Abstract

Social norms theories hold that perceptions of the degree of approval for a behavior have a strong influence on one’s private attitudes and public behavior. In particular, being more approving of drinking and perceiving peers as more approving of drinking, are strongly associated with one’s own drinking. However, previous research has not considered that students may vary considerably in the confidence in their estimates of peer approval and in the confidence in their estimates of their own approval of drinking. The present research was designed to evaluate confidence as a moderator of associations among perceived injunctive norms, own attitudes, and drinking. We expected perceived injunctive norms and own attitudes would be more strongly associated with drinking among students who felt more confident in their estimates of peer approval and own attitudes. We were also interested in whether this might differ by gender. Injunctive norms and self-reported alcohol consumption were measured in a sample of 708 college students. Findings from negative binomial regression analyses supported moderation hypotheses for confidence and perceived injunction norms but not for personal attitudes. Thus, perceived injunctive norms were more strongly associated with own drinking among students who felt more confident in their estimates of friends’ approval of drinking. A three-way interaction further revealed that this was primarily true among women. Implications for norms and peer influence theories as well as interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Attitude certainty, injunctive norms, alcohol, college students

The Influence of Confidence on Associations Among Personal Attitudes, Perceived Injunctive Norms, and Alcohol Consumption

Research has emphasized the strong influence of social norms on private attitudes and public behavior. The application of social norms theories to health risk behaviors (for example, alcohol use) has tended to emphasize descriptive norms (perceptions of the prevalence of a behavior) versus injunctive norms (perceptions of the degree of group approval for a behavior or attitude). Moreover, limited consideration has been given to the extent to which the social norms – health behavior link may depend on the degree of confidence attributed to one’s own attitudes and perceptions of others’ attitudes. The present research evaluates confidence as a moderator of the associations between one’s own attitudes and drinking and between perceptions of others’ attitudes (perceived injunctive norms) and drinking among male and female college students.

Social norms

The operationalization of social norms began with relatively vague descriptions of general customs, traditions, and values (Sherif, 1936). It has evolved to more precise categorizations, with Cialdini and colleagues making an important distinction between descriptive and injunctive norms (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990). Descriptive norms and perceived descriptive norms refer to the actual and perceived quantity of others’ behavior, respectively. In contrast, actual and perceived injunctive norms, the primary focus of the present research, refer to the actual and perceived degree of approval that others have about a behavior. Injunctive norms are critical elements in the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior (there referred to as subjective norms; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Armitage & Conner, 2001; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975, 2010).

According to the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Armitage & Conner, 2001; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975, 2010), how one intends to behave is a direct function of individuals’ own evaluations or attitudes about the behavior (e.g., approval or disapproval) and their perceptions of the degree to which others’ approve or disapprove of the behavior. We propose that the degree of confidence that individuals have – whether about their own evaluations of a behavior or whether about their perceptions of the approval of important others – may moderate the influences of attitudes and injunctive norms on behavior.

Social norms and drinking

Social norms have been found to be a strong predictor of alcohol consumption among college students (Borsari & Carey, 2001; 2003; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007; Prentice & Miller, 1993). Although students drink frequently, they tend to overestimate the prevalence and approval of drinking among their peers and the magnitude of discrepancy is associated with heavier drinking (Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991; Borsari & Carey, 2003; Neighbors, Dillard, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Neil, 2006; Perkins & Berkowitz, 1986). No research to date, of which we are aware, has evaluated confidence in one’s perceptions of norms as a moderator of the association between perceived norms and drinking.

Confidence

The absence of research considering confidence as a moderator of injunctive norms motivated the present study. This was based on the observation that extensive research has documented large inconsistencies in perceptions of drinking norms and actual drinking behavior. Previous research has not examined how accurate students think they are when they provide these estimates and it stands to reason that if they feel they are just guessing, then these perceptions should have relatively little impact on their own drinking. Alternatively, if students believe they are relatively accurate in their perceptions of peer approval, then it would stand to reason that their estimates should have considerably more influence on their behavior.

