Abstract

As a result of a frameshift mutation, the hsdS locus of the NgoAV type IC restriction and modification (RM) system comprises two genes, hsdSNgoAV1 and hsdSNgoAV2. The specificity subunit, HsdSNgoAV, the product of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene, is a naturally truncated form of an archetypal specificity subunit (208 N-terminal amino acids instead of 410). The presence of a homonucleotide tract of seven guanines (poly[G]) at the 3′ end of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene makes the NgoAV system a strong candidate for phase variation, i.e., stochastic addition or reduction in the guanine number. We have constructed mutants with 6 guanines instead of 7 and demonstrated that the deletion of a single nucleotide within the 3′ end of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene restored the fusion between the hsdSNgoAV1 and hsdSNgoAV2 genes. We have demonstrated that such a contraction of the homonucleotide tract may occur in vivo: in a Neisseria gonorrhoeae population, a minor subpopulation of cells appeared to have only 6 guanines at the 3′ end of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene. Escherichia coli cells carrying the fused gene and expressing the NgoAVΔ RM system were able to restrict λ phage at a level comparable to that for the wild-type NgoAV system. NgoAV recognizes the quasipalindromic interrupted sequence 5′-GCA(N8)TGC-3′ and methylates both strands. NgoAVΔ recognizes DNA sequences 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′ and 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′, although the latter sequence is methylated only on the complementary strand within the 5′-CTCA-3′ region of the second recognition target sequence.

INTRODUCTION

Restriction and modification (RM) systems are composed of two enzymatic activities that recognize the same specific DNA sequence. The restriction endonuclease cleaves the DNA, unless the recognized sequence is methylated by the modification methylase. RM systems are found in a wide variety of bacteria and archaea, and their main role is to protect cells from bacteriophage infections or the uptake of undesirable foreign DNA (7, 33). The importance of RM systems in host protection is difficult to estimate in the case of bacteria for which no phages or no phage detection methods are known and that encode several RM systems, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae (43, 34). Recently, a new role for RM systems as factors regulating other gene expression was proposed for type III RM systems (16, 42).

Type I DNA RM systems are multimeric enzyme complexes that recognize and methylate an adenine residue within a specific DNA sequence. The cleavage of double-stranded DNA takes place at an undefined region, several hundreds to thousands of base pairs away from the recognized sequence. The archetypal type I methyltransferases are encoded by two genes, hsdS and hsdM, and are composed of one HsdS subunit and two HsdM subunits. The HsdS subunit is responsible for recognition and binding of DNA by the enzymatic complex and for the interaction of the other subunits of the enzyme. The product of the hsdR gene is necessary for endonucleolytic activity. The latest issue of REBASE (http://rebase.neb.com/rebase) contains several hundred type I RM systems recognizing tens of unique recognition sequences (37). Sequences recognized by type I RM systems have the same general organization: 3 specific nucleotides separated from another 3 or 4 specific nucleotides by a nonspecific 6- to 8-nucleotide spacer. For example, the archetypal type IC RM system enzyme Eco124II recognizes the bipartite sequence 5′-GAA(N7)RTCG-3′ (R, purine [A or G]) (36). The nature of this recognition sequence reflects the circular organization of the HsdS polypeptide (27). An archetypal HsdS subunit is composed of two variable target recognition domains (TRDs) that are separated by a central domain, conserved among family members. TRDs are flanked by conserved amino- and carboxy-terminal domains which vary in length within the family. The central domain acts as a spacer between the two variable domains and thus determines the length of the nonspecific spacer in the recognized target sequence (2, 18, 19, 35). Detailed studies have shown that the conserved domain (CD) may be divided into subdomains, which are duplicated at the N or C terminus (Fig. 1, panel 2a) (27). Subdomain A is responsible for the interaction with HsdM. Subdomain B determines the spacer length in the recognized DNA sequence (18, 33) and is considered to form an “elbow” that joins two arms and gives the structure some flexibility. Subdomain D is a split repeat duplicated only at the N-terminal end.

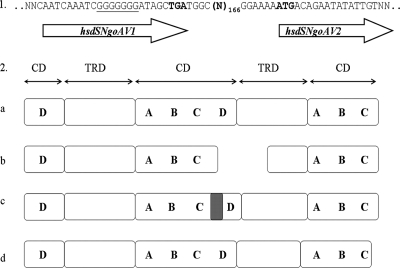

Fig. 1.

(1) Genetic organization of the wild-type hsdSNgoAV locus (34). The stop codon (TGA) and ATG sequences are in boldface, and N represents nucleotides. Arrows represent the interrupted hsdSNgoAV1 and hsdSNgoAV2 genes. The poly(G) tract is underlined, and the deleted thymine is located within the TGA stop codon. (2) Domain organization of type IC HsdS subunits and mutants. The organization of the archetypal HsdSEcoR124I/DXXI polypeptide (408 aa) (a), wild-type HsdS1NgoAV polypeptide (208 aa) and potential HsdS2NgoAV (138 aa) (b), mutant HsdSNgoAVΔT or HsdSNgoAVΔG (406-aa) polypeptides (c), and mutant HsdSNgoAVΔ40 (393-aa) polypeptide (d) is shown. The polypeptides encoded by hsdS genes may be divided into two variable DNA-binding domains (also called target recognition domains [TRDs]) and three conserved domains (CDs). Within conserved regions of the IC RM family members, duplicated subdomains A, B, C, and D are defined (27). The gray bar represents the additional 13 amino acids present in HsdSNgoAVΔT/G mutant subunits, compared to HsdSEcoR124I or HsdSEcoDXXI. This region is deleted in the HsdSNgoAVΔ40 polypeptide.

It has been proposed that the hsdS locus was formed by a gene duplication event (5). This hypothesis is supported by the fact that artificially truncated HsdS forms, composed only of the N- or C-terminal half of the native polypeptide, can function as a recognition subunit and recognize a quasipalindromic target sequence (1, 19, 31). For example, the methyltransferase EcoDXXI recognizes the sequence 5′-TCA(N7)RTTC-3′ (29). The expression of a truncated hsdSEcoDXXI gene, encoding only the N-terminal TRD and the central CD, generated an enzyme that recognized the interrupted palindrome 5′-TCA(N8)TGA-3′. When only the C-terminal TRD and the central CD were expressed, the mutant enzyme recognized the sequence 5′-GAAY(N5)RTTC-3′ (29, 31).

Previously, we described the first active, naturally truncated form of the HsdS subunit, which forms part of the NgoAV RM system of N. gonorrhoeae (34). This type IC RM system is encoded by four genes: hsdMNgoAV, hsdRNgoAV, hsdSNgoAV1, and hsdSNgoAV2 (Fig. 1, panel 1). The interrupted hsdS locus is probably due to a frameshift mutation and the formation of a stop codon (Fig. 1, panel 1). We demonstrated that the product of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene, HsdSNgoAV, is responsible for the specificity of NgoAV for the interrupted palindromic sequence 5′-GCA(N8)TGC-3′. The organization of HsdSNgoAV (208 amino acids [aa]) is similar to the structure of truncated HsdS proteins of the EcoDXXI and EcoR124II RM systems obtained by in vitro and in vivo manipulations (1, 2, 31). Moreover, the conserved regions of NgoAV comprise the same subdomains as those in EcoR124II (Fig. 1, panels 2a and 2b). The presence or absence of the hsdSNgoAV2 gene does not affect NgoAV specificity (34). The polypeptide encoded by hsdSNgoAV2 is nonfunctional, probably because it lacks a central CD and has a truncated TRD (Fig. 1, panel 2b).

