Abstract

The destruction of beta cells in type 1 diabetes in humans and in autoimmune diabetes in the NOD mouse model is a consequence of chronic islet inflammation in the pancreas. The T cell-driven autoimmune response is initiated by environmental triggers which are influenced by the state of intestinal homeostasis and the microbiota. The disease process can be separated into two phases: (1) initiation of mild, controlled, long-term infiltration, and (2) propagation of invasive inflammation which quickly progresses to beta cell deletion and autoimmune diabetes. In this review, we will discuss the cellular and molecular triggers that might be required for these two phases in the context of other issues including the unique anatomical location of pancreas, the location of T cell priming, the requirements for islet entry, and the events that ultimately drive beta cell destruction and the onset of diabetes.

Two phases of disease

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disorder driven by beta cell antigen reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells which leads to beta cell destruction within pancreatic islets and hypoglycemia (rise in blood glucose levels) [1]. While B cells are implicated in disease progression, their exact role remains unclear. The spontaneously diabetic NOD mouse has proved to be an invaluable model for the human disease and has provided important mechanistic insight into the possible etiology of T1D [2]. In autoimmune diabetes, CD4+, CD8+ T cells and B cells are all necessary for disease induction. However serum from diabetic mice is not sufficient to transfer disease, suggesting that B cells may contribute as antigen presenting cells [3]. Other cell types including macrophages, dendritic cells and NK cells are also present in the pancreatic infiltrate and can contribute to beta cell destruction [4].

Analyses of the disease progression in NOD mice has revealed two phases which may be distinct [5]. Initial islet infiltration by T cells in NOD mice commences around 3–4 weeks of age. This benign, chronic infiltration is characterized by a peri-insulitic non-invasive cellular infiltrate that lasts until 8–12 weeks of age (insulitis). Similarly, there is a lack of overt disease for years post-detection of autoantibodies in human patients [1]. At a later stage, the infiltration becomes increasingly more destructive, and culminates in the rapid and specific destruction of beta cells. The initial triggers of inflammation in the islets and subsequent beta cell destruction remain obscure. Although there is a substantial genetic component in predisposition to T1D and autoimmune diabetes, environmental factors appear to contribute significantly to disease onset [6]. Viral infection, diet and/or the composition of the mucosal flora have all been implicated as potential environmental triggers.

Progression to the second phase of disease involves invasive insulitis where immune cells invade the entire islet resulting in the rapid and complete destruction of beta cells, leading to hypoglycemia (diabetes). Given the lag phase from establishment of insulitis to the initiation of beta cell destruction, some have suggested that these two phases are separable and are governed by a distinct set of molecular requirements [5].

Understanding the initial disease triggers that lead to “phase one”, loss of tolerance and initiation of cellular infiltration of the pancreas, and “phase two”, the cellular or molecular changes in the islet infiltrate associated with high beta cell destruction, remain obscure. Thus many questions have focused around different aspects of these two phases which constitute the focus of this review: Initiation - What are the key mediators of the initial cellular infiltration of the islets? Propagation - What are the key cellular or molecular changes that lead to beta cell destruction? These will be discussed in this review along with issues that remain unresolved such as the site of APC activation and T cell priming, the route of T cell entry into the islets, the composition of the cellular infiltrate, and how these parameters might change in later stages of the disease.

Initiation

Pathogen trigger

Environmental factors appear to play a significant role in diabetes development [1], and these include exposure to infectious agents. Diabetes can be triggered through infection of beta cells and direct cell lysis by T cells, beta cell death induced by local inflammation, molecular mimicry or cross-recognition of viral and beta cell epitopes by T cell receptors, and activation of self-reactive T cells via presentation of beta antigens in the context of inflammation [6]. In support of the role of viral induction of diabetes, variants of IFIH1, a gene that is involved in anti-viral protection, have been linked to decrease in risk of developing diabetes [7]. Although several viral infections have been implicated in progression to type 1 diabetes, enteroviruses have been reproducibly isolated from recent onset patients and have thus been the focus of considerable recent attention as a possible trigger [6]. Nevertheless, epidemiological studies in humans provide only correlative evidence of diabetes development and viral infections and clearly more definitive analysis needs to be performed.