Although confidence related to norms has not received much empirical attention, confidence related to attitudes has been extensively studied. Attitude confidence refers to one’s sense of conviction about (or confidence in) an attitude and is thought to represent one aspect of attitude strength (Tormala & Rucker, 2007). Stronger attitudes have a greater impact on information processing and in guiding behavior, and are more resistant to change over time (Krosnick & Petty, 1995). Attitudes held with high confidence have a substantially stronger average attitude-behavior correlation compared to attitudes held with low confidence (Kraus, 1995). With respect to drinking, we would expect that the more confident one is in his or her attitude about alcohol, the more strongly that attitude will be associated with drinking.

In theory, when one feels more confident in one’s estimate of others’ approval of a behavior, that perception should more strongly predict how often one engages in that behavior. Several studies have found confidence in one’s attitude to be associated with greater attitude – behavior correspondence (Berger & Mitchell, 1989; Fazio & Zanna, 1978; Tormala, Clarkson, & Petty, 2006; Tormala & Petty, 2002) but this effect has not been previously examined in the context of drinking.

Gender and drinking

Gender has also been found to be an important factor in considering alcohol consumption and social norms regarding alcohol use. Research has shown that male college students tend to consume larger quantities, drink more frequently, and more often engage in heavy drinking than female college students (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2008; O'Malley & Johnston, 2002; Read, Wood, Lejuez, Palfai, & Slack, 2004). Gender differences in drinking are also intertwined with gender differences in social norms for drinking. Men and women evaluate the effects of alcohol differently (Neighbors, Walker, & Larimer, 2003), and heavy drinking is more consistent with college student identity for men in comparison to women (Lyons & Willot, 2008; Prentice & Miller, 1993). In addition the social consequences of excessive drinking among college students tend to be more positive for men and more negative for women (George, Gournic, & McAfee, 1988; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

What is less clear is whether confidence in perceived approval might have differential effects on the association between perceived injunctive norms and drinking among men and women. On the one hand, we might expect that the confidence – injunctive norm interaction might be more evident among men than women, given that drinking norms tend to be more salient for men (e.g., Prentice & Miller, 1993). On the other hand, previous research suggests that moderators of normative influences on drinking behavior tend to be less evident in the presence of stronger drinking norms. For example, Knee and Neighbors (2002) found that peer influence was moderated by individual differences in self-determination among typical male and female students, but not among fraternity students, where the heavier drinking norm may overshadow individual differences. We were also interested in evaluating whether confidence in one’s attitudes might influence the attitude – behavior association differently for women than for men.

