Abstract

Background

Clinical studies have shown that rose hip powder (RHP) alleviates osteoarthritis (OA). This might be due to anti-inflammatory and cartilage-protective properties of the complete RHP or specific constituents of RHP. Cellular systems (macrophages, peripheral blood leukocytes and chondrocytes), which respond to inflammatory and OA-inducing stimuli, are used as in vitro surrogates to evaluate the possible pain-relief and disease-modifying effects of RHP.

Methods

(1) Inflammatory processes were induced in RAW264.7 cells or human peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) with LPS. Inflammatory mediators (nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and cytokines/chemokines) were determined by the Griess reaction, EIA and multiplex ELISA, respectively. Gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. RHP or its constituent galactolipid, GLGPG (galactolipid (2S)-1, 2-di-O-[(9Z, 12Z, 15Z)-octadeca-9, 12, 15-trienoyl]-3-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl glycerol), were added at various concentrations and the effects on biochemical and molecular parameters were evaluated. (2) SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells and primary human knee articular chondrocytes (NHAC-kn) were treated with interleukin (IL)-1β to induce in vitro processes similar to those occurring during in vivo degradation of cartilage. Biomarkers related to OA (NO, PGE2, cytokines, chemokines, metalloproteinases) were measured by multiplex ELISA and gene expression analysis in chondrocytes. We investigated the modulation of these events by RHP and GLGPG.

Results

In macrophages and PBL, RHP and GLGPG inhibited NO and PGE2 production and reduced the secretion of cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12) and chemokines (CCL5/RANTES, CXCL10/IP-10). In SW1353 cells and primary chondrocytes, RHP and GLGPG diminished catabolic gene expression and inflammatory protein secretion as shown by lower mRNA levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-13), aggrecanase (ADAMTS-4), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-2, MIP-3α), CCL5/RANTES, CXCL10/IP-10, IL-8, IL-1α and IL-6. The effects of GLGPG were weaker than those of RHP, which presumably contains other chondro-protective substances besides GLGPG.

Conclusions

RHP and GLGPG attenuate inflammatory responses in different cellular systems (macrophages, PBLs and chondrocytes). The effects on cytokine production and MMP expression indicate that RHP and its constituent GLGPG down-regulate catabolic processes associated with osteoarthritis (OA) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA). These data provide a molecular and biochemical basis for cartilage protection provided by RHP.

Background

A primary feature of arthritis, in particular osteoarthritis (OA), is the degradation and erosion of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in cartilage. The preceding alterations of collagen and proteoglycan implicate the activation of enzymatic systems, i.e. matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) and aggrecanase (e.g. a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type I motif, ADAMTS) [1,2]. Specifically, MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-13 cleave ECM collagen [3-5]. Interleukin (IL)-1β is considered a key catabolic factor that induces ECM degradation (reviewed in [6]). IL-1β has multiple effects on the expression of chondrocyte genes and affects matrix enzymes, chemokines and cytokines. Some of these effects are opposed by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) or bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-2 [7]. Nitric oxide (NO) has been identified as another agent in OA (reviewed in [8,9]): the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and the production of NO correlate with patho-physiological changes in chondrocytes [10-13]. The importance of chemokines in OA was highlighted by the observation that numerous chemokines and their receptors were massively induced by IL-1β in chondrocytes [7,14-16]. This underscores the importance of cell recruitment during inflammatory processes in OA.

Natural substances may attenuate the onset and progression of OA. Clinical studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of rose hip powder (RHP) in the treatment of OA [17-19] (for reviews see [20,21]). The underlying bioactive constituents of RHP remain elusive, although its known constituents such as ascorbic acid, polyphenols, flavonoids and unsaturated fatty acids presumably contribute to alleviate OA. More specifically, GLGPG, a galactolipid isolated from RHP, inhibited chemotaxis of neutrophils [17,18]. Also, RHP extracts and unsaturated fatty acids thereof inhibited cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 activity [22,23] and could partially account for the efficacy of RHP in the treatment of OA. Yet, RHP and/or its constituents have not been directly tested in chondrocytes. In this study, the effects of RHP and one of its constituent galactolipid, GLGPG, have been evaluated on (1) the production of inflammatory mediators by macrophages and peripheral blood leukocytes, and (2) anabolic and catabolic processes in chondrocytes.

Methods

Reagents

RHP, prepared from dried Rosa canina fruits of a selected cultivar, was obtained from Hyben Vital, Langeland, Denmark. GLGPG (galactolipid (2S)-1, 2-di-O-[(9Z, 12Z, 15Z)-octadeca-9, 12, 15-trienoyl]-3-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl glycerol, abbreviated as GOPO in [18]) was isolated from a lipophilic extract prepared from leaves of Valeriana locusta or from RHP (performed by AnalytiCon Discovery, Potsdam, Germany). Compounds were dissolved in DMSO and added to the culture medium concomitantly with the stimulating agent. Final DMSO concentration in culture medium in all treatments .was 0.5%. E. coli LPS (serotype 055:B5) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Sigma (Saint-Louis, MO). RPMI 1640, DMEM, 2-mercaptoethanol and MEM non-essential amino acids (NEAA) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Human IL-1β and recombinant interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were from PeproTech EC (London, UK).

Cell culture

Murine RAW264.7 macrophage cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.1 mM NEAA (DMEM-C) and 10% FBS. Cells were seeded into 12-well or 96-well plates at 1 and 0.05 × 106 cells per well, respectively, and used after 2 days of pre-culture. Cells were starved for 18 h in DMEM-C containing 0.25% FBS before the start of treatment and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4-24 h in phenol red-free DMEM-C containing 0.25% FBS.

Peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) were obtained from healthy male and female donors (Blood Donor Service, University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland). Human primary cell protocols were approved by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (No. A050573/2 to J. Schwager). Erythrocytes were removed by the Dextran sedimentation procedure [24]. Cell viability was determined by the Trypan Blue exclusion test and exceeded 95%. PBL (at 3-8 × 106 cells/mL) were cultured in phenol-red free RPMI 1640, supplemented with 0.25% FBS, 0.1 mM NEAA, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin and 5 × 10-5 M 2-mercaptoethanol. Cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 U/mL) for 2-24 h.

SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells were from ATCC and cultured in DMEM-C containing 10% FBS. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 0.5 × 106 cells per well. Sub-confluent cell monolayers were washed and incubated overnight in DMEM-C containing 0.25% FBS and 0.2% lactalbumin hydrolysate (Bacto™ LC, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Cells were activated with 10 ng/mL IL-1β in phenol-red free DMEM-C supplemented with 0.25% FBS and 0.2% lactalbumin hydrolysate in the presence of increasing concentrations of test compounds for 4-24 h. Batches of normal human articular chondrocytes from knee (NHAC-kn) obtained from different individuals were from Lonza and cultured in chondrocyte growth medium (Lonza, Wakersville, MD). For experiments NHAC-kn were used at passage 3 to 6. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 0.5 × 106 cells per well and activated with IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 4-24 h.

Cells were lysed in RLT buffer (Qiagen) after 2-4 h of culture and total RNA was extracted. Culture supernatants were harvested after 24 h of culture and stored at -80°C until use for analysis.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as previously described [25]. RNA quality and quantity was assessed by Nanodrop® ND-1000 and evaluated by the ND-1000 3.2.1 software (Witec AG, Littau, Switzerland).

Total RNA was transcribed into first strand cDNA using the Superscript™ First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) [25]. Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the ABI PRISM® 7700 Sequence Detection System or the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems [ABI], Foster City, CA). Primers and probes were designed with the Primer Express™ software purchased from ABI. PCR was performed using the Taqman® universal PCR Master Mix (ABI). 18S rRNA primers and probes were used as internal standards. Relative gene expression quantification was performed by subtracting threshold cycles (CT) for ribosomal RNA from the CT of the targeted gene (ΔCT). Relative mRNA levels were then calculated as 2-ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT refers to the ΔCT of unstimulated minus treated cells. The values were obtained from at least three independent series of experiments, in which each treatment was performed in duplicate with each being analyzed twice in RT-PCR.

Multiparametric analysis of cytokines, chemokines and interleukins

Multiparametric kits were obtained from BIO-RAD Laboratories (Hercules, CA) and used in the LiquiChip Workstation IS 200 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The data were evaluated with the LiquiChip Analyser software (Qiagen). In all experimental series, the proteins secreted into the culture supernatants were determined.

