Abstract

The TetR family of transcriptional regulators is ubiquitous in bacteria, where it plays an important role in bacterial gene expression. Streptococcus mutans, a Gram-positive pathogen considered to be the primary etiological agent in the formation of dental caries, encodes at least 18 TetR regulators. Here we characterized one such TetR regulator, SMU.1349, encoded by the TnSmu2 operon, which appeared to be acquired by the organism via horizontal gene transfer. SMU.1349 is transcribed divergently from the rest of the genes encoded by the operon. By the use of a transcriptional reporter system and semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), we demonstrated that SMU.1349 activates the transcription of several genes that are encoded within the TnSmu2 operon. Gel mobility shift and DNase I footprinting assays with purified SMU.1349 protein demonstrated binding to the intergenic region between SMU.1349 and the TnSmu2 operon; therefore, SMU.1349 is directly involved in gene transcription. Using purified S. mutans RpoD and Escherichia coli RNA polymerase, we also demonstrated in an in vitro transcription assay that SMU.1349 could activate transcription from the TnSmu2 operon promoter. Furthermore, we showed that SMU.1349 could also repress transcription from its own promoter by binding to the intergenic region, suggesting that SMU.1349 acts as both an activator and a repressor. Thus, unlike most of the TetR family proteins, which generally function as transcriptional repressors, SMU.1349 is unique in that it can function as both.

INTRODUCTION

In their natural habitats, bacteria are constantly exposed to various environmental fluxes, including severe nutrient limitation, fluctuations in pH and temperature, and changes in oxidative and osmotic tensions (20). In order to survive adverse environmental conditions, bacteria mount a wide range of rapid and adaptive responses. These responses are generally mediated by regulatory proteins, which modulate transcription, translation, or other events in gene expression so that the physiological responses are appropriate to the environmental changes. In some cases, adaptive responses are controlled by the so-called “two-component” signal transduction systems (TCS). The TCS typically consists of a membrane-bound sensor histidine kinase and a cytoplasmic DNA binding response regulator, with a common biochemical mechanism involving phosphoryl group transfer between these two distinct protein components (34). However, most often the adaptive responses are induced by various stand-alone transcriptional regulators, which are two-domain proteins with a signal-receiving domain and a DNA-binding domain (17, 24). Most of the transcriptional regulators contain the helix-turn-helix (HTH) signature motif, which is used for binding to their target DNA sequences. Based on sequence similarity as well as on structural and functional characteristics, these stand-alone regulators are classified into multiple families (1, 32). Among them, the tetracycline repressor (TetR) family transcriptional regulators constitute the third most frequently occurring transcriptional regulator family found in bacteria (28).

The TetR family is named after the transcriptional regulators that control the expression of the tet genes, whose product confers resistance to tetracycline (13, 21, 32). However, TetR family proteins are also involved in various other important biological processes, such as biofilm formation, biosynthesis of antibiotics, catabolic pathways, multidrug resistance, nitrogen fixation, stress responses, and the pathogenicity of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (32). All the proteins belonging to the TetR family share a high degree of sequence similarity at the DNA-binding domain located at the N-terminal region.

Generally, the TetR family proteins function as homodimers, with each monomer containing an N-terminal DNA-binding domain and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain that takes part in dimerization. Escherichia coli TetR and Staphylococcus aureus QacR are the best-characterized TetR family proteins (32). The E. coli TetR protein binds to two DNA operator sites, causing transcriptional repression of its own gene as well as the divergently transcribed tetA gene, which encodes a transporter for tetracycline. Tetracycline binds to the C-terminal domain of TetR, leading to a conformational change in the DNA-binding domain, and renders the protein inactive for DNA binding (15). Therefore, when tetracycline is present, it induces the expression of TetR-regulated genes (27, 32). Similarly, QacR represses the transcription of the membrane protein QacA, a multidrug efflux transporter (11). Multiple structurally dissimilar cationic lipophilic compounds, which are pumped out of the cell by QacA, bind to QacR and change its conformation (11, 25). The majority of the TetR family proteins characterized act as repressors by binding to the target operators, and the repression is relieved by the binding of a small ligand to their C-terminal ligand-binding and dimerization domains.

More recently, a few TetR family proteins have been shown to act as transcription activators (9, 14, 26, 31). The most notable of these is the Vibrio harveyi master quorum-sensing regulator, LuxR (31). While LuxR represses the expression of some genes, it also functions as an activator of the lux operon (encoding luciferase) and other quorum-sensing target genes (36). DhaS, another TetR family protein, activates the dha operon, which encodes dihydroxyacetone (Dha) kinases (9, 33). TetR-mediated transcription activation could occur either through direct recruitment of RNA polymerase, through DNA bending, or through interference with other transcription repressors. So far, however, no mechanism has been described to explain the gene activation mediated by TetR family proteins.

Streptococcus mutans, which is part of the human oral cavity flora, is considered to be the primary etiological agent in the formation of dental caries (12, 22). S. mutans is also a leading cause of bacterial endocarditis: more than 14% of viridans group streptococcus-induced endocarditis cases are triggered by S. mutans infection (16). The capacity of S. mutans to persist and to maintain a dominant presence in the oral cavity is partially due to its ability to adapt and respond to a variety of adverse growth-limiting conditions (20). Like those in other bacteria, adaptive responses in S. mutans are regulated by transcription factors, many of which are TetR family proteins.

The present study was undertaken to evaluate the role played by one such TetR family regulator, SMU.1349, in modulating gene expression. This regulator, which was originally identified by Wu and colleagues (37), is present on TnSmu2, a genomic island of S. mutans. Our study indicates that SMU.1349 can act both as an activator and as a repressor of gene transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strain DH5α was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented (when necessary) with ampicillin (50 or 100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml). S. mutans strain UA159 and its derivatives were grown in Todd-Hewitt medium (BBL; Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY). The pH of THY medium was routinely adjusted with HCl to 7.2 prior to sterilization. The growth of the S. mutans cultures was monitored using a Klett-Summerson colorimeter with a red filter. When necessary, erythromycin (5 μg/ml), kanamycin (300 μg/ml), or spectinomycin (300 μg/ml) was added to the liquid or solid growth medium.

Table 1.

