Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen capable of group behaviors, including biofilm formation and swarming motility. These group behaviors are regulated by both the intracellular signaling molecule c-di-GMP and acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing systems. Here, we show that the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) system also contributes to the regulation of swarming motility. Specifically, our data indicate that 2-heptyl-4-quinolone (HHQ), a precursor of PQS, likely induces the production of the phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA), which in turn acts via an as-yet-unknown downstream mechanism to repress swarming motility. We show that this HHQ- and PCA-dependent swarming repression is apparently independent of changes in global levels of c-di-GMP, suggesting complex regulation of this group behavior.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic human pathogen capable of coordinated group behaviors, including swarming motility and biofilm formation. These group behaviors are regulated by both the intracellular signaling molecule c-di-GMP and the acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing (QS) systems (7, 19, 26, 32, 53).

P. aeruginosa swarming motility occurs on semisolid surfaces (i.e., on 0.5 to 0.7% agar) and is characterized by a fractal-like pattern of tendrils emanating from the point of inoculation (5, 24). Swarming motility requires a functional flagellum and the production of rhamnolipid biosurfactants, which are regulated by the acylhomoserine lactones 3-oxo-C12-HSL and 3-OH-C4-HSL (5, 35). Type IV pili, while not required for swarming, can impact swarm patterning (5).

Swarming motility and biofilm formation are inversely correlated in P. aeruginosa PA14, and this relationship is, in part, dependent on the intracellular level of c-di-GMP (26, 32, 33). We previously reported that a variety of amino acids could impact these group behaviors. In particular, we showed that arginine represses swarming and stimulates biofilm formation via an elevated intracellular pool of c-di-GMP (1). A ΔsadC ΔroeA double mutant results in reduced intracellular levels of this dinucleotide signal and thus relieves the arginine-mediated repression of swarming (1, 33).

Relevant to the human host, arginine appears to be a significant component of the cystic fibrosis patient (CF) lung (37). Recent data show that various regions of the CF lung are either low in oxygen or anoxic (45, 55). While P. aeruginosa can ferment arginine under such oxygen-limiting conditions (49), arginine in the CF lung is more likely assisting in redox balancing and cellular homeostasis under conditions promoting pyruvate fermentation and anaerobic respiration rather than promoting growth. Given the potential significance of arginine in the context of the CF lung and the arginine-dependent repression of swarming motility, we sought to identify molecular mechanism(s) of swarming regulation by arginine.

Here, we report the role of the signal molecule 2-heptyl-4-quinolone (HHQ) in the repression of swarm motility. We also show that HHQ, an intermediate in the synthesis of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS), controls swarming by positively regulating phenazine production. Of the four phenazines produced by P. aeruginosa, phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA) modulates swarming motility via an unknown downstream mechanism. We present data to show that this HHQ/PCA-dependent pathway for swarm repression is c-di-GMP independent. Lastly, we present a model for the control of swarming motility that may be relevant in the context of the CF lung.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth media.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain UCBPP-PA14 (abbreviated as P. aeruginosa PA14) was used in this study. P. aeruginosa PA14 and Escherichia coli were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) at 37°C and, when appropriate, supplemented with antibiotics at the following concentrations: gentamicin (Gm), 10 μg ml−1 (E. coli) and 50 μg ml−1 (P. aeruginosa); carbenicillin (Cb), 50 μg ml−1 (E. coli) and 250 μg ml−1 (P. aeruginosa). M63 minimal medium supplemented with glucose (0.2%), arginine (0.4%), and MgSO4 (1 mM) was used for c-di-GMP analysis. Swarming medium contained M8 salts (24), with glucose, arginine, and MgSO4 at the same concentrations as those described for M63. When indicated, arabinose was added at 0.2%, and HHQ and PQS dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were added to the swarm agar medium (final concentration [Cf] = 0.5 μM), with equal volumes of DMSO in control plates. Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA), from Princeton Bio-Molecular Research (Princeton, NJ), was added to swarm medium from a stock of 500 mM in 5× M8, as indicated.

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, primer, or plasmid | Relevant genotype or primer sequence (5′→3′) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. cerevisiae InvSc1 | MATa/MATα leu2/leu2 trp1-289/trp1-289 ura3-52/ura3-52 his3-Δ1/his3-Δ1 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80 lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Str) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| E. coli S17-1 (λpir) | thi pro hsdR-hsdM+ ΔrecA RP4-2::TcMu-Km::Tn7 | 48 |

| SMC 232 | Wild-type P. aeruginosa PA14 | 40 |

| SMC 3809 | SMC 232 ΔsadC ΔroeA | 33 |

| SMC 5013 | SMC 232 ΔpqsA | Deb Hogan |

| SMC 5014 | SMC 232 ΔpqsB | This study |

| SMC 5015 | SMC 232 ΔpqsD | This study |

| SMC 5019 | SMC 232 ΔphnAB | Deb Hogan |

| SMC 5018 | SMC 232 ΔpqsR | 10 |

| SMC 5016 | SMC 232 ΔpqsE | This study |

| SMC 5017 | SMC 232 ΔpqsH | 10 |

| SMC 5021 | SMC 232 ΔlasR | 21 |

| SMC 5022 | SMC 232 rhlR::tetR | 20 |

| SMC 5023 | SMC 232 ΔlasR rhlR::tetR | 10 |

| SMC 5020 | SMC 232 ΔphzA1-G1 ΔphzA2-G2 | 13 |

| SMC 5127 | SMC 232 ΔphzH | This study |

| SMC 5128 | SMC 232 ΔphzM | This study |

| SMC 5129 | SMC 232 ΔphzHM | This study |

| SMC 5123 | SMC 232 SXO phzS | This study |

| SMC 5124 | SMC 232 ΔphzH SXO phzS | This study |

| SMC 5125 | SMC 232 ΔphzM SXO phzS | This study |

| SMC 5126 | SMC 232 ΔphzHM SXO phzS | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMQ30 | Suicide vector; GmrsacB URA3 CEN6/ARSH4 lacZα | 47 |

| pKO pqsB | PA0997 (pqsB) knockout construct in pMQ30 | This study |

| pKO pqsD | PA0999 (pqsD) knockout construct in pMQ30 | This study |

| pKO pqsE | PA1000 (pqsE) knockout construct in pMQ30 | This study |

| pDPM73 | Cloning vector (derivative of pMQ70), Ampr CbrURA3 PBAD-araC CEN6/ARSH4 | 47 |

