Abstract

Protein lysine acetylation has emerged as a key posttranslational modification in cellular regulation, in particular through the modification of histones and nuclear transcription regulators. We show that lysine acetylation is a prevalent modification in enzymes that catalyze intermediate metabolism. Virtually every enzyme in glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, the urea cycle, fatty acid metabolism, and glycogen metabolism was found to be acetylated in human liver tissue. The concentration of metabolic fuels, such as glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids, influenced the acetylation status of metabolic enzymes. Acetylation activated enoyl–coenzyme A hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl–coenzyme A dehydrogenase in fatty acid oxidation and malate dehydrogenase in the TCA cycle, inhibited argininosuccinate lyase in the urea cycle, and destabilized phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in gluconeogenesis. Our study reveals that acetylation plays a major role in metabolic regulation.

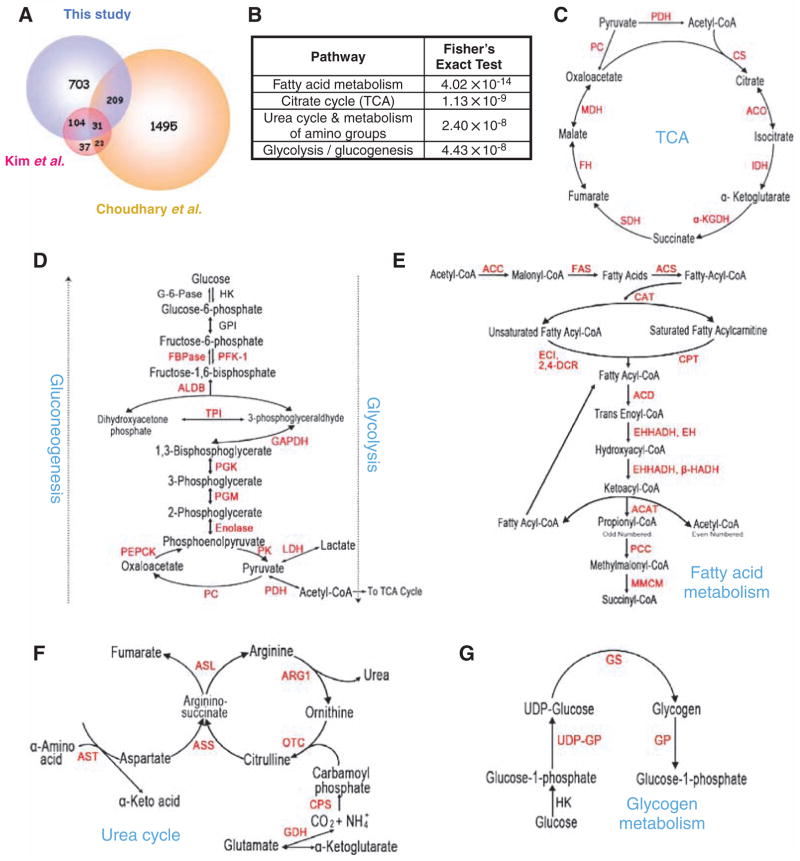

Protein acetylation has a key role in the regulation of transcription in the nucleus (1), but much less is known about non-nuclear protein acetylation and its role in cellular regulation. To investigate non-nuclear protein acetylation, we separated human liver tissues into nuclear, mitochondrial, and cytosolic fractions. Proteins in cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were digested with trypsin and acetylated peptides were purified with an antibody to acetyllysine (fig. S1). The purified peptides were analyzed by tandem liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS). From three independent experiments, we identified more than 1300 acetylated peptides, which matched to 1047 distinct human proteins (table S1), including 703 proteins not previously reported to be acetylated. A previous report identified 195 acetylated proteins from mouse liver (2), and 135 (70%) of these were also present in our data set (Fig. 1A), indicating that our proteomic analysis reached a high degree of coverage. Choudhary et al. very recently reported the identification of 1750 acetylated proteins from a human leukemia cell line (3), but only 240 of these were present in our data set (Fig. 1A). Comparison of these three acetylome data sets indicates that the spectrum of acetylated proteins is highly conserved in the liver between mouse and human, but is very different between liver and leukemia cells.

Fig. 1.

Acetylation of liver metabolic enzymes. (A) Comparison of three acetylation proteomic studies: this study and (2, 3). (B) Preferential acetylation of enzymes in intermediary metabolism. Fisher’s exact test of comparing acetylated proteins to total liver proteins shows that acetylation is much more prevalent in intermediary metabolic enzymes. (C to G) Acetylated metabolic enzymes identified by proteomic survey are marked in red. See supporting online material for key to abbreviations.

