Abstract

We report a diabetic patient who had three episodes of cryptogenic liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. He was a Caucasian who lived in California and had no epidemiological connection to East Asia. The isolate from his third episode was a hyperviscous K1 strain that carried the Klebsiella virulence plasmid.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 78-year-old man. In November 2010, he was admitted to the VA hospital because of fever, shortness of breath, and weakness for 2 days. He lived in a private residence in Chula Vista, CA, and his only travel outside the United States was to northern Mexico about 10 years prior. He had diabetes mellitus type 2 treated with diet, hypertension, glaucoma, peripheral arterial insufficiency, a history of a cerebrovascular accident with good functional recovery, paroxysmal atrial flutter/fibrillation, esophageal reflux, and prostatic hypertrophy. He denied any localizing symptoms, and his physical examination was unremarkable, except for a blood pressure of 80/50, a temperature of 102.8°F, and somnolence. His white blood cell count was 14,100/μl with 76% neutrophils and a few bands. His hemoglobin level was 12.3 g/dl, and his platelet count and liver function test were normal. His urinalysis showed pyuria but his urine grew only Candida glabrata. He was started on vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and intravenous fluids. Admission blood cultures were sterile. He was febrile for 2 days and complained of abdominal pain, which prompted an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan that revealed a liver abscess (Fig. 1 C). Antibiotics were changed to ceftriaxone, but he remained febrile for another 36 h until the abscess was drained percutaneously on the 5th hospital day. The aspirate grew a rare K. pneumoniae strain that was sensitive to all antibiotics except ampicillin. We continued ceftriaxone for a total of 30 days with complete radiographic resolution of the abscess.

Fig. 1.

CT scans of the liver. (A) Noncontrast CT scan done on 30 January 2008 with a hypoattenuating lesion in hepatic segment IV measuring 4 cm. (B) Noncontrast CT scan done on 22 July 2008 with a hypoattenuating lesion bridging hepatic segments VII and VIII and measuring 7 cm. (C) Noncontrast CT scan done on 10 November 2010 with a hypoattenuating lesion in hepatic segment VIII measuring 3.3 cm.

That was this man's third liver abscess in a 2-year period. His first abscess was in January 2008. His blood cultures were negative then, and the abscess was not drained because it was small and in an inaccessible location (Fig. 1A). He was treated empirically with piperacillin-tazobactam for 1 month. He became afebrile, and follow-up imaging showed a normal liver. Five months later, he has admitted to another hospital with fever and chills, and a CT scan of the abdomen showed an abscess that was in a different segment of his liver (Fig. 1B). This time, both his blood cultures and a liver aspirate grew a K. pneumoniae strain resistant only to ampicillin. He was treated with ceftriaxone and made a full recovery with normal liver imaging.

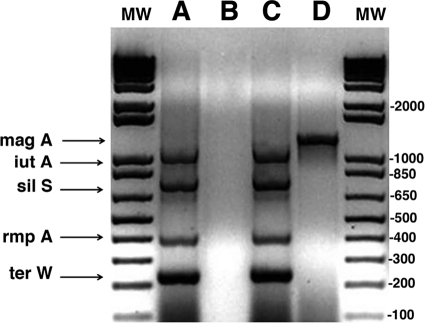

In the 1980s, a new syndrome of hematogenous liver abscess due to K. pneumoniae was recognized in Taiwan, and K. pneumoniae now accounts for 80 to 90% of all nonbiliary liver abscesses (13, 14). The isolates have a distinctive hyperviscous (HV) phenotype that correlates with mouse virulence (10). Although all of the virulence factors in those K. pneumoniae isolates have not been established, the majority of the isolates are K1 and so have the magA gene (2). More importantly, even non-K1 HV strains carry a virulence plasmid that is required for virulence in a mouse model of orally induced liver abscess (12), as is a chromosomal gene, kfu, that is part of an operon that encodes an iron uptake system (7). The isolate from our patient's third liver abscess carried a virulence plasmid and was a K1 strain, since it was magA positive (Fig. 2), establishing this pathogen as closely related to the epidemic strains in East Asia.

Fig. 2.

Bacteria were boiled in a PCR master mixture containing the primers for the plasmid genes (12), and then Taq polymerase was added. The primers for magA amplification were added to a separate mixture (3). PCR products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel. Lanes A and B are the standard strain containing the virulence plasmid (K. pneumoniae CG43) from H.-L. Tang, and lanes C and D are the patient's isolate. Lanes A and C are the products of the multiplex PCR for the virulence plasmid genes; B and D show magA. The clinical isolate was positive for all of the genes tested, identifying it as a K1 isolate containing the virulence plasmid genes. K. pneumoniae CG43 was a K2 strain, so it did not contain magA. Lanes MW contained molecular weight markers.

