Abstract

Coarctation of the aorta accounts for about 8% of all congenital heart diseases. Since the first successful case of surgical treatment in 1944 by Crafoord and Nylin1 in Sweden, several surgical techniques have been employed in the treatment of this anomaly. Here, we review by illustration the various surgical options in coarctation of the aorta with emphasis on our preferred technique – the extended resection and end-to-end anastomosis. Why the extended resection technique? Our experience - and that of other institutions - has shown that this is a better option in childhood as it is associated with a lesser degree of recoarctation and subsequent need for re-intervention.2

MeSH: Heart defects, congenital, Child, Thoracic Surgery, Coarctation, aorta

Introduction

Over the years, various surgical techniques have been used in patients with coarctation of the aorta. The choice of procedure has been influenced, on one hand, by the trend at the time of presentation and on the other hand, by the presence of associated cardiac anomalies. In this article, we review the common techniques before dwelling on the one mostly used in recent years.

Patient position and surgical approach

In most cases, the surgical approach is through a left thoracotomy performed usually in the fourth intercostal space. The patient is placed in a lateral position with the left side up (Fig. 1). A curved incision is made, starting at the anterior axillary line and extending posteriorly just below the tip of the scapula where it curves upward to end midway between the vertebral column and scapula over the anteroinferior margin of the trapezius muscle (Fig. 2). This region of the trapezius is divided as well as the latissimus dorsi muscle. The serratus anterior is mostly preserved while the fourth intercostal space is identified and opened. The rib spreader is inserted and opened in stages to avoid rib fractures (Fig. 3). The lung is retracted anteriorly and the mediastinal pleura opened over the aorta downward for about 3 cm below the coarctation site and then upward across the entire left subclavian artery. Stay sutures are placed along each side of the pleural incision. The left superior intercostal vein is ligated and divided. The proximal left subclavian artery, the distal transverse arch and the aortic isthmus are dissected and tapes may be placed around them. To minimize the possibility of damage to the thoracic duct, all dissection is done close to the aorta. When present, “Abbott's artery” which arises from the medial aspect of the isthmus, should be ligated and divided. The ligamentum arteriosum or ductus is also ligated and divided. Care must be exercised to avoid injury to enlarged intercostal arteries.

Figure 1.

Patient position (left lateral approach)

Figure 2.

A curved incision is made on the left thorax

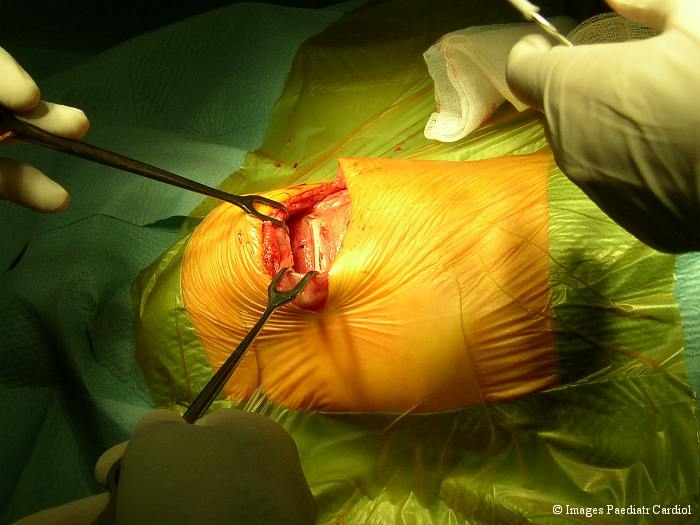

Figure 3.