We compared the acetylated proteins with the total liver proteome and discovered that enzymes that participate in intermediate metabolism were preferentially acetylated (Fig. 1B). Indeed, almost every enzyme in glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, the TCA cycle, the urea cycle, fatty acid metabolism, and glycogen metabolism was acetylated (Fig. 1, C to G). The high occurrence of metabolic enzymes identified in our MS analysis is apparently not due to the abundance of these proteins, because only a few ribosomal proteins (7 of approximately 80 cytosolic ribosomal proteins) were acetylated (table S1). These results indicate a previously unrecognized and potentially extensive role of acetylation in regulation of cellular metabolism. Therefore, we investigated the effect of acetylation on representative enzymes from four metabolic pathways.

Enoyl–coenzyme A hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl–coenzyme A (EHHADH; EC code 1.1.1.35) catalyzes two steps in fatty acid oxidation (Fig. 1E) (4, 5), and its deficiency causes abnormal fatty acid metabolism (6). We identified four acetylated lysine residues (Lys165, Lys171, Lys346, and Lys584) in EHHADH (table S2). Immunoprecipitation of ectopically expressed FLAG-tagged EHHADH and Western blotting with antibody to acetyllysine confirmed that EHHADH was indeed acetylated. Its acetylation was enhanced by 80% after treatment of cells with trichostatin A [TSA, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDAC) I and II] and nicotinamide (NAM, an inhibitor of the SIRT family deacetylases) (Fig. 2A and fig. S2A). To quantify the acetylation of EHHADH, we used isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) MS of immunoprecipitated EHHADH. TSA and NAM treatment increased Lys171 acetylation from 43.5% to 62% and Lys346 acetylation from 46.8% to 77.8% (Fig. 2B), respectively. Consistently, the corresponding unacetylated peptides were decreased by TSA and NAM treatment. These results show that a substantial portion of EHHADH is acetylated and that EHHADH acetylation can be dynamically regulated in vivo.

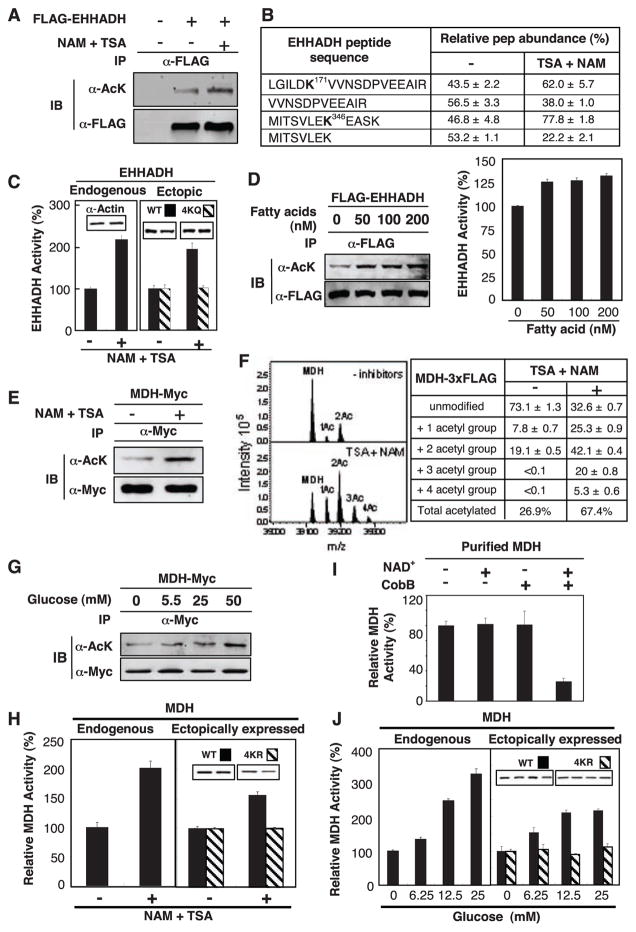

Fig. 2.

