Abstract

KdgR has been reported to negatively regulate the genes involved in degradation and metabolization of pectic acid and other extracellular enzymes in soft-rotting Erwinia spp. through direct binding to their promoters. The possible involvement of a KdgR orthologue in virulence by affecting the expression of extracellular enzymes in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, the causal agent of rice blight disease, was examined by comparing virulence and regulation of extracellular enzymes between the wild type (WT) and a strain carrying a mutation in putative kdgR (ΔXoo0310 mutant). This putative kdgR mutant of X. oryzae pv. oryzae showed increased pathogenicity on rice without affecting the regulation of extracellular enzymes, such as amylase, cellulase, xylanase, and protease. However, the mutant carrying a mutation in an ortholog of xpsL, which encodes the functional secretion machinery for the extracellular enzymes, showed a dramatic decrease in pathogenicity on rice. Both mutants of kdgR and of xpsL orthologs showed higher expression of two major hrp regulatory genes, hrpG and hrpX, and the genes in the hrp operons when grown in hrp-inducing medium. Thus, both genes were shown to be involved in repression of hrp genes. The kdgR ortholog was thought to suppress virulence mainly by repressing the expression of hrp genes without affecting the expression of extracellular enzymes, unlike findings for the kdgR gene in soft-rotting Erwinia spp. On the other hand, xpsL was confirmed to be involved in virulence by promoting the secretion of extracellular enzymes in spite of repressing the expression of the hrp genes.

INTRODUCTION

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae causes bacterial leaf blight on rice in most areas of Asia and some areas of West Africa, Australia, Latin America, and the Caribbean (31). Since the whole-genome sequences of three X. oryzae pv. oryzae strains (KACC10331, MAFF311018, and PXO99A) have been reported (24, 35, 44), X. oryzae pv. oryzae has been used as one of the model organisms to study plant-pathogen interactions, bacterial race differentiation, and evolution of plant pathogens (8, 47). So far, many genes of X. oryzae pv. oryzae have been suggested to be associated with pathogenesis (9, 10, 20), and many regulatory proteins, such as OryR, PecS, and LrpX (18, 26, 35), have been shown to be involved in regulation of these pathogenicity-related genes.

The IclR proteins, first identified in Escherichia coli, have been reported to be bacterial transcriptional regulators (22, 59). Members of the IclR family have been reported to regulate a wide variety of processes: carbon metabolism in the enterobacteriaceae (46), degradation of aromatic compounds in soil bacteria (4), inactivation of quorum-sensing signals in Agrobacterium (61), and plant virulence in certain members of the enterobacteriaceae (6, 32, 34). KdgR, one of the IclR proteins, was experimentally proved to regulate the expressions of pectin acetylesterase (encoded by paeX) and pectate lyase isozymes (encoded by pelA, pelB, pelC, pelD, pelE, and pelZ) in a plant-pathogenic enterobacterium, Dickeya dadantii (syn. Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937) (28, 29, 40, 42, 43, 48). In vitro analysis demonstrated that KdgR binds directly to the promoter regions of the in vivo-controlled genes (51). KdgR was also found in other plant-pathogenic enterobacteria: Erwinia carotovora (syn. Pectobacterium carotovorum) and Erwinia amylovora (28, 51). Furthermore, KdgR was reported to have a wider range of targets, and its role may not be restricted to pectinolysis (15, 23).

Since KdgR is the regulator of the genes involved in pectin catabolism and in the Out system (required for passing through the outer membrane as part of the type II secretion system [T2SS]) in D. dadantii (6, 20), the possible involvement of the latter function (i.e., secretion of extracellular enzymes) for virulence in X. oryzae pv. oryzae was suspected. To test this possibility of the role of kdgR, the strain carrying a mutation in xpsL, which is involved in the T2SS (10), was examined as the control of deficiency in secretion of extracellular enzymes.

Here a KdgR orthologue of X. oryzae pv. oryzae (KdgRxoo) was shown to be involved in pathogenicity without effects on the regulation and secretion of extracellular enzymes. Type III secretion systems (T3SS) are key virulence determinants used by proteobacteria to deliver effector proteins directly into the host cell cytoplasm (12). Many Gram-negative phytopathogenic bacteria possess hrp genes encoding type III secretion systems that deliver virulence and avirulence factors from the bacteria to plant cells and are required for pathogenesis in host plants and for triggering a hypersensitive response (HR) in nonhost and resistant plants (12, 50, 60). Thus, the possible involvement of KdgRxoo in the regulation of T3SS was studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth media, and chemicals.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. X. oryzae pv. oryzae and Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri strains were routinely grown at 27°C in YP medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, pH 6.8) and used for pathogenicity and HR tests. These tests were done also using the cells grown in hrp-inducing medium (for X. oryzae pv. oryzae) XOM2 [0.18% xylose, 14.7 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM sodium glutamate, 5 mM MgCl2, 670 μM methionine, 240 μM Fe(III)-EDTA, and 40 μM MnSO4], which induces the expressions of hrp genes (53). E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% NaCl, pH 7.0) at 37°C. The optical density (OD) of the bacterial culture was measured at the wavelength of 660 nm using a Bactomonitor BACT-500 instrument (Intertech, Tokyo, Japan). When required, antibiotics were added at the following final concentrations: rifampin at 100 μg/ml, ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, kanamycin at 50 μg/ml, and gentamicin at 100 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−endA1 hsdR17(rK+ mK−) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 φ80dlacZΔM15Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | BRL Co. |

| S17-1(λpir) | Tpr SmrrecA thi pro hsdR M+ RP4:2-Tc:Mu-Km:Tn7 λpir | Biomedal |

| BL21(DE3) | F−dcm ompT hsdS gal(DE3) | Novagen |

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae | ||

| T7174R | Spontaneous mutant of T7174, used as the wild-type strain, Rfr | 55 |

| ΔXoo0310 mutant | Deletion mutant of T7174R (in ORF Xoo0310 [encoding orthologue of KdgR of D. dadantii]), Rfr | This study |

| CΔXoo0310 mutant | Complementary mutant of ΔXoo0310 strain, Rfr | This study |

| ΔxpsL mutant | Transposon insertion mutant of T7174R, a type II mutant of T7174R, Rfr Kmr | 10 |

| Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri | ||

| NA-1 | Wild-type, Rfr | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | T-A cloning vector, lacZ, Apr | Promega |

| pGEM-T | T-A cloning vector, lacZ, Apr | Promega |

| pUFR047 | Broad-host-range vector, Gmr | 5 |

| pJQ200SK | Suicide vector, mob+, Gmr | 37 |

| pET21a(+) | T7 overexpression vector, Apr | Novagen |

| pGEMDEL0310 | 798-bp DNA fragment with 345-bp deletion in kdgR coding sequence in pGEM-T Easy, Rfr Apr | This study |

| pJQDEL0310 | pJQ200SK plasmid containing 798-bp DNA fragment with 345-bp deletion in kdgR coding sequence, Rfr Apr | This study |

| pGEMkdgR | pGEM-T Easy plasmid with 777-bp PCR fragment containing kdgR of T7174R, Apr | This study |

| pETkdgR | pET21a(+) with 777-bp fragment containing KdgR coding sequence, Apr | This study |

| pET-NA-kdgR | pET21a(+) with 750-bp fragment containing X. axonopodis pv. citri KdgR coding sequence, Apr | Laboratory collection |

