Abstract

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) has an astonishing number of ligands and functions, which enable it to contribute to embryonic development and human health. FAK can have different functions in different subcellular environments, and even in similar spatiotemporal contexts it can promote opposing effects. Recent advances in structural and cellular analysis of FAK are starting to reveal the interrelationships between the conformations, localizations, interactions and functions of FAK. This review focuses on our emerging understanding of how the structural framework of FAK mechanistically allows it to integrate manifold stimuli into environment-specific functions.

INTRODUCTION

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) has elicited great interest because it is essential in embryonic development, and has been implicated in cancer metastasis and heart disease (see [1,2]). Accumulated data on FAK show that it is a highly versatile nanomachine which can act in various subcellular contexts and react to diverse stimuli in different ways. FAK regulates cell adhesion and migration in response to chemotactic, haptotactic, and durotactic stimuli. Cell migration requires spatiotemporal regulation of cell attachment and the generation of traction forces to allow coordinated leading-edge protrusion and tail retraction. Intriguingly, FAK is implicated in all of these steps. FAK operates in lamellipodia or nuclei to promote different effects in the same environment, as it does in the assembly and disassembly of focal adhesions (FAs), or act in different environments to promote the same effect, as it does in cancer cell invasion and metastasis [1–5]. FAK regulates a plethora of cellular functions (including migration, proliferation, survival, cell–cell signaling, mechanosensing, cell cycle and gene transcription) and structures (including cell–extracellular matrix, the actin cytoskeleton and microtubules). These roles are supported by an even larger number of ligands [1,2]. Structural studies in live cells have revealed that the localizations and functions of FAK correlate with gross structural changes [6,7]. This review focuses on our emerging understanding of how the structural framework of FAK allows it to perform such an impressive number of functions.

FAK HARDWARE

The 125-kDa FAK consists of an N-terminal band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain, followed by a tyrosine kinase domain and a C-terminal focal adhesion targeting (FAT) domain. While none of these folded domains is unique to FAK, they are specifically modified in FAK resulting in a number of unique features [2,8–10]. The folded domains are connected by flexible linker regions. While the overall sequence of these linkers is specific for FAK, they contain low-specificity consensus interaction motifs that promote associations with many ligands (Figure 1).

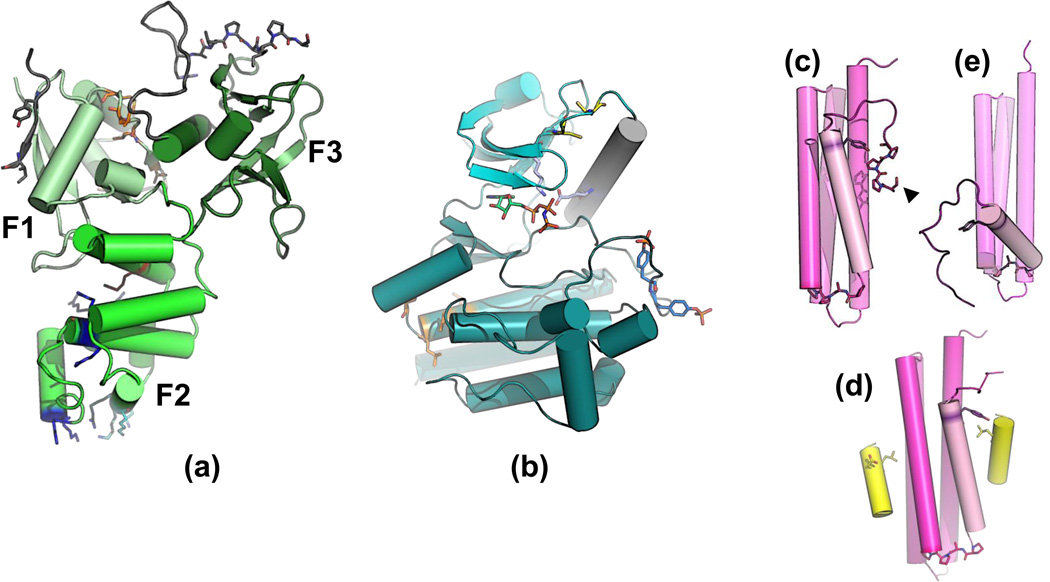

Figure 1. Structure and functional motifs on the domains of FAK.

