Abstract

Prescription medication borrowing can result in adverse health outcomes. We aimed to study the patterns of borrowing prescription medications in an adult urban population seeking healthcare in the outpatient, emergency, and inpatient units of an urban medical center. Participants indicated whether they (1) had a primary care doctor, medical insurance, a prior history of substance abuse, psychiatric disorders, or chronic pain; and (2) had borrowed a prescription medication. If so, they noted the medication obtained, source, frequency of use, and reasons why they had not obtained a prescription from a licensed medical provider. Of the 641 participants, most were African American (75%), urban residents (75%), high school educated or less (71%), and lacked full-time employment (68%). Many had health insurance (90%) and had recently seen their primary medical provider (75%). Eighteen percent reported ever borrowing a prescription medication. On multivariate analysis, history of chronic pain was marginally associated with increased medication borrowing (odds ratio [OR] = 1.58) while having Medicare insurance (OR = 0.436) or a primary care medical provider routinely ask about medication usage (OR = 0.589) were significantly associated with decreased medication borrowing. The most commonly obtained medications were for pain (74%), usually in the form of opioids, and were obtained from a family member (49%) or friend (38%). Thirty-five percent of those who borrowed medications did so more than once a year, with lack of convenient access to medical care the most frequently cited reason for use (67%). Only a third of those who borrowed medications had informed their primary medical providers of the behavior. In conclusion, borrowing prescription medications is a common behavior in the population studied. Further research is warranted into interventions to reduce such use, especially the impact of methods to improve the convenience of contacting licensed medical providers.

Keywords: Prescription medication borrowing, Loaning, Diversion, Urban health

Background

The diversion of prescription medications without the involvement of a medical professional, besides being illegal under federal law, is also a growing public health concern.1-4 Primarily defined as the giving or selling of medications to someone (i.e., sharing) or the taking or purchasing of someone else’s medication (i.e., borrowing), these behaviors cause great concern among healthcare providers because of the many potential adverse consequences.5,6 Chief among these are (1) delay in treatment for a condition due to self-treatment with the borrowed medication; (2) erroneous perceptions of ineffective treatment due to incorrect dosage or treatment duration; (3) increase in antibiotic resistance; (4) increase in risk of adverse events directly from the medication, as well as from drug–food and drug–drug interactions.2 A significant number of emergency department visits and the majority of overdose deaths are associated with the diversion of prescription drugs.4,7 Though this diversion is particularly significant for opioids, other medications are also involved.3,5,6

Past studies have examined both the sharing and borrowing of prescription medications, yet those who borrow medications are intrinsically at higher risk for the adverse effects discussed above.2 Among the studies examining the borrowing of prescription medications, the prevalence of medication borrowing has ranged from 5% to 35%, with most national studies placing the prevalence around 23–26%.2,7-14

The influence of physical attributes, such as gender and age, on the rate of medication borrowing, has also been investigated. Studies suggest that although women share medications more often than men, they seem to borrow medications equally (range, 13.9–29.6% for men and 15.1–29.8% for women). 2,8,12 The prevalence of medication borrowing has been shown to increase through adolescence, peak during the third decade of life, and then generally declines with increasing age.12

The diversity of substances involved in medication borrowing has been found to be surprisingly extensive. Opiates and hypnotics are the most frequently borrowed prescription medications, though there are many other classes of medications involved.2 A study of stimulant diversion demonstrated that prescription analgesics were borrowed at the alarmingly high lifetime rate of 35%.10 Other medications found to be borrowed include acne medications, allergy medications, non-opiate pain medications, antidepressants, antibiotics, asthma medications, birth control pills, and herbal supplements.10,13,14

Unfortunately, despite the above data, the factors associated with medication borrowing remain largely unknown. Among women of reproductive age, the primary rationale was already having a medicine but not currently having it on hand or having the same problem as the person who had the medicine.8 Additional rationales cited include a willingness to borrow medications if they were from a family member, if it was an emergency, if cost was an issue, or for a symptom such as pain.2,8 Interestingly, a desire to get high or “feel good” as a result of the borrowed medication seems rare among adults.2

Little research has examined medication borrowing based on location, such as an urban or rural setting. Urban populations are of particular interest because they are the location of many large academic health centers and a majority of the US population. Additionally, they typically contain higher rates of ethnic minorities, with wide disparities in wealth living in close proximity to one another, which are often associated with disparities in the access to comprehensive primary medical care.15-17 Through national studies, it is also known that areas where illicit (illegal and unregulated) drug use is high, the population is typically of a lower socioeconomic status, with lower levels of educational attainment, and a higher proportion of ethnic minorities.18 Contradicting these findings however, is the one national study of medication borrowing among an urban population which concluded that Caucasians borrowed medications just as often as African Americans, and that household income did not significantly influence this behavior.2 An additional study of injection drug users reported frequent antibiotic exposure, though only a minority identified nonprovider sources for the medication.19

