Abstract

Hypoxia contributes to the pathogenesis of various human diseases, including pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH), stroke, myocardial or cerebral infarction, and cancer. For example, acute hypoxia causes selective pulmonary artery (PA) constriction and elevation of pulmonary artery pressure. Chronic hypoxia induces structural and functional changes to the pulmonary vasculature, which resembles the phenotype of human PAH and is commonly used as an animal model of this disease. The mechanisms that lead to hypoxia-induced phenotypic changes have not been fully elucidated. Here, we show that hypoxia increases type I collagen prolyl-4-hydroxylase [C-P4H(I)], which leads to prolyl-hydroxylation and accumulation of Argonaute2 (Ago2), a critical component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Hydroxylation of Ago2 is required for the association of Ago2 with heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90), which is necessary for the loading of microRNAs (miRNAs) into the RISC, and translocation to stress granules (SGs). We demonstrate that hydroxylation of Ago2 increases the level of miRNAs and increases the endonuclease activity of Ago2. In summary, this study identifies hypoxia as a mediator of the miRNA-dependent gene silencing pathway through posttranslational modification of Ago2, which might be responsible for cell survival or pathological responses under low oxygen stress.

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) is a disease characterized by pulmonary vascular remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy (43). Hypoxia is considered a major factor in the pathogenesis of PAH (43) as well as tumor growth (17). Acute hypoxia causes selective pulmonary artery (PA) constriction and an increase in pulmonary artery pressure. Exposure to chronic hypoxia induces structural and functional changes to the pulmonary vasculature, which resembles that of human PAH and is commonly used as an animal model of this disease (43). Chronic hypoxia treatment in animals induces pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) to undergo dedifferentiation; the cells become less contractile and more proliferative and display increased motility (2). This phenotype switch is believed to be the underlying cause of hypoxia-induced vascular remodeling, characterized by thickening of the vascular smooth muscle cell (vSMC) layer and elevation of PA resistance (37). Various growth factor signaling pathways, including transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs), regulate the vSMC phenotypic switch to maintain PASMC homeostasis as well as promote repair following vascular injury (37). These growth factors modulate the vSMC phenotype through direct alterations in protein-coding gene expression as well as through modulation of the levels of small regulatory RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), which subsequently regulate the expression of a number of protein-coding genes (3, 9, 10).

Recent studies indicate a critical role of miRNAs in the hypoxia response in oxygen-deprived neoplastic tumors and pulmonary tissues (25). Hypoxia causes a change in gene expression through a transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), which orchestrates the transcriptional regulation of a variety of genes, including genes encoding miRNAs, such as miR-210 or miR-181b (25). However, an HIF-1-independent effect of hypoxia on miRNA expression or its effect on proteins required for miRNA biogenesis/function, such as Argonaute (Ago) proteins, has not been investigated. To elucidate the molecular basis for hypoxia-mediated vascular remodeling and the pathogenesis of PAH, it is critical to uncover the mechanism of hypoxia-induced regulation of miRNA levels and function.

miRNAs play a critical role in a wide range of physiological and pathological cellular processes (6–8, 11, 31). The important function of miRNAs is particularly evident when cells are exposed to stress, such as hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, oxidation, or DNA damage (24, 46). Small RNAs, such as miRNAs and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), guide a ribonucleoprotein complex known as the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), containing a member of the conserved Ago protein family, to sites predominantly in the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of their target mRNAs, resulting in the destabilization of the mRNAs and/or inhibition of translation (24, 46). In humans, there are four members of the Ago protein subfamily, Ago1 to -4. Only Ago2 is known to exhibit endonuclease activity (12). Ago1 to -4 are ubiquitously expressed and associate with both miRNAs and siRNAs (12). It has been elucidated that the ATP hydrolysis activity of the Hsc70/Hsp90 chaperone machinery is required for the loading of small RNA duplexes (siRNA and miRNA) into RISC (21). Small RNA duplexes then guide Ago proteins to their target mRNAs (12). Perfect complementarity between the small RNA sequence and the target sequence promotes Ago2-mediated endonuclease activity, whereas mismatches in the binding region of the miRNA lead to repression of gene expression at the level of translation or mRNA stability (12). More recently, it was demonstrated that the Dicer-independent cleavage of precursor miR-451 (pre-miR-451) to generate mature miR-451 requires Ago2, indicating a novel role of Ago2 in the second processing step of miRNA biogenesis (4, 51). However, the mechanism of action and the mechanism of regulation of Ago proteins are poorly understood.

It has been demonstrated that Ago proteins are posttranslationally modified and regulated at the level of protein stability and silencing function in mammals (12). Ago proteins associate with both the α and β subunits of type I collagen prolyl-4-hydroxylase [C-P4H(I); EC 1.14.11.2] and can be hydroxylated, which results in increased Ago stability and activity (42). In HeLa S3 cells, high levels of hydroxylation are observed in Ago2 at proline (Pro) 700 (42). However, it is unclear whether Ago2 hydroxylation is regulated by physiological stimuli and whether hydroxylation affects Ago2 function. C-P4H(I) was originally identified as a critical regulator of collagen synthesis. Hydroxylation of collagen by C-P4H(I) is essential for the formation of triple-helical collagen and is a rate-limiting step in collagen synthesis (34). Inactivation of C-P4H(I) leads to the formation of hypohydroxylated collagen, which is unstable, and leads to the classical symptoms of scurvy (34). Because collagen constitutes the major extracellular matrix protein, the quantity and activity of C-P4H(I) are tightly regulated (34). Posttranscriptional regulation of C-P4Hα(I) at the level of mRNA stability (13) and translational control (14) has been demonstrated to be a key regulatory mechanism of collagen synthesis in fibrosarcoma. Induction of collagen upon activation of the TGFβ signaling pathway is also associated with the induction of C-P4H(I) (50).

In this study, we demonstrate that hypoxia increases C-P4H(I) expression and induces accumulation of Ago2 through C-P4H(I)-mediated prolyl-hydroxylation at Pro700. We demonstrate that hypoxia-induced prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 by C-P4H(I) promotes the association of Ago2 with Hsp90, leads to the translocation of Ago2 to stress granules (SGs), and increases miRNA levels. A hydroxylation-resistant mutant of Ago2 fails to associate with Hsp90, translocate to stress granules, or increase the levels of miRNAs. Thus, we propose that hypoxia-induced posttranslational modification of Ago2 affects protein stability and subcellular localization and results in increased levels of miRNAs and enhanced silencing of target mRNAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human primary pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) were purchased from Lonza (number CC-2581) and maintained in smooth muscle growth medium-2 (Sm-GM2) (Lonza) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma). U2OS and U2OS stable cell lines expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-let-7 sensor construct, described previously (42), were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma). Cells were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2.

Animal study and immunohistochemistry.

All experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tufts Medical Center. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized to 17 days of normoxia or hypobaric hypoxia as described previously (41). At the end of the exposure period, rats were sacrificed and the lungs were processed for paraffin embedding. Portions (5 μm) of paraffin-embedded tissue sections were immunostained as described previously (3).

Normoxia/hypoxia treatment.

Hypoxic conditions were generated by first replacing culture media with fresh media equilibrated with a hypoxic gas mixture and then incubating cells in a sealed modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg) after flushing with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% N2 for 5 min. Normoxic controls were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2.

Plasmid DNA transfection and expression constructs.

Cells were transfected using linear polyethylenimine (PEI), with a molecular weight (MW) of 25,000 (Polysciences, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Amino-terminal Flag-tagged Ago1, Ago2, mutant Ago2 (Pro700A), and Ago3 were reported previously (42). The miR-144/451 expression construct was described previously (51).

RNA interference.

Synthetic small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting human Ago2 or C-P4Hα(I) were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Silencer Select Pre-designed) and transfected into cells by using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. An siRNA with a nontargeting sequence (Negative Control siRNA, Qiagen) was used as a negative control.

The following primers were used: for Ago2, 5′-GGUCUAAAGGUGGAGAUAATT-3′ and 5′-UUAUCUCCACCUUUAGACCTT-3′; for C-P4Hα(I), 5′-CUAGUACAGCGACAAAAGATT-3′ and 5′-UCUUUUGUCGCUGUACUAGTT-3′.

Antibodies and chemical inhibitors.

Antibodies used in this study include anti-Ago1 (04-083; Millipore), anti-Ago2 (015-22031; Wako Chemicals), anti-Ago3 (SAB4200112; Sigma), anti-Ago4 (05-967; Millipore), anti-Drosha (A301-886A; Bethyl), anti-Dicer (ab14601; Abcam), anti-C-P4Hα(I) (PAB7221; Abnova), anti-C-P4Hβ (sc-20132; Santa Cruz), anti-Flag epitope tag (M2; Sigma), anti-Hsp90 (MAB3286; R&D Systems), anti-TIA-1 (sc-1751; Santa Cruz), and anti-β-actin (A5441; Sigma). The secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence staining were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory Inc. Arsenite (S-7400) and geldanamycin (GA; G3381) were purchased from Sigma. Concentrations of geldanamycin were optimized in each cell type to achieve maximal Hsp90 inhibition while minimizing cellular toxicity: 1 μM in U2OS cells and 0.1 μM in PASMCs.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot assays.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot assays were performed as described previously (9). Protein bands were quantitated by densitometry using ImageJ gel analysis software (rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

RNA preparation and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR).