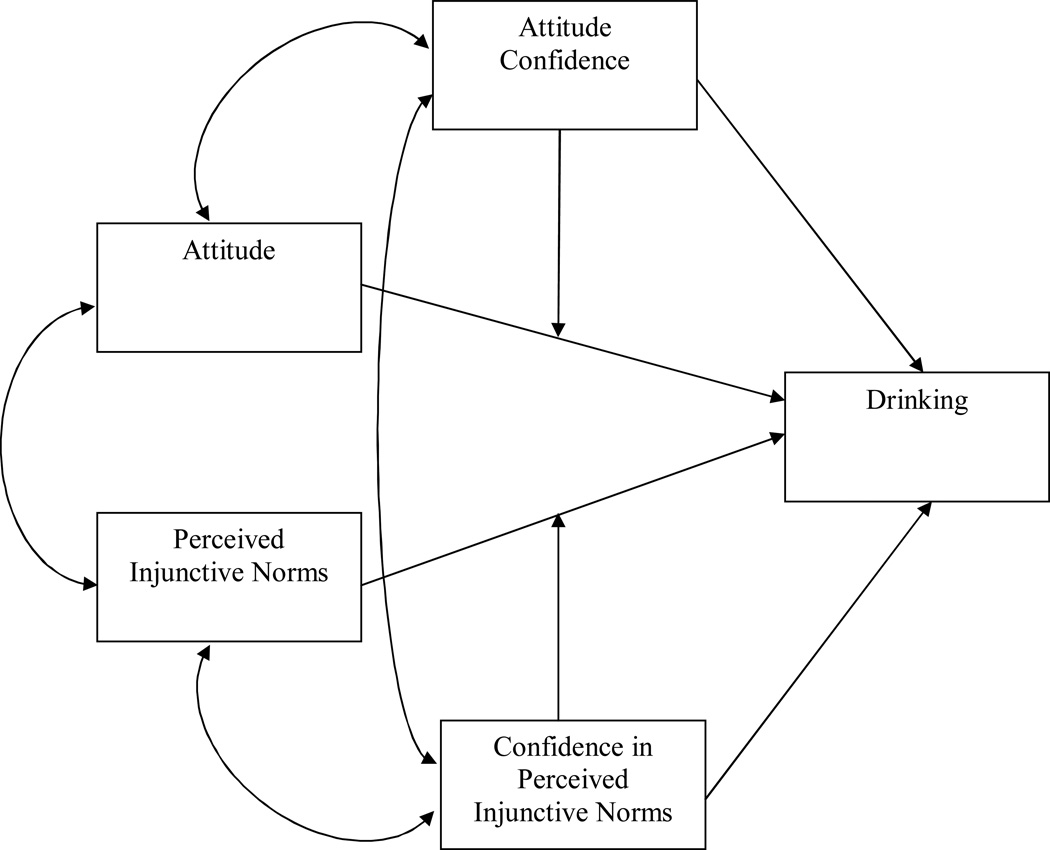

The present research was designed to evaluate confidence as a moderator of associations among perceived injunctive norms, own attitudes, and drinking. We expected perceived injunctive norms and own attitudes would be more strongly associated with drinking among students who felt more confident in their estimates of peer approval and own attitudes. We also tested whether these associations varied by gender. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model representing the hypotheses.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Evaluated interactions are represented by pathways from a variable to a pathway. Thus, the arrow from attitude confidence to the arrow from attitude to drinking represents the prediction that attitude confidence would moderate the association between attitude and drinking. Gender was also evaluated as a moderator of associations between variables and drinking and as a moderator of two-way interactions.

Method

Participants

Participants were 708 (60.1% women) undergraduates at a large public university who took part in a longitudinal web-based alcohol intervention study. Participants who met heavy drinking criteria (at least 4/5 drinks on at least one occasion over the previous month for women/men) completed a baseline survey in the Fall of 2005. The present study comes from the 12 month follow-up survey. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 28 (M = 19.12; SD = .57). Ethnicity was 65.6% white, 23.5% Asian, and 10.9% classified as other. The majority (86.7%) of the sample were of sophomore class standing at the time of the 12 month follow-up survey.

Procedure

First-year university students were invited to complete a screening survey (N = 4,103). Of those invited, 2,095 (51.1%) participants provided informed consent and completed screening. Students meeting the heavy drinking inclusion criteria (N = 896; 42.7%) were immediately routed to the baseline survey. Of the participants who met study criteria, 818 (91.3%) completed the baseline survey. Participants were contacted via mailed letters, email, and phone calls to complete online surveys at 6 month intervals over a two-year follow-up period. Data for the current study come from the 12 month follow-up survey (86.6% retention rate). The assessment took approximately 50 minutes to complete and participants were compensated $25. The University’s Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of the current study.

Measures

Attitudes

Participants’ attitudes toward drinking were measured using items developed by Baer (1994). Participants responded to 4 items assessing their approval of four drinking behaviors: drinking alcohol every weekend, drinking alcohol daily, driving a car after drinking, and drinking enough alcohol to pass out (e.g., “How much do you approve of drinking alcohol daily?”). The response scale ranged from 1 = Strong disapproval to 7 = Strong approval. The items were averaged to create one variable of participants’ own approval of risky alcohol use (α= .72.