(a) Despite a sequence identity of only 12–15 % to other FERM domains, the FAK FERM domain preserves the typical three-lobed structure (Lobe F1: residues 33–127, ubiquitin-like fold; light green. F2: residues 128–253, similar to the acyl-CoA-binding protein; green. F3: residues 254–352, pleckstrin homology fold; dark green); PDB ID 2AL6 [9]. FAK FERM mediates similar intramolecular and intermolecular interactions to other FERM domains [9,35], however in a unique way. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2) and the cytoplasmic tail of the phosphorylated hepatocyte growth-factor receptor Met interact with the K216AKTLRK sequence (magenta) of lobe F2 [6,20]. K216AKTLRK, also forms a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) together with arginines 177, 178, 204, and 205 and lysines 190, 191, and 209 (blue)[3]. A groove on F3 contributes to an auto-inhibitory conformation by binding the ~55 residue FERM-kinase linker (see Figure 2). This linker contains a proline-rich sequence (PR1) for class I interactions with Src homology (SH) 3 domains (R368ALPSIP) and a phosphotyrosine motif (Y397AEI) that interacts with SH2 domains [9,36]. The FERM–kinase linker residues visible in the crystal structure are shown in gray, with R368ALPSIP and Y397AEI highlighted [9]. The FAK FERM domain also includes a site of sumoylation on Lys152 [37] and a weak nuclear export signal (NES) on F1 (L90xxxxVxxLxLxM102; orange).

(b) A second synergistic NES (L518xLxxLxL525, orange) is located in the FAK kinase domain [38] (residues 412–686), shown here in its activated form (PDB ID 2J0L). The N-terminal lobe (light magenta) contains the Cα-helix (gray), catalytic residues Glu471 and Lys454 (light blue) and the conserved cysteines 456 and 459 (yellow) which might have a regulatory role [39]. The C-terminal lobe (dark green) contains the activation loop with (phosphorylated) tyrosines 576 and 577 (blue). An ATP analogue is shown with carbon atoms in green. The Cα-helix is in the same position in the active and inactive conformations, indicating that FAK can not be regulated by displacement of the Cα-helix [10]. In contrast to many other tyrosine kinases, FAK does not autophosphorylate its activation loop tyrosines, but Tyr397 of the FERM-kinase linker. Like many other multidomain nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases, however, the noncatalytic domains of FAK can inhibit and/or modulate its enzymatic activity through intramolecular interactions. In FAK, the unphosphorylated kinase domain can bind to the FERM domain [10] (see Figure 2).

The conformation(s) of the ~220 residue kinase-FAT linker are currently unknown. It contains two proline-rich SH3 interaction sites (PR2; residues 712–733 and PR3; residues 867–883), phosphorylatable tyrosines and serines (major sites are Tyr861, Ser722 and Ser732), and protease cleavage sites [2,33,34].

(c) The C-terminal ~140 residues of FAK form the right-handed antiparallel 4-helix bundle FAT domain [8,28]. Similar domains are found in the C-terminal regions of other proteins that localize to focal adhesions (p130Cas family, Git1 and Git2, the vinculin tail, [8,22,40]). In the absence of ligands, binding site 1/4 interacts with an N-terminal extension (residues 908–914)[8]. This extension contains a S910PPP motif (Ser910 is indicated by an arrowhead), which is phosphorylated by Erk [5,41,42]. (d) FAT contains two binding sites for paxillin LD motifs: site 1/4 formed between helices 1 and 4 and site 2/3 formed by helices 2 and 3 [22,43,44] (assembled from PDB ID 1OW7). These sites also bind the α-helical endocytosis motif of CD4 [45]. Tyr925 (lilac) within the first FAT α-helix can be phosphorylated by the Src family kinases (SFKs) Fyn and Src, and subsequently bind to the SH2 domain of Grb2 [23]. (e) Tyr925 phosphorylation and Grb2 binding require a structural transition of FAT, probably an opening-out of helix 1 [8,46,47] (PDB ID 1K04).

MODES FOR OPERATING FAK

Kinases are normally considered active when their kinase domain can phosphorylate substrates, and inactive otherwise. The situation is different for FAK. FAK is predominantly a scaffolding protein, in which kinase activity is associated with only a subset of functions. FAK-dependent kinase activity, when it is required, is performed mostly by the Src family kinases (SFKs) Src or Fyn, which are recruited and activated by a bidentate interaction between their SH2 and SH3 domains and FAK’s p-Tyr397 and PR1 motifs [11–13] (Figure 2). The trigger for this is autophosphorylation of Tyr397. Like many receptor tyrosine kinases, this first autophosphorylation step occurs in trans and hence requires intermolecular interactions between FAK molecules [14]. As the FERM–kinase fragment alone can autophosphorylate Tyr397 in cis and trans [10], residues C-terminal to the kinase appear to restrict kinase access to Tyr397 in full-length FAK by an unknown mechanism.

