Abstract

Backgrounds and the purpose of the study

Inducible NO synthase activity has been frequently reported in varicose veins. Aminoguanidine is known to inhibit iNOS. The aim of this study was to examine the effects of aminoguanidine on varicocelized rats.

Methods

Male Wistar rats were divided into groups A, B, C, D, E, and F (control group). Groups A, B, C, and D rats underwent left varicocele induction with a 20-gauge needle. Group E (sham) rats underwent a similar procedure, but the renal vein was left intact. Ten weeks after varicocele induction, sperm parameters were evaluated in groups D, E, and F. Groups A and B received 50 mg/kg aminoguanidine or placebo, respectively, daily for 10 weeks. After 10 and 20 weeks of varicocele induction, the fertility outcomes of the experimental groups were evaluated.

Results

The values of the sperm parameters did not differ significantly between groups B and D, but were significant when compared with groups F and E (P≤0.05). The values of the sperm parameters of groups F and E showed no significant changes (P≤0.05). The changes between group A and groups B and D were significant (P≤0.05). Ten weeks after varicocele induction, rats of groups A, B, and C were still fertile. After 20 weeks, only half of the rats in group A were fertile.

Conclusions

Aminoguanidine improved the sperm parameters and mating outcomes in vari-cocelized rats.

Keywords: Aminoguanidine, Sperm, Fertility, Varicocele

INTRODUCTION

Varicocele is characterized by abnormal tortuosity and dilation of the gonadal veins that drain the testis (1–3). The prevalence of varicocele ranges from 15% in the adult male population, among whom 40? have primary infertility and up to 80? have secondary infertility (4, 5). Various mechanisms have been proposed to underlie testicular dysfunction in varicocele, including reflux of adrenal toxic metabolites, testicular hypoxia caused by venous stasis, hormonal deficiency, increased pressure in the internal spermatic vein, and elevated testicular temperature (2, 4, 6). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidative stress, and the physiological rate of formation of nitric oxide (NO) in particular play an important role in certain normal physiological processes in reproduction (7). NO is a free radical gaseous molecule synthesized from the catalytic reaction between l-arginine and different isoforms of NO synthase (NOS)—constitutive neuronal NOS (nNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS), and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) (1, 8–10). iNOS activity has frequently been reported in varicose veins (11). Varicocelectomy in infertile men have resulted in improved levels of various semen parameters and higher pregnancy rates; however, these results have not been conclusively proven. If oxidative stress decreases after varicocelectomy, it would mean that inhibition of NOS synthesis can improve the patient's condition (12). Varicocele is commonly treated with varicocelectomy, but because of the surgical risk involved and the chance of the persistence of infertility, patients are also offered the choice of non-surgical treatment with certain drugs. Aminoguanidine (AG), an inhibitor of iNOS—is believed to exert its pharmacological effects by inhibiting iNOS isoforms (13, 14). AG is a compound structurally similar to l-arginine; it inhibits iNOS in a selective and competitive manner, leading to decrease NO production (15). Moreover, AG shows antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties; which are especially observed in peroxynitrite (ONOO–) production (15–17). However, the influence of AG on varicocele has not been reported yet. The aim of this study was to determine (1) the time required for complete infertility resulting from unilateral varicocele in an experimental varicocele induction model in the rat, (2) AG-induced improvement in the sperm quality in varicocelized rat, and (3) the effect of AG administration for 10 weeks on the infertility of varicocelized rats. Therefore, the sperm parameters and the mating outcomes before and after AG administration were evaluated.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals and Varicocele Induction

A total of 72 adult male and female Wistar rats (300–350 g) were maintained under standard laboratory conditions. After a week of acclimatization under a 12-h light:12-h dark cycle at 22 (2)°C, they were mated to evaluate the mating outcome. Male rats were randomly divided into 6 groups (A, B, C, D, E, and F) with 6 rats in each group. The rats in groups A, B, C, and D underwent left varicocele induction. Group E (sham) rats underwent a similar procedure, but varicocele was not induced. Group F rats were used as the control group. The sperm parameters of groups D, E, and F were evaluated 10 weeks after varicocele induction. Rats in groups A and B were intraperitoneally administered 50 mg/kg AG and placebo, respectively, daily for 10 weeks after varicocele induction. Group C rats were used for the evaluation of mating outcome.