Perceived injunctive norms

Perceived injunctive norms were measured using the same 4 items used to measure participants own approval of risky alcohol use, but were revised to ask about participants’ perceptions of their friends’ approval of their alcohol use (e.g., “How would your friends feel if you drank alcohol daily”). The response scale ranged from 1 = Strong disapproval to 7 = Strong approval. The items were averaged to create one variable of participants’ perceived injunctive norms for risky alcohol use (α= .76).

Confidence

was measured by asking participants to rate their confidence in estimates of one’s own approval and friends’ approval of drinking. Following the set of items asking about participants’ own approval and the set of items asking about perceived injunctive norms, participants were asked to: “Please indicate how confident you are that your responses to the previous items are correct.” Response scales ranged from 1 = Not at all Confident to 7 = Absolutely Confident.

Alcohol consumption

Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) was used to measure quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption. Participants were asked to "Consider a typical week during the last three months. How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), do you drink on each day of a typical week?" Responses consisted of the typical number of drinks participants reported consuming on each day of the week. A weekly drinking variable was calculated by summing responses for each day of the week. The DDQ has demonstrated convergent validity with measures of drinking and good test-retest reliability (Baer et al., 1991; Borsari and Carey, 2000; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004; Neighbors et al., 2006).

Results

Hypotheses were tested with hierarchical negative binomial regression (Cohen, Cohen, West, Aiken, 2003; Hilbe, 2007), an approach that is comparable to hierarchical linear regression with the exception that the outcome follows a negative binomial distribution. Means and standard deviations by gender are presented in Table 1. Zero-order correlations for study measures are presented by gender in Table 2 for descriptive purposes. Drinks per week, a count variable, was specified as the outcome variable. Count variables consist of non-negative integers, which tend to be positively skewed, and are better approximated by a Poisson or negative binomial distribution rather than a normal distribution (Atkins & Gallop, 2007). Analyses were conducted hierarchically with order of entry following priority of theoretical interest. Gender was dummy coded (Men = 1) and centered. All other predictors were mean centered.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations by gender

| Variable | Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | t | |

| Drinks per Week | 283 | 13.94 | 14.43 | 425 | 8.32 | 7.74 | 6.71*** |

| Own Approval | 281 | 2.65 | 0.97 | 423 | 2.33 | 0.78 | 4.67*** |

| Confidence in Own Approval | 277 | 6.30 | 1.04 | 421 | 6.18 | 1.17 | 1.31 |

| Perceived Inj. Norms | 281 | 2.87 | 1.10 | 423 | 2.45 | 0.94 | 5.36*** |

| Confidence in Perceived Inj. Norms | 276 | 5.80 | 1.09 | 422 | 5.72 | 1.20 | 0.87 |

Note.

p < .001.

Perceived Inj. Norms = Perceived Injunctive Norms.

Table 2.

Zero-order Correlations among Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Own Approval | -- | −0.14** | 0.66*** | −0.15** | 0.38*** |

| 2. Confidence in Own Approval | −0.21*** | -- | −0.11* | 0.48*** | −0.14** |

| 3. Perceived Inj. Norms | 0.69*** | −0.07 | -- | −0.17*** | 0.32*** |

| 4. Confidence in Perceived Inj. Norms | −0.10 | 0.31*** | −0.03 | -- | −0.07 |

| 5. Drinks per Week | 0.45*** | −0.08 | 0.41*** | 0.07 | -- |

Note. Correlations for women are above the diagonal. Correlations for men are below the diagonal. N’s for women ranged from 419 to 425 and N’s for men ranged from 276 to 283 depending on missing responses.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Perceived Inj. Norms = Perceived Injunctive Norms.

Main effects were entered at step 1 (gender, own approval, confidence in own approval, perceived injunctive norms, and confidence in perceived injunctive norms). Raw and exponentiated parameter estimates with significance tests and confidence intervals are presented in Table 3. Raw parameter estimates are log based. The exponentiated intercept value represents the predicted number of drinks per week for women at average values of one’s own approval and confidence in one’s own approval (8.31 drinks per week). Exponentiated parameter estimates can be interpreted as rate ratios. Thus, at step 1, the exponentiated parameter estimate for gender is 1.37, indicating that men, on average, consumed 37% more drinks per week than women (11.31 drinks per week). In addition, each unit increase in one’s own approval toward drinking was associated with consuming an average of 39% more drinks per week. Confidence in one’s own approval was marginally associated with less drinking, by 6% per unit increase. Each unit increase in perceived injunctive norms was associated with 16% more drinks per week. Confidence in perceived injunctive norms was not significantly associated with drinking.