Commensal trigger

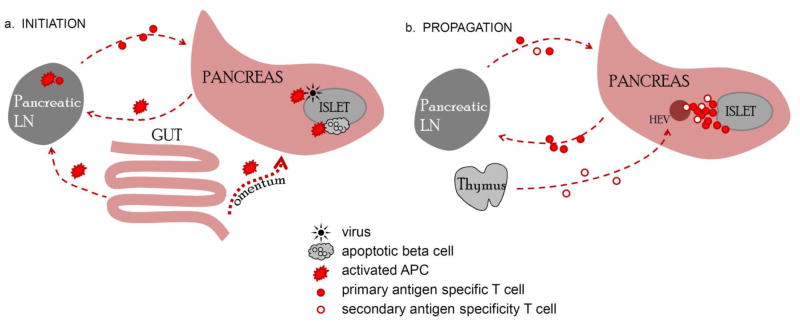

The initial infiltration in the NOD mouse occurs at the time of weaning; implying that changes in the intestinal microflora may provide the trigger that leads to a breakdown in tolerance and initiation of islet infiltration. The initial islet infiltrate is composed of activated macrophages and dendritic cells [8], which as we discuss later, can be a direct conduit to the gut microenvironment. An important, recent realization is that a systemic immune response can be substantially influenced by the intestinal microbiota. Studies have shown a direct link between the composition of the gut microflora and diabetes development [9]. Genetic deletion of MyD88, which abrogates signaling from multiple TLRs, protects NOD mice from diabetes [9]. The protection was due to changes in composition of intestinal microbiota, and was transferable to germ free mice. These data imply a reciprocal relationship between intestinal microbiota and the immune system, with each shaping the development of the other. These findings have direct implications for human disease, as a recent study has shown that children that go on to develop T1D possess a microbiome that is different in its composition from control children [10]. Interestingly, susceptibility to diabetes is also linked with gut “leakiness” that results in increased cell trafficking from the intestines into the peritoneal cavity [11]. Some of the homing molecules involved in trafficking to the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract are the same [12], and thus the PLN is often the preferred site of cell trafficking from the peritoneal cavity [13]. Consequently, the inflammatory state of the intestinal microenvironment can have a direct effect on the activation state of APCs in the PLN (Figure 1A). In addition to possible aberrant APC activation, diabetes patients have reduced numbers of intestinal suppressive CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) [14], which one might speculate leads to increase immune activation.

Figure 1.

Priming of self-reactive T cells and propagation of T cell-driven autoimmune diabetes. A. Antigen presenting cells (APCs) activated in the pancreas by virally infected β cells, apoptotic β cells, or APCs activated by microflora in the peritoneal cavity. B. During chronic insulitis, naïve T cells have the potential to traffic directly to the pancreas via HEVs. Activated T cells infiltrating the pancreas recirculate in the periphery and can return to the pancreas to invade other islets. A this stage PLN play a minor role in recruiting new lymphocytes.

The highly vascularized location of the islets [15] might contribute to more efficient cell recruitment and disease development, but there is currently no evidence to support this notion. The close proximity of the islets to the vasculature might permit a higher frequency of islet antigen “sampling” by circulating T cells, which may in turn increase the probability of T cell activation. However, the pancreatic lymph nodes (PLN) are required for disease initiation [16], suggesting that initial T cell priming may occur in the PLN although it is also possible that they are simply a conduit to the islets. Increased vascularization may also enhance activated/memory T cell homing.

Another interesting aspect of the location of the pancreas in the peritoneal cavity is its envelopment by and connection to the gut via the omentum, a fatty tissue that has poorly understood immunological activity. Recent studies have suggested that omental milky spots, which are clusters of leukocytes found within the omentum have the potential to act as secondary lymphoid organs and induce some CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to antigens administered via intraperitoneal injection, as well as acting as a trap for peritoneal antigens for presentation to previously activated T cells [17]. One could speculate that the omentum is another anatomical location of immunological activity that may influence the inflammatory status in the pancreas and act as a conduit to the intestinal microenvironment (Figure 1A).