Left lateral thoracotomy

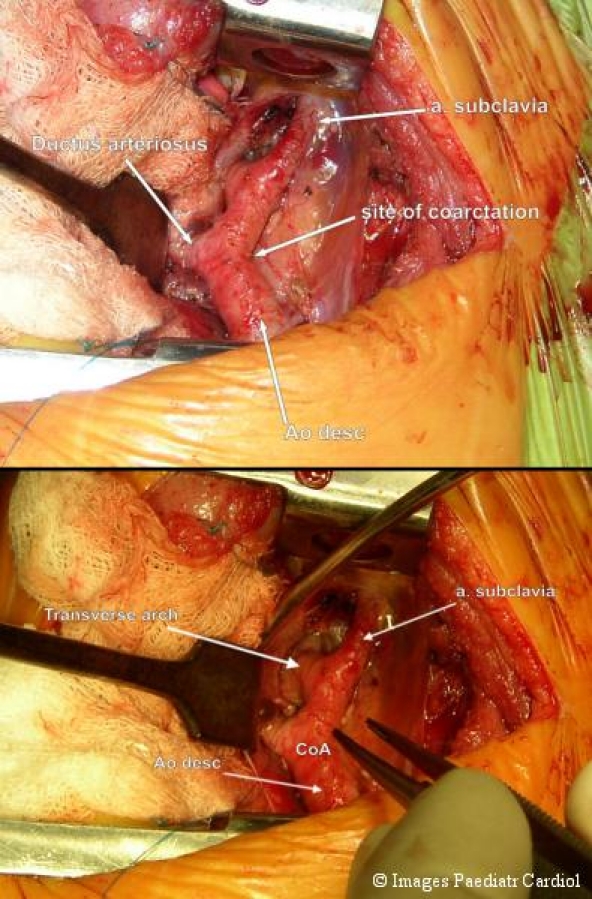

Figure 4.

Mobilization of the aorta and other structures

Figure 5.

A. A view of the site of coarctation after mobilization of key structures. Notice the 6-0 prolene suture around the ductus for ligation. B: In the extended resection technique, the transverse arch is also dissected to enable wider mobility and resection

Surgical techniques

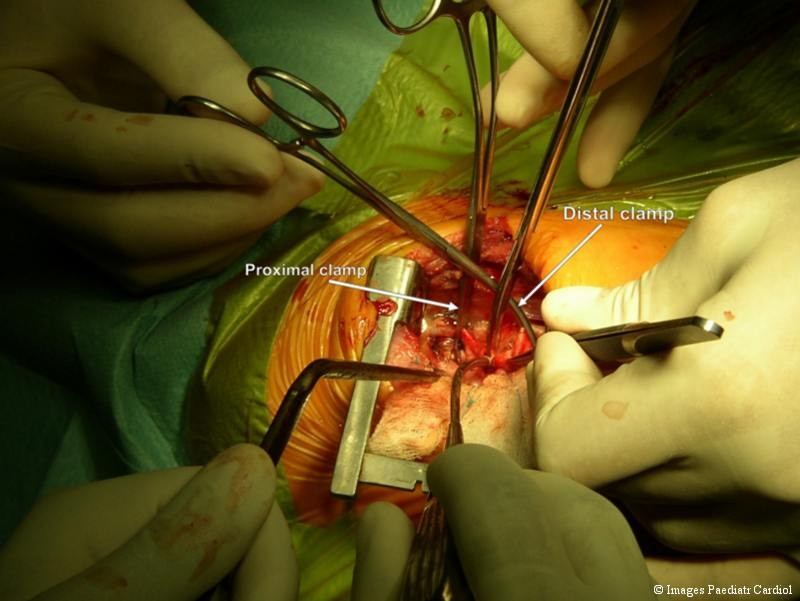

With the patient's nasopharyngeal temperature at about 33°C, aortic clamps are placed above and below the site of coarctation. The position of the vascular clamp, proximal to the site of coarctation, will depend on the site of coarctation and the type of procedure chosen (Fig. 6). It may be necessary to clamp some intercostal arteries using “bull-dog” clips, or tourniquettes.

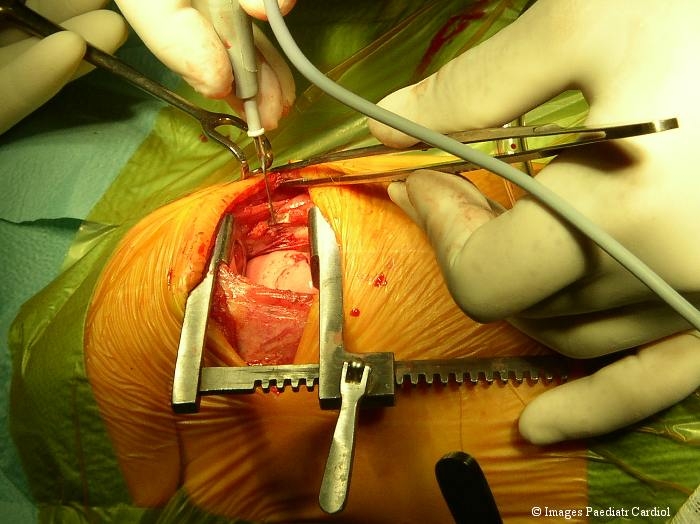

Figure 6.