| pPqsA | PA0996 (pqsA); under the control of PBAD promoter; Cbr | This study |

| Primers | ||

| pqsB dwst For | CTG TTT TAT CAG ACC GCT TCT GCG TTC TGA TGG ATT CTG TCG GGC GTT CGC TAC G | |

| pqsB dwst Rev | AGT TCA CAG GTG ATC GCT GCC AGT TTG ACC GCC CGT TCC TCC GGA AGG TTG TCG TGA | |

| pqsB upst For | TTA TCA CGA CAA CCT TCC GGA GGA ACG GGC GGT CAA ACT GGC AGC GAT CAC CTG TGA AC | |

| pqsB upst Rev | GCG GAT AAC AAT TTC ACA CAG GAA ACA GCT CGG CGA AAC CCC AGC CGG TGG C | |

| pqsD dwst For | TTG ACC GGG AGC CGA AAG CCG TAC AGC CCT CCT CGG ACA CCG TGG TTC | |

| pqsD dwst Rev | CTG TTT TAT CAG ACC GCT TCT GCG TTC TGA TAC CTC AGC GAG TCT TGG TGG CAA TTC TG | |

| pqsD upst For | GCG GAT AAC AAT TTC ACA CAG GAA ACA GCT CGC GAC GCT AGC GCG CAA C | |

| pqsD upst Rev | GTG TCC GAG GAG GGC TGT ACG GCT TTC GGC TCC CGG TCA ACT GGA T | |

| pqsE dwst For | CTG TTT TAT CAG ACC GCT TCT GCG TTC TGA TAA TCC GAT CCT GGC CGG GCT GGG TTT | |

| pqsE dwst Rev | GGC GGC GAT CGC CGC AAT GGA TGT CCC GCC GGC CGG TTC ACC TCC TCA GGT TTA CGG TAC | |

| pqsE upst For | GTA CCG TAA ACC TGA GGA GGT GAA CCG GCC GGC GGG ACA TCC ATT GCG GCG ATC | |

| pqsE upst Rev | GCG GAT AAC AAT TTC ACA CAG GAA ACA GCT GTA CGG GCT GGG GTT GCC CAG GCA C | |

| phzH dwst For | CTG TTT TAT CAG ACC GCT TCT GCG TTC TGA TAC GGA TCG TTG ATC GCT GTT TCG ACC AA | |

| phzH dwst Rev | CGC CAC GCC CCG CGT CAC GCA GGG AAA CTC CTC TAA TTG ATG TTT TAT CGG GAA ACT C | |

| phzH upst For | TCA ATT AGA GGA GTT TCC CTG CGT GAC GCG GGG CGT GGC | |

| phzH upst Rev | GCG GAT AAC AAT TTC ACA CAG GAA ACA GCT CAA GGC CAC TCG CAT GCC GCG | |

| phzM dwst For | CTG TTT TAT CAG ACC GCT TCT GCG TTC TGA TGT CGC ACT CGA CCC AGA AGT GGT TCG G | |

| phzM dwst Rev | CAG CCG TTG AGA GTT CCG GTC TTT TAT TCT CTC TCG TTA CAC ATT TCC GTA ACC CGA | |

| phzM upst For | GTA ACG AGA GAG AAT AAA AGA CCG GAA CTC TCA ACG GCT GGC CCC | |

| phzM upst Rev | GCG GAT AAC AAT TTC ACA CAG GAA ACA GCT CCG CGC CGA AGC GGC CGA C | |

| sxo phzS For | TGT TTT ATC AGA CCG CTT CTG CGT TCT GAT CAG TAC TCG ATC CAT CGC GGC GAA C | |

| sxo phzS Rev | GCG GAT AAC AAT TTC ACA CAG GAA ACA GCT GCG AAG AAC GGC AAC ACG TCT TCC AG | |

| PA14_51430 For | TTT TTT GGG CTA GCC CAA GGA AGC ACA ACC ATG TCC ACA TTG GCC AAC CTG ACC GAG GTT | |

| PA14_51430 Rev | AGA AGA TTT TCA GCC TGA TAC AGA TTA AAT TCA ACA TGC CCG TTC CTC CGG AAG GTT G | |

| pqsB For (confirm) | CCG AGC TGC GCC ACC TGG CC | |

| pqsB Rev (confirm) | CAG CGA ACA CCG GAT CGT CGT TTT CGT A | |

| pqsD For (confirm) | GTG TGC TGA GGC ATC GCC ATG TTG AAC C | |

| pqsD Rev (confirm) | CTG GAC GTC CCC CAA CAG GCA CAG GTC | |

| pqsE For (confirm) | GTT CCG GCG CGA CCT GGG GCG | |

| pqsE Rev (confirm) | TTT CCC CCA ATT GCG ACC GCT GCC | |

| phzH For (confirm) | GCG CCG CGA GCG GAC GG | |

| phzH Rev (confirm) | TCG AGA ACA ACG ACA AGA AGC GCT TCG | |

| phzM For (confirm) | CGA AGG AAT GGA TGT AGT GGT TCT CGC AAT AG | |

| phzM Rev (confirm) | TCG ACG CGC AGT GGG AAA TCG ACC | |

| phzA For (RT) | AAC GGT TAC AGC GGC ACA GCC TGT TC | |

| phzA Rev (RT) | CTC GAC CCA GAA GTG GTT CGG ATC CTC | |

| phzG For (RT) | TTT CCG AGT CCC TCA CCG GGA CCA TC | |

| phzG Rev (RT) | CGC GCT CGC CGA GTT CGG C |

Molecular techniques.

Plasmids constructed during the course of this study were prepared using homologous recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (47). All restriction enzymes were obtained from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). Plasmids constructed in yeast were subsequently extracted by a modified “smash and grab” method (2) and electroporated into E. coli for confirmation by colony PCR (54), with minor modifications. Plasmids were propagated in E. coli Top 10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for complementation and in E. coli S17 for allelic exchange. Complementation constructs were extracted from bacteria using the Qiagen spin miniprep kit (Valencia, CA) and electroporated into P. aeruginosa, as previously reported (9). Allelic exchange constructs were conjugated into P. aeruginosa, as previously reported (25), and exconjugants were selected and counterselected by gentamicin and 5% sucrose, respectively. All resulting mutations were verified by PCR amplification of genomic DNA from mutants using primers flanking the deletion mutation and sequencing of the PCR products. Plasmid-harboring cells were maintained with necessary antibiotic selection on both LB liquid and agar. All transposon mutants were verified for correct transposon insertions via arbitrary primed PCR using nested primers to amplify genomic DNA, modified from published reports (3, 36), followed by sequencing of the PCR products.

RNA extraction and expression studies.

Stationary-phase, LB-grown P. aeruginosa cultures were subcultured 1:1,000 into glucose-arginine M8 medium and then incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted from the glucose-arginine-grown cultures using the High Pure RNA isolation kit, and subsequent cDNA synthesis was performed with the Transcriptor first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (both kits are from Roche Applied Bioscience, Indianapolis, IN). Semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (semi-qRT-PCR) was performed with NEB Taq DNA polymerase (Ipswich, MA).

To verify candidate genes from the microarray reanalysis, strains were scraped from glucose-arginine swarm motility plates following incubation at 37°C, and total RNA was extracted using the High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche Applied Bioscience, Indianapolis, IN). cDNA was synthesized using the DyNAmo cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and subsequent qPCR studies were performed using SYBR green PCR master mix on a 7500 fast real-time PCR system (both are from Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA).

Measurement of c-di-GMP levels.

