Abstract

The degQ gene of Bacillus subtilis (natto), encoding a small peptide of 46 amino acids, is essential for the synthesis of extracellular poly-gamma-glutamate (γPGA). To elucidate the role of DegQ in γPGA synthesis, we knocked out the degQ gene in Bacillus subtilis (natto) and screened for suppressor mutations that restored γPGA synthesis in the absence of DegQ. Suppressor mutations were found in degS, the receptor kinase gene of the DegS-DegU two-component system. Recombinant DegS-His6 mutant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli cells and subjected to an in vitro phosphorylation assay. Compared with the wild type, mutant DegS-His6 proteins showed higher levels of autophosphorylation (R208Q, M195I, L248F, and D250N), reduced autodephosphorylation (D250N), reduced phosphatase activity toward DegU, or a reduced ability to stimulate the autodephosphorylation activity of DegU (R208Q, D249G, M195I, L248F, and D250N) and stabilized DegU in the phosphorylated form. These mutant DegS proteins mimic the effect of DegQ on wild-type DegSU in vitro. Interestingly, DegQ stabilizes phosphorylated DegS only in the presence of DegU, indicating a complex interaction of these three proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular poly-gamma-glutamate (γPGA) is a glutamate polymer linked through a gamma-peptide bond produced outside the cells by bacilli, including Bacillus subtilis, B. licheniformis, and B. anthracis, and Staphylococcus epidermidis (4). It acts as a nutrient reservoir to prevent starvation in the stationary phase and as a barrier against bacteriophage or phagocytotic attack by the host immune system (4, 12, 14, 16). Microbial functions that are not essential for the life cycle under laboratory conditions but that are required for survival in the natural environment are sometimes lost in domesticated laboratory strains. The loss of the ability to synthesize γPGA in a laboratory strain of B. subtilis is an example of such an event, and a mutation in degQ is involved in it (30).

degQ function was characterized mainly through studies of the γPGA-negative laboratory lineage B. subtilis 168. degQ encodes a small peptide of 46 amino acids, and it is a pleiotropic regulator of degradation enzymes, including alkaline protease, α-amylase, and levansucrase (1). The expression of degQ is dependent on comA, the global transcriptional regulator in the stationary phase, and is strongly induced under dense-cell conditions (18). The regulation of these exoenzymes by degQ requires the presence of the degS-degU operon that comprises a two-component system (17, 18). The sensor histidine kinase DegS has four activities: it acts as a self-kinase (autophosphorylation of His189), a self-phosphatase (autodephosphorylation), a phosphotransferase (phosphorylation of Asp56 of DegU), and a phosphatase (dephosphorylation of DegU) (5, 6, 15, 20, 31). Exoenzyme expression is controlled directly by DegU, a DNA-binding protein, and DegU phosphorylation by DegS (DegU-Pi) enhances it (25, 29, 34). A recent study reported that DegQ stimulates phosphate transfer from phosphorylated DegS (DegS-Pi) to DegU (15). Thus, genetic and biochemical analyses of degQ suggest that it transmits the cell density signal from ComA to DegS-DegU, but the mechanism by which DegS controls the balance of kinase and phosphatase activities remains unknown (21).

degQ is essential for the synthesis of γPGA and nonribosomal peptides (iturin A and plipastatin) in undomesticated B. subtilis strains (30, 33). The γPGA-negative (γPGA−) phenotype of B. subtilis laboratory strain 168 can be explained partly by a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at position −10 in the promoter region of degQ (30). The laboratory strain has C at the −10 position. Due to this SNP, the level of expression of degQ is reduced to about 1/50 of that of strains that have T instead of C, whereas undomesticated γPGA-positive (γPGA+) strains possess the SNP T, leading to degQ overproduction (18, 30).

B. subtilis (natto) is a γPGA+ strain used for the fermentation of natto (a soybean fermented food) and the industrial production of γPGA for various purposes (9, 28, 36). In B. subtilis (natto), γPGA synthesis is directed by an operon, pgsBCA (also referred to as capBCA or ywsC ywtAB) (3, 4). PgsB possesses ATPase activity and is considered to have a catalytic center for the polymerization of glutamate (35). The functions of PgsA and the hydrophobic protein PgsC are obscure. The expression of the pgs operon is dependent on degQ, degU, and comA (13, 30, 32), suggesting that it is regulated by the cell density signaling pathway, as in the case of the degradation enzyme genes of the laboratory strain. However, how DegQ controlled γPGA synthesis was unclear (27, 30).