| pGEMCkdgR | pGEM-T Easy plasmid with 1,377-bp PCR fragment containing promoter region and whole coding region of kdgR of T7174R, Apr | This study |

| pUFRCkdgR | pUFR047 plasmid with 1,377-bp PCR fragment containing promoter region and whole coding region of kdgR of T7174R, Gmr Apr | This study |

| pGEM338bp | pGEMT-T plasmid containing 338-bp promoter fragment of hrpG, T7174R, Apr | This study |

| pGEM345bp | pGEMT-T plasmid containing 345-bp promoter fragment of hrpX, T7174R, Apr | This study |

| pGEM236bp | pGEMT-T plasmid containing 236-bp promoter fragment of hrpG, NA-1, Apr | This study |

| pGEM271bp | pGEMT-T plasmid containing 271-bp promoter fragment of hrpX, NA-1, Apr | This study |

| pGEMdelhrpG | pGEMT-T plasmid containing 760-bp promoter fragment with a 60-bp deletion in hrpG promoter, T7174R, Apr | This study |

| pGEMdelhrpX | pGEMT-T plasmid containing 651-bp promoter fragment with a 50-bp deletion in hrpX promoter, T7174R, Apr | This study |

Apr, Rfr, and Kmr indicate resistance to ampicillin, rifampin, and kanamycin, respectively.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Most recombinant techniques, such as preparation of plasmid and chromosomal DNA, PCR, restriction endonuclease digestion, gel electrophoresis, and DNA ligation, were done as described by Ausubel et al. and by Sambrook et al. (1, 45). The restriction and modification enzymes used in this study were purchased mostly from Nippon Gene (Tokyo, Japan) and from New England BioLabs (Beverly, MA). The sequence of DNA was determined using a CEQTM 2000XL DNA analysis system (Beckman and Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Construction of strain carrying mutation in ortholog of kdgR.

The kdgR nonpolar in-frame deletion mutant (Xoo0310 mutant [ΔXoo0310]; MAFF311018) was constructed by the splicing-by-overlap-extension (SOE) technique as described by Horton et al. and Lefebvre et al. (14, 25). Briefly, fragments of Xoo0310 encoding the N-terminal (399-bp) and C-terminal (399-bp) regions were amplified by PCR using the primer pair NK-FP (5′-GTCGACtgcaatcgggcgagcgtactgcgc-3′) (capital letters indicate the SalI recognition site) and NK-RP (5′-gccatcggcatcgcgcatcaggta-3′) and the primer pair CK-FP (5′-cgcgatgccgatggcgacctgacc-3′) and CK-RP (5′-GTCGACtattgccgggtgcgagacaggctg-3′) (capital letters indicate the SalI recognition site), respectively. It should be noted that the primer pairs of NK-RP and of CK-FP contain a 15-bp complementary sequence at their 5′ ends. These two fragments were purified using a Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) after agarose gel electrophoresis and then annealed. The fragment was thus constructed with a 345-bp in-frame deletion in Xoo0310, which corresponds to amino acids 134 to 248 (a conserved domain in the IclR family). The purified fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to construct pGEMDEL0310 (Table 1) and was confirmed by sequencing. The plasmid pGEMDEL0310 was digested with SalI, and the purified fragment was ligated into the same site of pJQ200SK (suicidal vector with selectable markers, Gmr, and a sacB gene conferring sucrose susceptibility) (38) to create pJQDEL0310. The plasmid pJQDEL0310 was delivered into the X. oryzae pv. oryzae wild-type strain T7174R through biparental mating with E. coli S17-1 (λpir) as a donor strain as described by Shen and Ronald (47). A single-crossover recombinant (Gmr sucrose susceptible), confirmed by PCR, was used to isolate the ΔXoo0310 mutant by double homologous recombination as described by Chatterjee et al. (5). The ΔXoo0310 deletion was confirmed by PCR amplification of shortened fragments comparing to that of the wild type and Southern blotting using the 345-bp deleted part of Xoo0310 as the probe.

Complementation of ΔXoo0310 mutation.

For the complementation test, a 1,377-bp genomic DNA fragment containing the entire coding region of Xoo0310 (including 300 bp upstream from the start codon and 300 bp downstream after the stop codon) was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of the wild-type strain T7174R as the template using primers C-FP (5′-GAATTCgtcgttgaggttgttggccatgccccataa-3′) and C-RP (5′-GAATTCagcagtgtaacaacgcaaaaccggttttcg-3′) (capital letters in each primer indicate the perturbed sequence of the EcoRI cut). The amplified fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector, and the plasmid, pGEMCkdgR, was obtained. The EcoRI fragment was then recloned into a broad-host-range plasmid, pUFR047, to obtain the plasmid pUFRCkdgR. This construct was then introduced into the ΔXoo0310 mutant to generate the complemented (CΔXoo0310) strain.

Enzyme assays for extracellular enzymes.

Plate assays for extracellular enzymes, such as pectate lyase, polygalacturonase, amylase, cellulase, xylanase, and protease, were carried out as described by Matsumoto et al. (30). In brief, bacterial strains were grown in YP medium until an OD at 660 nm (OD660) of 1.0 was reached. One milliliter of culture was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min to remove the cell debris. For the amylase assay, the culture suspension without centrifugation was sonicated twice for 20 s each time (UD-200 ultrasonic disrupter; Tomy, Tokyo, Japan) on ice and then centrifuged to remove the cell debris. Then, 50 μl of the supernatant was placed in the wells by digging the plates (1% polygalacturonic acid, 50 μM CaCl2, and 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, for pectate lyase; 1% polygalacturonic acid, 2.2 mM EDTA, and 0.1 M sodium acetate for polygalacturonase; 0.2% soluble starch for amylase; 0.1% carboxymethyl cellulose for cellulase; 0.1% xylan for xylanase; and 2% glycerol and 1% skim milk for protease) using a cork borer. The halos around the wells were observed after overflowing with visualizing solutions (4 N H2SO4 for pectate lyase and polygalacturonase; 0.3% I in 1% KI for amylases; 1 mg/ml Congo red for cellulase and xylanase) after 48 h of incubation at 27°C.

Pathogenicity and HR test.

Rice cultivar IR24 was grown in a greenhouse for 30 to 40 days and transferred at least 1 day before inoculation into a growth chamber with light for 16 h at 27°C and in the dark for 8 h at 25°C with 70% relative humidity. X. oryzae pv. oryzae strains were grown on YP medium for 3 days at 27°C, resuspended in sterile distilled water at a cell density of approximately 109 CFU/ml, and used for the inoculation. Rice leaves were inoculated with the scissor-clip method (namely, the tip of the leave was cut and dipped in the bacterial suspension) (21) and incubated in the growth chamber at 27°C. Lesion areas formed were calculated at 14 days after inoculation.

The in planta bacterial cell number was determined as described by Islam et al. (18). Briefly, the inoculated leaves were cut into small pieces (1 mm by 10 mm) and ground in 1 ml sterile distilled water with a sterile mortar and pestle. The suspension was diluted serially and spread on a YP plate containing appropriate antibiotics. Bacterial colonies were counted after a 4-day incubation at 27°C.