Measurement of nitric oxide and PGE2 determination

The concentration of NO in culture supernatants was measured using the Griess Reaction [26]. Secreted PGE2 was determined by Enzyme Immuno Assay (EIA) (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Harbor, WI).

Statistical analysis

Data were obtained from at least three independent series of experiments and presented as means +/- SD (in ELISA). p values < 0.05 (calculated by Student's t test or one way ANOVA) were considered statistically significant.

Results

Rose hip and GLGPG inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators by murine macrophages

Macrophages represent a cellular model to identify effects of substances on inflammatory processes including those associated with arthritis. RAW264.7 cells responded to LPS-stimulation by producing inflammatory mediators (e.g. NO and PGE2). In unstimulated cells, test substances alone did not modulate the secretion of inflammatory mediators. In LPS-treated cells, RHP reduced NO production and PGE2 secretion at IC50 values of 797 mg/L and 594 mg/L, respectively (Table 1). Similarly, GLGPG significantly inhibited the NO production (IC50 values of 28.6 mg/L), whereas PGE2 secretion was diminished by 14 ± 9% at 38.7 mg/L (i.e. highest concentration tested). The data are consistent with the described effects of rose hip constituents on the activity of COX isozymes [22,23]. At the investigated concentrations, RHP or GLGPG did not impair cell viability as determined by LDH release (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on NO and PGE2 production in RAW264.7 cells

| Substance | IC50 ± SEM (NO) [mg/L] | IC50 ± SEM (PGE2) [mg/L] |

|---|---|---|

| GLGPGa | 28.6 ± 4.6 (N = 6) | > 38.7c (N = 6) |

| RHPb | 796.9 ± 36.9 (N = 15) | 594 ± 43 (N = 14) |

LPS-stimulated cells were cultured for 24 h with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP, or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L GLGPG. The concentration of NO and PGE2 was determined in culture supernatants and the IC50 values (± SEM, standard error of the mean) were computed. N, number of independent experimental series. At the conditions described in Materials and Methods, unstimulated and LPS-stimulated cells produced < 0.125 μM nitrite and 25.4 ± 1.2 μM, respectively.

aGLGPG: galactolipid (2S)-1, 2-di-O-[(9Z, 12Z, 15Z)-octadeca-9, 12, 15-trienoyl]-3-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl glycerol; MW 774

bFrom Hyben Vital

c Highest concentration of GLGPG tested. At 38.7 mg/L GLGPG, PGE2 production was inhibited by 14 ± 9%.

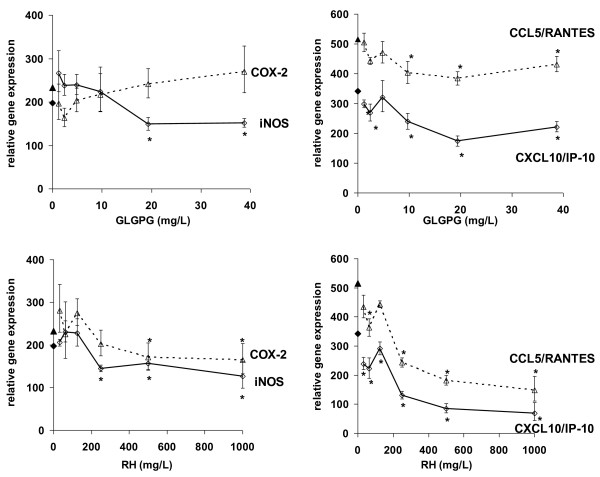

LPS-stimulation of RAW264.7 elicited the expression of inflammatory genes. Most (e.g. genes for TNF-α, COX-2, iNOS, IL-1α, CCL5/RANTES, CXCL10/IP-10) were drastically up-regulated (Table 2 and Additional File 1). We had determined in previous experiments that at 2, 4 and 8 h of stimulation, LPS-responding genes were significantly up-regulated (data not shown); at 4 h both early- and late-responding genes were significantly expressed. At this point in time, the iNOS mRNA levels were concentration-dependently reduced by GLGPG and RHP (Figure 1). COX-2 mRNA levels were not affected, but those of prostaglandin E synthase (PGES), which converts PGH2 to PGE2, were lowered (Table 2 and Additional File 1). Among murine cytokines and chemokines, CCL5/RANTES and CXCL10/IP-10 were robustly down-regulated by RHP and GLGPG. The expression of MMP-9 was also significantly reduced by RHP and less profoundly by GLGPG. Remarkably, expression of the anti-inflammatory IL-10 was increased by both substances. Macrophage genes encoding transcription factor (TF) of the NF-κB signaling pathway (i.e. NF-κB1, NF-κB49, NF-κBp65, I-κBα) were up-regulated by LPS (Table 2 and Additional file 1). RHP significantly reduced all TFs towards pre-stimulation values or below. GLGPG had less robust effects on those factors and markedly reduced only NF-κB49. Thus, the test compounds modulated gene expression at the transcriptional level via elements of the NF-κB pathway.

Table 2.

Modulation of gene expression in RAW264.7 cells by RHP and GLGPG

| Gene | CTa | LPS | LPS + RHP (250 mg/L) | LPS + GLGPG (9.7 mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fold change | fold change | p valueb | fold change | p valueb | ||

| TNF-α | 22.9 | 29.6 | 21.8 | 0.0001 | 20.4 | 0.002 |

| COX-2 | 27.5 | 247 | 203.3 | 0.347 | 217 | 0.660 |

| PGES | 33.0 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.0107 | 2.0 | 0.214 |

| iNOS | 29.9 | 197 | 239.4 | 0.041 | 224 | 0.357 |

| IL-1α | 33.7 | 22081 | 8128 | 0.0115 | 18501 | 0.087 |

| IL-10 | 38.3 | 66.8 | 176 | < 0.0001 | 78.6 | 0.074 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 29.7 | 515 | 121 | < 0.0001 | 403 | 0.003 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | 27.2 | 342 | 65.4 | 0.0001 | 239 | 0.021 |

| NF-κB1 | 24.8 | 6.3 | 2.1 | 0.0002 | 6.0 | 0.366 |

| NF-κB49 | 25.3 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 0.0028 | 3.7 | 0.028 |

| NF-κBp65 | 23.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.0045 | 1.1 | 0.126 |

| I-κBα | 24.4 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 0.0004 | 5.7 | 0.391 |

| CD14 | 24.9 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.198 | 1.4 | 0.012 |

| MMP-9 | 29.0 | 6.8 | 3.0 | 0.0493 | 7.8 | 0.145 |

LPS-stimulated cells were cultured with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 4 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. Fold changes were calculated as indicated in Materials and Methods. Only the effects of 250 mg/L RHP and 9.7 mg/L GLGPG are shown.

aCT = cycle threshold (CT < 22 = high basal gene expression; 23 < CT < 30 = intermediate basal gene expression; CT > 30 = low basal gene expression).

bp value = significance value between (LPS)- and (LPS + compound)-treatment.

Figure 1.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in RAW264.7 cells. Expression levels of COX-2, iNOS, CCL5/RANTES and CXCL10/IP-10 in RAW264.7 cells stimulated with LPS for 4 h in the presence of 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L (i.e 1.25 -50 μmol/L) of GLGPG (upper panels) or 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP (lower panels). Relative gene expression refers to 2-ΔΔCT (see Materials and Methods). Filled symbols on the y-axis indicate the values observed in LPS-stimulated cells (without test substances). * p < 0.05.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on peripheral blood leukocytes