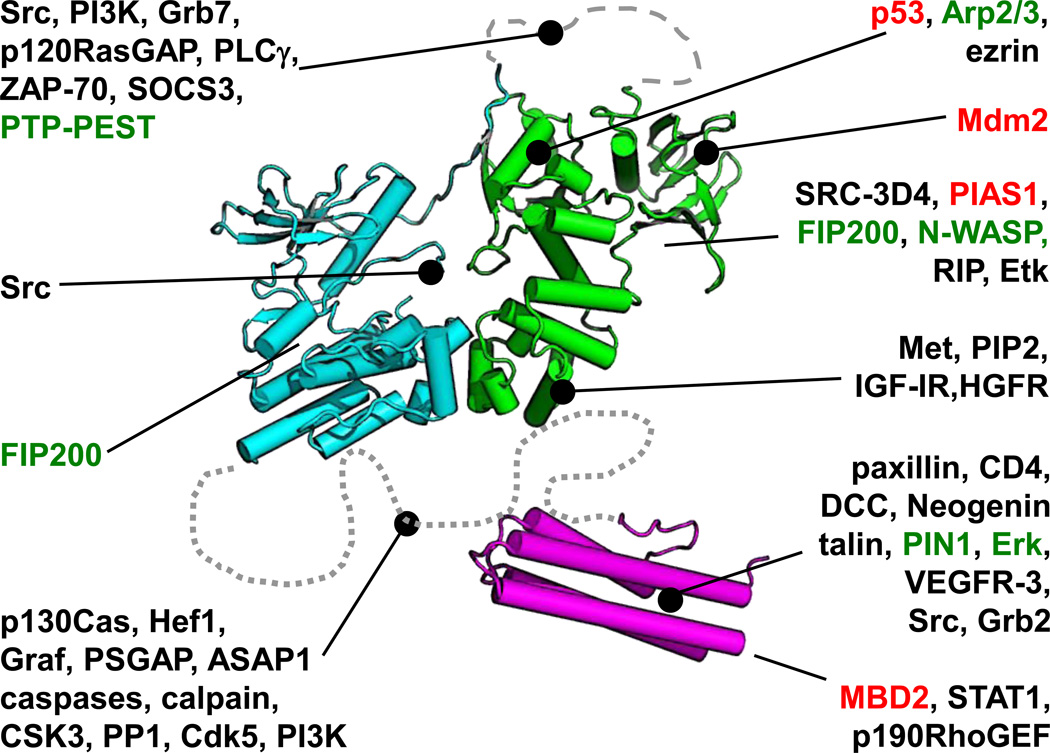

Figure 2. Structural model of full-length FAK (FERM, green; kinase, cyan; FAT, magenta).

Dashed line: FERM–kinase linker. Dotted line: kinase–FAT linker. FERM and kinase domains are shown in an auto-inhibitory conformation (PDB ID 2J0J). Selected FAK ligands are colored according to red: ligands in the nucleus; green: cytoplasmic ligands which are described as being incompatible with, or counteract FAK Tyr397 phosphorylation; black: all others. Ligands are connected to FAK domains by either a line with a big dot (meaning the binding site has been identified on this domain), or without a dot (binding site on domain is unknown). For details on ligands not mentioned in this review, please see [1,2].

FAK does not form stable homo-oligomers for transautophosphorylation in cells [14]. Thus, for FAK clustering, and hence auto-activation to occur, FAK must be significantly enriched at particular sites. High local concentrations are easier to achieve in a two-dimensional environment where FAK-recruiting molecules cluster, such as the defined juxtamembrane space into which FAK is recruited in FAs [15]. In these environments, the ordered sequence of FAK enrichment, transautophosphorylation, SFK recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation may lead to a fully open and enzymatically active SFK-FAK scaffold, in which ligand binding sites on the FERM–kinase linker, the kinase–FAT linker and FAT are accessible [6,7] (Figure 3 c–f). The open conformation is stabilized by the synergy of several events: Phosphorylation of Tyr397 and the subsequent bidentate interaction of the p-Tyr397–PR1 linker segment with the SFK SH2-SH3 domain fragment are predicted to block the inhibitory interaction between the FERM-kinase linker and the FERM domain [9]. Phosphorylation of the FAK kinase activation loop by SFKs blocks the kinase domain from docking onto the FERM domain [10] (Figure 2).