In this study, we show that reversion of the frameshift mutation in the hsdS locus of the N. gonorrhoeae NgoAV RM system by deletion of 1 nucleotide upstream of the stop codon results in the restitution of the long form of the locus, called hsdSNgoAVΔ. Analysis of other mutants with restored fusion between hsdSNgoAV1 and hsdSNgoAV2 indicates the important role of a 13-amino-acid motif in the central CD, between regions C and D. This motif is present only in the HsdSNgoAVΔ polypeptide; it is absent in archetypal type IC HsdS subunits. The newly formed HsdSNgoAVΔ subunit recognizes a new specific DNA sequence, and the resulting restriction enzyme is active and able to restrict unprotected λ bacteriophage in vivo. We also demonstrate that the restitution of HsdSNgoAVΔ occurs in vivo by deletion of one guanine from the homopolymeric poly(G) tract within the 3′ end of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene. The role of such deletions and their correlation with phase variation (PV) and pathogenesis of Neisseria spp. are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, phages, plasmids, and growth media.

The Escherichia coli strain Top10 [mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80 Δlac ΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK λ rpsL endA1 mupG] (Invitrogen) and its derivatives were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (39). Antibiotics were included in the medium at the following final concentrations: 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 10 μg/ml tetracycline. N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 (ATCC 700825) was grown on GC medium base (GCB; Difco) plus Kellogg supplements (26) at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Enzymes and chemicals.

Restriction enzymes, long PCR enzyme mix, Pfu polymerase, and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Fermentas. PfuUltra high-fidelity DNA polymerase was purchased from Stratagene. Other chemicals were reagent grade or better and were obtained from Sigma, unless stated otherwise. All oligonucleotides were purchased from IBB (Poland).

Construction of plasmids carrying fused hsdSNgoAV1 and hsdSNgoAV2 sequences of the NgoAV RM system.

All routine DNA manipulations were carried out according to standard protocols (39). Plasmid pMS2, carrying hsdMNgoAV, dinD, hsdSNgoAV1, and hsdSNgoAV2, was used as the template for mutagenesis (34). Plasmids pMS2ΔT and pMS2Δ40 were constructed by long PCR using appropriate primers (containing the site-directed mutations) annealing either side of the deleted sequences (inside-out). Plasmid pMS2ΔG, with 6 guanines instead of 7, was constructed after site-directed mutagenesis by cloning a 631-bp BseJI/NcoI fragment, produced by restriction of a 3.5-kb PCR product, into the BseJI/NcoI sites of plasmid pMS2. All primers used for mutagenesis are listed in Table SA in the supplemental material. The DNA sequences of all new constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

The 4,383-bp EheI fragment from pMS2ΔT carrying hsdM and hsdSNgoAVΔT was ligated with the DNA fragment (5,794 bp) encoding HsdRNgoAV, which was excised with EheI from pNo12 (plasmid pUC19 carrying the wild-type NgoAV RM system [3]). The resulting construct, pNo12ΔT, was digested with BamHI and HindIII, and the 7,521-bp DNA fragment encoding the modified RM system was ligated into the BamHI/HindIII sites of pACYC184, resulting in the low-copy-number plasmid pSMRX. This construct is compatible with all vectors containing the pMB1 replicon (39). The plasmids constructed and used in this study are listed in Table SB in the supplemental material.

In vivo restriction-modification activity assay.

The E. coli Top10 strain, containing the appropriate plasmids (see Table 1), was used for bacteriophage λvir in vivo restriction and modification assays as described previously (3). Plasmid pR carries the hsdRNgoAV gene and is a pMPMT6Ω vector derivative which is compatible with all pUC19-derived plasmids (3).

Table 1.

Restriction and modification properties of the NgoAV system derivatives

| Plasmid(s) | EOPa of indicated form of λvirb |

Relevant phenotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ0 | λNgoAV | λNgoAVΔT | λNgoAVΔ40 | λNgoAVΔG | ||

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | r− m− |

| pNo12 | (2.0 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | (1.2 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | (6.0 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | (1.7 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | r+ mNgoAV+ |

| pMS2 + pR | (2.1 ± 0.2) × 10−4 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | NDc | ND | ND | r+ mNgoAV+ |

| pMS2ΔT + pR | (4.0 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | (2.1 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | ND | 1.1 ± 0.3 | r+ mNgoAVΔ+ (new specificity) |

| pMS2ΔG + pR | (1.4 ± 0.1) × 10−3 | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | 0.84 ± 0.5 | ND | ND | r+ mNgoAVΔ+ (new specificity) |

| pNo12ΔT | (3.0 ± 0.3) × 10−5 | (1.2 ± 0.7) × 10−5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | (1.2 ± 0.2) × 10−4 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | r+ mNgoAVΔ+ (new specificity) |

| pSMRX | (1.8 ± 0.8) × 10−4 | (4.6 ± 0.3) × 10−4 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | ND | ND | r+ mNgoAVΔ+ (new specificity) |

| pMS2Δ40 + pR | 0.62 ± 0.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | r− m− |

EOP, efficiency of plating. Values are PFU ml−1 formed on the indicator strain divided by PFU ml−1 formed on the propagating strain. Data are means of at least three independent experiments ± standard deviations.

λ0, unmodified bacteriophage propagated on the E. coli Top10 (r− m−) strain. Other phages were modified in vivo by propagation on E. coli Top10 cells expressing different RM systems.

ND, not determined.

Determination of the DNA sequence recognized by NgoAVΔ methyltransferase.

Plasmid DNAs with known sequences were isolated from E. coli Top10 cells expressing active NgoAVΔ methyltransferase (pNo12ΔT, pMS2ΔT, pMS2ΔG, or pSMRX) and digested with different restriction endonucleases described as being sensitive to adenine methylation by the manufacturer (Fermentas, New England BioLabs) and/or REBASE: AccI, BclI, BsaAI, BseGI, BseMI, CailI, Cfr10I, DraI, Eam1104I, Eco57I, EcoRI, EcoRV, Esp1396I, HincII, HindIII, HinfI, HphI, LweI, MnlI, MvaI, NruI, PaeI, PvuI, PvuII, SacI, SalI, SapI, ScaI, SspI, TaaI, TaiI, TaqI, VspI, XbaI, and XhoI. The resulting restriction fragments were resolved by electrophoresis in agarose or agarose-acrylamide gels (39), and the digestion patterns were compared with those predicted in silico (CLONE MANAGER 7; Scientific & Educational Software, Durham, NC). Relevant sequences are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Restriction patterns obtained after digestion of plasmid DNAs with specific restriction enzymes

| Position (nta) in plasmid DNA (plasmid) | Restriction enzyme (sequence recognized) | DNA sequence around site recognized by restriction enzyme (boldface)b |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction sites resistant to cleavage with restriction enzyme | ||

| 8989 (pNo12ΔΤ) | LweI (GCATC) | 5′-ATTGGTACAGGCATCGTGGTGTCACGCTGGTCG-3′ |

| 3′-TAACCATGTCCGTAGCACCACAGTGCGACCAGC-5′ | ||

| 784 (pNo12ΔΤ) | HincII (GTYRAC) | 5′-GCGTGCACGGGCAGGAGAAAGTCACAAAATCTA-3′ |

| 3′-CGCACGTGCCCGTCCTCTTTCAGTGTTTTAGAT-5′ | ||

| 1298 (pL4) | HinfI (GANTC) | 5′-CATTCTCCTGTGACTCGGAAGTGCATTTATCAT-3′ |

| 3′-GTAAGAGGACACTGAGCCTTCACGTAAATAGTA-5′ | ||

| Restriction site not resistant to cleavage with restriction enzyme | ||

| 6288 (pNo12ΔΤ) | LweI (GCATC) | 5′-GAGAAACGCCTGCATCAGGCCGTGATAGCGCAG-3′ |

| 3′-CTCTTTGCGGACGTAGTCCGGCACTATCGCGTC-5′ | ||

| Consensus protected sequence | 5′-GCANNNNNNNGTCA-3′ | |

| 3′-CGTNNNNNNNCAGT-5′ |

nt, nucleotide.