For the hypersensitive response (HR) test, the tobacco cultivar Xanthi was grown in a greenhouse for about 30 days. X. oryzae pv. oryzae strains were grown in YP medium for 3 days at 27°C, centrifuged and resuspended in double-distilled water (DDW) at a cell density of approximately 107 CFU/ml. Tobacco leaves were infiltrated in their intracellular area with 100 μl of the bacterial suspension using a sterile needless syringe and incubated at room temperature for 24 h.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, MD), RNA was extracted from the bacterial cells after being grown in the appropriate medium and harvested at the early exponential growth phase (OD660 = 0.4). The purity and concentration of RNA were determined with a microspectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed for 40 min at 37°C using random 12-mer oligonucleotides according to the Omniscript kit manual (Qiagen). The cDNA solutions were diluted 1/15, and aliquots were stocked at −20°C until use.

Expression of hrp genes and hrp regulatory genes was measured by quantitative PCR. The amplification was performed a Max Pro Mx3000P instrument (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). Primers were designed based on the genome sequence of X. oryzae pv. oryzae strain T7174R MAFF311018, and sequences are shown in Table 2. Primer specificity was assessed using the dissociation curve protocol for the Mx3000P Multiplex quantitative PCR system. PCR amplification conditions were as follows: denaturing at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles. Each PCR experiment was performed in triplicate, and the standard deviation was calculated. Relative values of transcriptional levels were calculated using the ΔΔCT method as previously described (29). The fluorescence intensity of SYBR green at each point of the annealing phase was measured automatically, and the threshold cycle (CT) of each sample was calculated. The calculated CT data were used for quantitative analysis by the comparative CT method. For each amplification run, the calculated CT value for each gene amplification was normalized to the CT value of the 16S rRNA gene amplified from the corresponding sample before calculating the difference (fold) between the wild type and the mutant using the following formula: fold change = 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT for gene j = (CTj − CT,16S rRNA)mutant − (CTj − CT,16S rRNA)wild type.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| hrpG-F | CACACGGATCGGCGTTTCT |

| hrpG-R | AACGCTGAGTTGCTGCGT |

| hrpX-F | GTCTTACGCAGAACGTCTTCC |

| hrpX-R | CTGGCCCAGATGAAAGTGGGTC |

| hrpE-F | ATGGAAATACTTCCGCAAATCAGCTCAC |

| hrpE-R | TTACTGGCCAACGAGCTGCTTAG |

| hrcQ-F | ACTACGCGTTTCGATCGCGG |

| hrcQ-R | GCACGCAATACCGCGCCT |

| hrcU-F | TTCCTGGCTGCGTGCCTG |

| hrcU-R | TGACCACCATCACCTTGGCC |

| hrpB1-F | CGGTCGTGAGTGGGCTCA |

| hrpB1-R | TCAGGCGCGCAGGTACTG |

| hrcV-F | GCCATGGTGTCGCAGATCG |

| hrcV-R | TGACGGCCGATATCGAGCC |

| hrpF-F | CCAGGTCGACTCGCTGTC |

| hrpF-R | GATCAACTGCGGTGGGCA |

| 16S rRNA-F | GTTGTGAAAGCACTGGGCTCAACCT |

| 16S rRNA-R | CATCTCACGACACGAGCTGACGACA |

Overexpression of KdgRxoo and X. axonopodis pv. citri KdgR (KdgRxac).

The X. oryzae pv. oryzae kdgR ortholog was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of X. oryzae pv. oryzae strain T7174R using primers KdgR-FP (5′-CATATGagcaccgaacacgccaagtaccgcgcg-3′) (capital letters indicate the NdeI recognition site) and KdgR-RP (5′-GAATTCatgtcctagcgcgcggggcgggtggta-3′) (capital letters indicate the EcoRI recognition site). The amplified fragment was ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) to construct the plasmid pGEMkdgR and then subcloned into the NdeI and EcoRI sites of pET21a(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI) to generate a construct (pETkdgR) which forms KdgRxoo with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag (His tag). A construct carrying X. axonopodis pv. citri KdgR with a His tag, pET-NA-kdgR, was generated using the same method. Both constructs were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to generate strains BLkdgR and BL-NA-kdgR, respectively.

To overexpress the KdgRxoo and KdgRxac proteins, E. coli clones BLkdgR and BL-NA-kdgR were grown at 37°C, and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM, final concentration) was added to induce protein synthesis. The centrifuged cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (NaCl [137 mmol/liter]–KCl [2.7 mmol/liter]—Na2HPO4 [4.3 mmol/liter]–KH2PO4 [1.4 mmol/liter], pH 7.2) buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and then disrupted by sonication on ice using an Ultrasonic UD-200 disruptor with duty 40 and input 4 for 5 min with 5-min intervals. The sonicated suspension was filtered through Steradisc 25 (pore size, 0.45 μm; Kurabo, Osaka, Japan), and crude extracts were purified on a 1-ml HiTrap chelating column as instructed by the manufacturer (His Trap HP kit; GE Healthcare Bio-sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

The electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described by Ausubel et al. (1) with the following modifications. The 338-bp and 345-bp fragments in the X. oryzae pv. oryzae promoter region of hrpG (GGTCT- to -ACGGA) and of hrpX (GGTCA- to -CTCTG) were amplified, respectively, by PCR with the primer set Xoo-p-hrpG-FP (5′-GGTCTATACCTTGGCGGCTGTG-3′) and Xoo-p-hrpG-RP (5′-TCCGTGTGCAAGGGGGCAAG-3′) and that of Xoo-p-hrpX-FP (5′-GGTCAATGGCTGTGGAAGCGG-3′) and Xoo-p-hrpX-RP (5′-CAGAGATCGCTGCAAAGTAGGTCG-3′) and was cloned in pGEM-T vector (Promega) to generate plasmids pGEM338bp and pGEM345bp, respectively (Table 1). The 236-bp and the 271-bp fragments from the X. axonopodis pv. citri promoter of hrpG (GCTAA- to -CGACC) and of hrpX (CTCAA- to -TTGTC) were amplified, respectively, by PCR with the primer set Xac-p-hrpG-FP (5′-GCTAAAGCCGCTGGCGACAAAT-3′) and Xac-p-hrpG-RP (5′-GGTCGTTCATTTAGGCGGCCTTC-3′) and that of Xac-p-hrpX-FP (5′-CTCAACCGGATGGCGCGAAATG-3′) and Xac-p-hrpX-RP (5′-GACAACGCAGAGATCGCTGCAAAG-3′) and cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega) to generate plasmids pGEM236bp and pGEM271bp, respectively (Table 1).

For deletion of the KdgR-binding box in the promoter regions of hrpG of X. oryzae pv. oryzae, a mutant was constructed by the overlap extension (SOE) technique as described by Horton et al. (14) and Lefebvre et al. (25). Briefly, the two fragments were amplified by PCR using the pair Xoo-phrpG-del-1F (5′-ACCTCACTCTGTTCTCAAACGAGC-3′) and Xoo-phrpG-del-1R (5′-TTGCGAACGCTTCTTACGGGCATGT-3′) and the pair Xoo-phrpG-del-2F (5′-AAGAAGCGTTCGCAAGCGTGAAAC-3′) and Xoo-phrpG-del-2R (5′-GTCGAAGACCAGTAACTCGCAC-3′), purified using a Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) after agarose gel electrophoresis, and annealed to each other by second PCR using the pair Xoo-phrpG-del-1F and Xoo-phrpG-del-2R at 60.5°C. The fragment was thus constructed to contain a 60-bp deletion in the hrpG promoter of X. oryzae pv. oryzae. The purified fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to generate the plasmid pGEMdelhrpG (Table 1).