Position of the aortic clamps and resection of the coarctation site

Resection and end-to-end anastomosis – first developed by Gross et al,3 this technique is still widely used especially in older children and adults. After sufficient mobilisation of the aortic arch and placement of the vascular clamps, the aorta is transected proximal to the coarctation at a level that ensures removal of any narrowed portion of the isthmus as well as the coarctation. A similar transection is made below the site of coarctation. With the aortic clamps held by the second assistant, the end-to-end anastomosis is begun at the deep angle.

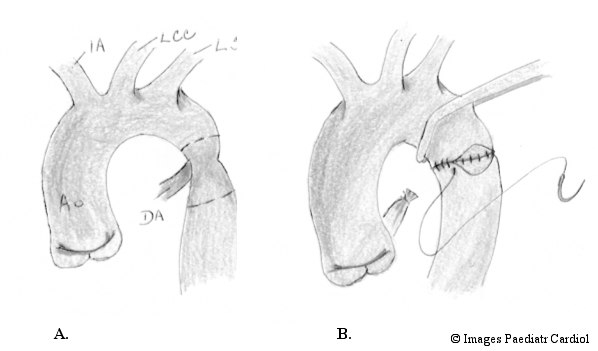

Figure 7.

Resection and end-to-end anastomosis. Dotted lines indicate the points of resection. IA – inominate artery, LCC – left common carotis LS – left subclavian artery DA – ductus arteriosus

Subclavian flap angioplasty – also known as the Waldhausen4 procedure after its author, it involves transection of the subclavian artery and its subsequent use as a flap to enlarge the site of coarctation.

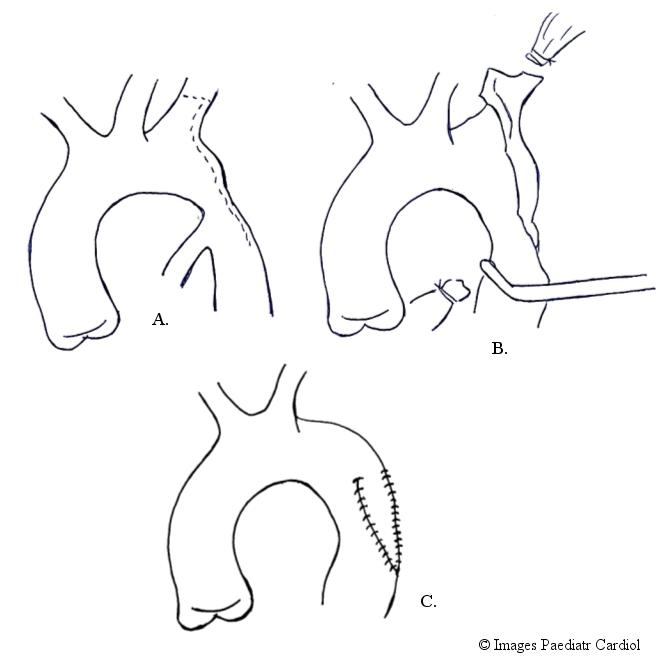

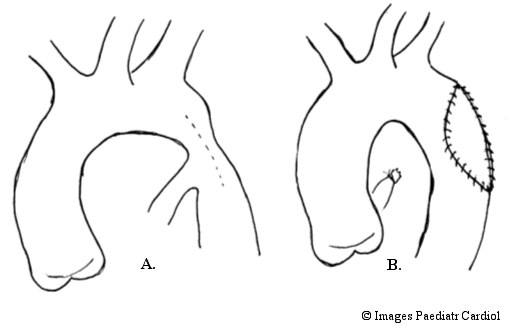

Figure 8.

The subclavian flap technique. The left subclavian artery is transected (B) and used as a flap to enlarge the site of coarctation (C)

Prosthetic patch aortoplasty – this technique was first used by Vosschulte5 in 1957 and entails the use of a prosthetic patch to enlarge the site of coarctation.

Figure 9.