Few have examined the medication borrowing of patients presenting for medical care. Studies to date have either focused on overdose victims presenting to the emergency department or the use of leftover antibiotics from a prior illness.7,20 In order for medical providers to enhance the safety of their patients, we must understand the prevalence of borrowing among patients presenting for medical care and factors which might increase or reduce the likelihood of borrowing. To begin to fill these gaps in literature, we conducted a study to examine these issues among individuals presenting for medical care at an urban medical center.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited from four clinical sites at an urban academic medical center: (1) emergency department walk-in ambulatory clinic, (2) internal medicine residency continuity practice, (3) internal medicine faculty practice, and (4) general medicine inpatient floors.

The eligibility criteria were an ability to speak English and age of ≥18 years. Participants were excluded from the study if they required immediate medical attention, as determined by the patient’s care providers, or were unable to provide informed consent due to a lack of understanding or altered mental status. Direct advertising to patients and physician referrals were not used for recruitment.

Informed consent and study interviews were conducted while participants waited to be seen (outpatient) or the same day of recruitment (inpatient). All interviews were conducted within the privacy of a room. During the interview, participants were assured of the confidential nature of the survey. At the end of the interview, participants received a public transportation token (valued at $2) in appreciation for their contribution to this study. The Temple University Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Data Collection

Participant recruitment and interviews were conducted by individual members of the study team, which included one internal medicine attending physician (LW), an internal medicine resident physician (SE), a clinical pharmacist (NP), and three clinical pharmacy postgraduate research students (KS, MM, and BW). All study team members underwent the same series of two detailed training sessions, administered by a single senior member of the study team (LW), outlining proper recruitment procedures and survey administration. Each member of the study team worked independently to recruit and administer the survey among a convenience sample of patients waiting to be seen in one of four study sites during daytime hours. All data were collected in a face-to-face interview, which took less than 10 minutes to complete.