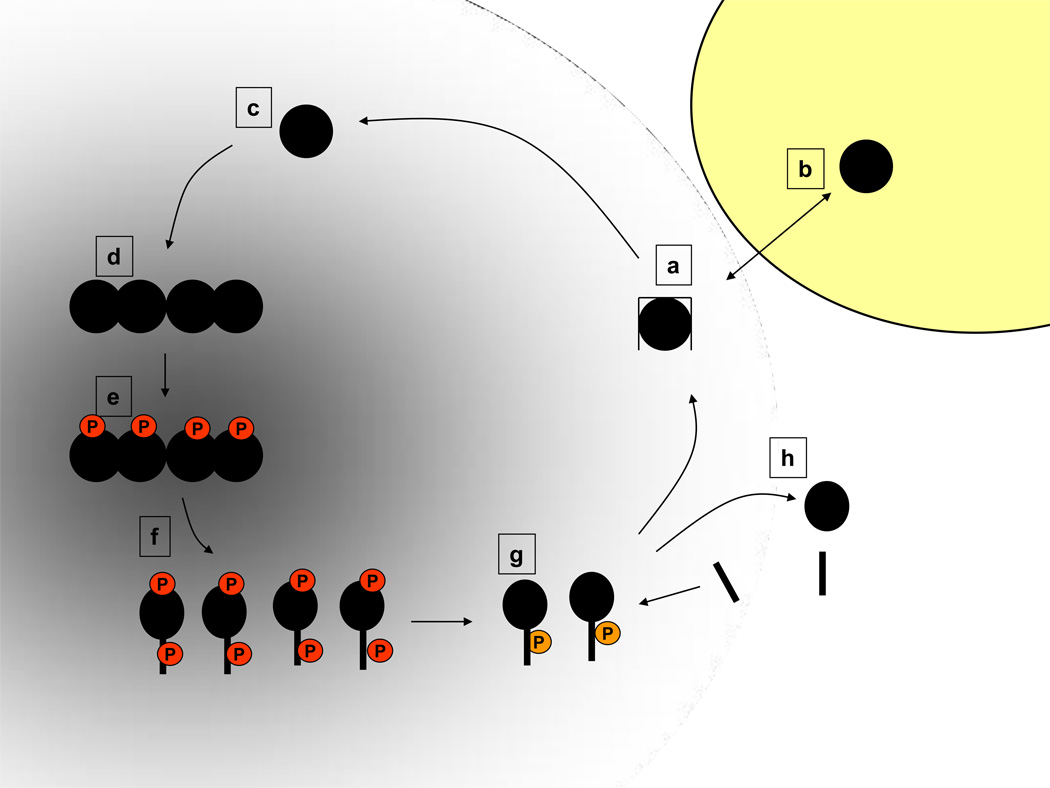

Figure 3. Examples for ligand- and localization-based decision-making in FAK function.

(a) In cells in suspension, or away from adhesions, cytoplasmic FAK is monomeric. FIP200 may prevent leaking of catalytic activity, whereas (b) ligands like MBD2 may promote FAK translocation into the nucleus (yellow) by revealing the FERM NLS or blocking FA targeting by FAT. (c) In early spreading adhesions, paxillin interacts with Nudel, rather than FAK. Monomeric and unphosphorylated FAK scaffolds N-WASP and Arp2/3 to control lamellipodia formation. (d) Enrichment of FAK in mature lamellipodia and FAs (indicated as gray shaded area) by paxillin and other FAT ligands enables FAK transautophosphorylation. (e) Interaction of additional factors (such as PIP2 or receptor tails), usually with the KAKTLRK motif, stimulates Tyr397 phosphorylation (P in red circle) in trans. (f) Phosphorylation of other FAK tyrosines (shown as one additional P in red circle) by p-Tyr397–recruited SFKs promotes a completely open FAK conformation (schematically depicted as an oval shape with stick extension) and ligand recruitment, but also initiates release from focal adhesions by weakening FAT-mediated attachment. (g) FAK Ser910 phosphorylation (P in orange circle) promotes tyrosine dephosphorylation and prolyl isomerization. The resulting down-regulation of p-Tyr397–based functions promotes disassembly and turnover of focal contacts. (h) FAK inactivation and detachment may be reinforced by proteolytic cleavage of FAK and competition by FRNK (shown as black stick).

Conversely, FAK recruitment into environments where diffusion is less restricted, or where there are no significant clusters of FAK-recruiting molecules, is expected to keep local FAK concentrations too low for activation of p-Tyr397–dependent functions. For example FAK’s anti-apoptotic function in the nucleus (where the FERM domain limits the transactivation potential of the tumor suppressor p53 and stimulates p53 degradation by physically linking it to Mdm2) is kinase-independent [3,16], and only Tyr397-dephosphorylated FAK is localized in nuclei in the hypertrophic myocardium [17]. In nascent lamellipodia at the leading edge of cells, paxillin associates with Nudel rather than with FAK [18]. This may result in local FAK concentrations being too low to allow Tyr397 transautophosphorylation, because in nascent lamellipodia FAK FERM scaffolds an association between N-WASP and Arp2/3 (leading to control of actin filament formation) which is released upon Tyr397 phosphorylation in FAs [19] (Figure 3). Thus, the control of concentration-dependent Tyr397 phosphorylation may be an important mode of decision-making for FAK.