It is important to note that diabetes incidence is higher in the Western world and within families from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, suggesting that exposure to more infectious agents and lower hygiene standards may prevent diabetes onset [6]. It is likely that certain bacterial or helminth infections have a protective effect by influencing the development of intestinal microflora and as a result shaping the immune response. For instance, Schistosoma mansoni protects against diabetes in NOD mice by shifting the immune response from Th1 to Th2 response [18], and Salmonella typhimurium infection reduces diabetes incidence by influencing dendritic cells which in turn regulate T cell trafficking to the pancreas [19]. Hence, infectious or enteric agents are not necessarily detrimental in an autoimmune setting, but can rather guide the development of the immune response in either a protective or pathogenic direction. Moreover, the same microbial species can be both protective and detrimental depending on the type of the autoimmune disease, as was shown for intestinal segmented filamentous bacteria that protected against type 1 diabetes and exacerbated rheumatoid arthritis [20,21].

Misinterpreted danger signal – aberrant beta cell death as a trigger

Despite the possible connection between T1D and the microbiota, some data implicate a microbe-independent mode of diabetes induction. For instance, mice lacking both MyD88 and AIRE develop autoimmunity to the same extent as mice lacking AIRE alone [22]. In addition to a viral or bacterial trigger, it is also possible that there is endogenous immune activation. NOD mice exhibit increased beta cell apoptosis prior to any cellular infiltration in the pancreas. Compared to the B6 non-autoimmune prone mouse strain, apoptotic beta cells are not cleared properly in the islets of NOD mice and some beta cells exhibit signs of necrosis [23]. Necrosis, and excessive apoptosis, activate phagocytic cells through various danger signaling molecules released during cell death [24]. High-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) is one such “innate alarmin” molecule that is released from the nucleus of beta cells and has been shown to play a direct role in diabetes development [25]. It is possible that several triggers converge to break self-tolerance. Indeed, one could envisage how aberrantly activated APCs travel from the unique gut microenvironment to the pancreas, take up beta cell apoptotic bodies and present them in the PLN, in a context of danger signals, to prime self-reactive T cells (Figure 1A).

T cell antigen specificity in T1D

There has been considerable debate regarding whether the islet infiltrate is composed primarily of self-reactive T cells or whether there is a substantial degree of bystander recruitment of T cells that are not specific for beta cell antigens. In order to address this issue, we recently made use of a novel retrogenic TCR expression approach to show that TCR specificity is of paramount importance for efficient CD4+ and CD8+ T cell entry and accumulation in the islets [26]. Mixed bone marrow chimeras were generated to create mice that possess two distinct T cell populations; one that expressed islet antigen reactive TCRs and a second that expressed TCRs with irrelevant antigen specificity. This clearly showed that only T cells expressing beta antigen reactive TCRs were able to accumulate in the islets. Moreover, we cloned TCRs from either an islet infiltrating polyclonal population or the spleen of a female NOD mouse to assess the migratory behavior of T cells after the TCRs were re-expressed in retrogenic mice. Strikingly, the majority of islet-derived TCRs facilitated T cell autonomous islet entry, while this did not occur with splenic TCRs [26]. These data clearly imply that T cell islet entry is a tightly controlled event and that beta cell antigen specificity is a precondition of admittance.

Another study reported similar results, albeit obtained through a different approach. The authors monitored infiltration of CD8+ T cells specific to glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit-related protein (IGRP) in a mouse model where the dominant epitope was rendered “invisible” by mutating two TCR contact residues [27]. Neither activated nor naïve CD8+ T cells were able to infiltrate the islets, further supporting the critical importance of TCR specificity in autoimmune response. A recent study reported similar findings when specifically analyzing early time points of T cells infiltration into the islets [28]. Collectively, these observations support the idea that antigen specificity is a requirement for entry/accumulation in the islets. An important consequence of these findings is the renewed possibility of utilizing antigen specificity to direct immunotherapy to the site of inflammation in the pancreas. Novel technologies involving viral transduction of cells with antigen specific TCRs are gaining traction as a therapy for autoimmune diseases [29].