Matches to the consensus are underlined.

The double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) used to determine NgoAVΔ specificity were 35 to 39 bp long and had the sequence ACTGAATTCCGGXACACTGCAGTCT, where X represents the specific sequences listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Efficiency of methylation of double-stranded ODNs by NgoAVΔ, prepared from E. coli Top10(pSMRX) cells

| Duplex ODN sequencea | Methylationb (dpm) |

|---|---|

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N8)GTCAACACTGCAGTCT-3′c | 900 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N8)CAGTTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N8)GTCAACACTGCAGTCT-3′d | 1,600 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N8)CAGTTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N5)GTCACACTGCAGTCT-3′ | 3,100 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N5)CAGTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N8)GTCAACACTGCAGTCT-3′ | 3,140 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N8)CAGTTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGCTG(N7)ATAGCACTGCAGTCT-3′ | 3,200 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCGAC(N7)TATCGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N7)ATCAACACTGCAGTCT-3′ | 3,300 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N7)TAGTTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N7)GGCACACTGCAGTCT-3′ | 3,700 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N7)CCGTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N7)GTCACACTGCAGTCT-3′ | 33,200 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N7)CAGTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ | |

| 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCA(N7)CTCAACACTGCAGTCT-3′ | 78,300 |

| 3′-TGACTTAAGGCCCGT(N7)GAGTTGTGACGTCAGA-5′ |

Tested sequences are in boldface.

See Materials and Methods for details of the methylation assay.

No crude extract added.

Samples were heated for 20 min at 70°C before incubation at 37°C.

Crude cell extract preparation.

Cell pellets from 200-ml overnight cultures of E. coli Top10 containing pMS2ΔG or pSMRX and grown in LB medium supplemented with 0.5% l-arabinose were resuspended in 4 ml of buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, and 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The cells were disrupted by sonication, and cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Glycerol was added to the supernatants to a final concentration of 20%, and the cell extracts were stored frozen at −70°C prior to use.

Methyltransferase assays and radioactivity measurement.

Reaction mixtures containing 100 to 200 μg of total proteins and 1.7 pmol/μl substrate ODN duplex in a buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM EDTA, 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1.5 nM S-[methyl-3H]adenosylmethionine ([methyl-3H]AdoMet) (15 Ci/mmol; Perkin Life Sciences) were incubated at 37°C for 12 to 14 h. The reaction mixtures were then supplemented with 100 μl salmon sperm DNA (1 mg/ml) and spotted onto DE81 (Whatman) paper disks. These disks were washed with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and ethanol and dried, and bound radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation counter (Wallace, Pharmacia). In some experiments, the reaction mixtures were extracted with phenol and the aqueous phase was passed through a Sephadex G-100 column equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) buffer to separate the labeled DNA from low-molecular-mass radioactive material before counting. Alternatively, a nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen) was used for labeled ODN purification.

PV reporter vector construction and slipped-strand mispairing assay.

The lacZ′ gene, encoding the β-galactosidase α fragment, was amplified from E. coli K-12 genomic DNA using the primers shown in Table SA in the supplemental material. The 356-bp PCR product, digested with NcoI and HindIII, was cloned into the NcoI/HindIII sites of vector pMPMT4Ω (30) to place it under the control of the PBad promoter. The resulting construct, pMPMlacZ, was used as the PV reporter vector to confirm slipped-strand mispairing (SSM) within the poly(G) tract present in the hsdSNgoAV1 gene of N. gonorrhoeae.

Using appropriate primers (see Table SA in the supplemental material) and N. gonorrhoeae chromosomal DNA as the template, the region of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene between nucleotides 206 and 627 was amplified. The PCR product, containing ATG, the poly(G) tract, and the stop codon, was then digested with EcoRI and NcoI, and the 419-bp restriction fragment was cloned into the EcoRI/NcoI sites of pMPMlacZ upstream of the lacZ′ gene (Fig. 2). Whether or not the insertion of the amplified portion of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene formed a translational fusion with the lacZ′ gene depended on the number of guanines in the homopolymeric tract. Only in the case of translational fusion were blue colonies formed by E. coli Top10 carrying the construct after plating on LB agar supplemented with l-arabinose (0.5%) and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; 40 μg/ml), due to α-complementation between the fused gene and the chromosomal lacZΔM15 gene (45). To avoid PCR errors, PfuUltra high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Stratagene; error rate, 2.6 × 10−6) was used to amplify hsdSNgoAV1 fragments.

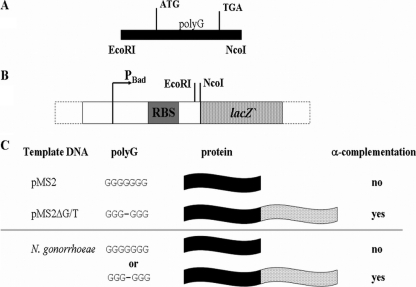

Fig. 2.

Detection of phase variation as a result of SSM at the hsdSNgoAV1 poly(G) sequence. (A) Fragment of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene containing the poly(G) tract amplified by PCR (with primers containing transcription start and stop signals). (B) Vector pMPMlacZ, containing the reporter gene lacZ′ (356-bp 5′ fragment from the E. coli K-12 lacZ gene) under the control of the PBad promoter to control expression of the fused protein (encoded by the amplified hsdSNgoAV1 fragments and lacZ′), able to complement the product of lacZΔM15 carried by E. coli Top10 cells. The PCR product was cloned as an EcoRI/NcoI fragment. RBS, ribosome binding site. (C) Depending on the number of guanines present in the poly(G) tract, a functional β-galactosidase is either expressed or not, and the color of the colonies on X-Gal-containing plates indicates the occurrence of SSM.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the completed Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA1090 genome is NG 002946.

RESULTS

Fusion of hsdSNgoAV1 and hsdSNgoAV2 genes from the NgoAV RM system of N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090.

The design of fused forms of HsdSNgoAV was made on the basis of comparisons between the in silico-translated sequences of the hsdSNgoAV1 and hsdSNgoAV2 genes and the sequences of the archetypal HsdSEcoR124I and HsdSEcoDXXI polypeptides (Fig. 1, panel 1). Particular care was taken to maintain the organization of the central conserved domain (Fig. 1, panel 2a). All mutants were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using the oligodeoxynucleotides listed in Table SA in the supplemental material. Plasmid pMS2ΔT, containing the wild-type hsdMNgoAV and mutated hsdSNgoAVΔT genes, was constructed by the deletion of one thymine within the stop codon (TGA) present at nucleotide position 625 of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene (Fig. 1, panel 1). Plasmid pMS2ΔG, containing wild-type hsdMNgoAV and mutated hsdSNgoAVΔG, was constructed by the deletion of one guanine present in the homopolymeric poly(G) tract (nucleotide positions 613 to 619) within the hsdSNgoAV1 gene. Both deletions resulted in reversion of the frameshift mutation and change in reading frame, so that translation could proceed through into the next open reading frame. The polypeptides encoded by hsdSNgoAVΔT and hsdSNgoAVΔG are 406 aa long instead of 210 aa (Fig. 1, panels 2b and 2c). A nonrepeated 13-aa region, which is not present in the archetypal recognition subunits HsdSEcoR124I and HsdSEcoDXXI, occurs in these polypeptides (Fig. 1, panels 2a and 2c). This amino acid sequence, NQIGGDSDGYQCR, shares no homology with any polypeptide in the protein databases. To test the importance of this motif, a mutated form of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene was created by deletion of 39 nucleotides between positions 611 and 649 (carried by plasmid pMS2Δ40). The encoded polypeptide, HsdSNgoAVΔ40, is 393 aa long, and the organization of its central conserved domain is identical to that of archetypal IC HsdSs (Fig. 1, panel 2d). All of the hsdS mutants described above encode polypeptides with two TRDs and three CDs, like the archetypal HsdS subunits (Fig. 1, panel 2a).