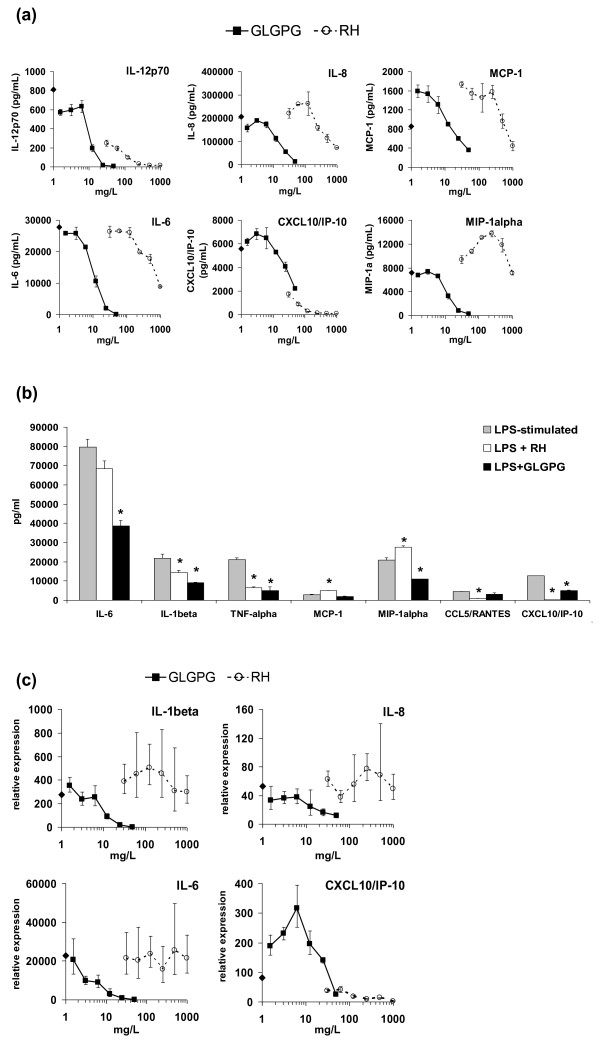

Orally absorbed bioactive compounds reach target tissues via the vascular system, where they might exert effects on peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL). Therefore, the effects of RHP and GLGPG on LPS/IFN-γ -activated PBL was investigated. The secretion of chemokines or interleukins was modulated by RHP and GLGPG in an idiosyncratic pattern (Table 3; Figure 2a-b and Additional file 2). RHP significantly reduced the production of CXCL10/IP-10 and CCL5/RANTES; the levels of other chemokines were unaltered or only affected at the highest tested RHP concentrations (Figure 2a). GLGPG reduced MCP-1 and MIP-1α secretion. It did, however, not match the effect of RHP on CXCL10/IP-10 and CCL5/RANTES production. RHP had robust effects on secretion levels of (pro-inflammatory) IL-12p70 and (anti-inflammatory) IL-10, while it modulated IL-1β and IL-6 less profoundly. This contrasted with the effects of GLGPG, which significantly diminished IL-1β and IL-6 (Figure 2b). TNF-α and IFN-γ were concentration-dependently diminished by both RHP and GLGPG (Figure 2b, Table 3). Furthermore, in PBL RHP increased the expression of GM-CSF, an anabolic factor for chondrocytes [27]. Next, expression levels of inflammatory mediators were determined in human PBL. In most cases, RHP and GLGPG exerted effects on mRNA levels that paralleled those described for the secreted proteins (Table 4, Figure 2c and Additional file 3). In particular, RHP robustly down-regulated mRNA levels of IL-1α, TNF- α and CXCL10/IP-10, but not those of e.g. IL-6, CCL5/RANTES, COX-2, MIP-2 or MIP-3α. Other genes that are involved in the production of eicosanoids (e.g. 5-lipoxygenase) or participate in ECM remodeling (e.g. MMP-9) were not modulated by the test compounds. The results infer that the main effects of the natural substances were at the transcriptional rather than the post-transcriptional level. A notable exception was CCL5/RANTES, where mRNA levels were barely up-regulated by LPS/IFN-γ stimulation, while the secretion of CCL5/RANTES was impaired by the natural substances.

Table 3.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on the production of chemokines and cytokines in human PBL

| Protein | Ratioa | LPS/IFN-γ | LPS/IFN-γ + RHP (250 mg/L) | LPS/IFN-γ + GLGPG (9.7 mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pg/mL ± SD | pg/mL ± SD | p valueb | pg/mL ± SD | p valueb | ||

| Eotaxin | 28 | 84 ± 2 | 62 ± 6 | 0.037 | 62 ± 3 | 0.013 |

| MCP-1 | 497 | 2940 ± 226 | 4990 ± 71 | 0.007 | 1880 ± 368 | 0.074 |

| MIP-1β | 169 | 90900 ± 1838 | 109009 ± 1823 | 0.005 | 47550 ± 3465 | 0.004 |

| MIP-1α | 2092 | 21079 ± 1131 | 27510 ± 849 | 0.023 | 10950 ± 71 | 0.006 |

| IL-8 | 794 | 325103 ± 12738 | 433040 ± 122728 | 0.059 | 267052 ± 36770 | 0.255 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 14 | 4470 ± 57 | 1011 ± 55 | < 0.001 | 3210 ± 750 | 0.067 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | 47 | 12650 ± 16 | 150 ± 16 | 0.002 | 5025 ± 148 | 0.005 |

| IL-1β | > 2000 | 21900 ± 2121 | 14350 ± 1344 | 0.051 | 9195 ± 106 | 0.014 |

| IL-6 | > 2000 | 79650 ± 4031 | 68450 ± 4031 | 0.083 | 38604 ± 2828 | 0.005 |

| IL-12(p70) | > 200 | 295 ± 2 | 19 ± 2 | 0.002 | 69 ± 17 | 0.006 |

| IL-10 | 67 | 233 ± 8 | 382 ± 3 | 0.002 | 143 ± 47 | 0.118 |

| TNF-α | > 2000 | 21107 ± 990 | 6595 ± 290 | 0.003 | 5105 ± 1775 | 0.008 |

| IFN-γ | 672 | 2065 ± 106 | 226 ± 18 | 0.002 | 475 ± 2 | 0.002 |

| GM-CSF | 158 | 148 ± 5 | 190 ± 47 | 0.329 | 54 ± 2 | 0.002 |

LPS/IFN-γ -stimulated cells were cultured with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 24 h and proteins were quantified by multiparametric analysis (see Materials and Methods). Only the effects of 250 mg/L RHP and 9.7 mg/L GLGPG are shown.

a protein secreted by stimulated/protein secreted by unstimulated cells

b p value = significance value between (LPS/IFN-γ)- and (LPS/IFN-γ + substance) -treatment.

Figure 2.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on inflammatory mediators in PBL. (a) Proteins secreted by PBLs during LPS/IFN-γ stimulation for 24 h without (symbol on the y axis) or with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG. (b) Effects of RHP (250 mg/L) and GLGPG (9.7 mg/L) on the secretion of interleukins and chemokines by LPS/IFN-γ stimulated PBL that were cultured for 24 h. Asterisks indicate statistical significant differences in comparison to LPS-stimulated cells (* p < 0.05). (c) Expression levels of interleukins (IL-1β and IL-6) and chemokines (IL-8, CXC10/IP-10) in LPS/IFN-γ stimulated PBL cultured for 2 h with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG. The symbol on the y-axis indicates the LPS/IFN-γ -induced increase in mRNA levels, in the absence of test compounds.

Table 4.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in human PBL

| Gene | CTa | LPS/IFN-γ | LPS/IFN-γ + RHP (250 mg/L) | LPS/IFN-γ + GLGPG (9.7 mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fold change | fold change | p valueb | fold change | p valueb | ||

| COX-2 | 22.8 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 0.880 | 6.8 | 0.16 |

| TNF-α | 24.9 | 16.1 | 8.9 | 0.004 | 12.4 | 0.04 |

| IL-1α | 27.2 | 17.9 | 11.3 | 0.002 | 16.1 | 0.37 |

| IL-6 | 29.8 | 54.8 | 43.6 | 0.254 | 55.6 | 0.94 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 25.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.908 | 1.3 | 0.45 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | 35.5 | 1444 | 190 | < 0.001 | 2340 | 0.04 |

| MIP-2 | 28.6 | 16.8 | 18.7 | 0.577 | 15.6 | 0.66 |

| MIP-3α | 28.7 | 37.6 | 32.3 | 0.159 | 23.1 | 0.01 |

| 5-LOX | 25.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.018 | 0.8 | 0.96 |

| MMP-9 | 27.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.830 | 0.8 | 0.81 |

LPS/IFN-γ -stimulated cells were cultured with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 2 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. Fold changes were calculated as indicated in Materials and Methods. Only the effects of 250 mg/L RHP and 9.7 mg/L GLGPG are shown.

aCT = cycle threshold (CT < 25 = high basal gene expression; 25 < CT < 30 = intermediate basal gene expression; CT > 30 = low basal gene expression).

bp value = significance value between (LPS/IFN-γ)- and (LPS/IFN-γ + substance) -treatment