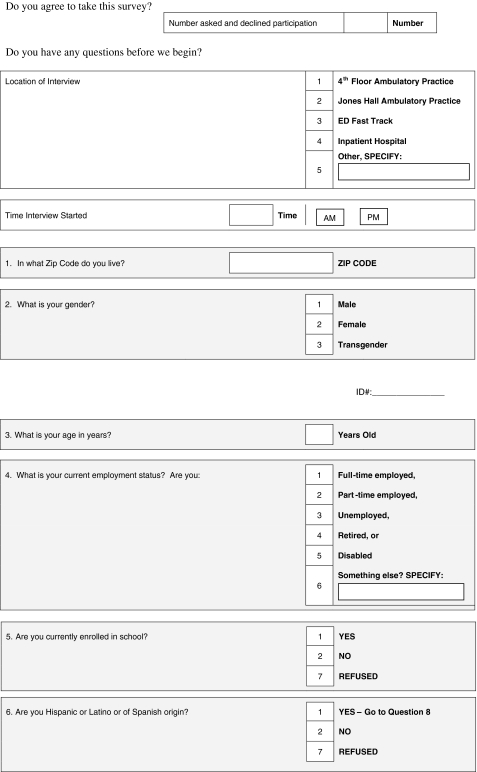

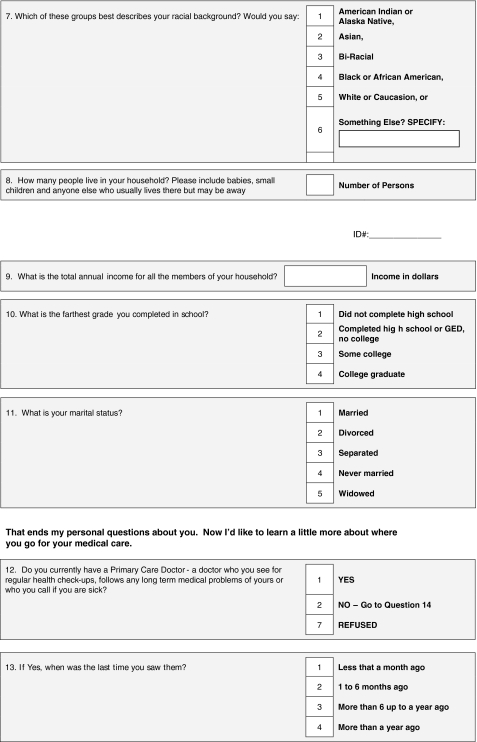

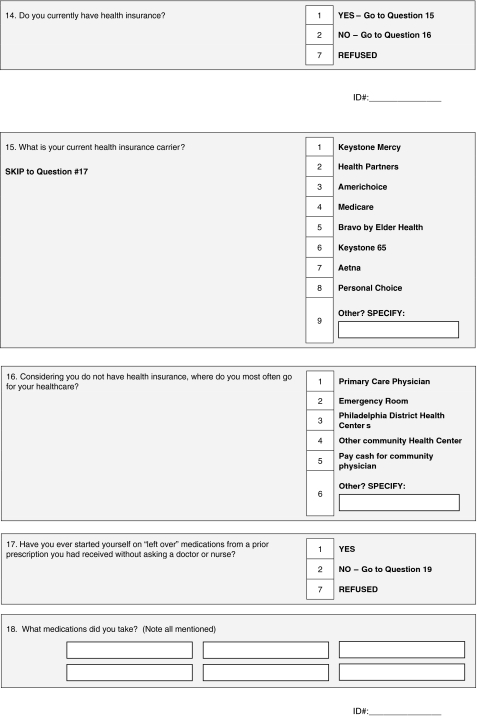

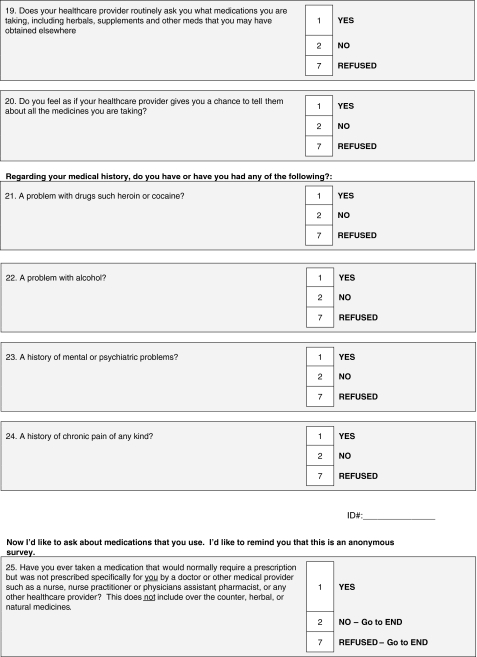

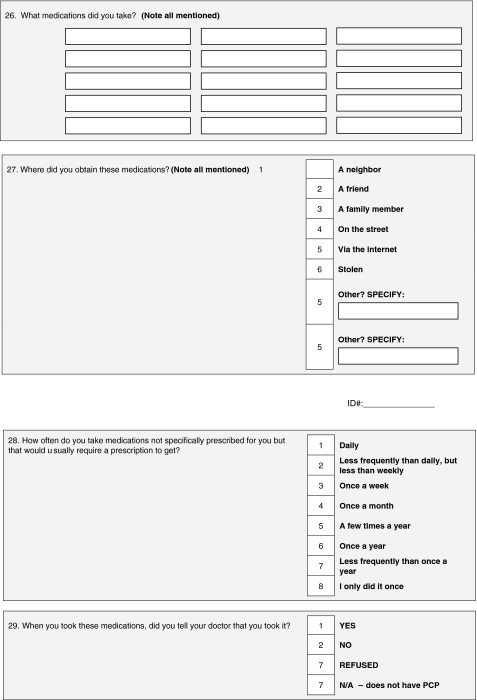

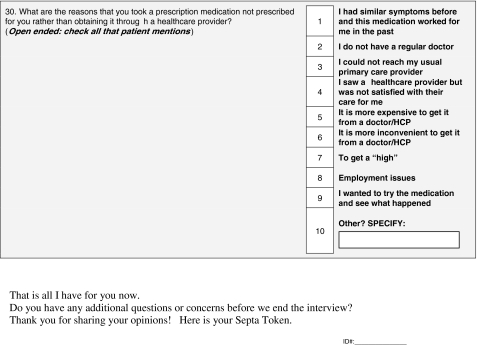

The survey instrument was developed by the research team using elements of existing surveys on this topic supplemented by the clinical experience of the physicians and pharmacists on the team.2,8,12 The final survey (Appendix) was pretested for clarity and content on a sample of 20 participants; though the only changes made after the pretest was reordering of questions to improve clarity. The results of the pretest were not included in the final results. The first portion of the survey contained items on (a) demographic factors, (b) access to a primary care physician and health insurance status, and (c) medical and social problems. Additional questions were asked about the participants’ interactions with their primary care physician. The participant was then asked “Have you ever taken a medication that would normally require a prescription but was not prescribed specifically for you?” All participants who answered affirmatively were asked details about the medications used and underlying rationale for borrowing the medication.