The fusion subunits HsdSNgoAVΔT/G and wild-type HsdSNgoAV have different DNA specificities.

We have previously shown that the HsdS, HsdM, and HsdR subunits of the NgoAV RM system form an active restriction enzyme complex, even if encoded by different plasmids (3). Plasmid pR, carrying the hsdRNgoAV locus, was introduced into E. coli Top10 (restriction-deficient [r−], modification-deficient [m−]) cells, together with pMS2 or one of its mutated derivatives, pMS2ΔT, pMS2ΔG, or pMS2Δ40. The efficiency of plating (EOP) of the virulent form of bacteriophage λ (λvir) on these strains was tested. The results were compared to the EOP of λvir on E. coli Top10 lacking any RM system or on the strain carrying plasmid pNo12, encoding the complete, wild-type NgoAV RM system. As shown in Table 1, the E. coli cells expressing the wild-type HsdSNgoAV, mutant HsdSNgoAVΔT (plasmids pMS2ΔT plus pR, pNo12ΔT, and pSMRX), or mutant HsdSNgoAVΔG (pMS2ΔG plus pR) subunit all restricted the unmodified λ0 phage. The EOP values of around 10−3 PFU/ml were comparable to that for the strain carrying the complete wild-type system encoded by pNo12 (see Table 1 for details). E. coli cells expressing HsdSNgoAVΔ40 (pMS2Δ40 plus pR), which lacks the 13-aa motif in the CD, failed to restrict λ0: the EOP for this strain was 0.62 ± 0.5 PFU/ml.

The altered specificity of the constructed HsdS subunits was demonstrated by examining the λvir modification in vivo. Bacteriophage λvir, modified during propagation on strains expressing the NgoAV system, was restricted by cells expressing NgoAVΔT and NgoAVΔG at a level that was comparable to that for an unmodified phage (about 10−3 PFU/ml). Furthermore, after being modified by propagation on E. coli (pMS2ΔT or pMS2ΔG), λvir phage was restricted in cells carrying the wild-type NgoAV RM system (pNo12) at the same level. The specificity of the NgoAVΔT RM system did not depend on whether it was encoded by a low (pSMRX, a pACYC184 derivative)- or high-copy-number plasmid (pNo12ΔT, a pUC19 derivative). These results clearly demonstrated that plasmids pMS2ΔT and pMS2ΔG encode novel mutated and functional HsdS subunits with a recognition specificity different from that of wild-type HsdSNgoAV. It was found that both HsdSNgoAVΔT and HsdSNgoAVΔG subunits recognize the same DNA sequence, since the bacteriophage propagated on HsdSNgoAVΔT-expressing cells was protected from restriction in E. coli expressing NgoAVΔG (EOP = 0.84 ± 0.5 PFU/ml of λNgoAVΔT for pMS2ΔG plus pR). In the reciprocal test, the phage propagated on HsdSNgoAVΔG-expressing cells was protected from restriction in E. coli expressing NgoAVΔT (EOP = 1.1 ± 0.3 PFU/ml of λNgoAVΔG for pMS2ΔT plus pR). This RM system with novel specificity determined by fused specificity subunit was named NgoAVΔ.

Bacteriophage λ propagated on strains carrying plasmid pMS2Δ40 was restricted in E. coli Top10 strains carrying pNo12 or pNo12ΔT (Table 1), indicating that this plasmid does not encode a methyltransferase with NgoAV or NgoAVΔT specificity. The 13-amino-acid motif between subdomains C and D appears to be essential for functional activity (both modification and restriction) in the fused form of the HsdSNgoAV protein.

Subpopulation of N. gonorrhoeae cells expressing NgoAVΔ in vivo.

We failed to observe any PV of the NgoAV RM system cloned in E. coli by classical methods, such as the observation of a color change in cells expressing a translational fusion between the hsdSNgoAV1 and lacZ′ genes grown on X-Gal-containing plates. All colonies were light blue (data not shown), and cellular β-galactosidase activity levels measured in vitro showed negligible variation (>1,000 colonies examined; data not shown).

The PV reporter vector pMPMlacZ was constructed by cloning the lacZ′ gene into vector pMPMT4Ω under the control of the arabinose-inducible PBad promoter (Fig. 2). The resulting construct was used to confirm the occurrence of bacteria with 6 guanosines within the poly(G) tract present at the 3′ end of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene (Fig. 1, panel 1). Carefully designed primers were used to amplify the portion of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene which contains the poly(G) tract with high-fidelity PfuUltra DNA polymerase and clone it upstream of the lacZ′ gene. It was reasoned that the hsdSNgoAV1 and lacZ′ genes would be fused in frame and translated into a hybrid polypeptide able to perform α-complementation with the lacZΔM15 product present in E. coli Top10 cells (i.e., blue colonies on plates containing X-Gal and arabinose) only if the poly(G) tract in the amplified fragment contained 6 guanines. If the amplified fragment contained 7 guanines, the hsdSNgoAV1 and lacZ′ genes would not be fused in frame and the transformed E. coli cells would be white. The rationale of this strategy was tested using plasmids pMS2 (hsdSNgoAV1 with 7 guanines) and pMS2ΔG (6 guanines). As anticipated, when pMS2 plasmid DNA was used as the PCR template, the majority of the transformed cells produced white colonies (6.6% blue colonies, total of 256 colonies counted), whereas with pMS2ΔT/G as the template, the majority of colonies were blue (1.9% white colonies, 910 total colonies counted).The in vivo analysis of the number of guanosines within the poly(G) tract was performed using N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 chromosomal DNA as the template for amplifying this region of the hsdSNgoAV1 gene to be cloned into plasmid pMPMlacZ. In 8 independent experiments, in which a total of 5,482 clones were examined, almost 5.8% (+/−1.6%) of the colonies were blue. The sequencing of plasmid DNA isolated from a sample of the blue colonies confirmed the presence of 6 G residues in one-half of the sequenced DNAs. In the other cases, different nucleotide deletions had occurred, e.g., in homopolymeric tracts of 5 and 6 adenines present within the hsdSNgoAV1 gene.

These results demonstrated that a minor subpopulation of cells in N. gonorrhoeae cultures express NgoAVΔ specificity.

Determination of the recognition sequence of the NgoAVΔ RM system using an in vivo methylation test.

To determine the recognition sequence of NgoAVΔT, we used a method based on the assumption that the DNA sequence recognized by the methyltransferase can overlap the recognition sequence of a methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease(s). Some restriction enzymes are unable to cleave DNA containing a methylated adenine residue within their recognition sequences (REBASE; Fermentas). The presence of a site that is protected from cleavage by a particular methylation-sensitive enzyme will result in the loss of some predicted fragments and/or the appearance of an additional undigested fragment(s) after cleavage and electrophoresis.