Total RNA was extracted from cells by TRIzol (Invitrogen). For detection of mRNAs, 1 μg of RNA was subjected to RT reaction using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantitative analysis of the change in expression levels was calculated by a real-time-PCR machine (iQ5; Bio-Rad). PCR cycle conditions were 94°C for 3 min and 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 40 s. For detection of mature miRNAs, the TaqMan microRNA assay kit (Applied Biosystems) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data analysis was performed by using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method in Bio-Rad software. The average of results of three experiments, each performed in triplicate with standard errors, is presented.

The sequences of RT-PCR primers were as follows: human Ago1, 5′-GGGAAACAGTTCTACAATGG-3′ and 5′-CCCTGAGTAGGTGTTCTTGA-3′; human Ago2, 5′-ATGTTTACAAGTCGGACAGG-3′ and 5′-TCATCTTTGACCATGATTCC-3′; human Ago3, 5′-GGAACAATGAGACGGAAATA-3′ and 5′-CTTCTAGTGGCAGGTAGGTG-3′; human Ago4, 5′-ATGTGGGCCTACAGCTAATA-3′ and 5′-TATCTTCAGGCAAAGATTGG-3′; human C-P4Hα(I), 5′-AAGGCGAGATTTCTACCATA-3′ and 5′-TTGGTCATCTGAAGCAGACT-3′; human C-P4Hβ, 5′-CATACCATTTGGGATCACTT-3′ and 5′-GTCTTGATTTCACCTCCAAA-3′; human Hsp70, 5′-CGGTCCGGATAACGGCTAGCCTGA-3′ and 5′-GTTGGAACACCCCCACGCAGG-3′; human PDCD4, 5′-ATTAATCTGGATGTCCCACA-3′ and 5′-TAAGACGACCTCCATCTCC-3′; human DOCK7, 5′-GCAGAACGGTGGCAGCCGAA-3′ and 5′-TCGGTAAGGGGCACTGTGGTGT-3′; human Sprouty2, 5′-TACAGGTGTGAGGACTGTGG-3′ and 5′-AAGAGACCTTTCACACAGCA-3′; human c-kit, 5′-CACCGAAGGAGGCACTTACAC-3′ and 5′-GGAATCCTGCTGCCACACA-3′; GFP-let-7, 5′-GAACGGCATCAAGGTGAACTT-3′ and 5′-GACGACCTCGAGTGAGGTAGTAGGTTGTATA-3′; human primary miR-21 transcript (pri-miR-21), 5′-TTTTGTTTTGCTTGGGAGGA-3′ and 5′-AGCAGACAGTCAGGCAGGAT-3′; human pri-miR-24-1, 5′-GCGGTGAACTCTCTCTTGTA-3′ and 5′-TTACAGACACGAAGGCTTTT-3′; human pri-miR-222, 5′-ACATTATCAGCTGGGGCTTG-3′ and 5′-ATGGATGGGTGGATGGATAA-3′; human pri-miR-210, 5′-GACCCACTGTGCGTGTGAC-3′ and 5′-CGAATGATTTCGCTTACCC-3′; human pri-miR-23a, 5′-TTTGCTTCCTGTCACAAATC-3′ and 5′-GGAACTTAGCCACTGTGAAC-3′.

Immunofluorescence staining, fluorescence imaging, and image analysis.

PASMCs or U2OS cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline solution and permeabilized using methanol. Cells were then incubated for at least 1 h at room temperature sequentially with primary and secondary antibodies. After washing, cells were mounted on microscope slides using VECTASHIELD mounting medium with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Vector Laboratories). Images were taken on a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope with a CF160 infinity optical system and a Hamamatsu C4742-95 digital camera. Images were quantitated using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Intensity profiles generated using the ImageJ Color Profiler plug-in were used to determine colocalization between Ago2 and stress granules.

Statistical analysis.

The results presented are average results of at least three experiments each performed in triplicate with standard errors. Statistical analyses were performed by analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test or by Student's t test as appropriate, using Prism 4 (GraphPAD Software Inc.). P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Hypoxia increases Ago2.

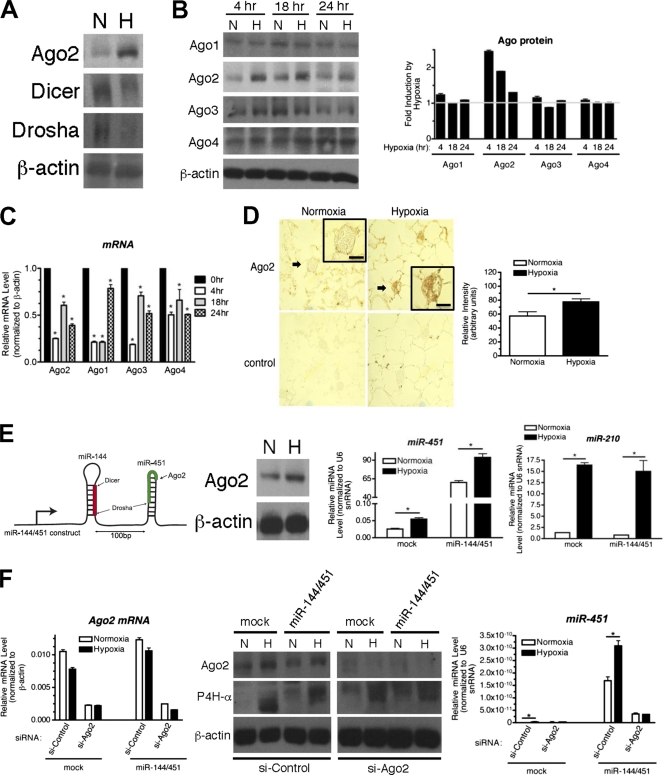

To examine a potential effect of hypoxia on the protein expression of components of the miRNA biogenesis pathway, the miRNA processing enzymes (Dicer and Drosha) and Ago2 protein were examined by immunoblot analysis in PASMCs treated with normoxia or hypoxia (95% N2, 5% CO2) for 24 h. The Ago2 level was significantly increased, while Dicer and Drosha were reduced by hypoxia (Fig. 1 A). Next, we examined other members of the Ago protein family (Ago1 to -4) after hypoxia treatment in PASMCs. Only Ago2 was significantly increased as early as 4 h after hypoxia treatment (Fig. 1B). Despite the increase in protein levels (Fig. 1B), mRNAs of Ago2, as well as other Ago family members, were reduced ∼40 to 70% upon hypoxia treatment (Fig. 1C), indicating that the induction of Ago2 is likely to occur through a posttranscriptional mechanism. To examine whether induction of Ago2 can be observed under chronic hypoxia in vivo, lung sections prepared from rats treated with hypoxia for 17 days were stained with anti-Ago2 antibodies. Chronic hypoxia-treated lungs exhibited pulmonary artery remodeling, such as thickening of the medial wall (Fig. 1D). It was confirmed that the Ago2 protein was elevated in pulmonary arteries after hypoxia treatment (Fig. 1D, arrowheads).

Fig. 1.

Hypoxia mediates the posttranscriptional induction of Ago2. (A) Total cell lysates from PASMCs treated with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-Ago2, anti-Dicer, anti-Drosha, or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies. (B) Total cell lysates from PASMCs treated with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 4, 18, or 24 h were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-Ago1 to -4 or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies (left panel). By densitometry, relative amounts of Ago proteins normalized to β-actin were quantitated. Fold induction (hypoxia/normoxia) is presented (right panel). (C) PASMCs were treated with normoxia or hypoxia for 4, 18, or 24 h and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of Ago1 to -4 mRNAs. Relative levels of mRNA expression normalized to β-actin were quantitated. *, P < 0.05. (D) Immunohistochemical examination of lung sections from rats after 17-day hypoxia or normoxia treatment with anti-Ago2 antibodies (brown, ×400). As a control, staining without the primary antibodies was performed. PAs are indicated with arrowheads. The insets in the panel are enlargements of the indicated PAs. Scale bars, 25 μm (left panel). Relative expression of Ago2 in the PAs was quantitated using ImageJ software (right panel). *, P < 0.05. (E) U2OS cells were transfected with vector (mock) or miR-144/451 construct, followed by normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) treatment for 24 h. Schematic of the miR-144/451 construct is shown (left panel); mature miR-144 is highlighted in red, and mature miR-451 is highlighted in green. Levels of miR-451 or miR-210 normalized to U6 snRNA are presented (right panels). *, P < 0.05. Total cell lysates were prepared from U2OS cells treated with N or H for 24 h and were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-Ago2 or β-actin (loading control) antibodies (middle panel). (F) U2OS cells were transfected with control siRNA (si-Control) or siRNA against Ago2 (si-Ago2) and vector (mock) or miR-144/451 construct, followed by normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) treatment for 24 h. Downregulation of Ago2 by siRNA was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis (left panel) and immunoblot analysis (middle panel). The same membrane was blotted with anti-C-P4Hα and anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies. Relative levels of miR-451 normalized to U6 snRNA are presented (right panel). *, P < 0.05.