Surgical Procedure

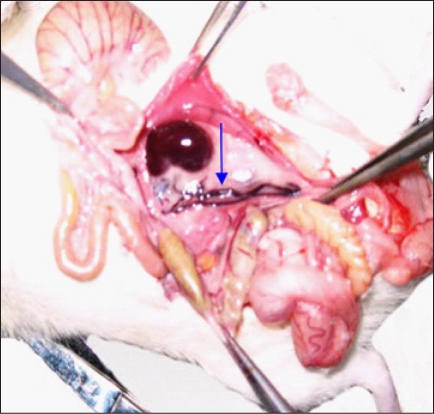

Left varicocele was experimentally induced in the rats of groups A, B, C, and D, as described by Turner (18). In brief, rats were weighed and administered general anesthesia with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (1 mg/kg body weight) (19). Then, the left renal vein was dissected with a midline incision. Two knots were tied around the renal vein at a point medial to the insertion of the spermatic vein by using a 20-gauge needle and a 4-0 silk suture. The needle was carefully removed, and the diameter of the left renal vein was reduced by approximately 50% (8, 18) (Fig. 1). The rats in group E (sham) underwent similar procedure except that no knots were tied around the needle and renal vein. rats of group F were used as controls. The animals in groups D, E, and F were sacrificed 10 weeks after operation, and the mating outcome was evaluated.

Figure 1.

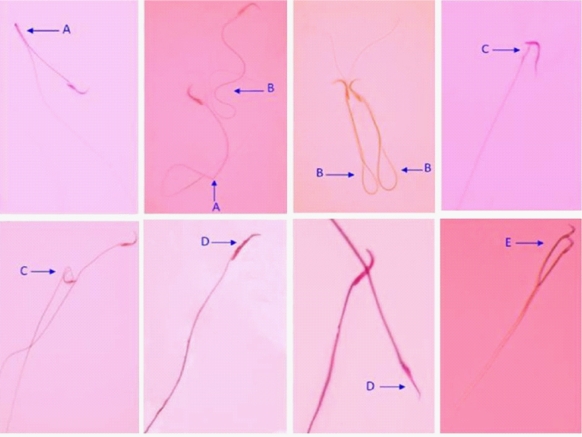

Abnormal sperm morphology. A: Bent tail, B: Coiled tail, C: Bent neck, D: Flattened head, and E: Double head

Treatment

Ten weeks after surgery, the operated animals in group A received 50 mg/kg of AG (Sigma/Aldrich Chemical Co.) for 10 weeks. The drug was dissolved in distilled water and immediately injected intraperitoneally.

Fertility Rate Assay

All rats were mated with fertile female rats after 10 weeks of varicocele induction for evaluation of mating outcome. Ten weeks later (i.e., 20 weeks after the operation), the fertility test was repeated for groups A (treated), B (placebo), and C (varicocele) again. The sperm parameters of groups D, E, and F were evaluated 10 weeks after surgery, and groups A, B, and C were evaluated 20 weeks after varicocele induction.

Sperm Collection

By laparotomy, the left and right caudal parts of the epididymis were carefully separated from the testes, minced in 5 ml of Hanks’ medium, and incubated for 15 min (8). The diluted sperm suspension (10 ml) was transferred to the hemocytometer, and the settled sperm were counted with a light microscope at 400× magnification (million/ml) (20).