Nucleotide extraction from P. aeruginosa cultures were performed as previously reported (33, 34), with modifications. Briefly, a stationary-phase, LB-grown P. aeruginosa culture was subcultured 1:100 into glucose-arginine M63 medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.04. Cultures were harvested at an OD600 of 0.4 by centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min at 4,500 × g. Pellets were resuspended in 250 μl of extraction buffer (acetonitrile-methanol-water [40:40:20] plus 0.1 N formic acid) and incubated at −20°C for 30 min. Cell debris was pelleted for 5 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant was adjusted to a pH of ∼7.5 by adding 15% (NH4)2HCO3. Nucleotide extractions were analyzed via the Acquity Ultra Performance liquid chromatography (LC) system coupled to a Quattro Premier XE mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) (34). Each sample was compared to a standard curve of c-di-GMP resuspended in water to quantify the amount of nucleotide.

Microarray.

The microarray data analyzed in this study was retrieved from the NCBI (GEO number GSE17147). To analyze these data, Affymetrix probe fluorescence values were first summarized and normalized using RMA (robust multichip average) (23) as implemented in Bioconductor. We then calculated the standard deviation for each probe and used Pearson distance to hierarchically cluster the 50 probes with the largest standard deviations.

RESULTS

Isolation and initial characterization of the PA14_36280::Tn and pqsA::Tn mutants.

Two distinct group behaviors, swarming motility and biofilm formation, are inversely correlated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14, and these phenotypes are regulated at least in part by the intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP (4). We recently identified two diguanylate cyclases (DGC), SadC and RoeA, and phosphodiesterase (PDE) BifA as responsible for regulating biofilm formation and swarming in P. aeruginosa PA14 (26, 32, 33). We also observed repression of swarming motility in the presence of arginine, and this effect is dependent upon the SadC and RoeA DGCs (Fig. 1A) (1).

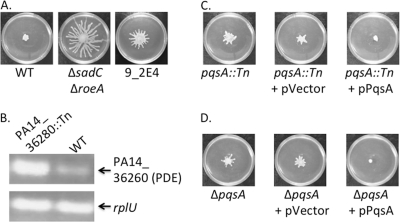

Fig. 1.

Mutating pqsA relieves arginine-mediated repression of swarming motility. (A) Representative swarm phenotypes of the wild type (WT), ΔsadC ΔroeA mutant, and 9_2E4 mutant on swarm medium containing arginine. This and all subsequent swarm motility assays reported here are performed on swarm medium supplemented with 0.4% arginine. (B) Semi-qRT-PCR analysis comparing the expression levels of the PA14_36260 gene, a known phosphodiesterase (PDE) (27), in the PA14_36280::Tn mutant and wild type (WT). The expression of the rplU gene was used as a control for a gene not expected to differ between these strains. (C) Representative swarm phenotypes of the pqsA::Tn mutant, the pqsA::Tn strain carrying the vector control (+pVector), and the strain complemented with a wild-type copy of the pqsA gene (pPqsA). (D) Representative swarm phenotypes of the ΔpqsA mutant, the mutant carrying a vector control (+pVector), and the mutant complemented with a wild-type copy of the pqsA gene (+pPqsA).

To identify additional genes that may play a role in mediating the arginine-dependent repression of swarming motility in P. aeruginosa PA14, we performed a genetic screen to identify mutants that could swarm in the presence of this amino acid. This screen was prompted in part by the fact that deletion of the sadC and roeA DGCs could restore swarming on arginine (Fig. 1A), indicating that we could identify such a class of mutants.

We began by screening the P. aeruginosa PA14 nonredundant mutant library (29) for strains capable of swarming on arginine-containing medium. A total of 5,663 transposon mutants were screened on arginine medium, of which 75 showed a positive swarming phenotype in the initial screen. These 75 positive candidates were retested, and only 3 mutants demonstrated a reproducible swarm-positive phenotype on arginine medium. One of the mutants could not be complemented and was not examined further. The characterization of the other two mutants, with insertions in the PA14_36280 and pqsA genes, is presented here.

Consistent with the phenotypes observed in the ΔsadC ΔroeA mutant, we expected that candidates with transposon insertions in genes affecting c-di-GMP metabolism or signaling would emerge from the screen (i.e., with reduced c-di-GMP levels). The candidate mutant 9_2E4 (Fig. 1A) had a transposon insertion in the PA14_36280 gene, upstream of a gene encoding a documented PDE, PA14_36260, which corresponds to the PA2200 gene of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (27). Because the transposon used to generate this library has an outward-facing promoter, we predicted that the swarm phenotype of this mutant might have been due to the induction of expression of the PDE-encoding PA14_36260 gene. Consistent with this idea, semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed a higher level of expression of the PDE-encoding PA14_36260 gene in the PA14_36280::Tn (9_2E4) mutant than in the wild type (WT) (Fig. 1B). This mutant helped serve to validate the utility of this screening approach.

We also isolated an additional candidate, designated 1_2A5, which demonstrated swarming motility on arginine swarm medium, albeit with a less striking phenotype than observed for the ΔsadC ΔroeA double mutant (compare Fig. 1A to C, left). The transposon insertion in the 1_2A5 mutant was mapped to the pqsA gene. The pqsA gene has no known DGCs or PDEs in close proximity. Introduction of a wild-type copy of the pqsA gene on a plasmid complemented the 1_2A5 mutant, that is, restored the swarming-repressed phenotype (Fig. 1C).

To confirm the finding above, a strain carrying a deletion of the pqsA gene was also tested on the arginine swarm medium; the ΔpqsA deletion strain, like the transposon insertion mutant, was capable of swarming on arginine-containing medium (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, introduction of the wild-type pqsA gene into the ΔpqsA mutant strain, but not the vector control, complemented the swarming phenotype on arginine medium (Fig. 1D).

Role of pqs genes in arginine-mediated swarm repression.

The pqsA gene is the first gene in an operon that also includes the pqsBCDE genes. This operon and the bicistronic phnAB operon are similarly regulated (Fig. 2A) (8, 31). The pqsABCD and phnAB genes are required for the synthesis of HHQ, the immediate precursor of 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4-quinolone (PQS) (Fig. 2A) (for a review, see reference 22). HHQ is converted into PQS by the flavin-dependent monooxygenase encoded by the pqsH gene, which lies distant from the PQS operon (12, 18, 46). Although the pqsE gene is also in the pqsABCDE operon, it has no known biosynthetic function but rather is shown to be required for the expression of genes under the control of PQS (17, 42). Lastly, the LysR-type transcriptional regulator PqsR (also known as MvfR) positively regulates the expression of the PQS operons (pqsABCDE and phnAB genes) and HHQ production (50, 57).

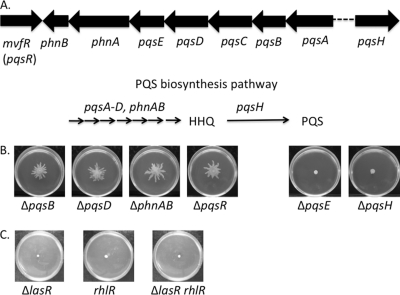

Fig. 2.

HHQ mediates swarm repression by arginine. (A, top) Organization of the PQS operon (pqsABCDE, phnAB, pqsR [mvfR]) and the distant pqsH gene in P. aeruginosa PA14; (bottom) a simplified biosynthetic pathway of PQS. The genes involved in each portion of the pathway are indicated above the arrows. Also shown are the precursor, HHQ, and the final product, PQS. (B) Representative swarm phenotypes of the ΔpqsB, ΔpqsD, ΔphnAB, ΔpqsR, ΔpqsE, and ΔpqsH mutants. (C) Representative swarm phenotypes of other quorum-sensing (QS), ΔlasR, rhlR::tetR, and ΔlasR rhlR::tetR mutants.