It is reported that Ago2 exhibits Dicer-like processing activity and cleaves pre-miR-451 to generate mature miR-451 (4, 51). To demonstrate that hypoxia-mediated induction of Ago2 leads to an induction of Ago2 activity, we examined whether hypoxia increases the level of mature miR-451. Human osteosarcoma U2OS cells were transfected with an miR-144/451 expression construct (Fig. 1E, left panel), which encodes pre-miR-144 and pre-miR-451 (51). In U2OS cells, endogenous Ago2 (Fig. 1E, middle panel) and exogenously expressed Ago1 and Ago3 (data not shown) were elevated upon hypoxia. Hypoxia treatment also increased the level of endogenous miR-451 by ∼2-fold (Fig. 1E, mock). When the miR-144/451 construct was transfected, the level of miR-451 under normoxia was >2,000-fold higher than that in the mock-treated cells as a result of the processing of exogenous pre-miR-451 to miR-451 by Ago2 (Fig. 1E, miR-451 and miR-144/451). Hypoxia treatment further increased the levels of miR-451 by ∼1.5-fold similarly to the endogenous miR-451 (Fig. 1E, miR-451). Both the basal level and the hypoxia-induced level of miR-451 were reduced when endogenous Ago2 was downregulated, demonstrating that Ago2 is essential for the maturation of miR-451 from the miR-144/451 construct (Fig. 1F). These results confirm an increase in Ago2 activity as well as an increase in Ago2 protein after hypoxia treatment (Fig. 1E, middle panel). Altogether, these results indicate a rapid posttranscriptional mechanism of induction of Ago2 protein upon hypoxia treatment in both PASMCs and U2OS cells.

Hydroxylation of Ago2 by C-P4H(I) is mediated by hypoxia.

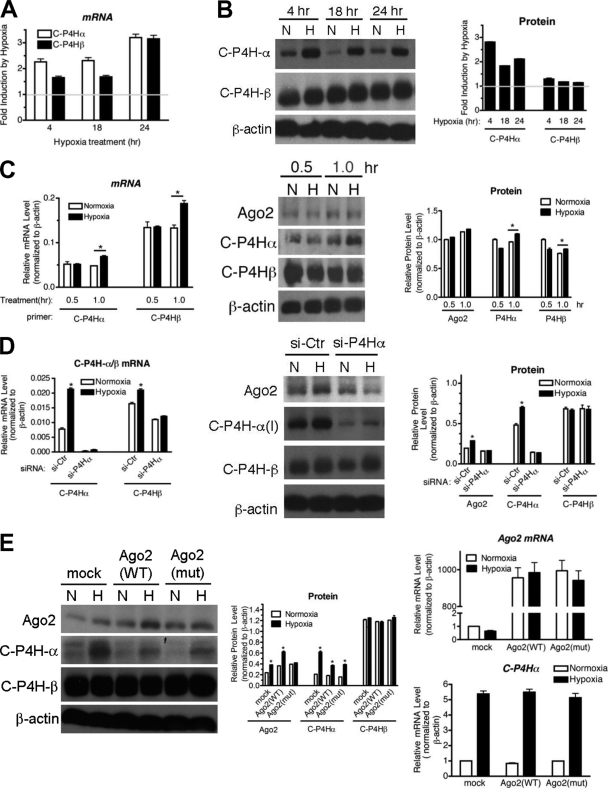

It is reported that Ago2 is prolyl-hydroxylated by C-P4H(I) at Pro700, which inhibits Ago2 degradation and results in the induction of Ago2 (42). As hypoxia-mediated induction of C-P4H(I) has been reported previously (13, 14), we examined whether hypoxia induces C-P4H(I) in PASMCs, which then leads to the accumulation of Ago2. We found that both the mRNA (Fig. 2A) and protein (Fig. 2B) levels of both the α (C-P4Hα) and β (C-P4Hβ) subunits of C-P4H(I) were increased ∼2- to 3-fold by hypoxia. Induction of C-P4Hα/β was observed as early as 1 h after hypoxia treatment and was more rapid than the induction of Ago2 (Fig. 2C), supporting the hypothesis that hydroxylation of Ago2 by C-P4H(I) mediates the induction of Ago2 upon hypoxia.

Fig. 2.

Prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 by C-P4H(I) is critical for the hypoxia-mediated induction of Ago2. (A) PASMCs were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 4, 18, or 24 h and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of C-P4Hα and C-P4Hβ mRNAs. The relative levels of mRNA expression normalized to β-actin were quantitated. Fold induction (hypoxia/normoxia) is presented. (B) Total cell lysates from PASMCs treated with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 4, 18, or 24 h were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-C-P4Hα, anti-C-P4Hβ, or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies (left panel). By densitometry, relative amounts of C-P4H(I) proteins normalized to β-actin were quantitated. Fold induction (hypoxia/normoxia) is presented (right panel). (C) Total cell lysates from PASMCs treated with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 0.5 or 1 h were immunoblotted with anti-Ago2, anti-C-P4Hα, anti-C-P4Hβ, or β-actin (loading control) antibodies (middle panel). By densitometry, relative amounts of Ago2 and C-P4H(I) proteins normalized to β-actin were quantitated (right panel). *, P < 0.05. Levels of C-P4Hα/β mRNAs after N or H treatment (0.5 or 1 h) were quantitated by qRT-PCR normalized to β-actin (left panel). *, P < 0.05. (D) PASMCs were transfected with siRNA against C-P4Hα (si-P4Hα) or nontargeting control (si-Ctr) for 48 h prior to treatment with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-Ago2, anti-C-P4Hα(I), anti-C-P4Hβ, or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies (middle panel). By densitometry, relative amounts of Ago2 and C-P4H(I) proteins normalized to β-actin were quantitated and are presented (right panel). Total RNAs were extracted from the same cells and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. Relative C-P4Hα/β mRNA levels normalized to β-actin are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (left panel). *, P < 0.05. (E) U2OS cells were transfected with vector (mock), wild type (WT) Ago2, or Pro700A mutant (mut) Ago2 cDNA construct followed by treatment with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h. Relative levels of Ago2 or C-P4H(I) proteins normalized to β-actin were examined by immunoblotting (left panel) and quantitated by densitometry (middle panel). Relative mRNA levels of Ago2 (upper right panel) and C-P4Hα (lower right panel) normalized to β-actin are presented as mean ± SD. *, P < 0.05.

To investigate the role of C-P4H(I) in the induction of Ago2 by hypoxia, we used siRNA to knock down C-P4Hα, which is critical for the catalytic activity of C-P4H(I), prior to hypoxia treatment in PASMCs. siRNA downregulated 97% of endogenous C-P4Hα (Fig. 2D). Downregulation of C-P4Hα was associated with a weak reduction of C-P4Hβ (Fig. 2D). Under the condition of C-P4Hα knockdown, accumulation of Ago2 by hypoxia was abolished (Fig. 2D), suggesting an essential role of C-P4H(I) in hypoxia-mediated stabilization of Ago2. The significance of C-P4H(I)-mediated prolyl-hydroxylation was confirmed by examining a mutant of Ago2 [Ago2(mut)], which is mutated at Pro700 to Ala (42). The wild type [Ago2(WT)] or the Ago2 mutant [Ago2(mut)] was transfected into U2OS cells, followed by hypoxia treatment. Exogenous Ago2(WT) or Ago2(mut) showed no effect on the levels of the C-P4Hβ subunit (Fig. 2E). Unlike endogenous Ago2 (Fig. 2E, mock) or exogenously expressed Ago2(WT), Ago2(mut) did not accumulate upon hypoxia (Fig. 2E), supporting a critical role of the C-P4H(I) hydroxylation site in the hypoxia-induced accumulation of Ago2.

Hypoxia induces Ago2 translocation to stress granules.

