Abstract

Arsenic is a ubiquitous contaminant in drinking water. Whereas arsenic can be directly hepatotoxic, the concentrations/doses required are generally higher than present in the US water supply. However, physiological/biochemical changes that are alone pathologically inert can enhance the hepatotoxic response to a subsequent stimulus. Such a '2-hit' paradigm is best exemplified in chronic fatty liver diseases. Here, the hypothesis that low arsenic exposure sensitizes liver to hepatotoxicity in a mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease was tested. Accordingly, male C57Bl/6J mice were exposed to low fat diet (LFD; 13% calories as fat) or high fat diet (HFD; 42% calories as fat) and tap water or arsenic (4.9 ppm as sodium arsenite) for ten weeks. Biochemical and histologic indices of liver damage were determined. High fat diet (± arsenic) significantly increased body weight gain in mice compared with low-fat controls. HFD significantly increased liver to body weight ratios; this variable was unaffected by arsenic exposure. HFD caused steatohepatitis, as indicated by histological assessment and by increases in plasma ALT and AST. Although arsenic exposure had no effect on indices of liver damage in LFD-fed animals, it significantly increased the liver damage caused by HFD. This effect of arsenic correlated with enhanced inflammation and fibrin extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. These data indicate that subhepatotoxic arsenic exposure enhances the toxicity of HFD. These results also suggest that arsenic exposure might be a risk factor for the development of fatty liver disease in human populations.

Keywords: sodium arsenite, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity

Inorganic arsenic is a ubiquitous element and a natural drinking water contaminant (National Research Council, 1999; 2001). Owing to its toxic potential to humans, it is a high priority hazardous substance in the United States. Chronic exposure to arsenic has been linked with a myriad of possible health effects, including skin lesions, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and malignancies of the skin and internal organs (Waalkes et al., 2004). The liver is a well-known target organ of arsenic exposure. Hepatic abnormalities caused by arsenic exposure include hepatomegaly, non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis and portal hypertension (Santra et al., 1999; 2000; Mazumder, 2005). Furthermore, arsenic exposure has been linked to hepatic malignancies, namely hepatic angiosarcoma and hepatocellular carcinoma in both humans and in animal models (Smith et al., 1992; Waalkes et al., 2006). Straub et al. (2007) demonstrated that mouse liver is also sensitive to more subtle hepatic changes (e.g., hepatic endothelial cell capillarization and vessel remodeling) at lower arsenic exposure levels (250 ppb) without any gross pathologic effects. It is nevertheless unclear at this time if environmental arsenic exposure at the levels observed in the US causes liver disease.

Another major health concern for the US population is obesity, the prevalence of which is increasing at an alarming rate (Flegal et al., 1998; Ogden et al., 2006). Among the myriad of health complications associated with obesity (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular risk, etc.) is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The moniker “non-alcoholic” is derived from the fact that the pathology of NAFLD is indistinguishable from that of alcoholic fatty liver disease, but occurs in the absence of significant alcohol consumption (Ludwig et al., 1980). NAFLD is a spectrum of liver diseases, ranging from simple steatosis, to active inflammation, to advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis (Day, 2006). Risk factors for primary NAFLD (i.e., not secondary to other proximate causes) are analogous to those of metabolic syndrome (e.g., obesity, type II diabetes, and dyslipidemia(Clark, 2006). It is however also clear that there are likely other unidentified risk factors that contribute to the development of disease.

A striking feature of arsenic exposure and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is that there is significant overlap between areas of risk in the US (Welch et al., 2000; Mokdad et al., 2003). For example, states with clusters of municipal wells with high levels of arsenic [e.g., Michigan, Texas, West Virginia, and Oklahoma (United States Geological Survey, 2007)] also have high incidences of obesity and diabetes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Furthermore, high arsenic in the drinking water is generally localized to private artesian water supplies (not regulated by the EPA) in rural communities, where the incidence of obesity tends to be even higher than in most areas of the country (National Center for Health Statistics, 2001). It is therefore possible that arsenic exposure is an unidentified environmental risk factor in the development of NAFLD. The purpose of the current study was to test the hypothesis that low dose arsenic exposure sensitizes liver to hepatotoxicity in a mouse model of NAFLD.

Methods

Animals and Treatments

Four week old male C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and procedures were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Food and tap water were allowed ad libitum. Mice were fed AIN-76A Purified diet (Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI) for one week to reduce potential confounding factors of arsenic present in standard laboratory chow (Kozul et al., 2008). Mice were exposed to sodium arsenite (4.9 ppm in drinking water) or tap water for one week prior to initiating feeding with either low fat diet (13% fat in calories) or high fat diet (42% fat in calories) (Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI) for 10 weeks. This exposure level of arsenic was determined by preliminary range-finding experiments to cause no overt liver damage in mice fed low-fat diet. Food and water consumption were measured twice a week. Body weight was measured once a week. For sacrifice, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100/15 mg/kg i.m.). Blood was collected from the vena cava just prior to sacrifice by exsanguination, and citrated plasma was stored at −80°C for further analysis. Portions of liver tissue were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, while others were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin or embedded in frozen specimen medium (Tissue-Tek OCT compound, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) for subsequent sectioning and mounting on microscope slides.

Clinical analyses and histology

Plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), triglycerides (TG), cholesterol (CHOL), albumin and total protein were determined using standard kits (Thermo Scientific, Middletown, VA). Plasma levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL) and low density lipoprotein (LDL) were determined using kits (Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA). Hepatic lipids were extracted and determined as previously described (Bergheim et al., 2006; Kaiser et al., 2009). Plasma insulin (fed) was quantified using an ELISA kit purchased from ALPCO Diagnostics (Windham, NH) (Beier et al., 2008). Plasma levels of glucose (fed) were determined using a glucose assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA) (Beier et al., 2008).