Streptococcus mutans strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or purpose | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| UA159 | Wild type, serotype C | R. A. Burne, University of Florida |

| IBSC07 | UA159 ΔSMU.1349 | This study |

| IBSC12 | UA159::PSMU.1349-gusA; Kmr | This study |

| IBSC14 | UA159::PpsaA-gusA; Kmr | This study |

| IBSC16 | IBSC07::PSMU.1349-gusA; Kmr | This study |

| IBSC18 | IBSC07::PpsaA-gusA; Kmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pASK-IBA43+ | Vector plasmid for protein expression | IBA GmbH, Germany |

| pIB107 | Plasmid containing gusA for reporter assay; Kmr | 6 |

| pIB184 | Shuttle plasmid containing P23 promoter; Emr | 5 |

| pIBC33 | pASK-IBA43::SMU.1349 for overexpression; Apr | This study |

| pIBC55 | pIB184::SMU.1349 for complementation; Emr | This study |

Construction of SMU.1349-deleted and -complemented strains.

For the construction of a clean knockout mutant of SMU.1349 from the S. mutans UA159 genome, a Cre-loxP-based method was used according to a protocol described previously (4). Regions of approximately 1 kb upstream and downstream of the SMU.1349 open reading frame (ORF) were amplified from S. mutans UA159 chromosomal DNA using the primer combinations listed in Table 2. Two fragments were then digested with EcoRV, followed by ligation and cloning into the pGEM-T Easy cloning vector (Promega) to create pIBC49. A kanamycin (Km)-resistant cassette with flanking loxP sites was amplified from pUC4ΩKm (29) using primers lox71-Km-F and lox66-Km-R (4) and was cloned into EcoRV-digested pIBC49 to generate pIBC51. Plasmid pIBC51 was linearized with NotI and was transformed into S. mutans UA159. Transformants were selected on THY medium plates containing Km; one such transformant was named IBSC05. The loxP-Km cassette was eliminated from the IBSC05 chromosome by transformation with pCrePA as described previously (2). The clean SMU.1349 deletion mutant was named IBSC07.

Table 2.

List of oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Bam-Smu1349-F1 | GGATCCATGACTAAGGGAACAAGGG | Expression of SMU.1349 |

| Nco-Smu1349-R1 | CCATGGTTATTGGTTTCTCTTCTT | Expression of SMU.1349 |

| Smu1349 N-Flnk-F | GATTTTGTCCGCTTCGAACATGAATG | Deletion of SMU.1349 |

| Smu1349 N-Flnk-RV | CCCGGGATATCAAAACCTTCCCTCTCCTTACTT | Deletion of SMU.1349 |

| Smu1349 C-Flnk-R | TGGATGCAAAATGCGCATCGTT | Deletion of SMU.1349 |

| Smu1349 C-Flnk-RV | CCCGGGATATCTTAGACTGAAGACAAAGCTCTT | Deletion of SMU.1349 |

| Bam-Smu1349out-F | GGATCCGACCATATATACTAATAGCAAGTTGC | Complementation/GusA fusion |

| Xho-Smu1349-R | GGCGCTCGAGTTATTGGTTTCTCTTCTTTTTA | Complementation/GusA fusion |

| PsaA RT F | CAGGAAATTGAAGCAGTAAAGCATG | qRT-PCR |

| PsaA RT R | CCCTTTGTTGTTCACCTCCTGA | qRT-PCR |

| Smu BacA F | ATGGAAATTTTATTTGAGCAAAATGAAACG | qRT-PCR |

| Smu BacA R | GCTATGTTCATCATTAATAGAACTAGC | qRT-PCR |

| Smu BacC F | AACCTCAAAATAAAATCGAAGAAACGC | qRT-PCR |

| Smu BacC R | GCTGTGGAAGAAGGATTAAATAGCTGA | qRT-PCR |

| Smu GyrA F1 | CTCTTCCAGATGTTCGCGATGG | qRT-PCR |

| Smu GyrA R1 | ACGGTAAAACTAAAGGTTCACG | qRT-PCR |

| Smu1349 out F | GACCATATATACTAATAGCAAGTTGC | EMSA/DPA |

| Smu1349 out R | AAAACCTTCCCTCTCCTTACTT | EMSA/DPA |

| Apa PsaA PF | TATAGGGCCCGAATCATAGTTTTAATATTAGATTAC | EMSA/DPA |

| Xho PsaA PR | CTGGCTCGAGCTTTTAAATTCAATAATGTTCATCTTTTC | EMSA, DPA, and GusA fusion |

| Bam PsaA F | GGATCCTGTGAAAGTATTTATTCTATAT | GusA fusion |

To complement SMU.1349, the full-length ORF was amplified from the UA159 chromosome along with 250 bp upstream containing its putative promoter region by using primers Bam-Smu1349-out-F and Xho-Smu1349-R (Table 2). The amplicon was digested with the BamHI and XhoI restriction enzymes and was cloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of the E. coli-Streptococcus shuttle vector pIB184 (5) to construct pIBC55. Plasmid pIBC55 was transformed to IBSC07 to make the complemented strain.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

S. mutans cultures grown to the mid-exponential-growth phase (70 Klett units) were processed for RNA isolation as described previously (4). RNA samples were quantified using a NanoDrop instrument. One microgram of RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis (at 42°C with a 1-h incubation) using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, CA). The reaction was terminated by incubating the reaction tubes at 70°C for 15 min, followed by treatment with RNase H (Invitrogen, CA) at 37°C for 20 min and purification of the cDNA using a PCR purification column (Qiagen).

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as described previously (10). Briefly, RNA samples were subjected to a one-tube quantitative SYBR green PCR assay using a Power SYBR green RNA kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI Prism 7000 LightCycler system (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 2. As an additional control for each primer set and RNA sample, the cDNA synthesis reaction was carried out in the absence of reverse transcriptase to verify that genomic DNA did not contaminate the RNA samples. The critical threshold cycle (CT) was defined as the cycle in which fluorescence was detectable above the background and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial number of RNA molecules. A standard curve was plotted for each primer set with CT values obtained from amplification of known quantities of DNA. The standard curve was used for transformation of the CT values to the relative number of cDNA molecules. The expression levels of all the genes tested by real-time RT-PCR were normalized using gyrA expression as an internal standard. No-template controls were also included in all real-time PCRs. The relative expression levels were calculated according to the method developed by Pfaffl (30). GraphPad Prism software was employed to analyze the experimental data. The data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD).