The prosthetic patch aortoplasty. A dacron patch is used to enlarge the site of coarctation. The ducuts is ligated and transected

Extended resection and end-to-end anastomosis. Amato et al6 first published the description of this technique in 1977. Unlike in the first procedure described above, the proximal incision in this case is extended to the under-surface of the aortic arch (Fig. 10) enabling a much larger anastomosis between the proximal and distal parts.

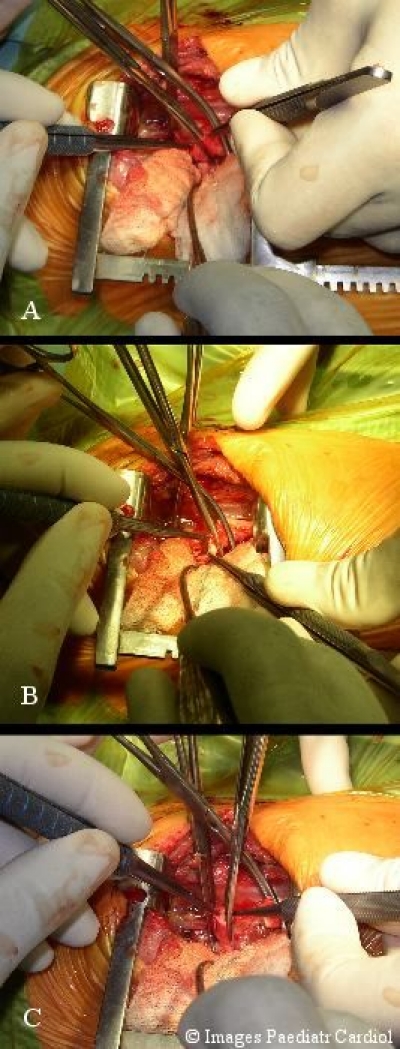

Figure 10.

A. Resection of the coarctation lesion B. Further resection of the distal end may be necessary. C. The proximal incision is extended to the under-surface of the transverse arch (extended resection)