Propagation

Augmentation of T cell pathogenicity in progression to disease

A key question is how the initial chronic phase of disease, which is characterized by non-invasive insulitis, progresses to invasive insulitis, beta cell destruction and overt diabetes [5]. One might argue that the final destruction of beta cells is an unavoidable consequence of chronic inflammation and organ damage. However, there are indications that the final stage of disease might also have a specific trigger. Several changes in the dynamics of the islet infiltrate might precipitate beta cell destruction: (1) expansion/dissemination of highly diabetogenic clones or an increase in T cell pathogenicity, (2) redirection of the autoimmune response to other antigen(s) or epitopes(s), (3) loss of Treg function and/or resistance of effector T cells to immune regulation.

Although recent studies have shown that TCR specificity for beta cell antigens plays a major role regulating T cell homing to the islets [26,27], it is possible that certain antigens are exposed at later stages of disease which may alter the spectrum of diabetogenic T cell clones in the islets. It is also possible that the type or quantity of specific peptides may also change as disease progresses. Either change could be associated with modified function of beta cells, beta cell death, and/or release of initially concealed or repressed antigens. Indeed, several studies have suggested that diabetogenic T cells recognize peptides that have been modified or processed in a unique way, and thus may escape tolerance induction, and that these modifications may be restricted to the islets [8]. For instance, the recently identified diabetes antigen chromogranin A induces higher T cell activation when isolated directly from beta cells, suggesting that the epitope is subjected to some form of beta cell-specific post-translational modification [30]. These types of “neo-antigens” have been identified in other autoimmune diseases and support a common mechanism behind failures in central tolerance [31].

It is possible that there are alterations in T cell trafficking which may increase pathogenicity. For instance, there may be increased trafficking through the islets which enhances surveillance of the organ during the peak of disease. If the islets are more permissive to infiltration later in disease, this could potentially improve the probability for recruiting new clones that may result in antigenic spread. Nevertheless, our studies have suggested that even a high level of inflammation is unable to induce significant accumulation of bystander T cells, and suggests that antigenic specificity remains a prerequisite for islet infiltration even at later stages of disease [26]. Despite these advances, we know little about the relative pathogenicity of the T cells found in islets at different time points, their route of entry, and mechanisms that mediate beta cell destruction.

Given that each islet is initially infiltrated by unique clones [32], one might imagine that the recirculation and amplification of several highly pathogenic clones that originated in one islet and then traffic back to the pancreas could result in invasion and destruction of all islets. Based on studies in our laboratory, we have noticed such peripheral recirculation and amplification of pathogenic clones at later stages of the disease [33]. As the disease progresses, the TCR repertoire might become more restricted as T cells with high avidity are preferentially expanded in the islets [34]. A detailed dissection of these issues is limited by the lack of appropriate tools to track T cell migration in vivo. By using genetically or exogenously marked T cell populations we can determine where T cells are at any specific point in time, but we cannot determine where they have been. As a result, we are unable to distinguish the route and timing of T cell entry and exit from islets, how long they remain in the pancreas, and what the contribution of cellular expansion might have been at any single point in time. Clearly new tools need to be developed to track T cell migration history in vivo.

The apparent increase in T cell pathogenicity may not be an entirely intrinsic effect explained by changes in TCR affinity or specificity alone. One of the events that is associated with decline of beta cell function, and potentially the main precipitating event, is loss of Treg function [35]. The primary mechanisms leading to Treg demise appear to be lack of IL-2 or defects in IL-2R signaling [36,37]. In NOD mice reduced levels of IL-2 and impairment in Treg function were directly linked to IL2 SNPs within the Idd3 susceptibility locus [38]. A key study showed that Treg cells present in the islet infiltrate are actively involved in the regulation of diabetogenic T cell responses, but do not seem to have an effect on initial T cell recruitment to the islets [39]. Acute deletion of Tregs via administration of diphtheria toxin to BDC2.5/NOD.Foxp3DTR+ mice resulted in rapid destruction of beta cells, with 100 percent diabetes development within four days [40]. An important conclusion from this study is that pathogenic effector T cells are present in the islets at the pre-diabetic stage and are capable of rapid beta cell destruction, but are held in check by Tregs. Thus, the enhanced T cell pathogenicity observed in the later stages of disease may be an indirect effect of reduced Treg function [41].