Construction of PSMU.1349-gusA and PSMU.1348-gusA reporter fusions.

To construct PSMU.1349 and PSMU.1348 reporter fusion strains, the putative promoter regions were amplified from UA159 chromosomal DNA using primers listed in Table 2. The amplicons were cloned into the BamHI and XhoI restriction sites of plasmid pIB107, which contains a promoterless gusA gene and can be used for integration at the SMU.1405 locus for single-copy reporter fusion as described previously (6). The reporter constructs pIBC59 and pIBC61, carrying PSMU.1349-gusA and PSMU.1348-gusA fusions, respectively, were linearized with the BglI restriction enzyme and were transformed into UA159 to create strains IBSC12 and IBSC14, respectively. The constructs were also transformed to the SMU.1349-deleted strain IBSC07 to construct IBSC16 and IBSC18, respectively (Table 1).

GusA assay.

For assaying β-glucuronidase (GUS; encoded by gusA)-specific activity, the reporter strains were grown in Klett flasks to mid-exponential phase (70 Klett units) in THY broth, and cell lysates were prepared as described previously (6). The GUS activity in the cell lysate was standardized by comparison to known concentrations of glucuronidase (Sigma). The protein concentration in the lysate was determined by the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad) method standardized against bovine serum albumin (BSA).

Purification of His-tagged SMU.1349 protein.

For overexpression of SMU.1349, the open reading frame was amplified using primers Bam-Smu1349-F1 and Nco-Smu1349R1 and was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector to create pICBC30. The open reading frame was then subcloned from pIBC30 into pASK-IBA43 (IBA) by using BamHI and NcoI digestion to construct an N-terminally His tagged plasmid, which was named pIBC33.

His-tagged SMU.1349 protein was purified by using a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) column (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein was dialyzed overnight against a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. The protein was purified to >95% homogeneity as determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis. The concentration of the protein was estimated using a Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

EMSA and DPA.

The interaction of SMU.1349 with its own promoter and the promoter of SMU.1348 was determined by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and DNase I protection assays (DPA) according to methods described previously (4). Briefly, primers Smu.1349F and Apa-Psa-PF were labeled with [γ-32P]dATP using T4-PNK (New England BioLabs [NEB]) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Labeled primers along with unlabeled primers Smu.1349R and Bam-Psa-PR were used to amplify the putative promoter regions of the SMU.1349 and SMU.1348 genes, respectively. For EMSA, each fragment (1 pmol) was incubated with increasing concentrations of 6×His-tagged SMU.1349 protein (28 to 140 pmol) in a binding buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 10 μg/ml poly(dI-dC), 5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2 · 6H2O, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 50% glycerol] for approximately 40 min at room temperature. Specific and nonspecific competition assays were also performed using a 20-fold molar excess of the cold promoter and PnlmA, respectively. Following incubation, 10 μl of the DNA-protein mixture was resolved in a 4% native polyacrylamide gel buffered with 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE), which was run at 100 V for 1 h 30 min. The gel was then dried, exposed to a phosphorimager plate, and developed using a FLA9000 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

For the DNase I protection assay, the promoter fragments incubated with SMU.1349 protein for EMSA were subjected to DNase I (Epicentre) digestion for 5 min, followed by ethanol precipitation as described previously (4). The samples were denatured and loaded onto an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and buffered with 0.5× TBE. The gel was run at 1,400 V until the bromophenol blue dye front reached the lower one-third of the gel. The gel was then dried and exposed to an imager plate, followed by analysis using a FLA9000 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

IVT assay.

An in vitro transcription (IVT) assay was performed to detect the effect of SMU.1349 on SMU.1348 transcription. The putative promoter region of the SMU.1348 gene was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the plasmid was named pIBC58. For the in vitro transcription runoff assay, either the linearized plasmid or the PSMU.1348 amplified from pIBC58 was used as a template. Approximately 200 ng of the PSMU.1348 template was preincubated with various concentrations of purified SMU.1349 protein (45 to 675 pmol) at 37°C for 20 min in a reaction buffer containing 66 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.9), 40 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM magnesium acetate, 5 mM DTT, and 300 ng/ml BSA. After incubation, 1 U of E. coli core RNA polymerase (Epicentre), 1 μg of the S. mutans sigma factor RpoD (8), and 2 U of RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen) were added, and incubation was continued for 5 min. Transcription was initiated by adding 2 mM ATP, 500 μM (each) CTP and GTP, and 40 μM UTP (final concentrations) with 5μCi of [α-32P]UTP (∼9,000 Ci/mmol) to the reaction mixture. Heparin (10 μg) was added to inhibit the reinitiation of transcription. The reaction was continued for 20 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of stop solution, followed by denaturation of the samples by heating at 90°C for 2 min. The samples were resolved in a 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer. The gel was dried, exposed to an imager plate, and analyzed using a FLA9000 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

SMU.1349 encodes a TetR family protein.

To identify TetR family proteins in the S. mutans UA159 genome, we used a modified Pfam hidden Markov model (HMM), profile PF00440 (3), as described by Ramos and colleagues (32). This sequence, which has 46 residues, was used as a query against the UA159 genome sequence. We obtained a total of 18 transcriptional factors whose length ranged from 98 to 217 amino acids (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). While most of these sequences were also found in NN2025, the only other S. mutans strain for which complete genome sequence information is available (23), we found four TetR family proteins that were unique to the UA159 genome (SMU.1027, SMU.1349, SMU.1361, and SMU.1585). Of these four regulators, the TnSmu2 genomic island encodes two, SMU.1349 and SMU.1361 (35, 37). Recently it was shown that TnSmu2 carries a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-polyketide synthase (PKS) gene cluster and is involved in the synthesis of an NPRS-PKS metabolite named mutanobactin A (18). Earlier we found that CovR, an orphan response regulator, positively regulates this gene cluster (10), which spans the region from SMU.1334 to SMU.1348. The gene cluster, originally named the smt operon (7), was subsequently designated the mub operon to reflect its role in mutanobactin A synthesis (37). We also observed that CovR binds directly to the intergenic region between SMU.1348 and SMU.1349 but activates only the smt operon. Because SMU.1349 is a TetR homolog and because the majority of the TetR family proteins act as repressors, we speculated that SMU.1349 might play a role in the expression of this operon. Of note, SMU.1349 is also designated MubR; however, another protein from strain UA140 with homology to a TCS response regulator is also designated MubR (37). Therefore, to distinguish between these two different types of regulators, we chose to use the designation SMU.1349 for this TetR family protein.