Immunostainining

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm) were deparaffinized and then rehydrated with graded ethanol solutions. Slides were incubated in primary antibody for F4/80 cell surface receptor (Abcam plc, Cambridge, MA). A secondary antibody, biotinylated anti-Rat IgG was used (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). Immunohistochemistry was visualized using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Metamorph software. Immunofluorescent detection of fibrin deposition was carried out as described previously (Beier et al., 2009).

RNA Isolation and Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissue samples by a guanidium thiocyanate-based method (Tel-Test, Austin, TX). RNA concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically, and 1 µg total RNA was reverse transcribed using a kit (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD). PCR was performed using the ABI StepOne Plus Software. The comparative CT method was used to determine fold differences between samples. The comparative CT method determines the amount of target, normalized to an endogenous reference (β-actin) and relative to a calibrator (2−ΔΔCt).

Statistical analyses

Results are reported as means ± SE (n = 6–10). ANOVA with Bonferronis post-hoc test (for parametric data) or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test (for nonparametric data) for the determination of statistical significance among treatment groups, as appropriate. A p value less than 0.05 was selected before the study as the level of significance.

Results

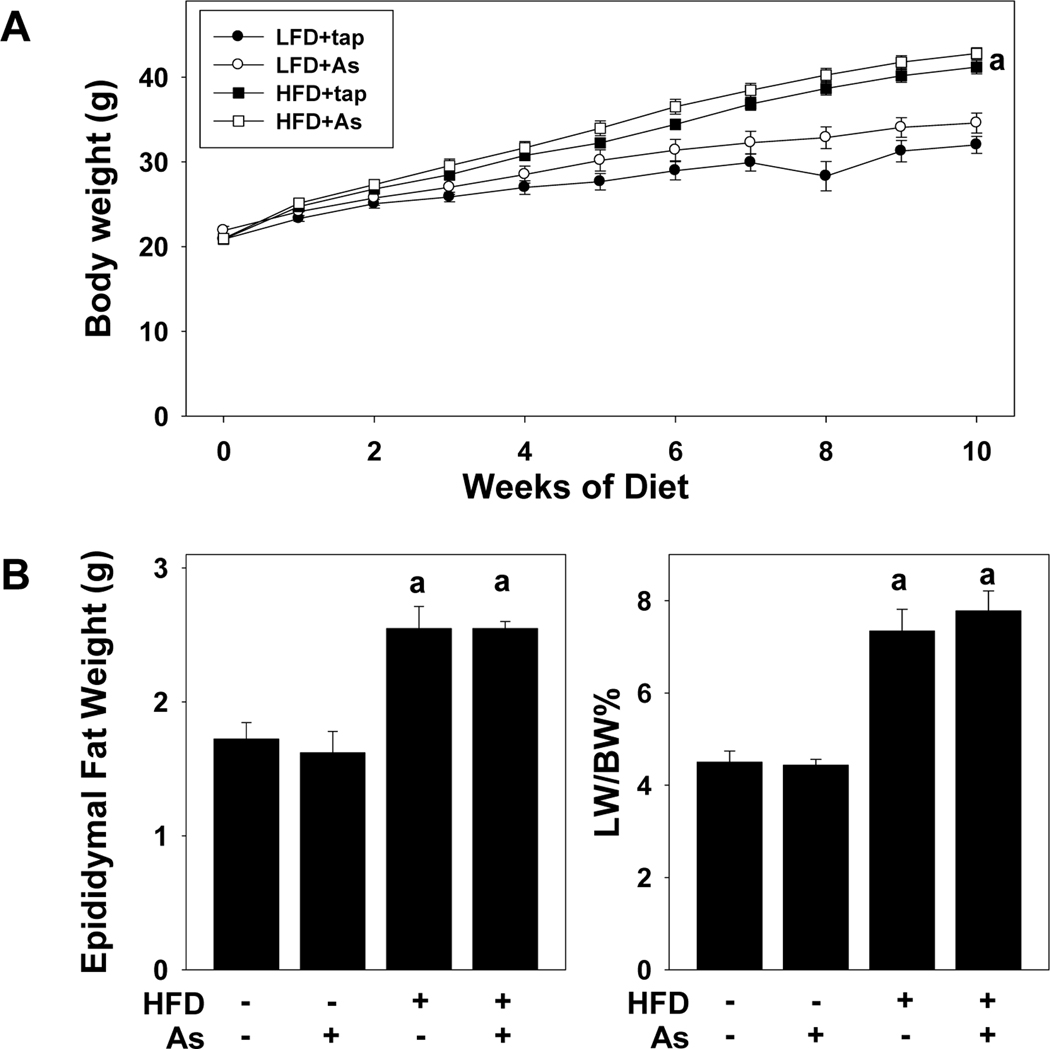

Effect of HFD and arsenic on body and organ weight

All animals gained weight during the course of the study and there was no mortality or morbidity in any group during the course of the study. Mice fed LFD+tap water consumed an average of 3.0±0.1 g/d over the course of the study. Mice fed HFD+tap water consumed ~25% more food, with values of 3.8±0.2 g/d. Arsenic exposure did not significantly affect food consumption in either diet group, with values of 2.9±0.1 g/d and 3.4±0.2 g/d, for LFD and HFD, respectively. Mice fed HFD also gained weight at a significantly more rapid rate (Figure 1A); differences in final average weights between HFD and LFD were ~10 g; arsenic did not significantly alter the effect of HFD on this variable. This increase in body weight caused by HFD was accompanied by a corresponding increase in fat deposition, as indicated by a ~50% increase in the weight of the epididymal fat pads at sacrifice (Figure 1B). Likewise, HFD feeding caused hepatomegaly, as indicated by the almost doubling of liver size in the HFD groups (Figure 1C). The effect of HFD on fat deposition (Figure 1B) and liver size (Figure 1C) and was unaltered by arsenic exposure.