Rose hip and GLGPG modulate catabolic gene expression in chondrosarcoma SW1353 cells

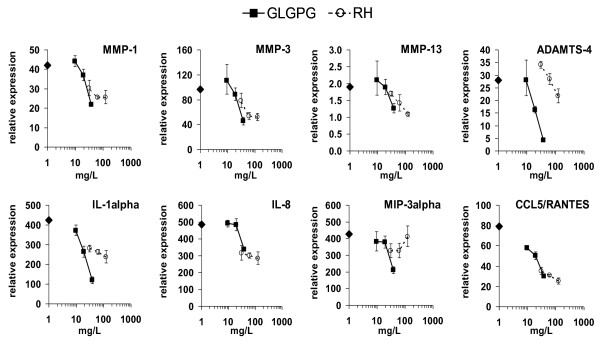

The chondrosarcoma SW1353 cell line was used as a surrogate for primary chondrocytes. In response to exogenous IL-1β, these cells altered the expression of a similar set of genes as primary chondrocytes [28] (Tables 5 and 6). IL-1β activated SW1353 cells displayed increases in gene expression levels of MMP-1, -3, -13 and ADAMTS-4. In contrast, MMP-2 and ADAMTS-5 were barely affected. Treatment of IL-1β-activated SW1353 cells with RHP or GLGPG led to a significant inhibition of gene expression of MMP-1, -3, -13 but not of ADAMTS-4 or MMP-2 (Table 5). IL-1β treatment only slightly influenced expression levels of anabolic genes (i.e. aggrecan, collagen), whereas other mediators such as COX-2, TNF-α, iNOS, IL-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) [14,29] were markedly altered by IL-1β stimulation (see fold changes in Table 5). Basal chemokine gene expression was low in SW1353 cells; IL-1β treatment induced dramatic increases of chemokine mRNA levels, with CCL5/RANTES and MIP-3α being the most responsive. RHP significantly decreased the expression levels of five chemokine genes (MIP-2, MIP-3α, IL-8, CCL5/RANTES and CXCL10/IP-10) (Table 5) and cytokine genes including IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-6. Whereas GLGPG significantly reduced CXCL10/IP-10 expression, it augmented that of MIP-2 or IL-8. This feature was also observed with regard to anabolic genes, where GLGPG, in contrast to RHP, increased aggrecan and collagen expression. It should be stressed that the chosen in vitro conditions preferably trigger catabolic activity in chondrocytes, while anabolic events would have been favored at different culture conditions.

Table 5.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in human chondrosarcoma SW1353 cells

| Gene | CTa | IL-1β | IL-1β + RHP (250 mg/L) | IL-1β + GLGPG (9.7 mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fold change | fold change | p valueb | fold change | p valueb | ||

| MMP-1 | 27.2 | 6.3 | 3.6 | 0.002 | 4.5 | 0.019 |

| MMP-2 | 22.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.006 | 1.0 | 0.142 |

| MMP-3 | 32.7 | 182.7 | 80.6 | < 0.001 | 137.0 | 0.003 |

| MMP-9 | 31.8 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 0.285 | 10.7 | 0.001 |

| MMP-13 | 28.4 | 17.7 | 8.9 | < 0.001 | 12.7 | 0.005 |

| ADAMTS-4 | 35.3 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 0.136 | 9.6 | 0.026 |

| ADAMTS-5 | 31.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.476 | 1.4 | 0.006 |

| TIMP-1 | 21.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.195 | 1.9 | 0.007 |

| Aggrecan | 32.0 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.017 | 3.7 | < 0.001 |

| Collagen I | 19.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.028 | 1.8 | 0.001 |

| COL2A1 | 31.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.001 | 0.9 | 0.526 |

| MIP-2 | 40.2 | 1169 | 474 | < 0.001 | 1626 | 0.006 |

| MIP-3α | 38.5 | 19642 | 12001 | < 0.001 | 20822 | 0.437 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 42.9 | 35920 | 27081 | 0.048 | 41476 | 0.353 |

| IL-8 | 34.5 | 12022 | 5599 | < 0.001 | 16308 | 0.001 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | 39.7 | 3274 | 836 | 0.001 | 1436 | 0.001 |

| IL-1α | 37.7 | 42.3 | 29.9 | 0.036 | 32.0 | 0.065 |

| IL-1β | 31.9 | 135.3 | 118.1 | 0.195 | 100.8 | 0.012 |

| IL-6 | 38.4 | 10846 | 5969 | 0.001 | 8876 | 0.122 |

| IL-1Ra | 31.9 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.381 | 1.7 | 0.111 |

| IL-1RI | 27.1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.001 | 1.7 | 0.885 |

| TNF-α | 34.5 | 319.2 | 705.1 | 0.001 | 567.8 | 0.003 |

| iNOS | 35.4 | 17.6 | 22.4 | 0.139 | 21.2 | 0.236 |

| COX-2 | 34.4 | 23.4 | 19.0 | 0.080 | 35.3 | 0.005 |

| LIF | 30.1 | 64.8 | 53.9 | 0.118 | 42.1 | 0.005 |

IL-1β -stimulated cells were cultured with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 4 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. Fold changes were calculated as indicated in Materials and Methods. Only the effects of 250 mg/L RHP and 9.7 mg/L GLGPG are shown.

aCT = cycle threshold (CT < 22 = high basal gene expression; 23 < CT < 30 = intermediate basal gene expression; CT > 30 = low basal gene expression).

bp value = significance value between (IL-1β)- and (IL-1β + substance) -treatment.

Table 6.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in NHAC-kn cells

| Gene | CTa | IL-1β | IL-1β + RHP (250 mg/L) | IL-1β + GLGPG (9.7 mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fold change | fold change | p valueb | fold change | p valueb | ||

| MMP-1 | 29.5 | 22.8 | 10.4 | 0.008 | 20.0 | 0.418 |

| MMP-2 | 23.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.249 | 0.8 | 0.332 |

| MMP-3 | 28.1 | 167 | 89 | 0.048 | 128 | 0.135 |

| MMP-9 | 29.6 | 7.2 | 6.0 | 0.025 | 5.0 | 0.203 |

| MMP-13 | 28.1 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.048 | 2.0 | 0.135 |

| ADAMTS-4 | 29.5 | 20.0 | 21.7 | 0.460 | 14.6 | 0.103 |

| ADAMTS-5 | 21.7 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.011 | 1.7 | 0.148 |

| TIMP-1 | 17.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.052 | 1.1 | 0.215 |

| Aggrecan | 28.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.196 | 1.1 | 0.340 |

| Collagen 1 | 18.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.8 | 0.30 |

| COL2A1 | 22.2 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.137 | 1.2 | 0.325 |

| MIP-2 | 29.9 | 441 | 110 | 0.082 | 626 | 0.147 |

| MIP-3α | 30.0 | 481 | 271 | 0.007 | 436 | 0.126 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 26.7 | 87 | 42.0 | 0.009 | 54 | 0.046 |

| IL-8 | 26.3 | 799 | 168 | 0.002 | 760 | 0.356 |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | ndc | |||||

| IL-1β | 31.3 | 1078 | 530 | 0.002 | 505 | 0.085 |

| IL-6 | 29.8 | 2011 | 1048 | 0.069 | 1927 | 0.226 |

| IL-1Ra | 28.4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.107 | 1.2 | 0.272 |

| IL-1RI | 22.6 | 0.9 | 0.5 | < 0.001 | 0.8 | 0.301 |

| TNF-α | ndc | |||||

| iNOS | ndc | |||||

| COX-2 | 26.58 | 133 | 48.3 | 0.11 | 186 | 0.03 |

| LIF | 23.8 | 35.2 | 19.2 | 0.003 | 28.9 | 0.239 |

IL-1β -stimulated cells were cultured with 31.3 - 1000 mg/L RHP or 1.2 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 4 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. Fold changes were calculated as indicated in Materials and Methods. Only the effects of 250 mg/L RHP and 9.7 mg/L GLGPG are shown.

aCT = cycle threshold (CT < 22 = high basal gene expression; 23 < CT < 30 = intermediate basal gene expression; CT > 30 = low basal gene expression).

bp value = significance value between (IL-1β)- and (IL-1β + substance) -treatment

cnd = not done

Modulation of catabolic gene expression in primary human articular chondrocytes

Normal human articular chondrocytes from knee (NHAC-kn) were activated by IL-1β in the presence of increasing concentrations of RHP or GLGPG. Basal expression levels of the monitored genes were comparable in SW1353 and NHAC-kn except for ADAMTS-5, collagen 2A1, four chemokine genes and IL-6, which were more expressed in NHAC-kn (Tables 5 and 6). The IL-1β induced changes in NHAC-kn gene expression levels were as marked as those observed in SW1353 cells. IL-1β significantly up-regulated catabolic genes (ADAMTS-4, MMP-1 and MMP-3), interleukins (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines (IL-8, CCL5/RANTES, MIP-2 and MIP-3α) and COX-2 (Table 6). LIF experienced strong up-regulation by IL-1β, a feature that was not shared by the receptor for IL-1 (IL-1RI) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra). The patho-physiological stimulus (i.e. IL-1β) weakly affected anabolic genes like collagen 1, collagen 2 and aggrecan (Table 6).