Interestingly, an insertion of seven additional residues between Tyr397 and the kinase domain in a neuronal FAK splice forms allows intramolecular Tyr397 phosphorylation in cis. Because this insertion overrides the need for FAK clustering to promote Tyr397 phosphorylation, neuronal FAK appears to be controlled by a different regulatory network [14].

RECRUITING FAK

Recruitment of FAK to different subcellular environments results from an intricate interplay between localization motifs on FAK and intra- or intermolecular interactions. The FAT domain triggers FA-recruitment through interactions with paxillin and/or talin [2]. The FERM KAKTLRK motif is additionally required to recruit FERM to cell membranes and to promote activating conformational changes and stimulate phosphorylation of FAK [6,7]. These conformational changes, most probably characterized by a disruption of the FERM:kinase interaction, facilitate Tyr397 autophosphorylation and subsequent Src recruitment. This Tyr397-dependent FAK activation can be triggered by PIP2 binding to KAKTLRK [6]. Positive feedback mechanisms may ensue from the interaction of FAK with PIP2-generating enzymes such as PIP5KIγ and PI3K. The interaction between bisphosphorylated Met and KAKTLRK also stimulates phosphorylation and enzymatic activity of FAK [20], possibly through a mechanism similar to the one triggered by the interaction between PIP2 and KAKTLKR. It is currently unknown how PIP2 or Met binding to KAKTLRK — which is about 13 Å away from the FERM F2 subdomain :kinase interaction site — facilitates release of the FERM:kinase lock. Intriguingly, the FERM KAKTLRK motif is also part of an NLS [3]). Nuclear localization through this motif may ensue from an absence of FA-recruiting factors, or be promoted more actively by a different set of ligands; for example the methyl CpG-binding domain protein 2 (MBD2) was suggested to promote FAK nuclear translocation by binding to FAT [21]. Possibly, MBD2 could thus block FAT-promoted FA recruitment.

The FAT domain itself has several layers of regulation, partly resulting from its possession of two peptide-binding sites, known as the ¼ and 2/3 sites. To allow paxillin LD motif binding to FAT site 1/4, the association between the N-terminal tail and the 4-helix core of FAT must be disrupted [8,22] (Figure 1 c,d). In turn, the paxillin:FAT interaction has to be disrupted to allow stimulation of the Ras/MAPK signal transduction pathway [23]. Whereas paxillin binding requires FAT to adopt the 4-helix bundle conformation, Src phosphorylation of Tyr925 and subsequent Grb2 binding require an open FAT conformation [8]. Ras/MAPK signaling can therefore occur only after FAT and paxillin have dissociated. Opening of FAT is likely to be promoted by spring forces built up by the proline-rich motif P944APP between helices 1 and 2 [8,24] (Figure 1 c,e). This opening is a rare event in vitro [8], and may function as a time-switch and/or be catalyzed by unknown partners. p-Tyr925–stimulated release of FAT from paxillin may also facilitate release of FAK from focal adhesions and thus enable different FAK locations and functions [25]. Indeed, phosphorylation of Tyr925 and subsequent recruitment of Grb2 and dynamin into a complex with FAK is required for active microtubule-induced disassembly of focal adhesions [26]. Alternatively, talin and possibly other binding partners that do not require structural integrity of the FAT 4-helix bundle may maintain FAK localization after FAT is disassembled [27,28].

CHANGING GEARS

Whereas tyrosine-phosphorylation is associated with FAK-p-Tyr397–dependent ligand binding, ligand phosphorylation and signaling at FAs, serine phosphorylation correlates with inactivation of this signaling pathway and activation of a different subset of functions. Phosphorylation of FAK Ser722 [regulated by glycogen synthase 3 (GSK3) and PP1 phosphatase] inhibits FAK catalytic activity [29]. Phosphorylation of Ser732 by Cdk5 is required for cytoskeletal reorganization and centrosome function in mitosis [30]. Ser722 and Ser732 are located 35 and 45 residues downstream of the kinase domain, respectively; how their phosphorylation influences catalytic activity and function is not known. Ras-induced Erk phosphorylation of FAK Ser910 recruits the peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase PIN1 and the phosphatase PTP-PEST to FAK in lamellipodia, leading to Tyr397 dephosphorylation at these sites [5]. These events, which promote cell migration, invasion and metastasis, require p-Ser910–dependent prolyl isomerisation of FAK by PIN1[5]. Ser910 is located in the S910PPP motif of the FAT N-terminal extension that binds to FAT site 1/4 (Figure 1c). Phosphorylation of Ser910 transforms the S910PPP motif into the PIN1 substrate consensus. PIN1 may therefore regulate the interaction of S910PPP with FAT site 1/4, and thus affect binding of paxillin LD and Grb2 to FAT and stability of the FAT 4-helix bundle.