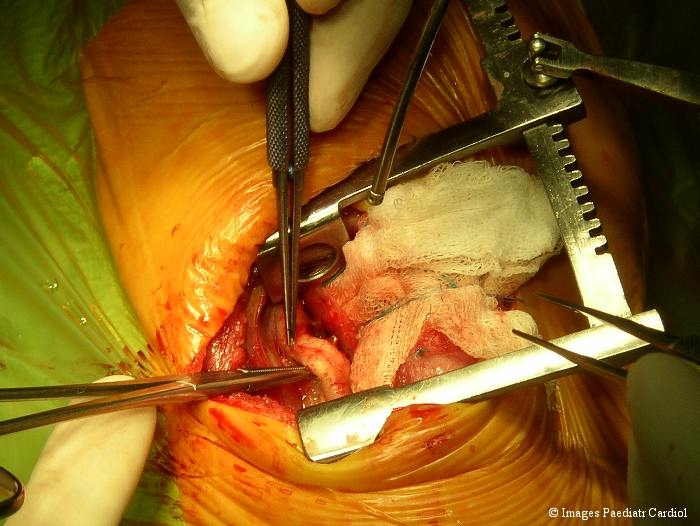

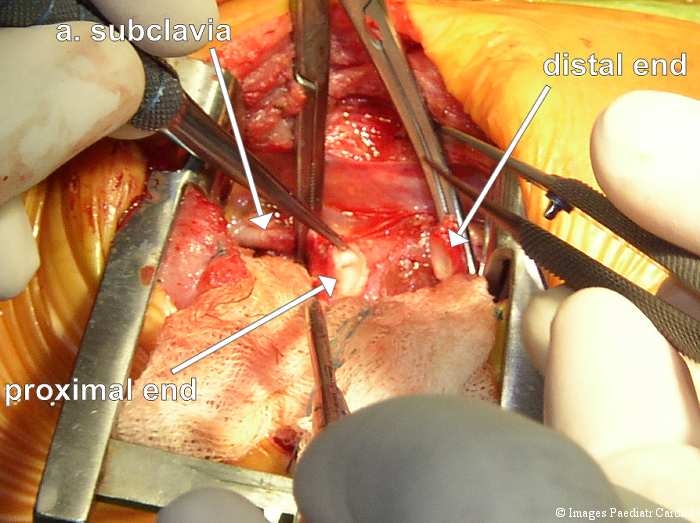

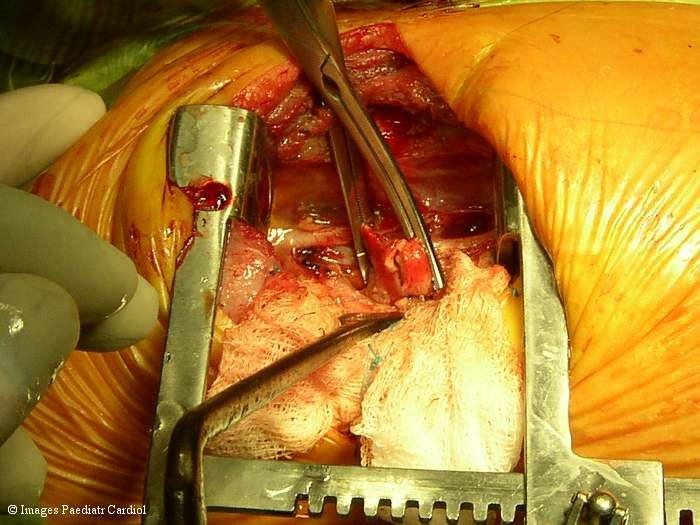

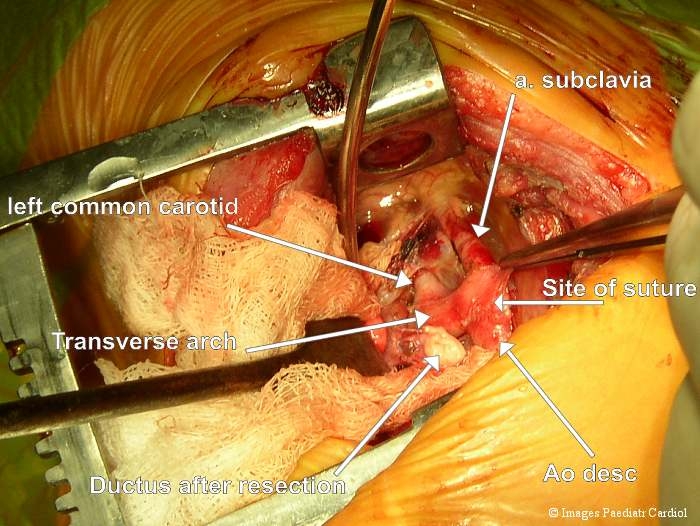

Figure 11.

State after resection

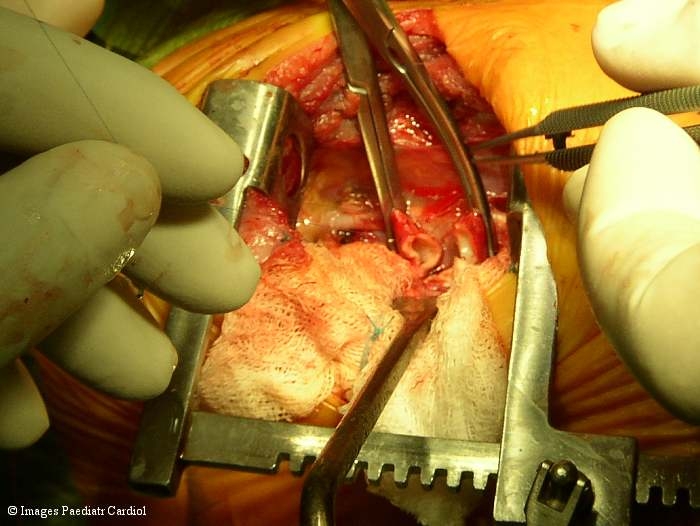

Figure 12.

The aortic clamps are approximated and sutures placed beginning from the deep angle.

Figure 13.

The anastomosis is completed by suturing the superior ends.

Figure 14.