SMU.1349 activates the TnSmu2 operon.

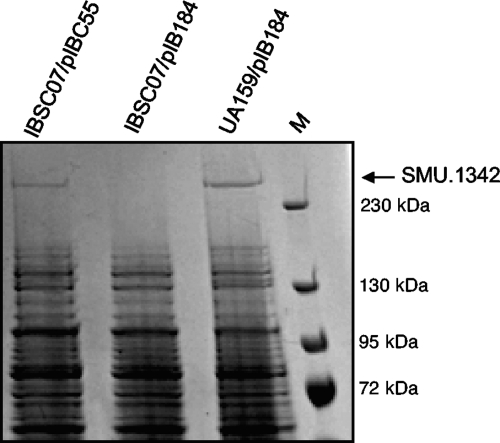

To investigate the role of SMU.1349 in S. mutans UA159, an unmarked clean deletion mutant was constructed using the Cre-loxP-based gene deletion system. The growth rates of the wild-type and ΔSMU.1349 mutant (IBSC07) strains in THY broth were essentially similar (data not shown). Next, we determined the total cellular protein profiles of the wild-type (UA159) and mutant (IBSC07) strains, each containing the shuttle plasmid pIB184 (UA159/pIB184 and IBSC07/pIB184, respectively), by resolution by SDS-PAGE with a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient. As shown in Fig. 1, in the crude cell lysates, prepared from exponentially growing cultures, a band that migrates above the largest marker (230 kDa) appears to be expressed in UA159/pIB184 but is absent in IBSC07/pIB184. This band was also visible in the stationary-phase culture lysates from UA159/pIB184 but not in those from IBSC07/pIB184 (data not shown). To identify this band, we excised it from the gel and analyzed it by mass spectrometry as described previously (6). About 15 peptides were identified by mass spectrometry analysis, and all corresponded to the SMU.1342 gene product, which is encoded by TnSmu2. The apparent molecular weight of this band also correlated well with the predicted mass of SMU.1342 (313 kDa). To confirm that the absence of this band was due to SMU.1349 inactivation, total cellular protein was also analyzed in IBSC07 carrying pIBC55, a plasmid containing full-length SMU.1349 under the control of the P23 promoter in plasmid pIB184 (5). The missing band reappeared in the complemented strain, suggesting that the loss of the SMU.1342 gene product in the crude lysate of IBSC07 was due to the deletion of SMU.1349.

Fig. 1.

Protein profile of the S. mutans wild-type strain (UA159/pIB184), the SMU.1349 mutant strain (IBSC07/pIB184), and the complemented strain (IBSC07/pIBC55). Whole-cell lysates were prepared from strains grown overnight in THY medium. Equal amounts of protein were resolved in a 4 to 20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel and were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue stain. The band, indicated by the arrow, was excised and identified by mass spectrometry as described previously (6). M, prestained molecular weight marker (Fermentas).

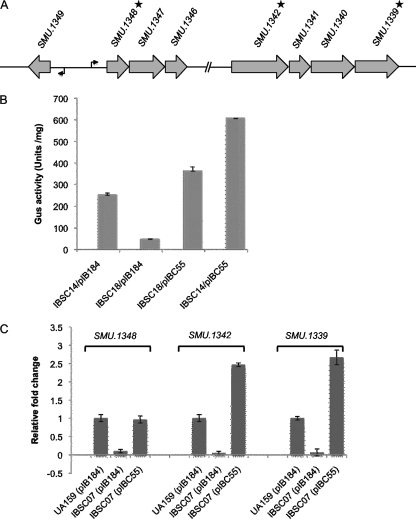

Since SMU.1349 encodes a TetR family regulator, and since these regulators can act as activators, we asked whether SMU.1349 activates expression at the transcriptional level. SMU.1342 is a part of a large operon within the TnSmu2 locus. The putative start site of the operon is in the intergenic region between SMU.1349 and SMU.1348; these two genes are transcribed divergently (Fig. 2A). To determine whether SMU.1349 can activate the promoter of this operon, we used a transcriptional reporter fusion for analysis to avoid any cis effect that may alter gene expression. Transcriptional reporter fusion strains were constructed by cloning the putative promoter region located in front of SMU.1348 into plasmid pIB107, which contains a promoterless gusA gene (6). This construct was inserted at the SMU.1405 locus, which is well separated from the TnSmu2 locus. The wild-type strain carrying the empty vector (IBSC14/pIB184), the SMU.1349 deletion mutant with the empty vector (IBSC18/pIB184), and the complemented deletion mutant strain (IBSC18/pIBC55), all containing the PSMU.1348-gusA transcriptional fusion reporter, were assayed for GUS activity. As shown in Fig. 2B, GusA activity was significantly reduced in the mutant strain IBSC18, indicating that SMU.1349 is required to activate transcription from PSMU.1348. However, GusA activity was restored to slightly more than the parental level when the ΔSMU.1349 strain was complemented with SMU.1349 in trans (IBSC18/pIBC55). Furthermore, when we tested the wild-type strain containing the complementing plasmid pIBC55, GUS activity increased to nearly 2-fold. Taken together, the results of the reporter fusion assays indicate that SMU.1349 induces SMU.1348 promoter expression.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of transcription by SMU.1349 at the TnSmu2 locus. (A) Schematic representation of the TnSmu2 locus. Open reading frames are represented by shaded arrows, and the orientation indicates the direction of transcription. Bent arrows indicate the putative transcription start site, and asterisks indicate the genes used for qRT-PCR analysis. (B) Glucuronidase assay results demonstrating the effect of SMU.1349 mutation on the PSMU.1348 promoter. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR assay indicating the effects of SMU.1349 mutation on the expression of the SMU.1348, SMU.1342, and SMU.1339 genes in the TnSmu2 locus. The results are representative of two to three independent experiments each. The expression of genes was normalized to 1 in the wild-type strain with respect to gyrA expression. See the text for details.