For deletion of the KdgR-binding box in the promoter regions of hrpX, a mutant was constructed using the same SOE method with the pair Xoo-phrpX-del-1F (5′-CAATTCGGCTGCGCGCTAGGT-3′) and Xoo-phrpX-del-1R (5′-ACAATCGCCGAGCTCAGAGACTG-3′) and the pair Xoo-phrpX-del-2F (5′-GAGCTCGGCGATTGTTGTCTTTTGC-3′) and Xoo-phrpX-del-2R (5′-CGGTATTCCGGCACGACAGCA-3′). The two fragments were then purified and annealed to each other by a second PCR using the pair Xoo-phrpX-del-1F and Xoo-phrpX-del-2R at 62°C. The fragment thus constructed contains a 50-bp deletion in the hrpX promoter X. oryzae pv. oryzae. The purified fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T vector to generate the plasmid pGEMdelhrpX (Table 1).

The correct directions of the insertion of pGEMdelhrpG and pGEMdelhrpX were confirmed and used as templates. The promoter regions were amplified by PCR using the primer sets Xoo-p-hrpG-FP/Xoo-p-hrpX-FP/Xac-p-hrpG-FP/Xac-p-hrpX-RP/Xoo-phrpG-del-1F/Xoo-phrpX-del-1F and the T7 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) primer labeled with the florescent dye rhodamine at the 5′end (FASMAC, Atsugi, Japan). The labeled hrpG, hrpX, delhrpG, and delhrpX promoter fragments were purified from the agarose gel after the electrophoresis using a GFXTM PCR DNA and gel band purification kit (GE Healthcare). For the gel mobility shift assay, 20 nM labeled promoter fragments and an appropriate concentration (50 nM to 500 nM) of the purified X. oryzae pv. oryzae or X. axonopodis pv. citri KdgR protein were mixed and incubated in a binding buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 50 mM KCl, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 3.75% glycerol, and 50 ng/μl poly(dI-dC) [Sigma-Aldrich]). After incubation for 30 min at 27°C, the reaction mixture was loaded into the well of a 4% polyacrylamide gel in high-ionic-strength buffer (1× Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE]), and electrophoresis was carried out in the same buffer for 3 h. The gel was then visualized with a Pharos FX PlusLaser molecular imager using the Quantity One one-dimensional (1-D) gel analysis software program (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

RESULTS

Construction of ΔXoo0310 mutant.

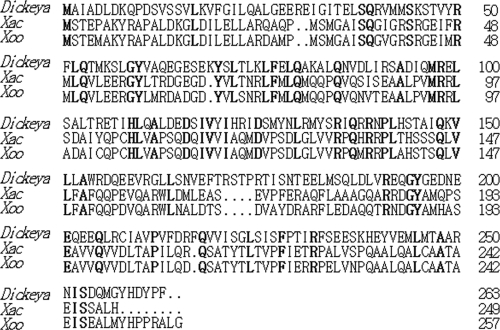

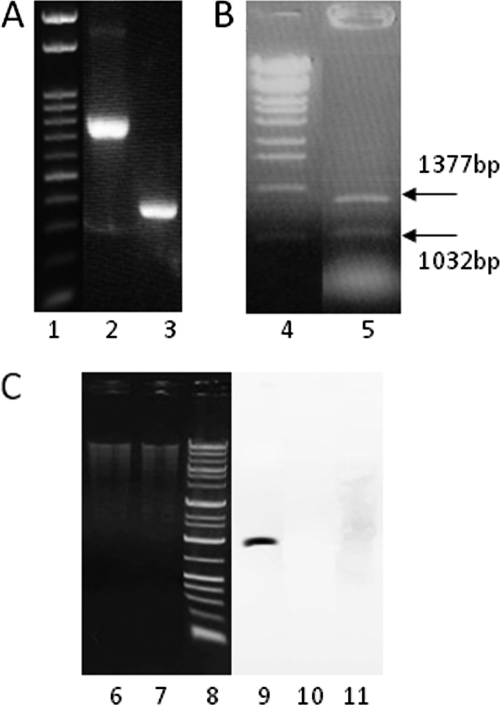

BLAST-P software indicated that the amino acid sequence (NCBI identifier [ID] 3856793) of the kdgR ortholog in X. oryzae pv. oryzae showed 22% homology to that of KdgR in the D. dadantii strain (NCBI ID 8090652) and showed 82% homology with that of the X. axonopodis pv. citri strain (NCBI ID 1158262) (Fig. 1). Also, an NCBI conserved domain search suggested that these two Xanthomonas species KdgR orthologues were shown to contain WHTH_GntR in common among the IcIR superfamily, which is described as a DNA-binding transcriptional repressor functional domain, like KdgR of D. dadantii. Thus, we considered these open reading frames (ORFS), ORF Xoo0310 and ORF Xac4191, to be the putative KdgR sequence. The ΔXoo0310 mutant was confirmed by the reduced molecular weight (MW) of the PCR product compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 2A), by Southern blotting using 345 bp in the deleted part as the probe (Fig. 2C), and by sequencing the PCR product obtained from the deletion mutant (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of KdgR proteins of D. dadantii (Dickeya), X. axonopodis pv. citri (Xac), and X. oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo). Boldface type indicates consensus sequences.

Fig. 2.

Confirmation of Xoo0310 deletion mutation and complementation mutant. (A) The 345-bp deletion of ΔXoo0310 was confirmed by comparing its smaller size (lane 3; 432 bp) of PCR-amplified fragment to that of the wild type (lane 2; 777 bp). Lane 1, 1-kb ladder. (B) Confirmation of CΔXoo0310 complementation construct. The mutant was confirmed by observing the double bands (one from a 345-bp-deletion mutant on the chromosome and another from the 1,377-bp fragment in a plasmid) after PCR amplification (lane 5). Lane 4, MW standard of OneSTEP Ladder 500. (C) Confirmation of ΔXoo0310 by Southern blot hybridization. EcoRI-digested total genome DNA of the wild type (lane 6) and the ΔXoo0310 mutant (lane 7) was blotted on the membrane and hybridized with the 345-bp probe. Wild-type DNA shows hybridized binding (lane 9), while ΔXoo0310 DNA does not (lane 10). Lanes 8 and 11, MW standard of 50-bp ladder.

Virulence test.

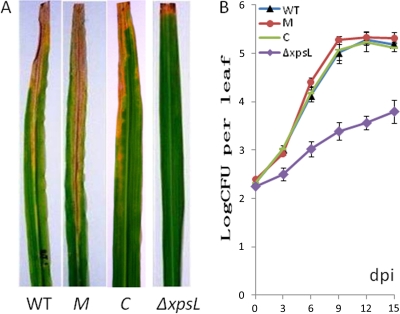

When the ΔXoo0310 mutant, CΔXoo0310 complementary strain, ΔxpsL mutant, and wild type were inoculated by the scissor-clip method onto the leaves of the rice cultivar IR24, the lesion area caused by the ΔXoo0310 mutant was significantly larger than that caused by the wild type (T7174R), and the lesion area caused by the CΔXoo0310 complementary strain was restored to the wild-type phenotype, while the ΔxpsL mutant showed a dramatically reduced lesion area (Table 3 and Fig. 3A). Thus, the mutation in the kdgR ortholog of X. oryzae pv. oryzae may result in enhancement of virulence. This enhancement may probably be due to the derepression of unidentified pathogenicity-related genes.

Table 3.