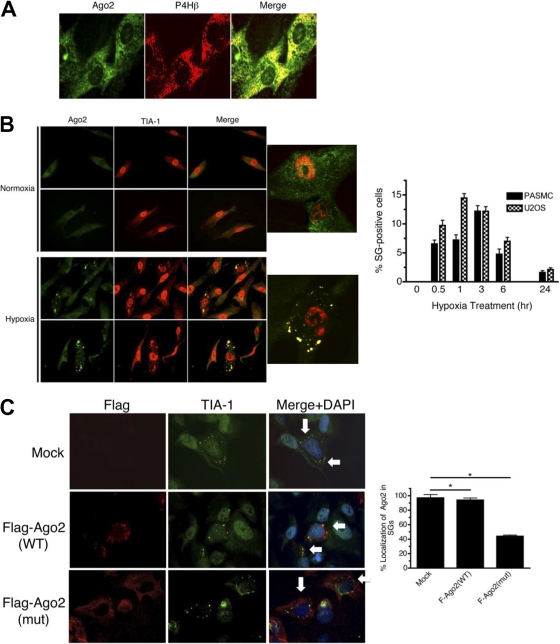

Previous studies suggest that upon various cellular stresses, Ago2 translocates to specific compartments of the cell, including SGs and processing bodies (P-bodies) (28, 38, 42). PASMCs were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against Ago2 or C-P4Hβ (Fig. 3A). As previously reported (42), under normoxia, Ago2 was found to be colocalized with C-P4Hβ in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A and B, Normoxia). Upon hypoxia treatment for 3 h, Ago2 accumulated at foci in the cytoplasm, which coincided with staining for TIA-1, a marker of SGs (42), suggesting hypoxia-induced translocation of Ago2 to SGs (Fig. 3B). No SGs were found in cells under normoxia (Fig. 3A and B). In both PASMCs and U2OS cells, ∼5 to 10% of cells contained SGs at 30 min after hypoxia, with the percentage of SG-positive cells increasing to 10 to 15% after 3 h and then gradually declining by 24 h (Fig. 3B, right panel). Ago2 localized to SGs in more than 97% of SG-positive cells (Fig. 3C, Mock). These results suggest that hypoxia promotes (i) formation of SGs and (ii) translocation of Ago2 to SGs. Interestingly, we observed that translocation of the prolyl-hydroxylation site mutant [Ago(mut)] to SGs after hypoxia treatment was greatly reduced (∼40%) compared with that of the wild-type Ago2 (>97%) (Fig. 3C), suggesting that prolyl-hydroxylation increases SG localization of Ago2 either by facilitating (i) the translocation of Ago2 to SGs or (ii) a stable localization of Ago2 in SGs.

Fig. 3.

Hypoxia induces the translocation of Ago2 to SGs. (A) Subcellular localization of Ago2 was examined by immunofluorescence analysis in PASMCs stained with FITC-Ago2 (green) and rhodamine-P4Hβ subunit (red) under normoxia. (B) PASMCs were treated with normoxia or hypoxia for 3 h and subjected to immunofluorescence staining with FITC-Ago2 antibodies (green) and rhodamine-TIA-1 antibodies (red). The accompanying graph shows quantification of cells containing SGs after treatment with hypoxia for the indicated periods of time. Approximately 200 cells from at least 10 independent fields have been counted for each time point, and SG-positive cells are presented as a percentage of the total population. (C) U2OS cells were transfected with vector (mock), Flag-tagged Ago2(WT), or Flag-tagged Ago2(mut) cDNA construct followed by treatment with hypoxia for 3 h. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using rhodamine-Flag antibodies (red) and FITC-TIA-1 antibodies (green). Arrows indicate the position of TIA-1-positive stress granules. The accompanying graph shows quantification of the percentage of Ago2 localized in SGs for each condition. Mock refers to the localization of endogenous Ago2. Approximately 70 SGs in at least three cells have been examined for each condition. *, P < 0.05.

Hypoxia induces association of Ago2 with Hsp90.

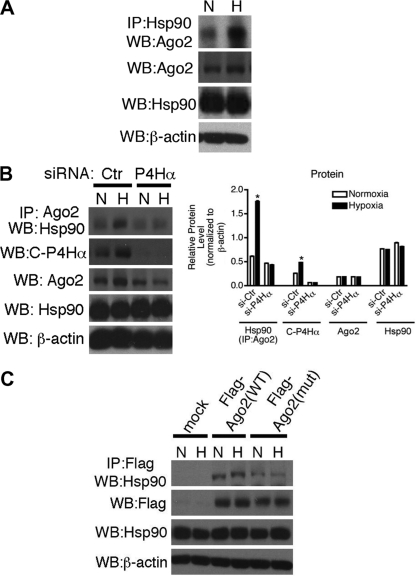

A previous study indicated that the interaction of Ago with the chaperone protein complex, Hsc70/Hsp90, is critical for the loading of siRNA or miRNA into RISC (21). We examined whether hypoxia-induced prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 affects the association of Ago2 with Hsp90. Total cell lysates from PASMCs exposed to normoxia or hypoxia were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Hsp90 antibody, followed by immunoblot analysis with anti-Ago2 antibody (Fig. 4A). Association of endogenous Ago2 with Hsp90 was observed under normoxia; however, the Ago2-Hsp90 interaction was greatly increased after hypoxia (Fig. 4A). Hypoxia-induced interaction between Ago2 and Hsp90 was inhibited when C-P4H(I) activity was downregulated by si-C-P4Hα (Fig. 4B), indicating an importance of prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2. Consistently, association of Hsp90 with the prolyl-hydroxylation site Ago2 mutant [Ago(mut)] was significantly reduced in comparison with Ago2(WT) (Fig. 4C), indicating a critical role of Pro700 hydroxylation of Ago2 by C-P4H(I) in the association with Hsp90. As a previous report demonstrated that the amino (N)-terminal 323 amino acids of Ago2 are sufficient to interact with Hsp90 in vitro (48), we speculate that hydroxylated Pro700 cooperates with the N-terminal region of Ago2 to form an interface between Ago2 and Hsp90 in vivo.

Fig. 4.

C-P4H(I)-mediated prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 promotes the interaction between Ago2 and Hsp90. (A) Total cell lysates from PASMCs treated with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Hsp90 antibody and immunoblotted with anti-Ago2 antibody. Total cell lysates were also subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-Ago2, anti-Hsp90, or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies. (B) Total cell lysates from PASMCs transfected with siRNA against C-P4Hα(I) (si-P4Hα) or nontargeting control (si-Ctr) siRNA for 48 h prior to treatment with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Ago2 antibody and immunoblotted with anti-Hsp90 antibody. Total cell lysates were also subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-C-P4Hα, anti-Ago2, anti-Hsp90, or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies (left panel). By densitometry, relative amounts of Hsp90, C-P4Hα, and Ago2 proteins normalized to β-actin were quantitated and are presented (right panel). (C) U2OS cells were transfected with vector (mock), Flag-tagged Ago22(WT), or Flag-tagged Ago2(mut) cDNA construct and treated with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Hsp90 antibody. Total cell lysates were also subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-Flag (for Ago2), anti-Hsp90, or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies.

Hypoxia increases Ago2 function.

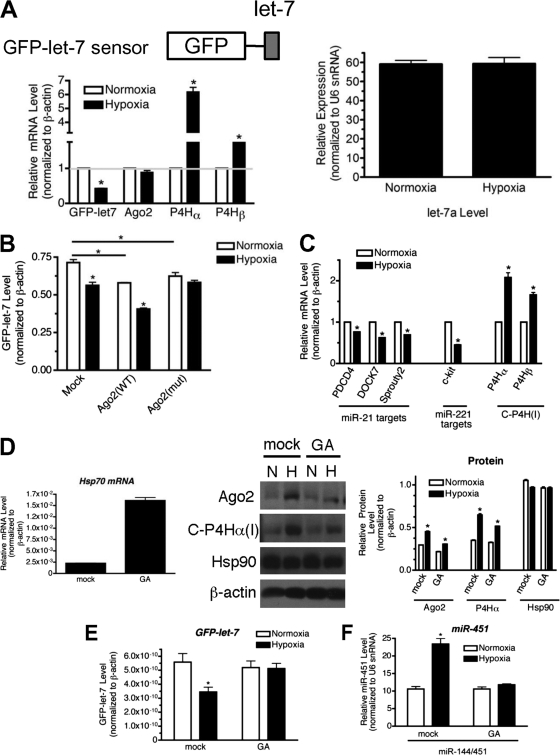

As hypoxia promotes the association of Ago2 with Hsp90, which is critical for the loading of small RNA duplexes into RISC (21), we speculated that hypoxia may increase RISC activity. A sequence perfectly complementary to let-7 was ligated to the 3′UTR of the GFP gene (GFP-let-7 sensor) and stably transfected into U2OS cells. Hypoxia treatment decreased the GFP-let-7 sensor mRNA expression to 40% of the normoxia level (Fig. 5A, lower left panel). Because endogenous let-7a levels were not altered by hypoxia (Fig. 5A, right panel), this result suggests that the let-7-RISC activity was elevated upon hypoxia presumably due to an effect on Ago2. As was observed with PASMCs, the mRNA levels of C-P4Hα and C-P4Hβ were increased by hypoxia in U2OS cells (Fig. 5A, lower left panel). In U2OS cells transfected with Ago2(WT), let-7-RISC activity was induced by hypoxia similar to that in mock-treated cells; however, when Ago2(mut) was expressed, hypoxia no longer induced let-7-RISC activity (Fig. 5B). These results confirm that hypoxia-mediated prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 augments RISC activity. Finally, to investigate the effect of hypoxia-mediated induction of miRNAs on target gene expression, levels of expression of validated targets of miR-21 (PDCD4, DOCK7, and Sprouty2) (5) and miR-221 (c-kit) (10) were examined. Consistent with the hypoxia-mediated increase in the levels of miR-21 and miR-221 (Fig. 6A, left panel), the levels of the targets of these miRNAs were significantly downregulated by hypoxia (Fig. 5C). In summary, these results demonstrate that hypoxia-mediated induction of Ago2 results in the elevation of various Ago2 functions, including RISC activity and Dicer-like processing activity (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 5.

