Abstract

FTIR spectroscopy is sensitive to the molecular composition of tissue and has the potential to identify pre-malignant tissue (dysplasia) as an adjunct to endoscopy. We demonstrate collection of mid-infrared absorption spectra with a silver halide (AgCl0.4Br0.6) optical fiber and use spectral pre-processing to identify optimal sub-ranges that classify colonic mucosa as normal, hyperplasia, or dysplasia. We collected spectra (n = 83) in the 950 to 1800 cm−1 regime on biopsy specimens obtained from human subjects (n = 37). Subtle differences in the magnitude of the absorbance peaks at specific wavenumbers were observed. The best double binary algorithm for distinguishing normal-versus-dysplasia and hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia was determined from an exhaustive search of spectral intervals and pre-processing techniques. Partial least squares discriminant analysis was used to classify the spectra using a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation strategy. The results were compared with histology reviewed independently by two gastrointestinal pathologists. The optimal thresholds identified resulted in an overall sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and positive predictive value of 96%, 92%, 93%, and 82%, respectively. These results indicated that mid-infrared absorption spectra collected remotely with an optical fiber can be used to identify colonic dysplasia with high accuracy, suggesting that continued development of this technique for the early detection of cancer is promising.

Keywords: FTIR, dysplasia, optical fiber, early detection, cancer, endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third most common form of malignancy in the United States, and approximately 149,900 new cases and 50,000 deaths occur each year, resulting in a major cause of morbidity and mortality.1 Screening for this disease is commonly done with endoscopy, in which the mucosal surface of the colon is examined with reflected white light, to look for raised lesions called polyps. Such polyps can be either benign (hyperplastic) or pre-malignant (dysplastic, termed adenomas), but definitive pathological diagnosis cannot be made unless a biopsy is performed. Hyperplastic polyps have no risk of evolving into malignancy, while dysplastic lesions have a predictable risk that increases with the size of the lesion.2 Dysplastic mucosa can persist in a latent phase for approximately 10 to 20 years before transforming, thus a window of opportunity exists to prevent cancer if adequate techniques for early detection can be developed. In addition, numerous benign inflammatory polyps can be found in patients with inflammatory bowel disease that cannot be distinguished endoscopically from dysplastic polyps.3 Polyp removal during endoscopy incurs an increased risk of bleeding or perforation. In addition, it takes time to excise these lesions, thus prolonging the duration of sedation, and additional cost is incurred for histopathological examination of tissue. Thus, a technique that can identify dysplasia during endoscopy could have tremendous diagnostic value in medical care.

The absorption of infrared light by the inter-atomic bonds in tissue macromolecules can be measured by techniques of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. This method has demonstrated promise for detection of cancer in a number of tissues including skin,4 cervix,5–8 esophagus,9,10 stomach,11,12 lung,13 ovary,14 prostate,15 and colon.16–19 FTIR spectra can reveal the molecular composition of the tissues without use of exogenous contrast agents.20,21 Instead, a number of endogenous biomolecules can provide a characteristic spectrum of infrared absorption peaks constituting a molecular “fingerprint”, revealing the biochemical composition of the tissue. The use of FTIR to detect the presence and to measure the concentration of these specific molecules can provide important diagnostic information. Previously, we have measured FTIR spectra with attenuated total reflectance (ATR) by placing the tissue specimen in contact with a zinc selenide (ZnSe) crystal.10 In this mode, the infrared beam reflects at the interface between the crystal and the tissue below the critical angle and undergoes total internal reflection generating an evanescent wave with a depth of 2 to 3 microns into the tissue. This was used to determine the relative concentrations of the key endogenous biomolecules.

Recently, flexible optical fibers have been developed with polycrystalline silver halide materials for collecting FTIR spectra which may be configured to be endoscope compatible and can enable interrogation of the molecular composition of tissues during endoscopic procedures.22–31 Fibers that transmit infrared light can be made with a variety of materials; however, silver halides, such as AgCl0.4Br0.6, have advantages for in vivo applications that include broad spectral transmission, good mechanical flexibility, low optical attenuation, long term stability, non-hygroscopicity, and non-toxicity.24,26,28 Silver halide transmits infrared radiation from 400 to 25,000 cm−1, depending on the fiber composition, with low attenuation (0.5 dB/m at 10.6 μm),24 and can be fabricated into optical fibers that are several meters in length. Here, we demonstrate the use of an endoscope compatible silver halide optical fiber to collect FTIR spectra from freshly excised specimens of colonic mucosa, including normal, hyperplastic, and dysplastic mucosa. Because dysplasia is one of the early steps in the transformation process toward cancer, the molecular changes at this stage are expected to have subtle spectral differences compared to that of normal colonic mucosa and hyperplasia. Thus, we will need sophisticated spectral processing algorithms to accurately classify these specimens. The mid-infrared (MIR) spectral range (2–20 μm) is evaluated because this regime contains numerous absorption maxima of fundamental rotational and vibrational modes of biochemical bonds.22

