Abstract

We report the first known case of syphilis with simultaneous manifestations of proctitis, gastritis, and hepatitis. The diagnosis of syphilitic proctitis and gastritis was established by the demonstration of spirochetes with anti-Treponema pallidum antibody staining in biopsy specimens. Unusual manifestations of secondary syphilis completely resolved after 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy.

CASE REPORT

A 28-year-old homosexual Japanese man was referred to our hospital for assessment of an abnormal liver function test and circumferential thickening of the rectal wall. The patient presented with a 1-month history of diarrhea, painful defecation, and occasional hematochezia and a 1-week history of mild upper abdominal discomfort. He had been diagnosed with secondary syphilis in a local clinic a week prior to admission based on the serological test for syphilis (STS), the Treponema pallidum hemagglutination test (TPHA), and the classical skin lesion. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) screening test was negative. Initial laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell (WBC) count, 7,300 cells/μl (normal range, 3,900 to 9,800 cells/μl); red blood cell (RBC) count, 473 × 104 cells/μl (range, 410 × 104 to 530 × 104 cells/μl); hemoglobin (Hb) level, 13.8 g/dl (range, 13.5 to 17.6 g/dl); platelet count, 29.5 × 104 platelets/dl (range, 12 × 104 to 36 × 104 platelets/dl); total serum protein (TP), 7.6 g/dl (range, 6.5 to 8.0 g/dl); aminotransferase (AST) level, 62 IU/liter (range, 8 to 38 IU/liter); alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, 74 IU/liter (range, 4 to 44 IU/liter); lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, 175 mg/dl (range, 115 to 224 mg/dl); alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level, 486 IU/liter (range, 104 to 338 IU/liter); γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) level, 62 IU/liter (range, 16 to 73 IU/liter); fasting blood glucose (FBG) level, 84 mg/dl (range, 70 to 107 mg/dl); serological test for syphilis (STS) (latex agglutination assay) results, 155.94 Sysmex units (SU)/ml; Treponema pallidum hemagglutination test (TPHA) results, 1,814.50 SU/ml.

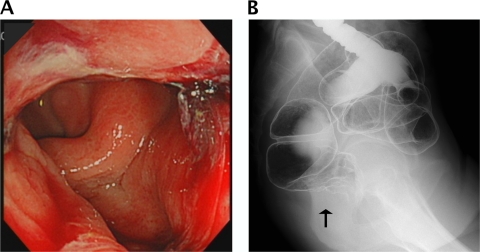

On admission, the patient's body temperature was 37.8°C. The general physical examination was basically normal except for bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy without pain and small, nonconfluent, erythematous, macular lesions on the trunk, back, arms, and face. The patient admitted to recent, unprotected, receptive anal intercourse. There were no detectable anal lesions, but rectal examination showed circumferential thickening of the rectal wall. The colonoscopy showed an indurated nodular mucosa around the rectal lumen, which initially suggested a submucosal tumor. A barium enema showed similar findings (Fig. 1A and B). Histologic findings of the rectal mucosa revealed severe inflammatory cell infiltration, predominantly by plasma cells. No malignant cells were identified. Immunostaining of rectal biopsy specimens with anti-Treponema pallidum polyclonal antibodies identified numerous spirochetes, and the diagnosis of syphilitic proctitis was confirmed.

Fig. 1.

(A) Sigmoidoscopy findings indicating multiple chancres and indurated nodular mucosa located on the wall of the lower rectum. (B) Barium enema results showing circumferential thickening of the lower rectal wall and multiple nodular mucosa.

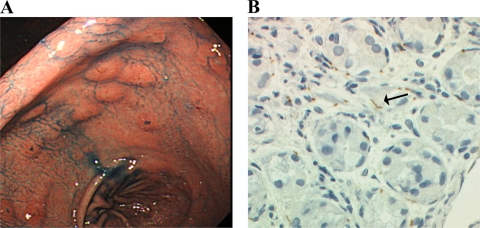

The patient had been complaining of upper abdomen discomfort. His antecedent medical records, including stomach disease, were not remarkable. The gastroduodenoscopy showed multiple erosive lesions in the whole gastric mucosa, and numerous spirochetes were identified by immunostaining the biopsy specimens (Fig. 2A and B). Histologic examination of the mucosa showed mild infiltration of neutrophils with superficial necrosis and fibropurulent exudates. There was no evidence of carcinoma, lymphoma, or Helicobacter pylori infection.

Fig. 2.

(A) Gastroscopic findings demonstrating multiple erosive lesions in the whole gastric mucosa (indigo carmine dye contrast). (B) A gastric biopsy specimen with antibody staining showing numerous brown stained spirochetes (arrow) in the interstitium (Treponema pallidum polyclonal antibody stain). Magnification, ×400.

A liver function test at admission showed elevated AST (480 IU/liter), ALT (607 IU/liter), ALP (2,493 IU/liter), LDH (420 IU/liter), γ-GTP (774 IU/liter), and total bilirubin (TB) (1.1 mg/dl) levels. Acute viral hepatitis was initially suspected, but the following serologic markers of acute viral infection were all negative: IgM anti-hepatitis A virus (IgM-HAV), the hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg), the IgM anti-HBV core antigen (IgM-HBc), hepatitis C virus antibodies (HCV-Ab), IgM anti-hepatitis E virus (IgM-HEV), IgM anticytomegalovirus (IgM-CMV), and the IgM anti-viral capsid antigen of the Epstein-Barr virus (IgM-VCA EBV). On the other hand, serological markers for IgG-CMV, the IgG-VCA EBV, and the EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) were all positive, suggesting that the patient was previously infected with CMV and EBV. HBV DNA, HCV RNA, and HIV RNA were not detected. The results for both the antimitochondrial M2 antibody and anti-smooth muscle antibodies were negative. The immunoglobulin levels, including the IgE level, were all normal. The antinuclear antibody (ANA) was positive at a titer of 1:40 (speckled pattern). However, autoimmune hepatitis was ruled out by other laboratory data and did not fulfill the criteria proposed by the international autoimmune hepatitis group (9). Abdominal ultrasonography did not reveal any evidence of chronic liver diseases. There was no history of alcohol abuse, intravenous drug abuse, oral illicit drug use, or smoking. The levels of ALP, γ-GTP, and TP were progressively elevated to 5,358 IU/liter, 1,103 IU/liter, and 1.9 mg/dl, respectively, 4 days after admission. A liver biopsy was not done because the patient's consent was not obtained. Although the etiology of the liver enzyme abnormalities remained unclear, alternative causes of hepatic damage were excluded and syphilitic hepatitis was strongly suspected. There were no cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities, including the results of the STS and TPHA. Oral administration with 2.25 g/day amoxicillin hydrate (AMOX) was initiated according to the guidelines proposed by The Japanese Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases. A Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, consisting of fever and skin rash deterioration, developed 6 h after the first oral administration of AMOX but resolved spontaneously in 24 h. The liver function tests improved gradually and became normal after 4 weeks of AMOX administration. The patient's fever resolved promptly, and his skin lesions disappeared in a few days. Circumferential thickening of the rectal wall and upper abdominal discomfort were completely resolved; in addition, the STS results decreased to 5.28 SU/ml 2 months after the initiation of AMOX.

T. pallidum, the etiologic agent of syphilis, is known to affect a wide variety of organs. Involvements of the skin, genital organs, retinas, and central nervous system are well described, but occasionally, unusual manifestations, such as gastrointestinal lesions and liver and renal dysfunction, can occur. We highlight T. pallidum here as an important but often unrecognized agent that could involve the rectum, stomach, and liver simultaneously. In a search of the MEDLINE database since 1960, this is the first case report which manifested three unusual complications, proctitis, gastritis, and hepatitis, in secondary syphilis. Syphilitic proctitis is rarely reported but is being recognized more frequently due to the recently increased incidence of syphilis among men who have sex with men (MSM). A retrospective review of clinical proctitis in MSM showed that syphilis was found in 2% of clinical patients presenting with rectal symptoms (6). Anorectal primary syphilis is easily overlooked because of the absence of anal lesions in some cases. In addition, it is difficult to diagnose because clinical manifestations of syphilitic proctitis have been shown to mimic amoebiasis, Crohn's disease, malignant lymphoma, or carcinoma (4).

Syphilitic gastritis is found in less than 1% of patients with syphilis and is seldom reported (4). The gastroduodenoscopy features described in previous case reports are multiple erosive or ulcerative lesions in the whole gastric mucosa. Endoscopic and microscopic findings can mimic gastric cancer or lymphoma (7). To make a definitive diagnosis of syphilitic gastritis and proctitis, it is necessary to identify T. pallidum histologically. Immunohistochemistry staining with anti-T. pallidum polyclonal antibodies can be used to detect T. pallidum in tissue, as it was in the present case. Recently, better sensitivity and a more rapid diagnosis of gastric syphilis were achieved by using real-time PCR (3).

Hepatitis, as well as proctitis and gastritis, is a rare complication of syphilis. Liver dysfunction occurring in early syphilis presents a diagnostic challenge. Clinical manifestations of syphilitic hepatitis described in previous reports showed that levels of alkaline phosphatase were disproportionately elevated relative to those of bilirubin and transaminases (2). These features are consistent with those of our case. Mullick et al. proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of acute syphilitic hepatitis (10): abnormal liver enzyme levels indicating hepatic involvement, serological evidence for syphilis with a positive TPHA titer in conjunction with an acute clinical presentation consistent with secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of hepatic injury, and improvements in liver enzyme levels with an appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Our case met all of these criteria, and we therefore attributed this patient's liver dysfunction to the involvement of T. pallidum even though a liver biopsy was not performed. A liver biopsy specimen is likely to have a lower yield for detection of T. pallidum than a biopsy specimen of gastrointestinal tissue. The majority of reported cases since 1975 failed to reveal treponemes in liver biopsy specimens (1, 2, 8, 11). Although the precise mechanism involving three different organs in this case remains unclear, we believe that the relationship between proctitis and hepatitis is related to the venous drainage pathway from the rectal area into the portal system. This postulation is supported by the fact that syphilitic hepatitis occurs often in conjunction with syphilitic proctitis (5) and is seen frequently in persons who engage in anal intercourse (2).

Syphilitic involvement of the stomach, rectum, and liver is easily overlooked and has not been described in the modern literature to our knowledge. These are all reversible conditions, and appropriate antibiotic treatment results in rapid resolution. Therefore, the diagnosis of these complications is important to prevent progression to a severe condition and to avoid unnecessary investigations. Clinicians should bear in mind the possibility of syphilitic involvement in patients at risk for sexually transmitted diseases who present with either gastrointestinal discomfort or liver dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kei Ouchi for his comments on drafts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Agrawal N. M., Sassaris M., Brooks B., Akdamar K., Hunter F. 1982. The liver in secondary syphilis. South. Med. J. 75: 1136–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campisi D., Whitcomb C. 1979. Liver disease in early syphilis. Arch. Intern. Med. 139: 365–366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen C.-Y., et al. 2006. Diagnosis of gastric syphilis by direct immunofluorescence staining and real-time PCR testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44: 3452–3456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cooley R. N., Childers J. H. 1960. Acquired syphilis of the stomach. Report of two cases. Gastroenterology 39: 201–207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crum-Cianflone N., Weekes J., Bavaro M. 2009. Syphilitic hepatitis among HIV-infected patients. Int. J. STD AIDS 20: 278–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamlyn E., Taylor C. 2006. Sexually transmitted proctitis. Postgrad. Med. J. 82: 733–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim K., et al. 2009. Clinicopathological features of syphilitic gastritis in Korean patients. Pathol. Int. 59: 884–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mandache C., et al. 2006. A forgotten aetiology of acute hepatitis in immunocompetent patient: syphilitic infection. J. Intern. Med. 259: 214–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manns M. P., et al. 2010. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 51: 2193–2213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mullick C. J., et al. 2004. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: a report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39: e100–e105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schlossberg D. 1987. Syphilitic hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 82: 552–553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]