RHP significantly diminished the expression level of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-13, but had only moderate effects on ADAMTS-4, TIMP-1 or ADAMTS-5 (Table 6). Similarly, MIP-2, MIP-3α, CCL5/RANTES and IL-8 were down-regulated by up to 75%. The effects on IL-1β, IL-1RI, and IL-6 were also statistically significant. In contrast, GLGPG weakly influenced mRNA levels of most of the tested genes (p value ~0.1). The effects of the substances were concentration-dependent (Figure 3). It should be noted that RHP had more potent effects on gene expression in NHAC-kn than in PBL (Figure 2). Anabolic genes were barely altered at 4 h of IL-1β stimulation.

Figure 3.

Effect of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in chondrocytes. IL-1β-stimulated NHAC-kn were cultured for 4 h with 62.5 - 250 mg/L RHP or 9.7 - 38.7 mg/L of GLGPG and expression of the indicated genes was quantified by RT-PCR. Symbols on the y axis indicate the gene expression in IL-1β stimulated NHAC-kn (relative to unstimulated NHAC-kn).

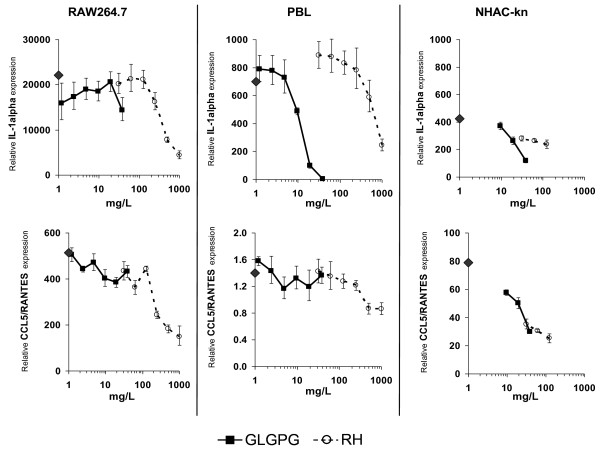

Distinct reactivity of different cell types to RHP and GLGPG

Murine macrophages, human PBLs and chondrocytes revealed idiosyncratic patterns of reactivity to RHP and GLGPG as exemplified for IL-1α and CCL5/RANTES (Figure 4). Treatment of cells with LPS and IL-1β, respectively, elicited tissue-specific responses; IL-1α was induced in all three cell populations. Concomitantly, the effect of test compounds was robust with RHP being more potent than GLGPG. Conversely, CCL5/RANTES induction was strong in RAW264.7 cells and NHAC-kn but virtually absent in PBL. In general, RHP and GLGPG had effects on genes that were strongly activated by IL-1β or LPS; conversely, non-induced genes were virtually unaffected.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the effects of RHP and GLGPG on murine macrophages, human PBL and chondrocytes. The symbols on the y-axis indicate gene expression levels in stimulated cells in the absence of substances. Cells were cultured for 4 h (RAW264.7; NHAC-kn) or 2 h (PBL).

Discussion

In this study, a panel of biological properties of rose hip powder and its constituent galactolipids, GLGPG, has been described for the first time and provides evidence that cellular parameters related to cartilage destruction and inflammatory responses were modulated by these natural compounds. This feature has been established using two approaches: (1) effects on inflammatory processes including cytokines and chemokines were monitored in macrophages and peripheral blood leukocytes, (2) modulation of catabolic activity and the production of chemokines and cytokines were determined in SW1353 cells and NHAC-kn in vitro.

An adequate homeostasis between anabolic and catabolic events ensures tissue rebuilding and renewal in intact cartilage [1]. Growth factors including insulin-growth factors, connective-tissue growth factors, TGF-β or BMP favor proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and the synthesis of collagen and aggrecan. Conversely, inflammatory factors (e.g. pro-inflammatory interleukins, eicosanoids and nitric oxide) and proteinases (e.g. MMPs and ADAMTS) induce tissue erosion and degrade ECM components, respectively. MMP-1 and -13 preferably cleave type II collagen [4]. MMP-3 has broader substrate specificity; ADAMTS-4 and -5 cleave proteoglycans [30]. IL-1β is the most important inducer of catabolic processes in OA. TNF-α, IL-6 and LIF also contribute to tissue erosion in advanced stages of OA, although their implication in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) prevails [31]. IL-1β activated primary chondrocytes express catabolic factors that degrade the ECM. OA chondrocytes were rather refractory to the patho-physiological trigger [7,32]. Here, we show that RHP and GLGPG impaired IL-1 expression in macrophages, leukocytes and chondrocytes. LIF, which is also involved in OA [14,28,29], was reduced by RHP and GLGPG. The data suggest that the substances exert their effects at an early phase of OA development and target different cell populations. Admittedly, this hypothesis needs to be tested in appropriate preclinical models.

While IL-6 is of key importance in RA, it is also involved in OA [33-36]. RHP inhibited IL-6 gene expression in chondrocytes, whereas its impact on cytokine production in macrophages or leukocytes was marginal. Thus, the effect of compounds was confined to cells, where excessive IL-6 production was deleterious; conversely, IL-6 was not modulated in peripheral blood leukocytes where it is required for an efficient humoral immune response. Similarly, TNF-α has multiple actions in the pathogenesis of RA [31] and may be a contributing factor to OA [1]. The tested natural substances reduced its expression in macrophages and leukocytes, while in chondrosarcoma cells the opposite effect on gene expression was observed. The meaning of this dichotomy is unclear and requires further investigation. Collectively, changes in IL-6 and TNF-α expression by RHP and GLGPG could influence the etiology of OA and RA. Indeed, in a recent clinical study, dietary supplementation of RA patients with RHP alleviated RA symptoms [37]. Obvious limitations in the interpretation of the current in vitro results should be noted: (1) the absence of data on bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of the substances makes it difficult to correlate the described in vitro effects with in vivo efficacy, (2) additional clinical trial to assess efficacy (anti-inflammatory versus pain-relief) of the test substances are warranted, (3) a possible effect of RHP and GLGPG on joint space widening should be investigated.

The involvement of NO and PGE2 in OA has been described in numerous studies [11,38-43]. The enhanced production of NO in OA joints contributed to a slowly progressing inflammation [9]. IL-1β treatment of chondrocytes induced iNOS and concomitant expression of cartilage-degrading enzymes [41,42,44-46]. Conversely, the progression of murine OA was slowed down in iNOS knock-out mice [47]. NO also activated MMPs [40] and PGE2 production [48] with concomitant inhibition of proteoglycan and collagen synthesis [43,49]. Chondrocyte apoptosis was promoted by NO and PGE2 [8,50-52]. In view of the observation that RHP and GLGPG diminished NO and PGE2 production, they might have anti-apoptotic effects in chondrocytes. The consequence of this inhibition is pivotal, since it affects (1) survival of chondrocytes, (2) production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and (3) activation of ECM-degrading enzymes. At the molecular level, the expression of prostaglandin E2 synthase (i.e. mPGES) [53-57] rather than COX-2 was altered by RHP (Table 2) and therefore only weakened the production of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins.

MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-13, ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 are key catabolic enzymes that degrade collagen and proteoglycan; their sequential expression might occur at, and herald different phases in the progression of OA [28,32,58]. Increased expression of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP) is associated with remodelling of articular tissues [59]. IL-1β induced a high MMP-1 expression in primary chondrocytes, which reflects events related to early OA; SW1353 displayed a pattern of MMP expression that relates to intermediate stages of OA. RHP and GLGPG exerted effects only on a sub-set of these enzymes: MMP-1, -3 and -13 and ADAMTS-4. Other members of the MMP family that have a role in tissue remodeling (e.g. MMP-9) [60] were not influenced by these treatments.