METHODS

Recruitment and Specimen Processing

A total of 37 subjects undergoing routine screening colonoscopy with a mean age of 62 years (range 26 to 84 years) were recruited for this study. The protocol was approved by the human subjects committee (IRB) at Stanford University and the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS). After informed consent, routine screening was performed using a standard video colonoscope in the Endoscopy Unit at the VAPAHCS hospital. When a polyp was identified, a pinch biopsy with jumbo forceps was taken from the lesion and an adjacent site of normal appearing mucosa. The endoscopic appearance and anatomic location of each lesion biopsied was recorded. Immediately after resection, half of the biopsy specimen was placed on moist gauze over ice in a container for transport to the FTIR spectrometer. The other half of each specimen was sent for routine histopathological evaluation. Water was removed from the mucosal surface of each specimen by blowing cool air for ~5 minutes. FTIR spectra were then obtained, as described below. Following the collection of spectra, each piece of tissue was then rehydrated with normal saline (0.9%) and placed in 10% buffered formalin. The tissues were processed and cut in 4 μm sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and analyzed by two gastrointestinal pathologists (MRA, JMC). Only specimens that were consistent with the endoscopic findings (polypoid versus normal appearing) were included in the analysis. This resulted in n = 83 spectra from n = 33 of the original 37 subjects, including n = 42, 17, and 24 specimens of normal, hyperplasia, and dysplasia, respectively.

FTIR Spectra Collection from Colon Specimens

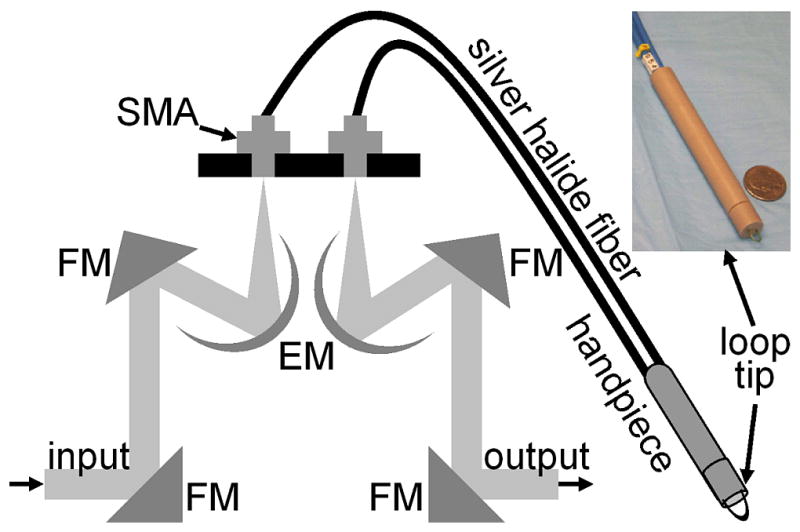

A FTIR spectrometer (Nexus 470, Thermo Electron, Madison, WI) was used to measure the spectra and was continuously purged with air to remove water vapor and CO2. A Multi-Loop-MIRTM silver halide optical fiber (Harrick Scientific, Pleasantville, NY) is coupled to a FiberMateTM module via SMA connectors. This module contains a set of elliptical (EM) and flat mirrors (FM), as shown in Fig. 1, that define the optical path, and is inserted into the signal arm of the Michelson interferometer used by the spectrometer. The input and output fibers are each one meter long and have a diameter of 900 μm. The distal end of the fibers terminates into a handpiece that has an overall diameter of 10 mm with a 6.4 diameter replaceable fiber tip. The diameter of the handpiece is determined by the minimum bend radius of the silver halide fiber. In the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) configuration, the fiber tip is formed into a loop so that there is no physical interruption of the light path between the light delivery (input) and collection (output) fibers. The specimen is placed on a linear translational stage, which is adjusted until the distal tip of the fiber is in contact for spectral collection. A mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector cooled with liquid nitrogen and set at an autogain of 4 was used to record the spectra with a resolution of 4 cm−1 using 36 co-added scans for both the background and tissue. The extent of hydration was determined using a ratio between the Amide I and Amide II bands at 1650 and 1545 cm−1, respectively. This process was used to adjust the drying time to provide a consistent peak at 1640 cm−1.

Figure 1.

The optical fiber is coupled to the spectrometer via SMA connectors, and the optical path is defined by a set of elliptical (EM) and flat mirrors (FM). The input and output arms of the fiber are one meter long each with a diameter of 900 μm, and the distal end terminates into a handpiece that has a diameter of 10 mm and attaches to a replaceable 6.4 mm loop tip. The photo shows the handpiece next to a quarter for size comparison.

Spectral Analysis

The FTIR spectra were evaluated using partial least squares (PLS) discriminant analysis,32–34, and the algorithms were implemented using the SIMPLS algorithm in the PLS_Toolbox, a commercially available software package (Eigenvector Research, Inc., Wenatchee, WA).35 The spectra were first pre-processed to remove variance that is not relevant for predicting class membership. The simplest pre-processing method is interval PLS, where a subset of wavelengths (wavenumbers) are identified that provides a superior predictive value in comparison to use of all the wavelengths collected.35 Interval PLS discriminant analysis is performed by conducting an exhaustive search for the best combination of wavelengths. In this study, the fingerprint regime was divided into six sub-ranges, and all possible combinations of sub-ranges were tested.