To identify regulatory genes for γPGA synthesis, we knocked out degQ in B. subtilis (natto) and screened for suppressor mutants whose γPGA production recovered in the absence of degQ. The suppressor mutations were classified into two groups based on phenotypes of γPGA synthesis, genetic competence, and genetic linkage to the degS-degU locus. Among the nine suppressor mutants, six had mutations in degS, the sensor kinase gene of the DegS-DegU two-component system. These mutant DegS proteins were purified and examined for autophosphorylation, dephosphorylation, and phosphotransfer to DegU in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. subtilis was cultured in GSP medium containing 1.5% glucose, 1.5% l-glutamic acid, and 1.5% BBL Phytone peptone (Becton Dickinson and Company, Cockeysville, MD) for γPGA production (22) and in LB for enzyme production. LB containing 1% sucrose was used for levansucrase production. These media were supplied with the following antibiotics when required: ampicillin (100 μg/ml for Escherichia coli), kanamycin (20 μg/ml for E. coli and 10 μg/ml for B. subtilis), spectinomycin (30 μg/ml for E. coli and 300 μg/ml for B. subtilis), erythromycin (1 μg/ml for B. subtilis), and lincomycin (12.5 μg/ml for B. subtilis). E. coli and B. subtilis were transformed as described elsewhere previously (2, 10) and selected on LB agar plates with appropriate antibiotics.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. subtilis | ||

| NAFM5 | bio; γPGA+ | 12 |

| NAFM73 | NAFM5 derivative; degQ::Ermr; γPGA− | This study |

| NAFM731-NAFM739 | NAFM73 derivative; degQ::Ermrsup1-9; γPGA+ | This study |

| NAFM114 | NAFM5 derivative; yvyE::Spcr | This study |

| NAFM104 | NAFM5 derivative; degU::Kmr | 13 |

| NAFM65 | NAFM5 derivative; comP::Spcr | 14 |

| BS168 | trpC2; laboratory strain | 2 |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− λ−endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 recA gyrA relA1 Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 deoR [φ80Δ(lacZ)M15] | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| BL21(DE3) | For recombinant protein expression | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDG646 | ColE1 replicon; Apr Ermr | 8 |

| PDG780 | ColE1 replicon; Apr Kmr | 8 |

| pDG1726 | ColE1 replicon; Apr Spcr | 8 |

| pET22b(+) | Apr; for recombinant protein expression | Novagen |

| pCR2.1 | ColE1 replicon; Apr Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pNAG401 | HindIII-HindIII degSU fragment subcloned into pUC118 | 13 |

| pNAG413 | pCR2.1 harboring yvyE::Spcr | This study |

| pG-KJE8 | Chaperon-expressing plasmid | TaKaRa-Bio |

γPGA analysis.

γPGA produced by B. subtilis cells was analyzed as described previously (22).

Disruption of degQ in B. subtilis (natto).

NAFM73 (degQ::Ermr) was constructed as follows. Genomic DNA fragments from nucleotides (nt) −810 to +67 (5′ fragment) and from nt +81 to +920 (3′ fragment) of degQ (translation start point at position +1) were amplified with the following primer pairs with BamHI sites (underlined): 5′-AATGATTGCGGTCCTCTGACCACCACCG-3′ (corresponding to nt −810 to −786) and 5′-GGATCCTCGTTTCTTTAATATCAAGTTCGAGTCGG-3′ (complementary to nt +39 to +67) as well as 5′-GGATCCAAACATTAACAAAAGCATTGATCAACTCG-3′ (corresponding to nt +81 to +109) and 5′-AGTCATTATAGTTAGGGTAATAAAGTCC-3′ (complementary to nt +893 to +920). The two fragments were introduced into the HincII site of pUC118, and nucleotide sequences were verified. The BamHI-EcoRI degQ 3′ fragment was ligated into the degQ 5′ fragment at BamHI (the BamHI site of the vector was removed in advance), and an erythromycin-resistant cassette (Ermr) (as a BamHI fragment from pDG646) (8) was then inserted into the BamHI site created in degQ. This plasmid was linearized by ScaI digestion and used to transform wild-type NAFM5. The correct disruption of degQ by double-crossover recombination was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Mutagenesis.

We mutagenized B. subtilis NAFM73 (degQ::Ermr) cells with ethylmethanesulfonate and screened for γPGA+ colonies on GSP plates. Approximately 40,000 colonies were visually screened.