Different plasmid DNAs, isolated from E. coli cells expressing the NgoAVΔ methyltransferase, were digested in vitro with a panel of 34 methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (see Materials and Methods for details), and the restriction fragments produced were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

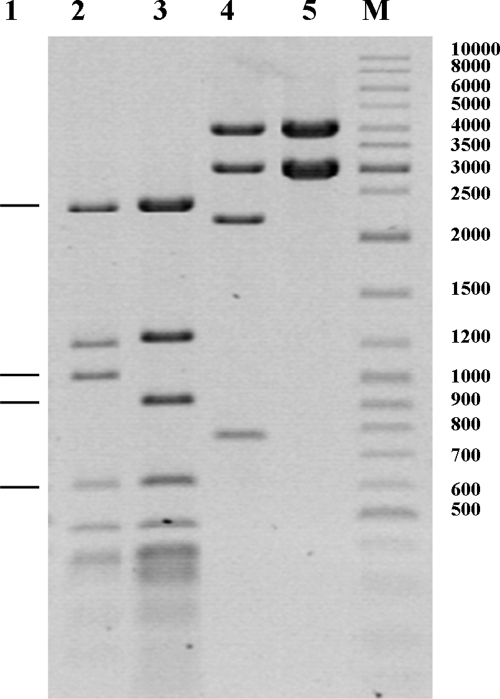

Among the panel of enzymes used, only HincII, LweI, and HinfI showed the presence of sites that were protected from digestion. Examples of the typical results of such an experiment are shown in Fig. 3. The theoretical gel banding pattern produced by digestion of unmethylated plasmids pNo12 and pNo12ΔT by LweI (GCATC) is shown in Fig. 3, lane 1. Cleavage would be predicted to generate fragments of 2,410, 1,052, 914, and 603 bp and 30 others of <500 bp. As expected, LweI cleavage of methylated pNo12 (lane 2), encoding the wild-type NgoAV RM system, produced a 1,219-bp fragment (lack of digestion to separate fragments of 914 and 305 bp). This indicated that the LweI site at nucleotide position 2542 overlaps the sequence 5′-GCA(N8)TGC-3′, recognized by NgoAV (3, 34). In the case of plasmid pNo12ΔT (lane 3), the predicted DNA fragment of 1,052 bp was missing and the undigested 1,243-bp fragment remained. The presence of this DNA fragment indicated that the LweI site at nucleotide position 8991 in pNo12ΔT is methylated by NgoAVΔ. The cleavage of plasmids pNo12 and pNo12Δ by HincII (GTYRAC) should produce 4 fragments (4,125, 3,030, 2,210, and 770 bp), and all of these predicted fragments were generated in the case of pNo12 (Fig. 3, lane 4).

Fig. 3.

Possible outcomes of LweI and HincII restriction digestion at an overlapping NgoAVΔT recognition site. Computer analysis indicated that digestion of unmethylated pNo12 or pNo12Δ plasmid DNA with LweI would result in 34 DNA fragments, with only four larger than 500 bp: 2,410, 1,052, 914, and 603 bp (lane 1). In the case of plasmid pNo12 digested by LweI, the 914-bp fragment was absent and was replaced by a 1,219-bp fragment (lane 2). For pNo12Δ, a fragment of 1,243 bp (the 1,052- and 191-bp fragments combined) appeared (lane 3). Cleavage of pNo12 or pNo12Δ with HincII should generate 5 fragments: 4,125, 3,030, 2,210, 770, and 42 bp. This pattern was observed following cleavage of pNo12 (lane 4). The cleavage of pNo12Δ did not resulted in the appearance of the 770- and 2,210-bp fragments, but the uncleaved fragment of 2,980 bp persisted (lane 5). The presence of this fragment was confirmed by a double digestion with HincII and Bpu1102I (data not shown). M, Fermentas molecular weight DNA ladder (GeneRuler DNA ladder mix).

On the other hand, cleavage of pNo12ΔT resulted in the absence of the 770- and 2,210-bp DNA fragments and the presence of the undigested 2,980-bp fragment, indicating the protection by methylation of the HincII site at nucleotide position 794 (Fig. 3, lane 5). The presence of this 2,980-bp fragment was confirmed by a double digestion with HincII and Bpu1102I, which recognizes only one site in pNo12ΔT, located within this undigested fragment (data not shown). A similar analysis showed that plasmid pL4 (pUC19 carrying a large cloned fragment of λ phage DNA), isolated from cells expressing NgoAVΔ (pSMRX), is protected against cleavage by HinfI at a site located at nucleotide position 1299. Furthermore, plasmid pNo12ΔT was digested by BseGI as predicted in silico (data not shown), suggesting that the BseGI recognition site (GGATG) does not overlap the NgoAVΔ methylation site, as it does that of NgoAV (4). These results confirmed the in vivo data indicating that the NgoAVΔ RM system recognizes a sequence different from that recognized by the wild type, NgoAV.

On the basis of the pattern of protection of plasmid DNA from cleavage by methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes and computer analysis of these sequences (listed in Table 2), the consensus sequence 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′ was designated the target sequence recognized by the NgoAVΔ methyltransferase (Table 2).

NgoAVΔ recognizes the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)STCA-3′.

In assays to characterize the recognition sequence of NgoAVΔ using ODN duplexes, a crude extract prepared from E. coli Top10 cells was employed. Double-stranded ODNs, whose sequences are listed in Table 3, were in vitro methylated by a crude cell extract (described in Materials and Methods) prepared from HsdSNgoAVΔ-expressing cells. The ODNs were designed in such a way that they did not contain sequences recognized by the native E. coli EcoKDam or EcoKDcm methyltransferases. The levels of incorporation of 3H are shown in Table 3. Two ODN duplexes, 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′ and 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′, were found to be effectively methylated by methylases present in crude extracts (∼80-fold and ∼30-fold above background, respectively), indicating recognition of the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)STCA-3′.

NgoAVΔ methylates 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′ only on one strand.

The ODN containing the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′ was cloned into the EcoRI/PstI sites of vector pUC19, and the resulting plasmid, pUColigoCTCA, contained two NgoAVΔ-specific sites: one with sequence 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′ (in the bla gene, at nucleotide position 1974) and one with sequence 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′ (nucleotide position 419). The plasmid was methylated in vivo by NgoAVΔT in E. coli Top10 cells carrying plasmid pSMRX. Plasmid DNAs were isolated, and pUColigoCTCA was gel purified (to separate it from pSMRX) and digested with restriction enzyme LweI or HinfI. Analysis of the resulting restriction fragments confirmed that, in the case of the 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′ sequence, only the adenine residue located in the right-hand part on the lower strand (complementary T in boldface) is methylated, whereas in the case of the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′, both 3′ and 5′ adenines in the motif are methylated (the adenine and the complementary thymine that are methylated are in boldface).

Indeed, cleavage of the unprotected pUColigoCTCA by LweI generated 9 DNA fragments: 1,052, 476, 359, 249, 191, 116, 94, 40, and 36 bp (Fig. 4, lane 1). Within the plasmid pUColigoCTCA sequence, two LweI sites (underlined) overlap two NgoAVΔ recognition sites: the 5′-GCAtcgtggtGTCA-3′ sequence at nucleotide position 1947 and the 5′-GCAtcgcggaCTCA-3′ sequence at position 419 (lowercase letters represent the nonspecific nucleotides within the recognized sequence). In the case of protection at position 1947, the undigested fragment of 1,243 bp (1,052 + 191 bp) would persist. In the case of protection at the second LweI site, the undigested 592-bp fragment would persist and the fragments of 476 and 116 bp would disappear. Figure 4, lane 2, shows the presence of the undigested 1,243-bp fragment and the 476- and 116-bp fragments, indicating that the GCATC LweI site is protected by NgoAVΔ methylation only in the context of 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′.