Hypoxia increases Ago2 activity. (A) U2OS cell line stably expressing the GFP-let-7 sensor construct (upper left panel) was exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of GFP-let-7, Ago2, C-P4Hα, and C-P4Hβ mRNAs or let-7a miRNA. Relative levels of mRNA expression normalized to β-actin are presented by setting the expression levels of normoxia to 1 (lower left panel). Relative expression levels of let-7a normalized to U6 snRNA are presented (right panel). *, P < 0.05. (B) U2OS cell line stably expressing GFP-let-7 was transfected with vector (mock), wild-type (WT) Ago2, or Pro700A mutant (mut) Ago2 cDNA construct followed by treatment with normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h. Relative expression of the GFP-let-7 sensor was measured by qRT-PCR analysis and is presented after normalization to β-actin. *, P < 0.05. (C) PASMCs were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of miR-21 target gene (PDCD4, DOCK7, and Sprouty2) transcripts and miR-221 target gene (c-kit) transcripts. Relative levels of mRNA expression normalized to β-actin are presented by setting the expression levels of normoxia to 1. C-P4Hα(I) and C-P4Hβ mRNAs were examined as controls for hypoxia treatment. *, P < 0.05. (D) PASMCs were treated with mock (DMSO) or 0.1 μM geldanamycin (GA) for 1.5 h prior to exposure to normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h. Total RNAs extracted from the cells were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of Hsp70 mRNA as a control. Relative levels of mRNA expression normalized to β-actin are presented (left panel). Total cell lysates from the same cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis of Ago2, C-P4Hα(I), Hsp90, or β-actin (loading control) antibodies (middle panel). Relative amounts of proteins normalized to β-actin were quantitated by densitometry and are presented (right panel). *, P < 0.05. (E) U2OS cell line stably expressing GFP-let-7 was treated with mock (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) or 1 μM geldanamycin (GA) for 1.5 h prior to exposure to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h. Relative expression of the GFP-let-7 sensor was measured by qRT-PCR analysis and is presented after normalization to β-actin. *, P < 0.05. (F) U2OS cells transfected with miR-144/451 expression construct were treated with mock (DMSO) or 1 μM geldanamycin (GA) for 1.5 h prior to exposure to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h. Levels of miR-451 normalized to U6 snRNA are presented. *, P < 0.05.

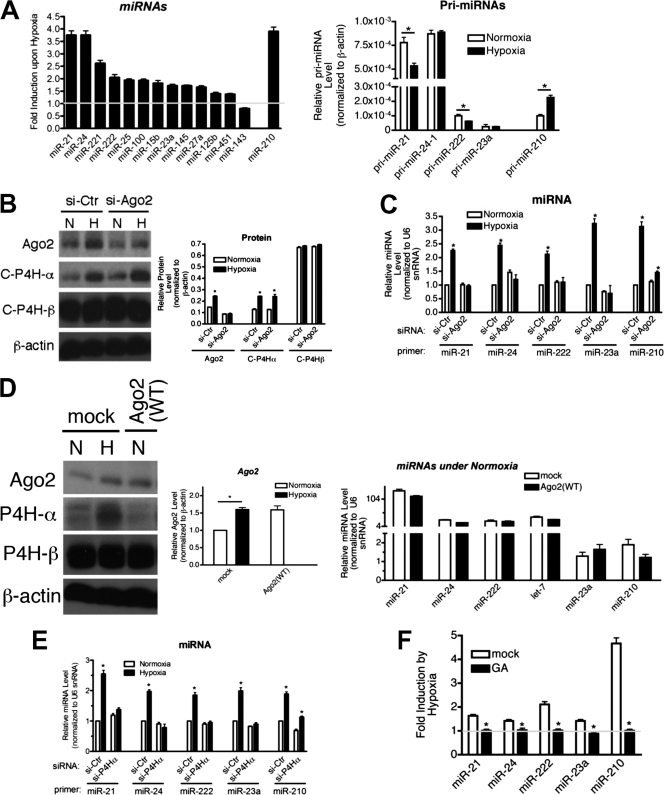

Fig. 6.

C-P4H(I)-mediated prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 is required for the induction of miRNAs upon hypoxia. (A) Levels of expression of miRNAs normalized to U6 snRNA were examined by qRT-PCR in PASMCs exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h. Fold induction (hypoxia/normoxia) is presented (left panel). Relative expression levels of pri-miRNAs normalized to β-actin were examined by qRT-PCR in PASMCs exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h (right panel). (B) PASMCs were transfected with siRNA against Ago2 (si-Ago2) or nontargeting control (si-Ctr) for 48 h prior to treatment with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h. Protein levels of Ago2, C-P4Hα, and C-P4Hβ were measured by immunoblotting (left panel), and relative amounts of proteins normalized to β-actin were quantitated by densitometry (right panel). *, P < 0.05. (C) miRNA analysis was conducted in the same cells used in panel B. Relative levels of miRNA expression normalized to U6 snRNA are presented by setting the miRNA expression levels of the si-Ctr under normoxia to 1. *, P < 0.05. (D) U2OS cells were transfected with vector (mock) or Ago2(WT) cDNA construct followed by treatment with normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H) for 24 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-Ago2, anti-C-P4Hα, anti-C-P4Hβ, or anti-β-actin (loading control) antibodies (left panel). By densitometry, relative amounts of Ago2 protein normalized to β-actin were quantitated and are presented (middle panel). Total RNAs were extracted from the same cells and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated miRNAs. Relative levels of miRNA expression normalized to U6 snRNA are presented (right panel). (E) PASMCs were transfected with siRNA against C-P4Hα(I) (si-P4Hα) or nontargeting control (si-Ctr) for 48 h prior to treatment with normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h. Total RNAs were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated miRNAs. Relative levels of miRNA expression normalized to U6 snRNA are presented by setting the miRNA expression levels of the si-Ctrl under normoxia to 1. *, P < 0.05. (F) miRNA analysis was conducted in PASMCs treated with mock (DMSO) or 0.1 μM geldanamycin (GA) for 1.5 h prior to exposure to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h. Levels of expression of the indicated miRNAs normalized to U6 snRNA were measured, and fold induction (hypoxia/normoxia) is presented.

Since Hsp90 is an ATPase and is required for the loading of miRNA or siRNA into RISC (21), we examined the effect of inhibition of the ATPase activity of Hsp90 on hypoxia-induced Ago2 activities. Cells were treated with geldanamycin (GA), a specific inhibitor of the ATPase activity of Hsp90, prior to hypoxia treatment. GA treatment increased the Hsp70 mRNA level as previously reported (45), confirming inhibition of Hsp90 by GA (Fig. 5D, left panel). The hypoxia-induced increase in Ago2 protein level was not significantly inhibited by GA (Fig. 5D, middle and right panels), showing that ATP hydrolysis by Hsp90 is not required for hypoxia-mediated accumulation of Ago2. Next, hypoxia-mediated induction of the RISC activity (GFP-let-7) and miR-451 processing activity was examined after GA treatment. Downregulation of the GFP-let-7 sensor mRNA expression by hypoxia was abolished by GA treatment (Fig. 5E), indicating that the ATPase activity of Hsp90 is essential for the induction of the RISC activity upon hypoxia, presumably because GA blocks the loading of the miRNA duplex into RISC. Furthermore, hypoxia-mediated induction of the miR-451 processing activity of Ago2 was blocked by GA treatment (Fig. 5F), indicating that the ATPase activity of Hsp90 is also required for the Dicer-like processing activity of Ago2. These results demonstrate the functional importance of Ago2-Hsp90 interaction in various Ago2 functions regulated by hypoxia.

Ago2 and C-P4H(I) are essential for the hypoxia-mediated increase in miRNAs.

