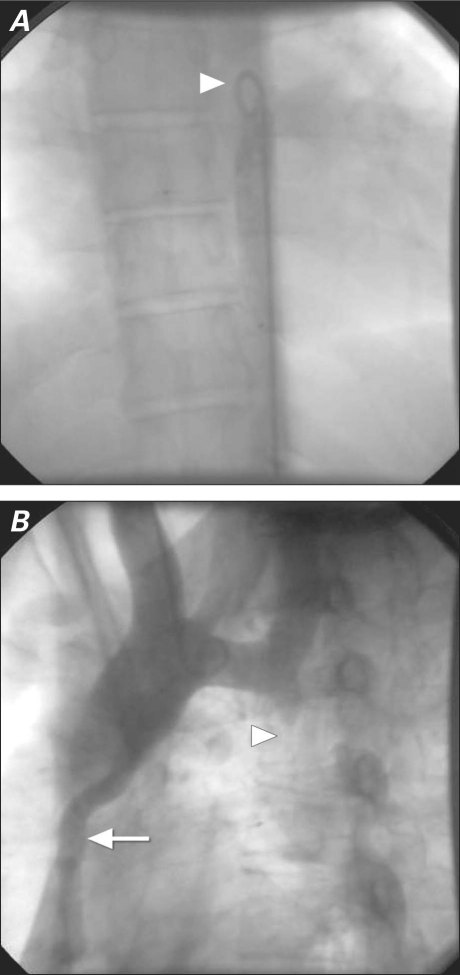

In February 2010, a 19-year-old man was referred to our center for evaluation of hypertension and diminished lower-extremity pulses. Upon his admission, the arterial blood pressure was 160/90 mmHg in both arms. The pulses were equal over both upper extremities, and radial-femoral delay was noted. The bilateral femoral and popliteal pulses were extremely weak, and the dorsalis pedis and anterior tibial pulses were impalpable. A grade 2/6 midsystolic murmur was heard on the left side of the sternum at the 2nd intercostal space and the left scapular region in the back. Results of electrocardiography were normal. A chest radiograph showed pectus excavatum. Transthoracic echocardiography showed mild aortic insufficiency, aortic valve degeneration, and concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. Because the patient's ascending aorta could not be reached through the right femoral artery, aortography was performed from the descending aorta (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, aortography from the ascending aorta through the right brachial artery showed complete interruption of the aortic arch approximately distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery (Fig. 1B). The peak systolic pressure above the interrupted segment was 180 mmHg, and the pressure below it was 100 mmHg.

Fig. 1 Aortograms after A) femoral and B) brachial arterial puncture show the site of aortic interruption (arrowheads) and the collateral vessels (arrow).

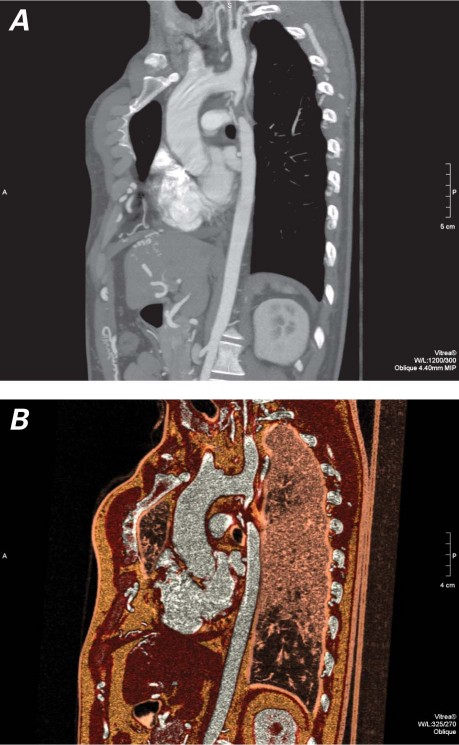

To elucidate the aortic anatomy, 64-slice computed tomographic (CT) angiography was performed. Axial and volume-rendered 3-dimensional reconstruction images clearly revealed a complete 4-cm interruption in the aortic arch, approximately 1.5 cm beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery (Fig. 2). Soft-tissue formation was observed throughout the interrupted segment. Extensive collateral vessels pervaded the interrupted aortic region from the intercostal and internal mammary arteries. The ascending and descending aortic segments were otherwise normal. The pectus excavatum deformity and minimal right ventricular compression were seen. The patient declined the recommended surgical repair.