Genetic linkage of suppressor mutations to the degS locus.

The nucleotide sequence of the yvyE-degS-degU genomic DNA fragment (2.7 kbp) of B. subtilis (natto) was previously determined (GenBank accession no. AB176706). The linkage to the degS locus was examined by mapping the mutation with the neighboring yvyE gene as a marker. The genome segment of yvyE was amplified with primer pair yvyE-dn (5′-CACGCGGAATGCTCAGCATTTTC-3′ [complementary to nt +981 to +1009 of yvyE]) and yvyE-up (5′-TATGTCGAATTATAAGAAAGAATGCG-3′ [corresponding to nt −155 to −128 of yvyE]) and cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). The spectinomycin cassette from pDG1726 as the HincII-EcoRV fragment was inserted into the SnaBI site at nt +524 of yvyE. This plasmid (pNAG413) was introduced into B. subtilis NAFM5 to generate NAFM114 (yvyE::Spcr). Suppressor mutants were transformed with genomic DNA of NAFM114. At least 20 spectinomycin-resistant transformants were selected and characterized.

Determination and confirmation of suppressor mutations.

The strategy for mapping the suppressor mutations and primers used is diagramed in Fig. 1. To identify the suppressor mutations in NAFM731, NAFM732, NAFM733, NAFM735, NAFM737, and NAFM739, we amplified the 2.8-kb genomic DNA covering the degS-degU region using primers degSU-sq1 (5′-TAAGCTTCCGTTCTACAACACC-3′ [upstream of the degS gene from nt −620 to −598]) and degSU-sq6 (5′-AAGCTTTTCCAGTCCAACTCAATA-3′ [complementary to nt +908 to +930 of degU]) and then determined the nucleotide sequences of the amplified DNA fragments directly. To confirm that the mutations identified in degS can restore the defect of NAFM73 (degQ::Ermr), we introduced mutated alleles of the degS gene into NAFM73 using yvyE::Spcr as a marker. Initially, NAFM731, NAFM732, NAFM733, NAFM735, NAFM737, and NAFM 739 were transformed with pNAG413 (see above). Next, 3.8-kb fragments covering yvyE::Spcr and the mutated degS of transformants were amplified by PCR using primers yvyE-dn and degS3′XhoI (5′-CTCGAGAAGAGATAACGGAACCTTAATCATAATA-3′) (Fig. 1) and introduced into strain NAFM73 by transformation. The degS mutations in the obtained transformants were confirmed by direct nucleotide sequencing.

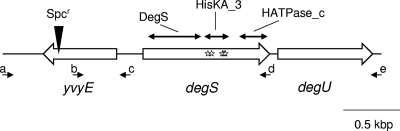

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the yvyE-degS-degU region. The yvyE, degS, and degU genes are drawn as open arrows, and the Spcr marker introduced into yvyE is indicated by a solid triangle. Solid arrows indicate oligonucleotide primers used for the mapping of suppressor mutations: a, yvyE-dn; b, degSU-sq1; c, yvyE-up; d, degS3′XhoI; e, degSU-sq6. Stars in degS indicate the mutation points identified. Functional domains of DegS, Pfam DegS (amino acid residues 12 to 170), Pfam HisKA_3 (residues 180 to 248), and Pfam HATPase_c (residues 289 to 384) (21), are indicated by thin arrows.

Enzyme assay.

Alkaline protease, amylase, γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), and levansucrase were assayed as described previously (1, 14, 23), with a minor modification. For levansucrase assays, cells were grown in LB medium containing 1% sucrose.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins.