Table 3.

Drinking as a function of gender, one’s own approval, confidence in one’s own approval, perceived injunctive norms, and confidence in perceived injunctive norms

| Variable | B | SE B | T | e ^ B | Low 95% e ^ B |

Low 95% e ^ B |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Intercept | 2.238 | 0.033 | 68.12*** | 9.375 | 8.791 | 9.999 |

| Gender | 0.317 | 0.069 | 4.59*** | 1.372 | 1.199 | 1.571 | |

| Own Approval | 0.331 | 0.057 | 5.77*** | 1.393 | 1.244 | 1.558 | |

| Confidence in Own Approval | −0.062 | 0.033 | −1.89† | 0.940 | 0.881 | 1.002 | |

| Perceived Inj. Norms | 0.150 | 0.049 | 3.09** | 1.162 | 1.057 | 1.278 | |

| Confidence in Perceived Inj. Norms | 0.029 | 0.032 | 0.91 | 1.029 | 0.967 | 1.095 | |

| Step 2 | Own Approval X Confidence in Own Approval | 0.016 | 0.036 | 0.46 | 1.016 | 0.948 | 1.090 |

| Perceived Inj. Norms X Confidence in Perceived Inj. Norms | 0.063 | 0.031 | 2.05* | 1.065 | 1.003 | 1.131 | |

| Step 3 | Gender X Own Approval | 0.045 | 0.117 | 0.39 | 1.046 | 0.832 | 1.316 |

| Gender X Confidence in Own Approval | 0.040 | 0.072 | 0.55 | 1.040 | 0.903 | 1.199 | |

| Gender X Perceived Inj. Norms | 0.040 | 0.099 | 0.40 | 1.041 | 0.857 | 1.263 | |

| Gender X Confidence in Perceived Inj. Norms | 0.111 | 0.066 | 1.68† | 1.117 | 0.982 | 1.271 | |

| Step 4 | Gender X Own Approval X Confidence in Own Approval | −0.032 | 0.078 | −0.41 | 0.968 | 0.830 | 1.129 |

| Gender X Perceived Inj. Norms X Confidence in Perceived Inj. Norms | −0.128 | 0.062 | −2.06* | 0.880 | 0.779 | 0.994 |

Note. Parameter estimates are provided for each predictor at the step at which they were first entered.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10.

Perceived Inj. Norms = Perceived Injunctive Norms.