The impact of chemokines in OA has been substantiated previously [61]: CCL5/RANTES and CXCL8/IL-8 were identified in activated chondrocytes or OA tissue [14-16,62]. Expression levels of chemokines and their receptors dramatically change in IL-1β activated chondrocytes [7]. This emphasizes the putative role of chemokines in early and intermediate phases of progressing OA. Given the described effects of RHP and GLGPG, it is tempting to hypothesize that RHP components act as biological modifiers on chemotaxis in OA chondrocytes. In accordance with the in vitro study, clinical trials have provided evidence that chemotaxis of leukocytes is reduced after dietary supplementation with RHP [17].

Biological modulators such as IL-1β or NO eventually activate MAPK that, in turn, leads to the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus and NF-κB dependent gene activation. The kinetics and extent of RelA and NF-κB1 expression follow similar kinetics and amplitude in IL-1β stimulated SW1353, primary chondrocytes [28] and RAW264.7 cells (this study). In vitro studies have further demonstrated that this pathway was modulated by various substances contained in the food chain [63-68]. Regulatory motifs identified in chemokine genes include NF-κB [69]. Direct evidence that RHP and GLGPG may act along this pathway is provided by the observed down-regulation of NF-κB1, NF-κB49, NF-κBp65 and - as a consequence of decreased re-synthesis - I-κBα in activated macrophages (Table 2). The analysis of modification of these transcription factors like phosphorylation is required to substantiate this hypothesis. As previously shown [7,52,70,71], binding elements for other transcription factors (MEF-3, AP-1 and CEBPβ) have been mapped to the regulatory region of IL-1β- or LPS-responsive genes [7] and might also interact with RHP and GLGPG.

The in vitro effects described in this study were elicited at high concentrations of RHP and GLGPG. To date, no bioavailability studies have been reported for RHP; but it is unlikely that IC50 values for RHP and its constituent bioactive components are achieved in the body fluids or tissues as a consequence of dietary uptake. It is possible that after dietary intake RHP constituents accumulate in peripheral blood leukocytes and thus locally achieve threshold concentrations required for biological effects. Assuming that GLGPG is the only bioactive component in RHP powder, it can be deduced from the IC50 values given in Table 1 that RHP needs to contain ~3% of GLGPG. Yet, since the GLGPG contents of the studied RHP preparation does not exceed 0.1% of the dry plant mass (our unpublished results), we hypothesize that other substances contribute to the biological activity of RHP. The observation that substances contained in the food chain alter features of chondrocyte biology has been documented previously: polyphenols, including resveratrol and catechins (epigallocatechin-3-gallate, EGCG) reduced the expression of MMP-1, -3 or -13 and modulated levels of iNOS and COX-2 [63,65-68,72-74].

Conclusions

Both the onset and development of OA is expected to be modulated by the effects of RHP and GLGPG: (1) the observed diminished NO and IL-1β production is likely to delay or prevent initial steps of the disease, (2) the homeostasis of anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines is also modulated and thus provides a means to attenuate inflammatory processes in OA, and (3) chemokines that predominantly direct the migration of neutrophils were less abundantly produced (Table 7). RHP and its constituents thus modulate cellular and molecular processes that may explain the positive effect of RHP observed in clinical trials. The effects on interleukin and chemokine production as well as MMP expression indicate that RHP and its constituents down-regulate catabolic processes and reduce chemotaxis related to OA or RA. Collectively, the data provide a molecular and biochemical basis for the cartilage protection by RHP.

Table 7.

Synopsis of effects of RHP and GLGPG on cellular processes

| Type of mediators | Effect of RHP and GLGPG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In murine macrophages | In human PBL | In chondrocytes | Possible consequences of reduced expression or production | |

|

Chemokines (chemokine family) |

||||

| MIP-1α (CC) | Not significant | Reduced by GLGPG | -a | Recruitment of monocytes, T cells, B cells and eosinophils reduced by GLGPG |

| MIP-1β (CC) | -a | Reduced by GLGPG | -a | Recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils reduced by GLGPG |

| MIP-3α (CC) | -a | Reduced | Reduced | Recruitment of T lymphocytes reduced |

| CCL5/RANTES (CC) | Not significant | Reduced | Reduced | Recruitment of leukocytes diminished |

| MIP-2 (CXC) | -a | Not significant | Reduced by RHP | Recruitment of neutrophils diminished by RHP |

| IL-8 (CXC) | -a | Reduced | Reduced by RHP | Mainly reduced recruitment of neutrophils |

| CXCL10/IP-10 (CXC) | Reduced | Reduced | -a | Recruitment of activated T cells diminished |

| Interleukins/cytokines | ||||

| IL-10 | Increased | Increased | -a | Enhancement of anti-inflammatory processes |

| IL-1α | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced | Attenuation of inflammatory processes |

| IL-1β | Reduced | Not significant | Reduced | Attenuation of inflammatory processes |

| IL-6 | Unchanged | Unchanged | Reduced by RHP | Modulation of inflammatory processes in OA and RA |

| TNF-α | Reduced | Reduced | -a | Effects on initiation and progression of RA |

| Growth & differentiation factors | ||||

| G-CSF | Unchanged | Increased by RHP | Not significant | Modulation of immune response |

| GM-CSF | Unchanged | Increased by RHP | Not significant | Modulation of immune response |

| VEGF | -a | Increased by RHP | Not significant | Promotes angiogenesis |

| IFN-γ | Unchanged | Reduced | Not significant | Altered immune response |

a- = not measured

List of abbreviations

ADAMTS: a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type I motif; GLGPG: galactolipid (2S)-1: 2-di-O-[(9Z: 12Z: 15Z)-octadeca-9: 12: 15-trienoyl]-3-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl glycerol; IL: interleukin; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; NO: nitric oxide; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; OA: osteoarthritis; PBL: peripheral blood leukocytes; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; RHP: rose hip powder.

Competing interests

This research was funded by DSM Nutritional Products, where all authors are currently employed.

Authors' contributions

JS and NR conceived the experiments, NR performed the experiments, JS and NR analysed the experimental data, UH provided analytical data, JS and NR have written the paper, SW participated in drafting the study and revising the data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Effects of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7. RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS and cultured with 250 mg/L RHP or 9.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 4 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. Fold changes were calculated as specified in Materials and Methods.

Effects of RHP and GLGPG on cytokine/chemokine production in human peripheral blood leukocytes. LPS/IFN-γ -stimulated peripheral blood leukocytes were cultured with 250 mg/L RHP or 9.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 24 h and proteins were quantified by multi-parametric analysis as described in Materials and Methods.

Effects of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in human peripheral blood leukocytes. LPS/IFN-γ -stimulated cells were cultured with 250 mg/L RHP or 9.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 2 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR (for details see: Materials and Methods).

Contributor Information

Joseph Schwager, Email: Joseph.Schwager@dsm.com.

Ulrich Hoeller, Email: Ulrich.Hoeller@dsm.com.

Swen Wolfram, Email: Swen.Wolfram@dsm.com.

Nathalie Richard, Email: Nathalie.Richard@dsm.com.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Claus Kilpert (DSM Nutritional Products) and Grit Kluge (AnalytiCon Discovery, Berlin) for providing GLGPG and Lori Stern and James Edwards for carefully reading the article.