Primer pairs DegS5′NdeI (5′-CATATGAATAAAACAAAGATGGATTCCAAAG-3′ [nt +4 to +28 of degS] [the NdeI site is underlined]) and DegS3′XhoI (5′-CTCGAGAAGAGATAACGGAACCTTAATCATAATA-3′ [complementary to nt +1127 to +1155 of degS] [the XhoI site is underlined]), DegU5′NdeI (5′-CATATGACTAAAGTAAACATTGTTATTATCGAC-3′ [nt +4 to +30 of degU] [the NdeI site is underlined]) and DegU3′XhoI (5′-CTCGAGTCTCATTTCTACCCAGCCATTTTTAATG-3′ [complementary to nt +657 to +684 of degU] [the XhoI site is underlined]), and degQ-5′NdeI (5′-CATATGGAAAAGAAACTTGAAGAAGTAAA-3′ [nt +1 to +26 of degQ] [the NdeI site is underlined]) and degQ-3′XhoI (5′-CTCGAGTCACGAAATTTTCATTGCATAATTG-3′ [complementary to nt +116 to +141 of degQ] [the XhoI site is underlined]) were used to amplify the coding region of degS, degU, and degQ. Genomic DNAs of the suppressor mutants were used to amplify mutated degS genes. Amplified fragments were cloned into the NdeI-XhoI site of an expression plasmid, pET22b(+) (Novagen). E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) cells harboring a molecular-chaperon -expressing plasmid (pG-KJE8; TaKaRa-Bio, Tokyo, Japan) were used as a host for expressing DegS and DegU. pG-KJE8 has dnaK-dnaJ-grpE under an l-arabinose-inducible promoter and groES-groEL under a tetracycline-inducible promoter. DegQ was expressed as a soluble form by using E. coli BL21(DE3) cells without pG-KJE8. E. coli cells transformed with the expression vector were propagated at 26°C for DegS and at 30°C for DegU and DegQ in 500 ml of LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to 0.05 mM for induction (for expressing DegS and DegU, 5 ng/ml tetracycline and 0.5 mg/ml l-arabinose were added together). Cells were further incubated overnight for protein expression. Cells were harvested and washed with buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and cell pellets were stored at −80°C until use.

Wild-type and mutant DegS-His6 proteins were purified as follows. Cells were resuspended in 7 ml of buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and disrupted by sonication (Sonifier 250; Branson, Danbury, CT). Cell debris and the insoluble fraction were removed by ultracentrifugation (200,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C). The supernatant was used as a soluble fraction, dialyzed against buffer B containing 10 mM imidazole, and loaded onto a Ni affinity column (HisTrap HP; GE Healthcare) equilibrated with the same buffer. DegS-His6 was eluted by a linear gradient of imidazole (10 to 300 mM). Purified DegS-His6 was dialyzed against a dialysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM CaCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol). For comparison, wild-type DegS-His6 was also prepared from the insoluble inclusion body formed in E. coli host cells without the chaperon plasmid pG-KJE8 by using urea for solubilization as described previously (15).

DegU-His6 was purified as follows. E. coli cells were resuspended in 7 ml buffer C (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol). The soluble fraction was prepared, and DegU-His6 was purified by Ni affinity column chromatography as described previously (11). Purified DegU-His6 was dialyzed against a dialysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 200 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM CaCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol).

DegQ was purified as follows. E. coli cells were suspended in 100 ml of buffer D (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and disrupted with a French press (SLM-Aminco, Rochester, NY) at 15.7 MPa. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was subjected to precipitation with streptomycin to remove nucleic acids (the final concentration of streptomycin was 7 mg/ml, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at 4°C). The soluble fraction obtained by ultracentrifugation (100,000× g for 60 min at 4°C) was dialyzed in buffer E (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgSO4) and further fractionated by ammonium sulfate precipitation (60% saturation). The precipitate was dissolved in 40 ml of buffer E, dialyzed again in buffer E, and then loaded onto a HiPrep-16/10 DEAE column (column volume, 20 ml; GE Healthcare). The column was washed with buffer E. DegQ was eluted in wash fractions, as judged by SDS-PAGE. Peaks were collected and concentrated by use of Centriprep-10 (Amicon) and subjected to gel filtration chromatography (Superose 12; GE Healthcare). DegQ was eluted with buffer E containing 100 mM NaCl.

Phosphorylation of DegS-His6.

DegS-His6 was autophosphorylated in vitro with [γ-32P]ATP (220 TBq/mmol; GE Healthcare) as reported previously (6), with modifications. Purified DegS-His6 (0.5 μM) was incubated with or without DegQ (3.0 μM) in 160 μl of phosphorylation buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM CaCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) containing 10 μM [γ-32P]ATP (4.4 TBq/mmol) at 25°C. Aliquots (15 μl) were taken at the indicated times, and the reaction was stopped by adding SDS-PAGE sampling buffer to the mixture and heating at 95°C for 2 min. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Dephosphorylation of DegS-His6.