Analysis

Collected data were entered into a web-based program (Surveymonkey.com Corporation, Portland, OR) in an ongoing manner by the interviewers. This program summarized and exported all data into Microsoft Excel for Windows® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). All statistical analyses were then performed using SPSS, version 17.0.

The primary outcome measure was use of prescription medications without a prescription (borrowing). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study sample overall, and by outcome group. Categorical demographic variables, as well as variables of interest generated from the survey, were described using frequencies and percentages, while age measured on a continuum was described using the mean and standard deviation statistics. Each borrowed medication was classified according Lexi-Comp Online Pharmacologic Category and subsequently the most common use was assumed as the indication.

Chi-square tests of association were used to examine bivariate relationships between outcome and categorical independent variables of interest. Outcome groups were compared according to mean age using an independent sample t test. A multivariate binary logistic regression model was generated with the dichotomous outcome measure regressed on independent variables emerging predictive at the 0.20 level in bivariate analyses. Independent variables examined are listed in Table 1. Factors emerging predictive at the 0.20 level were age, race, insurance carrier, query about medication use by primary care medical provider (PCP), history of drug abuse, mental illness, and chronic pain.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Demographic variable | Base sample no. (%) | Borrowed medicine no. (%) | Did not borrow medicine no. (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 641 (100) | 116 (18.1) | 525 (81.9) | NA |

| Age | 18 to 92 (median, 49 years) | 45.61 (14.36) | 49.57 (16.88) | 0.016 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 41% | 51 (44) | 211 (40.2) | 0.684 |

| Female | 59% | 65 (56) | 313 (59.6) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 158 (24.7) | 28 (24.1) | 130 (24.9) | 0.615 |

| Divorced | 79 (12.4) | 11 (9.5) | 68 (13.0) | |

| Separated | 42 (6.6) | 9 (7.8) | 33 (6.3) | |

| Never married | 284 (44.4) | 57 (49.1) | 227 (43.4) | |

| Widowed | 76 (11.9) | 11 (9.5) | 65 (12.4) | |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 483 (75.4) | 96 (82.8) | 387 (73.7) | 0.076 |

| Caucasian | 74 (11.5) | 7 (6) | 67 (12.8) | |

| Other | 84 (13.1) | 13 (11.2) | 71 (13.5) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 66 (10.3) | 10 (8.6) | 56 (10.7) | 0.512 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 575 (89.7) | 106 (91.4) | 469 (89.3) | |

| Recruitment sites | ||||

| ED | 159 (24.8) | 26 (22.4) | 133 (25.3) | 0.682 |

| Resident internal medicine practice | 177 (27.6) | 35 (30.2) | 142 (27) | |

| Faculty internal medicine practice | 139 (21.7) | 22 (19 | 117 (22.3) | |

| Inpatient wards | 166 (25.9) | 33 (28.4) | 133 (25.3) | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 196 (30.6) | 33 (28.4) | 163 (31.1) | 0.221 |

| Completed high school or GED | 258 (40.2) | 46 (39.7) | 212 (40.5) | |

| Some college | 95 (14.8) | 24 (20.7) | 71 (13.5) | |

| College graduate | 91 (14.2) | 13 (11.2) | 78 (14.9) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full time | 204 (31.8) | 40 (34.5) | 164 (31.2) | 0.36 |

