Abstract

Background

Detection of a small number of circulating tumor cells is important, especially at the early stages of cancer. The small number of CTCs is hard to detect as very few approaches are sensitive enough to differentiate these from the pool of other cells. Improving the affinity of a selective surface-functionalized molecule is important given the sparsity of CTCs in vivo. There are a number of proteins and aptamers that provide such a high affinity but using a surface nano-texturing increases this affinity even further.

Method

This work reports an approach to improve affinity of tumor cell capture by using novel aptamers against cell-membrane over-expressed Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors (EGFR) on a nano-textured polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate. Surface immobilized aptamers are used to specifically capture tumor cells from physiological samples.

Results

The nano-texturing of PDMS increased surface roughness at the nanoscale. This increased the effective surface area and resulted in a significantly higher degree of surface functionalization. The phenomenon resulted in increased density of immobilized EGFR specific RNA aptamer molecules and provided significantly higher efficiency to capture cancer cells from a mixture. The data showed that CTCs could be captured and enriched leading to higher yield, yet higher background.

Conclusion

The comparison of glass slides, plain PDMS and nano-textured PDMS functionalized with aptamers show that a two-fold approach of using aptamers on nano-textured PDMS can be an important factor for cancer cytology devices especially for the idea of lab-on-chip towards higher yield in capture efficiency.

Keywords: RNA Aptamers, CTC, Human Glioblastoma, Polydimethylsiloxane, Lab-on-Chip, Nano-textured Materials, Microscopy, Basement Membrane

Introduction

Cancer mortality can be significantly reduced by developing methods for early detection and prevention [1, 2]. A number of strategies for detection and isolation of tumor cells has been reported [3–9]. Detection and sorting based on affinity interactions, especially with aptamers, can yield higher efficiency and greater specificity [10]. Aptamers have been shown to have better affinities and higher specificities than those of antibodies [11]. Anti-EGFR RNA aptamer substrates can specifically recognize, capture and isolate human glioblastoma (hGBM) cells, known to over-express EGFR, from a mixture of fibroblasts [12]. The “mean capture yield” can be increased by forcing the sample to run over the substrates for multiple times. However, it takes more time and may also decrease the specificity.

It is well known that the basement membrane can anchor a cancer cell to its loose underneath connective tissue through cell adhesion molecules known as integrins [13]. The natural nano-structured characteristics of the basement membrane can improve cell adhesion and growth [14, 15]. In the case of cancer cells, for their normal proliferation they have to appropriately attach to the matrix first [16]. In tissue engineering, researchers have tried to mimic the nano-scale topography of native tissue to increase the cell proliferation on scaffolds [17, 18]. The results show that the nano-structured scaffolds can specifically and significantly improve densities of certain cells[18].

PDMS has been one of the most actively used polymers for biological research. It is easy to manipulate and its stable chemical and physical properties make it vitally important in cell experiments [19].

In this paper the 3D nano-textured PDMS substrates are prepared and then the substrates are functionalized with anti-EGFR aptamers for cell isolation. Both of these factors increase the affinity of the surface. We show that the nanoscale topography of PDMS provides an additional factor to increase affinity for cancer cell attachment, as it provides larger surface area for aptamer immobilization and increases the number of available aptamers on the surface for cell capture. The data presented here provides a solid proof that nano-textured substrates can significantly improve the cancer cell isolation and sensitivity, without significant decrease in specificity. 3D nano-texturing provides a much better probability of capturing and isolation of small number of tumor cells from solution. This can be helpful in developing novel cytological tools for CTC detection.