The initial trigger that eventually precipitates this Treg “crash” remains elusive; and recruitment of one (or several) highly pathogenic clone(s) cannot be excluded as a compounding factor. This is relevant because effector T cells have been shown to gain in pathogenicity as disease progresses. Interestingly, studies in both NOD mice and human patients have reported increased resistance of effector T cells to suppression by Foxp3+ Tregs [42,43]. Thus, multiple cell intrinsic and extrinsic factors may impinge on T cells to enhance their diabetogenic potential and subsequent beta cell destruction.

T cell recruitment to and priming in the insulitic microenvironment

Although the PLN is necessary for disease induction, it plays little role in the later stages of disease as demonstrated following surgical removal [16]. This suggests that T cell priming is not required during the latter stages of disease and that the recruitment and activation of new, naive T cell clones is not required for diabetes onset. Alternatively, these data could suggest that de novo T cell priming is continuously required and that this occurs at alternate locations such as within the islets. Indeed analysis of other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as chronic viral infections, suggest that the a productive immune response is sustained by the continual recruitment of naive T cells [44,45]. Thus, it is possible that new, naive clones contribute to the anti-beta cell response and may also contribute to antigenic spread, although neither possibility has been convincingly addressed.

Chronic inflammation often results in the formation of tertiary lymphoid organs (TLOs), with lymphoid cells organized into separate areas, such as granulomas present in bacterial and viral infections. Studies of TLO formation in the islets, their function and contribution to diabetes progression have reported conflicting findings [46,47]. Treatment of NOD mice with FTY720, a drug that limits T cell egress from lymphoid tissues, prevented T cell migration from the PLN and peri-islet infiltrates and blocked diabetes development [46]. The study also showed that FTY720 treatment after insulitis onset prevents disease development, which could indicate that recruitment of new T cell clones later in disease may be important for disease progression or that FTY720 blocked further islet invasion by the cells that were already present in the islet infiltrate [46]. However, prevention of infiltrate organization into separate B and T zones formation by blocking CXCL13, a ligand for the CCR5 chemokine receptor expressed on islet infiltrating B cells, did not have any effect on the composition of the islet infiltrate, B cell somatic hypermutation or disease progression [47]. It is important to note that disease post-CXCL13 blockade was monitored in insulin specific Ig heavy chain transgenic mice that have limited BCR specificity. It is conceivable that a range of BCR specificities might be important for B cell function in diabetes, potentially playing a role in antigenic spread [48]. What is unclear is whether TLO formation has any effect on Treg function or effector T cell resistance in the islets. Based on previous findings [49], one might postulate that germinal center formation in the TLOs could have a negative effect on Foxp3+ Treg stability.

If we accept that there is a continuous recruitment of naïve cells into the autoimmune response, one important factor might be the presence of PNAd+ HEVs within the islet infiltrate and whether this can facilitate naive T cell recruitment [46]. Of note, Rag2−/− mice lack PNAd+ HEVs in the pancreas [46], which suggests that an adaptive immune response is necessary for the development of HEVs in the pancreas. This is consistent with the idea that T cell priming at disease onset is PLN-dependent but that the priming function of the PLN is replaced by other locations, such as insulitic infiltrates (Figure 1B).

Concluding remarks

The complexity of the immune response in type 1 diabetes in humans and autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice mandates a deeper understanding of the cellular dynamics that control islet infiltration and beta cell destruction. Some of the key questions that relate to these issues are: (1) What are the key triggers that initiate inflammation and cellular infiltration into the islets? (2) Which cellular interactions lead to priming and activation of beta cell reactive T cells, where do these interactions take place, and how does this regulate islet inflation? (4) Is there a progressive spread or a narrowing of antigenic specificities over the course of the disease and how does this relate to disease development? (5) Do T cells of different antigenic specificities exhibit different trafficking patterns? (6) Is there one antigen specificity that triggers initial islet infiltration and the final stages of rapid beta cell destruction, and are they the same or different? (7) What propagates the increasingly pathogenic autoimmune response? (8) What leads to the loss of Treg function, and gain of effector T cell resistance to Treg-mediated suppression?