Activation of EHHADH and MDH by acetylation. (A) Acetylation of EHHADH was increased by deacetylase inhibitors. Ectopically expressed and immunoprecipitated (IP) EHHADH was examined by immunoblotting (IB) with antibody to acetyllysine (α-AcK). (B) Quantification of EHHADH acetylation by iTRAQ MS. Quantification of peptides was calculated on the basis of relative intensity of the iTRAQ tags. (C) Activation of EHHADH in cells expose to deacetylase inhibitors. Data in this panel and subsequent figures are from triplicate experiments. (D) Fatty acid induced EHHADH acetylation and activity. Acetylation and activity of EHHDH ectopically expressed in HEK293T cells were monitored. (E) MDH acetylation. MDH-Myc was expressed in HEK293T cells and acetylation was determined by immunoblotting. (F) Quantitative MS analysis of MDH. FLAG tagged MDH was overexpressed in HEK293T cells and purified by immunoprecipitation. Eluted intact MDH proteins were analyzed by FTICR MS. (G) Glucose enhances MDH acetylation. (H) Activation of MDH by acetylation. The activity of endogenous and ectopically expressed MDH from Chang and HEK293T cells, respectively, were assayed and normalized against actin. (I) Inactivation of MDH by in vitro deacetylation. Immunoprecipitated MDH was incubated with or without CobB deacetylase and activity was assayed. NAD, an essential cofactor for CobB, was omitted as a negative control. (J) Activation of MDH by glucose. Experiments were similar to (H) except cells were treated with glucose.

To determine the effect of acetylation on enzymatic activity, we treated cultured Chang human liver cells with TSA and NAM and detected a doubling of endogenous EHHADH activity (Fig. 2C). Similar observations were also made with ectopically expressed EHHADH in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2C, right panel). Acetylation of an EHHADH4KQ mutant, which had the four putative acetylation lysine residues replaced by glutamine, was decreased (fig. S2C) and its activity was no longer regulated by TSA and NAM (Fig. 2C). Addition of fatty acids to the culture medium increased acetylation and activity of EHHADH by factors of 1.7 and 1.3, respectively (Fig. 2D and fig. S2D). Thus, acetylation of EHHADH can be regulated by extracellular fuels; this finding supports a physiological role of acetylation in the regulation of EHHADH and fatty acid metabolism.

All seven enzymes in the TCA cycle were acetylated (Fig. 1C and table S1), including malate dehydrogenase (MDH; EC code 1.1.1.37), in which four acetylated lysines were identified (Lys185, Lys301, Lys307, and Lys314; tables S2 and S3). Ectopically expressed MDH was acetylated and its acetylation was increased by a factor of 2.4 in cells treated with TSA and NAM (Fig. 2E and fig. S2E). To quantify MDH acetylation, we performed Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) MS. This approach identified the unmodified full-length MDH and two additional peaks, each with a mass increment of 42.01 daltons, corresponding to mono- and diacetylation (Fig. 2F). When cells were treated with TSA and NAM, MDH acetylation was increased from 26.9% to 67.4% with the appearance of tri- and tetraacetylated forms. Subsequent MS/MS analysis confirmed three of four previously identified acetylation sites (fig. S2F and table S1). These data indicate that acetylation is the predominant form of modification and that a substantial fraction of MDH can be acetylated in the cell.

Exposure of cells to high concentrations of glucose enhanced MDH acetylation by 60% (Fig. 2G and fig. S2G). Inhibition of deacetylase doubled endogenous MDH activity in Chang liver cells (Fig. 2H). Consistently, treatment with TSA and NAM activated the wild-type MDH but not the MDH4KR mutant, in which the four acetylation lysine residues were replaced with arginine, in transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, in vitro deacetylation of immunopurified MDH by CobB deacetylase decreased MDH1 activity (Fig. 2I), indicating that acetylation directly activates MDH. Moreover, high glucose concentrations stimulated enzyme activity of both endogenous and ectopically expressed MDH but had little effect on the MDH4KR mutant (Fig. 2J). These observations indicate that glucose-induced activation of MDH is mediated at least in part through acetylation.