Assessment of Epididymal Sperm Parameters Sperm motility

The motility assay was conducted by observing the sperm suspension on a slide glass at 37°C. The percentage of motile spermatozoa was determined by counting more than 200 spermatozoas randomly in 10 selected fields under a light microscope (Olympus BX51, Germany), and the mean number of motile sperm×100/total number of sperms (8, 20) was calculated.

Sperm morphology

The sperm morphology was determined by eosin/nigrosin staining. Ten microliters of eosin Y (1?) and nigrosin was added to 50 µl of sperm suspension. The prepared smear was used after incubation for 45–60 min at room temperature. In each field, 200 sperm were counted under a light microscope (1000×). The sperms were classified on the basis of the following abnormalities: double head, flattened, bent neck, bent tail, and multiple abnormalities (21) (Fig. 1).

Rate of the sperm vitality

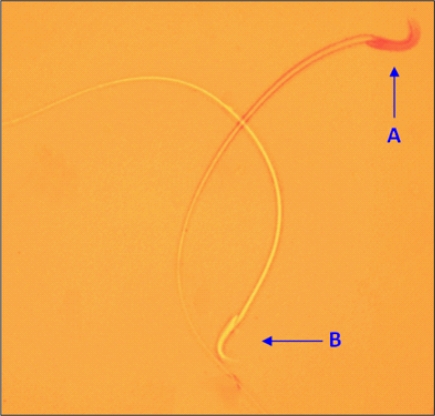

To determine sperm vitality, 40 µl of freshly liquefied semen was thoroughly mixed with 10 µl of eosin Y (1?), and 1 drop of this mixture was transferred to a clean slide. At least 200 sperms were counted at a magnification of 1000× under oil immersion. Sperms that were stained pink or red were considered dead, and those stained unstained were considered viable (22, 23) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Sperm viability. A: Dead sperm, B: Viable sperm

Statistical Analyses

All values were presented as mean (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Duncan test were performed to determine the differences among all groups with regard to all the parameters by using the SPSS/PC program (version 13.0SS).

RESULTS

Assay of the rate of fertility

The members of all 6 groups were still fertile when they mated with female rats 10 weeks after operation. The pups were delivered within 25–30 days. Ten weeks later (20 weeks after varicocele induction), groups A (treated), B (placebo), and C (varicocele) mated again. None of the females were impregnated after mating with male rats of groups B and C, but half of the rats of group A were fertile and hence able to impregnate female rats.

Evaluation of Varicocele

All rats with varicocele showed conspicuous dilatation of the left spermatic vein with blood engorgement. In rats of groups F and E, no dilatation of the spermatic vein was observed (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Spermatic vein. Distended spermatic vein in a varicocele rat (arrow).

Assessment of epididymal Sperm Parameters

The differences in sperm parameters between groups B and D (varicocele groups) were not significant. The sperm count, morphology, motility, and vitality of the left testis of rats of the varicocele group decreased significantly in comparison with those of groups E or F (sham and control) (P≤0.05) (Table 1). In group A (treated), the sperm parameters of the left testis improved significantly in comparison with those of the varicocele group (P≤0.05) (Table 1). However, no significant changes were recorded by comparison of the control and sham groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Epididymal sperm count, motility, and morphology in the experimental groups

| Sperm Viability (%) | Motile sperm (%) | Normal Morphology (%) | Sperm count (×106) | Groups | Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96 (2.6) | 83 (5.4) | 91 (3.45) | 160 (2.2) | Right | Control |

| 90 (1.2) | 78 (6.82) | 89 (3.2) | 155 (3.5) | Left | (F) |

| 86 (3.4) | 85 (4.33) | 88 (4.88) | 151 (8.2) | Right | Sham |

| 91 (3.9) | 77 (10) | 86 (3.02) | 140 (9.2) | Left | (E) |

| 85 (1.1) | 67 (1.62) | 84 (3.89) | 145 (11.1) | Right | Varicocele |

| 70 (4.3)+ | 46 (6.9)+ | 64 (2.4)+ | 83 (8.3)+ | Left | (D) |

| 83 (1.4) | 71 (3.57) | 85 (1.79) | 141 (13.19) | Right | Treatment |

| 81 (2)++ | 69 (4.13)++ | 80 (1.42)++ | 132 (11.4)++ | Left | (A) |

Note. Results are presented as mean (SD).