The two other basic categories of pre-processing are sample-wise and variable-wise methods. Sample-wise methods act on each spectrum one at a time to remove unwanted variance. Sample-wise pre-processing methods evaluated in this analysis include along-spectrum derivation, baseline subtraction, and normalization. Derivation was performed by applying the Savitsky-Golay algorithm,36 where a second-order polynomial was fit to a window around each value of the spectrum, and the value was then replaced with the second-order coefficient of the polynomial. Multiple window widths were also tested. When the derivation was not applied, a baseline spectrum, calculated as a low-order polynomial fit to the end regions of each spectrum, was subtracted. The relative values of spectral measurements often have greater predictive value than that of the absolute measurements. In this case, normalization is useful, and helps all spectra to have an equal impact in the model. Three different types of metric were evaluated, with either the area under the curve of a spectrum, the vector length of a spectrum, or the maximum value of a spectrum undergoing normalization.

Variable-wise pre-processing methods act on each spectral wavelength independently, but require multiple samples for parameter estimation before they are implemented. The variable-wise pre-processing method tested in this study was unit-variance scaling. In this method, the value of a spectrum (or pre-processed spectrum as unit-variance scaling always occurs as the last pre-processing step) at each wavelength was centered by subtracting the mean value across all samples, and then was scaled to unit variance by dividing by the standard deviation. Each sub-range was independently normalized to have the same area under the curve. The normalized values were then scaled to unit-variance by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation at each wavelength. By normalizing and scaling to unit-variance, the mixture of units due to a combination of baseline-subtraction in some sub-ranges and second derivative preprocessing in others are eliminated.

Classification Algorithm Design

We sought to identify diagnostic information from the subtle differences observed in the mid-infrared absorbance spectra collected from colonic mucosa, including normal, hyperplasia, and dysplasia. We developed a double binary detection algorithm that consists of one model to discriminate hyperplasia from dysplasia and another to distinguish normal from dysplasia. These distinctions are clinically relevant to patients that are found to have a very large number of polyps (> 10), where time limitations become a factor for lesion removal. The hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia and normal-versus-dysplasia models use spectra from respective tissue specimens for training. The total number of PLS discriminant analysis models tested for each is determined by the number of unique pre-processing combinations and exceeded 105. The accuracy of each component of the double binary model is assessed using leave-one-subject-out cross-validation to provide prospective analysis. The 30 most accurate hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia and normal-versus-dysplasia models were then selected for each. All 900 combinations of these two models were then tested in the double binary algorithm, again using leave-one-subject-out where spectra from each subject are rotated out for cross-validation. After a completing the rotation, each spectrum has classification values for both hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia and normal-versus-dysplasia regardless of the true tissue class. Classification thresholds are varied in two-dimensions, and the double binary algorithm is scored using histopathology as the “gold standard.” The final algorithm reported consists of the best hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia and normal-versus-dysplasia combination in terms of sensitivity and specificity for dysplasia.

RESULTS

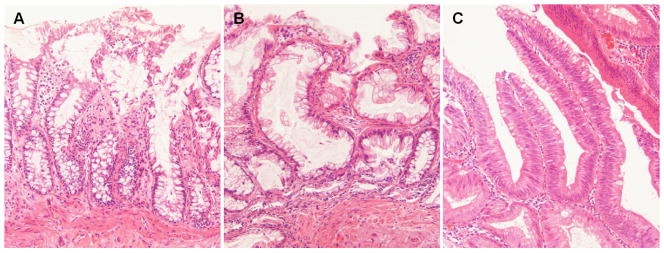

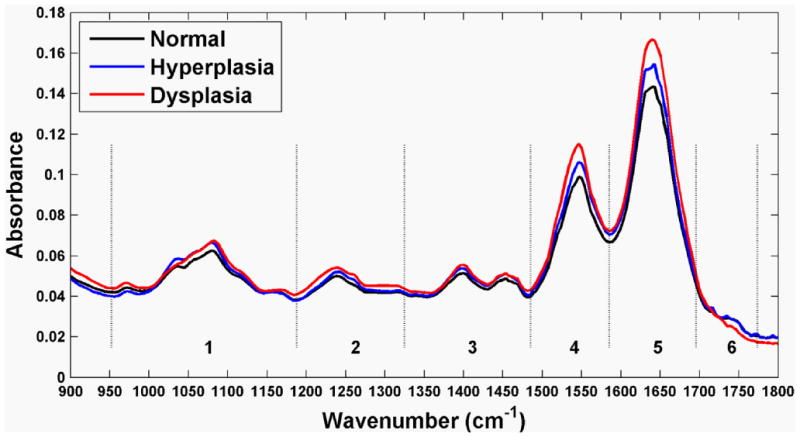

The average FTIR spectra collected with the silver halide optical fiber from specimens of colonic mucosa, including normal, hyperplasia, and dysplasia, are shown in Fig. 2. An average ratio of 0.687±0.009 (SEM) was found between the Amide I and Amide II peaks from the (n = 83) spectra and is used as an internal control. The spectra reveal subtle differences among the three histological classes in terms of location and height of the absorbance peaks. The spectra are divided into the optimal six sub-ranges found from the algorithm described in the Methods, and are indicated by the dashed vertical lines. These sub-ranges correspond to the groups of vibrational modes listed in Table 1 (spectral ranges 1 to 6). Representative histology (H&E) for the specimens of colonic mucosa studied are shown in Fig. 3. Although some dessication artifact was observed, it did not prevent reliable classification of the mucosal samples into normal, hyperplastic, or dysplastic categories. Because of the possibility that the two halves of each biopsy specimen might differ histologically, the results reported herein are based on interpretation of the half-specimen from which the FTIR spectra were obtained.