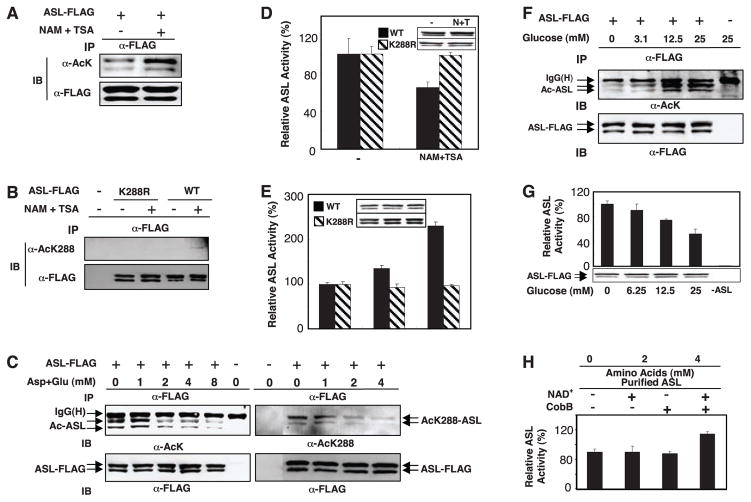

The urea cycle is indispensable for detoxification of ammonium, a product of amino acid catabolism. Mutations in argininosuccinate lyase (ASL; EC code 4.3.2.1) cause argininosuccinic aciduria, the second most common neonatal disorder due to urea cycle malfunction in humans (7). We identified two acetylated peptides in ASL—Lys69 and Lys288 (Fig. 1F and table S2)—and confirmed the acetylation of ectopically expressed ASL (Fig. 3A and fig. S3A). Western blotting with an antibody to acetylated Lys288 showed a factor of 2.8 increase of ASL Lys288 acetylation in cells treated with TSA and NAM (Fig. 3B and fig. S3B). Addition of extra amino acids decreased both total and Lys288 acetylation (Fig. 3C and fig. S3C). An enzymatic assay showed that ASL activity decreased in cells treated with TSA and NAM treatment but increased in cells exposed to amino acids, supporting an inhibitory effect of acetylation on ASL activity (Fig. 3, D and E). The activity of the Lys288 → Arg mutant ASLK288R was refractory to inhibition by TSA and NAM (Fig. 3D) or activation by amino acids (Fig. 3E). The ASLK288R mutation did not alter global protein structure, as determined by limited proteolysis and circular dichroism analyses (fig. S3, D and E). Therefore, extra amino acids appear to activate ASL by decreasing acetylation of Lys288.

Fig. 3.

Inactivation of ASL by acetylation. (A and B) ASL acetylation. FLAG-tagged ASL or ASLK288R was overex-pressed in HEK293T cells, immunoprecipitated, and probed with antibody to acetyllysine (A) or to acetyl-Lys288 (B). (C) Inhibition of ASL acetylation by extra amino acids. ASL was immunoprecipitated from transfected HEK293T cells, which were treated with various amino acid concentrations. (D) Inhibition of ASL in response to NAM and TSA. Wild-type and mutant ASL-K288R (132% of wild-type activity) proteins were expressed in HEK293T cells that were treated with NAM and TSA as indicated. Activity of immuno-precipitated ASL was normalized to total protein. (E) Requirement of Lys288 acetylation for ASL activation by amino acids. Wild-type and mutant ASL proteins were overexpressed in HEK293T cells incubated in medium containing various amino acid concentrations. (F and G) Effects of glucose on acetylation and activity of ASL. ASL was overexpressed in HEK293T cells that were treated with various concentrations of glucose. Acetylation and activity of immunoprecipitated ASL were determined. (H) Activation of ASL by in vitro deacetylation. In vitro deacetylation was similar to Fig. 2I.

The urea cycle is coupled with the TCA cycle because fumarate generated from the urea cycle can be fed into the TCA cycle for energy production or gluconeogenesis (8). We therefore determined the effect of glucose on ASL activity and acetylation. Glucose increased acetylation of ASL by a factor of 2.7 (Fig. 3F and fig. S3F) and decreased activity of ASL by 50% (Fig. 3G). In vitro incubation of ASL immunopurified from mammalian cells with CobB deacetylase increased ASL activity (Fig. 3H), supporting a direct role of acetylation in ASL inactivation. The dual regulation of ASL by both amino acids and glucose indicates that acetylation may have an important role in the coordination of metabolic pathways. In the presence of sufficient glucose, amino acid catabolism for energy production and gluconeogenesis would be inhibited. In the presence of abundant amino acids and low glucose, cells would switch to using amino acids for energy production with enhanced urea cycle activity. Cells may use acetylation to coordinate multiple pathways in order to achieve these metabolic adaptations