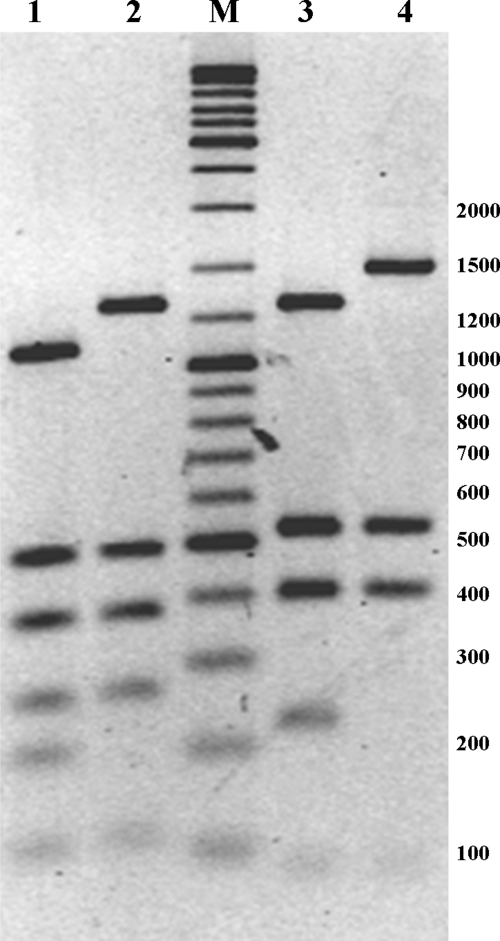

Fig. 4.

Possible outcomes of LweI and HinfI digestion at overlapping NgoAVΔT recognition sites in plasmid pUColigoCTCA. Plasmid pUColigoCTCA DNA, containing two NgoAV-specific sites, GCA(N7)GTCA (at nucleotide position 1947) and GCA(N7)CTCA (at nucleotide position 419), was isolated from E. coli Top10 cells expressing (lanes 2 and 4) or not expressing (lanes 1 and 3) NgoAVΔ. The digestion of nonmethylated pUColigoCTCA DNA with LweI is predicted to generate 6 fragments greater than 100 bp (lane 1). Following methylation by NgoAVΔ of the LweI site at nucleotide position 1947, a fragment of 1,243 bp appeared instead of the 1,052- and 191-bp DNA fragments (lane 2). In the same way, the site at position 419 should be protected from cleavage by LweI and a fragment of 592 bp should appear instead of fragments of 116 and 476 bp. The data (lane 2) show the lack of this uncleaved fragment. The HinfI digestion pattern of nonmethylated pUColigoCTCA is shown in lane 3 (fragments of 1,405, 517, 396, 215, 75, and 65 bp). The absence of fragments of 1,405 and 215 bp indicated that the site at position 419 is recognized and methylated by NgoAVΔ (lane 5). M, Fermentas molecular weight DNA ladder (GeneRuler DNA ladder mix).

However, the sequence 5′-GCAtcgcggaCTCA-3′ at nucleotide position 419 is apparently recognized by NgoAVΔ since the HinfI site (underlined) is protected against cleavage (the nucleotide specific for NgoAVΔ is in boldface). As shown in Fig. 4, lane 3, the digestion of nonmodified pUColigoCTCA by HinfI generates 6 fragments of 1,405, 517, 396, 215, 75, and 65 bp, as predicted by in silico DNA sequence analysis. In the case of methylation by NgoAVΔ, the HinfI site is protected from digestion, as is shown by the persistence of the 1,620-bp undigested DNA fragment rather than the appearance of the 1,405- and 215-bp fragments (Fig. 4, lane 4). In conclusion, within the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′, the first 5′ adenine residue is not methylated but the second 3′ adenine residue (on the lower strand) is methylated by NgoAVΔ.

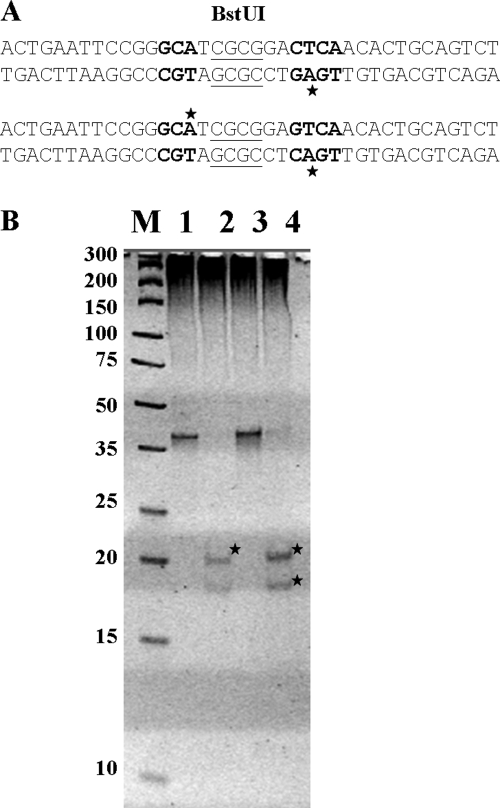

These observations were confirmed by the in vitro methylation of 38-bp ODN duplexes that included a BstUI recognition site (CGCG) within the nonspecific nucleotides of the NgoAVΔ recognition sequence (Fig. 5A shows the sequence). These assays permitted separate analyses of the 5′ and 3′ halves of the recognized sequence.

Fig. 5.

NgoAVΔ methyltransferase methylates only one adenine residue within the recognition site 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′. (A) Sequences of double-stranded ODNs (38 bp) containing a BstUI site (underlined) in the nonspecific nucleotide sequences. Specific nucleotides recognized by NgoAVΔ are in boldface. (B) ODN duplexes, methylated in vitro in the presence of [3H]AdoMet, were digested with BstUI, and the resulting fragments were separated by electrophoresis on an 18% polyacrylamide gel. The separate DNA fragments were eluted, and the incorporated radioactivity was counted. Lane 1, undigested ODNs containing the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′; lane 2, the same ODNs digested with BstUI into fragments of 20 bp (1,274 dpm) and 18 bp (21 dpm); lane 3, undigested ODN duplexes containing the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)GTCA-3′; lane 4, the same ODNs digested with BstUI into fragments of 20 bp (100 dpm) and 18 bp (400 dpm). The fragments that have incorporated radioactivity are marked with stars. The background radioactivity level was 18 dpm. M, Fermentas molecular weight DNA ladder (GeneRuler ultra-low-range DNA ladder mix).

Double-stranded ODNs were methylated in vitro by NgoAVΔ, separated from any unincorporated radioactivity, and digested with BstUI, and the cleavage products were separated by electrophoresis on an 18% acrylamide gel (Fig. 5B). The separated DNA fragments, of 18 and 20 bp, were then eluted from the gel and tested for the level of 3H incorporation. In the case of ODNs containing the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′, only the 20-bp fragment (5′-CGGACTCAACACTGCAGTCT-3′) was methylated (radioactivity level, 1,274 dpm) (boldface indicates nucleotides specific for NgoAVΔ). The fragment 5′-ACTGAATTCCGGGCATCGC-3′ contained no incorporated 3H (21 dpm, compared with the background level of 18 dpm). In comparison, incorporated 3H was detected in both cleavage products in the case of ODNs containing 5′-GCA(N7)GCTCA-3′ (100 and 400 dpm, respectively, with a level of 340 dpm for the undigested 3H-labeled methylated ODN). This result confirmed that only the one adenine residue is methylated within the 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′ recognition sequence.