| Part time | 41 (6.4) | 8 (6.9) | 33 (6.3) | |

| Unemployed | 154 (24) | 28 (24.1) | 126 (24) | |

| Retired | 119 (18.6) | 14 (12.1) | 105 (20) | |

| Disabled | 123 (19.2) | 26 (22.4) | 97 (18.5) | |

| Currently have a PCP | ||||

| Yes | 546 (85.2) | 98 (84.5) | 448 (85.3) | 0.815 |

| No | 95 (14.8) | 18 (15.5) | 77 (14.7) | |

| Last seen by PCP | ||||

| <1 month | 181 (28.2) | 28 (28.6) | 153 (34.2) | 0.246 |

| 1–6 months | 251 (39.2) | 43 (43.9) | 208 (46.5) | |

| >6 months–1 year | 48 (7.5) | 13 (13.3) | 35 (7.8) | |

| >1 year | 65 (10.1) | 14 (14.3) | 51 (11.4) | |

| Currently have health insurance | ||||

| Yes | 574 (89.5) | 102 (87.9) | 472 (89.9) | 0.529 |

| No | 67 (10.5) | 14 (12.1) | 53 (10.1) | |

| Insurance carrier | ||||

| Medicaid | 247 (38.5) | 56 (48.7) | 191(36.7) | 0.007 |

| Medicare | 138 (21.5) | 12 (10.4) | 126 (24.2) | |

| Private | 184 (28.7) | 33 (28.7) | 151 (29.0) | |

| Uninsured | 67 (10.5) | 14 (12.2) | 53 (10.2) | |

| Routinely asked about medication usage by PCP | ||||

| Yes | 525 (81.9) | 84 (72.4) | 441 (84.2%) | 0.002 |

| No | 113 (17.6) | 32 (27.6) | 81 (15.5%) | |

| Has a chance to tell PCP about medication usage | ||||

| Yes | 562 (87.7) | 98 (84.5) | 464 (88.4) | 0.358 |

| No | 77 (12.0) | 18 (15.5) | 59 (11.2) | |

| History of drug abuse | ||||

| Yes | 78 (12.2) | 23 (19.8) | 55 (10.5) | 0.005 |

| No | 563 (87.8) | 93 (80.2) | 470 (89.5) | |

| History of alcohol abuse | ||||

| Yes | 60 (9.4) | 14 (12.1) | 46 (8.8) | 0.271 |

| No | 580 (90.5) | 102 (87.9) | 478 (91.2) | |

| History of mental illness | ||||

| Yes | 89 (13.9) | 22 (19) | 67 (12.8) | 0.08 |

| No | 552 (86.1) | 94 (81) | 458 (87.2) | |

| History of chronic pain | ||||

| Yes | 224 (34.9) | 50 (43.1) | 174 (33.1) | 0.042 |

| No | 417 (65.1) | 66 (56.9) | 351 (66.9) | |

PCP primary care medical provider

Results

Participant Characteristics (Table 1)

Over a 5 month period (March–August 2008), a total of 805 individuals were approached to complete the questionnaire and 643 agreed to participate, yielding a response rate of 80%. Two responses were later excluded due to missing data, thus 641 respondents are included in the final analysis.

Participants were recruited in roughly equal proportions from the four recruitment sites. They ranged in age from 18 to 92 years (median, 49 years old) with 59% female and 41% male. The sample was primarily African American (75%) with 12% Caucasian, 10% Hispanic, and 3% other. Seventy-five percent of participants were residents of the city of Philadelphia, 71% had a high school education or less, 68% had less than full-time employment, and the median annual self-reported household income was $12,000 (range, $0–360,000). Approximately 90% of respondents had health insurance and, of these, 39% carried a Medicaid insurance plan. Most respondents (85%) stated that they had a primary care provider and 75% of those had seen them within the past year.

Findings

Overall, 18% (N = 116) of respondents reported ever borrowing a prescription medication (Table 1). Medication usage did not differ among the four survey recruitment sites. Univariate analyses demonstrated that younger age, being African American, having Medicaid, having a PCP who does not routinely question medication usage, and having a history of drug abuse, mental illness, and chronic pain were all associated with increased medication borrowing at the 0.20 level. Multivariate logistic regression modeling demonstrated that a history of chronic pain (odds ratio [OR] = 1.58, p = 0.055) was marginally associated with increased medication borrowing while subjects with Medicare (OR = 0.44, p = 0.03) or a PCP that routinely asked about medication usage (OR = 0.59, p = 0.049) were less likely to borrow medications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors related to medication borrowing

| Variables in the equation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% CI for Exp (B) | |||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Step 1a | Age | −.008 | .008 | 1.004 | 1 | .316 | .992 | .977 | 1.008 |