The FAK family interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200) blocks FAK-dependent phosphorylation in another way. In vitro, direct interaction between FIP200 and the FAK FERM and kinase domains inhibits FAK kinase activity by an unknown mechanism. The FIP200:FAK complex is observed in cells in suspension but dissociates upon integrin-dependent cell adhesion [31]. FIP200 could thus constitute a mechanism for avoiding untimely “leaking” of FAK enzymatic activity (Figure 3 a).

The FAK-related nonkinase (FRNK) is transcribed from a second promoter within the FAK gene and comprises the C-terminal part of FAK (including the kinase–FAT linker and FAT). FRNK acts as a physiological dominant-negative regulator by displacing FAK from focal adhesions. It has been suggested that, by doing so, FRNK suppresses excess FAK signaling in the neonatal heart [32]. Interestingly, cleavage of FAK by calpain and caspases within the kinase–FAT linker also creates FRNK-like fragments [33,34] (Figure 3 h).

CONCLUSION

A fascinating arsenal of intercalated feedback loops, alternative partners and subcellular loci governs the diverse and sometimes opposing functions of FAK. Like many other eukaryotic signaling proteins, the intact FAK protein has a multi-domain structure that is too flexible and dynamic for crystallographic analyses, too small for electron microscopy, and too large for NMR. Because of these characteristics, only the combination of techniques, including atomic-resolution, domain-resolution, and in vivo conformational studies has allowed an emerging understanding of the structure–function relationship that allows full-length FAK to process manifold stimuli. Such integrated biological approaches will certainly reveal many more intriguing details about FAK and other multi-domain proteins in the future. Knowledge thus gained will be fundamental not only to understand the versatile and heterogeneous ways in which eukaryotes use cell signaling components, but also to develop specific therapeutic agents. FAK is a highly attractive target for anti-cancer strategies, because FAK overexpression is observed in many types of cancer cells and often correlates with poor prognosis [2]. However rational design of molecular FAK inhibitors, especially those inhibiting protein–protein interactions, requires understanding of the intricate links among ligand binding, FAK localization, and FAK action.

Highlights.

-

-

Intra- and intermolecular interactions of FAK enable environment-specific functions.

-

-

FAK is a scaffolding protein, with a phosphorylation switch between actions.

-

-

Localization controls FAK enrichment, which controls FAK-dependent phosphorylation.

-

-

Serine or tyrosine phosphorylations on FAK trigger different functions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I apologize to all colleagues whose work could not be explicitly mentioned due to restrictions in space and number of references. I thank J-A. Girault, D. Arsenieva, Z. Lu and J.E. Ladbury for critical reading of this manuscript and K. Muller for editorial assistance. This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672). This research was supported by the University Cancer Foundation via the Institutional Research Grant program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schaller MD. Cellular functions of FAK kinases: insight into molecular mechanisms and novel functions. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1007–1013. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall JE, Fu W, Schaller MD. Focal Adhesion Kinase Exploring FAK Structure to Gain Insight into Function. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011;288:185–225. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386041-5.00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lim ST, Chen XL, Lim Y, Hanson DA, Vo TT, Howerton K, Larocque N, Fisher SJ, Schlaepfer DD, Ilic D. Nuclear FAK promotes cell proliferation and survival through FERM-enhanced p53 degradation. Mol Cell. 2008;29:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.031. •• This publication describes a biological role for nuclear FAK in promoting cell proliferation and survival by facilitating p53 turnover. The study reveals FAK's NLS and binding sites for p53 and Mdm2. It is shown that p53 degradation by FAK is independent of its kinase activity.

- 4. Golubovskaya VM, Conway-Dorsey K, Edmiston SN, Tse CK, Lark AA, Livasy CA, Moore D, Millikan RC, Cance WG. FAK overexpression and p53 mutations are highly correlated in human breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1735–1738. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24486. • This study provides the first demonstration for a high correlation between FAK expression and p53 mutations in a population-based series of breast tumors.

- 5. Zheng Y, Xia Y, Hawke D, Halle M, Tremblay ML, Gao X, Zhou XZ, Aldape K, Cobb MH, Xie K, et al. FAK phosphorylation by ERK primes ras-induced tyrosine dephosphorylation of FAK mediated by PIN1 and PTP-PEST. Mol Cell. 2009;35:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.013. •• This study describes the molecular basis for FAK serine phosphorylation, proline isomerization and tyrosine dephosphorylation and the importance of these events in the regulation of FAK activity and Ras-related tumor metastasis

- 6. Cai X, Lietha D, Ceccarelli DF, Karginov AV, Rajfur Z, Jacobson K, Hahn KM, Eck MJ, Schaller MD. Spatial and temporal regulation of focal adhesion kinase activity in living cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:201–214. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01324-07. •• This is the first description of the use of conformational biosensors to assess conformational regulation of FAK in living cells. PIP2 binding to the KAKTLRK motif is shown to result in activating conformational changes.