Figure 1. Effect of high fat diet on growth and organ weight.

Body weight over time (A), epididymal fat pad weight (B) and liver weight (C) for tap water or arsenic exposed mice fed with low fat or high fat diet for 10 weeks are shown. Data are means ± SEM (n = 6–10). a, p < 0.05 compared to low fat diet.

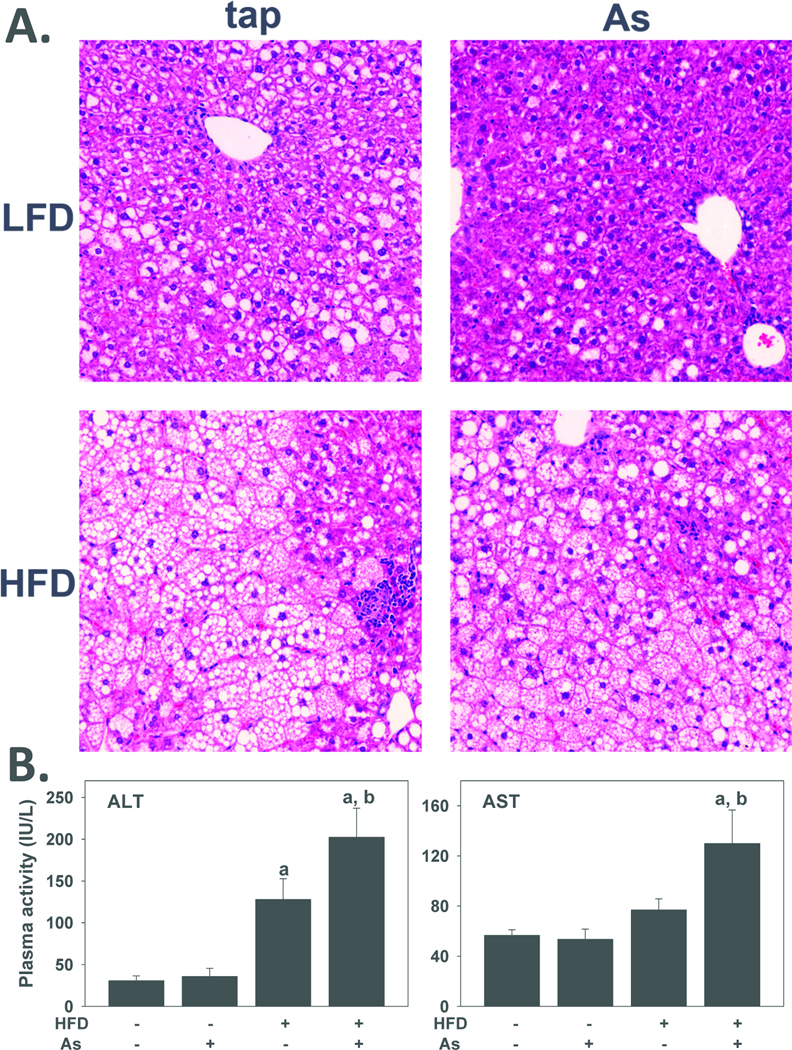

Arsenic exposure enhanced HFD-induced liver injury

Previous studies have shown that feeding mice a diet enriched in triglycerides and cholesterol (i.e., 'Western diet') causes obesity, insulin resistance and fatty liver injury [e.g., (Wouters et al., 2008)], with pathology similar to that found in human non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). As expected by the hepatomegaly observed (Figure 1C), 10 weeks of HFD feeding dramatically increased lipid accumulation in the liver (steatosis; Figure 2A, lower left panel); this pathologic change comprised both macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis. HFD feeding also increased the appearance of necroinflammatory foci in the liver. This dietary exposure significantly increased plasma activity of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ~5-fold. Exposure to arsenic did not significantly affect the macroscopic histology or plasma transaminase values in LFD-fed mice. There were no apparent gross morphologic changes in livers from HFD+arsenic (Figure 2A, lower right panel) in comparison to the HFD+tap group. In contrast, both ALT and AST activities in the plasma of HFD+arsenic were significantly higher than those exposed to tap (Figure 2B), indicative of more liver injury.

Figure 2. Effect of high fat diet and arsenic on liver injury.

A: Representative photomicrographs (200×) depicting hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) stains are shown. B: Plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in tap water or arsenic exposed mice after 10 weeks of diet feeding are shown. Quantitative data are means ±SE> (n = 6–10). a, p < 0.05 compared to low fat diet. b, p < 0.05 compared to tap.

Arsenic exposure did not alter changes in plasma insulin or glucose, or fatty liver caused by HFD feeding