Figure 2.

The mean mid-infrared absorbance spectra from biopsy specimens of colonic mucosa, including normal (n = 42), hyperplasia (n = 17), and dysplasia (n = 24) collected with the silver halide optical fiber show subtle differences in average location and height of the absorbance peaks.

Table 1.

Primary mid-infrared absorption band assignments to tissue biomolecules in the 950 cm−1 to 1800 cm−1 spectral regime. The references cited are within 5 cm−1 of those found in this study.

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Biochemical | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range 1 | ||

| 966 | DNA | 17 |

| 996 | RNA | 17 |

| 1015 | DNA | 38 |

| 1026 | glycogen | 10 |

| 1056 | RNA, DNA, lipids | 38 |

| 1080 | glycogen | 16 |

| 1085 | phosphates (RNA, DNA, phospholipids) | 38 |

| 1121 | RNA | 17 |

| 1154 | glycogen | 38 |

| 1164 | glycoprotein | 10 |

| Spectral Range 2 | ||

| 1225 | phosphates (RNA, DNA, phospholipids) | 39 |

| 1240 | protein (Amide III) | 10 |

| 1241 | phosphates (RNA, DNA, phospholipids) | 18 |

| 1260 | protein (Amide III) | 39 |

| 1280 | protein (Amide III) | 39 |

| 1301 | protein (Amide III) | 10 |

| Spectral Range 3 | ||

| 1350 | lipids | 17 |

| 1370 | protein | 39 |

| 1398 | protein | 10 |

| 1400 | lipids | 13 |

| 1454 | protein | 10 |

| Spectral Range 4 | ||

| 1512 | protein | 17 |

| 1545 | protein (Amide II) | 17 |

| Spectral Range 5 | ||

| 1640 | water | 40 |

| 1650 | protein (Amide I) | 40 |

| Spectral Range 6 | ||

| 1740 | lipids | 40 |

Figure 3.

Histology of specimens examined after FTIR evaluation. A. normal – In contrast to mucosal specimens placed directly into formalin fixative, following FTIR evaluation there is some disruption of surface epithelial cells as a result of dessication. In most instances, this did not preclude diagnostic assessment on the specific mucosal samples examined by FTIR. B. hyperplasia – The characteristic serrated profile of crypt and surface epithelial cells is present. C. dysplasia – Both adenomatous crypt and villiform architecture are present. Original magnification, 200X.