| AA_race (1) | .646 | .369 | 3.067 | 1 | .080 | 1.908 | .926 | 3.933 | |

| Medicare (1) | −.831 | .382 | 4.717 | 1 | .030 | .436 | .206 | .922 | |

| Medicaid (1) | −.021 | .253 | .007 | 1 | .932 | .979 | .597 | 1.606 | |

| ASKMEDS (1) | −.530 | .269 | 3.892 | 1 | .049 | .589 | .348 | .997 | |

| Drugs (1) | .296 | .319 | .861 | 1 | .354 | 1.344 | .720 | 2.509 | |

| Mental (1) | .327 | .318 | 1.053 | 1 | .305 | 1.386 | .743 | 2.586 | |

| Pain (1) | .454 | .237 | 3.667 | 1 | .055 | 1.575 | .989 | 2.508 | |

| Constant | −1.355 | .563 | 5.795 | 1 | .016 | .258 | |||

aLogistic regression modeling probability of medication borrowing

Nearly half of respondents who reported ever borrowing medications did so one or more times during the past year, though only a minority did so once a month or more (14%) (Table 3). Most (95/11 or 82%) reported borrowing only a single type of medication, though 25% (29/116) were unable to recall the name of the specific medication taken. Ultimately, among the 89 respondents able to recall the name of a specific medication taken, 27 distinct medications were identified (Table 3). Opioids (42/89 or 47%), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (25/89 or 28%), benzodiazepines (14/89 or 16%), and antihypertensives (10/89 or 11%) were the most frequently identified medication classes.

Table 3.

Characteristics of those who had ever borrowed medications

| Variable | Base sample no. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of medications borrowed | N = 116 |

| 1 | 95 (81.9) |

| 2 | 15 (12.9) |

| 3 | 3 (2.6) |

| 4 | 3 (2.6) |

| Frequency of medication borrowing | N = 116 |

| Daily | 4 (3.4) |

| More than daily, less than weekly | 4 (3.4) |

| Once a week | 6 (5.2) |

| Once a month | 3 (2.6) |

| A few times per year | 24 (20.7) |

| Once a year | 13 (11.2) |

| Less than once a year | 18 (15.5) |

| Once ever | 44 (37.9) |

| Frequency (by medication class)b | N = 89a |

| Opioids (schedule II–IV) | 42 (47.19) |

| NSAIDs and COX-2 | 25 (28.09) |

| Benzodiazepines | 14 (15.73) |

| Antihypertensives | 10 (11.24) |

| Antibiotics | 5 (4.31) |

| Other | 16 (17.98) |

| Indicationb | N = 116 |

| Pain | 86 (74.14) |

| Anxiety and depression | 16 (13.79) |

| Heart diseasea | 11 (9.48) |

| Infection | 9 (7.76) |

| Allergies | 4 (3.45) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 3 (2.59) |

| Substance abuse | 4 (3.45) |

| Breathing disorders (asthma/emphysema) | 2 (1.72) |

| Other (i.e., emergency contraception and seizures) | 11 (9.48) |

| Told provider about medication use | N = 116 |

| Yes | 39 (33.6) |

| No | 76 (65.5) |

| No primary care physician | 1 (0.9) |

| Reason for borrowing medicationsb | N = 116 |

| Convenience of obtaining (i.e., “could not reach my usual doctor” or “it is inconvenient to call my doctor”) | 78 (67.2) |

| Self-medication (i.e., “had similar symptoms in the past” or “I wanted to see what happened”) | 42 (36.2) |

| Need to get high | 11 (9.48) |

| Cost | 9 (7.76) |

| Source of borrowed medicationsb | N = 116 |

| Family member | 60 (51.72) |

| Friend | 46 (39.66) |

| Someone on the street | 14 (12.07) |

| Via internet | 2 (1.72) |

NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

aN = 89 subjects able to identify at least one borrowed medication by name

bSum of percents do not add to 100% due to subjects being able to respond to more than one category

When data were analyzed according to symptoms for borrowing a medication, pain (86/116 or 74%), anxiety and depression (16/116 or 14%), heart disease (10/116 or 9%), and infection (9/116 or 8%) were most frequently cited (Table 3). Less frequently mentioned were allergies, gastrointestinal disorders, substance abuse, and breathing disorders (i. e., asthma/emphysema). Convenience was cited by two thirds (78/116 or 67%) of respondents as a rationale for borrowing a medication. Self-medication (defined as a desire to “try the medication and see what happened” or taking a medication which worked in the past for similar symptoms) was also cited by a third of respondents (36%; note: multiple reasons could be stated for the behavior). A smaller proportion of respondents stated “a need to get a high,” cost or overall lack of access to medical care as significant influences on their decision to borrow medications. The source of the medications was most commonly a family member (60/116 or 52%) or friend (46/116 or 40%), with fewer respondents obtaining the medication from “someone on the street” (14/116 or 12%) or via the internet (2/116 or 2%).