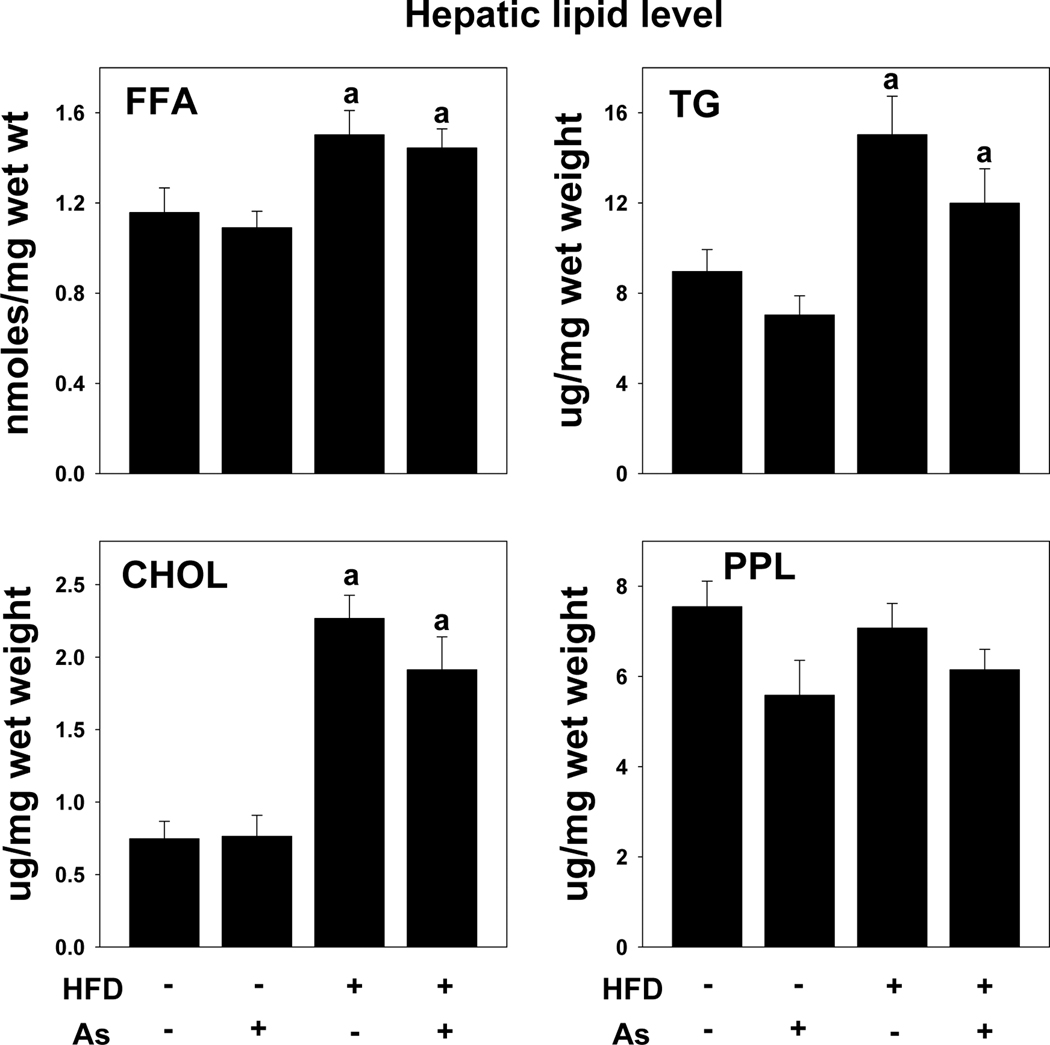

Feeding HFD to rodents or humans is known to increase blood glucose, which is indicative of impaired insulin signaling. Arsenic exposure had no significant effect on plasma glucose or insulin in LFD-fed mice (Table 1). HFD feeding in tap-exposed animals increased plasma glucose levels significantly, although insulin levels remained the same (Table 1); the addition of arsenic to the drinking water did not significantly alter plasma glucose or insulin compared to the HFD+tap group. As expected from the histologic changes (see Figure 2A), HFD feeding significantly increased the levels of FFA (~1.4-fold), TG (~2-fold), and cholesterol (~3-fold) in the liver (Figure 3). Hepatic content of phospholipids was not altered by high fat diet feeding. Arsenic exposure did not significantly change the effect of HFD on any of these variables. Plasma levels of cholesterol, HDL and LDL were also significantly increased by HFD feeding (Table 1). None of these variables were significantly affected by arsenic coexposure.

Table 1. Effect of high fat diet and arsenic on plasma profiles.

Animals were fed with low fat or high fat diet for 10 weeks with either tap or arsenic water as described in Methods. Plasma levels of glucose, insulin, lipids, albumin and total protein were measured.

| Plasma profile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low fat diet | High fat diet | |||

| tap water | arsenic water | tap water | arsenic water | |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 315 ± 31 | 349 ± 23 | 520 ± 45a | 460 ± 44a |

| Insulin (ng/dl) | 68 ± 19 | 52 ± 11 | 63 ± 10 | 68 ± 15 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 106 ± 4. | 115 ± 8 | 222± 21a | 180 ± 8a |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 31 ± 2 | 36 ± 3 | 38 ± 6 | 28 ± 6 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 97 ± 4 | 91 ± 5 | 121 ± 6a | 134 ± 8a |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 15 ± 2 | 16 ± 3 | 27± 3a | 30± 2a |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.1 |

Data are mean ± SE (n=5–8).

p < 0.05 compared to low fat diet.

Abbreviations: high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL).

Figure 3. Effect of high fat diet and arsenic on hepatic lipids.

Hepatic levels of free fatty acids (FFA), triglycerides (TG), cholesterol (CHOL) and phospholipids (PPL) in mice exposed to tap water or arsenic water after 10 weeks of low fat or high fat feeding are shown. Data are means ±SEM (n = 6–10). a, p < 0.05 compared to low fat diet.