Lesion areas caused by wild-type and mutant strains on susceptible rice (IR24)

| Strain or genotypea | Lesion area (cm2)b | Relative area (%)c |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 2.3 ± 0.2 a | 100 |

| M | 8.0 ± 0.15 b | 348 |

| C | 2.0 ± 0.2 a | 87 |

| ΔxpsL | 0.35 ± 0.04 b | 15 |

WT, wild type; M, ΔXoo0310 strain; C, CΔXoo0310 complement strain; ΔxpsL, xpsL mutant strain.

Lesion area is the mean ± SD for three independent experiments, each with five leaves. Lesion areas were measured at 14 days after inoculation. Different letters indicate the significant difference at a P value of <0.05, and a t test of significance was performed.

Relative areas are expressed in percentages, with that for the wild type set as 100%.

Fig. 3.

Pathogenicity and in planta population. (A) Symptoms on rice leaves 14 days after inoculation by the scissor-clip method by dipping in 109 CFU/ml. WT, wild type; M, ΔXoo0310; C, CΔXoo0310 complement strain; ΔxpsL, xpsL mutant strain. (B) Population in rice leaves, expressed as CFU per leaf, from analysis repeated in triplicate. WT, wild type; M, ΔXoo0310; C, CΔXoo0310 complement strain; ΔxpsL, xpsL mutant strain. Error bars indicate standard deviations (±) for data from three independent experiments.

Complementation test.

For the complementation test, a 1,377-bp DNA fragment containing the promoter region and the entire coding region of Xoo0310 was cloned into the broad-host-range vector pUFR047 (pUFRCkdgR) and then transformed into the ΔXoo0310 mutant to generate the CΔXoo0310 strain, which was confirmed by observation of the double bands after PCR (Fig. 2B). The CΔXoo0310 complemented strain produced a lesion area on rice similar to that produced by the WT, suggesting that the CΔXoo0310 strain can resuppress the enhanced virulence of the mutant strain (Table 3 and Fig. 3A). Also, the in planta population showed the CΔXoo0310 strain resuppressed the level of the mutant to that of the wild type in rice leaves (Fig. 3B).

Total extracellular enzyme activities.

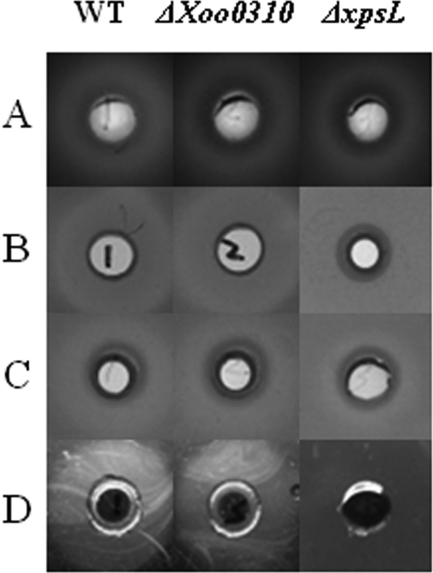

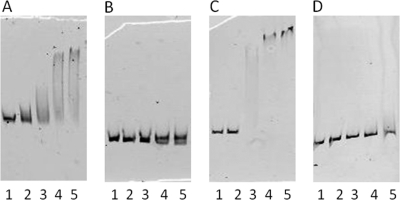

No activity of pectate lyase or of polygalacturonase was detected in the X. oryzae pv. oryzae WT by the present assays (data not shown). In fact, the genomics data indicate no orthologs of these enzyme genes in the X. oryzae pv. oryzae MAFF311018 genome (http://microbe.dna.affrc.go.jp/Xanthomonas/). Total activities (sonicated culture suspension) of amylase were detected, but no difference was detected among those of the WT, the ΔXoo0310 mutant, and the ΔxpsL strain (Fig. 4A). The total activities of cellulase, xylanase, and protease were detected, and there were no significant differences between those of the WT and ΔXoo0310 strains, while the ΔxpsL mutant strain showed almost an absence of activities in the supernatants (Fig. 4 B, C, D). Thus, KdgRxoo may not be involved in the regulation of these extracellular enzymes, and their secretion depends on a functional xpsL gene.

Fig. 4.

Total extracellular enzyme activities, determined in specific plate assays. (A) amylase (sonicated bacterial cell suspension); (B) cellulase; (C) xylanase; (D) protease. All the assays were repeated in triplicate with similar results.

KdgR regulates expression of hrp genes.

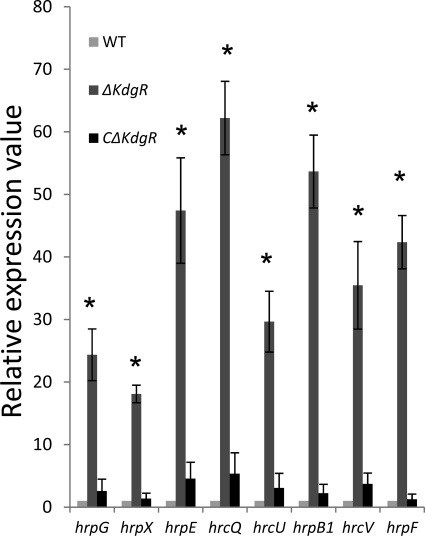

The hrp genes were reported to be regulated mainly by their major regulator genes, hrpG and hrpX, in Xanthomonas spp. (11, 54, 57). The expression of hrp genes together with that of hrpG and hrpX was examined in the ΔXoo0310 mutant, the CΔXoo0310 complemented mutant, and the ΔxpsL strain by RT-PCR analysis. The expression of hrpG, hrpX, and other hrp regulons, such as hrpE (Xoo0100), hrcQ (Xoo0094), hrcU (Xoo0091), hrpB1 (Xoo0090), hrcV (Xoo0092), and hrpF (Xoo0109), in the ΔXoo0310 mutant cultured in hrp-inducing XOM2 broth was 17- to 60-fold higher than that in the wild type, and the expression of these hrp genes in the CΔXoo0310 complemented mutant restored the lower wild-type level (Fig. 5). The enhanced pathogenicity on rice in the ΔXoo0310 mutant was suggested to be at least partly due to the hyperexpression of hrp genes.

Fig. 5.

RT-PCR analyses of hrp genes. Expression of hrpG, hrpX, hrpE, hrcQ, hrcU, hrpB1, hrcV, and hrpF genes of the WT, ΔXoo0310 mutant, and CΔXoo0310 complemented strains cultured in XOM2 (hrp-inducing) broth. Values relative to the mean expression for the WT were calculated using the ΔΔCT method (see Materials and Methods). *, significant at the 5% level in a one-sample t test. Error bars indicate standard deviations (±) for data from three independent experiments.

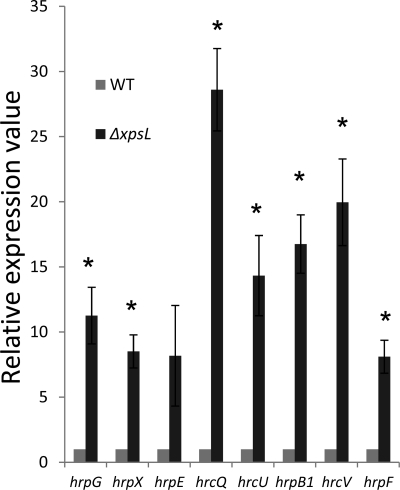

XpsL regulates expression of hrp genes.