Materials and Methods

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

Aptamer Preparation

Purified human EGFR (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used for anti-EGFR RNA aptamer preparation via selecting binding species [20, 21]. The EGFR protein was purified from murine myeloma cells, and contained the extracellular domain of human EGFR (Leu25-Ser645) fused to the Fc domain of human lgG1 (Pro 100-Lys 330) via a peptide linker (IEGRMD). The anti-EGFR aptamer(Kd = 2.4 nM) and a mutant aptamer were extended with a capture sequence. The extended capture sequence did not participate in aptamer hairpin structure but was used to immobilize aptamer on the substrate through duplex formation with substrate-anchored DNA probe molecules. The sequences of the extended anti-EGFR aptamer, extended mutant aptamer, and substrate anchored probe were: anti-EGFR aptamer (5′-GGC GCU CCG ACC UUA GUC UCU GUG CCG CUA UAA UGC ACG GAU UUA AUC GCC GUA GAA AAG CAU GUC AAA GCC GGA ACC GUG UAG CAC AGC AGA GAA UUA AAU GCC CGC CAU GAC CAG-3′); mutant aptamer (5′-GGC GCU CCG ACC UUA GUC UCU GUU CCC ACA UCA UGC ACA AGG ACA AUU CUG UGC AUC CAA GGA GGA GUU CUC GGA ACC GUG UAG CAC AGC AGA GAA UUA AAU GCC CGC CAU GAC CAG-3′); substrate anchored probe(5′-amine-CTG GTC ATG GCG GGC ATT TAA TTC-3′). The extended capture sequence is underlined. The aptamer was modified by extending the DNA template at its 3′ end with a 24 nt sequence tag, and then hybridizing the transcribed, extended aptamer with a complementary substrate-anchored probe modified with an amine at its 5′ end.

Preparation of Nano-textured PDMS Substrates

Half a gram of ploy(lactic acid)/poly(glycolic acid) (PLGA; 50/50 wt%; 12–16.5×103 MW; Polysciences, Inc.) was dissolved in 8 ml of chloroform at 55°C for 40 min [17, 22]. The solution was cast into glass petri dish, allowed to sit overnight, and was put into a vacuum chamber (15 in Hg) for 2 days at room temperature. The solid PLGA polymers were treated with 10 N NaOH for 1 h to generate nano-textured surfaces [17], and further sterilized by soaking in ethanol for 24 h followed by exposure to UV light for 1h. SYLGARD 184 Silicon Elastomer (Dow Corning, Midland, MI)was mixed (10:1,wt/wt) with a silicon resin curing agent. The mixture was placed in a vacuum chamber to remove all bubbles, and then cast onto NaOH treated PLGA polymer surface. It was then allowed to cure for 48 h at room temperature to solidify. Finally, the PDMS was peeled from the PLGA. Before the surface modification, the PDMS substrates were immersed into deionized (DI)water at 37 °C overnight to completely remove any residual PLGA.

The organic solvents such as methanol and acetonitrile could cause PDMS bulk to dissolve and swell. The solubility parameters of ethanol and acetone are 12.7 and 9.9 cal1/2cm−3/2 respectively, and solvents that have a solubility parameter similar to that of PDMS (7.3 cal1/2cm−3/2) generally swell PDMS more [23]. Solubility parameters of methanol and acetonitrile are 14.5 and 11.9 cal1/2cm−3/2 respectively, and the swelling ratios are 1.02 and 1.01 respectively, less than that of ethanol and acetone (1.06 and 1.04 respectively). Methanol and acetonitrile were thus used for PDMS surface modifications. Further, although methanol and acetonitrile can completely dissolve PDMS, process takes an extremely long time. Even diisopropylamine, which has swelling ratio as high as 2.13, still need one month to completely dissolve the PDMS. The silanization and isothiocyanate molecule incubations were thus done for only 20 to 30 min, so that the swelling and dissolving of PDMS were insignificant.

SEM and AFM Characterization

Zeiss Supra 55 VP scanning electron microscope was used to qualitatively evaluate PDMS surface topography (Fig. 1(D) inset). Samples were sputter-coated with gold at room temperature. Surface topography was quantitatively evaluated using Dimension 5000 AFM. The changes in surface area and root mean square surface roughness were measured. Height images of PDMS samples were captured in the ambient air at 15–20% humidity at a tapping frequency of approximately 300 kHz. The analyzed field was 3 μm × 3 μm at a scan rate of 1Hz and 256 scanning lines.

Figure 1.

The surface roughness of PLGA and PDMS cast on PLGA increased after NaOH etching. The AFM micrographs (3 × 3 μm2) of (A) untreated PLGA; (B) PLGA after 10 N NaOH etch for 1 hour. The surface roughness increased from 22 nm on untreated PLGA to 310 nm on nano-textured PLGA surface. The AFM micrographs (8 × 8 μm2) of (C) Nano-textured PDMS surface (roughness: 347 nm); and (D) Nano-textured PDMS after APTES and thiophosgene modification (roughness: 289 nm). Inset to (D) shows SEM micrograph of NaOH treated PLGA surface. The scale bar is 100 μm.