To confirm the effect of SMU.1349 on the transcription of other genes in the TnSmu2 locus, we performed real time RT-PCR analyses using RNA extracted from UA159/pIB184, IBSC07/pIB184, and IBSC07/pIBC55 at the mid-exponential growth phase. Gene-specific primers corresponding to the SMU.1339, SMU.1342, and SMU.1348 genes were used to measure the levels of the transcripts produced from each of the three strains. The gyrA gene was included as a control to ensure that equivalent amounts of RNA were being used for each reaction. Figure 2C shows that higher levels of the SMU.1348 transcript were produced from the wild-type strain than from the mutant strain (IBSC07), with an approximately 10-fold difference in expression. Complementation of the ΔSMU.1349 mutant strain with plasmid pIBC55 (IBSC07/pIBC55), which carries the full-length SMU.1349 gene in trans, restored SMU.1348 expression to the wild-type level. Similarly, low levels of both the SMU.1339 and SMU.1342 transcripts—about one-tenth of the levels in the wild-type strain—were produced by the ΔSMU.1349 mutant. Surprisingly, the complemented strain (IBSC07/pIBC55) produced levels of transcripts twice as high as those in the wild-type strain. Thus, taken together, our results suggest that SMU.1349 activates the expression of the entire NPRS-PKS operon in the TnSmu2 locus either directly or indirectly.

Direct binding of SMU.1349 to the PSMU.1348 promoter.

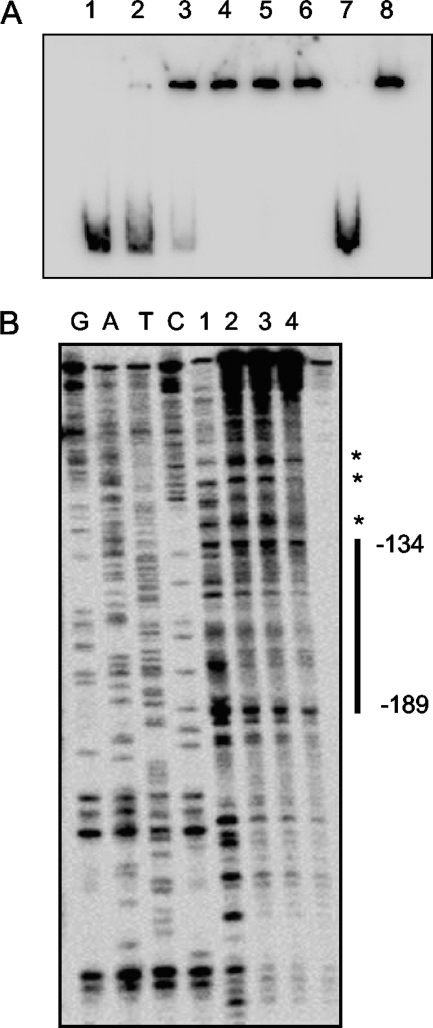

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and DNase I protection assays were used to demonstrate the specific binding of purified His-SMU.1349 protein to the putative promoter region of SMU.1348, PSMU.1348. As shown in Fig. 3A, incubation of a 275-bp DNA fragment, corresponding to positions +27 to −248 (with respect to the translation start site), with increasing amounts of SMU.1349 protein led to retardation of the mobility of the DNA fragment. Incubation of the 32P-labeled PSMU.1348 fragment with a 20-fold-larger amount of the nonlabeled PSMU.1348 DNA fragment resulted in no shifting of the labeled band (Fig. 3A, lane 7), while the addition of a 20-fold-larger amount of a DNA fragment containing the promoter region for the nlmA gene (PnlmA), which encodes a peptide component of mutacin IV and is not regulated by SMU.1349, did not inhibit shifting of the SMU.1349-bound PSMU.1348 fragment (Fig. 3A, lane 8). This demonstrates that SMU.1349 binds specifically to the promoter region of SMU.1348.

Fig. 3.

Interaction of the SMU.1349 protein at the SMU.1348 promoter region. (A) A gel shift assay was performed using 1 pmol of a DNA fragment containing the putative SMU.1348 promoter region (∼275 bp), incubated with increasing amounts of His-tagged SMU.1349. Lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 28 pmol; lane 3, 56 pmol; lane 4, 84 pmol; lane 5, 112 pmol; lane 6, 140 pmol; lane 7, specific competition using 112 pmol protein and 20 pmol of cold PSMU.1348; lane 8, nonspecific competition using 112 pmol protein and 20 pmol of cold PnlmA (212 bp). (B) DNase I protection assay demonstrating the interaction of the SMU.1349 protein at the SMU.1348 promoter region. The position of the protected region is indicated with reference to the translation start site of SMU.1348. Asterisks indicate DNase I-hypersensitive sites. The results are representative of two independent experiments. See the text for details.

DNase I protection assays were performed, using the same PSMU.1348-SMU.1349 complexes prepared for EMSA, as described above, to determine the portion of PSMU.1348 that binds to SMU.1349. Analysis of the gel indicated that SMU.1349 binds to the DNA fragment from position −189 to −134 relative to the start codon of SMU.1348 and protects this region from digestion by DNase I (Fig. 3B). Taken together, the results of the EMSA and DNase I analyses suggest that SMU.1349 activates the expression of SMU.1348 and other genes by binding specifically to the promoter region upstream of the SMU.1348 gene.

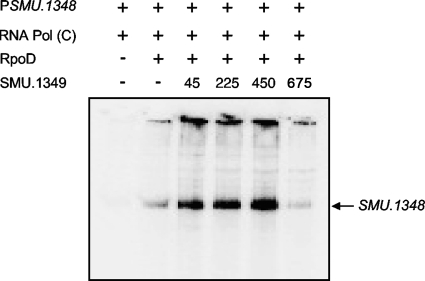

SMU.1349 can activate gene transcription in vitro.