When the expression of hrpG, hrpX, hrpE, hrcQ, hrcU, hrpB1, hrcV, and hrpF was compared between the WT and ΔxpsL strains in hrp-inducing XOM2 broth (Fig. 6), the expression of these hrp genes, including hrp regulatory genes in the ΔxpsL mutant, was 8- to 28-fold higher than that of the wild type. Thus, xpsL was also shown to repress the expression of hrp genes by repressing that of hrp regulatory genes. However, since the xpsL mutant showed almost no pathogenicity, the secretion of the extracellular enzymes was shown to be the major requirement for the pathogenicity of X. oryzae pv. oryzae. It was rather unexpected that both kdgR and xpsL of X. oryzae pv. oryzae were found to repress the expression of hrp regulatory genes, which should result in the repression of the genes in hrp regulons.

Fig. 6.

RT-PCR analyses of hrp genes. Expression of hrpG, hrpX, hrpE, hrcQ, hrcU, hrpB1, hrcV, and hrpF genes of WT and ΔxpsL strains cultured in XOM2 (hrp-inducing) broth. Values relative to the mean expression in the WT were calculated using the ΔΔCT method (see Materials and Methods). *, significant at the 5% level in a one-sample t test. Error bars indicate standard deviations (±) for data from three independent experiments.

The KdgR box in promoter regions of hrpG and hrpX genes.

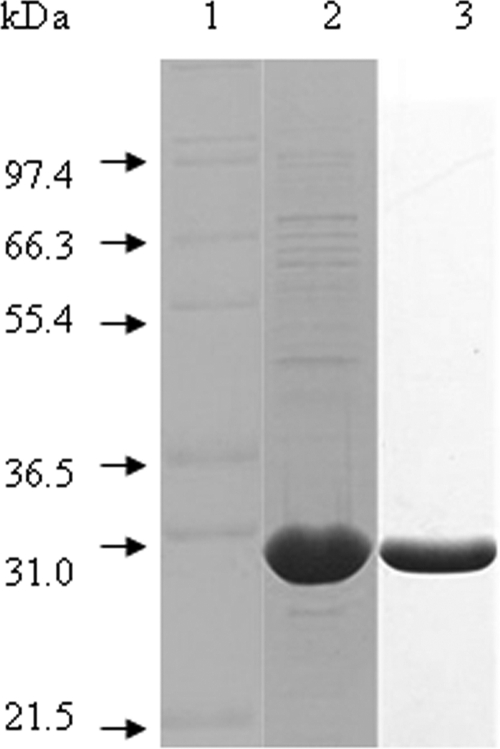

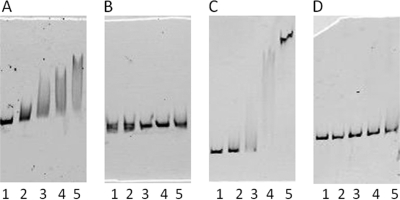

From a database search of X. oryzae pv. oryzae MAFF311018, putative KdgR binding sites were found in base pairs 260 to 245 upstream from the translational start site in the promoter region of hrpG (GTAAGAGCTCCGTTAC) and in base pairs 90 to 75 upstream from the translational start site in the promoter region of hrpX (ACAAATTCCATTGGAT) in X. oryzae pv. oryzae. Putative KdgRxoo (Fig. 7) and putative KdgRxac (not shown) were overexpressed and purified as described in Materials and Methods. By EMSA, KdgRxoo bound to the hrpG and hrpX promoter regions of X. oryzae pv. oryzae (Fig. 8A and 9A), but it failed to bind to hrpG promoter regions with the 60-bp deletion and to hrpX promoter regions with the 50-bp deletion (Fig. 8B and 9B). Since these deleted promoters contained the 15-bp KdgR binding box, KdgRxoo may bind to the promoter regions of hrpG and hrpX specifically at KdgR binding site in X. oryzae pv. oryzae. Furthermore, KdgRxac was shown to bind to X. axonopodis pv. citri promoters (Fig. 8C and 9C), but KdgRxoo did not bind to them (Fig. 8D and 9D), while it bound to X. oryzae pv. oryzae promoters (Fig. 8A and 9A). These data suggest that KdgRxoo may bind at least to the hrpG and hrpX promoters in a species-specific manner.

Fig. 7.

SDS-PAGE analysis of overexpressed His6-KdgRxoo. E. coli BL21(DE3) carrying pETkdgR was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG into the medium and purified as described in Materials and Methods. The crude extract (lane 2) and His6 column-purified protein (lane 3) were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE. Molecular mass standards were loaded in lane 1.

Fig. 8.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. (A and B) Target DNA, X. oryzae pv. oryzae hrpG promoter region (A) or X. oryzae pv. oryzae hrpG kdgR box deletion promoter region (B), was mixed with purified His-KdgRxoo protein. (C and D) Target DNA, X. axonopodis pv. citri hrpG promoter region (C) or X. oryzae pv. oryzae hrpG promoter region (D), was mixed with purified His-KdgRxac protein. The probe labeled with rhodamine dye (20 ng) was incubated in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lanes 2 to 5) of increasing amounts of the KdgR protein (50, 150, 300, and 500 nM).

Fig. 9.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Target DNA, X. oryzae pv. oryzae hrpX promoter region (A) or X. oryzae pv. oryzae hrpX kdgR box deletion promoter region (B), was mixed with purified His-KdgRxoo protein. Target DNA, X. axonopodis pv. citri hrpX promoter region (C) or X. oryzae pv. oryzae hrpX promoter region (D), was mixed with purified His-KdgRxac protein. The probe labeled with rhodamine dye (20 ng) was incubated in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lanes 2 to 5) of increasing amounts of the KdgR protein (50, 150, 300, and 500 nM).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that a kdgR ortholog mutant in X. oryzae pv. oryzae MAFF311018 caused increased pathogenicity on rice. The enhancements were not due to the derepression of extracellular enzymes such as amylase, cellulase, xylanase, and protease but were due to the derepression of hrp genes.

KdgR was originally identified in D. dadantii as a negative regulator for the genes involved in degradation of pectic acid and their metabolism (40). Later it was shown to be a universal negative regulator of pectate lyase genes in plant-pathogenic enterobateria, including D. dadantii, E. amylovora, and P. carotovorum (27, 28, 37, 43). The mechanism by which KdgR acts as the negative regulator is direct binding to the promoter regions of pel and their related genes (37). Thus, the kdgR-deficient mutant showed derepression (namely, induction) of pel and related genes that led to severe soft rotting (2, 27, 40, 43).

The KdgR ortholog was annotated in another important genus of phytopathogenic bacteria, Xanthomonas spp., in X. oryzae pv. oryzae and X. axonopodis pv. citri, as ORF Xoo3010 (http://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?xom:XOO_0310) and ORF Xac4191 (http://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?xac:XAC4191), respectively. However, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene database indicated no orthologs of pectate lyase or of polygalacturonase genes for X. oryzae pv. oryzae, while three orthologs were annotated for X. axonopodis pv. citri. No activities of the pectate lyase or of polygalacturonase were confirmed to be detected in X. oryzae pv. oryzae. The absence of the pel and peh genes in X. oryzae pv. oryzae may be due to the following facts: X. oryzae pv. oryzae infects only rice plants, of which the cell walls contain a large amount of xylan but only a few pectic substances (58).