Attachment of Anti-EGFR Aptamer on PDMS and Glass Substrates

The attachment method was adopted from earlier descriptions [21, 24–26]. The PDMS substrates and the glass slides were cut into 5×5 mm2 pieces and cleaned with UV-Ozone plasma and piranha solution (H2O2:H2SO4 in a 1:3 ratio) for 30 and 10 minutes respectively. After rinsing with DI water and drying in nitrogen flow, the PDMS and glass substrates were immersed in 2% (v/v) of 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) in methanol for 30 min at room temperature. The substrates were then sequentially rinsed with methanol and DI water. The amino groups on PDMS and glass substrates were converted to the isothiocyanate groups by introducing a 0.5% (v/v) thiophosgene solution in acetonitrile for 20 min at 40 °C. The substrates were then washed with DI water and dried in a stream of nitrogen. The amino modified DNA capture probes were prepared at 30 μM concentration in 5 mM tris buffer with 50 mM NaCl. A volume of 5 μl of DNA solution was placed on each substrate and allowed to incubate in a humidity chamber at 37 °C overnight. Each substrate was then washed with DI water. Salmon sperm DNA was used for prehybridization to reduce RNA physical adsorption. A volume of 5 μl anti-EGFR RNA aptamer at 1 μM concentration was placed on each substrate in 1× annealing buffer (10 mM pH 8.0 Tris, 1 mM pH 8.0 EDTA, 100 mM NaCl). After 1 hour of hybridization at 37 °C, substrates were washed with 1× annealing buffer and DI water for 5 minutes. The negative control devices were hybridized with mutant aptamer using the same protocol. The substrates were placed in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 5 mM magnesium chloride (pH 7.5) and used immediately.

Contact Angle Measurements

Contact angles were measured on isothiocyanate group modified PDMS (with/without nano-texturing), unmodified PDMS (with/without nano-texturing), and glass (with/without isothiocyanate groups modification). A droplet of DI water was placed on the surface of the substrate at room temperature, and after 30 s, the contact angle was measured using a contact angle goniometer (NRL-100, Rame-Hart). Average of five measurements were calculated for each run.

Fluorescence Measurements of Fluorescamine

Surface modification was further confirmed by fluorescence measurements of Fluorescamine. The density of surface-grafted amino groups from APTES was measured by fluorogenic derivatization reaction with Fluorescamine [27]. A mixture of 900 μl of 0.1% (w/v) Fluorescamine dissolved in acetone, 150 μl of 0.1 M borate buffer and 1.91 ml DI water was made. After APTES modification, Glass, PDMS and nano-textured PDMS samples were immersed into fluorescamine mixture solution for 5 min at room temperature. All samples were rinsed with acetone to remove the excessive reagents. The fluorescence measurements were taken at 390 nm wavelength using Zeiss Confocal Microscope. The fluorescence intensities were analyzed with Image J software.

Human Glioblastoma and Meninge Derived Primary Fibroblast Cell Culture

The hGBM cells were cultured in a chemically defined serum-free medium: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DMEM)/F-12 medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml mouse EGF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), 20 ng/ml of bFGF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), 1× B27 supplement (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1× Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium-× (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), Penicillin:Streptomycin (100 units/ml:100 μg/ml) (HyClone, Wilmington, DE, USA) and plated at a density of 3×106 live cells/60 mm plate. The hGBM cells were stably transduced with a lentivirus expressing m-cherry fluorescent protein. The primary rat meninge derived fibroblasts were plated in T-75 tissue culture flasks in DMEM/F-12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum.

Tumor Cell Capture on Substrates

The cell suspensions were centrifuged, the supernatants were removed and sterilized 1 × PBS solution (with 5 mM MgCl2) was added to dilute the cells. About 500 μl of cell suspension in 1 × PBS was placed on each substrate surface. The substrates were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, and then washed with sterilized 1X PBS on a shaker at 90 rpm for 15 min [28]. For tumor specific isolation studies, the hGBM cells were mixed with fibroblasts in a 1:1 ratio.

Results and Discussion

Surface Topography of Nano-textured Substrates

The effects of NaOH concentration and etching times have been characterized before [17, 18]. PLGA bulk surface was etched with 10 N NaOH for 1 h to generate nano-textured surface. First, the average surface roughness of PLGA substrates was quantitatively analyzed with AFM (Fig. 1(A)and 1(B)). The surface roughness increased from 22 nm on untreated PLGA to 310 nm on nano-textured PLGA after NaOH etching. The micrographs of PDMS cast on these two substrates are shown in Figs. 1(C) and 1(D). The nano-textured surfaces created on PDMS, before and after chemical modification, showed roughnesses of 347 and 289 nm, respectively.