Having a clearly delineated PCP did not significantly impact on the rate of medication borrowing, nor did the frequency with which they saw their PCP. As stated above, those whose PCP routinely asked about which medications they were taking (OR=0.59, p=0.049) were significantly less likely to have borrowed medications on multivariate analysis (Table 2). Although a large majority (84/116 or 72%) of respondents who had borrowed medications reported that their PCP routinely asked them about the medications they were taking, or gave them a chance to tell them about all the medicines they were taking (98/116 or 85%), only a third (39/116 or 34%) reported telling their PCP about their medication borrowing behavior (Tables 1 and 3).

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge examining the medication borrowing behaviors of an adult urban population seeking medical care. Almost one fifth of respondents reported ever borrowing a medication, with about half of those doing so at least once within the past year. The prevalence of medication borrowing in our study population was similar to those found in other broad based observational studies involving specific ethnic groups and those of higher socioeconomic status. Since the prevalence of medication borrowing did not significantly differ between the four clinical sites in our study, these findings suggest that the prevalence may be similar no matter where a patient presents for medical care.

The specific medications borrowed were consistent with prior reports, with some important exceptions.2,12 Similar to past studies, we found that pain medications were among the most frequently borrowed.2,11,21 This may be because: (1) pain is a symptom that is felt by the patient and it may negatively impact the patient’s quality of life from day to day; (2) Controlled substances have strict federal regulation and are more likely to be diverted and thus providers are more cautious in prescribing these agents; (3) Given the addictive potential of these drugs, many providers reserve them as a last agent of choice. However, as opposed to other studies which found that allergy medications were frequently borrowed, we did not find this to be the case in our adult urban patient population.2 This difference may be partly explained by difference in population studied and the availability of allergy medications such as cetirizine (Zyrtec®) without a prescription, which was not the case when this prior study was completed. We also found a high use of cardiovascular drugs, such as antihypertensives, and know of only one other author who found similar results, though that study was not conducted in the United States.21

Convenience was the most frequently cited reason for medication borrowing, and a family member or friend was the most common source, rather than more traditionally thought of routes of diversion such as theft, the internet, and/or via a street dealer. This implies that individuals are primarily obtaining medications from easily accessed and highly trusted sources, especially when their usual medical providers are not easily accessible. Our findings also correlate with other studies which found a low rate of obtaining medications through the internet.22 Though many factors may determine a patient’s access to care, our study population’s high level of connectivity to a primary medical provider was not sufficient to avoid medication borrowing. That a provider’s inquiry into medication use impacted on medication borrowing is intriguing; an underlying rationale for why a cause and effect exists is unclear and may represent an interesting topic for additional research. Additionally, only a third of patients who borrowed medications reported it to their medical provider, which may demonstrate a degree of realization that what they did was inappropriate or careless. Conversely it may represent a lack of recognition of the potential dangers associated with taking medications without a provider’s prescription or knowledgeable advice.

There are several potential limitations in this study. Since we intentionally examined a predominantly adult population seeking medical care at an urban medical center, our results may not be generalized to more diverse populations. We believe that data regarding this population will be valuable to medical providers, especially those who practice in disadvantaged urban areas. Second, by choosing a cross-sectional study design, our ability to draw cause and effect conclusions are limited. Therefore, we submit our findings as associations and suggest they be used for future study of direct impact. This is exemplified by our finding that Medicare insurance was associated with a lower rate of borrowing. Though this may reflect the previously stated finding that older patients borrow less frequently, our results did not reproduce this impact of age which suggests that other factors may contribute and additional studies are needed to clarify this. Third, though the prevalence of medication borrowing was comparable to past studies of a national scope, social desirability bias (the tendency of respondents to reply in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others) may have resulted in under-reporting, and thus our results may actually underestimate the true prevalence of medication borrowing in the study population.23 Lastly, by relying on self reports of behavior, our findings are limited by recall bias, as well as by participants’ understanding of the questions in the survey.

Our study has several important implications, chief among them is that in an adult urban-based population seeking medical care, the prevalence of medication borrowing was significant, nearly one in every five patients. Our study results are of particular importance to medical professionals by providing insight into the prevalence of medication borrowing within an adult urban population seeking medical care. That such a significant proportion of our respondents borrowed medications has potential implications for how medical providers take a patient’s medication history, or prescribe medications since in any given day, several of their patients may have borrowed a medication and not told them about it during their office visit. Medical providers should regularly inquire about medication use, and consider cautioning patients about medication borrowing, even if they deny the behavior. Future studies should examine the reasons behind borrowing medications for nonacute indications such as hypertension and how provider behaviors and insurance status may impact on the rate of medication borrowing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Heather Hammer, Dr. Xiang Liu, and Sandeep Chennadi for their assistance with the statistical analysis, as well as Meredith Majczan, PharmD and Ben Wu, PharmD for their assistance with survey administration. This research was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Health, obtained through the Temple University Center for Minority Health Studies. This research has been previously presented as an abstract during the 2009 Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in Miami, FL. The Institutional Review Board of the Temple University School of Medicine approved this project.