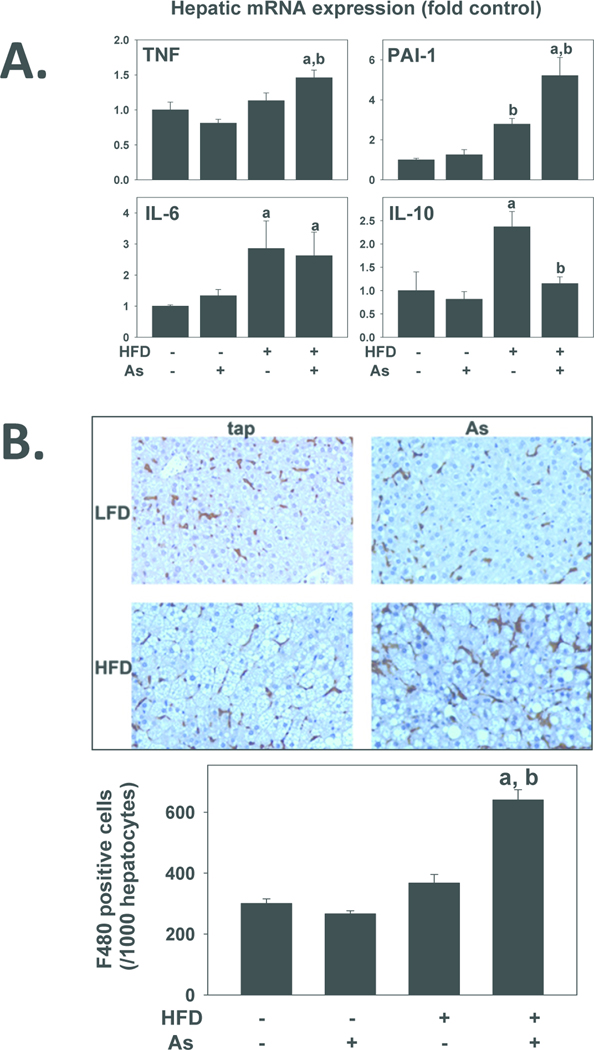

Effects of high fat diet and arsenic on hepatic inflammation

Previous work by this group showed that arsenic preexposure enhances the hepatic inflammatory response to bacterial LPS (Arteel et al., 2008). The exacerbated liver damage caused by arsenic coexposure to HFD-fed mice could also be mediated by elevated inflammation. Therefore, the effect of HFD and arsenic on indices of hepatic inflammation were determined (Figure 4). Ten weeks of HFD significantly increased hepatic mRNA expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1; ~3-fold), IL-6 (~3-fold) and IL-10 (~2.5-fold) (Figure 4A). Arsenic exposure had no effect on expression of any of these genes in mice fed LFD. In mice fed with HFD, arsenic exposure significantly increased TNFα expression, and enhanced the effect of HFD on PAI-1 expression. The increase in IL-10 expression caused by HFD was significantly attenuated by arsenic coexposure. The expresion of IL-6 was unaffected by arsenic exposure. Although it had no effect on this variable in the LFD group, arsenic coexposure significantly increased the number of F4/80-positive cells in the HFD group (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Effect of high fat diet and arsenic on hepatic inflammation.

A: Effect of high fat diet and arsenic on hepatic mRNA expressions of tissue necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) are shown. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described in Methods. B: Representative photomicrographs (200×; upper panel) and quantitation (lower panel) of F4/80 immunostains are shown. Quantitative data are means ± SE (n = 6–10) and are expressed as fold of control. a, p < 0.05 compared to low fat diet. . b, p < 0.05 compared to tap.

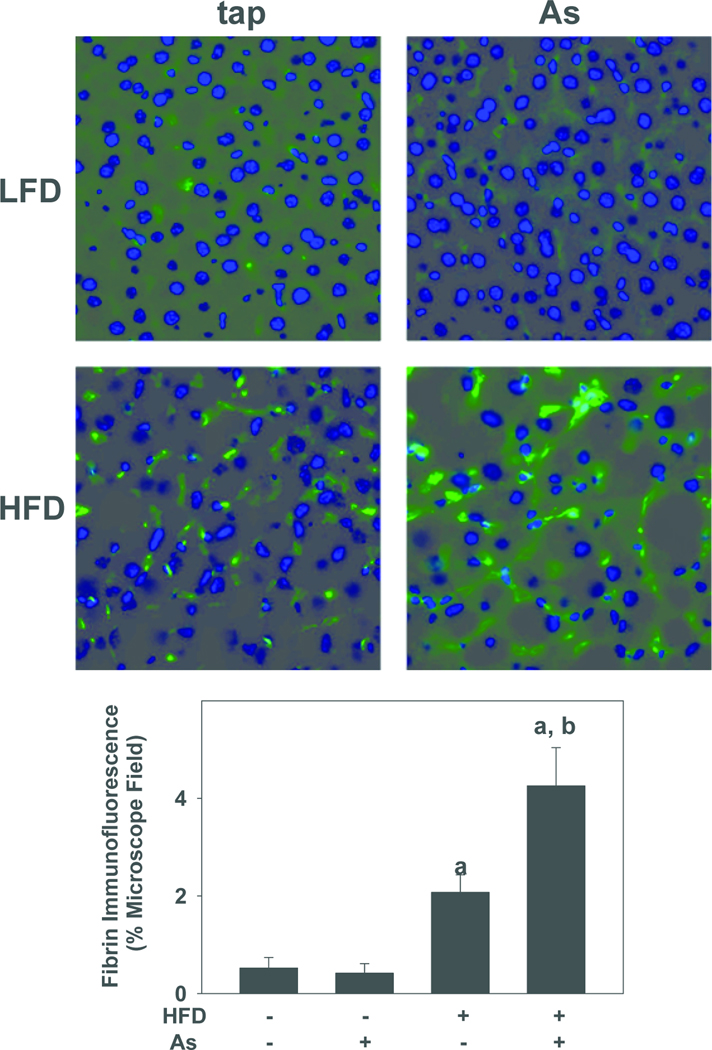

PAI-1 is a major inhibitor of both tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), and is therefore a key regulator of fibrin degradation (i.e., fibrinolysis) by plasmin (Kruithof, 1988). The effect of HFD and arsenic exposure on fibrin extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation in liver was therefore determined by immunofluorescence (Figure 5). Low-level fibrin ECM was detected in the perisinusoidal areas of livers from LFD+tap mice (Figure 5); arsenic coexposure did not significantly increase the extent of fibrin staining in this dietary group (Figure 5). HFD alone significantly increased fibrin deposition ~4-fold in comparison with LFD controls; arsenic significantly enhanced fibrin staining caused by HFD by ~2-fold.

Figure 5. Effect of high fat diet and arsenic on fibrin deposition.

Representative photomicrographs (200×; upper panel) and quantitation (lower panel) of fibrin immunofluorescence (green color) are shown. Quantitative data are means ± SE (n = 6–10) and are expressed as fold of control. a, p < 0.05 compared to low fat diet. . b, p < 0.05 compared to tap.