HrpG and HrpX were reported to be the major regulatory proteins for the control of hrp regulon gene expression and were shown to be responsible for the type III secretion system and for the pathogenicity and HR elicitation in many Xanthomonas spp. (7, 11, 12, 15, 50, 52, 56, 57). It was reported that hrpG itself was shown to be regulated by other regulators. Recently, we reported a new pathogenicity-related gene (Xoo1662) encoding a leucine-rich protein, LrpX, which is involved in negative regulation of hrpG and most hrp operon genes in X. oryzae pv. oryzae (17, 18). A novel regulatory gene, trh, was identified as a positive regulator of HrpG both under in vitro hrp-inducing conditions and in planta (52). Also, HrpX was reported to be regulated by the expression of some other effectors. Sixteen novel type III secretion effectors were identified in X. oryzae pv. oryzae, and their expression was shown to be regulated by HrpX (9). Here we showed that KdgRxoo regulates negatively the expression of hrp regulatory genes and hrp genes. When the repression of hrp genes by KdgR failed, the pathogenicity of the kdgR mutant was enhanced. Our report may show for the first time that KdgRxoo represses pathogenicity at least partly by repressing hrp genes but not extracellular enzyme genes, such as pectate lyases, unlike the case with D. dadantii and P. carotovorum (28, 40, 43).

XOM2 medium was reported to be effective for detecting the induction of hrp genes of X. oryzae pv. oryzae both in vitro and in planta (9). In this work, we grew X. oryzae pv. oryzae mutant strains in XOM2 medium, and the quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showed higher virulence for the ΔXoo0310 mutant than for the wild type. This enhanced virulence of the mutant strain may be due to the hyperexpression of hrp genes.

The putative KdgR binding boxes were found in the promoter regions of hrpG and hrpX genes of both X. oryzae pv. oryzae and X. axonopodis pv. citri on the basis of similarity to the KdgR binding box (5′-G/AA/TA/TGAAA[N6]TTTCAG/TG/TA-3′) reported in E. chrysanthemi (33, 41, 42). EMSA showed clear binding of the KdgRxoo protein to the X. oryzae pv. oryzae promoter fragments but no binding of the KdgRxac protein to X. oryzae pv. oryzae promoter fragments (Fig. 8A and D and 9A and D). Thus, there was clear specificity in terms of the binding of KdgR to the same promoters from different bacterial strains. The amino acid sequence alignments of KdgRxoo and KdgRxac showed an 18% difference in amino acids; these portions may function as the binding domain(s) for its corresponding promoters.

In this study, we also demonstrated that a mutant deficient in a functional xpsL gene in X. oryzae pv. oryzae showed dramatically decreased pathogenicity on rice. It was known that xpsL is responsible for the secretion of cellulase and xylanase in X. oryzae pv. oryzae (10). We confirmed that xpsL is responsible for the secretion of protease, in addition to these enzymes, in X. oryzae pv. oryzae. An xpsF mutant and an xpsD mutant of X. oryzae pv. oryzae showed a loss of virulence, with the secretion of xylanase affected (39). The xpsE gene, which is required for T2SS, was also shown to be required for the secretion of xylanase and cellulase and full virulence in X. oryzae pv. oryzae (49). Here we confirmed that xpsL equally resulted in the loss of virulence, and the secretion of extracellular enzymes is mandatory for virulence (Fig. 4). In the qRT-PCR test, the ΔxpsL strain showed higher expression of hrp genes than the wild type in XOM2 broth (Fig. 6). The mechanism, however, is totally unknown at present and remains to be elucidated. Considering that XpsL, which is a component of the T2SS, is located in the inner membrane, it may be indirectly involved in the induction of hrp genes.

In this study, the hypersensitive response (HR) of wild-type and mutant strains of X. oryzae pv. oryzae was also studied. When the suspensions of the WT, the ΔXoo0310 mutant, the CΔXoo0310 complementary mutant, and the ΔxpsL strain were infiltrated into the intracellular area of tobacco leaves, they all elicited HR to the same extent (data not shown) in spite of the fact that kdgR and xpsL were shown to repress the expression of hrp genes (Fig. 5 and 6). Thus, we believe that the requirements of a hyperinduced level for full virulence are not so stringent for the elicitation of the HR.

Recently, HrpG and HrpX of X. axonopodis pv. citri were suggested to be involved in the global signaling network, since they were shown to regulate the genes for type II secretion machinery, together with many unknown genes in addition to those for T3SS machinery and effectors (3, 13, 19, 60). Our current finding that KdgR in X. oryzae pv. oryzae regulates the expression of hrp genes at the transcriptional level and specific binding of KdgR to the promoter regions of hrpG and hrpX indicated that KdgR may indirectly regulate many genes and function as a global regulator by regulating hrpG and hrpX, which were known as global regulators. Furthermore, KdgR was reported to be the universal negative regulator of the genes of type II extracellular secretion enzymes by directly binding to their promoter regions (27, 28, 37, 43). Thus, KdgR may be involved in global regulation in many ways in addition to regulation of extracellular enzymes and via hrpG and hrpX.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Tsuge, H. Kaku, and A. Furutani for the gift of the X. oryzae pv. oryzae ΔxpsL mutant.

This research was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid (no. 17108001) and by a grant for Promotion in Science (no. 13073) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. Y. Lu is grateful for a fellowship supported by the Chinese government.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ausubel F. M., et al. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beatrice P., Loiseau L., Barras F. 2001. An inner membrane platform in the type II secretion machinery of gram-negative bacteria. EMBO Rep. 2:244–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brencic A., Winans S. C. 2005. Detection of and response to signals involved in host-microbe interactions by plant-associated bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:155–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brinkrolf K., Brune I., Tauch A. 2006. Transcriptional regulation of catabolic pathways for aromatic compounds in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Genet. Mol. Res. 5(4):773–789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chatterjee S., Sankaranarayanan R., Sonti R. V. 2003. PhyA, a secreted protein of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, is required for optimum virulence and growth on phytic acid as a sole phosphate source. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16:973–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cianciotto N. P. 2005. Type II secretion: a protein secretion system for all seasons. Trends Microbiol. 13:581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferluga S., Venturi V. 2009. OryR is a LuxR-family protein involved in interkingdom signaling between pathogenic Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and rice. J. Bacteriol. 191:890–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Filloux A., Hachani A., Bleves S. 2008. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology 154:1570–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furutani A., et al. 2009. Identification of novel type III secretion effectors in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22:96–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Furutani A., Tsuge S., Kubo Y. 2004. Evidence for HrpXo-dependent expression of type II secretory proteins in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J. Bacteriol. 186:1374–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Furutani A., et al. 2006. Identification of novel HrpXo regulons preceded by two cis-acting elements, a plant-inducible promoter box and a 10 box-like sequence, from the genome database of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 259:133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghosh P. 2004. Process of protein transport by the type III secretion system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:771–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo Y., Figueiredo F., Jones J., Wang N. 2011. HrpG and HrpX Play global roles in coordinating different virulence traits of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24:649–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horton R. M., Cai Z. L., Ho S. N., Pease L. R. 1990. Gene splicing by overlap extension: tailor-made genes using the polymerase chain reaction. Biotechniques 8:528–535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hu J., Qian W., He C. Z. 2007. The Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae eglXoB endoglucanase gene is required for virulence to rice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 269:273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reference deleted.