To examine the potential effect of hypoxia on miRNA expression, miRNA microarray analysis was performed in PASMCs treated with hypoxia for 24 h. Thirty-seven percent of 292 miRNAs (107 miRNAs) detected in PASMCs were induced ≥1.5-fold upon hypoxia (Table 1). Furthermore, when C-P4Hα was knocked down by siRNA, 94% of the hypoxia-induced miRNAs (101 of 107 miRNAs) were either no longer induced by hypoxia or had reduced induction by hypoxia (Table 1). This result suggests a potential relationship between hydroxylation of Ago2 and elevation of miRNA expression. Induction of 14 miRNAs by hypoxia between ∼1.3- and 4-fold was validated by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 6A, left panel). miR-210 gene transcription is known to be activated by HIF-1 (1, 25). Indeed, ∼2-fold induction of the primary transcript of miR-210 (pri-miR-210) was observed upon hypoxia (Fig. 6A, right panel). However, primary transcripts of all other miRNAs examined were not induced and were rather repressed under hypoxia (Fig. 6A, right panel). These results suggest that hypoxia elevates the miRNAs through a posttranscriptional mechanism.

Table 1.

List of miRNAs induced by hypoxia ≥1.5-fold compared to normoxiaa

| miRNA | Fold induction (hypoxia vs. normoxia) |

|---|---|

| hsa-miR-576-3p | 53.2234814 |

| hsa-miR-383 | 21.13556796 |

| hsa-miR-199b-5p | 16.46910188 |

| hsa-miR-425* | 16.27652682 |

| hsa-miR-376a* | 13.27867211 |

| hsa-miR-192 | 12.5246812 |

| hsa-miR-454* | 12.12761518 |

| hsa-miR-361-5p | 6.138609836 |

| hsa-miR-500 | 5.780731148 |

| hsa-miR-181c | 5.69543477 |

| hsa-miR-431 | 5.500615181 |

| hsa-miR-363 | 4.348633054 |

| hsa-miR-139-5p | 4.243406757 |

| hsa-miR-589 | 4.029413817 |

| hsa-miR-301b | 3.491318505 |

| hsa-miR-135b | 3.366347188 |

| hsa-miR-198 | 3.304449565 |

| hsa-miR-369-5p | 3.219712737 |

| hsa-miR-337-5p | 3.187788638 |

| hsa-miR-221* | 3.153091369 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | 3.096923995 |

| hsa-miR-628-5p | 3.033938784 |

| hsa-miR-433 | 2.70462575 |

| hsa-miR-29a* | 2.660408852 |

| hsa-miR-302b | 2.64615391 |

| hsa-let-7d | 2.531088542 |

| hsa-miR-770-5p | 2.485398137 |

| hsa-miR-212 | 2.478599159 |

| hsa-miR-660 | 2.449000344 |

| hsa-miR-138 | 2.442341563 |

| hsa-miR-140-3p | 2.402935588 |

| hsa-miR-15b | 2.399289054 |

| hsa-miR-125a-3p | 2.38119204 |

| hsa-miR-642 | 2.373083684 |

| hsa-miR-29b | 2.315532452 |

| hsa-miR-221 | 2.313788469 |

| hsa-miR-20b | 2.272368763 |

| hsa-miR-493* | 2.239604488 |

| hsa-miR-26b | 2.236613507 |

| hsa-miR-382 | 2.236390275 |

| hsa-miR-130b* | 2.210460534 |

| hsa-miR-16 | 2.20144069 |

| hsa-miR-597 | 2.141108605 |

| hsa-let-7g | 2.101226925 |

| hsa-miR-93 | 2.092896513 |

| hsa-miR-21 | 2.070173919 |

| hsa-miR-455-3p | 2.05066663 |

| hsa-miR-342-3p | 2.031254454 |

| hsa-miR-103 | 2.028426428 |

| hsa-miR-186 | 2.020715164 |

| hsa-miR-362-3p | 1.992525208 |

| hsa-miR-632 | 1.968282059 |

| hsa-miR-20a* | 1.966616942 |

| hsa-miR-455-5p | 1.958946472 |

| hsa-miR-19a | 1.954962558 |

| hsa-miR-493 | 1.949407874 |

| hsa-miR-137 | 1.946221586 |

| hsa-miR-579 | 1.933023232 |

| hsa-miR-335 | 1.930097833 |

| hsa-miR-340 | 1.92955742 |

| hsa-miR-409-5p | 1.909437868 |

| hsa-miR-494 | 1.890645626 |

| hsa-miR-204 | 1.880614278 |

| hsa-miR-20a | 1.87133387 |

| hsa-miR-128 | 1.869917962 |

| hsa-miR-106b | 1.854641029 |

| hsa-miR-495 | 1.852372156 |

| hsa-miR-17 | 1.835091471 |

| hsa-miR-27a | 1.828833805 |

| hsa-miR-886-5p | 1.824078701 |

| hsa-miR-126 | 1.821881312 |

| hsa-miR-125a-5p | 1.799267857 |

| hsa-miR-134 | 1.790975965 |

| hsa-miR-132 | 1.780357512 |

| hsa-miR-195 | 1.760950037 |

| hsa-miR-29c | 1.760299579 |

| hsa-miR-7-1* | 1.756692865 |

| hsa-miR-19b | 1.755060759 |

| hsa-miR-26a | 1.755036429 |

| hsa-miR-339-3p | 1.741028689 |

| hsa-miR-539 | 1.737625255 |

| hsa-miR-365 | 1.720979577 |

| hsa-let-7e | 1.709293305 |

| hsa-miR-130a | 1.708838405 |

| hsa-miR-27b | 1.696146726 |

| hsa-let-7c | 1.681050397 |

| hsa-miR-18a | 1.662118194 |

| hsa-miR-140-5p | 1.657469102 |

| hsa-miR-34a | 1.651985446 |

| hsa-miR-15a* | 1.649646582 |

| hsa-miR-296-5p | 1.643090536 |

| hsa-miR-146b-5p | 1.623858559 |

| hsa-miR-143 | 1.6151498 |

| hsa-miR-10a | 1.611821493 |

| hsa-let-7b | 1.610126431 |

| hsa-miR-7 | 1.594098721 |

| hsa-miR-618 | 1.586598375 |

| hsa-miR-24 | 1.583246595 |

| hsa-miR-376c | 1.573787742 |

| hsa-miR-374b | 1.564888619 |

| hsa-miR-101 | 1.550530577 |

| hsa-miR-106a | 1.549648461 |

| hsa-miR-223 | 1.520878577 |

| hsa-miR-301a | 1.512485149 |

| hsa-miR-454 | 1.504819007 |

| hsa-miR-487b | 1.498771009 |

| hsa-miR-210 | 1.46457084 |

miRNAs whose induction was abolished (shaded and bolded) or reduced (shaded) when C-P4Hα was knocked down are indicated. Nonshaded miRNAs are those whose induction was not affected by C-P4Hα knockdown.

To investigate a potential link between Ago2 and the hypoxia-mediated induction of miRNAs, Ago2 was knocked down by siRNA (si-Ago2) in PASMCs. Transfection of si-Ago2 reduced ∼70% of the endogenous Ago2 mRNA and ∼50% of the Ago2 protein level (Fig. 6B). Knockdown of Ago2 had no effect on the hypoxia-mediated induction of C-P4Hα (Fig. 6B). Hypoxia-mediated increase in the miRNAs examined was either abolished or reduced when Ago2 was knocked down (Fig. 6C), suggesting that Ago2 plays an essential role in the accumulation of miRNAs in response to hypoxia. However, compared to the miRNAs whose hypoxia-mediated induction was completely abolished by si-Ago2, miR-210, which is transcriptionally regulated by HIF-1, was less affected by the knockdown of Ago2 and exhibited a weak increase upon hypoxia (Fig. 6C).

If the hypoxia-mediated increase in Ago2 protein were sufficient for the induction of miRNAs, then overexpression of Ago2(WT) to the level equivalent to that of hypoxia treated cells might be sufficient to induce miRNAs. To test this possibility, U2OS cells were transfected with an empty vector (mock) or Ago2(WT) expression construct, followed by exposure to hypoxia. Although Ago2(WT)-transfected cells expressed Ago2 at levels similar to that of mock-transfected cells under hypoxia (Fig. 6D, left and middle panels), mature miRNA levels were unchanged (Fig. 6D, right panel), suggesting that hypoxia-induced prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 is required for the induction of miRNAs. Furthermore, downregulation of C-P4H(I) activity by si-P4Hα, which downregulated ∼97% of endogenous C-P4Hα (Fig. 2D), either abolished or reduced the hypoxia-mediated induction of all miRNAs examined (Fig. 6E). These results indicate that prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 is critical for the elevation of miRNAs in response to hypoxia. Again, compared to the miRNAs whose hypoxia-mediated induction was completely abolished by si-P4Hα, HIF-1-regulated miR-210 was less affected by the knockdown of C-P4Hα and exhibited a modest increase upon hypoxia (Fig. 6E). As prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 by C-P4H(I) promotes the association of Ago2 with Hsp90, we hypothesized that induction of the miRNAs by hypoxia is dependent on the ATPase activity of Hsp90. Cells were treated with GA, followed by hypoxia treatment and miRNA analysis. All miRNAs examined failed to accumulate upon hypoxia under GA treatment (Fig. 6F). Because HIF-1 activity also requires the ATPase activity of Hsp90 (33), induction of HIF-1-dependent miR-210 was also abolished by GA treatment (Fig. 6F). Altogether, these results demonstrate that hypoxic stress mediates a series of nontranscriptional events: (i) prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 by C-P4H(I), (ii) formation of SGs and translocation of Ago2 to SGs, (iii) association of Ago2 with Hsp90, and (iv) an increase in Ago2 activity and miRNAs, all of which contribute to efficient gene silencing by miRNAs under low oxygen stress.