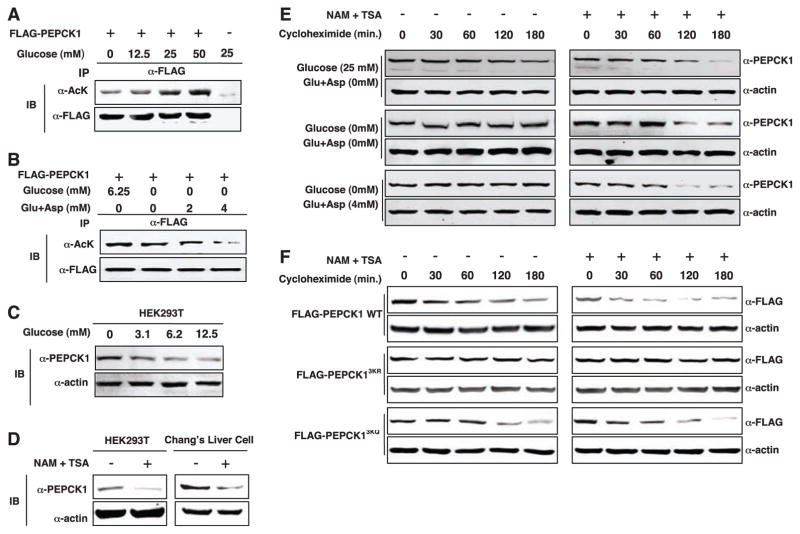

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase1(PEPCK1; EC code 4.1.1.32) is a key regulatory enzyme in gluconeogenesis (Fig. 1D) (9, 10). Three acetylated lysine residues were identified in PEPCK1 by MS analysis (Lys70, Lys71, and Lys594; table S2). Acetylation of PEPCK1 was enhanced in cells treated with high concentrations of glucose (Fig. 4A) but was decreased by addition of amino acids in glucose-free medium (Fig. 4B). These results suggest a potential mechanism by which cells could regulate gluconeogenesis through regulating acetylation of PEPCK1 in response to the availability of extracellular fuels.

Fig. 4.

Destabilization of PEPCK1 by acetylation. (A) Glucose induces PEPCK1 acetylation. (B) Amino acids decrease PEPCK1 acetylation. (C) Glucose induces depletion in of PEPCK1 protein. Endogenous PEPCK levels were detected with a PEPCK1 antibody. (D) TSA and NAM reduce PEPCK1 protein abundance. (E) Glucose destabilizes PEPCK1. Cycloheximide was added at time zero to block translation in HEK293 cells. PEPCK1 protein abundance was determined by Western blotting. (F) Inhibition of deacetylases destabilizes the wild type but not the acetylation-defective mutant PEPCK1.

In searching for an effect of acetylation on the regulation of PEPCK1, we noticed that levels of endogenous PEPCK1 protein were decreased by high glucose (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, treatment with TSA and NAM caused a 70% reduction in the amount of PEPCK1 protein in both HEK293T and Chang liver cells (Fig. 4D). PEPCK1 was stable in cells in glucose-free medium but unstable in high-glucose medium (Fig. 4E). When cells were treated with TSA and NAM, PEPCK1 was unstable even in glucose-free medium or in the presence of amino acids. These results indicate that acetylation may regulate the stability of PEPCK1. We replaced the three putative acetylation lysine residues by arginine (PEPCK13KR) or glutamine (PEPCK13KQ) to abolish or mimic acetylation, respectively. The PEPCK13KR mutant was more stable than the wild type, whereas the PEPCK13KQ mutant remained unstable (Fig. 4F). Moreover, treatment of cells with TSA and NAM failed to destabilize the PEPCK13KR mutant.

The importance of lysine acetylation in the regulation of chromatin dynamics and gene expression is well appreciated. Our study and others extend the scope of cell regulation by lysine acetylation to an extent comparable to that of other major posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination. We show that most intermediate metabolic enzymes are acetylated and that acetylation can directly affect the enzyme activity or stability. We found that acetylation of metabolic enzymes changed in response to the alterations of extracellular nutrient availability, providing evidence for a physiological role of dynamic acetylation in metabolic regulation. The mechanism of acetylation in regulating metabolism may be conserved during evolution. Many metabolic enzymes in Escherichia coli are acetylated, although the functional importance of these acetylations has not been investigated (11). We propose that lysine acetylation is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism involved in regulation of metabolism in response to nutrient availability and cellular metabolic status. Acetylation may play a key role in the coordination of different metabolic pathways in response to extracellular conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Fudan MCB laboratory for their valuable inputs throughout this study and S. Jackson for reading the manuscript. Supported by the 985 program from the Chinese Ministry of Education, state key development programs of basic research of China (grants 2009CB918401 and 2006CB806700), the national high technology research and development program of China (grant 2006AA02A308), Chinese National Science Foundation grants 30600112 and 30871255, Shanghai key basic research projects (grants 06JC14086, 07PJ14011, 08JC1400900), and NIH grants R01GM51586, R01CA108941, and R01CA65572 (K.L.G., X.C., and Y.X.).

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Yang XJ, Seto E. Mol Cell. 2008;31:449. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SC, et al. Mol Cell. 2006;23:607. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudhary C, et al. Science. 2009;325:834. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvares K, et al. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh CS, et al. Cancer Lett. 2006;233:297. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watkins PA, et al. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:771. doi: 10.1172/JCI113956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevisson E, et al. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:694. doi: 10.1002/humu.20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jungas RL, Halperin ML, Brosnan JT. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:419. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lardy H, Hughes PE. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1984;24:171. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152824-9.50023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.She P, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6508. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6508-6517.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, et al. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:215. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800187-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.