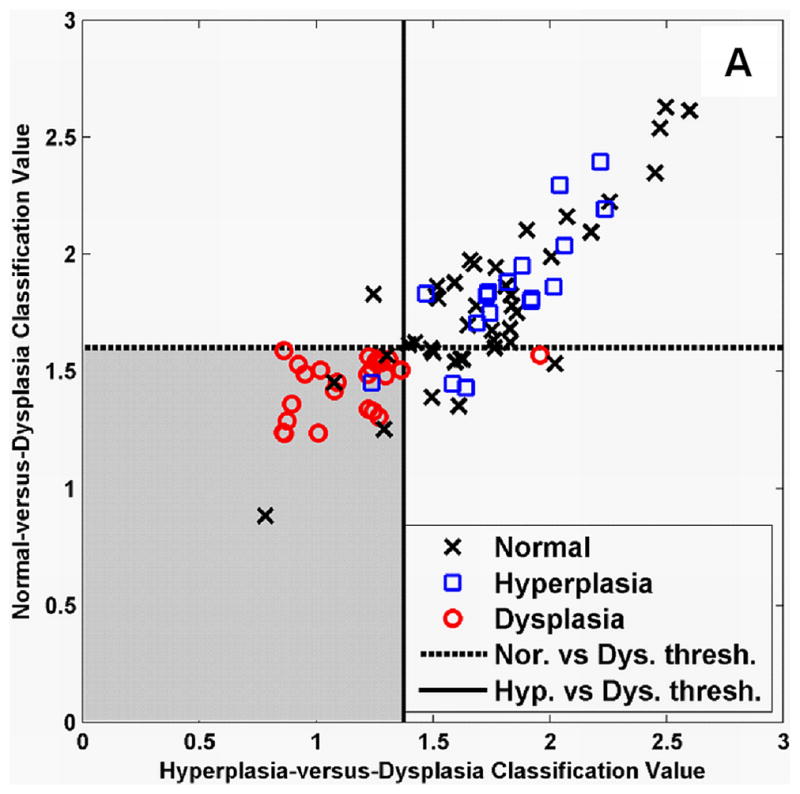

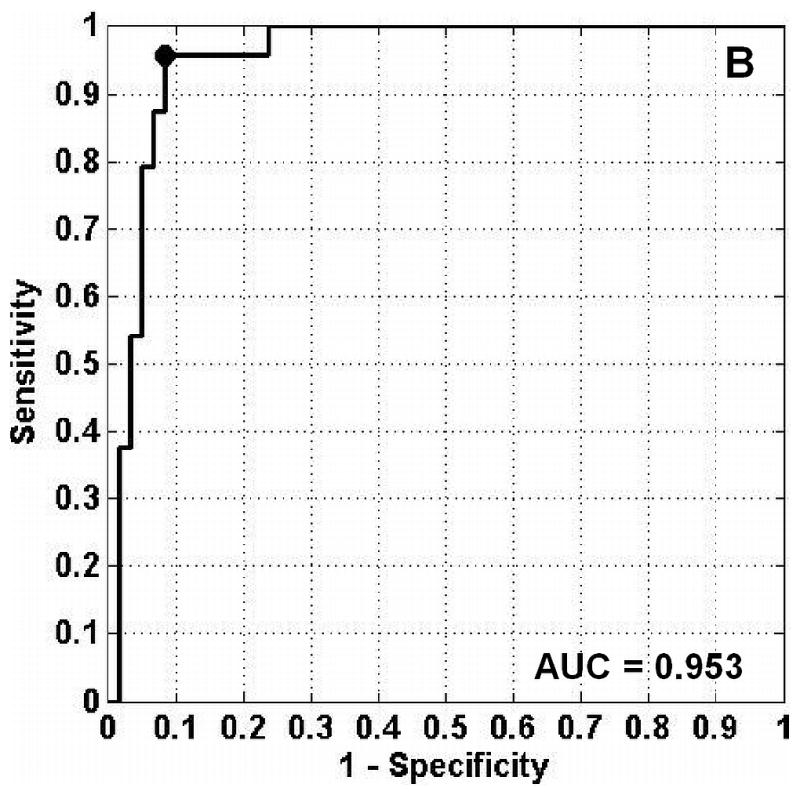

The classification of each specimen using the best double binary algorithm is shown in the scatter plot in Fig. 4A, with the optimal thresholds for distinguishing hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia and normal-versus-dysplasia indicated by the solid vertical and dashed horizontal lines, respectively. Dysplasia was classified with sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 92%, respectively, and the accuracy and positive predictive value was 93% and 82%, respectively. In Fig. 4A, the 4 data points for normal (black crosses) in the lower left hand corner represents a false positives on the dysplasia-versus-hyperplasia decision line, and the data point for dysplasia (red circle) in the lower right hand corner represents a false negative on the hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia decision line. The samples in the bottom right quadrant of Fig. 4A are classified as non-dysplasia by the hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia model. The specificity for the hyperplasia specimens alone was 93%. The receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve for the double binary algorithm applied to all samples is shown in Fig. 4B, and reveals an optimal tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 92%, respectively, for dysplasia and non-dysplasia, shown by the black dot in the upper left hand corner. The area under the curve was 0.953.

Figure 4.

Results of best two-part algorithm for classification of tissue. A. Scatter plot shows true positives for dysplasia as red circles in shaded area, true negatives for non-adenoma as black crosses (normal) and blue squares (hyperplasia) in the un-shaded area. Optimal thresholds for distinguishing hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia and normal-versus-dysplasia are indicated by the solid vertical and dashed horizontal lines, respectively. B. ROC curve for best two-part algorithm shows optimal tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 92% (black dot). The area under the curve is 0.953.