- 7. Papusheva E, Mello de Queiroz F, Dalous J, Han Y, Esposito A, Jares-Erijmanxa EA, Jovin TM, Bunt G. Dynamic conformational changes in the FERM domain of FAK are involved in focal-adhesion behavior during cell spreading and motility. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:656–666. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028738. • Using conformational biosensors this study highlights heterogenous FAK conformations: in FAs shows the importance of the KAKTLRK motif for promoting structural rearrangements.

- 8.Arold ST, Hoellerer MK, Noble ME. The structural basis of localization and signaling by the focal adhesion targeting domain. Structure. 2002;10:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceccarelli DF, Song HK, Poy F, Schaller MD, Eck MJ. Crystal structure of the FERM domain of focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:252–259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lietha D, Cai X, Ceccarelli DF, Li Y, Schaller MD, Eck MJ. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of focal adhesion kinase. Cell. 2007;129:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.041. •• Crystal structures and other experiments show how an intramolecular interaction between the FERM and kinase domains controls FAK enzymatic activity.

- 11.Schaller MD, Hildebrand JD, Shannon JD, Fox JW, Vines RR, Parsons JT. Autophosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK, directs SH2-dependent binding of pp60src. Mol.Cell.Biol. 1994;14:1680–1688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas JW, Ellis B, Boerner RJ, Knight WB, White GC, II, Schaller MD. SH2- and SH3-mediated interactions between focal adhesion kinase and Src. J.Biol.Chem. 1998;273:577–583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arold ST, Ulmer TS, Mulhern TD, Werner JM, Ladbury JE, Campbell ID, Noble ME. The role of the Src homology 3-Src homology 2 interface in the regulation of Src kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17199–17205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toutant M, Costa A, Studler JM, Kadare G, Carnaud M, Girault JA. Alternative splicing controls the mechanisms of FAK autophosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7731–7743. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7731-7743.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanchanawong P, Shtengel G, Pasapera AM, Ramko EB, Davidson MW, Hess HF, Waterman CM. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature. 2010;468:580–584. doi: 10.1038/nature09621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golubovskaya VM, Finch R, Cance WG. Direct interaction of the N-terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase with the N-terminal transactivation domain of p53. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25008–25021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi XP, Wang X, Gerdes AM, Li F. Subcellular redistribution of focal adhesion kinase and its related nonkinase in hypertrophic myocardium. Hypertension. 2003;41:1317–1323. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000072772.74183.5F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shan Y, Yu L, Li Y, Pan Y, Zhang Q, Wang F, Chen J, Zhu X. Nudel and FAK as antagonizing strength modulators of nascent adhesions through paxillin. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serrels B, Serrels A, Brunton VG, Holt M, McLean GW, Gray CH, Jones GE, Frame MC. Focal adhesion kinase controls actin assembly via a FERM-mediated interaction with the Arp2/3 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1046–1056. doi: 10.1038/ncb1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SY, Chen HC. Direct interaction of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) with Met is required for FAK to promote hepatocyte growth factor-induced cell invasion. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5155–5167. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02186-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo SW, Zhang C, Zhang B, Kim CH, Qiu YZ, Du QS, Mei L, Xiong WC. Regulation of heterochromatin remodelling and myogenin expression during muscle differentiation by FAK interaction with MBD2. EMBO J. 2009;28:2568–2582. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.178. • This is the first description of MBD2's role in promoting nuclear localization of FAK and regulation of chromatin remodeling by FAK.