In vitro transcription assays were performed to demonstrate direct activation of expression from PSMU.1348. A linear DNA fragment, containing the first 27 bp of SMU.1348 as well as the putative promoter elements, was PCR amplified from the pIBC58 plasmid and was used as a template for the in vitro transcription runoff assays. To perform the reaction, the E. coli RNA polymerase core enzyme was reconstituted with purified His-tagged RpoD from S. mutans. As shown in Fig. 4, the addition of reconstituted RNA polymerase, but not the core enzyme only, generated bands of the expected size, 250 nucleotides (nt), when PSMU.1348 was used as a template (Fig. 4, first and second lanes). The addition of increasing amounts of purified SMU.1349 to the in vitro reaction mixture led to increases in transcription from PSMU.1348. However, the addition of saturating amounts of SMU.1349 ultimately blocked overall transcription from the PSMU.1348 promoter. Thus, it appears that SMU.1349 can activate transcription from the PSMU.1348 promoter in vitro without the need for any accessory factors.

Fig. 4.

In vitro transcription runoff assay done using the putative promoter region of SMU.1348 (200 ng) in the presence of increasing amounts of SMU.1349 protein (45 to 675 pmol) with E. coli core RNA polymerase (Epicentre) and purified S. mutans sigma factor (RpoD). Transcription products were resolved on an 8% denaturing urea gel. This gel is representative of two independent experiments.

SMU.1349 also acts as a repressor.

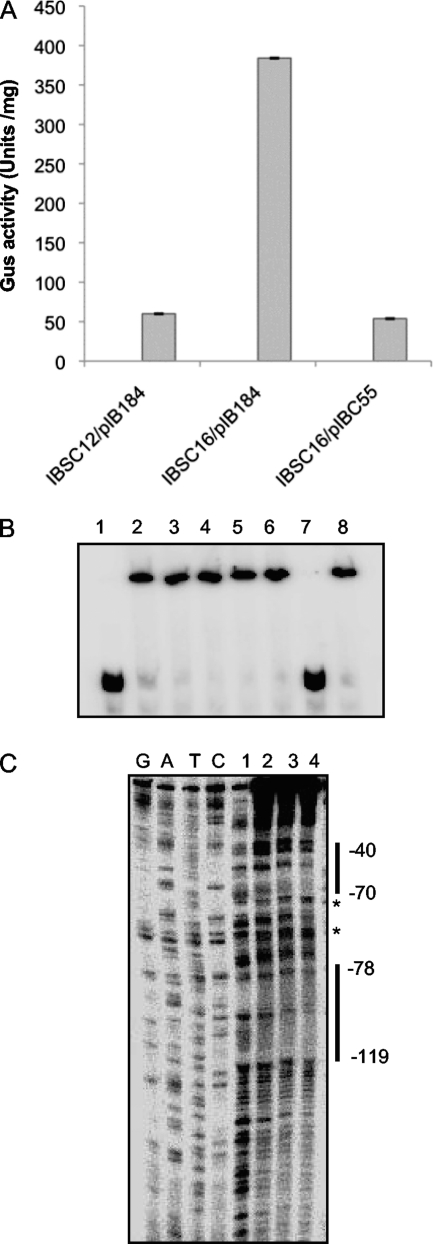

SMU.1349 and SMU.1348 are transcribed divergently (Fig. 2A), and the length of the intergenic region between these two genes is 352 bp. Since SMU.1349 binds to the promoter region of SMU.1348, we asked whether SMU.1349 could also regulate its own expression. We first tested the expression of PSMU.1349 by generating a PSMU.1349-gusA reporter fusion as described in Materials and Methods. Strain IBSC12 contains a PSMU.1349-gusA transcriptional fusion in the chromosome. As before, SMU.1349 was inactivated by allelic exchange to create IBSC16. The transcription of PSMU.1349 was quantitated in these strains (containing an empty vector) by measuring the GusA activity produced from the PSMU.1349-gusA reporter fusion (Fig. 5A). We also found that deletion of SMU.1349 increased PSMU.1349 expression. The difference was about 8-fold and was significant (P, ≤0.05). In order to confirm that increased PSMU.1349 expression was indeed caused by the ΔSMU.1349 mutation, IBSC16 was complemented with pIBC55. As expected, the level of PSMU.1349 expression produced by IBSC16/pIBC55 was similar to that produced by the wild-type strain containing an empty vector (IBSC12/pIB184). Thus, unlike SMU.1348 expression, SMU.1349 expression is repressed by SMU.1349 at the transcriptional level.

Fig. 5.

Interaction of SMU.1349 at its own promoter. (A) A GUS assay indicates that SMU.1349 acts as a repressor of its own expression. (B) SMU.1349 interacts directly at its own promoter, as indicated by a gel shift assay. EMSA was performed using 1 pmol of a DNA fragment containing the putative promoter region of SMU.1349 (189 bp), incubated with increasing amounts of His-tagged SMU.1349 protein. Lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 28 pmol; lane 3, 56 pmol; lane 4, 84 pmol; lane 5, 112 pmol; lane 6, 140 pmol; lane 7, specific competition using 112 pmol protein and 20 pmol of cold PSMU.1349; lane 8: nonspecific competition using 112 pmol protein and 20 pmol of cold PnlmA (212 bp). (C) DNase I protection assay demonstrating the interaction of SMU.1349 protein at the SMU.1349 promoter region. The positions of the protected regions are indicated with reference to the translation start site of SMU.1349. Asterisks indicate DNase I-hypersensitive sites. The results are representative of two independent experiments. See the text for details.

To determine whether this regulation is direct, we studied the binding of SMU.1349 to the PSMU.1349 promoter. We made a PCR product of 189 bp corresponding to positions +1 to −188 with respect to the translation start site and used it in a DNA-binding assay. As shown in Fig. 5B, His-tagged SMU.1349 bound increasingly to the PSMU.1349 promoter DNA fragment as the amount of protein increased. The addition of a 20-fold molar excess of the unlabeled PnlmA fragment had no effect on binding. Taken together, our results suggest that SMU.1349 specifically binds to PSMU.1349.

DNase I footprinting assays were then performed to localize the DNA-binding sites of SMU.1349 on the PSMU.1349 promoter. We used the same 189-bp fragment that was used in the gel shift assay. We found two DNase I protection regions on PSMU.1349 that span positions −40 to −70 and −78 to −119 with respect to the translation start site (Fig. 5C). In addition, we also observed hypersensitive sites, suggesting that the binding of SMU.1349 to the DNA may cause DNA bending. Thus, our results show that SMU.1349 represses its own expression by binding directly to the promoter.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized a transcriptional regulator from S. mutans, SMU.1349, that belongs to the TetR family proteins. The operon that encodes this regulator is part of a genomic island acquired by the organism via horizontal gene transfer. Recently, it was shown that the operon contains a gene cluster that encodes a hybrid PKS-NRPS metabolite, mutanobactin A, which is capable of inducing the hypha-to-yeast transition of Candida albicans, an opportunistic human pathogen often present in the oropharyngeal cavity (18).