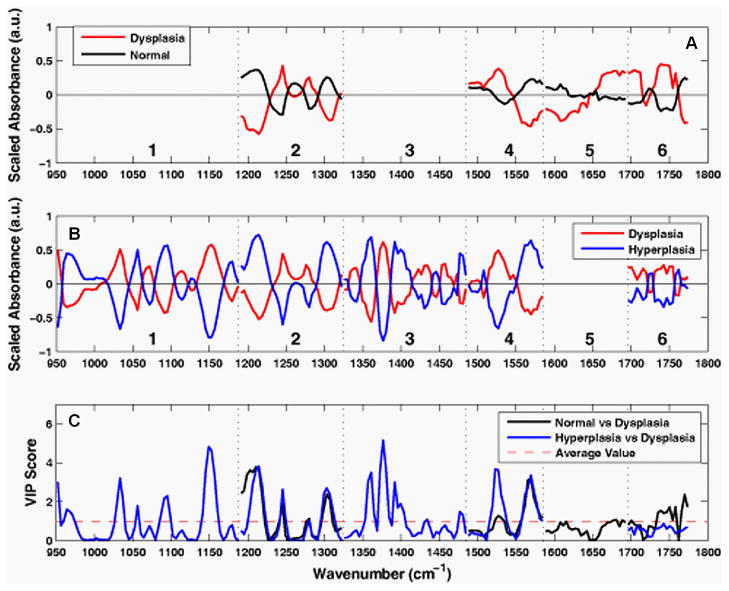

The spectral data after wavelength selection and pre-processing for input to the PLS discriminant analysis regression are shown by class average in Fig. 5A for the normal-versus-dysplasia model and in Fig. 5B for the hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia model. Note that the optimal model for normal-versus-dysplasia only included sub-range 5, where Amide I and water are the predominant contributors to the absorbance peaks. This model used sub-ranges 4 and 5 with baseline-removal only, while Savitzky-Golay second derivative pre-processing was applied to sub-ranges 2 and 6, respectively. The hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia model excluded sub-range 5 only. Sub-range 4 was used with baseline-removal, while the Savitzky-Golay second derivative pre-processing was applied to sub-ranges 1, 2, 3, and 6. The hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia model used the same normalization scheme as the normal-versus-dysplasia model, and was also scaled to unit-variance. The normal-versus-dysplasia and hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia models both employed only two latent variables, suggesting that the scaling process removes extraneous variance that would otherwise be captured by additional latent variables.

Figure 5.

Pre-processed spectra and variable importance for projection (VIP) curves. The mean pre-processed spectra for the A. normal-versus-dysplasia model and the B. hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia model are shown. The spectra are divided into six optimal sub-ranges as shown by the dashed vertical lines, and the peaks are assigned in Table 1. C. VIP scores for the normal-versus-dysplasia and hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia models reflect relative importance of each wavenumber to the model.

The variable importance for projection (VIP) curves for the normal-versus-dysplasia and hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia models are shown in Fig. 5C. This score summarizes the importance of each wavenumber for modeling both the variance of the predictors (spectra) and that of the response (classes).37 By definition, the average VIP score is one, and variables with values much greater than one are the most important for the model, while those with values much less than one make a negligible contribution. The VIP results show that the glycogen peaks for hyperplasia at 1026 and 1154 cm−1 (Table 1) in sub-range 1 are important for distinguishing them from dysplasia and that the Amide I and lipid peaks of sub-ranges 5 and 6 are relatively unimportant. While these spectral differences can be clearly discerned in the average spectra of Fig. 2, the differences in protein, lipid, and phosphate peaks of sub-ranges 2, 3, and 4 are much more subtle in the average spectra. However after pre-processing, these differences are amplified and these peaks are clearly valuable for classification.

DISCUSSION

Here, we demonstrate the use of an optical fiber to collect FTIR spectra remotely from freshly excised colonic mucosa, and found that adequate signal could be obtained with use of a silver halide fiber that is transparent in the mid-infrared regime, a sensitive liquid nitrogen cooled MCT detector, and an efficient FTIR spectrometer. While the fiber used in this study is not sufficiently long or thin enough to pass through a standard medical colonoscope, there are specialty instruments available, including therapeutic sigmoidoscopes, that have comparable lengths and channel diameters. The fiber is sealed within a protective jacket, and the exposed loop tip was replaced after several measurements to prevent degradation of signal. Because the specimens were studied immediately after excision, we expect that these results will be representative of that found in viable colonic mucosa. We observed subtle differences in the average location and magnitude of the absorbance peaks among normal, hyperplasia, and dysplasia in the fingerprint region between 950 and 1800 cm−1. Regression of these datasets is challenging because they are underdetermined and collinear. That is, there are more spectral peaks that exist than there are spectra in each class, and a high correlation occurs between absorbance maxima for unique biomolecules. Nonetheless, we were able to tease out these subtle spectral differences by performing an exhaustive search for the optimal sub-range intervals to be used in the PLS discriminant analysis with rigorous spectral pre-processing techniques. In the end, we were able to develop a double binary algorithm that could distinguish normal from dysplasia and hyperplasia from dysplasia with high sensitivity and specificity.

We are able to simplify this complex spectral dataset into a handful of latent variables that could then be evaluated by PLS discriminant analysis. The underlying assumption of this analysis is that the observations are generated by a process driven by a small number of latent (not directly observed) variables, and the data measured can be projected onto these latent variables by maximizing the covariance of predictor variables (spectral absorbances) and responses (class membership). The number of latent variables is limited to four in this study to avoid over-fitting the spectra. Residual water can be a serious interference with FTIR spectra. However, with attenuated total reflectance (ATR) we only need to remove water within the most superficial 2 to 3 micron layer of the tissue. This depth is much less than the dimension of a single cell, so the removal of water over this layer is feasible. As a consequence, we were able to address the spectral peak associated with water, a major source of absorbance in tissue. Our model for distinguishing hyperplasia from dysplasia could completely eliminate this effect by avoiding use of sub-range 5 (Fig. 5B). In addition, we can provide physiological explanation to interpret the spectral changes observed among the three classes of colonic mucosa with use of Table 1. Our spectra provides a unique “snapshot” of the biochemical composition of the mucosa at different steps along the cancer transformation process.20 The absorbance peak for RNA rises relative to that of DNA. Some of these spectral differences are apparent in Fig. 2, while others are not visually obvious. We also found that in addition to the well-known glycogen, nucleic acid, and amide protein peaks, there is useful diagnostic information in the lipids and weaker protein vibrations. In particular, it is notable that sub-ranges 1 (glycogen and nucleic acids) and 3 (proteins and lipids) are not included in the normal-versus-dysplasia model at all, while they are important components of the hyperplasia-versus-dysplasia model, suggesting that these biomolecules have an important role in cellular proliferation.