- 22.Hoellerer MK, Noble ME, Labesse G, Campbell ID, Werner JM, Arold ST. Molecular recognition of paxillin LD motifs by the focal adhesion targeting domain. Structure. 2003;11:1207–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlaepfer DD, Hanks SK, Hunter T, van der Geer P. Integrin-mediated signal transduction linked to Ras pathway by GRB2 binding to focal adhesion kinase. Nature. 1994;372:786–791. doi: 10.1038/372786a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourne Y, Arvai AS, Bernstein SL, Watson MH, Reed SI, Endicott JE, Noble ME, Johnson LN, Tainer JA. Crystal structure of the cell cycle-regulatory protein suc1 reveals a beta-hinge conformational switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10232–10236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz BZ, Romer L, Miyamoto S, Volberg T, Matsumoto K, Cukierman E, Geiger B, Yamada KM. Targeting membrane-localized focal adhesion kinase to focal adhesions: roles of tyrosine phosphorylation and SRC family kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29115–29120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ezratty EJ, Partridge MA, Gundersen GG. Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly is mediated by dynamin and focal adhesion kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:581–590. doi: 10.1038/ncb1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen HC, Appeddu PA, Parsons JT, Hildebrand JD, Schaller MD, Guan JL. Interaction of focal adhesion kinase with cytoskeletal protein talin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16995–16999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayashi I, Vuori K, Liddington RC. The focal adhesion targeting (FAT) region of focal adhesion kinase is a four-helix bundle that binds paxillin. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nsb755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bianchi M, De Lucchini S, Marin O, Turner DL, Hanks SK, Villa-Moruzzi E. Regulation of FAK Ser-722 phosphorylation and kinase activity by GSK3 and PP1 during cell spreading and migration. Biochem J. 2005;391:359–370. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park AY, Shen TL, Chien S, Guan JL. Role of focal adhesion kinase Ser-732 phosphorylation in centrosome function during mitosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9418–9425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809040200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbi S, Ueda H, Zheng C, Cooper LA, Zhao J, Christopher R, Guan JL. Regulation of focal adhesion kinase by a novel protein inhibitor FIP200. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3178–3191. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DiMichele LA, Hakim ZS, Sayers RL, Rojas M, Schwartz RJ, Mack CP, Taylor JM. Transient expression of FRNK reveals stage-specific requirement for focal adhesion kinase activity in cardiac growth. Circ Res. 2009;104:1201–1208. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.195941. • This study describes the role of FRNK for regulating FAK activity in cardiac growth.

- 33.Wen LP, Fahrni JA, Troie S, Guan JL, Orth K, Rosen GD. Cleavage of focal adhesion kinase by caspases during apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26056–26061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.26056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan KT, Bennin DA, Huttenlocher A. Regulation of adhesion dynamics by calpain-mediated proteolysis of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11418–11426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090746. • This study describes how calpain cleavage of FAK regulates adhesion dynamics in motile cells.

- 35.Girault JA, Labesse G, Mornon JP, Callebaut I. The N-termini of FAK and JAKs contain divergent band 4.1 domains. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:54–57. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lietha D, Eck MJ. Crystal structures of the FAK kinase in complex with TAE226 and related bis-anilino pyrimidine inhibitors reveal a helical DFG conformation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadare G, Toutant M, Formstecher E, Corvol JC, Carnaud M, Boutterin MC, Girault JA. PIAS1-mediated sumoylation of focal adhesion kinase activates its autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47434–47440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ossovskaya V, Lim ST, Ota N, Schlaepfer DD, Ilic D. FAK nuclear export signal sequences. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2402–2406. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nowakowski J, Cronin CN, McRee DE, Knuth MW, Nelson CG, Pavletich NP, Rogers J, Sang BC, Scheibe DN, Swanson RV, et al. Structures of the cancer-related Aurora-A, FAK, EphA2 protein kinases from nanovolume crystallography. Structure. 2002;10:1659–1667. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmalzigaug R, Garron ML, Roseman JT, Xing Y, Davidson CE, Arold ST, Premont RT. GIT1 utilizes a focal adhesion targeting-homology domain to bind paxillin. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1733–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunger-Glaser I, Salazar EP, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Bombesin, lysophosphatidic acid, and epidermal growth factor rapidly stimulate focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation at Ser-910: requirement for ERK activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22631–22643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunger-Glaser I, Fan RS, Perez-Salazar E, Rozengurt E. PDGF and FGF induce focal adhesion kinase (FAK) phosphorylation at Ser-910: dissociation from Tyr-397 phosphorylation and requirement for ERK activation. J Cell Physiol. 2004;200:213–222. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao G, Prutzman KC, King ML, Scheswohl DM, DeRose EF, London RE, Schaller MD, Campbell SL. NMR solution structure of the focal adhesion targeting domain of focal adhesion kinase in complex with a paxillin LD peptide: evidence for a two-site binding model. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8441–8451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309808200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bertolucci CM, Guibao CD, Zheng J. Structural features of the focal adhesion kinase-paxillin complex give insight into the dynamics of focal adhesion assembly. Protein Sci. 2005;14:644–652. doi: 10.1110/ps.041107205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garron ML, Arthos J, Guichou JF, McNally J, Cicala C, Arold ST. Structural basis for the interaction between focal adhesion kinase and CD4. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon RD, Chen Y, Ding F, Khare SD, Prutzman KC, Schaller MD, Campbell SL, Dokholyan NV. New insights into FAK signaling and localization based on detection of a FAT domain folding intermediate. Structure. 2004;12:2161–2171. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Z, Feng H, Bai Y. Detection of a hidden folding intermediate in the focal adhesion target domain: Implications for its function and folding. Proteins. 2006;65:259–265. doi: 10.1002/prot.21107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]