References

- Martel-Pelletier J, Boileau C, Pelletier JP, Roughley PJ. Cartilage in normal and osteoarthritis conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(2):351–384. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosang AJ, Little CB. Drug insight: aggrecanases as therapeutic targets for osteoarthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4(8):420–427. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q, Mort JS, Roughley PJ. Preferential mRNA expression of prostromelysin relative to procollagenase and in situ localization in human articular cartilage. J Clin Invest. 1992;89(4):1189–1197. doi: 10.1172/JCI115702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboul P, Pelletier JP, Tardif G, Cloutier JM, Martel-Pelletier J. The new collagenase, collagenase-3, is expressed and synthesized by human chondrocytes but not by synoviocytes. A role in osteoarthritis. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(9):2011–2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI118636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PG, Magna HA, Reeves LM, Lopresti-Morrow LL, Yocum SA, Rosner PJ, Geoghegan KF, Hambor JE. Cloning, expression, and type II collagenolytic activity of matrix metalloproteinase-13 from human osteoarthritic cartilage. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(3):761–768. doi: 10.1172/JCI118475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring SR, Goldring MB. The role of cytokines in cartilage matrix degeneration in osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004. pp. S27–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sandell LJ, Xing X, Franz C, Davies S, Chang LW, Patra D. Exuberant expression of chemokine genes by adult human articular chondrocytes in response to IL-1beta. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(12):1560–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring MB, Berenbaum F. The regulation of chondrocyte function by proinflammatory mediators: prostaglandins and nitric oxide. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004. pp. S37–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vuolteenaho K, Moilanen T, Knowles RG, Moilanen E. The role of nitric oxide in osteoarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36(4):247–258. doi: 10.1080/03009740701483014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy RM, Gomez PF, Abramson SB. Nitric oxide sustains nuclear factor kappaB activation in cytokine-stimulated chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(7):552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy RM, Abramson SB, Kohne C, Rediske J. Nitric oxide attenuates cellular hexose monophosphate shunt response to oxidants in articular chondrocytes and acts to promote oxidant injury. J Cell Physiol. 1997;172(2):183–191. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199708)172:2<183::AID-JCP5>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attur MG, Dave MN, Clancy RM, Patel IR, Abramson SB, Amin AR. Functional genomic analysis in arthritis-affected cartilage: yin-yang regulation of inflammatory mediators by alpha 5 beta 1 and alpha V beta 3 integrins. J Immunol. 2000;164(5):2684–2691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson SB, Attur M, Amin AR, Clancy R. Nitric oxide and inflammatory mediators in the perpetuation of osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3(6):535–541. doi: 10.1007/s11926-001-0069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaaeddine N, Di Battista JA, Pelletier JP, Kiansa K, Cloutier JM, Martel-Pelletier J. Differential effects of IL-8, LIF (pro-inflammatory) and IL-11 (anti-inflammatory) on TNF-alpha-induced PGE(2)release and on signalling pathways in human OA synovial fibroblasts. Cytokine. 1999;11(12):1020–1030. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaaeddine N, Olee T, Hashimoto S, Creighton-Achermann L, Lotz M. Production of the chemokine RANTES by articular chondrocytes and role in cartilage degradation. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(7):1633–1643. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1633::AID-ART286>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulai JI, Chen H, Im HJ, Kumar S, Hanning C, Hegde PS, Loeser RF. NF-kappa B mediates the stimulation of cytokine and chemokine expression by human articular chondrocytes in response to fibronectin fragments. J Immunol. 2005;174(9):5781–5788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazmi A, Winther K. Rose hip inhibits chemotaxis and chemiluminescence of human peripheral blood neutrophils in vitro and reduces certain inflammatory parameters in vivo. Inflammopharmacology. 1999;7(4):377–386. doi: 10.1007/s10787-999-0031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen E, Kharazmi A, Christensen LP, Christensen SB. An antiinflammatory galactolipid from rose hip (Rosa canina) that inhibits chemotaxis of human peripheral blood neutrophils in vitro. J Nat Prod. 2003;66(7):994–995. doi: 10.1021/np0300636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther K, Apel K, Thamsborg G. A powder made from seeds and shells of a rose-hip subspecies (Rosa canina) reduces symptoms of knee and hip osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34(4):302–308. doi: 10.1080/03009740510018624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrubasik JE, Roufogalis BD, Chrubasik S. Evidence of effectiveness of herbal antiinflammatory drugs in the treatment of painful osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain. Phytother Res. 2007;21(7):675–683. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrubasik C, Roufogalis BD, Muller-Ladner U, Chrubasik S. A systematic review on the Rosa canina effect and efficacy profiles. Phytother Res. 2008;22(6):725–733. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager AK, Eldeen IM, van Staden J. COX-1 and -2 activity of rose hip. Phytother Res. 2007;21(12):1251–1252. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager AK, Petersen KN, Thomasen G, Christensen SB. Isolation of linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids as COX-1 and -2 inhibitors in rose hip. Phytother Res. 2008;22(7):982–984. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WD, Mulvaney BD, Saathoff DJ. Leukocyte isolation by sedimentation: the effect of rouleau-promoting agents on leukocyte differential count. Prep Biochem. 1975;5(2):179–187. doi: 10.1080/00327487508061569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard N, Porath D, Radspieler A, Schwager J. Effects of resveratrol, piceatannol, tri-acetoxystilbene, and genistein on the inflammatory response of human peripheral blood leukocytes. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49(5):431–442. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200400099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Acquisto F, Cicatiello L, Iuvone T, Ialenti A, Ianaro A, Esumi H, Weisz A, Carnuccio R. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression by glucocorticoid-induced protein(s) in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated J774 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;339(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero M, Riera H, Colantuoni G, Khatib AM, Attalah H, Moldovan F, Mitrovic DR, Lomri A. Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor is anabolic and interleukin-1beta is catabolic for rat articular chondrocytes. Cytokine. 2008;44(3):366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer M, Saas J, Sohler F, Haag J, Soder S, Pieper M, Bartnik E, Beninga J, Zimmer R, Aigner T. Comparison of the chondrosarcoma cell line SW1353 with primary human adult articular chondrocytes with regard to their gene expression profile and reactivity to IL-1beta. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(8):697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz M, Moats T, Villiger PM. Leukemia inhibitory factor is expressed in cartilage and synovium and can contribute to the pathogenesis of arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1992;90(3):888–896. doi: 10.1172/JCI115964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struglics A, Larsson S, Pratta MA, Kumar S, Lark MW, Lohmander LS. Human osteoarthritis synovial fluid and joint cartilage contain both aggrecanase- and matrix metalloproteinase-generated aggrecan fragments. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(2):101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FM, McInnes IB. Evidence that cytokines play a role in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3537–3545. doi: 10.1172/JCI36389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aigner T, Zien A, Gehrsitz A, Gebhard PM, McKenna L. Anabolic and catabolic gene expression pattern analysis in normal versus osteoarthritic cartilage using complementary DNA-array technology. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(12):2777–2789. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2777::AID-ART465>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Marotte H, Kwan K, Ruth JH, Campbell PL, Rabquer BJ, Pakozdi A, Koch AE. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits IL-6 synthesis and suppresses transsignaling by enhancing soluble gp130 production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(38):14692–14697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802675105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca JE, Santos MJ, Canhao H, Choy E. Interleukin-6 as a key player in systemic inflammation and joint destruction. Autoimmun Rev. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jikko A, Wakisaka T, Iwamoto M, Hiranuma H, Kato Y, Maeda T, Fujishita M, Fuchihata H. Effects of interleukin-6 on proliferation and proteoglycan metabolism in articular chondrocyte cultures. Cell Biol Int. 1998;22(9-10):615–621. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1998.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz DC, Heller KD, Miltner O, Zilkens KW, Wolff JM. Interleukin-6: a potential inflammatory marker after total joint replacement. Int Orthop. 2000;24(4):194–196. doi: 10.1007/s002640000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willich SN, Rossnagel K, Roll S, Wagner A, Mune O, Erlendson J, Kharazmi A, Sorensen H, Winther K. Rose hip herbal remedy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis - a randomised controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin AR, Attur M, Patel RN, Thakker GD, Marshall PJ, Rediske J, Stuchin SA, Patel IR, Abramson SB. Superinduction of cyclooxygenase-2 activity in human osteoarthritis-affected cartilage. Influence of nitric oxide. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(6):1231–1237. doi: 10.1172/JCI119280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin AR, Di Cesare PE, Vyas P, Attur M, Tzeng E, Billiar TR, Stuchin SA, Abramson SB. The expression and regulation of nitric oxide synthase in human osteoarthritis-affected chondrocytes: evidence for up-regulated neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1995;182(6):2097–2102. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell GA, Jang D, Williams RJ. Nitric oxide activates metalloprotease enzymes in articular cartilage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206(1):15–21. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RM, Hickery MS, Charles IG, Moncada S, Bayliss MT. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in human chondrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193(1):398–405. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H, Kohsaka H, Liu MF, Higashiyama H, Hirata Y, Kanno K, Saito I, Miyasaka N. Nitric oxide production and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in inflammatory arthritides. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2357–2363. doi: 10.1172/JCI118292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskiran D, Stefanovic-Racic M, Georgescu H, Evans C. Nitric oxide mediates suppression of cartilage proteoglycan synthesis by interleukin-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200(1):142–148. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes IB, Leung BP, Field M, Wei XQ, Huang FP, Sturrock RD, Kinninmonth A, Weidner J, Mumford R, Liew FY. Production of nitric oxide in the synovial membrane of rheumatoid and osteoarthritis patients. J Exp Med. 1996;184(4):1519–1524. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski PS, Wright PK, Van 't Hof RJ, Helfrich MH, Ohshima H, Ralston SH. Immunolocalization of inducible nitric oxide synthase in synovium and cartilage in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(6):651–655. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchiorri C, Meliconi R, Frizziero L, Silvestri T, Pulsatelli L, Mazzetti I, Borzi RM, Uguccioni M, Facchini A. Enhanced and coordinated in vivo expression of inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide synthase by chondrocytes from patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(12):2165–2174. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2165::AID-ART11>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Loo FA, Arntz OJ, van Enckevort FH, van Lent PL, van den Berg WB. Reduced cartilage proteoglycan loss during zymosan-induced gonarthritis in NOS2-deficient mice and in anti-interleukin-1-treated wild-type mice with unabated joint inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(4):634–646. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199804)41:4<634::AID-ART10>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mello SB, Novaes GS, Laurindo IM, Muscara MN, Maciel FM, Cossermelli W. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitor influences prostaglandin and interleukin-1 production in experimental arthritic joints. Inflamm Res. 1997;46(2):72–77. doi: 10.1007/s000110050086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauselmann HJ, Oppliger L, Michel BA, Stefanovic-Racic M, Evans CH. Nitric oxide and proteoglycan biosynthesis by human articular chondrocytes in alginate culture. FEBS Lett. 1994;352(3):361–364. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00994-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notoya K, Jovanovic DV, Reboul P, Martel-Pelletier J, Mineau F, Pelletier JP. The induction of cell death in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes by nitric oxide is related to the production of prostaglandin E2 via the induction of cyclooxygenase-2. J Immunol. 2000;165(6):3402–3410. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic DV, Mineau F, Notoya K, Reboul P, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP. Nitric oxide induced cell death in human osteoarthritic synoviocytes is mediated by tyrosine kinase activation and hydrogen peroxide and/or superoxide formation. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(10):2165–2175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Ju JW, Oh CD, Yoon YM, Song WK, Kim JH, Yoo YJ, Bang OS, Kang SS, Chun JS. ERK-1/2 and p38 kinase oppositely regulate nitric oxide-induced apoptosis of chondrocytes in association with p53, caspase-3, and differentiation status. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(2):1332–1339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima F, Naraba H, Miyamoto S, Beppu M, Aoki H, Kawai S. Membrane-associated prostaglandin E synthase-1 is upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines in chondrocytes from patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(4):R355–365. doi: 10.1186/ar1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuko-Hongo K, Berenbaum F, Humbert L, Salvat C, Goldring MB, Thirion S. Up-regulation of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 in osteoarthritic human cartilage: critical roles of the ERK-1/2 and p38 signaling pathways. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9):2829–2838. doi: 10.1002/art.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Afif H, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Li X, Farrajota K, Lavigne M, Fahmi H. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 expression in human synovial fibroblasts by interfering with Egr-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(21):22057–22065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Afif H, Cheng S, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Ranger P, Fahmi H. Expression and regulation of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 in human osteoarthritic cartilage and chondrocytes. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(5):887–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrajota K, Cheng S, Martel-Pelletier J, Afif H, Pelletier JP, Li X, Ranger P, Fahmi H. Inhibition of interleukin-1beta-induced cyclooxygenase 2 expression in human synovial fibroblasts by 15-deoxy-Delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2 through a histone deacetylase-independent mechanism. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):94–104. doi: 10.1002/art.20714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bau B, Gebhard PM, Haag J, Knorr T, Bartnik E, Aigner T. Relative messenger RNA expression profiling of collagenases and aggrecanases in human articular chondrocytes in vivo and in vitro. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(10):2648–2657. doi: 10.1002/art.10531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Grover J, Roughley PJ, DiBattista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Zafarullah M. Expression of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) gene family in normal and osteoarthritic joints. Rheumatol Int. 1999;18(5-6):183–191. doi: 10.1007/s002960050083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow AK, Cena J, Schulz R. Acute actions and novel targets of matrix metalloproteinases in the heart and vasculature. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152(2):189–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan GH, Masuko-Hongo K, Sakata M, Tsuruha J, Onuma H, Nakamura H, Aoki H, Kato T, Nishioka K. The role of C-C chemokines and their receptors in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(5):1056–1070. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1056::AID-ANR186>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil DL, Johnson K, Rediske J, Lotz M, Schmidt AM, Terkeltaub R. Inflammation-induced chondrocyte hypertrophy is driven by receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Immunol. 2005;175(12):8296–8302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Wang N, Lalonde M, Goldberg VM, Haqqi TM. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) differentially inhibits interleukin-1 beta-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -13 in human chondrocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308(2):767–773. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaki C, Keshishzadeh N, Fischer K, Shakibaei M. Regulation of inflammation signalling by resveratrol in human chondrocytes in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(3):677–687. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakibaei M, Csaki C, Nebrich S, Mobasheri A. Resveratrol suppresses interleukin-1beta-induced inflammatory signaling and apoptosis in human articular chondrocytes: potential for use as a novel nutraceutical for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76(11):1426–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakibaei M, John T, Seifarth C, Mobasheri A. Resveratrol inhibits IL-1 beta-induced stimulation of caspase-3 and cleavage of PARP in human articular chondrocytes in vitro. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1095:554–563. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Ahmed S, Islam N, Goldberg VM, Haqqi TM. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase and production of nitric oxide in human chondrocytes: suppression of nuclear factor kappaB activation by degradation of the inhibitor of nuclear factor kappaB. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(8):2079–2086. doi: 10.1002/art.10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester J, Liacini A, Li WQ, Dehnade F, Zafarullah M. Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F extract suppresses proinflammatory cytokine-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase genes in articular chondrocytes by inhibiting activating protein-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB activities. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59(5):1196–1205. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SR, Chang LW, Patra D, Xing X, Posey K, Hecht J, Stormo GD, Sandell LJ. Computational identification and functional validation of regulatory motifs in cartilage-expressed genes. Genome Res. 2007;17(10):1438–1447. doi: 10.1101/gr.6224007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K, Li J, Yu H, Fukui N, Sandell LJ. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins beta and delta mediate the repression of gene transcription of cartilage-derived retinoic acid-sensitive protein induced by interleukin-1 beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(35):31526–31533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin P, Algarte M, Roof P, Lin R, Hiscott J. Regulation of RANTES chemokine gene expression requires cooperativity between NF-kappa B and IFN-regulatory factor transcription factors. J Immunol. 2000;164(10):5352–5361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Rahman A, Hasnain A, Lalonde M, Goldberg VM, Haqqi TM. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the IL-1 beta-induced activity and expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase-2 in human chondrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33(8):1097–1105. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liacini A, Sylvester J, Zafarullah M. Triptolide suppresses proinflammatory cytokine-induced matrix metalloproteinase and aggrecanase-1 gene expression in chondrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327(1):320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrotin YE, Sanchez C, Deberg MA, Piccardi N, Guillou GB, Msika P, Reginster JY. Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables increase aggrecan synthesis and reduce catabolic and proinflammatory mediator production by human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(8):1825–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7. RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS and cultured with 250 mg/L RHP or 9.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 4 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. Fold changes were calculated as specified in Materials and Methods.

Effects of RHP and GLGPG on cytokine/chemokine production in human peripheral blood leukocytes. LPS/IFN-γ -stimulated peripheral blood leukocytes were cultured with 250 mg/L RHP or 9.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 24 h and proteins were quantified by multi-parametric analysis as described in Materials and Methods.

Effects of RHP and GLGPG on gene expression in human peripheral blood leukocytes. LPS/IFN-γ -stimulated cells were cultured with 250 mg/L RHP or 9.7 mg/L of GLGPG for 2 h and gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR (for details see: Materials and Methods).