For future development of this technology, the use of a classification algorithm that minimizes the amount of information required for calibration transfer between the optical fiber instruments is desirable. With the use of unit-variance scaling, a mean and standard deviation at each wavelength must be included as part of the calibration transfer, in addition to the regression coefficients. However, unit-variance scaling was found to provide clearly better performance. If the additional burden upon calibration transfer presented by unit-variance scaling is not significant even in the production of large number of optical fiber instruments, then unit-variance scaling should be employed as a pre-processing component in the algorithm utilized by this technique.

CONCLUSIONS

These results demonstrate that collection and use of FTIR spectra with an endoscope-compatible optical fiber is feasible for distinguishing pre-malignant colonic mucosa, and that the relatively simple spectral biomarkers used to identify dysplasia can potentially be measured in vivo with continued development of this technology. These exciting findings suggest that continued development of an endoscope compatible instrument for collecting FTIR spectra to identify pre-malignant mucosa in the colon is feasible, and has implications for evaluating histopathology in situ as a novel approach for early detection of cancer in the colon that may be generalized to hollow organs.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including K08 DK67618, P50 CA93990, and U54 CA136429 (TDW) and the Department of Defense USAMRCMC W81XWH-05-C-0086 (RW) and by the Stanford Infrared Science and FEL Center as a grant from the United States Air Force Office of Sponsored Research (F9550-04-1-0075; CHC).