DegS-His6 (1.0 μM) was phosphorylated for 45 min as described above. An equal volume of the phosphorylation buffer containing an excess amount of cold ATP (2 mM) and, if necessary, DegQ (6.0 μM) was added to the reaction mixture, and the mixture was further incubated at 25°C. Aliquots (15 μl) were taken at the indicated times, and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Transfer of phosphate from DegS-His6 to DegU-His6.

DegS-His6 (1.0 μM) was autophosphorylated as described above for 45 min. An equal volume of the phosphorylation buffer containing DegU-His6 (1.0 μM) and cold ATP (2 mM) was added to the reaction mixture, and the mixture was incubated at 25°C. Aliquots (15 μl) were taken at the indicated times, and samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Stability of the phosphorylated DegS-DegU two-component system.

DegS-His6 (1.0 μM) and DegU-His6 (1.0 μM) were incubated in phosphorylation buffer containing 10 μM [γ-32P]ATP (4.4 TBq/mmol) at 25°C for 45 min. An equal volume of phosphorylation buffer containing an excess amount of cold ATP (2 mM) was added to the reaction mixture, and the mixture was further incubated at 25°C. Aliquots (15 μl) were taken at the indicated times, and samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. If necessary, DegQ (final concentration, 3.0 μM) was added to the chase mixture.

The developed X-ray films were scanned, and phosphorylated protein spots were quantified by use of NIH Image free software (version 1.62).

DNA manipulation.

Plasmid DNAs of E. coli and B. subtilis were extracted by the alkali lysis method (24) and subjected to restriction analysis. For DNA sequencing and plasmid construction, plasmid DNA was purified from E. coli cells by use of a Flex-Prep system (GE Healthcare). Other DNA methods were previously described (24). The nucleotide sequence was determined by use of an ABI310 DNA sequencer and a BigDye Terminator sequencing kit, v.3.1 (Applied Biosystems). Chemicals, if not otherwise specified, were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals.

RESULTS

Structure and disruption of degQ in B. subtilis (natto).

The amino acid sequence of DegQ of B. subtilis (natto) deduced from the nucleotide sequence was 100% identical to DegQ of laboratory strain B. subtilis 168. We then compared the regulatory and promoter regions of degQ. The expression of degQ is regulated by four distinct systems, DegS-DegU, ComP-ComA, catabolite repression, and regulation by phosphate in the laboratory strain (18). Target sequences of these regulatory systems are located upstream of degQ. They were identical between B. subtilis (natto) and B. subtilis 168 except for the SNP at the −10 position in the promoter. The nucleotide at position −10 was T, which confers a “hyperpromoter” in B. subtilis (natto) (GenBank accession no. AB039951) (18). The sequence profile of degQ was confirmed by whole-genome sequence data reported recently (24).

B. subtilis (natto) produced higher quantities of degradation enzymes (alkaline protease, GGT, and levansucrase), except for amylase, than laboratory strain 168 (Table 2), and the level of genetic competency of B. subtilis (natto) was far lower than that of strain 168 (Table 2). The disruption of degQ abolished γPGA synthesis in B. subtilis (natto), and the production of degradation enzymes was also downregulated, in accordance with data from previous studies (18, 30) (Table 2). In contrast, the genetic competency was improved by the degQ disruption, although it remained lower than that of B. subtilis 168 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exoenzyme and γPGA production and transformability of the γPGA+ suppressor mutants derived from NAFM73 (degQ::Ermr)a

| Strain | Relevant mutation | GGT concn (mU/ml) | Amylase concn (U/ml) | Alkaline protease concn (U/ml) | γPGA concn (mg/ml) | Levansucrase concn (mU/ml) | Competencyb (no. of Spcr transformants obtained [10−8]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS168 | WT (laboratory strain) | <0.01 | 2400 | 8.2 | <0.01 | <2 | 1,218 |