Financial support Temple University Center for Minority Health Studies

Appendix

Survey instrument. See next page.

Temple University Prescription Drug Use Survey

Thank you for taking the time to participate in our research study. We are trying to learn more about what medications people are taking and why. It should take you no more than 5 to 10 min to complete this questionnaire. When you finish your completed questionnaire, you will receive a Septa token as a thank you for your help.

There are some questions that ask about subjects or actions that may not be comfortable for you to share. Please understand that this survey is completely anonymous and confidential—meaning that there is no way to identify you and your answers will not be shared with anyone apart from the study team. No one outside of our project team will have access to your answers. Try to answer honestly and accurately as possible.

Any reports created as a result of the questionnaire will be reported as a group, once again so that no one will identify you personally. You may choose not to answer any question that you want.

Preamble

Contributor Information

Lawrence Ward, Phone: +1-215-7070712, FAX: +1-215-2268245, Email: lawrence.ward@tuhs.temple.edu.

Nima M. Patel, Phone: +1-215-7072319, Email: nmpatel@temple.edu

References

- 1.Public Law: Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987. Pul. L No. 100–293, 102 Stat. 95 342 (Apr. 22, 1988). Available at: http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFoodDrugandCosmeticActFDCAct/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/PrescriptionDrugMarketingActof1987/ucm201702.htm. Accessed on: May 10, 2011.

- 2.Goldsworthy RC, Schwartz NC, Mayhorn CB. Beyond abuse and exposure: framing the impact of prescription-medication sharing. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1115–1121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grzybowski S. The black market in prescription drugs. Med Crime Punishment. 2004;364:28–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17630-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coben JH, Davis SM, Furbee PM, Sikora RD, Tillotson RD, Bossarte RM. Hospitalizations for poisoning by prescription opioids, sedatives, and tranquilizers. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forgione DA, Neuenschwander P, Vermeer TE. Diversion of prescription to the black market: what the states are doing to curb the tide. Health Care Finance. 2001;27:65–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613–2620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen EE, Rasmussen SA, Daniel KL, et al. Prescription medication borrowing and sharing among women of reproductive age. J Womens Health. 2008;17(7):1073–1080. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, et al. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):21–31. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garnier LM, Arria AM, Caldiera KM, Vincent KB, O’Grady KE, Wish ED. Sharing and selling of prescription medications in a college student sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:262–269. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05189ecr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldsworthy RC, Mayhorn CB. Prescription medication sharing among adolescents: prevalence, risks, and outcomes. J Adolescent Health. 2009;6:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniel KL, Honein MA, Moore CA. Sharing prescription medication among teenage girls: potential danger to unplanned/undiagnosed pregnancies. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1167–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson EL, Dilone J, Garcia M, Smolowitz J. Factors which influence latino community members to self-prescribe antibiotics. Nurs Res. 2006;55(2):94–102. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell L, Kochbar K, Saywell, et al. Use of herbal remedies by hispanic patients: do they inform their physician? J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:566–578. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiscella K, Williams DR. Health disparities based on socioeconomic inequities: implications for urban health care. Acad Med. 2004;79:1139–1147. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reijneveld SA. The impact of individual and area characteristics on urban socioeconomic differences in health and smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:33–40. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galea S, Vlahov D. Urban health: evidence, challenges, and directions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:341–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings. Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUHlatest.htm. Accessed on: March 30, 2010.

- 19.Starrels JL, Barg FK, Metlay JP. Patterns and determinants of inappropriate antibiotic use in injection drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):263–269. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0859-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richman PB, Garra G, Eskin B, Nashed AH, Cody R. Oral antibiotic use without consulting a physician: a survey of ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:57–60. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorensen L, King MA, Ientile CS, Roberts MS. Has drug therapy gone to the dogs? Age Ageing. 2003;32:460–461. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Kurtz SP, Martin SS, Parrino MW. The “Black Box” of prescription drug diversion. J Addict Dis. 2009;28:332–347. doi: 10.1080/10550880903182986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holbrook L, Green MC, Krosnick JA. Telephone versus face-to-face interviewing of national probability samples with long questionnaires: comparisons of respondent satisficing and social desirability response bias. Public Opin Q. 2003;67:79–125. doi: 10.1086/346010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]