Arsenic did not enhance hepatic fibrosis

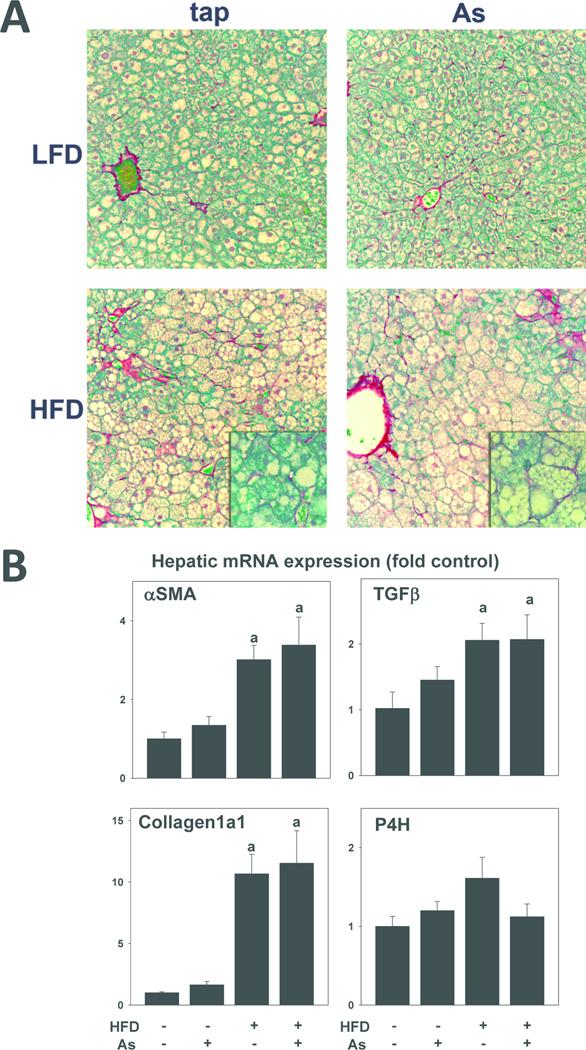

Fibrosis is a common pathologic response to chronic hepatic injury. The effect of HFD feeding and arsenic exposure on indices of hepatic fibrosis and fibrogenesis were therefore determined (Figure 6). HFD feeding for 10 weeks caused perisinusoidal fibrosis in liver, as determined by Sirius red staining (Figure 6A, lower left panel). Coexposure of arsenic in the drinking water did not alter this effect of HFD (Figure 6A, lower right panel). Increases in the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), TGFβ, and collagen Iα1 are indicative of stellate cell activation and increased ECM synthesis in liver. The effect of HFD and arsenic on hepatic expression of these genes was therefore determined (Figure 6B). HFD diet feeding for 10 weeks significantly increased expression of all 3 of these genes; arsenic coexposure did not significantly affect expression in either LFD- or HFD-fed mice (Figure 6B). The expression of prolyl-4-hydroxylase (α subunit), a component of the enzyme responsible for crosslinking of collagen fibrils, was unaffected by either diet or arsenic under these conditions (Figure 6B, lower right panel).

Figure 6. Effect of high fat diet and arsenic on hepatic fibrosis.

A: Representative photomicrographs (200×) of Sirius Red stains with 400× insets are shown. B: Effects of high fat diet and arsenic on hepatic mRNA expressions of alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), Collagen1a1 and prolyl-4-hydroxylase (P4H) are shown. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described in Methods. Quantitative data are means ± SE (n = 6–10) and are expressed as fold of control. a, p < 0.05 compared to low fat diet. b, p < 0.05 compared to tap.

Discussion

Nearly 4,000 wells providing community water in the U.S. have arsenic levels greater than the current WHO recommended maximum contaminant level (MCL) of 10 µg/L (Engel et al., 1994; Frost et al., 2003). Furthermore, even higher arsenic concentrations may be found in private artesian water supplies not regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act. As mentioned in the Introduction, although the liver is a known target organ of chronic arsenic exposure, such effects are observed primarily in regions of the world with arsenic concentrations in the drinking water that are much higher than generally observed in the US [e.g., Bangladesh (Santra et al., 1999)]. Therefore, whether or not the concentrations/doses required to achieve significant hepatotoxicity are relevant to US exposure levels is unclear.

Previous work by this group has shown that arsenic exposure, at concentrations that aren't overtly hepatotoxic, enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice (Arteel et al., 2008). Numerous studies have now established that physiological/biochemical changes to liver that are pathologically inert can enhance the hepatotoxic response caused by a second agent; this ‘2-hit’ paradigm has been best exemplified in fatty liver diseases (Day et al., 1998). For example, Yang et al. (1997) demonstrated that livers from genetically obese (fa/fa) rats are exquisitely sensitive to hepatotoxicity caused by the injection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) compared to their lean littermates; this exacerbation of liver damage was characterized by a more robust inflammatory response and enhanced cell death. A similar effect was observed in the response to LPS after arsenic exposure (Arteel et al., 2008). It was therefore hypothesized here that subhepatotoxic arsenic exposure would enhance liver damage caused by high-fat diet in mice, which resembles NAFLD.