Fig. 2 Multislice computed tomographic angiograms in A) oblique sagittal and B) oblique sagittal colored subvolume view show a type A interrupted aortic arch.

Discussion

In 1959, Celoria and Patton5 classified interrupted aortic arch into 3 types, depending upon the site of discontinuity: distal to the left subclavian artery (type A), between the left common carotid and left subclavian arteries (type B), or between the brachiocephalic and left common carotid arteries (type C). Type B interruption was most common (53%), followed by type A (43%) and type C (4%).1,5

In most patients, interrupted aortic arch is associated with additional cardiovascular anomalies, including ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, bicuspid aortic valve, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, aortopulmonary window, and truncus arteriosus. Genetic abnormalities, such as DiGeorge syndrome (chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome), have been found in 50% to 80% of patients with interrupted aortic arch.2,6 Our asymptomatic patient had an isolated type A interruption. Although the mortality rate of patients with untreated interrupted aortic arch can exceed 90% from birth to age 1 year, the anomaly can infrequently present in adulthood if substantial collateral circulation develops.1 Type B interrupted aortic arch, major associated cardiac anomalies, low birth weight, and young age at presentation are the chief risk factors for death, and the associated cardiac anomalies are the main predictor of outcome.6 In 1 study, overall survival at 16 years after study entry was found to be 59% in patients with interrupted aortic arch; the survival rate increased to approximately 70% in patients who had undergone preoperative therapy and appropriate surgical techniques.7

Interrupted aortic arch can be evaluated with use of echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although echocardiography is the primary imaging technique for characterizing cardiac abnormalities, it is not the optimal method by which to evaluate the aortic arch and descending aorta. The combination of echocardiography and MRI or CT can enable definitive diagnosis of interrupted aortic arch and associated cardiac abnormalities, as in our patient.1,2,6

In conclusion, interrupted aortic arch is rarely encountered in an adult. Echocardiography with multislice CT angiography appears to be a useful combined diagnostic imaging method in patients with this congenital anomaly. The accurate and early diagnosis of interrupted aortic arch and its associated cardiovascular anomalies is profoundly important for the patient's survival.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Murat Celik, MD, Department of Cardiology, School of Medicine, Gulhane Medical Academy, 06018 Ankara, Turkey

E-mail: drcelik00@hotmail.com

References

- 1.Dillman JR, Yarram SG, D'Amico AR, Hernandez RJ. Interrupted aortic arch: spectrum of MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;190(6):1467–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mishra PK. Management strategies for interrupted aortic arch with associated anomalies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;35 (4):569–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Steidele RJ. Sammlung verschiedener in der chirurgisch-praktischen lehrschule gemachten beobachtungen 2. Vienna: Trattern; 1778. p. 114.

- 4.Messner G, Reul GJ, Flamm SD, Gregoric ID, Opfermann UT. Interrupted aortic arch in an adult: single-stage extra-anatomic repair. Tex Heart Inst J 2002;29(2):118–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Celoria GC, Patton RB. Congenital absence of the aortic arch. Am Heart J 1959;58(3):407–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Yang DH, Goo HW, Seo DM, Yun TJ, Park JJ, Park IS, et al. Multislice CT angiography of interrupted aortic arch. Pediatr Radiol 2008;38(1):89–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McCrindle BW, Tchervenkov CI, Konstantinov IE, Williams WG, Neirotti RA, Jacobs ML, et al. Risk factors associated with mortality and interventions in 472 neonates with interrupted aortic arch: a Congenital Heart Surgeons Society study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129(2):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed]