Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains one of the most significant causes of death from an infectious agent. The rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis and detection of rifampin (RIF) resistance are essential for early disease management. The GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay is a novel integrated diagnostic device for the diagnosis of tuberculosis and rapid detection of RIF resistance in clinical specimens. We determined the performance of the MTB/RIF assay for rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis and detection of rifampin resistance in smear-positive and smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens obtained from possible tuberculosis patients. Two hundred fifty-three pulmonary and 176 extrapulmonary specimens obtained from 429 patients were included in the study. One hundred ten (89 culture positive and 21 culture negative for M. tuberculosis) of the 429 patients were considered to have tuberculosis. In pulmonary specimens, sensitivities were 100% (27/27) and 68.6% (24/35) for smear-positive and smear-negative specimens, respectively. It had a lower sensitivity with extrapulmonary specimens: 100% for smear-positive specimens (4/4) and 47.7% for smear-negative specimens (21/44). The test accurately detected the absence of tuberculosis in all 319 patients without tuberculosis studied. The MTB/RIF assay also detected 1 RIF-resistant specimen and 88 RIF-susceptible specimens, and the results were confirmed by drug susceptibility testing. We concluded that the MTB/RIF test is a simple method, and routine staff with minimal training can use the system. The test appeared to be as sensitive as culture with smear-positive specimens but less sensitive with smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens that include low numbers of bacilli.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains one of the most significant causes of death from an infectious agent. The incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis in Turkey is nearly 27.9 per 100,000 population, according to the 2009 Tuberculosis Report in Turkey (19). The proportion of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis (TB) cases among new cases is 2.9%, that among previously treated cases is 15.5%, and that among all TB cases is 4.9% (19). The rapid detection of M. tuberculosis and rifampin (RIF) resistance in infected patients is essential for disease management, because of the high risk of transmission from person to person and emergence of MDR-TB and extensively drug resistant tuberculosis. Culture is the “gold standard” for final determination, but it is slow and may take up to 2 to 8 weeks. Although smear microscopy for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) is rapid and inexpensive, it has poor sensitivity and a poor positive predictive value (PPV). Thus, rapid identification, which is essential for earlier treatment initiation, improved patient outcomes, and more effective public health interventions, relies on nucleic acid amplification techniques (1).

Collectively, DNA sequencing studies demonstrate that more than 95% of RIF-resistant M. tuberculosis strains have a mutation within the 81-bp hot spot region of the rpoB gene (6, 15, 18). Several molecular methods have been developed in recent years for the diagnosis of tuberculosis and rapid detection of drug resistance in clinical specimens, including line probe assays (GenoType MTBDRplus [Hain Lifescience GmbH, Nehren, Germany], INNO LIPA Rif.TB [Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium]) and real-time PCR (GeneXpert MTB/RIF; Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA). Molecular assays have been established to allow the prediction of drug resistance in clinical specimens within 1 working day and are potentially the most rapid methods for the detection of drug resistance (3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15). The GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay is a novel integrated diagnostic device that performs sample processing and heminested real-time PCR analysis in a single hands-free step for the diagnosis of tuberculosis and rapid detection of RIF resistance in clinical specimens (3, 9). The MTB/RIF assay detects M. tuberculosis and RIF resistance by PCR amplification of the 81-bp fragment of the M. tuberculosis rpoB gene and subsequent probing of this region for mutations that are associated with RIF resistance. The assay can generally be completed in less than 2 h (3, 9).

The aim of this study was to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of tuberculosis and rapid detection of rifampin resistance in smear-positive and smear-negative pulmonary and nonpulmonary clinical specimens. The results obtained by the MTB/RIF assay were compared with the results obtained by culture and phenotypic susceptibility testing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples.

In this study, pulmonary and extrapulmonary samples obtained during the clinical routine and sent to the Ege University Medical Faculty, Department of Medical Microbiology, Mycobacteriology Laboratory, between February 2010 and November 2010 were investigated. A total of 253 pulmonary specimens (sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, bronchoscopic aspirate, postbronchoscopic sputum, and gastric fluid specimens) from 253 patients and a total of 176 extrapulmonary specimens (pleural fluid, lymph node biopsy, disc material, ascitic fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, pericardial fluid, skin biopsy, and urine specimens) from 176 patients were included in the study.

Nonsterile clinical specimens were processed by the conventional N-acetyl-l-cysteine–NaOH method (12). After decontamination, smears were prepared by the auramine-rhodamine acid-fast staining method. Decontaminated specimens were inoculated to Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) solid medium and MB/BacT liquid medium (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) for growth detection, and the leftover sediment of the decontaminated specimen was stored at −80°C. Smear-positive specimens were studied within 2 weeks at the latest; smear-negative specimens were studied immediately after growth of culture.

Identification of MTBC strains from cultures and DST.

After growth of the cultures and species identification and in cases in which Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) strains were identified, drug susceptibility testing (DST) was performed. The identification of M. tuberculosis from the grown cultures was confirmed by the GenoType MTBDR plus assay. The first positive culture from each specimen underwent DST. The proportional method with 7H10 agar medium was used to test for resistance to RIF. Tests were performed with the standard critical concentrations of RIF (8).

MTB/RIF assay.

The MTB/RIF assay was performed as described previously (3, 9, 17). Briefly, sample reagent was added at a 3:1 ratio to clinical specimens. The closed specimen container was manually agitated twice during a 15-min period at room temperature, before 2 ml of the inactivated material (equivalent to 0.5 ml of decontaminated pellet) was transferred to the test cartridge. All specimens that were culture positive and MTB/RIF assay negative and specimens that were culture negative and MTB/RIF assay positive were retested twice. The last result was used for the analysis.

Patient groups.

Patients were grouped as (i) those with smear- and culture-positive tuberculosis; (ii) those with smear-negative, culture-positive tuberculosis; (iii) those who were smear and culture negative for tuberculosis but who were nonetheless treated for tuberculosis on the basis of clinical, pathological, and/or radiological findings (clinical tuberculosis); and (iv) those with no bacteriological, clinical, pathological, or radiological evidence of tuberculosis (no tuberculosis). The final diagnosis for the culture-negative patients was established by the clinician. Patients who had been treated with anti-TB drugs for more than 7 days and who had received anti-TB treatment within the last 2 years were not included in the study.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS for Windows (version 16.0) software package. Numerical variables were summarized with mean ± standard deviation. The significance of differences among groups was assessed by the Student t test, and analysis of categorical variables was examined by the chi-square test. A value of P of <0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Patients.

Two hundred fifty-three pulmonary specimens and 176 extrapulmonary specimens obtained from 429 patients (median age, 47.5 ± 22.2 years; 247 males) were included in the study. One hundred ten of the 429 patients were considered to have tuberculosis, and 319 (median age, 48 ± 20 years; 179 males) of the 429 patients had no bacteriological, clinical, pathological, or radiological evidence of tuberculosis. Eighty-nine of the 110 tuberculosis patients (median age, 47 ± 23 years; 70 males) were culture positive. The remaining 21 patients were culture negative, but their clinical history and pathological and/or radiological evidence were sufficiently indicative of tuberculosis.

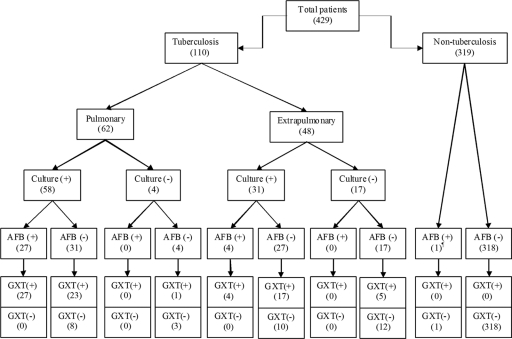

Of 253 pulmonary specimens, 58 were culture positive for M. tuberculosis. After obtaining a combination of culture results and clinical data, 62 patients had a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Of the 176 extrapulmonary specimens examined, 31 were culture positive for M. tuberculosis. After obtaining a combination of culture results and clinical data, 48 patients were diagnosed with extrapulmonary tuberculosis. The patient groups included in the study are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Results of conventional and diagnostic testing of patients included in the study. AFB, acid-fast bacilli; ¶, culture positive for M. intracellulare; GXT, GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay.

Sensitivity and specificity of MTB/RIF assay.

According to the results for 110 tuberculosis patients diagnosed clinically and microbiologically, the sensitivity of the MTB/RIF test was 70% (77/110), the specificity was 100% (319/319), the negative predictive value (NPV) was 90.6% (319/352), and the PPV was 100% (77/77). For pulmonary specimens, the sensitivity and specificity of the MTB/RIF test were 82.3% and 100%, respectively. The sensitivities were 100% and 68.6% for smear-positive and smear-negative specimens, respectively. For extrapulmonary specimens, the sensitivity and specificity were 52.1% and 100%, respectively. The sensitivity of the test was 100% (4/4) for smear-positive extrapulmonary specimens and 47.7% (21/44) for smear-negative extrapulmonary specimens.

According to culture results, the sensitivity of the MTB/RIF test was 79.7% (71/89), the specificity was 98.2% (334/340), NPV was 94.8% (334/352), and PPV 92.2% (71/77). The sensitivity of the MTB/RIF test was 100% (27/27) for smear-positive pulmonary specimens and 74.2% (23/31) for smear-negative pulmonary specimens. The sensitivity of the MTB/RIF assay according to the culture result was 100% (4/4) for smear-positive extrapulmonary specimens and 63% (17/27) for smear-negative extrapulmonary specimens. The sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV of the test for smear-positive and smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens are detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of various methods for all tuberculosis cases

| Method and specimen type | Pulmonary specimens |

Extrapulmonary specimens |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | NPV (%) | PPV (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | NPV (%) | PPV (%) | |

| Smear | 43.5 | 99.5 | 84.4 | 96.4 | 9.1 | 100 | 74.4 | 100 |

| Culture | 93.5 | 100 | 97.9 | 100 | 64.6 | 100 | 88.3 | 100 |

| MTB/RIF assay (total) | 82.3 | 100 | 94.6 | 100 | 52.1 | 100 | 85.3 | 100 |

| Smear positive | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Smear negative | 68.6 | 100 | 94.6 | 100 | 47.7 | 100 | 85.3 | 100 |

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of various methods according to culture results

| Method and specimen type | Pulmonary specimens |

Extrapulmonary specimens |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | NPV (%) | PPV (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | NPV (%) | PPV (%) | |

| Smear | 46.5 | 99.7 | 86.3 | 96.4 | 12.9 | 100 | 84.2 | 100 |

| MTB/RIF assay (total) | 86.2 | 99.4 | 96 | 98 | 67.7 | 96.5 | 93.2 | 80.7 |

| Smear positive | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Smear negative | 74.2 | 99.4 | 96 | 95.8 | 63 | 97.8 | 93.2 | 77.2 |

Detection of rifampin resistance.

Susceptibility testing was performed for all the culture-positive patients. Eighty-four patients were infected with M. tuberculosis strains susceptible to all primary drugs, three patients had strains resistant to a single drug (two to isoniazid [INH], one to ethambutol [EMB]), and two patients had strains resistant to more than one drug (one INH and EMB, one RIF and INH). The MTB/RIF assay detected 1 RIF-resistant specimen and 88 RIF-susceptible specimens, and the results were confirmed by DST.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the performance of the MTB/RIF assay with pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens obtained during the clinical routine was investigated. Previous studies of the MTB/RIF assay have reported test sensitivities of 57 to 76.9% in cases of smear-negative, culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis and 98 to 100% in cases of smear-positive, culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis, while the test specificity remained at 99% to 100% (2, 4, 5, 9, 14). In our study the sensitivity of the test with smear- and culture-positive pulmonary specimens was 100%, and the specificity was 98.3% (61/62), compatible with results presented in previous medical papers. For smear-negative pulmonary specimens, the sensitivity of the test was 74.2%, which is higher than that of Armand et al. (2) and congruent with the sensitivities of others.

In a study performed recently, the sensitivities of the test for smear-positive and smear-negative extrapulmonary specimens have been reported to be 100% and 37%, respectively (2). In the present study, the sensitivity of the test was also 100% for smear-positive extrapulmonary specimens, but in contrast to the findings of Armand et al. (2), our results with extrapulmonary specimens revealed 63% sensitivity for smear-negative specimens. In all tuberculosis cases, the sensitivity of the MTB/RIF test for pulmonary specimens was statistically higher than that for extrapulmonary specimens (P = 0.001). It could be because of the high smear-negative rate for nonrespiratory specimens. Even though the sensitivity of the MTB/RIFB test for culture-positive, smear-negative pulmonary specimens (74.2%) was higher than the sensitivity for culture-positive, smear-negative extrapulmonary specimens (63%), the difference was not statistically significant.

In our study, the MTB/RIF test detected the agent in 51 of 62 pulmonary specimens and 26 of 48 extrapulmonary specimens (13 of 17 lymph node biopsy specimens, 3 of 5 cerebrospinal fluid specimens, 3 of 5 tissue specimens, 3 of 4 disc biopsy specimens, 1 of 4 ascitic fluid specimens, 2 of 2 skin biopsy specimens, 1 of 1 pericardial fluid specimen, none of 1 bone marrow biopsy specimen, none of 1 urine specimen) obtained from 110 patients. In eight pleural tuberculosis cases, the MTB/RIF test was negative for all pleural fluid samples, even though four of them were culture positive. There was no significant difference between sample type and MTB/RIF performance among extrapulmonary specimens. Especially in pleural fluid samples, there was no positive test result; this could be due to very low numbers of bacilli or the presence of an inhibitory substance which inhibited the amplification of the M. tuberculosis genome without any effect on the internal control for pleural fluid samples.

For culture-positive specimens, the average turnaround time was 19 ± 9 days (range, 3 to 42 days) in liquid medium. The median turnaround time for smear-positive samples was statistically shorter for pulmonary specimens than extrapulmonary specimens. Also, all smear-positive and MTB/RIF test-positive samples had shorter turnaround times (P = 0.001). This could be the result of a low number of organisms in extrapulmonary specimens. A previous study found that the MTB/RIF assay had a calculated limit of detection of 131 CFU/ml of sputum and was able to detect as few as 10 CFU/ml of sputum in 35% of samples (9). In the study, the longer turnaround time for the MTB/RIF test-negative samples could be due to low numbers of bacilli which were under the limits of detection of the test.

In routine practice, the MTB/RIF test was quite faster (3 to 24 h) than culture, which required 19 days. The MTB/RIF test was positive for 71 of 89 culture-positive samples and 5 of 21 culture-negative samples from clinical tuberculosis cases. In our study, even though the sensitivity of the MTB/RIF test was found to be lower than that of culture, the test contributed to the diagnosis of 5 of 110 tuberculosis cases (4.6%). The sensitivity of microscopy was 46.6% (27/58) for culture-positive pulmonary specimens and 12.9% (4/31) for culture-positive extrapulmonary specimens. The MTB/RIF assay was positive for all of the smear-positive specimens, but the smear was positive only for 27 of 71 the MTB/RIF assay-positive specimens. The sensitivity of the MTB/RIF test, which was as rapid as smear, was much higher than that of smear.

In the previous studies, the sensitivity of the MTB/RIF test for detecting RIF resistance was 94.4 to 100% and the specificity was 98.3 to 100% (4, 5, 16). In our study, 1 RIF-resistant and 88 RIF-sensitive samples were detected correctly by the MTB/RIF test. In one sputum sample, which was smear 3+ and for which culture yielded M. intracellulare, the MTB/RIF test gave a negative result and even probes A and C gave positive signals. It is known that for tuberculosis detection the MTB/RIF assay software requires a sample to have at least two positive probes with a change in the cycle threshold value (ΔCT) of >2 cycles (9). In this study, the sample including M. intracellulare also did not produce ΔCT values that fulfilled the criteria for M. tuberculosis detection.

In conclusion, the MTB/RIF test is less dependent on the user's skills, and routine staff with minimal training can use the test. It has a short turnaround time and simultaneously detects M. tuberculosis and RIF resistance in less than 3 h. Although the MTB/RIF test could be a useful tool for rapid identification of RIF-resistant M. tuberculosis, especially in smear-positive clinical samples, the test results must always be confirmed by culture and DST.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant 2010/TIP/01 from the Ege University Medical Science Program.

For their support, we thank Kerem Ozturk from the Ear Nose Throat Surgery Department and Sedat Caglı from the Neurosurgery Department of the Faculty of Medicine, Ege University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anonymous. 2009. Updated guidelines for the use of nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58:7–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armand S., Vanhuls P., Delcroix G., Courcol R., Lemaître N. 2011. Comparison of the Xpert MTB/RIF test with an IS6110-TaqMan real-time PCR assay for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory and nonrespiratory specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1772–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blakemore R., et al. 2010. Evaluation of the analytical performance of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay. J. Cin Microbiol. 48:2495–2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boehme C. C., et al. 2010. Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 363:1005–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boehme C. C., et al. 2011. Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decentralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance: a multicentre implementation study. Lancet 377:1495–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cavusoglu C., Hilmioglu S., Guneri S., Bilgic A. 2002. Characterization of rpoB mutations in rifampin-resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Turkey by DNA sequencing and line probe assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4435–4438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cirillo D. M., et al. 2004. Direct rapid diagnosis of rifampicin resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in clinical samples by line probe assay (INNO LiPA Rif. TB). New Microbiol. 27:221–227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. CLSI/NCCLS. 2003. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardia, and other aerobic actinomycetes; approved standard. Document M24-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Helb D., et al. 2010. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampin resistance by use of on-demand, near-patient technology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:229–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hillemann D., Weizenegger M., Kubica T., Richter E., Niemann S. 2005. Use of the Genotype MTBDR assay for rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3699–3703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang W. L., Chen H. Y., Kuo Y. M., Jou R. 2009. Performance assessment of the GenoType MTBDRplus test and DNA sequencing in detection of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2520–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kent P. T., Kubica G. P. 1985. Public health mycobacteriology. A guide for a level III laboratory. Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Makinen J., Marttila H. J., Marjamaki M., Viljanen M. K., Soini H. 2006. Comparison of two commercially available DNA line probe assays for detection of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:350–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marlowe E. M., et al. 2011. Evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in respiratory specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1621–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mani C., Selvakumar N., Narayanan S., Narayanan P. R. 2001. Mutations in the rpoB gene of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2987–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moure R., et al. 2011. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and rifampin resistance in smear-negative clinical samples by use of an integrated real-time PCR method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1137–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raja S., et al. 2005. Technology for automated, rapid, and quantitative PCR or reverse transcription-PCR clinical testing. Clin. Chem. 51:882–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Telenti A., et al. 1993. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet 341:647–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tuberculosis Service. 2009. Tuberculosis report in Turkey. Ministry of Health, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]