Following the isolation of a mutation in the pqsA gene from the screen, we hypothesized that arginine's repressive effect on swarming motility was mediated via the PQS system and its quinolone molecule product(s). To test this hypothesis, we assayed strains that carry various mutations in the pqsABCDE and phnAB genes as well as the pqsH gene for their ability to swarm on the arginine medium. The ΔpqsB, ΔpqsD, ΔphnAB, and ΔpqsR mutants, similar to the ΔpqsA mutant, demonstrated swarming motility in the presence of arginine (Fig. 2B, left). However, under these same conditions, two mutants—the ΔpqsE and ΔpqsH mutants—failed to swarm (Fig. 2B, right).

Because the PQS system is one of three identified quorum-sensing (QS) systems in P. aeruginosa, we also tested strains with mutations in two other QS systems, Las and Rhl (16), for their potential role in swarm repression in the presence of arginine. Strains carrying mutations in the Las and Rhl systems, the ΔlasR, rhlR::tetR, and ΔlasR rhlR::tetR mutants, like the wild type, did not swarm on arginine-containing medium (Fig. 2C). Similarly, when inoculated on glucose medium that typically favors swarming motility by P. aeruginosa, none of these mutants were able to swarm (data not shown), indicating a general defect in swarming for these mutant strains, likely due to impaired rhamnolipid surfactant production (24, 44). Together, these data suggest that swarm repression mediated by arginine is dependent on the synthesis of HHQ but not PQS or the products of the Las or Rhl QS systems.

HHQ cross-complementation restores swarm repression by arginine.

Our genetic data indicated a role for HHQ in repressing swarming motility on arginine. Previous work demonstrated that PQS can be transferred via outer membrane vesicles (OMV) (30) or secreted (6) by P. aeruginosa. HHQ has also been shown to be secreted (12). We exploited these facts to test the hypothesis that HHQ mediates swarm repression on arginine medium by performing cross-complementation assays. In these experiments, the two test strains were mixed in a 1:1 ratio prior to inoculation on the arginine-containing swarm plate.

In mixtures where HHQ is produced by at least one of the two strains (e.g., WT versus the ΔpqsA mutant, the ΔpqsA mutant versus the ΔpqsH mutant), swarming motility was repressed, but not when both lacked the ability to synthesize HHQ (e.g., the ΔpqsA mutant versus the ΔpqsB mutant, the ΔpqsB mutant versus the ΔpqsD mutant) (Table 2). As a control, we also “self-crossed” mutants and showed that strains lacking HHQ production (e.g., the ΔpqsA mutant versus the ΔpqsA mutant, the ΔpqsR mutant versus the ΔpqsR mutant) swarmed, while strains capable of HHQ production (e.g., WT versus WT, the ΔpqsH mutant versus the ΔpqsH mutant) did not swarm on arginine medium (Table 2). These results imply that HHQ can be transferred between cells to repress swarming motility, and furthermore, these findings are consistent with the model that HHQ rather than PQS represses swarming motility.

Table 2.

Swarm repression is mediated by a transferrable signal

| Strain | Swarming phenotypea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ΔpqsA mutant | ΔpqsB mutant | ΔpqsD mutant | ΔpqsE mutant | ΔpqsH mutant | ΔpqsR mutant | ΔphnAB mutant | |

| WT | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ΔlasR mutant | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| rhlR::tetR mutant | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ΔlasR rhlR::tetR mutant | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ΔpqsA mutant | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| ΔpqsB mutant | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| ΔpqsD mutant | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| ΔpqsE mutant | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| ΔpqsH mutant | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| ΔpqsR mutant | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ΔphnAB mutant | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

−, negative swarming phenotype; +, positive swarming phenotype. Phenotypes were scored based on observed tendril formation on at least six replicate plates.

Exogenous HHQ, but not PQS, represses swarming motility on arginine.

The combination of our genetic and cross-complementation data above suggested a role for HHQ, but not PQS, in mediating swarm repression on arginine medium. To explore this hypothesis further, we added exogenous, chemically synthesized and purified HHQ or PQS (both at 0.5 μM) to assess their effects on swarming motility. As a control, we added equal volumes of DMSO, which was used to solubilize these compounds. While HHQ was effective in repressing swarming motility by the Δpqs mutants, neither PQS nor DMSO repressed swarming by these same mutants (Table 3). In contrast, the ΔpqsR mutant demonstrated swarming motility regardless of HHQ or PQS supplementation to the arginine medium (Table 3).

Table 3.

Swarming is repressed by the addition of exogenous HHQ

| Strain | Swarming phenotypea |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | HHQ | PQS | |

| WT | − | − | − |

| ΔsadC ΔroeA mutant | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| ΔpqsA mutant | + | − | + |

| ΔpqsB mutant | + | − | + |

| ΔpqsD mutant | + | − | + |

| ΔphnAB mutant | + | − | + |

| ΔpqsR mutant | + | + | + |

−, negative swarming phenotype (e.g., no swarming); +, positive swarming phenotype; ++, hyperswarming phenotype. Phenotypes were scored based on observed tendril formation on at least five replicate plates.

We also wanted to explore whether c-di-GMP- and HHQ-mediated repression of swarming motility comprise a single regulatory pathway. To begin to address this question, we performed swarming motility assays by mixing the WT and the ΔsadC ΔroeA double mutant; this mixture of strains was still capable of swarming (data not shown). Furthermore, contrary to the Δpqs mutants' responses described above, the ΔsadC ΔroeA double mutant produced a robust swarm even when exogenous HHQ or PQS was added to the medium (Table 3).

Taken together, these results suggest that both HHQ and the PqsR protein contribute to the repression of swarming motility on arginine medium. Furthermore, our data suggest that HHQ- and c-di-GMP-mediated repression of swarming motility may be via distinct pathways, a point addressed in more detail below.

Phenazines are downstream effectors in HHQ-mediated, arginine-dependent swarm repression.

The data presented here support a model wherein HHQ, jointly with the PqsR protein, represses swarming motility when arginine is present. We next sought to identify a candidate gene(s) regulated by HHQ that might contribute to arginine-mediated swarm repression. In particular, our emphasis was to distinguish HHQ-regulated genes from PQS-regulated genes, as HHQ but not PQS contributes to swarm repression under our experimental conditions. To identify HHQ-regulated gene(s), we reanalyzed a published set of microarray studies (11, 28) and compared the expression profiles of three strains—the wild type and the ΔpqsR and ΔpqsE mutants—to identify gene(s) whose expression is HHQ dependent.

Our rationale for choosing the three strains is as follows: the wild-type strain produces both PQS and HHQ molecules and is capable of responding to these signals. The ΔpqsR mutant, on the other hand, lacks the positive regulator of the PQS operons, which negatively impacts HHQ and PQS biosynthesis and which renders the ΔpqsR mutant unable to respond to these signals. Therefore, examination of the expression profiles of the wild type versus the ΔpqsR mutant should identify a combination of HHQ- and PQS-regulated genes. Lastly, the inclusion of the ΔpqsE mutant expression profile should assist in identifying specifically HHQ-dependent genes, as the ΔpqsE mutant produces both PQS and HHQ but lacks the PQS-dependent response mediated by PqsE (18). Thus, when comparing the three profiles, HHQ-dependent candidates will be similarly expressed in both the wild type and the ΔpqsE mutant while inversely expressed in the ΔpqsR mutant.