In order to address these questions, novel, innovative tools and technologies will need to developed and employed. For instance, direct in vivo monitoring and tracking of islet infiltration and cellular migration will likely provide essential information on where T cells enter the islets, how long they remain in the islets, whether the infiltrating cells invade the islets or exit the infiltrate and recirculate to the periphery, what contribution naïve, activated and locally expanded cells provide to the infiltrate and how these parameters change at the later stages of the disease. Intravital microscopy is an approach that could address some of these important questions. However, the location of the islets within the exocrine tissue of the pancreas, the difficulty at maintaining oxygenation and temperature of the pancreas post-surgical exposure, the relatively short duration of the imaging process [15], and the necessity to track large unphysiological numbers of activated transferred cells [50] present significant challenges for the approach. Clearly enhanced intravital microscopy techniques and innovative genetic cellular tracking technologies will have to be developed to address these critical questions. A better understanding of these cellular dynamics, together with the molecules and mechanisms that trigger and mediate T cell islet infiltration and beta cell destruction will allow us to target these pathways and potentially develop novel therapies to prevent or cure T1D.

Highlights.

Virus, mucosal flora or aberrant beta cell death/clearance breaks T cell tolerance

Beta cell antigen specificity is a pre-requisite for T cell islet infiltration

Increased T cell pathogenicity and loss of Treg function precipitate diabetes onset