| NAFM5 | WT (natto strain) | 0.5 | 218.0 | 50.2 | 11.2 | 173.1 | 11 |

| NAFM65 | comP::Spcr | <0.01 | <10 | 2.0 | <0.01 | 37.4 | NT |

| NAFM73 | degQ::Ermr | 0.1 | <10 | 3.0 | <0.01 | 4.9 | 116 |

| NAFM104 | degU::Kmr | 0.02 | <10 | 1.6 | <0.01 | <2 | NT |

| NAFM114 | yvyE::Spcr | 0.3 | NT | 26.3 | 13.3 | 165.1 | NT |

| Group 1 | |||||||

| NAFM731 | degQ::Ermrsup1 | 1.4 | 765.8 | 73.6 | 11.2 | 312.4 | 28 |

| NAFM732 | degQ::Ermrsup2 | 1.2 | 442.8 | 45.9 | 2.0 | 367.0 | 26 |

| NAFM733 | degQ::Ermrsup3 | 1.0 | 93.1 | 39.6 | 0.1 | 144.5 | 25 |

| NAFM735 | degQ::Ermrsup5 | 2.0 | 2696.2 | 60.4 | 14.0 | 324.7 | 27 |

| NAFM737 | degQ::Ermrsup7 | 1.0 | 1213.1 | 50.9 | 8.5 | 415.8 | 25 |

| NAFM739 | degQ::Ermrsup9 | 2.0 | 370.8 | 64.0 | 10.0 | 496.3 | 26 |

| Group 2 | |||||||

| NAFM734 | degQ::Ermrsup4 | 0.2 | <10 | 8.5 | 0.3 | 142.8 | 110 |

| NAFM736 | degQ::Ermrsup6 | 0.2 | <10 | 14.8 | 0.7 | 111.9 | 135 |

| NAFM738 | degQ::Ermrsup8 | 0.3 | <10 | 13.1 | 0.4 | 81.2 | 186 |

Values are averages of three measurements. Bacillus subtilis cells were grown in LB medium or LB medium containing 1% sucrose (for levansucrase). Precultures (1% volume) were inoculated into fresh medium, and enzyme activities in the supernatants were measured after 24 h of incubation with vigorous shaking. NT, not tested; WT, wild type.

Competency was calculated from the number of Spcr transformants obtained with 1 μg DNA per total viable cells. Genomic DNA of NAFM90 (ggt::Spcr) (13) was employed for the transformation.

Characterization of suppressor mutants.

We mutagenized NAFM73 (degQ::Ermr) and screened for suppressor mutants with a restored ability to produce γPGA by the observation of colonies on GSP agar plates. Among ca. 40,000 colonies, 9 produced slimy material. The slimy material was confirmed to be γPGA by amino acid analysis, gel filtration high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and digestion with a γPGA-specific enzyme (7; data not shown). The γPGA+ suppressor mutants made clear halos around their colonies on LB agar containing 1% skim milk, indicating that the suppressor mutations also restored protease production (data not shown). These suppressor mutants (NAFM731 to NAFM739) grew normally in LB and GSP liquid media and were characterized further for γPGA production, degradation enzyme synthesis, and genetic competency (Table 2). Suppressor mutants (NAFM731, NAFM732, NAFM735, NAFM737, and NAFM739) that were able to produce γPGA at the wild-type level produced the degradation enzymes in amounts comparable to or higher than those of the wild-type strain (Table 2). Strains NAFM733, NAFM734, NAFM736, and NAFM738, which showed partially (1 to 6%) restored γPGA production, had lower levels of degradation enzymes, except for NAFM733 (Table 2). Amylase activity was not detected in NAFM734, NAFM736, and NAFM738. The suppressor mutants that fully regained degradation enzymes and γPGA production were less competent in genetic transformation than parental strain NAFM73, whereas those that acquired low-level γPGA and degradation enzyme productivities were still as competent as NAFM73, except for NAFM733 (Table 2). Two types of suppressor mutations appeared to occur.

Identification of suppressor mutations.

The regulation of degradation enzymes and genetic competence by degQ requires the presence of degS and degU (18). To determine whether mutation sites occurred in degS or degU, we replaced the degS-degU region of suppressor mutants with that of the wild type. For this purpose, the spectinomycin cassette was inserted into the SnaBI site of yvyE (the 5′-adjacent gene of degS) in wild-type NAFM5, generating NAFM114 (yvyE::Spcr) (Fig. 1). NAFM114 produced comparable amounts of γPGA and levansucrase, and about 50% of the amount of protease and GGT, compared to the amounts produced by the wild type (Table 2). Suppressor mutants were transformed with genomic DNA of NAFM114 (yvyE::Spcr), and at least 20 transformants that were resistant to spectinomycin and erythromycin were selected. All transformants derived from NAFM734, NAFM736, and NAFM738 produced γPGA (data not shown). All transformants derived from NAFM732, NAFM735, NAFM737, and NAFM739 lost the ability to produce γPGA, and approximately 85% of transformants derived from NAFM731 and NAFM733 did not produce γPGA (data not shown). The tight linkage of the Spcr and γPGA-negative phenotypes meant that the corresponding suppressor mutations occurred near the yvyE locus. Thus, suppressor mutants were classified into two groups (group 1, NAFM731, NAFM732, NAFM733, NAFM735, NAFM737, and NAFM739; group 2, NAFM734, NAFM736, and NAFM738) according to the genetic linkage to the degS-degU locus.