The microarray data comparing the wild-type strain to the ΔpqsE and ΔpqsR mutants were retrieved from the public GEO database (GEO number GSE17147) (28) and reanalyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The expression of the pqs genes served as an internal control for this data set; these genes were upregulated in both the wild-type strain and the ΔpqsE mutant, but they were downregulated in the ΔpqsR mutant (Fig. 3A). This finding is consistent with published reports wherein PqsR (MvfR), together with PQS or HHQ, can directly act as a positive regulator of the pqsABCDE and phnAB genes (50, 56). In addition to the pqs genes, a set of phenazine biosynthesis genes (phzG, phzF, phzD, phzC, and phzS) emerged as candidate HHQ-dependent genes (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

HHQ-dependent candidate genes. (A) Reanalysis of a previous microarray data set (GEO number GSE17147) as a heat map comparing global gene expression patterns among the wild-type strain and the ΔpqsE and ΔpqsR mutants. Genes of interest are highlighted in the box to the right. See Materials and Methods for the statistical parameters. The key in the upper right of the panel shows the relative differential expression corresponding to the colors in the heat map. The gene names corresponding to the names from strain P. aeruginosa PAO1 are shown, because this is the strain studied in the original analysis (11, 28). (B) Relative expression of the phzA gene (±standard deviation [SD]; n = 6); (C) relative expression of the phzG gene (±SD). For the plots shown in panels B and C, picograms (pg) of input DNA are plotted versus the strain tested.

Prior to testing the downstream candidates (i.e., phz genes) for swarming phenotypes, the expression levels of these candidate genes were examined via qRT-PCR. Here, we used RNA extracted from strains grown on swarm motility plates containing arginine, thus using the growth conditions identical to those used for all the phenotypic assays in this report. For this set of experiments, we examined the expression levels of the phzA and phzG genes in the wild-type strain and the ΔpqsA, ΔpqsH, ΔpqsR, and ΔphzA1-G1 ΔphzA2-G2 (Δphz) (13) mutants. Consistent with our microarray analysis, the wild-type strain, producing both PQS and HHQ molecules, demonstrated the highest level of transcripts for the phzA and phzG genes, while the ΔpqsH mutant consistently showed only ∼25% of the wild-type expression levels (Fig. 3B and C), indicating that expression of phzA and phzG genes are at least partially PQS dependent under these conditions. However, the lack of swarming by the ΔpqsH mutant suggests that even this decreased phz gene expression is still sufficient to repress swarming.

We also examined the expression of phzA and phzG transcripts in both ΔpqsA and ΔpqsR mutants, which served as PQS/HHQ-deficient and PQS/HHQ-unresponsive controls, respectively. Expression of the phzA and phzG genes was reduced >93% under these conditions for both the ΔpqsA and ΔpqsR mutants, a finding consistent with the microarray data. Based on the swarm phenotype of these mutants, we suggest that this marked reduction in expression of the phz biosynthetic gene cluster is sufficient to relieve phenazine-dependent repression of swarming (see below). Finally, as expected, no phzA or phzG gene transcript was detected in the Δphz mutant, which is deleted for both phz operons (13).

Thus, our microarray and qRT-PCR data support the HHQ-dependent induction of phenazine gene expression under these conditions and suggest that phenazines may mediate the ability of arginine to repress swarming motility.

Phenazines repress swarming on arginine medium.

Based on our microarray and qRT-PCR data, we hypothesized that phenazines might be required for swarm repression on arginine medium. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the swarming motility of the phenazine-null Δphz mutant (13) on arginine medium. The Δphz mutant demonstrated swarming on arginine medium, which resembled the ΔpqsA mutant phenotype (Fig. 4A).

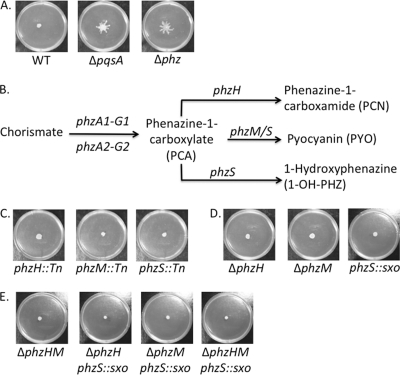

Fig. 4.

Phenazine-1-carboxylate (PCA) represses swarming motility. (A) Representative swarm phenotypes of the wild type (WT) and the ΔpqsA and ΔphzA1-G1 ΔphzA2-G2 (Δphz) mutants. (B) Simplified scheme of the phenazine biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa PA14. Genes involved are indicated above the arrows, and known phenazines produced by this organism are shown. (C) Representative swarm phenotypes of the phzH::Tn, phzM::Tn, and phzS::Tn mutants; (D) representative swarm phenotypes of the single mutants: ΔphzH, ΔphzM, and phzS::sxo mutants; (E) representative swarm phenotypes of double and triple mutants involved in the synthesis of terminal phenazines: ΔphzHM, ΔphzH phzS::sxo, ΔphzM phzS::sxo, and ΔphzHM phzS::sxo mutants.

Proteins encoded by the phenazine biosynthesis operons (phzA1-G1 phzA2-G2) synthesize phenazine-1-carboxylate (PCA), which can be converted into terminal phenazines, such as phenazine-1-carboxamide (PCN), pyocyanin (PYO), or 1-hydroxyphenazine (1-OH-PHZ) (Fig. 4B). Because the Δphz mutant lacks production of all phenazines, we sought to identify the specific phenazine(s) responsible for the repression of swarming motility on arginine medium. We tested strains with mutations in the genes responsible for converting PCA into the three terminal phenazines, phzH, phzM, and phzS, for their impacts on swarming motility. The corresponding transposon mutants (29) in any of these three genes failed to derepress swarming motility on arginine medium (Fig. 4C).

Consistent with the transposon mutant data, the ΔphzH and ΔphzM deletion strains and the single-crossover (SXO) phzS mutant were unable to swarm on the arginine medium (Fig. 4D). For reasons we do not understand, we were unable to delete the phzS gene via allelic exchange; hence, we have used the SXO mutant in all the studies described here. Collectively, these results suggest that PCA, but not the PCA derivatives PYO, 1-OH-PHZ, or PCN, is responsible for swarm repression. It is important to note that PYO is secreted at levels similar to PCA levels (13); thus, our observations are likely not due to different levels of the phenazines secreted. Alternatively, the terminal phenazines may have redundant function(s) in repressing swarming motility on arginine medium.

To address these two hypotheses, double and triple mutants were created: the ΔphzHM, ΔphzH phzS::sxo, ΔphzM phzS::sxo, and ΔphzHM phzS::sxo mutants. As with the swarm phenotypes of the single mutants highlighted in Fig. 4D, double and triple mutants perturbed for terminal phenazine biosynthesis were all still repressed for swarming on arginine medium (Fig. 4E). In sum, the data presented in Fig. 4 support the hypothesis that PCA is responsible for repressing swarm motility on arginine medium.