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI39480 and DK089125, D.A.A.V.), a JDRF Postdoctoral Fellowship (3-2009-594, M.B.), NCI Comprehensive Cancer Center Support CORE grant (CA21765, D.A.A.V.), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC, D.A.A.V.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Bluestone JA, Herold K, Eisenbarth G. Genetics, pathogenesis and clinical interventions in type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2010;464:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nature08933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson MA, Leiter EH. The NOD mouse model of type 1 diabetes: as good as it gets? Nat Med. 1999;5:601–604. doi: 10.1038/9442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong FS, Hu C, Xiang Y, Wen L. To B or not to B--pathogenic and regulatory B cells in autoimmune diabetes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehuen A, Diana J, Zaccone P, Cooke A. Immune cell crosstalk in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:501–513. doi: 10.1038/nri2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andre I, Gonzalez A, Wang B, Katz J, Benoist C, Mathis D. Checkpoints in the progression of autoimmune disease: lessons from diabetes models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2260–2263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippi CM, von Herrath MG. Viral trigger for type 1 diabetes: pros and cons. Diabetes. 2008;57:2863–2871. doi: 10.2337/db07-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nejentsev S, Walker N, Riches D, Egholm M, Todd JA. Rare variants of IFIH1, a gene implicated in antiviral responses, protect against type 1 diabetes. Science. 2009;324:387–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1167728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadinski B, Kappler J, Eisenbarth GS. Molecular targeting of islet autoantigens. Immunity. 2010;32:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, Stranges PB, Avanesyan L, Stonebraker AC, Hu C, Wong FS, Szot GL, Bluestone JA, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, Novelo LL, Casella G, Drew JC, Ilonen J, Knip M, Hyoty H, et al. Toward defining the autoimmune microbiome for type 1 diabetes. ISME J. 2011;5:82–91. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapone A, de Magistris L, Pietzak M, Clemente MG, Tripathi A, Cucca F, Lampis R, Kryszak D, Carteni M, Generoso M, et al. Zonulin upregulation is associated with increased gut permeability in subjects with type 1 diabetes and their relatives. Diabetes. 2006;55:1443–1449. doi: 10.2337/db05-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaarala O. The role of the gut in beta-cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: a hypothesis. Pediatr Diabetes. 2000;1:217–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1399543x.2000.010408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turley SJ, Lee JW, Dutton-Swain N, Mathis D, Benoist C. Endocrine self and gut non-self intersect in the pancreatic lymph nodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17729–17733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509006102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badami E, Sorini C, Coccia M, Usuelli V, Molteni L, Bolla AM, Scavini M, Mariani A, King C, Bosi E, et al. Defective Differentiation of Regulatory FoxP3+ T Cells by Small-Intestinal Dendritic Cells in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:2120–2124. doi: 10.2337/db10-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinic MM, von Herrath MG. Real-time imaging of the pancreas during development of diabetes. Immunol Rev. 2008;221:200–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagnerault MC, Luan JJ, Lotton C, Lepault F. Pancreatic lymph nodes are required for priming of beta cell reactive T cells in NOD mice. J Exp Med. 2002;196:369–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rangel-Moreno J, Moyron-Quiroz JE, Carragher DM, Kusser K, Hartson L, Moquin A, Randall TD. Omental milky spots develop in the absence of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells and support B and T cell responses to peritoneal antigens. Immunity. 2009;30:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaccone P, Fehervari Z, Jones FM, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Dunne DW, Cooke A. Schistosoma mansoni antigens modulate the activity of the innate immune response and prevent onset of type 1 diabetes. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1439–1449. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raine T, Zaccone P, Mastroeni P, Cooke A. Salmonella typhimurium infection in nonobese diabetic mice generates immunomodulatory dendritic cells able to prevent type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2006;177:2224–2233. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •20.Kriegel MA, Sefik E, Hill JA, Wu HJ, Benoist C, Mathis D. Naturally transmitted segmented filamentous bacteria segregate with diabetes protection in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11548–11553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108924108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •21.Wu HJ, Ivanov II, Darce J, Hattori K, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Littman DR, Benoist C, Mathis D. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2010;32:815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.001. These two manuscripts show that modification of the immune system by one type of bacteria can lead to either protection or exacerbation of autoimmune disease, depending on the type of the response driving the disease induction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray DH, Gavanescu I, Benoist C, Mathis D. Danger-free autoimmune disease in Aire-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18193–18198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709160104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S, Zhong J, Yang P, Gong F, Wang CY. HMGB1, an innate alarmin, in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;3:24–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green DR, Ferguson T, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic and tolerogenic cell death. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:353–363. doi: 10.1038/nri2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han J, Zhong J, Wei W, Wang Y, Huang Y, Yang P, Purohit S, Dong Z, Wang MH, She JX, et al. Extracellular high-mobility group box 1 acts as an innate immune mediator to enhance autoimmune progression and diabetes onset in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:2118–2127. doi: 10.2337/db07-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••26.Lennon GP, Bettini M, Burton AR, Vincent E, Arnold PY, Santamaria P, Vignali DA. T cell islet accumulation in type 1 diabetes is a tightly regulated, cell-autonomous event. Immunity. 