Complete anastomosis. The clamps are released - first, the distal and then the proximal clamp; haemostasis is secured

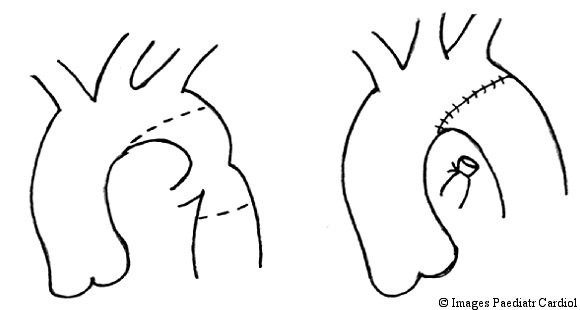

Figure 15.

A line drawing of the extended resection and end-to-end anastomosis technique

Comparison of surgical techniques –our experience

The choice of a particular surgical technique for the treatment of aortic coarctation is determined not only by the type of coarctation lesion but also by factors such as the presence of associated anomalies, the age at presentation and not the least, the surgeon's preference. It is therefore very difficult to identify an “ideal” surgical technique. However, objective comparisons can be made based on such determinants as the rate of recoarctation and freedom from re-intervention. We conducted a study of 201 patients undergoing surgery for coarctation of the aorta over a period of ten years. 139 of these patients had simple or isolated coarctation, 35 had coarctation with ventricular septal defects (VSD), while 27 patients had coarctation with complex intra-cardiac anomalies including hypoplastic left heart syndrome, transposition of the great arteries (TGA) and Shone syndrome. On the whole, 19 cases of recoarctation were recorded, representing 10% of all operated patients. Our results showed that patients who underwent resection and end-to-end anastomosis were at a greater risk of recoarctation than were those who underwent other surgical procedures (P = 0.01). Of the 19 cases of recoarctation, 15 (79%) were patients who underwent resection and end-to-end anastomosis, 2 had extended resection and end-to-end anastomosis while the remaining 2 patients underwent subclavian flap angioplasty and total arch reconstruction respectively. None of the patients who underwent patch aortoplasty had recoarctation. A further look at the cases of recoarctation showed that 12 of the 19 patients were neonates. 10 of these neonates were treated using resection and end-to-end anastomosis, 1 by extended end-to-end anastomosis, while 1 underwent total arch reconstruction. Hence, the use of resection and end-to-end anastomosis in neonates is associated with a higher risk of recoarctation (P>0,0001) than the use of extended resection and end-to-end anastomosis. Details of our findings have been previously published.8,9

Postoperative Complications

In our series, only few complications attributable to surgery were recorded. These include: postoperative bleeding in 4 (2%) patients, phrenic nerve injury in 3 (1.5%), Horner's syndrome in 1(0,5%) and chylothorax in 4 (2%). We did not record any case of paraplegia or CNS damage due to aortic cross-clamping. Protective measures such as cooling the body temperature to about 33° C and maintaining a distal blood pressure of over 45mmHg during cross-clamping were employed in all patients. The duration of aortic cross clamp in most of our cases was less than 20 minutes.

References

- 1.Crafoord C, Nylin G. Congenital coarctation of the aorta and its surgical treatment. J Thorac Surg. 1945;14:347. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backer CL, Mavroudis C, Zias EA, Amin Z, Weigel TJ. Repair of Coarctation with Resection and extended End-to-End Anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1365–1371. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross RE. Surgical correction of coarctation of the aorta. Surgery. 1945;18:673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldhausen JA, Nahrwold DL. Repair of coarctation of the aorta with a subclavian flap. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1966;51:532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vosschulte K. Surgical correction of the aorta by an “isthmus plastic” operation. Thorax. 1961;16:338. doi: 10.1136/thx.16.4.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amato JJ, Galdieri RJ, Cotroneo JV. Role of extended aortoplasty related to the definition of coarctation of the aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;52:615–20. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)90960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirklin JW, Barrat-Boyes BG. Coarctation of the aorta and aortic arch interruption. In: Kirklin JW, Barrat-Boyes BG, editors. Cardiac Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 1263–1325. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omeje IC, Valentikova M, Kostolny M, Sagat M, Nosal M, Siman J, Hraska V. Improved patient survival following surgery for coarctation of the aorta. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2003;104:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omeje IC, Kaldararova M, Sagat M, Sojak V, Nosal M, Siman J, Hraska V. Recoarctation and patients’ freedom from re-intervention – a study of patients undergoing surgery for coarctation of the aorta at the Department of Cardiac Surgery of the Children's University Hospital, Bratislava. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2003;104:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]