Cross-complementation of phenazines restore swarm repression by arginine.

Because the lack of phenazines derepresses swarming motility on arginine medium (Fig. 4A), the reintroduction of phenazines should repress swarming motility. Phenazines are redox-active compounds that are secreted by P. aeruginosa into the extracellular milieu (39, 51). Thus, we asked if phenazines provided in trans from other strains could repress swarm motility in a Δphz mutant, akin to the experiments described above wherein HHQ is provided in trans to the Δpqs mutants.

We performed the previously described cross-complementation experiment wherein the Δphz mutant was mixed with other strains in a 1:1 ratio. When the mixture lacked a phenazine-producing strain (e.g., ΔpqsA, -B, -D, and -R and ΔphnAB mutants), swarming motility was observed, whereas the inclusion of a phenazine-producing strain (e.g., the wild-type strain or the ΔpqsH mutant) repressed swarming motility on arginine medium (Fig. 5A and Table 4). Thus, it appears phenazines can be transferred between cells to repress swarming motility on arginine medium. Furthermore, the observation that the ΔlasR rhlR::tetR double mutant can repress swarming by the Δphz strain (Fig. 5A) suggests that strains lacking the Las and Rhl quorum-sensing systems still produce at least some phenazines.

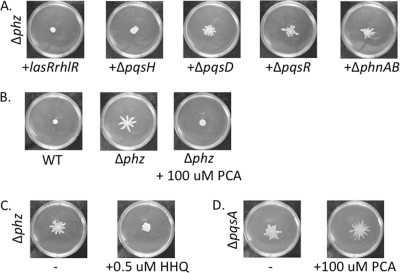

Fig. 5.

PCA-dependent and -independent swarm repression. (A) Representative swarm phenotypes when the ΔphzA1-G1 ΔphzA2-G2 (Δphz) mutant is coinoculated with other mutants (mutant genotype specified). Also see Table 4. (B) Representative swarm phenotypes of the wild-type strain and the ΔphzA1-G1 ΔphzA2-G2 (Δphz) mutant with or without exogenous 100 μM PCA; (C) representative swarm phenotypes of the Δphz mutant with or without exogenous 0.5 μM HHQ; (D) representative swarm phenotypes of the ΔpqsA mutant with or without exogenous 100 μM PCA.

Table 4.

Swarming by the ΔphzA1-G1 ΔphzA2-G2 mutant can be repressed by PCA-producing strains

| Strain | Swarming phenotype by the ΔphzA1-G1 ΔphzA2-G2 mutant |

|---|---|

| WT | − |

| ΔlasR mutant | − |

| ΔrhlR mutant | − |

| ΔlasR ΔrhlR mutant | − |

| ΔpqsA mutant | + |

| ΔpqsB mutant | + |

| ΔpqsD mutant | + |

| ΔpqsE mutant | − |

| ΔpqsH mutant | − |

| ΔpqsR mutant | + |

| ΔphnAB mutant | + |

−, negative swarming phenotype (e.g., no swarming); +, positive swarming phenotype. Phenotypes were scored based on observed tendril formation on at least five replicate plates.

PCA represses swarming on arginine medium.

Data presented in Fig. 4 and 5A suggest that PCA, and not terminal phenazines, may be important in repressing swarming motility on arginine medium. To directly address this hypothesis, chemically synthesized PCA (100 μM; Princeton BioSciences, Princeton, NJ) was added exogenously to the arginine swarm medium. The addition of PCA was sufficient to repress the swarming motility of the Δphz mutant on arginine medium (Fig. 5B).

The data presented thus far are consistent with a simple model wherein HHQ is required for PCA production, and PCA in turn represses swarming motility. There are two predictions that grow from this simple model. First, the addition of HHQ to a mutant blocked in PCA production should no longer repress swarming motility. Second, the addition of PCA to a mutant lacking HHQ should still repress swarming motility. To our surprise, neither of these predictions was borne out. First, the addition of 0.5 μM HHQ to the Δphz mutant still repressed swarming motility despite the inability of this mutant to produce PCA (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the ΔpqsA mutant (which is unable to produce HHQ) still swarmed upon the addition of 100 μM PCA (Fig. 5D). Combined, these data suggest that there may be an HHQ-dependent, PCA-independent regulatory pathway for repressing swarming motility on arginine also operating in this microbe, indicating a complex mechanism of swarming regulation.

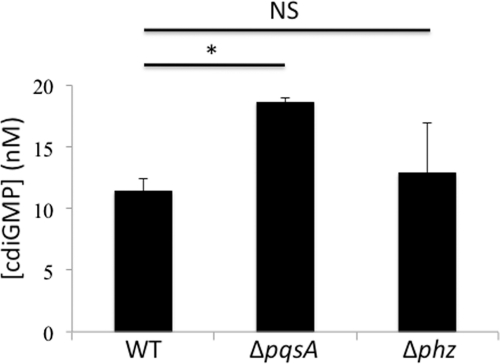

Mutations in the pqsA or phz genes do not alter pools of c-di-GMP.

Our group has previously shown a role for c-di-GMP in regulating group behaviors, including swarming motility (25, 32, 33). It is possible that the swarming motility phenotype we observed in both the Δpqs and Δphz mutants on the arginine medium can be attributed to a reduction in their intracellular c-di-GMP levels. To address this issue, we quantified and compared the intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations among the wild-type strain and the ΔpqsA and Δphz mutants via a previously described LC-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method (33, 34).

Quantification of the intracellular c-di-GMP pool demonstrated comparable c-di-GMP levels in the three strains (Fig. 6), with a small but statistically significant increase in the c-di-GMP level in the ΔpqsA mutant compared to that in the wild-type strain. There was no significant difference between the wild-type strain and the Δphz mutant. Therefore, our data suggest that derepression of swarming motility in the ΔpqsA and Δphz mutants is independent of a decrease in the cellular level of c-di-GMP.

Fig. 6.

Mutations in PQS and phenazine biosynthesis do not reduce c-di-GMP levels. Quantification of the global intracellular pool of c-di-GMP for the wild-type strain and the ΔpqsA and Δphz mutants measured via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (±SD; n = 6). *, P < 0.03; NS, not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

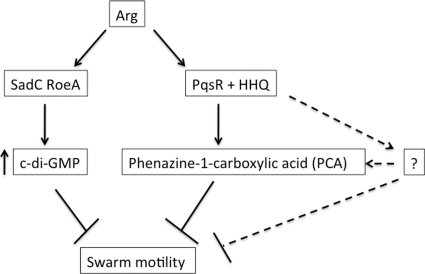

In this report, we sought to study the regulation of swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We exploited arginine-supplemented swarm medium, which represses swarming, to perform a transposon mutagenesis screen to identify mutants derepressed for swarming motility, and a candidate pqsA::Tn mutant was identified. Subsequent genetic analyses demonstrated a role for HHQ in repression of swarming motility in response to arginine. Combined microarray reanalysis, qRT-PCR, and mutational studies indicated that PCA is one candidate for an HHQ-dependent downstream regulator of swarm repression. Previously published studies support the possibility that HHQ, together with PqsR, likely directly positively regulates the expression of the phenazine biosynthetic genes (56). However, the mechanism by which PCA regulates swarming remains to be identified. Furthermore, our data also support the existence of an HHQ-dependent, PCA-independent pathway for repression of swarming motility. Finally, our data indicate that HHQ/PCA-mediated swarm repression is c-di-GMP independent. A model summarizing these findings is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Proposed model for swarming motility on arginine medium. The repression of swarming motility by arginine requires functional diguanylate cyclases (DGCs, SadC, and RoeA) as well as PqsR and HHQ (solid lines and arrows). A distinct HHQ-dependent but PCA-independent pathway is also predicted (dotted lines and arrows). Arrows and lines indicate genetic relationships only.