References

- 1.Cancer Facts & Figures 2008. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu C, Crawford JM. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, editors. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin DT, Rothe JA, Hetzel JT, Cohen RD, Hanauer SB. Are dysplasia colorectal cancer endoscopically visible in patients with ulcerative colitis? Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2007;65:998–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chew SF, Wood BR, Kanaan C, Browning J, MacGregor D, Davis ID, Cebon J, Tait BD, McNaughton D. Fourier transform infrared imaging as a method for detection of HLA class I expression in melanoma without the use of antibody. Tissue Antigens. 2007;69:252–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark S, Sahu RK, Kantarovich K, Podshyvalov A, Guterman H, Goldstein J, Jagannathan R, Argov S, Mordechai S. Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy as a quantitative diagnostic tool for assignment of premalignancy grading in cervical neoplasia. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2004;9:558–567. doi: 10.1117/1.1699041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podshyvalov A, Sahu RK, Mark S, Kantarovich K, Guterman H, Goldstein J, Jagannathan R, Argov S, Mordechai S. Distinction of cervical cancer biopsies by use of infrared microspectroscopy and probabilistic neural networks. Applied Optics. 2005;44:3725–3734. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.003725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romeo MJ, Wood BR, Quinn MA, McNaughton D. Removal of blood components from cervical smears: Implications for cancer diagnosis using FTIR spectroscopy. Biopolymers. 2003;72:69–76. doi: 10.1002/bip.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood BR, Quinn MA, Burden FR, McNaughton D. An investigation into FTIR spectroscopy as a biodiagnostic tool for cervical cancer. Biospectroscopy. 1996;2:143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang JS, Shi JS, Xu YZ, Duan XY, Zhang L, Wang J, Yang LM, Weng SF, Wu JG. FT-IR spectroscopic analysis of normal and cancerous tissues of esophagus. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;9:1897–1899. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i9.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang TD, Triadafilopoulos G, Crawford JM, Dixon LR, Bhandari T, Sahbaie P, Friediand S, Soetikno R, Contag CH. Detection of endogenous biomolecules in Barrett’s esophagus by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:15864–15869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707567104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujioka N, Morimoto Y, Arai T, Kikuchi M. Discrimination between normal and malignant human gastric tissues by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2004;28:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li QB, Sun XJ, Xu YZ, Yang LM, Zhang YF, Weng SF, Shi JS, Wu JG. Diagnosis of gastric inflammation and malignancy in endoscopic biopsies based on Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Clinical Chemistry. 2005;51:346–350. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.037986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yano K, Ohoshima S, Gotou Y, Kumaido K, Moriguchi T, Katayama H. Direct measurement of human lung cancerous and noncancerous tissues by Fourier transform infrared microscopy: Can an infrared microscope be used as a clinical tool? Analytical Biochemistry. 2000;287:218–225. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishna CM, Sockalingum GD, Bhat RA, Venteo L, Kushtagi P, Pluot M, Manfait M. FTIR and Raman microspectroscopy of normal, benign, and malignant formalin-fixed ovarian tissues. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2007;387:1649–1656. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gazi E, Dwyer J, Gardner P, Ghanbari-Siahkali A, Wade AP, Miyan J, Lockyer NP, Vickerman JC, Clarke NW, Shanks JH, Scott LJ, Hart CA, Brown M. Applications of Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy in studies of benign prostate and prostate cancer. A pilot study. Journal of Pathology. 2003;201:99–108. doi: 10.1002/path.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argov S, Ramesh J, Salman A, Sinelnikov I, Goldstein J, Guterman H, Mordechai S. Diagnostic potential of Fourier-transform infrared microspectroscopy and advanced computational methods in colon cancer patients. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2002;7:248–254. doi: 10.1117/1.1463051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Argov S, Sahu RK, Bernshtain E, Salman A, Shohat G, Zelig U, Mordechai S. Inflamatory bowel diseases as an intermediate stage between normal and cancer: A FTIR-microspectroscopy approach. Biopolymers. 2004;75:384–392. doi: 10.1002/bip.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigas B, Morgello S, Goldman IS, Wong PTT. Human Colorectal Cancers Display Abnormal Fourier-Transform Infrared-Spectra. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:8140–8144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi S, Satomi A, Yano K, Kawase H, Tanimizu T, Tuji Y, Murakami S, Hirayama R. Estimation of glycogen levels in human colorectal cancer tissue: relationship with cell cycle and tumor outgrowth. Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;34:474–480. doi: 10.1007/s005350050299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrus PGL, Strickland RD. Cancer grading by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biospectroscopy. 1998;4:37–46. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6343(1998)4:1<37::aid-bspy4>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahu RK, Argov S, Salman A, Zelig U, Huleihel M, Grossman N, Gopas J, Kapelushnik J, Mordechai S. Can Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy at higher wavenumbers (mid IR) shed light on biomarkers for carcinogenesis in tissues? Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2005;10:054017. doi: 10.1117/1.2080368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bindig U, Gersonde I, Meinke M, Becker Y, Muller G. Fibre-optic IR-spectroscopy for biomedical diagnostics. Spectroscopy-an International Journal. 2003;17:323–344. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bindig U, Meinke M, Gersonde I, Spector O, Vasserman I, Katzir A, Muller G. IR-biosensor: flat silver halide fiber for bio-medical sensing? Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical. 2001;74:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bindig U, Muller G. Fibre-optic laser-assisted infrared tumour diagnostics (FLAIR) Journal of Physics D-Applied Physics. 2005;38:2716–2731. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bindig U, Winter H, Wasche W, Zelianeos K, Muller G. Fiber-optical and microscopic detection of malignant tissue by use of infrared spectrometry. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2002;7:100–108. doi: 10.1117/1.1412439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlton C, Katzir A, Mizaikoff B. Infrared evanescent field sensing with quantum cascade lasers and planar silver halide waveguides. Analytical Chemistry. 2005;77:4398–4403. doi: 10.1021/ac048189a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiacchiera SM, Kosower EM. Deuterium-Exchange on Micrograms of Proteins by Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier-Transform Infrared-Spectroscopy on Silver-Halide Fiber. Analytical Biochemistry. 1992;201:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammody Z, Huleihel M, Salman A, Argov S, Moreh R, Katzir A, Mordechai S. Potential of ‘flat’ fibre evanescent wave spectroscopy to discriminate between normal and malignant cells in vitro. Journal of Microscopy-Oxford. 2007;228:200–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuura Y, Kino S, Yokoyama E, Katagiri T, Sato H, Tashiro H. Flexible fiber-optics probes for Raman and FT-IR remote spectroscopy. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics. 2007;13:1704–1708. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ring A, Schreiner V, Wenck H, Wittern KP, Kupper L, Keyhani R. Mid-infrared spectroscopy on skin using a silver halide fibre probe in vivo. Skin Research and Technology. 2006;12:18–23. doi: 10.1111/j.0909-725X.2006.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simhony S, Kosower EM, Katzir A. Fourier-Transform Infrared-Spectra of Aqueous Protein Mixtures Using a Novel Attenuated Total Internal Reflectance Cell with Infrared Fibers. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1987;142:1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dejong S. SIMPLS - an Alternative Approach to Partial Least-Squares Regression. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 1993;18:251–263. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geladi P, Kowalski BR. Partial Least-Squares Regression - a Tutorial. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1986;185:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wold S, Ruhe A, Wold H, Dunn WJ. The Collinearity Problem in Linear- Regression - the Partial Least-Squares (PLS) Approach to Generalized Inverses. Siam Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing. 1984;5:735–743. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise B, Gallagher N, Bro R, Shaver J, Windig W, Koch R. PLS_Toolbox Version 4.0 Manual. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savitzky A, Golay MJE. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Analytical Chemistry. 1964;36:1627. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chong IG, Chi-Hyuck J. Performance of some variable selection methods when multicollinearity is present. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2005;78:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogomolny E, Huleihel M, Suproun Y, Sahu RK, Mordechai S. Early spectral changes of cellular malignant transformation using Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2007;12:024003. doi: 10.1117/1.2717186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.German MJ, Hammiche A, Ragavan N, Tobin MJ, Cooper LJ, Matanhelia SS, et al. Infrared spectroscopy with multivariate analysis potentially facilitates the segregation of different types of prostate cell. Biophysical Journal. 2006;90:3783–3795. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucassen GW, van Veen GNA, Jansen JAJ. Band analysis of hydrated human skin stratum corneum attenuated total reflectance Fourier transfrom infrared spectra In Vivo. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 1998;3:267–280. doi: 10.1117/1.429890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]