DISCUSSION

Chronic exposure of animals to hypoxia induces pulmonary artery remodeling and elevation of pulmonary artery pressure, similar to that seen in PAH patients (47). The small pulmonary arteries of animals treated with chronic hypoxia and those of PAH patients exhibit a significant increase in extracellular matrix proteins, including collagen deposits (36). A hypoxic environment is known to facilitate the formation of collagen deposits during the process of wound healing in skin or the remodeling of small pulmonary arteries by inducing procollagen, as well as C-P4H(I), which generates covalent cross-bridging between collagen fibers (35). Although molecular oxygen (O2) is required for the activity of C-P4H(I) (16), several studies have in fact shown that the activity of collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase is induced, rather than inhibited, under low oxygen tension (30, 39, 49). Exposure of fibroblasts to 24 h of hypoxia increased the activity of collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase by about 4-fold compared to normoxia and enhanced the degree of proline hydroxylation in newly synthesized collagen (30). Hypoxic exposure of fibroblasts also increased the levels of hydroxyproline residue secreted from the cells into the culture medium (49). These results demonstrate that the hydroxylation activity of collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase is regulated differently compared to that of the related prolyl hydroxylase domain protein (PHD), whose activity is known to be inhibited by hypoxia (16).

The PHDs are well-known regulators of the HIF-1α transcription factor (16). Under normoxia, PHDs hydroxylate HIF-1α, and this hydroxylation leads to the proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α (16). The activity of PHDs is inhibited under hypoxia; as a result, HIF-1α is no longer hydroxylated and accumulates in the cell to regulate the transcription of a variety of genes that are critical for conferring hypoxia tolerance (16). Like collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase, O2 is required for PHD activity (16); thus, it is not surprising that the activity of PHDs would be inhibited under conditions of low oxygen tension. While it may seem paradoxical that hypoxia induces the hydroxylation activity of collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase, an important difference between collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase and the PHDs is that the PHDs have a much higher Km value for O2, and thus a lower affinity for O2, compared to collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase (18). The Km values of the PHDs range from 230 μM to 250 μM, slightly above the concentration of dissolved O2 in the atmosphere, while the Km of type I collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase is only 40 μM (18). This significant difference between their Km values for O2 could contribute to the differential regulation of their hydroxylation activities under low oxygen tension. Even though the concentration of O2 is reduced under hypoxia, the hydroxylation activity of C-P4H(I) would still be maintained because of its relatively high oxygen affinity. This maintenance of activity would correlate with the important role that C-P4H(I) plays in the formation of collagen deposits under hypoxic conditions. Moreover, hypoxia has been shown to upregulate C-P4Hα(I), the subunit which is critical for the catalytic activity of C-P4H(I), at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (13, 14, 19). Thus, the relatively high oxygen affinity of C-P4H(I) along with the hypoxia-mediated increase in C-P4Hα(I) expression could lead to increased prolyl-hydroxylation of its substrates under hypoxia.

In this study, we characterized a role of Ago2 downstream of the hypoxia-mediated induction of C-P4H(I) activity and downstream effects of the miRNA pathway as an alternative mechanism of regulation of gene expression in cells under hypoxia. As Ago proteins are the key components of the RISC, regulation of Ago protein stability and/or activities has a significant impact on the silencing activities of siRNAs and miRNAs. It is increasingly evident that posttranslational modifications of Ago proteins, including phosphorylation and ubiquitination, modulate Ago protein stability and function, which subsequently alter gene expression (12). It is unclear, however, how such modifications are induced and how such modifications affect Ago protein functions. In this study, we demonstrate a functional significance of prolyl-hydroxylation of Ago2 which is mediated by hypoxia treatment. We are able to extend the significance of hydroxylation of Ago2 from modulation of Ago2 protein stability to modulation of the localization of Ago2 and its activities. Recently, induction of poly(ADP-ribosylation) of Ago proteins by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 13 (PARP-13) upon oxidative stress or translation initiation inhibition has been reported (29). Unlike hydroxylation, poly(ADP-ribosylation) of Ago relieves miRNA-mediated gene silencing, presumably due to disruption of electrostatic interaction or steric hindrance between the miRNA/Ago complex and target mRNA (29). It is plausible that different cellular stresses might mediate distinct posttranslational modifications of Ago to modulate miRNA-mediated gene silencing activity.

The molecular pathways in response to hypoxia are complex, but the transcription factor HIF-1 is known to play a key role by orchestrating the expression of a wide variety of genes that are critical for hypoxic tolerance (44). Our result that hypoxia mediates the accumulation of Ago2 in a C-P4H(I)-dependent manner is interesting because this is a second mechanism, in addition to HIF-1-mediated transcriptional regulation, that cells under low oxygen stress can use to modulate gene expression. It is particularly intriguing that a critical enzyme in the miRNA biogenesis pathway, Dicer, is strongly suppressed under hypoxia not only in cultured PASMCs or U2OS cells but also in the lungs of rats treated with chronic hypoxia (2). Furthermore, a reduction of Dicer mRNA was observed in rat pulmonary artery fibroblasts after chronic hypoxia treatment (2), suggesting that downregulation of Dicer upon hypoxia treatment is not limited to a specific cell type. Thus, we speculate that the modulation of localization and activities of Ago2 serves as an alternative mechanism to augment miRNA-mediated gene regulation under a condition of limited amount of Dicer in the cell.

Consistent with our observation in PASMCs, miR-451 was reported as one of the few miRNAs significantly induced in lungs from rats treated with chronic hypoxia (2). Interestingly, similar to our result in PASMCs, lungs from rats exposed to hypoxia also show a ∼40% decrease in Dicer expression compared to normoxia-treated samples (2). These in vivo hypoxia results are consistent with our observation that under the condition when Dicer is repressed, miR-451 can be induced through activation of Ago2 because the maturation of miR-451, unlike those of other miRNAs, does not require Dicer. Decreased expression of Dicer is also observed in various pathological conditions, such as cancer (26, 27) and severe respiratory syncytial virus disease (20). It is intriguing to speculate that miR-451 and potentially other miRNAs that are processed by Ago2 might play a critical role during the pathogenesis of these disorders.

SGs are known to be sites where nontranslating mRNAs accumulate when cells experience various stresses, such as oxidative stress (e.g., arsenite), translational inhibition (e.g., hippuristanol), UV damage, osmotic stress, or heat shock (22). More recently, Ago proteins were also found to localize to SGs in an miRNA-dependent manner (28). Therefore, the SG has been suggested to be a site where Ago2 and miRNAs actively silence target mRNAs (22). In this study, we demonstrated that hypoxia mediates the formation of SGs and translocation of Ago2 to SGs. Hypoxia-mediated SG formation is rapid and reaches a maximum level after 3 h and then gradually decreases by 24 h. Interestingly, the percentage of SG-positive cells after hypoxia, even at the time point of maximal SG formation, is ∼10 to 15%, unlike after arsenite treatment, where nearly all cells form SGs (data not shown). This might suggest that (i) hypoxia-induced SGs have a quick turnover or (ii) hypoxia-induced SG formation is dependent on other conditions, such as cell cycle phase. Consistent with the latter possibility, SG formation mediated by UV damage was reported to occur only in G1- and G2-phase cells (40). Furthermore, we observed that cells exposed to arsenite formed SGs with an average of ∼60 SGs/cell (data not shown), unlike those exposed to hypoxic stress, which formed an average of ∼15 SGs/cell in less than 15% of cells (Fig. 3B, left panel). It was also evident that the SGs induced by hypoxia are substantially larger than the arsenite-induced SGs, suggesting that the components of SGs mediated by these two different stresses might be distinct. Despite differences in the number and size of SGs, nearly all of the Ago2 translocated to SGs upon either arsenite (data not shown) or hypoxia (Fig. 3C) treatment. However, localization of Ago2 to SGs alone is not sufficient for the increase in Ago2, Ago2 activities, or the accumulation of miRNAs, as arsenite treatment did not alter the mRNA or protein levels of Ago2 or C-P4H(I) and miRNA expression was reduced upon arsenite treatment (data not shown), rather than increased, as was observed for hypoxia treatment. Furthermore, both the miR-451 processing activity of Ago2 and RISC activity (data not shown) were decreased after arsenite treatment. Although SGs induced by different stresses mostly contain TIA-1, a number of studies have indicated that SGs are not all identical in terms of their protein contents. For example, heat shock-induced SGs contain Hsp27, while arsenite-induced SGs do not (23). Both arsenite-induced SGs and hypoxia-induced SGs are dependent on the phosphorylation of eIF2α (15, 32). In addition, colocalization of Ago2 with SGs induced by hippuristanol, an inhibitor of eIF4A, is miRNA dependent (28). Our observation that Ago2 colocalizes with arsenite-induced SGs but has no significant effect on Ago2 activities and accumulation of miRNAs may suggest that the Ago2 localized in arsenite-induced SGs lacks critical factors, such as miRNAs, target mRNAs, or proteins other than Ago2, that are required for RISC activity.