- 17. Islam M. R., Kabir M. S., Hirata H., Tsuge S., Tsuyumu S. 2008. A leucine-rich protein, LrpX, is a new regulator of hrp genes in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. doi:10.1007/s10327-008-0124-2 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Islam M. R., Hirata H., Tsuge S., Tsuyumu S. 2008. Self-regulation of a new pathogenicity-related gene encoding leucine-rich protein LrpX in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. doi:10.1007/s10327-008-0123-3 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jha G., Rajeshwari R., Sonti R. V. 2007. Functional interplay between two Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae secretion systems in modulating virulence on rice. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson T. L., Abendroth J., Hol W. G. J., Sandkvist M. 2006. Type II secretion: from structure to function. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 255:175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kauffman H. E., Reddy A. P. K., Hsieh S. P. V., Marca S. D. 1973. An improved technique for evaluation of resistance of rice varieties to Xanthomonas oryzae. Plant Dis. Rep. 57:537–541 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krell T., Molina-Henares A. J., Ramos J. L. 2006. The IclR family of transcriptional activators and repressors can be defined by a single profile. Protein Sci. 15:1207–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lautier T., Blot N., Muskhelishvili G., Nasser W. 2007. Integration of two essential virulence modulating signals at the Erwinia chrysanthemi pel gene promoters: a role for Fis in the growth-phase regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 66(6):1491–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee B. M., et al. 2005. The genome sequence of Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar oryzae KACC10331, the bacterial blight pathogen of rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:577–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lefebvre B., Formstecher P., Lefebvre P. 1995. Improvement of the gene splicing overlap (SOE) method. Biotechniques 19:186–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Y.-R., et al. 8 April 2011. Hpa2 is required by HrpF to translocate Xanthomonas oryzae TAL effectors into rice for pathogenicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. doi:10.1128/AEM.02849-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liao C.-H. 1991. Cloning of pectate lyase gene pel from Pseudomonas fluorescens and detection of sequences homologous to pel in Pseudomonas viridiflava and Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 173:4386–4393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu Y., et al. 1999. kdgREcc negatively regulates genes for pectinases, cellulase, protease, HarpinEcc, and a global RNA regulator in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. J. Bacteriol. 181:2411–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matsumoto H., Muroi H., Umehara M., Yoshitake Y., Tsuyumu S. 2003. Peh production, flagellum synthesis, and virulence reduced in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora by mutation in a homologue of cytR. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16:389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mew T. W., Alvarez A. M., Leach J. E., Swings J. 1993. Focus on bacterial blight of rice. Plant Dis. 77:5–12 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mortensen B. L., et al. 2010. Effects of the putative transcriptional regulator IclR on Francisella tularensis pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 78:5022–5032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nasser W., Reverchon S., Condemine G., Robert-Baudouy J. 1994. Specific interactions of Erwinia chrysanthemi KdgR repressor with different operators of genes involved in pectinolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 236(2):427–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nomura K., Nasser W., Kawagishi H., Tsuyumu S. 1998. The pir gene of Erwinia chrysanthemi EC16 regulates hyperinduction of pectate lyase virulence genes in response to plant signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95(24):14034–14039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ochiai H., Inoue Y., Takeya M., Sasaki A., Kaku H. 2005. Genome sequence of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae suggests contribution of large numbers of effector genes and insertion sequences to its race diversity. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 39:275–287 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reference deleted.

- 37. Pissavin C. J., Baudouy R., Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat N. 1996. Regulation of pelZ, a gene of the pelB-pelC cluster encoding a new pectate lyase of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937. J. Bacteriol. 178:7187–7196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quandt J., Hynes M. F. 1993. Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 127:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ray S. K., Rajeshwari R., Sonti R. V. 2000. Mutants of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae deficient in general secretory pathway are virulence deficient and unable to secrete xylanase. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13:394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reverchon S., Robert-Baudouy J. 1987. Regulation of expression of pectate lyase genes pelA, pelD, and pelE in Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Bacteriol. 169:2417–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reverchon S., Nasser W., Robert-Baudouy J. 1991. Characterization of kdgR, a gene of Erwinia chrysanthemi that regulates pectin degradation. Mol. Microbiol. 5(9):2203–2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rodionov D. A., Gelfand M. S., Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat N. 2004. Comparative genomics of the KdgR regulon in Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937 and other gamma-proteobacteria. Microbiology 150:3571–3590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rouanet C., Nomura K., Tsuyumu S., Nasser W. 1999. Regulation of pelD and pelE, encoding major alkaline pectate lyases in Erwinia chrysanthemi: involvement of the main transcriptional factors. J. Bacteriol. 181:5948–5957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Salzberg S. L., et al. 2008. Genome sequence and rapid evolution of the rice pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae PXO99A. BMC Genomics 9:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sarkar D., Siddiquee K. A., Araúzo-Bravo M. J., Oba T., Shimizu K. 2008. Effect of cra gene knockout together with edd and iclR genes knockout on the metabolism in Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 190(5):559–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shen Y., Ronald P. 2002. Molecular determinants of disease and resistance in interactions of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and rice. Microbes Infect. 4:1361–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shevckik V. E., Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat N. 2003. PaeX, a second pectin acetylesterase of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937. J. Bacteriol. 185:3091–3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sun Q. H., et al. 2005. Type-II secretion pathway structural gene xpsE, xylanase- and cellulase secretion and virulence in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Plant Pathol. 54:15–21 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tang X. Y., Xiao Y. M., Zhou J. M. 2006. Regulation of the type III secretion system in phytopathogenic bacteria. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 19:1159–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thomson N. R., Nasser W., McGowan S., Sebaihia M., Salmond G. P. C. 1999. Erwinia carotovora has two KdgR-like proteins belonging to the IclR family of transcriptional regulators: identification and characterization of the RexZ activator and the KdgR repressor of pathogenesis. Microbiology 145:1531–1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsuge S., Furutani A., Kaku H. 2006. Gene involved in transcriptional activation of the hrp regulatory gene hrpG in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J. Bacteriol. 188:4158–4162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tsuge S., Furutani. A., Kubo Y. 2002. Expression of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae hrp genes in XOM2, a novel synthetic medium. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 68:363–371 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reference deleted.

- 55. Watabe M., Yamaguchi M., Kitamura S., Horino O. 1993. Immunohistochemical studies on the extracellular polysaccharide produced by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in infected rice leaves. Can. J. Microbiol. 39:1120–1126 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wei K., Tang J. L. 2007. hpaR, a putative marR family transcriptional regulator, is positively controlled by HrpG and HrpX and involved in the pathogenesis, hypersensitive response, and extracellular protease production of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. J. Bacteriol. 189:2055–2062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wengelnik K., Bonas U. 1996. HrpXv, an AraC-type regulator, activates expression of five of the six loci in the hrp cluster of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 178:3462–3469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yamaguchi T., Kuroda M., Shibuya N. 2009. Suppression of a phospholipase D gene, OsPLDb1, activates defense responses and increases disease resistance in rice. Plant Physiol. 150:308–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yamamoto K., Ishihama A. 2003. Two different modes of transcription repression of the Escherichia coli acetate operon by IclR. Mol. Microbiol. 47:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yamazaki A., Hirata H., Tsuyumu S. 2008. Type III regulators HrpG and HrpXct control synthesis of α-amylase, which is involved in in planta multiplication of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 74:254–257 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang H. B., Wang L. H., Zhang L. H. 2002. Genetic control of quorum-sensing signal turnover in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99(7):4638–4643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]