DISCUSSION

Phenotypic variation in bacteria is often associated with the virulence of the strain. A number of genes of N. gonorrhoeae, the causative agent of sexually transmitted disease, have been described as being subject to PV (22, 32). These genes include those encoding type IV pili, HpuA protein, involved in hemoglobin utilization, the opacity (Opa) proteins, involved in adhesion to neutrophils, lactoferrin-binding protein (Lbp), involved in the acquisition of iron, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and many others (17, 22, 25, 32, 47). In general, most phase-variable bacterial genes have been predicted to be involved in the biosynthesis of surface structures, which is consistent with their role in phase variations, i.e., interactions between pathogen and host. The recently described PV of RM systems may be involved in modulating such gene expression (41).

Different molecular mechanisms of PV exist, including homologous or site-specific recombination and SSM on short sequence repeats. Both mechanisms have been shown to regulate the PV of type I and type III RM systems. For example, site-specific recombination causes switching between different hsdS subunits present in the Mycoplasma pulmonis genome. Moreover, in this case, the expression of hsdR and hsdM may be completely switched off, leaving these bacteria defenseless against bacteriophage infection (13). In Haemophilus influenzae Rd, the mod gene is subject to PV due to the presence of repeated 5′-AGTC-3′ sequences that expand and contract because of SSM. These changes in the number of repeats lead to shifting of the reading frame, which switches the expression on or off (10). Pasteurella haemolytica, the agent of bovine pneumonic pasteurellosis, also encodes a type III system, which exhibits phase variation due to the presence of a long variable repeat sequence within the mod gene (38). The type III RM system of Helicobacter pylori contains a polymeric C tract within the res gene that appears to act at both the transcriptional and translational levels (11). The most common mechanism of PV in Neisseria spp. is SSM during replication (40). This is also the case for two type III RM systems (4, 10, 15), and in this study we describe such a mechanism for the NgoAV system.

Over many years of working on NgoAV, we have observed that the NgoAV-modified λ bacteriophage became restricted in NgoAV-expressing E. coli cells, suggesting the change of specificity of this system (unpublished data). In 2005, Jordan and colleagues (25) presented a list of genes that may be controlled by PV in different laboratory strains of N. gonorrhoeae. Among other criteria, this list was based on the lengths of repeat tracts and variation in these lengths between different laboratory strains or within the same strain. Several genes with short (i.e., 7-nucleotide) homopolymeric repeats were classified as potentially subject to PV. These candidates included many genes encoding hypothetical proteins and also the hsdSNgoAV1 gene (25). In all these genes the length of the homopolymeric tracts varied between 6 and 10 nucleotides. The hsdSNgoAV gene was considered a very strong candidate for PV. In a previous study, we showed that N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 encodes a functional type IC RM system, NgoAV (34), which utilizes a naturally truncated form of the HsdS subunit, similar to those studied in in vitro-manipulated systems (1, 29, 31). As demonstrated in the present study, HsdSNgoAV may expand by the fusion of two truncated hsdS genes. It is important to note that NgoAVΔ is still an active endonuclease, as was shown in experiments examining the restriction of phage λ in vivo. However, our experiments in E. coli did not reveal any PV. This may be due to the fact that the NgoAV system encoded by plasmid pNo12 is expressed from neisserial promoters, which may be poorly recognized in E. coli, and/or that SSM is a rare event in E. coli cells (21, 44). The application of PCR for the detection of PV was successfully applied to Campylobacter jejuni, which has many genes with homopolymeric tracts (48). Products amplified by PCR accurately represent the polymorphism present in chromosomal DNA. The reporter vector system employed in the present study made it easy to visualize the number of guanosines within the poly(G) tract by colony color observation after the cloning of such products.

The biological significance of PV of RM systems remains unclear and for a long time has been associated with resistance to phage attacks (23). Attempts to identify functional connections between the phase variability of RM systems and other sets of genes subject to PV have been made (13). The most recently proposed mechanism was termed the “phasevarion,” where switching on or off of the H. influenzae type III mod gene modulates the expression of a number of unlinked genes encoding surface and stress proteins (15). The RM systems would be part of an epigenetic mechanism of PV. The epigenetic regulation of PV has been best described for the Dam methyltransferase found in diverse bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella spp. (9, 46). Three systems for epigenetic PV with the participation of Dam are now known, and all require additional regulatory proteins that affect Dam. Mutations in the dam gene in Salmonella strains lead to avirulence.

In the case of NgoAV, the expanded HsdSNgoAVΔ protein is responsible for the recognition of a new DNA sequence, 5′-GCA(N7)STCA-3′ (S = C or G). Unexpectedly, in the sequence 5′-GCA(N7)CTCA-3′, only the adenine residue in the left half of the recognition sequence is methylated. According to the model presented by Kneale and Murray (27, 33) the HsdS subunits bind two HsdM subunits and position them on the recognition sequence. Thus, it appears that the additional 13-amino-acid spacer sequence present in the expanded HsdS form may cause the lack of proper flexibility of the polypeptide and may not permit the correct positioning of the methylase subunits. This motif is essential for the functioning of the restored HsdS subunit and is not present in classical type IC HsdS subunits of RM systems, which always methylate adenine residues on both DNA strands (24, 31). The biological significance of changing the specificity of the NgoAV system remains unknown, but 916 sites are predicted for NgoAV in the N. gonorrhoeae genome, and only 340 sites would be recognized by NgoAVΔ. The genome is certainly undermethylated in NgoAVΔ-expressing bacteria, and the expression of many different genes may be affected, as has been demonstrated for type III RM systems (6, 15, 20, 41). In addition, PV of RM systems may aid phage defense (6). Phages evolve in response to host defense mechanisms and may acquire resistance to one RM system. Therefore, shutting down or switching the specificity of this host defense system reduces the selection pressure for resistant phages. Switching may also allow the bacterial host to acquire beneficial DNA (N. gonorrhoeae is naturally competent for homologous DNA), which may confer a fitness advantage by changing the type of incorporated DNA (8).

The observation that DNA modification can affect global gene expression may indicate that there is a trade-off between growth, which could be detrimentally affected by modification, and phage resistance. Such an explanation is, however, insufficient for N. gonorrhoeae since no free phages have been recognized for these bacteria (34).

The phenotypic switching of the described RM systems may be “controlled” by the interaction with the host. In M. pulmonis, variation in the hsdS gene is induced during colonization of the rat trachea in vivo (20). In the case of H. pylori, the PV of putative methyltransferase HpyIM is induced by contact with human gastric cells (12). The knockout of another RM system, HpyC1IR, encoded by H. pylori, is associated with decreased adherence to gastric epithelial cells (28). RM systems may be of major importance for bacterial pathogenesis, since adherence is essential for bacterial spread. The molecular mechanisms developed by N. gonorrhoeae to initiate infection differ between men and women since the niches to colonize are different (14). If NgoAV, similarly to the type III systems, is part of a phasevarion, it may play a role in N. gonorrhoeae infection and host colonization.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant no. NN301032634 and NN303816940). We acknowledge the Gonococcal Genome Sequencing Project supported by USPHS/NIH, grant no. AI38399.