Hepatic changes caused by arsenic exposure include altered lipid metabolism, steatosis, enhanced inflammation and fibrosis (Santra et al., 2000; Mazumder, 2005). Similar changes are involved in the development and progression of NAFLD (Choi et al., 2005; Diehl et al., 2005) Furthermore, arsenic may increase the risk of developing type II diabetes in humans (Navas-Acien et al., 2009), which is a known risk factor for NAFLD (Clark, 2006). Indeed, recent work has shown in experimental animals that arsenic enhances insulin resistance caused by HFD in mice (Paul et al., 2011). The effect of arsenic and LPS on indices of these potential mechanisms was therefore determined. Arsenic did not alter hepatic or plasma lipid profiles, neither in the LFD or HFD groups (Figures 2 and 3; Table 1) indicating that the enhancement of HFD-induced liver damage by arsenic is not via increased steatosis. Likewise, arsenic did not alter the increase in plasma fed glucose caused by HFD in mice (Table 1). Lastly, arsenic exposure had no apparent effect on the increase in indices of fibrosis caused by HFD in this study (Figure 6). In contrast to steatosis, glucose levels and fibrosis, arsenic exposure did enhance increases in indices of inflammation caused by HFD (Figure 4). Specifically, arsenic increased the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα in the HFD group. Furthermore, arsenic blunted the increase in expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 in the HFD group. It is proposed that the imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines is a critical step in NAFLD (Tilg, 2010). Arsenic also increased the number of activated macrophages, as determined by F4/80 staining (Figure 4B). Taken together, these results suggest that arsenic enhanced liver damage caused by HFD by increasing the inflammatory response.

Arsenic also significantly enhanced expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in HFD-fed mice. This effect correlated with an increase in perisinusoidal deposition of fibrin ECM in the liver (Figure 5). Previous work by this group and others have shown a correlation between fibrin ECM and inflammation in models of hepatic injury [e.g., (Bergheim et al., 2005; 2006; Beier et al., 2009]. There are several potential mechanisms by which fibrin ECM is proinflammatory. For example, fibrin clots disrupt the flow of blood within the hepatic parenchyma (i.e., hemostasis); the subsequent microregional hypoxia and hepatocellular death may directly and indirectly increase a proinflammatory response (Hewett et al., 1995; Wanless et al., 1995; Pearson et al., 1996; Ganey et al., 2004). Furthermore, fibrin matrices have been shown to be permissive to chemotaxis and activation of monocytes and leukocytes (Holdsworth et al., 1979; Loike et al., 1995). Therefore, the increase in PAI-1 caused by arsenic exposure in the HFD group could contribute to hepatic inflammation by enhancing fibrin ECM deposition.

There are significant differences between the absorption and elimination of arsenic between rodents and humans, making direct comparison of exposure levels difficult between the species; for example, exposure of rodents to 50 ppm arsenic resulted in plasma levels that were only ~10-fold higher than humans consuming 50–100 ppb (Hall et al., 2006). Nevertheless, the exposure level (4.9 ppm) of arsenic used in this study, while in the range of published rodent studies [e.g., (Santra et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2004)], is still high relative to human exposure in the US (ppb). Furthermore, although arsenic appeared to enhance liver damage caused by HFD under these conditions, too few concentrations were employed to determine the nature of this potential interaction (e.g., additive, synergistic, etc). Therefore, although these results serve as proof-of-concept of the potential interaction between arsenic and other hepatoxicants, future studies are required to validate these findings with lower exposures of arsenic in more chronic models of liver diseases.

Summary and Conclusions

There are many gaps in our understanding of the relative safety of arsenic to the human population. Importantly, most studies to date have focused on the effect of arsenic alone and not taken into consideration risk-modifying factors. Furthermore, even fewer studies have tested the possibility that arsenic may be a risk modifying factor for other diseases. It was shown here that arsenic enhances experimental NAFLD in mice. Although the increase in liver injury caused by arsenic under these conditions, NAFLD is a chronic disease that requires several years to progress (Adams et al., 2005), so relatively small changes can be greatly amplified over time. These results therefore suggest that the relative risk of hepatic damage caused by arsenic exposure may have to be modified to take into account other mitigating factors, such as underlying fatty liver disease.

Highlights.

Characterizes a mouse model of arsenic enhanced NAFLD.

Arsenic synergistically enhances experimental fatty liver disease at concentrations that cause no overt heptotoxicity alone

This effect is associated with increased inflammation

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by a grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES016367, ES015812 and ES014443). JIB was supported by a postdoctoral (T32) fellowship from National Institute of Environmental Health Science (ES011564).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:113–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arteel GE, Guo L, Schlierf T, Beier JI, Kaiser JP, Chen TS, Liu M, Conklin DJ, Miller HL, von Montfort C, States JC. Subhepatotoxic exposure to arsenic enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol.Appl.Pharmacol. 2008;226:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beier JI, Guo L, von Montfort C, Kaiser JP, Joshi-Barve S, Arteel GE. New role of resistin in lipopolysaccharide-induced liver damage in mice. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 2008;325:801–808. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.136721.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beier JI, Luyendyk JP, Guo L, von Montfort C, Staunton DE, Arteel GE. Fibrin accumulation plays a critical role in the sensitization to lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury caused by ethanol in mice. Hepatology. 2009;49:1545–1553. doi: 10.1002/hep.22847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergheim I, Guo L, Davis MA, Lambert JC, Beier JI, Duveau I, Luyendyk JP, Roth RA, Arteel GE. Metformin prevents alcohol-induced liver injury in the mouse: Critical role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2099–2112. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergheim I, Luyendyk JP, Steele C, Russell GK, Guo L, Roth RA, Arteel GE. Metformin prevents endotoxin-induced liver injury after partial hepatectomy. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 2005;316:1053–1061. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: turning information into action. 2007 http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. 2-5-2007.