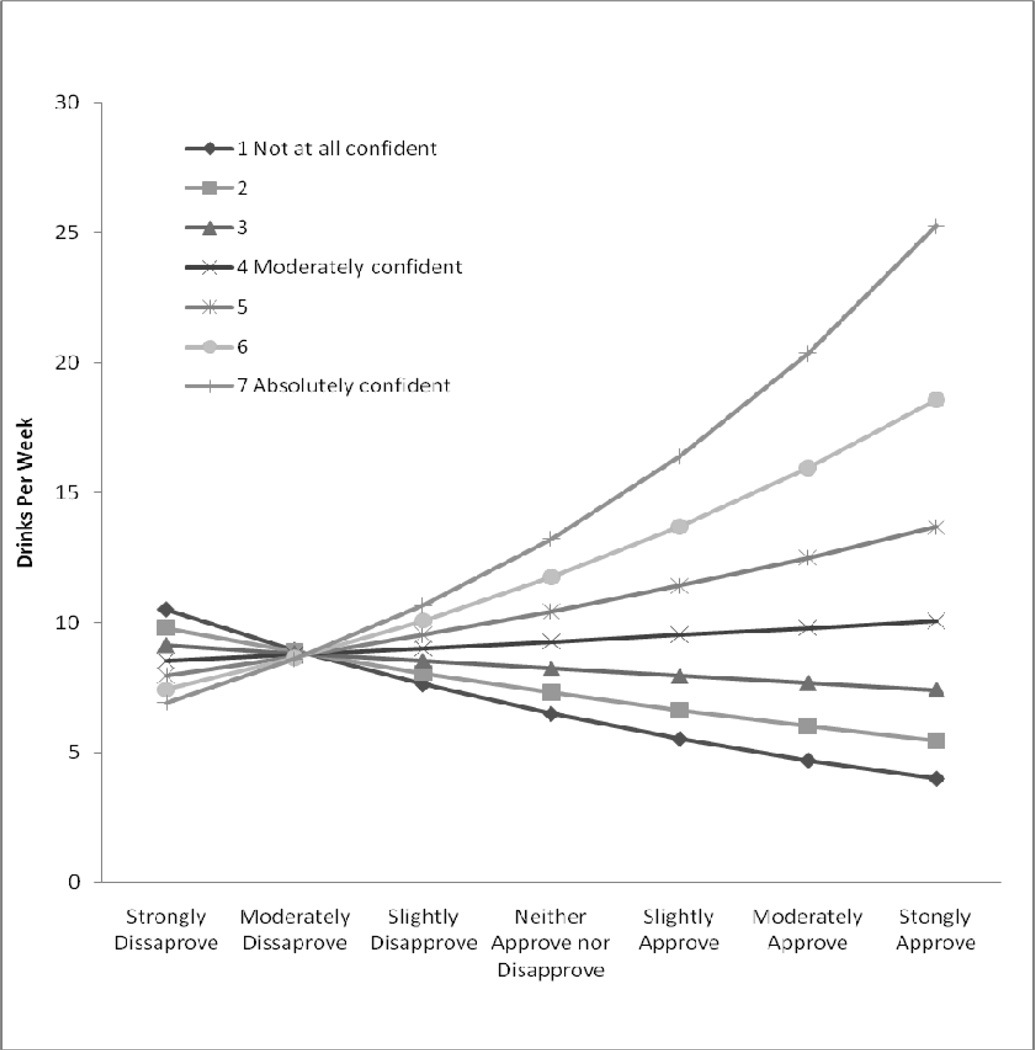

Two-way products evaluating confidence as a moderator were added at step 2 (own approval X confidence in own approval and perceived injunctive norms X confidence in perceived injunctive norms). Results indicated a significant interaction which was consistent with hypotheses. Specifically, the association between perceived injunctive norms and drinking depended on confidence in perceived injunctive norms, suggesting that the association between perceived injunctive norms and drinking increased by 6.5% for each unit increase in confidence (See Figure 2). Two-way products with gender were added at step 3. There were no significant interactions between one’s own approval and confidence in one’s own approval, nor were there any significant two-way interactions with gender at step 3.

Figure 2. Drinking as a function of perceived injunctive norms and confidence in perceived injunctive norms for friends.

Two-way interaction between confidence in percieved injunctive norms and percieived injunctive norms in predicting drinks per week. Estimates were derived from exponentiated parameter estimates were values for confidence and perceived injunctive norms were systematically subtituted in the negative binomial regression equation.