Identification of HHQ-dependent downstream targets was achieved by reanalyzing a previous microarray experiment (GEO number GSE17147). We note that the strains used for this microarray experiment were cultured in LB medium, and their RNA was extracted at OD600s of 2.5 (wild type and the ΔpqsR mutant) and 3.0 (the ΔpqsE mutant) (11, 28). These conditions are different from our swarm experimental conditions (M8 medium, incubated ∼24 h). Therefore, we verified the expression of the microarray-derived candidate phz genes (phzA and phzG) using total RNA extracted from cells scraped from swarm agar plates. The ΔpqsH mutant, which is not capable of swarming motility on arginine medium, showed only 25% of the wild-type level for phz gene expression. Because the ΔpqsH mutant lacks the monooxygenase for HHQ-to-PQS conversion (12, 46), the remaining expression of the phz genes can be attributed to HHQ, and this residual level of phz gene expression is apparently sufficient to maintain repression of swarming motility under these conditions. Mutants that either fail to produce HHQ (the ΔpqsA mutant) or cannot respond to HHQ (the ΔpqsR mutant) showed very low relative expression of the phz genes compared to that of the wild type. Therefore, we propose that while both PQS and HHQ contribute to full expression of the phz genes, the HHQ-mediated expression of these genes is essential for the observed swarming phenotype. And although not explored here, we recognize that other quinolone molecules are produced via HHQ, such as 4Q-N-oxides (12, 15, 43, 52), which may also contribute to the expression of phz genes and/or repressing swarming motility on arginine. Deducing the effects of other quinolone molecules will be a topic for future investigation.

Importantly, we note that the genes in both phz operons share highly identical sequences (>97%) at the DNA level. Therefore, while our expression data likely reflect the sum of the expression of the two sets of phz genes (phzA1-G1 and phzA2-G2), it is possible that the two phz operons differentially contribute to repression of swarming. For example, Gallagher et al. (18) showed differential expression between phz1 and phz2 expression, with phz2 expressed independently of PQS and the PqsE protein, whereas phz1 expression was dependent on both. Based on this published work and our studies, we hypothesize that PqsR/HHQ may regulate the phz2 gene cluster.

Proteins encoded by the two phz operons synthesize the phenazine PCA. PCA is then converted to any of the three terminal phenazines (1-OH-PHZ, PCN, and PYO) by the activities of the PhzH, PhzM, and/or PhzS proteins (Fig. 4B). Similar to QS signals, phenazines are implicated in regulatory roles, such as impacting gene expression (13) and modulating group behaviors (14, 41). In fact, Ramos et al. (41) recently showed that the Δphz mutant was a hyperswarmer on a minimal glucose medium and, furthermore, that the addition of 100 μM exogenous PCA could partially repress the hyperswarming phenotype of this mutant. Our work presented here is consistent with these findings. Interestingly, the Δphz mutant showed a hyperswarming phenotype compared to the wild type on glucose medium (41) (data not shown) as well as on arginine medium (Fig. 4), indicating that phenazines like PCA may modulate swarming motility in a number of environments. We are currently focused on identifying the potential target(s) of PCA important for controlling swarming motility.

With regard to the ΔsadC ΔroeA mutant, we previously showed that this double mutant is a hyperswarmer with a decreased global pool of c-di-GMP (33); therefore, it was possible that the HHQ-mediated swarm repression was due to a reduction in intracellular c-di-GMP levels. However, our data suggest that HHQ-dependent regulation and c-di-GMP-dependent regulation of swarm motility define distinct pathways (Fig. 6 and 7), as global c-di-GMP pools of both ΔpqsA and Δphz mutants show levels that are similar to or higher than those of the wild-type strain. Meanwhile, we see no consistent or significant changes in phz gene expression in the wild type versus the ΔsadC ΔroeA double mutant (data not shown). In sum, we believe our study supplements the growing literature demonstrating signaling and regulatory properties of HHQ and PCA (12, 15, 43, 52).

This report originated from investigating the effects of arginine on swarming motility. Using arginine-supplemented swarm medium, we demonstrated that HHQ, which can be converted to PQS by the PqsH protein, is a modulator of swarm motility. Previous studies demonstrated an ∼5-fold-higher PQS production level when P. aeruginosa PA14 was grown in a CF sputum specimen than in a standard laboratory (MOPS) medium (38). In the synthetic CF sputum medium (SCFM) described by Palmer and colleagues (37), P. aeruginosa PA14 also produced ∼4-fold more PQS than in MOPS medium (37, 38). Thus, HHQ levels may be higher in the CF lung or CF-like environmental conditions, thereby contributing to the repression of swarm motility. Furthermore, phenazine levels were also shown to be elevated in P. aeruginosa grown in SCFM (37, 38), which, based on our findings, would likely repress swarm motility. Arginine is present in the CF lung at ∼0.3 mM (37); therefore, the arginine-dependent, HHQ- and phenazine-mediated repression of swarming motility may in part explain why P. aeruginosa in the CF lung might favor biofilm formation over swarming motility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Hogan and D. K. Newman for providing mutant strains and D. Hogan for advice and discussions in preparing the manuscript. We also thank the MSU Mass Spectrometry Facility for LC-MS/MS measurements.