- 8.Choi S, Diehl AM. Role of inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr.Opin.Gastroenterol. 2005;21:702–707. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000182863.96421.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J.Clin.Gastroenterol. 2006;40:S5–S10. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000168638.84840.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day CP. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: current concepts and management strategies. Clin.Med. 2006;6:19–25. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two "hits"? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diehl AM, Li ZP, Lin HZ, Yang SQ. Cytokines and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2005;54:303–306. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel RR, Smith AH. Arsenic in drinking water and mortality from vascular disease: an ecologic analysis in 30 counties in the United States. Arch.Environ.Health. 1994;49:418–427. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9954996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends 1960–1994. Int.J.Obes.Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frost FJ, Muller T, Petersen HV, Thomson B, Tollestrup K. Identifying US populations for the study of health effects related to drinking water arsenic. J.Expo.Anal.Environ.Epidemiol. 2003;13:231–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganey PE, Luyendyk JP, Maddox JF, Roth RA. Adverse hepatic drug reactions: inflammatory episodes as consequence and contributor. Chem.Biol.Interact. 2004;150:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hewett JA, Roth RA. The coagulation system, but not circulating fibrinogen, contributes to liver injury in rats exposed to lipopolysaccharide from gram-negative bacteria. The Journal of Pharmacological and Experimental Therapeutics. 1995;272:53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holdsworth SR, Thomson NM, Glasgow EF, Atkins RC. The effect of defibrination on macrophage participation in rabbit nephrotoxic nephritis: studies using glomerular culture and electronmicroscopy. Clin.Exp.Immunol. 1979;37:38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser JP, Beier JI, Zhang J, David HJ, von Montfort C, Guo L, Zheng Y, Monia BP, Bhatnagar A, Arteel GE. PKCepsilon plays a causal role in acute ethanol-induced steatosis. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2009;482:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozul CD, Nomikos AP, Hampton TH, Warnke LA, Gosse JA, Davey JC, Thorpe JE, Jackson BP, Ihnat MA, Hamilton JW. Laboratory diet profoundly alters gene expression and confounds genomic analysis in mouse liver and lung. Chem.Biol.Interact. 2008;173:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kruithof EK. Plasminogen activator inhibitors--a review. Enzyme. 1988;40:113–121. doi: 10.1159/000469153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loike JD, el Khoury J, Cao L, Richards CP, Rascoff H, Mandeville JT, Maxfield FR, Silverstein SC. Fibrin regulates neutrophil migration in response to interleukin 8, leukotriene B4, tumor necrosis factor, and formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1995;181:1763–1772. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin.Proc. 1980;55:434–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazumder DN. Effect of chronic intake of arsenic-contaminated water on liver. Toxicol.Appl.Pharmacol. 2005;206:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Health, United States, 2001, with Urban and Rural Health Chart Book. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Research Council. Arsenic in drinking water. Washington, DC: National academy press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Research Council. Arsenic in drinking water: 2001 update. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navas-Acien A, Silbergeld EK, Pastor-Barriuso R, Guallar E. Rejoinder: Arsenic exposure and prevalence of type 2 diabetes: updated findings from the National Health Nutrition and Examination Survey, 2003–2006. Epidemiology. 2009;20:816–820. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181afef88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul DS, Walton FS, Saunders RJ, Styblo M. Characterization of the impaired glucose homeostasis produced in C57BL/6 mice by chronic exposure to arsenic and high-fat diet. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119:1104–1109. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson JM, Schultze AE, Schwartz KA, Scott MA, Davis JM, Roth RA. The thrombin inhibitor, hirudin, attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in the rat. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 1996;278:378–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santra A, Das GJ, De BK, Roy B, Guha Mazumder DN. Hepatic manifestations in chronic arsenic toxicity. Indian J.Gastroenterol. 1999;18:152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santra A, Maiti A, Das S, Lahiri S, Charkaborty SK, Mazumder DN. Hepatic damage caused by chronic arsenic toxicity in experimental animals. J.Toxicol.Clin.Toxicol. 2000;38:395–405. doi: 10.1081/clt-100100949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith AH, Hopenhayn-Rich C, Bates MN, Goeden HM, Hertz-Picciotto I, Duggan HM, Wood R, Kosnett MJ, Smith MT. Cancer risks from arsenic in drinking water. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1992;97:259–267. 259–267. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9297259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straub AC, Stolz DB, Ross MA, Hernandez-Zavala A, Soucy NV, Klei LR, Barchowsky A. Arsenic stimulates sinusoidal endothelial cell capillarization and vessel remodeling in mouse liver. Hepatology. 2007;45:205–212. doi: 10.1002/hep.21444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tilg H. The role of cytokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig.Dis. 2010;28:179–185. doi: 10.1159/000282083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.United States Geological Survey. Arsenic in ground water of the United States. 2007 http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/trace/arsenic/. 2-7-2007.

- 39.Waalkes MP, Liu J, Chen H, Xie Y, Achanzar WE, Zhou YS, Cheng ML, Diwan BA. Estrogen signaling in livers of male mice with hepatocellular carcinoma induced by exposure to arsenic in utero. J.Natl.Cancer Inst. 2004;96:466–474. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waalkes MP, Liu J, Ward JM, Diwan BA. Enhanced urinary bladder and liver carcinogenesis in male CD1 mice exposed to transplacental inorganic arsenic and postnatal diethylstilbestrol or tamoxifen. Toxicol.Appl.Pharmacol. 2006;215:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wanless IR, Wong F, Blendis LM, Greig P, Heathcote EJ, Levy G. Hepatic and portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: possible role in development of parenchymal extinction and portal hypertension. Hepatology. 1995;21:1238–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welch AH, Watkins SA, Helsel DR, Focazio MJ. Arsenic in ground-water resources of the United States. U.S.Geological Survey Fact Sheet. 2000 FS-063-00. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wouters K, van Gorp PJ, Bieghs V, Gijbels MJ, Duimel H, Lutjohann D, Kerksiek A, van Kruchten R, Maeda N, Staels B, van Bilsen M, Shiri-Sverdlov R, Hofker MH. Dietary cholesterol, rather than liver steatosis, leads to hepatic inflammation in hyperlipidemic mouse models of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:474–486. doi: 10.1002/hep.22363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Lane MD, Clemens M, Diehl AM. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin liver injury: implications for the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:2557–2562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]