Most of the reported patients in Taiwan have had diabetes, as did our patient, but the role diabetes plays in this illness is not established. Cases of Klebsiella liver abscess (KLA) are still rare in the United States and Europe, and the majority of reported patients were Asian or Pacific Island immigrants (3, 4, 6, 9, 10a, 11). Nadasy et al. reported a Vietnamese-American who had visited Vietnam 5 years before his infection with a magA rmpA-positive HV K. pneumoniae isolate, implying the presence of the virulence plasmid (9). McCabe et al. reported 3 additional patients in northern California of Asian origin with KLA caused by HV K. pneumoniae (8). Our patient was a Caucasian man who lived for many years in southern California and had no epidemiological links to East Asia, and yet the isolate we obtained from his liver abscess was a K1 strain that was HV and carried the plasmid-contained genes from East Asian strains. Since the patient had no travel history and no personal link with anyone from East Asia, this is evidence that this virulent organism has become established in the United States.

Two other features of the case are of interest. First, he had three separate episodes of KLA. Although we did not prove that the first abscess was due to K. pneumoniae because his blood cultures were not positive and the abscess was not drained, his second and third episodes were culture-proven KLA. It is likely that these were not relapses, because each episode involved a different segment of his liver (Fig. 1) and each episode was treated until there was complete clinical and radiological resolution. In a longitudinal study in Taiwan, the 18-year rate of recurrent KLA in diabetics was nearly 6% (1). In the few recurrent cases that have been studied to determine if both episodes were due to the same organism, the isolates were not identical, as assessed by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (15). This implies that some people are predisposed to this infection. We are not aware of a prior report of recurrent KLA in a resident of the United States, and there are relatively few reports of multiple recurrences from Asia. Second, he twice presented with a liver abscess with negative blood cultures, so U.S. clinicians must consider KLA in the differential diagnosis of diabetics presenting with cryptogenic liver abscesses, even in the absence of positive blood cultures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yichyi Lai (Taiwan) for providing K. pneumoniae CG43 containing the virulence plasmid, Sharon Okamoto for maintaining the cultures, and Suganya Viriyakosol for help with the figures.

This study was supported by a VA Merit Review grant.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cheng H.-C., et al. 2008. Long-term outcome of pyogenic liver abscess: factors related with abscess recurrence. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 42:1110–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fang C. T., et al. 2004. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J. Exp. Med. 199:697–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fang F. C., Sandler N., Libby S. J. 2005. Liver abscess caused by magA+ Klebsiella pneumoniae in North America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:991–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frazee B. W., Hansen S., Lambert L. 2009. Invasive infection with hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae: multiple cases presenting to a single emergency department in the United States. Ann. Emerg. Med. 53:639–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reference deleted.

- 6. Lederman E. R., Crum N. F. 2005. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100:322–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma L.-C., Fang C. T., Lee C.-Z., Shun C.-T., Wang J.-T. 2005. Genomic heterogeneity in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains is associated with primary pyogenic liver abscess and metastatic infection. J. Infect. Dis. 192:117–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCabe R., Lambert L., Frazee B. 2010. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae infections, California, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:1490–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nadasy K. A., Domiati-Saad R., Tribble M. A. 2007. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae syndrome in North America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:e25–e28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nassif X., Fournier J.-M., Arondel J., Sansonetti P. 1989. Mucoid phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae is a plasmid-encoded virulence factor. Infect. Immun. 57:546–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a. Pomakova D. K., et al. 2011. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. [Epub ahead of print.] doi.10.1007/s10096-011-1396-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sobirk S. K., Struve C., Jacobson S. G. 2010. Primary Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess with metastatic spread to lung and eye, a North-European case report of an emerging syndrome. Open Microbiol. J. 4:5–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tang H.-L., et al. 2010. Correlation between Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying pLVPK-derived loci and abscess formation. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsai F.-C., Huang Y.-T., Chang L.-Y., Wang J.-T. 2008. Pyogenic liver abscess as endemic disease, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1592–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang J.-H., et al. 1998. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1434–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang Y. S., et al. 2009. Recurrent Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: clinical and microbiological characteristics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3336–3339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]