Ago proteins can also be found in the nucleus (12). Although the exact mechanism of Ago function in the nucleus is unclear, it is suggested that it might play a role in transcriptional gene silencing by guiding DNA or histone H3 lysine methylation (12). It is interesting to speculate that hypoxia-mediated prolyl-hydroxylation might also affect the nuclear functions of Ago proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eric Lai for the miR-144/451 expression construct. We also thank Tomoya Uchimura for technical support.

This work was supported by grants from the NHLBI (HL093154), LeDucq Foundation, and American Heart Association (to A.H.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Camps C., et al. 2008. hsa-miR-210 is induced by hypoxia and is an independent prognostic factor in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 14:1340–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caruso P., et al. 2010. Dynamic changes in lung microRNA profiles during the development of pulmonary hypertension due to chronic hypoxia and monocrotaline. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30:716–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan M. C., et al. 2010. Molecular basis for antagonism between PDGF and the TGFbeta family of signalling pathways by control of miR-24 expression. EMBO J. 29:559–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheloufi S., Dos Santos C. O., Chong M. M., Hannon G. J. 2010. A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature 465:584–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng Y., Zhang C. 2010. MicroRNA-21 in cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 3:251–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cowland J. B., Hother C., Gronbaek K. 2007. MicroRNAs and cancer. APMIS 115:1090–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Croce C. M., Calin G. A. 2005. miRNAs, cancer, and stem cell division. Cell 122:6–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cullen B. R. 2006. Viruses and microRNAs. Nat. Genet. 38(Suppl.):S25–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis B. N., Hilyard A. C., Lagna G., Hata A. 2008. SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature 454:56–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis B. N., Hilyard A. C., Nguyen P. H., Lagna G., Hata A. 2009. Induction of microRNA-221 by platelet-derived growth factor signaling is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 284:3728–3738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eisenberg I., Alexander M. S., Kunkel L. M. 2009. miRNAS in normal and diseased skeletal muscle. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13:2–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ender C., Meister G. 2010. Argonaute proteins at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 123:1819–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fahling M., et al. 2006. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein-A2/B1 modulate collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase, alpha (I) mRNA stability. J. Biol. Chem. 281:9279–9286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fahling M., et al. 2006. Translational control of collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase-alpha(I) gene expression under hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 281:26089–26101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gardner L. B. 2008. Hypoxic inhibition of nonsense-mediated RNA decay regulates gene expression and the integrated stress response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:3729–3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gorres K. L., Raines R. T. 2010. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 45:106–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris A. L. 2002. Hypoxia—a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hirsila M., Koivunen P., Gunzler V., Kivirikko K. I., Myllyharju J. 2003. Characterization of the human prolyl 4-hydroxylases that modify the hypoxia-inducible factor. J. Biol. Chem. 278:30772–30780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hofbauer K. H., et al. 2003. Oxygen tension regulates the expression of a group of procollagen hydroxylases. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:4515–4522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inchley C. S., Sonerud T., Fjaerli H. O., Nakstad B. 2011. Reduced Dicer expression in the cord blood of infants admitted with severe respiratory syncytial virus disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 11:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iwasaki S., et al. 2010. Hsc70/Hsp90 chaperone machinery mediates ATP-dependent RISC loading of small RNA duplexes. Mol. Cell 39:292–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kedersha N., Anderson P. 2007. Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol. 431:61–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kedersha N. L., Gupta M., Li W., Miller I., Anderson P. 1999. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2 alpha to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J. Cell Biol. 147:1431–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim V. N. 2005. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kulshreshtha R., et al. 2007. A microRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:1859–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumar M. S., Lu J., Mercer K. L., Golub T. R., Jacks T. 2007. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat. Genet. 39:673–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumar M. S., et al. 2009. Dicer1 functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 23:2700–2704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leung A. K., Calabrese J. M., Sharp P. A. 2006. Quantitative analysis of Argonaute protein reveals microRNA-dependent localization to stress granules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:18125–18130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leung A. K., et al. 2011. Poly(ADP-ribose) regulates stress responses and microRNA activity in the cytoplasm. Mol. Cell 42:489–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levene C. I., Bates C. J. 1976. The effect of hypoxia on collagen synthesis in cultured 3T6 fibroblasts and its relationship to the mode of action of ascorbate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 444:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu C. J. 2009. MicroRNAs in skeletogenesis. Front. Biosci. 14:2757–2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McEwen E., et al. 2005. Heme-regulated inhibitor kinase-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 inhibits translation, induces stress granule formation, and mediates survival upon arsenite exposure. J. Biol. Chem. 280:16925–16933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Minet E., et al. 1999. Hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1: role of HIF-1alpha-Hsp90 interaction. FEBS Lett. 460:251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Myllyharju J. 2008. Prolyl 4-hydroxylases, key enzymes in the synthesis of collagens and regulation of the response to hypoxia, and their roles as treatment targets. Ann. Med. 40:402–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Myllyharju J., Kivirikko K. I. 2004. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet. 20:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naeije R., Rondelet B. 2004. Pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Bull. Mem. Acad. R. Med. Belg. 159:219–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Owens G. K., Kumar M. S., Wamhoff B. R. 2004. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 84:767–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pare J. M., et al. 2009. Hsp90 regulates the function of argonaute 2 and its recruitment to stress granules and P-bodies. Mol. Biol. Cell 20:3273–3284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perhonen M., Han X., Wang W., Karpakka J., Takala T. E. 1996. Skeletal muscle collagen type I and III mRNA, [corrected] prolyl 4-hydroxylase, and collagen in hypobaric trained rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 80:2226–2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pothof J., Verkaik N. S., van IJcken I. W., et al. 2009. MicroRNA-mediated gene silencing modulates the UV-induced DNA-damage response. EMBO J. 28:2090–2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Preston I. R., Hill N. S., Warburton R. R., Fanburg B. L. 2006. Role of 12-lipoxygenase in hypoxia-induced rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 290:L367–L374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Qi H. H., et al. 2008. Prolyl 4-hydroxylation regulates Argonaute 2 stability. Nature 455:421–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rich S., et al. 1987. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Ann. Intern. Med. 107:216–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Semenza G. L. 2009. Regulation of oxygen homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Physiology (Bethesda) 24:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shu C. W., Cheng N. L., Chang W. M., Tseng T. L., Lai Y. K. 2005. Transactivation of hsp70-1/2 in geldanamycin-treated human non-small cell lung cancer H460 cells: involvement of intracellular calcium and protein kinase C. J. Cell. Biochem. 94:1199–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Siomi H., Siomi M. C. 2010. Posttranscriptional regulation of microRNA biogenesis in animals. Mol. Cell 38:323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stenmark K. R., Meyrick B., Galie N., Mooi W. J., McMurtry I. F. 2009. Animal models of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the hope for etiological discovery and pharmacological cure. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 297:L1013–L1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tahbaz N., Carmichael J. B., Hobman T. C. 2001. GERp95 belongs to a family of signal-transducing proteins and requires Hsp90 activity for stability and Golgi localization. J. Biol. Chem. 276:43294–43299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Takahashi Y., Takahashi S., Shiga Y., Yoshimi T., Miura T. 2000. Hypoxic induction of prolyl 4-hydroxylase alpha (I) in cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14139–14146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tsuji-Naito K., Ishikura S., Akagawa M., Saeki H. 2010. α-Lipoic acid induces collagen biosynthesis involving prolyl hydroxylase expression via activation of TGF-β-Smad signaling in human dermal fibroblasts. Connect. Tissue Res. 51:378–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang J. S., et al. 2010. Conserved vertebrate mir-451 provides a platform for Dicer-independent, Ago2-mediated microRNA biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15163–15168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]