SMU.1349 bound to three distinct regions on the intergenic sequence, as evident from the DNase I protection assay. By aligning these three regions, we obtained a 16-bp sequence, TA(T/A)T(G/C)T(T/A)T(T/A)(T/A)T(A/G)(A/T)T(T/A)A, that may serve as a potential SMU.1349 operator. However, this 16-bp sequence does not display the characteristics of TetR operator sites. TetR family regulators generally bind as dimers to operator sequences containing dyad symmetry, and the exact sequences differ depending on the specific protein. For example, E. coli TetR binds a 15-bp operator with 7-bp dyad symmetry and only a 1-base spacer. However, S. aureus QacR, which controls the expression of quaA, encoding a multidrug efflux pump, binds to an unusually long operator site consisting of a 28-bp sequence with 14-bp dyad symmetry. While the dyad symmetry in the operator sequence is very prominent for both TetR and QacR, the dyad symmetry in the operators for many other TetR family proteins is not so apparent. Examples include the LuxR protein of Vibrio harveyi, which binds to a 21-bp operator with imperfect dyad symmetry (31). The operator sequence for LuxR was determined by using a protein binding microarray (PBM) containing about 40,000 double-stranded DNA sequences with all possible 10-mer variants and various spacer lengths. Thus, whether the 16-bp sequence that we identified is the authentic SMU.1349 operator sequence remains to be determined.

There are at least two different mechanisms by which TetR family regulators function as repressors. In the case of E. coli TetR, the operator sequences overlap with the promoters for tetA and tetR, thereby blocking the access of RNA polymerase to the promoter sequence (27). On the other hand, the QacR protein represses the transcription of the quaA gene by hindering the RNA polymerase-promoter complex from entering into a productive transcribing state rather than by blocking RNA polymerase binding (11). We found that SMU.1349 acts as a repressor and suppresses its own expression. SMU.1349 was bound to two distinct regions upstream of the SMU.1349 ORF. The first region corresponded to positions −40 to −70, while the second region corresponded to positions −78 to −119 (both numbered with respect to the first codon). Thus, it is most likely that the binding of SMU.1349 to its own promoter blocks RNA polymerase from accessing the promoter.

As mentioned above, a few TetR family regulators also function as activators. However, the exact mechanisms by which these unorthodox regulators activate gene expression are not well understood, except for Streptococcus pneumoniae SczA, a metal ion-dependent transcriptional activator required for the Zn2+ resistance of this organism (19). SczA activates the expression of the Zn2+ resistance gene czcD by binding in a Zn2+-dependent manner to the cdcZ promoter at a conserved site, which is just upstream of the transcription start site. This binding facilitates the recruitment of RNA polymerase to the promoter. In the absence of Zn2+, SczA binds to a second site that maps downstream of the promoter and blocks RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter (19). Our in vivo and in vitro transcription data clearly indicate that SMU.1349 functions as a transcriptional activator. It does so by directly binding to the promoter of the TnSMu2 operon. The binding site for SMU.1349 mapped just upstream of the corresponding promoter (Fig. 3). Thus, we speculate that SMU.1349 functions as either a class I or a class II type activator and not as an antirepressor.

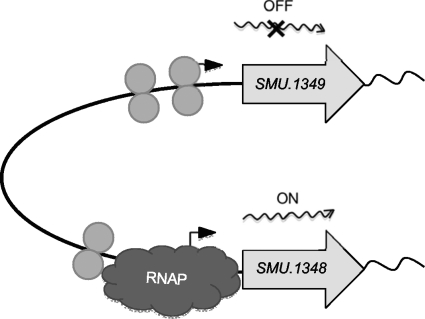

Although our in vitro transcription assay suggests that SMU.1349 can activate transcription without any accessory factors, it is possible that in vivo, transcription may be further augmented by the presence of additional ligands, since most of the TetR family proteins bind to a ligand for modulation of transcription. Analysis of the primary sequence suggests that the C-terminal region of SMU.1349 is very different from those of the rest of the S. mutans TetR family proteins (data not shown). A BLAST search with the last 100 residues identified only a TetR family protein from Streptococcus sanguinis that shows >65% similarity (data not shown). Since the C-terminal region is the place where the ligand binds to modulate the DNA binding activity of the protein (32), it is possible that both these regulators may bind to a common ligand that may be present either in the saliva or in the dental plaque. Furthermore, the operon activated by SMU.1349 is responsible for the synthesis of mutanobactin A, a cyclic tetrapeptide. It is possible that in vivo, either mutanobactin A or any of the intermediate biosynthesis products may bind to SMU.1349 to modulate its activity. Based on our in vivo and in vitro results, we propose a model for SMU.1349-mediated gene expression (Fig. 6). We believe that the binding of SMU.1349 to the intergenic region causes DNA bending, since we have observed many DNase I-hypersensitive sites at the intergenic region upon SMU.1349 binding (Fig. 3 and 5). This binding may further facilitate the interaction of RNA polymerase with the TnSmu2 promoter and the activation of transcription.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the possible model of transcription regulation by the SMU.1349 protein at the SMU.1349–SMU.1348 intergenic region. Binding of the monomeric or oligomeric forms of the regulator causes localized bending of the SMU.1349 promoter, leading to transcription repression, whereas the regulator recruits the RNA polymerase (RNAP) to the SMU.1348 promoter region, initiating transcription at this locus. The bent arrows indicate the putative transcription start site.