We thank B. A. Roe, L. Song, S. P. Lin, X. Yuan, S. Clifton, T. Ducey, L. Lewis, and D. W. Dyer, University of Oklahoma.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 7 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abadjieva A., Patel J., Webb M., Zinkevich V., Firman K. 1993. A deletion mutant of the type IC restriction endonuclease EcoR1241 expressing a novel DNA specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4435–4443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abadjieva A., Webb M., Patel J., Zinkevich V., Firman K. 1994. Deletions within the DNA recognition subunit of M. EcoR124I that identify a region involved in protein-protein interactions between HsdS and HsdM. J. Mol. Biol. 241:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adamczyk-Poplawska M., Kondrzycka A., Urbanek K., Piekarowicz A. 2003. Tetra-amino-acid tandem repeats are involved in HsdS complementation in type IC restriction-modification systems. Microbiology 149:3311–3319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adamczyk-Poplawska M., Lower M., Piekarowicz A. 2009. Characterization of the NgoAXP: phase-variable type III restriction-modification system in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 300:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Argos P. 1985. Evidence for a repeating domain in type I restriction enzymes. EMBO J. 4:1351–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bayliss C. D., Callaghan M. J., Moxon E. R. 2006. High allelic diversity in the methyltransferase gene of a phase variable type III restriction-modification system has implications for the fitness of Haemophilus influenzae. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:4046–4059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bickle T. A. 2004. Restricting restriction. Mol. Microbiol. 51:3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bille E., et al. 2005. A chromosomally integrated bacteriophage in invasive meningococci. J. Exp. Med. 201:1905–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Broadbent S. E., Davies M. R., van der Woude M. W. 2010. Phase variation controls expression of Salmonella lipopolysaccharide modification genes by a DNA methylation-dependent mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 77:337–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Bolle X., et al. 2000. The length of a tetranucleotide repeat tract in Haemophilus influenzae determines the phase variation rate of a gene with homology to type III DNA methyltransferases. Mol. Microbiol. 35:211–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Vries N., et al. 2002. Transcriptional phase variation of a type III restriction-modification system in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184:6615–6623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donahue J. P., et al. 2000. Analysis of iceA1 transcription in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 5:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dybvig K., Sitaraman R., French C. T. 1998. A family of phase-variable restriction enzymes with differing specificities generated by high-frequency gene rearrangements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:13923–13928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwards J. L., Apicella M. A. 2004. The molecular mechanisms used by Neisseria gonorrhoeae to initiate infection differ between men and women. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:965–981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fox K. L., et al. 2007. Haemophilus influenzae phasevarions have evolved from type III DNA restriction systems into epigenetic regulators of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:5242–5252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fox K. L., Srikhanta Y. N., Jennings M. P. 2007. Phase variable type III restriction-modification systems of host-adapted bacterial pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1375–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghosh S. K., et al. 2004. Pathogenic consequences of Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilin glycan variation. Microbes Infect. 6:693–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gubler M., Bickle T. A. 1991. Increased protein flexibility leads to promiscuous protein-DNA interactions in type IC restriction-modification systems. EMBO J. 10:951–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gubler M., Braguglia D., Meyer J., Piekarowicz A., Bickle T. A. 1992. Recombination of constant and variable modules alters DNA sequence recognition by type IC restriction-modification enzymes. EMBO J. 11:233–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gumulak-Smith J., et al. 2001. Variations in the surface proteins and restriction enzyme systems of Mycoplasma pulmonis in the respiratory tract of infected rats. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1037–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henderson I. R., Owen P., Nataro J. P. 1999. Molecular switches—the ON and OFF of bacterial phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 33:919–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hill S. A., Davies J. K. 2009. Pilin gene variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: reassessing the old paradigms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:521–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoskisson P. A., Smith M. C. 2007. Hypervariation and phase variation in the bacteriophage ‘resistome.’ Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janscak P., Abadjieva A., Firman K. 1996. The type I restriction endonuclease R. EcoR124I: over-production and biochemical properties. J. Mol. Biol. 257:977–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jordan P. W., Snyder L. A., Saunders N. J. 2005. Strain-specific differences in Neisseria gonorrhoeae associated with the phase variable gene repertoire. BMC Microbiol. 5:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kellogg D. S., Jr., Peacock W. L., Jr., Deacon W. E., Brown L., Pirkle D. I. 1963. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J. Bacteriol. 85:1274–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kneale G. G. 1994. A symmetrical model for the domain structure of type I DNA methyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol. 243:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lehours P., et al. 2007. Genetic diversity of the HpyC1I restriction modification system in Helicobacter pylori. Res. Microbiol. 158:265–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. MacWilliams M. P., Bickle T. A. 1996. Generation of new DNA binding specificity by truncation of the type IC EcoDXXI hsdS gene. EMBO J. 15:4775–4783 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mayer M. P. 1995. A new set of useful cloning and expression vectors derived from pBlueScript. Gene 163:41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meister J., et al. 1993. Macroevolution by transposition: drastic modification of DNA recognition by a type I restriction enzyme following Tn5 transposition. EMBO J. 12:4585–4591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meyer T. F. 1991. Evasion mechanisms of pathogenic Neisseriae. Behring Inst. Mitt. 1991:194–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murray N. E. 2000. Type I restriction systems: sophisticated molecular machines (a legacy of Bertani and Weigle). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:412–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piekarowicz A., Klyz A., Kwiatek A., Stein D. C. 2001. Analysis of type I restriction modification systems in the Neisseriaceae: genetic organization and properties of the gene products. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1199–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Price C., Lingner J., Bickle T. A., Firman K., Glover S. W. 1989. Basis for changes in DNA recognition by the EcoR124 and EcoR124/3 type I DNA restriction and modification enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 205:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Price C., Pripfl T., Bickle T. A. 1987. EcoR124 and EcoR124/3: the first members of a new family of type I restriction and modification systems. Eur. J. Biochem. 167:111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roberts R. J., Vincze T., Posfai J., Macelis D. 2007. REBASE—enzymes and genes for DNA restriction and modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D269–D270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ryan K. A., Lo R. Y. 1999. Characterization of a CACAG pentanucleotide repeat in Pasteurella haemolytica and its possible role in modulation of a novel type III restriction-modification system. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:1505–1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sambrook J., Russell D. (ed.). 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saunders N. J., et al. 2000. Repeat-associated phase variable genes in the complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58. Mol. Microbiol. 37:207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Srikhanta Y. N., et al. 2009. Phasevarions mediate random switching of gene expression in pathogenic Neisseria. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Srikhanta Y. N., Fox K. L., Jennings M. P. 2010. The phasevarion: phase variation of type III DNA methyltransferases controls coordinated switching in multiple genes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:196–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stein D. C., Gunn J. S., Radlinska M., Piekarowicz A. 1995. Restriction and modification systems of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Gene 157:19–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torres-Cruz J., van der Woude M. W. 2003. Slipped-strand mispairing can function as a phase variation mechanism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:6990–6994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ullmann A., Jacob F., Monod J. 1968. On the subunit structure of wild-type versus complemented beta-galactosidase of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 32:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van der Woude M. W., Baumler A. J. 2004. Phase and antigenic variation in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:581–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van Putten J. P. 1993. Phase variation of lipopolysaccharide directs interconversion of invasive and immuno-resistant phenotypes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. EMBO J. 12:4043–4051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wassenaar T. M., et al. 2002. Homonucleotide stretches in chromosomal DNA of Campylobacter jejuni display high frequency polymorphism as detected by direct PCR analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 212:77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.