This work was supported by NIH grant number R01A1003256 to G.A.O. J.T.H. is supported by an MRC strategic priority studentship awarded to M.W. and D.R.S. Work in the lab of M.W. is supported by the United Kingdom BBSRC.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bernier S. P., Ha D. G., Khan W., Merritt J. H., O'Toole G. A. 2011. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface-associated group behaviors by individual amino acids through c-di-GMP signaling. Res. Microbiol. 162:680–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burke D., Dawson D., Stearns T. 2000. Methods in yeast genetics: a Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caetano-Anolles G. 1993. Amplifying DNA with arbitrary oligonucleotide primers. PCR Methods Appl. 3:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caiazza N. C., Merritt J. H., Brothers K. M., O'Toole G. A. 2007. Inverse regulation of biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189:3603–3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caiazza N. C., Shanks R. M., O'Toole G. A. 2005. Rhamnolipids modulate swarming motility patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 187:7351–7361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calfee M. W., Shelton J. G., McCubrey J. A., Pesci E. C. 2005. Solubility and bioactivity of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal are increased by a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-produced surfactant. Infect. Immun. 73:878–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Camilli A., Bassler B. L. 2006. Bacterial small-molecule signaling pathways. Science 311:1113–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cao H., et al. 2001. A quorum sensing-associated virulence gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes an LysR-like transcription regulator with a unique self-regulatory mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:14613–14618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi K. H., et al. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2:443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cugini C., Morales D. K., Hogan D. A. 2010. Candida albicans-produced farnesol stimulates Pseudomonas quinolone signal production in LasR-defective Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Microbiology 156:3096–3107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deziel E., et al. 2005. The contribution of MvfR to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and quorum sensing circuitry regulation: multiple quorum sensing-regulated genes are modulated without affecting lasRI, rhlRI or the production of N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones. Mol. Microbiol. 55:998–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deziel E., et al. 2004. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinolines (HAQs) reveals a role for 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline in cell-to-cell communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:1339–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dietrich L. E., Price-Whelan A., Petersen A., Whiteley M., Newman D. K. 2006. The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1308–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dietrich L. E., Teal T. K., Price-Whelan A., Newman D. K. 2008. Redox-active antibiotics control gene expression and community behavior in divergent bacteria. Science 321:1203–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diggle S. P., et al. 2007. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-quinolone signal molecules HHQ and PQS play multifunctional roles in quorum sensing and iron entrapment. Chem. Biol. 14:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dubern J. F., Diggle S. P. 2008. Quorum sensing by 2-alkyl-4-quinolones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacterial species. Mol. Biosyst. 4:882–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farrow J. M., III, et al. 2008. PqsE functions independently of PqsR-Pseudomonas quinolone signal and enhances the rhl quorum-sensing system. J. Bacteriol. 190:7043–7051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gallagher L. A., McKnight S. L., Kuznetsova M. S., Pesci E. C., Manoil C. 2002. Functions required for extracellular quinolone signaling by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 184:6472–6480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harmsen M., Yang L., Pamp S. J., Tolker-Nielsen T. 2010. An update on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation, tolerance, and dispersal. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 59:253–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hogan D. A., Kolter R. 2002. Pseudomonas-Candida interactions: an ecological role for virulence factors. Science 296:2229–2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hogan D. A., Vik A., Kolter R. 2004. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule influences Candida albicans morphology. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1212–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huse H., Whiteley M. 2011. 4-Quinolones: smart phones of the microbial world. Chem. Rev. 111:152–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Irizarry R. A., et al. 2003. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4:249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kohler T., Curty L. K., Barja F., van Delden C., Pechere J. C. 2000. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J. Bacteriol. 182:5990–5996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuchma S. L., et al. 2010. Cyclic-di-GMP-mediated repression of swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the pilY1 gene and its impact on surface-associated behaviors. J. Bacteriol. 192:2950–2964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuchma S. L., et al. 2007. BifA, a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189:8165–8178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kulasakara H., et al. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:2839–2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lesic B., Starkey M., He J., Hazan R., Rahme L. G. 2009. Quorum sensing differentially regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa type VI secretion locus I and homologous loci II and III, which are required for pathogenesis. Microbiology 155:2845–2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liberati N. T., et al. 2006. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:2833–2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mashburn L. M., Whiteley M. 2005. Membrane vesicles traffic signals and facilitate group activities in a prokaryote. Nature 437:422–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGrath S., Wade D. S., Pesci E. C. 2004. Dueling quorum sensing systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa control the production of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Merritt J. H., Brothers K. M., Kuchma S. L., O'Toole G. A. 2007. SadC reciprocally influences biofilm formation and swarming motility via modulation of exopolysaccharide production and flagellar function. J. Bacteriol. 189:8154–8164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Merritt J. H., et al. 2010. Specific control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface-associated behaviors by two c-di-GMP diguanylate cyclases. mBio 1(4):e00183–10 doi:10.1128/mBio.00183-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newell P. D., Yoshioka S., Hvorecny K. L., Monds R. D., O'Toole G. A. 2011. A systematic analysis of diguanylate cyclases that promote biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. J. Bacteriol. 193:4685–4698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ochsner U. A., Reiser J., Fiechter A., Witholt B. 1995. Production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhamnolipid biosurfactants in heterologous hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3503–3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Toole G. A., Kolter R. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:449–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palmer K. L., Aye L. M., Whiteley M. 2007. Nutritional cues control Pseudomonas aeruginosa multicellular behavior in cystic fibrosis sputum. J. Bacteriol. 189:8079–8087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Palmer K. L., Mashburn L. M., Singh P. K., Whiteley M. 2005. Cystic fibrosis sputum supports growth and cues key aspects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa physiology. J. Bacteriol. 187:5267–5277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Price-Whelan A., Dietrich L. E., Newman D. K. 2007. Pyocyanin alters redox homeostasis and carbon flux through central metabolic pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189:6372–6381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rahme L. G., et al. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268:1899–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramos I., Dietrich L. E., Price-Whelan A., Newman D. K. 2010. Phenazines affect biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in similar ways at various scales. Res. Microbiol. 161:187–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rampioni G., et al. 2010. Transcriptomic analysis reveals a global alkyl-quinolone-independent regulatory role for PqsE in facilitating the environmental adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to plant and animal hosts. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1659–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reen F. J., et al. 2011. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS), and its precursor HHQ, modulate interspecies and interkingdom behaviour. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 77:413–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reimmann C., et al. 2002. Genetically programmed autoinducer destruction reduces virulence gene expression and swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbiology 148:923–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sanderson K., Wescombe L., Kirov S. M., Champion A., Reid D. W. 2008. Bacterial cyanogenesis occurs in the cystic fibrosis lung. Eur. Respir. J. 32:329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schertzer J. W., Brown S. A., Whiteley M. 2010. Oxygen levels rapidly modulate Pseudomonas aeruginosa social behaviours via substrate limitation of PqsH. Mol. Microbiol. 77:1527–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shanks R. M., Caiazza N. C., Hinsa S. M., Toutain C. M., O'Toole G. A. 2006. Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based molecular tool kit for manipulation of genes from Gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5027–5036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Simon R., Priefer U., Puhler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1:784–791 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vander Wauven C., Pierard A., Kley-Raymann M., Haas D. 1984. Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants affected in anaerobic growth on arginine: evidence for a four-gene cluster encoding the arginine deiminase pathway. J. Bacteriol. 160:928–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wade D. S., et al. 2005. Regulation of Pseudomonas quinolone signal synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 187:4372–4380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang Y., Kern S. E., Newman D. K. 2010. Endogenous phenazine antibiotics promote anaerobic survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa via extracellular electron transfer. J. Bacteriol. 192:365–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang Y., et al. 2011. Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid promotes bacterial biofilm development via ferrous iron acquisition. J. Bacteriol. 193:3606–3617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Williams P., Camara M. 2009. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Woodman M. E. 2008. Direct PCR of intact bacteria (colony PCR). Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 9:A.3D.1–A.3D.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Worlitzsch D., et al. 2002. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Invest. 109:317–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xiao G., et al. 2006. MvfR, a key Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity LTTR-class regulatory protein, has dual ligands. Mol. Microbiol. 62:1689–1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xiao G., He J., Rahme L. G. 2006. Mutation analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa mvfR and pqsABCDE gene promoters demonstrates complex quorum-sensing circuitry. Microbiology 152:1679–1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]