Contact Angle Measurements

The contact angle data of a water droplet gives a measure of the hydrophobicity of a surface [26]. We measured the contact angles of each substrate. The average of contact angles (n=10) and standard deviations are shown in Table 1. After APTES and isothiocyanate modification, all three types of substrates showed hydrophilic surfaces. The aptamer immobilization would further decrease the contact angle and make these substrates more hydrophilic. The hydrophilic surfaces are known to have lower protein and cell physical adsorption. Moreover, the roughness of a surface can significantly affect contact angle [29]. In other words, the contact angle decreases on a nano-textured hydrophilic surface while it increases on a nano-textured hydrophobic surface. Even with more hydrophilic nano-textured surface, we saw tumor cell isolation.

Table 1.

Contact angles measured immediately after UV-Ozone treatment of the substrates and chemical activation with PDITC, for each of the substrates employed in this study.

| Substrate Type | Contact Angles ± Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Base Substrate | After PDITC treatment resulting in -N=C=S groups on the surface | |

| Glass | 46° ± 1° | 51° ±1° |

| PDMS No Nano-texturing | 115° ± 2° | 59° ±2° |

| PDMS with Nano-texturing | 144° ± 4° | 46° ± 3° |

PDMS initially has methyl groups on both side of backbone, but after UV-Ozone treatment, the methyl groups are substituted with hydroxyl groups. The residual methyl groups on the PDMS surface still contribute to hydrophobicity, as a result the PDMS surface contact angle was higher than that for glass surface even after APTES and isothiocyanate group modification (Table 1). Due to increased surface roughness, the nano-textured PDMS substrate had the largest contact angle [30], but this decreased to a lowest number after APTES and isothiocyanate modification (from 144° to 46°). The etching of NaOH created an anisotropic surface on PLGA which in turn produced the same effect on PDMS when it was casted on PLGA. The strong anisotropy of the nano-textured PDMS surface caused the contact angle to vary, thus the standard deviation of nano-textured PDMS was also higher than that for other groups[31].

The hydroxyl groups on PDMS surface, created after the surface oxidation, can gradually change back to methyl groups, some times in very short period of time [32, 33]. It was thus important to carry out the subsequent chemical modification relatively quickly after UV-Ozone treatment of PDMS. Additionally, it is worth noting that long UV-Ozone treatment (over 90 min) can make the PDMS stiffer and create lots of tiny cracks on the surface [34, 35]. In these experiments, the PDMS surfaces were treated with UV-Ozone for just 30 minutes, minimizing such textural aberrations[36].

Fluorescence Measurements

Proper oxidization of the PDMS surface can significantly increase the number of hydroxyl groups, and further increase the number of available amino groups from APTES and finally improve the total number of immobilized aptamers. The relative amount of amino groups on different samples was determined by comparing the relative fluorescence intensities of Fluorescamine on each sample. More available amino groups on the surface improved the total number of immobilized aptamers, which favored the tumor cell isolation. Fluorescamine is intrinsically non-fluorescent, but its reaction with amino groups results in highly fluorescent derivatives. The glass substrates already had hydroxyl groups on the surface so these underwent only the amine treatment.

The average fluorescence intensities of three types of samples are shown in Table 2. Nano-textured PDMS shows the highest intensity 83.9 ± 14.1 (a.u). The nano-textured surface increased the effective surface area. As a result, the nano-textured surface generated a significantly higher number of hydroxyl groups compared to that on the plain PDMS or glass surfaces, thus more amino groups were introduced on the surface after silanization. The amino group concentration has been shown to reach 4 ×10−8 mol/cm2 [37].

Table 2.

Fluorescence intensity data for glass, PDMS and nano-textured PDMS after APTES & fluorescamine modification (in arbitrary units)

| Substrate Type | Fluorescence Intensity (a.u.) |

|---|---|

| Glass | 4.7 ± 1.5 |

| PDMS without Nano-texturing | 52.7 ± 6.3 |

| PDMS with Nano-texturing | 83.9 ± 14.1 |

The increased number of available aptamers on the surface was favorable for tumor cell isolation. On planar substrates, the density of the anchored probe DNA can be around 1 per 4–5 nm2 [38]. The packing density is a function of the radius of gyration of the probe molecules which defines the footprint a probe molecule can have and thus how packed the molecules can be [39]. On the nanotextured surface we have two advantages. First, we can have reduced distance between immobilized ends of the probes as the free ends have more room on a curvaceous surface and thus need smaller footprint than that on a plane surface for the same radius of gyration. Thus, the probe density would be a whole lot more on the curvaceous surfaces. Secondly, on the nano-textured substrate we have more effective area than the area available on a plane surface of same cross-sectional area. Reduced distance between adjacent probes and larger effective area provides very high probe packing density. The non-specific adsorption of aptamers on surface would occur from Van der Waals forces, only if aptamers could find their way to the surface. The negative charges from the tightly packed DNA probes on the surface repelled the aptamers from inserting into the spaces between adjacent probes and therefore impeded aptamers from reaching the surface of the substrates, where these could bind non-specifically. However, on nano-textured PDMS surfaces, the upper space between probes was widened due to the effectively curvaceous surface that stemmed from nano-texturing, and significantly larger effective surface area increased the total number of probes reducing non-specific aptamer adsorption, but increasing more densely packed aptamers.

Isolation of hGBM Cells

Figure 2 (A) to (F) depict representative images of the hGBM cells captured on glass, PDMS and nano-textured PDMS substrate with anti-EGFR or mutant aptamers. The average density of cells on substrates before washing was 400.9 per mm2 (S.D.: 43.3). All substrates were washed with 1 × PBS at 90 rpm for 15 min. Fluorescent images of cells on 10 substrates of each type were taken. The quantitative analysis results are shown in Figure 2(G). On average 149.6 hGBM cells were captured per mm2 on anti-EGFR aptamer modified nano-textured PDMS substrate (S.D.: 12.2). On the other hand, 79.3 cells per mm2 (S.D.: 11.5) and 37.4 per mm2 (S.D.: 10.1) were captured on anti-EGFR aptamer modified glass and PDMS substrates respectively. There are four major factors which influence the cell capture: the available number of anti-EGFR aptamer molecules on the substrate; the EGFR density on the cell membrane; the affinity between the EGFR and aptamer; and the surface quality of the substrate. We deduce that available number of aptamer molecules is a direct function of surface nano-texturing. Cell isolation efficacy can be improved by increasing the affinity between surface bound aptamer and the over-expressed EGFR. In this case the higher affinity comes from nano-texturing which increases the quantity of aptamers on the surface.

Figure 2.

The hGBM cells on the anti-EGFR and mutant aptamer modified glass, PDMS and nano-textured PDMS substrates. Substrates were incubated with hGBM and washed with PBS. The hGBM cell densities (number of cells per mm2) on the anti-EGFR aptamer modified (A) glass, (C) PDMS and (E) nano-textured PDMS substrates are 79.3 (S.D.: 11.5), 37.4 (S.D.: 10.1), and 149.6 (S.D.: 12.2) respectively; the cell densities on the mutant aptamer modified (B) glass, (D) PDMS and (F) nano-textured PDMS substrates are 2.2 (S.D.: 1.2), 0.6 (S.D.: 0.8), and 25.6 (S.D.: 6.2) respectively; (*P<0.05). (G) Plot shows average hGBM cell density on each type of substrate. The table in the inset depicts actual numbers used in the plot. The scale bar is same for all images and it shows 100 μm.