P≤0.05 compared with groups E and F.

P≤0.01 compared with the varicocele-induced group.

DISCUSSION

Clinical or sub-clinical varicocele has been shown to cause male infertility (2). In such patients, the ROS levels in the serum in testes are increased (1). Increased nitric oxide levels have also been demonstrated in the spermatic veins of patients with varicocele (10). Varicocele, which is the leading cause of male infertility, is associated with increased production of NO and production of spermatozoal ROS (17, 24, 25). It is well documented that the iNOS isoforms elicit a wide spectrum of effects on the function of the testes (8, 26). In this study, when AG was administered, the percentage of progressive motility was the main predictor of fertilization outcome. It was speculated that the relationship between sperm morphology and the results of invitro fertilization depends on the effects of AG. Our results are in agreement with the previous reports on other antioxidant agents. A recent study using dietary vitamin E supplementation showed significantly low level of superoxide and possibly decreased apoptosis in varicocelized rats (27). AG, as a specific iNOS inhibitor, is a potent inhibitor of NO synthesis in all tissues. As reported, in traumatized peritoneal tissues, AG is easily absorbed it passes freely and prevents oxidative stress and conserves mitochondrial function and, it has low levels of toxicity (17, 28). Positive changes in the sperm quality in this study may be because AG directly scavenges hydroxyl radicals and thereby inhibits lipid peroxidation (29). It is possible that interference of AG with free radical generation could be one of the causes of the decline in varicocele repair. Although the concentration of NO in AG-treated rats was not determined in this study but as it has been reported, the action of AG is similar to that of l-arginine, which inhibits iNOS in a competitive manner, leading to a decrease in NO production (15). It is possible that this mechanism could have contributed to reduced levels of NO in AG-injected rats. Our finding suggests that intraperitoneal administration of AG in varicocelized rat successfully increases the sperm quality (30). Although AG has been shown to have antioxidant properties, these properties have not been investigated in model rats in which varicocele was experimentally induced. When AG was administered to group A, the count, motility, vitality, and morphology of the sperm improved significantly compared to those in groups B (placebo) and D (not treated). The results are consistent with the data of Bahmanzadeh et al. When they injected NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) intraperitoneally into varicocelized rats, significant changes were observed in all the sperm parameters except for motility. Under certain pathological conditions, such as varicocele, high NO production can cause formation of a highly toxic anion of peroxidation (peroxynitrite ONOO–) and subsequently reduce sperm motility (30). Moreover, AG has been reported to have peroxynitrite (ONOO–) scavenger property (31). However, the significant relationship between sperm motility and NO production in testicular tissue is controversial. In a previous report, NO was found to reduce the ATP levels by inhibition of ATP synthase in cells; therefore, any reduction in the ATP content might result in poor sperm motility (23). Giardino et al. reported that AG acted as an antioxidant in vivo, preventing free radical formation and lipid peroxidation in cells and tissues and thus preventing oxidant-induced apoptosis (31). Experimentally induced varicocele results in an increase in the rate of formation of NO even when histopathological damage is not observed (12). Administration of AG in this experiment reduced excessive NO formation in varicocelized rats. In previous experiments, the rats remained fertile 10 weeks after induction of varicocele. However, they became infertile after 20 weeks. These results confirm that unilateral varicocele affect fertility only 10 weeks after varicocele induction, and that complete infertility occurs only after a minimum of 5 months after varicocele induction. After injection of AG for 10 weeks, half of the rats in the treated group could impregnate the female rats. It seems that other factors may be involved in infertility following varicocele induction.