2009;31:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••27.Wang J, Tsai S, Shameli A, Yamanouchi J, Alkemade G, Santamaria P. In situ recognition of autoantigen as an essential gatekeeper in autoimmune CD8+ T cell inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9317–9322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913835107. These two papers show that islet infiltration is a tightly regulated event and is permissive only to antigen specific T cells whose antigen is expressed in the pancreas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calderon B, Carrero JA, Miller MJ, Unanue ER. Cellular and molecular events in the localization of diabetogenic T cells to islets of Langerhans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1561–1566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018973108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright GP, Notley CA, Xue SA, Bendle GM, Holler A, Schumacher TN, Ehrenstein MR, Stauss HJ. Adoptive therapy with redirected primary regulatory T cells results in antigen-specific suppression of arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19078–19083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907396106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stadinski BD, Delong T, Reisdorph N, Reisdorph R, Powell RL, Armstrong M, Piganelli JD, Barbour G, Bradley B, Crawford F, et al. Chromogranin A is an autoantigen in type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:225–231. doi: 10.1038/ni.1844. This study identified the long sort after target antigen of the widely used BDC2.5 TCR, providing another potentially important beta cell antigen for further study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doyle HA, Mamula MJ. Posttranslational modifications of self-antigens. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1050:1–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1313.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarukhan A, Bedossa P, Garchon HJ, Bach JF, Carnaud C. Molecular analysis of TCR junctional variability in individual infiltrated islets of non-obese diabetic mice: evidence for the constitution of largely autonomous T cell foci within the same pancreas. Int Immunol. 1995;7:139–146. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bettini M, Szymczak-Workman AL, Forbes K, Castellaw AH, Selby M, Pan X, Drake CG, Korman AJ, Vignali DA. Cutting edge: Accelerated autoimmune diabetes in the absence of LAG-3. J Immunol. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100714. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han B, Serra P, Yamanouchi J, Amrani A, Elliott JF, Dickie P, Dilorenzo TP, Santamaria P. Developmental control of CD8 T cell-avidity maturation in autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1879–1887. doi: 10.1172/JCI24219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bettini M, Vignali DA. Regulatory T cells and inhibitory cytokines in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:612–618. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •36.Tang Q, Adams JY, Penaranda C, Melli K, Piaggio E, Sgouroudis E, Piccirillo CA, Salomon BL, Bluestone JA. Central role of defective interleukin-2 production in the triggering of islet autoimmune destruction. Immunity. 2008;28:687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.016. This study highlights a key role for reduced IL2 production is causing Treg fragility and enhanced autoimmune diabetes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long SA, Cerosaletti K, Bollyky PL, Tatum M, Shilling H, Zhang S, Zhang ZY, Pihoker C, Sanda S, Greenbaum C, et al. Defects in IL-2R signaling contribute to diminished maintenance of FOXP3 expression in CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T-cells of type 1 diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2010;59:407–415. doi: 10.2337/db09-0694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •38.Yamanouchi J, Rainbow D, Serra P, Howlett S, Hunter K, Garner VE, Gonzalez-Munoz A, Clark J, Veijola R, Cubbon R, et al. Interleukin-2 gene variation impairs regulatory T cell function and causes autoimmunity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:329–337. doi: 10.1038/ng1958. This study shows direct genetic linkage of reduced IL2 production and Treg fragility to a single locus in NOD mice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Z, Herman AE, Matos M, Mathis D, Benoist C. Where CD4+CD25+ T reg cells impinge on autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1387–1397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••40.Feuerer M, Shen Y, Littman DR, Benoist C, Mathis D. How punctual ablation of regulatory T cells unleashes an autoimmune lesion within the pancreatic islets. Immunity. 2009;31:654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.023. This seminal work exposed the critical and continuous regulation of the autoimmune response in the islets by Tregs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brusko TM, Wasserfall CH, Clare-Salzler MJ, Schatz DA, Atkinson MA. Functional defects and the influence of age on the frequency of CD4+ CD25+ T-cells in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:1407–1414. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You S, Belghith M, Cobbold S, Alyanakian MA, Gouarin C, Barriot S, Garcia C, Waldmann H, Bach JF, Chatenoud L. Autoimmune diabetes onset results from qualitative rather than quantitative age-dependent changes in pathogenic T-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:1415–1422. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider A, Rieck M, Sanda S, Pihoker C, Greenbaum C, Buckner JH. The effector T cells of diabetic subjects are resistant to regulation via CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7350–7355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vezys V, Masopust D, Kemball CC, Barber DL, O’Mara LA, Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Ahmed R, Lukacher AE. Continuous recruitment of naive T cells contributes to heterogeneity of antiviral CD8 T cells during persistent infection. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2263–2269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao J, Perlman S. De novo recruitment of antigen-experienced and naive T cells contributes to the long-term maintenance of antiviral T cell populations in the persistently infected central nervous system. J Immunol. 2009;183:5163–5170. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Penaranda C, Tang Q, Ruddle NH, Bluestone JA. Prevention of diabetes by FTY720-mediated stabilization of peri-islet tertiary lymphoid organs. Diabetes. 2010;59:1461–1468. doi: 10.2337/db09-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henry RA, Kendall PL. CXCL13 blockade disrupts B lymphocyte organization in tertiary lymphoid structures without altering B cell receptor bias or preventing diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2010;185:1460–1465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian J, Zekzer D, Lu Y, Dang H, Kaufman DL. B cells are crucial for determinant spreading of T cell autoimmunity among beta cell antigens in diabetes-prone nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:2654–2661. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsuji M, Komatsu N, Kawamoto S, Suzuki K, Kanagawa O, Honjo T, Hori S, Fagarasan S. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer’s patches. Science. 2009;323:1488–1492. doi: 10.1126/science.1169152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calderon B, Carrero JA, Miller MJ, Unanue ER. Entry of diabetogenic T cells into islets induces changes that lead to amplification of the cellular response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1567–1572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018975108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]