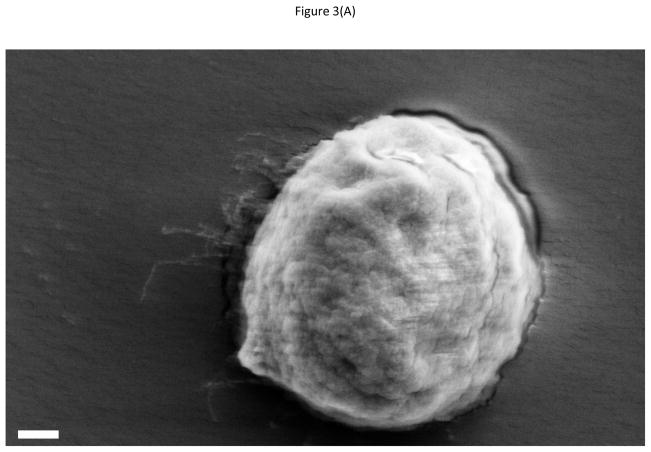

The Fluorescamine analysis demonstrated that the nano-textured PDMS could generate more hydroxyl groups after oxidization and therefore more amino groups from APTES could be attached on the surface after silanization, resulting into increased number of available anti-EGFR aptamer molecules. Thus, the density of immobilized anti-EGFR aptamer increased. In addition, the nano-textured surface did mimic the basement membrane, facilitating cell attachment. Thus, the number of captured cells on the nano-textured PDMS substrate was higher than the other two groups. As discussed before, flat PDMS surface can also generate more hydroxyl groups after oxidization, and a few nanometers of rough texturing can be achieved with long UV-Ozone treatment [40]. However, on a flat PDMS surface, even after chemical functionalization, it is still a major challenge to maintain cells on the surface, especially in long-term cell culture on PDMS, because stable cell-adhesive layer is not easy to form [41]. Moreover, the generated hydroxyl groups undergo dehydration reaction and reform Si-O-Si bonds, and the high chain mobility pulls the hydrophobic methyl groups to the surface. These two factors can prohibit stable cell-adhesive layer formation. Thus the number of captured cells on PDMS surface is lower than that on glass and nano-textured PDMS surface. This can happen on nano-textured PDMS substrate also, however, the nano-texturing itself provides a trade-off by improving cell attachment and isolation. As the data shows, nano-textured surfaces show improved cancer cell isolation, but the non-specific cell attachment also increases. Increased surface area provides more sites not only for protein adsorption but also for focal contact adhesion sites used by cells to attach onto the surfaces. The nano-textured surfaces are thus better suited for overall cell adhesion goals. In the control group, cell density on mutant aptamer modified nano-textured PDMS substrate was 25.6 per mm2 (S.D.: 6.2), almost 12 times higher than that on a glass substrate. Obviously, the higher physical absorption decreases the isolation specificity, but it also significantly improves the detection sensitivity. In practical applications, the selection of material and surface texture depends on the competing goals of isolation sensitivity and specificity. Figure 3 shows the captured cells on the PDMS, nano-textured PDMS and glass surfaces. After 30 min incubation, hGBM cells formed pseudopods that indicated that cells could firmly attach on the nano-textured PDMS surfaces. The same phenomenon was not seen on smooth PDMS surfaces. On the other hand, morphology of hGBM cells on nano-textured PDMS surface was flatter than that on smooth glass and PDMS surfaces. Cells showed globular shape from strong repulsion from the hydrophobic PDMS surface. Although cells on glass surface could also form pseudopods and showed semi-elliptical shape, the whole cell did not spread well as it did on nano-textured PDMS surface. In short, the phenomenon of spreading was more pronounced on nano-textured PDMS than that on smooth PDMS or glass. The topography of substrate resulted in differential cell spreading showing much more distinct behavior on the nano-textured PDMS. On the other hand, cells on smooth PDMS & glass surface still maintained a round or semi-elliptical shape. This serves as a novel and important cytological behavior that can help identify CTCs from the captured cells.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of captured tumor cells on (A) PDMS, (B) nano-textured PDMS, and (C) glass substrate. Micrographs show that cells firmly attach on the rough surface which mimic the basement membrane structure. The scale bar in (A)is 1 μm and it is same for all figures. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 h, and then the substrates were immersed into 20%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 85%, 95% and 100% (v/v) ethanol concentration gradient solution (15 min in each solution). All substrates were lyophilized overnight.

Isolation of hGBM Cells from Cell Mixture

A mixture of hGBM and fibroblast cells was prepared in a ratio of 1:1. The average density of plated cells on the surface was 332.3 per mm2 (S.D.: 23.6). The aptamer functionalized nano-textured PDMS substrates were incubated in the cell mixture, washed and imaged. Both differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescent images were taken. Fig. 4(a) and 4(b) show micrographs from random area of the nano-textured PDMS substrate. There were about 18.4% hGBM cells from 10 substrates (S.D: 9.1) that did not show any fluorescence, although these were expressing m-Cherry fluorescent protein. The data from the mixture group showed no fluorescence from about 31% cells from 10 substrates (846 out of 2729 cells in the mixture of hGBM and fibroblast cells, Average: 58.8 per mm2, S.D: 21.4). The cells that did not show up in fluorescence images included captured non-fluorescent hGBM (18.4% of total hGBM cells) and non-specifically bound fibroblast cells. So the numbers of hGBM and fibroblast cells were 2307.6 and 421.4 respectively. On average about 15.4% cells captured were fibroblast cells. Thus the aptamer functionalized nano-textured PDMS could selectively isolate and enrich a 1:1 mixture suspension of fibroblasts and cancer cells to 1:5.5 on the surface. In comparison to the previous work on smooth glass substrate [21], the ratio of hGBM and fibroblast decreased from 1:8.24 (for glass) to 1:5.5 (for nano-textured PDMS). It indicates that the nano-textured PDMS substrates also led to attachment of fibroblast cells. The increased number of fibroblasts could then be attributable to the nano-texturing and higher number of available aptamers on the surface which would also bind to the EGFR on fibroblasts’ surfaces. Although the nano-textured PDMS substrate increased the attachment of fibroblast, in any case it still could specifically capture hGBM and improve the ratio from 1:1 to 1:5.5. The increased sensitivity decreases its specificity but the trade-off is to the advantage of isolating as many of the small number of cancer cells as possible. In practical applications, the selection of material and surface structure depends on the goals of isolation sensitivity or specificity.

Figure 4.

The hGBM and fibroblast cells on the nano-textured PDMS substrates. Substrates were incubated with a mixture of hGBM and fibroblast and washed with PBS. (A) and (B) are DIC and fluorescent images respectively from the same position on the substrate. The circles in (A) indicate a few fibroblasts that were captured and cannot be seen in (B). The scale bar is 100 μm.

Conclusions

It is demonstrated that anti-EGFR RNA aptamer modified nano-textured PDMS substrates can capture more hGBM cells compared to traditional smooth glass substrates; moreover, the nano-textured PDMS substrate can still specifically recognize, capture and isolate hGBM cells from a mixture of fibroblasts. The nano-textured surface simulates the basement membrane structure and can facilitate tumor cell isolation. This can have important implications for chip-based cancer cell isolation substrate selection.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported with NSF CAREER grant (ECCS-0845669), Welch Foundation grant F-1654 and NCI Award Number 5R01CA119388-05.

This work was supported with NSF CAREER grant (ECCS-0845669) to SMI. YTK acknowledges support from UTA Nano-bio cluster program. ADE acknowledges support from Welch Foundation grant F-1654 and National Cancer Institute Award Number 5R01CA119388-05. Authors would like to thank Michelle Byrom, Melissa Johnson and Ryan Boettger for useful discussions and help with the editing.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: There are no financial disclosures from any author.