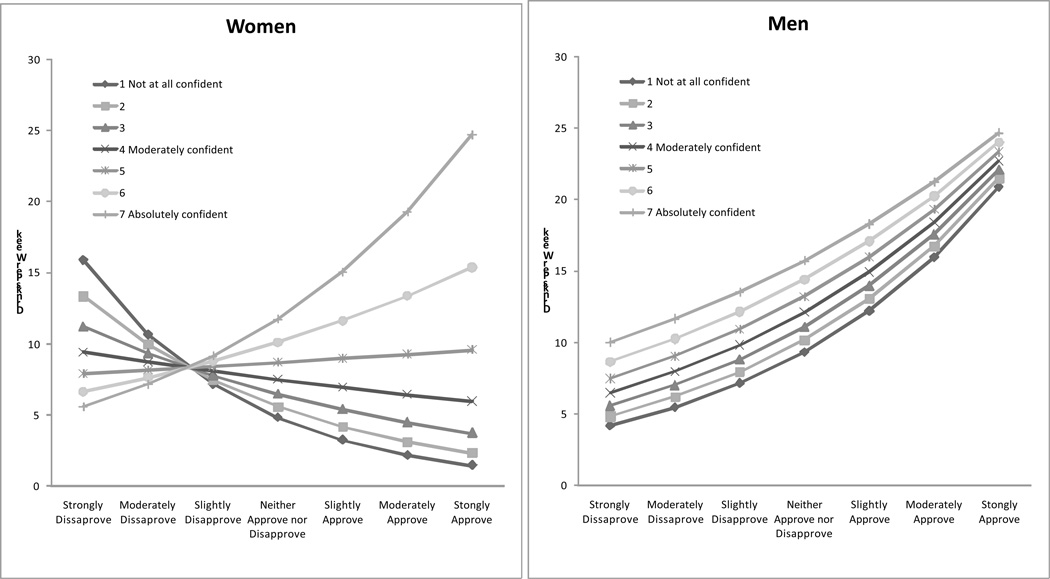

Three-way interactions to evaluate gender as a moderator of interactions between confidence and corresponding approval were added at step 4 (gender X own approval X confidence in own approval and gender X perceived injunctive norms X confidence in perceived injunctive norms). Results revealed a significant three-way interaction with gender, perceived injunctive norms, and confidence in perceived injunctive norms (Figure 3). This three-way interaction qualified the two-way interaction between perceived injunctive norms and confidence in perceived injunctive norms identified in step 2. Furthermore, tests of simple two-way interactions confirmed that confidence moderated the association between perceived injunctive norms and drinking among women, t (689) = 2.68, p < .01, but not men, t (689) = −.42, p = .68.

Figure 2. Drinking as a function of gender, perceived injunctive norms, and confidence in perceived injunctive norms for friends.

Three-way interaction among gender, confidence in percieved injunctive norms, and percieived injunctive norms in predicting drinks per week. Estimates were derived from exponentiated parameter estimates were values for gender, confidence, and perceived injunctive norms were systematically subtituted in the negative binomial regression equation.

Discussion

Injunctive norms were found to be significant, unique predictors of drinking. The present study also extended social norms research and theory by incorporating a construct from the attitude literature – e.g., attitude confidence – and investigating it as a potential moderator of the norms – behavior link. Study findings did not support confidence as a moderator of personal approval and drinking behavior but did support confidence as a moderator of the relationship between perceptions of others’ approval (injunctive norms) and behavior.

This research provides evidence that estimates of friends’ approval of drinking are more strongly associated with own drinking when students feel confident in their estimates. Furthermore, the present findings suggest that confidence in perceived injunctive norms matters more for women. This may reflect an underlying gender difference in the weighing of confidence in perceptions of others’ approval. It may, alternatively, vary as a function of the gender specificity of the behavior in question. For example, an opposite pattern of results might be found with thinness norms, which are more salient among women than men (Bergstrom & Neighbors, 2006; Sanderson, Darley, & Messinger, 2002). More generally, the self-relevance of the norm may provide a limiting condition under which confidence in perceptions of others’ approval becomes important.

The present research extends previous work indicating that attitude confidence is associated with stronger attitude – behavior relationships (Berger & Mitchell, 1989; Fazio & Zanna, 1978; Tormala et al., 2006; Tormala & Petty, 2002). Findings suggest that confidence may not be universally important in considering attitude – behavior relationships. Indeed, confidence may have a greater impact on attitudes or cognitions that are more ambivalent or in which there is greater subjectivity (e.g., perceptions of others’ approval).