CONCLUSION

In the current study, the fertile varicocelized rats became infertile 5 months after varicocele induction. Intraperitoneal administration of AG significantly minimized the damage to the sperm, and rats regained their fertility. The results of this study may support the hypothesis that reduced oxidative damage resulting from AG treatment and the protective actions of AG are consequences of direct and indirect antioxidant activities. Therefore, AG could be useful for the treatment of varicocele and possibly other clinical conditions involving excess free radical production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences, grant No 88-01-30-8370.

References

- 1.Agarwal A, Sharma RK, Desai NR, Prabakaran S, Tavares A, Sabanegh E. Role of oxidative stress in pathogenesis of varicocele and infertility. Urology. 2009;73(3):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koksal IT, Tefekli A, Usta M, Erol H, Abbasoglu S, Kadioglu A. The role of reactive oxygen species in testicular dysfunction associated with varicocele. BJU Int. 2000;86(4):549–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner TT, Lysiak JJ. Oxidative stress: a common factor in testicular dysfunction. J Androl. 2008;29(5):488–498. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumer CG, Fariello RM, Restelli AE, Spaine DM, Bertolla RP, Cedenho AP. Sperm nuclear DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial activity in men with varicocele. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5):1716–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith R, Kaune H, Parodi D, Madariaga M, Rios R, Morales I, Castro L. Increased sperm DNA damage in patients with varicocele: relationship with seminal oxidative stress. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(4):986–993. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marmar JL. Varicocele and male infertility: Part II: The pathophysiology of varicoceles in the light of current molecular and genetic information. ESHRE. 2001;7(5):461–472. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdamar AS, Soylu AG, Culha M, Ozden M, Gokalp A. Testicular oxidative stress. Effects of experimental varicocele in adolescent rats. Urol Int. 2004;73(4):343–347. doi: 10.1159/000081596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng D, Zheng XM, Li SW, Yang ZW, Hu LQ. Effects of epidermal growth factor on sperm content and 8. motility of rats with surgically induced varicoceles. Asian J Androl. 2006;8(6):713–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2006.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amiri I, Sheike N, Najafi R. Nitric oxide level in seminal plasma of fertile and infertile males and its correlation with sperm parameters. DARU. 2006;14(4):197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comhaire FH, Mahmoud AM. Editorial commentary on: Cavallini G, Ferraretti AP, Gianaroli L, Biagiotti G, Vitali G. Cinnoxicam and L-carnitine/acetyl-L-carnitine treatment for idiopathic and varicocele-associated oligoasthenospermia. J Androl. 2004;25:761–770. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santoro G, Romeo C, Impellizzeri P, Ientile R, Cutroneo G, Trimarchi F, Pedale S, Turiaco N, Gentile C. Nitric oxide synthase patterns in normal and varicocele testis in adolescents. BJU Int. 2001;88(9):967–973. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.02446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Stefani S, Silingardi V, Micali S, Mofferdin A, Sighinolfi MC, Celia A, Bianchi G, Giulini S, Volpe A, Giusti F, Maiorana A. Experimental varicocele in the rat: early evaluation of the nitric oxide levels and histological alterations in the testicular tissue. Andrologia. 2005;37(4):115–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2005.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh DY, Feng NH, Chen CF, Lin HI, Wang D. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expressions in different lung injury models and the protective effect of aminoguanidine. Transplant. 2008;40(7):2178–2181. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dambrova M, Kirjanova O, Baumane L, Liepinsh E, Zvejniece L, Muceniece R, Kalvinsh I, Wikberg Je. EPR investigation of in vivo inhibitory effect of guanidine compounds on nitric oxide production in rat tissues. J Pharmacol. 2003;54(3):339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misko TP, Moore WM, Kasten TP, Nickols GA, Corbett JA, Tilton RG, McDaniel ML, Williamson JR, Currie MG. Selective inhibition of the inducible nitric oxide synthase by aminoguanidine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;233(1):119–125. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90357-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ihm SH, Yoo HJ, Park SW, Ihm J. Effect of aminoguanidine on lipid peroxidation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Metabolism. 1999;48(9):1141–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiomi M, Wakabayashi Y, Sano T, Shinoda Y, Nimura Y, Ishimura Y, Suematsu M. Nitric oxide suppres sion reversibly attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction and cholestasis in endotoxemic rat liver. Hepatology. 1998;27(1):108–115. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner TT. The study of varicocele through the use of animal models. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7(1):78–84. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cam K, Simsek F, Yuksel M, Turkeri L, Haklar G, Yalcin S, Akdas A. The role of reactive oxygen species and apoptosis in the pathogenesis of varicocele in a rat model and efficiency of vitamin E treatment. Int J Androl. 2004;27(4):228–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seed J, Chapin RE, Clegg ED, Dostal LA, Foote RH, Hurtt ME, Klinefelter GR, Makris SL, Perreault SD, Schrader S, Seyler D, Sprando R, Treinen KA, Veeramachaneni DN, Wise LD. Methods for assessing sperm motility, morphology, and counts in the rat, rabbit, and dog: a consensus report. ILSI Risk Science Institute Expert Working Group on Sperm Evaluation. Reprod Toxicol. 1996;10(3):237–244. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(96)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayana K, Prashanthi N, Nayanatara A, Kumar HH, Abhilash K, Bairy KL. Effects of methyl parathion (o,o-dimethyl-o-4-nitrophenyl phosphorothioate) on rat sperm morphology and sperm count, but not fertility, are associated with decreased ascorbic acid level in the testis. Mutat Res. 2005;588(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Björndahl L, Söderlund I, Kvist U. Evaluation of the one-step eosinnigrosin staining technique for human sperm vitality assessment. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(4):813–816. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisa U, Basar MM, Ferhat M, Yilmaz E, Basar H, Caglayan O, et al. Testicular tissue nitric oxide and thiobarbituric acid reactive substance levels: evaluation with respect to the pathogenesis of varicocele. Urol Res. 2004;32(3):196–199. doi: 10.1007/s00240-004-0401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagliaro P. Differential biological effects of products of nitric oxide synthase: it is not enough to say NO, in Life sciences. Else. 2003;73(17):2137–2149. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00593-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehraban D, Ansari M, Keyhan H, Sedighi Gilani M, Naderi G, Esfehani F. Comparison of nitric oxide concentration in seminal fluid between infertile patients with and without varicocele and normal fertile men. Urol J. 2005;2(2):106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turkyilmaz Z, Gulen S, Sonmez K, Karabulut R, Dincer S, Can Basaklar A, kale N. Increased nitric oxide is accompanied by lipid oxidation in adolescent varicocele. Int J Androl. 2004;27(3):183–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vakili A, Nekooeian A, Dehghani GA. Aminoguanidine reduces infarct volume and improves neurological dysfunction in transient model of focal cerebral ischemia in rat. DARU. 2006;14(1):126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustafa A, Gado AM, Al-Shabanah OA, Al-Bekairi AM. Protective effect of aminoguanidine against paraquat-induced oxidative stress in the lung of mice. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;132(3):391–397. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0456(02)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahmanzadeh M, Abolhassani F, Amidi F, Ejtemaiemehr Sh, Salehi M, Abbasi M. The effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitor (L- NAME) on epididymal sperm count, motility, and morphology varicocelized rat. DARU. 2008;16(1):23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szabó C, Ferrer-Sueta G, Zingarelli B, Southan GJ, Salzman AL, Radi R. Mercaptoethylguanidine and guanidine inhibitors of nitric-oxide synthase react with peroxynitrite and protect against peroxynitrite-induced oxidative damage. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(14):9030–9036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giardino I, Fard AK, Hatchell DL, Brownlee M. Aminoguanidine inhibits reactive oxygen species formation, lipid peroxidation, and oxidant-induced apoptosis. Diabetes. 1998;47(7):1114–1120. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.7.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]