References

- 1.Curry SJ, et al. In: Fulfilling the potential of cancer prevention and early detection. Council NR, editor. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RA, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2006. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2006;56(1):11. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swennenhuis JF, et al. Characterization of circulating tumor cells by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytometry Part A. 2009;75A(6):520–527. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharmasiri U, et al. Microsystems for the Capture of Low-Abundance Cells. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. 2010;3(1):409–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.111808.073610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan S, et al. Microdevice for the isolation and enumeration of cancer cells from blood. Biomedical Microdevices. 2009;11(4):883–892. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald MP, et al. Cell cytometry with a light touch: Sorting microscopic matter with an optical lattice. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents. 2004;18(2):200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagrath S, et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1235–1239. doi: 10.1038/nature06385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer NO, et al. Aptasensors for biosecurity applications. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2007;11(3):316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams AA, et al. Highly efficient circulating tumor cell isolation from whole blood and label-free enumeration using polymer-based microfluidics with an integrated conductivity sensor. Journal of American Chemical Society. 2008;130(27):8633–8641. doi: 10.1021/ja8015022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toner M, Irimia D. BLOOD-ON-A-CHIP. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2005;7(1):77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.011205.135108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunka DHJ, Stockley PG. Aptamers come of age - at last. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2006;4(8):588–596. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan Y, et al. Aptamer-based Lab-on-Chip for Cancer Cell Isolation; ASME 2010 First Global Congress on NanoEngineering for Medicine and Biology (NEMB 2010); Houston. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liotta LA, et al. Metastatic potential correlates with enzymatic degradation of basement membrane collagen. Nature. 1980;284(5751):67–68. doi: 10.1038/284067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruoslahti E. How cancer spreads. Scientific American Magazine. 1996;275(3):72–78. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0996-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayad S, et al. The extracellular matrix factsbook. Academic Press; 1998. p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruoslahti E. How cancer spreads. Scientific American. 1996;275(3):72–78. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0996-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thapa A, et al. Nano-structured polymers enhance bladder smooth muscle cell function. Biomaterials. 2003;24(17):2915–2926. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller DC, et al. Endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell function on poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) with nano-structured surface features. Biomaterials. 2004;25(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hufnagel H, et al. An integrated cell culture lab on a chip: modular microdevices for cultivation of mammalian cells and delivery into microfluidic microdroplets. Lab on a Chip. 2009;9(11):1576–1582. doi: 10.1039/b821695a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osborne SE, et al. Aptamers as therapeutic and diagnostic reagents: problems and prospects. Current opinion in chemical biology. 1997;1(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(97)80102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan Y, et al. Surface Immobilized Aptamers for Cancer Cell Isolation and Microscopic Cytology. Cancer research. 2010;70(22):11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seal S, Kalita SJ. Nanostructured Biomaterials. In: Lockwood DJ, editor. Functional Nanostructures. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 168–219. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JN, et al. Solvent Compatibility of Poly(dimethylsiloxane)-Based Microfluidic Devices. Analytical Chemistry. 2003;75(23):6544–6554. doi: 10.1021/ac0346712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iqbal SM, et al. Solid-state nanopore channels with DNA selectivity. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2(4):243–248. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sui G, et al. Solution-phase surface modification in intact poly (dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic channels. Analytical Chemistry. 2006;78(15):5543–5551. doi: 10.1021/ac060605z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan C-M. Polymer surface modification and characterization. Cincinnati, OH: Hanser Gardner Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Udenfriend S, et al. Fluorescamine: a reagent for assay of amino acids, peptides, proteins, and primary amines in the picomole range. Science. 1972;178:871–872. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4063.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farokhzad OC, et al. Nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates: a new approach for targeting prostate cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2004;64(21):7668–7672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nosonovsky M, Bhushan B. Biologically Inspired Surfaces: Broadening the Scope of Roughness. Advanced Functional Materials. 2008;18(6):843–855. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhushan B. Adhesion and stiction: Mechanisms, measurement techniques, and methods for reduction. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B: Microelectronics and Nanometer Structures. 2003;21:2262. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu QF, et al. Directing the transportation of a water droplet on a patterned superhydrophobic surface. Applied Physics Letters. 2008;93:233112. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattacharya S, et al. Mechanics of plasma exposed spin-on-glass (SOG) and polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS) surfaces and their impact on bond strength. Applied Surface Science. 2007;253(9):4220–4225. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharya S, et al. Plasma Modification of Polymer Surfaces and Their Utility in Building Biomedical Microdevices. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology. 2010;24(15–16):2707–2739. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hillborg H, Gedde UW. Hydrophobicity recovery of polydimethylsiloxane after exposure to corona discharges. Polymer. 1998;39(10):1991–1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharya S, et al. Studies on surface wettability of poly(dimethyl) siloxane (PDMS) and glass under oxygen-plasma treatment and correlation with bond strength. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems. 2005;14(3):590–597. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berdichevsky Y, et al. UV/ozone modification of poly (dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic channels. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2004;97(2–3):402–408. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diaz-Quijada GA, Wayner DDM. A simple approach to micropatterning and surface modification of poly (dimethylsiloxane) Langmuir. 2004;20(22):9607–9611. doi: 10.1021/la048761t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuentes M, et al. Directed covalent immobilization of aminated DNA probes on aminated plates. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):883–888. doi: 10.1021/bm0343949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohli P, et al. DNA-functionalized nanotube membranes with single-base mismatch selectivity. Science. 2004;305:984–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu YJ, et al. Effect of UV-Ozone Treatment on Poly (dimethylsiloxane) Membranes: Surface Characterization and Gas Separation Performance. Langmuir. 2009;26(6):4392–4399. doi: 10.1021/la903445x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown XQ, et al. Evaluation of polydimethylsiloxane scaffolds with physiologically-relevant elastic moduli: interplay of substrate mechanics and surface chemistry effects on vascular smooth muscle cell response. Biomaterials. 2005;26(16):3123–3129. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]