The present study also has direct implications for clinical assessment and intervention. Research over the last decade has consistently found support for the importance of social norms, particularly descriptive norms, in predicting college student drinking behaviors (Borsari & Cary, 2003; Lewis & Neighbors, 2004; Neighbors et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2004). This study’s findings are consistent with previous studies as they indicate the importance and reliability of norms as a predictor of drinking. Future clinical research may benefit from considering injunctive norms as additional targets for assessment and ultimately, intervention. Findings that confidence and gender moderated the norms – drinking relationship also suggest the potential utility of assessing confidence in norms; attempting to reduce confidence (increase uncertainty) in those norms; and developing gender-specific interventions.

It is important to consider this research in light of several limitations. First, it is a single study. Multiple studies will ultimately be needed to evaluate and clarify the extent to which confidence in attitudes and perceived norms for drinking influence subsequent behavior. Second, the measures of attitudes and injunctive norms include a diverse set of target behaviors, which may increase generalizability at the cost of reducing predictive utility for specific behaviors. Additionally, the measure of attitude confidence (e.g., “Please indicate how confident you are that your responses to the previous items are correct”) could have been misinterpreted by some students. Participants may not have been sure whether this referred to confidence in the actual belief versus the accuracy of their response. Future research should clarify the instruction set. Another limitation is that the drinking measure is limited to self-report. The sample used in the present study may also limit generalizeability. All participants were college students and had to meet heavy drinking criteria in order to screen into the study. Thus, the present results may not generalize to abstainers or light drinkers or beyond the college population.

Finally, several future research directions are suggested. The present research focused exclusively on injunctive norms, and it also would be worthwhile to evaluate confidence in the context of descriptive norms. Considering other addictive behaviors, especially those that vary in relevance by gender may also be useful. Finally, experimental manipulations of confidence are needed to provide evidence of causality. In sum, the present research provides both applied and theoretical contributions to the existing literature related to attitudes, norms, and drinking.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01AA014576 and R00AA017669.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/adb.

References

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger IE, Mitchell AA. The effect of advertising on attitude accessibility, attitude confidence, and the attitude-behavior relationship. The Journal of Consumer Research. 1989;16:269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom RL, Neighbors C. Body image disturbance and the social norms approach: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:975–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: a review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct - recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3 ed. Mahwah,NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio R, Zanna M. Attitudinal qualities relating to the strength of the attitude-behavior relationship. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1978;14:398–408. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Gournic SJ, McAfee MP. Perceptions of postdrinking female sexuality: Effects of gender, beverage choice, and drink payment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988;18:1295–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative binomial regression. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2007: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–45 (NIH Publication No. 08-6418B) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knee CR, Neighbors C. Self-determination, perception of peer pressure, and drinking among college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:522–543. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus SJ. Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:58–75. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick JA, Petty RE. Attitude strength: An overview. In: Petty RE, Krosnick JA, editors. Attitude strength: Antecedants and consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons AC, Willott SA. Alcohol consumption, gender identities and women's changing social positions. Sex Roles. 2008;59:694–712. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative Misperceptions and Temporal Precedence of Perceived Norms and Drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Desai S, Kilmer JR, Larimer ME. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:522–528. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Walker DD, Larimer ME. Expectancies and evaluations of alcohol effects among college students: self-determination as a moderator. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:292–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD. Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: some research implications for campus alcohol education programming. International Journal of the Addictions. 1986;21:961–976. doi: 10.3109/10826088609077249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA, Miller DT. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:243–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Lejuez CW, Palfai TP, Slack M. Gender, alcohol consumption, and differing alcohol expectancy dimensions in college drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:298–308. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson C, Darley JM, Messinger CS. “I’m not as thin as you think I am”: The development and consequences of feeling discrepant from the thinness norm. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M. The psychology of social norms. New York: Harper; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Tormala ZL, Clarkson JJ, Petty RE. Resisting persuasion by the skin of one’s teeth: The hidden success of resisted persuasive messages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:423–435. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormala ZL, Petty RE. What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger: The effects of resisting persuasion on attitude certainty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1298–1313. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormala ZL, Rucker DD. Attitude certainty: A review of past findings and emerging perspectives. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2007;1:469–492. [Google Scholar]