The regulation of the TnSMu2 operon appears to be highly complex. In our earlier study, we observed that ClpP, a major intracellular protease, is required for the expression of the TnSmu2 operon (7). In a ClpP-deficient strain, the expression of this operon was decreased about 5-fold, and the expression of the SMU.1349 gene was increased about 2-fold (7). Although the exact mechanism by which ClpP affects TnSmu2 expression is currently unknown, we speculate that in the absence of ClpP, SMU.1349 may become unstable. Although ClpP is known to degrade many transcriptional regulators, we believe that ClpP does not degrade SMU.1349 directly. Rather, an unknown protease, whose expression is induced when ClpP is absent, may degrade SMU.1349, thereby affecting the expression of TnSmu2. Alternatively, proper folding of the SMU.1349 protein may require a chaperone whose function is dependent on ClpP. The expression of the TnSmu2 operon is also dependent on CovR, a response regulator that appears to regulate as much as ∼6.5% of the genome (10). CovR seems to induce the expression of TnSmu2, but the activation is indirect, since the addition of purified CovR in an in vitro transcription assay did not stimulate TnSmu2 transcription (data not shown). Thus, understanding of the regulation of TnSmu2 expression requires further molecular investigations, some of which are currently being conducted in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was made possible by an NIDCR grant (DE016686) to I.B.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 30 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aravind L., Anantharaman V., Balaji S., Babu M. M., Iyer L. M. 2005. The many faces of the helix-turn-helix domain: transcription regulation and beyond. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:231–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banerjee A., Biswas I. 2008. Markerless multiple-gene-deletion system for Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2037–2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bateman A., et al. 2002. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:276–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biswas I., Drake L., Biswas S. 2007. Regulation of gbpC expression in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 189:6521–6531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biswas I., Jha J. K., Fromm N. 2008. Shuttle expression plasmids for genetic studies in Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 154:2275–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biswas S., Biswas I. 2006. Regulation of the glucosyltransferase (gtfBC) operon by CovR in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:988–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chattoraj P., Banerjee A., Biswas S., Biswas I. 2010. ClpP of Streptococcus mutans differentially regulates expression of genomic islands, mutacin production, and antibiotic tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 192:1312–1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chong P., Chattoraj P., Biswas I. 2010. Activation of the SMU.1882 transcription by CovR in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 5:e15528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christen S., et al. 2006. Regulation of the Dha operon of Lactococcus lactis: a deviation from the rule followed by the TetR family of transcription regulators. J. Biol. Chem. 281:23129–23137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dmitriev A., et al. 2011. CovR-controlled global regulation of gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 6:e20127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grkovic S., Brown M. H., Roberts N. J., Paulsen I. T., Skurray R. A. 1998. QacR is a repressor protein that regulates expression of the Staphylococcus aureus multidrug efflux pump QacA. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18665–18673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hamada S., Slade H. D. 1980. Biology, immunology, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Rev. 44:331–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hillen W., Klock G., Kaffenberger I., Wray L. V., Reznikoff W. S. 1982. Purification of the TET repressor and TET operator from the transposon Tn10 and characterization of their interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 257:6605–6613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hillerich B., Westpheling J. 2008. A new TetR family transcriptional regulator required for morphogenesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 190:61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hinrichs W., et al. 1994. Structure of the Tet repressor-tetracycline complex and regulation of antibiotic resistance. Science 264:418–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horaud T., Delbos F. 1984. Viridans streptococci in infective endocarditis: species distribution and susceptibility to antibiotics. Eur. Heart J. 5(Suppl. C):39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ishihama A. 2010. Prokaryotic genome regulation: multifactor promoters, multitarget regulators and hierarchic networks. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:628–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joyner P. M., et al. 2010. Mutanobactin A from the human oral pathogen Streptococcus mutans is a cross-kingdom regulator of the yeast-mycelium transition. Org Biomol. Chem. 8:5486–5489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kloosterman T. G., van der Kooi-Pol M. M., Bijlsma J. J., Kuipers O. P. 2007. The novel transcriptional regulator SczA mediates protection against Zn2+ stress by activation of the Zn2+-resistance gene czcD in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1049–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lemos J. A., Abranches J., Burne R. A. 2005. Responses of cariogenic streptococci to environmental stresses. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 7:95–107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levy S. B., et al. 1989. Nomenclature for tetracycline resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:1373–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loesche W. J. 1986. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 50:353–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maruyama F., et al. 2009. Comparative genomic analyses of Streptococcus mutans provide insights into chromosomal shuffling and species-specific content. BMC Genomics 10:358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McIver K. S. 2009. Stand-alone response regulators controlling global virulence networks in Streptococcus pyogenes. Contrib. Microbiol. 16:103–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murray D. S., Schumacher M. A., Brennan R. G. 2004. Crystal structures of QacR-diamidine complexes reveal additional multidrug-binding modes and a novel mechanism of drug charge neutralization. J. Biol. Chem. 279:14365–14371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nickel J., Irzik K., van Ooyen J., Eggeling L. 2010. The TetR-type transcriptional regulator FasR of Corynebacterium glutamicum controls genes of lipid synthesis during growth on acetate. Mol. Microbiol. 78:253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Orth P., Schnappinger D., Hillen W., Saenger W., Hinrichs W. 2000. Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet repressor-operator system. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pareja E., et al. 2006. ExtraTrain: a database of extragenic regions and transcriptional information in prokaryotic organisms. BMC Microbiol. 6:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perez-Casal J., Caparon M. G., Scott J. R. 1992. Introduction of the emm6 gene into an emm-deleted strain of Streptococcus pyogenes restores its ability to resist phagocytosis. Res. Microbiol. 143:549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pfaffl M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pompeani A. J., et al. 2008. The Vibrio harveyi master quorum-sensing regulator, LuxR, a TetR-type protein is both an activator and a repressor: DNA recognition and binding specificity at target promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 70:76–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramos J. L., et al. 2005. The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:326–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Siebold C., Garcia-Alles L. F., Erni B., Baumann U. 2003. A mechanism of covalent substrate binding in the X-ray structure of subunit K of the Escherichia coli dihydroxyacetone kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:8188–8192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Waterhouse J. C., Russell R. R. 2006. Dispensable genes and foreign DNA in Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 152:1777–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Waters C. M., Bassler B. L. 2006. The Vibrio harveyi quorum-sensing system uses shared regulatory components to discriminate between multiple autoinducers. Genes Dev. 20:2754–2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu C., et al. 2010. Genomic island TnSmu2 of Streptococcus mutans harbors a nonribosomal peptide synthetase-polyketide synthase gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of pigments involved in oxygen and H2O2 tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:5815–5826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.