The nucleotide sequence of the degSU promoter region of wild-type B. subtilis (natto) NAFM5 was identical to the corresponding region of strain 168 (GenBank accession no. AB176706). The coding sequences of degS and degU had several base changes, but no amino acid alterations in degS and only one amino acid alteration (Met208 to Ile) in degU were observed for strain NAFM5. The 2.8-kb degS-degU regions of the suppressor mutants were amplified by PCR. The nucleotide sequences of the amplified DNA fragments revealed that the group 1 suppressor mutants NAFM731, NAFM732, NAFM733, NAFM735, NAFM737, and NAFM739 have one mutation in the degS gene: G to A at position +585 (NAFM733), G to A at position +623 (NAFM731), C to T at position +733 (NAFM737), C to T at position +742 (NAFM735), A to G at position +746 (NAFM732), and G to A at position +748 (NAFM739), respectively (numbers are relative to the translation start site [position +1] of degS). These nucleotide changes caused the amino acid substitutions M195I, R208Q, P245S, L248F, D249G, and D250N. No mutation was observed for degU. No mutation was found in the 2.8-kb degS-degU regions of group 2 suppressor mutants.

To confirm that the mutations identified in degS can restore the defect of strain NAFM73, the mutated degS genes of group 1 suppressor mutants were introduced into NAFM73 using yvyE::Spcr as a marker (Fig. 1). The group 1 mutants were transformed with pNAG413 to disrupt yvyE by the Spcr marker. Fragments of 3.8 kb covering the yvyE::Spcr and degS suppressor alleles were amplified and then introduced into strain NAFM73 by transformation. Mutations introduced into degS of the transformants were confirmed by direct nucleotide sequencing. The transformants with degS mutant alleles were γPGA+ and had phenotypes very similar to those of the original suppressor mutants (data not shown), confirming that mutations in degS are responsible for the restored γPGA synthesis.

In order to know whether suppressor mutants can bypass the degU function to synthesize γPGA, degU of suppressor mutants of both groups 1 and 2 was disrupted by a kanamycin-resistant cassette as described previously (13). The disruption of degU abolished γPGA production in all the suppressor mutants.

Recombinant protein expression and purification.

Recombinant DegS-His6 expressed in conventional E. coli BL21(DE3) host cells absolutely formed inclusion bodies, as described previously (15, 31). Although refolded DegS-His6 purified from the inclusion body exhibited autophosphorylation activity in vitro, as described previously (15) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), the refolding process cannot be monitored precisely, which makes comprehensive comparisons of mutant proteins very difficult. To overcome this difficulty, soluble recombinant DegS-His6 was prepared by using the host E. coli strain harboring a chaperon plasmid (pG-KJE8) and by purification under high-salt conditions (500 mM NaCl) (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Purified soluble DegS-His6 was precipitated under low-salt conditions, and DegS-His6 of the inclusion body was not solubilized with the high-salt buffer. Soluble wild-type DegS-His6 showed higher levels of autophosphorylation than the refolded one in vitro (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material); the amount of radioactive phosphate incorporated into DegS-His6 gradually increased during 45 min of incubation and then decreased in both the soluble and the refolded forms of DegS-His6, but much more phosphate (about 1.7-fold at 45 min of incubation) was incorporated into the soluble DegS-His6 than into the refolded DegS-His6 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

We purified soluble mutant DegS-His6 proteins (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material) and subjected them to further analyses, but the P245S mutant protein was produced only in the form of an inclusion body in E. coli cells even in the presence of pG-KJE8. The P245S mutant protein was eliminated from in vitro analyses.

DegU-His6 expressed as a soluble form in the chaperon harboring E. coli host cells was purified as described in Materials and Methods (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material). High-salt conditions were not required for DegU-His6. DegQ was expressed in a soluble form in the conventional E. coli host without the chaperon plasmid and purified (see Fig. S2D in the supplemental material). The histidine tag was not employed in the preparation of DegQ. The addition of the histidine tag to the C terminus of DegQ resulted in the formation of an inclusion body of DegQ-His6 (data not shown).

DegS autophosphorylation and dephosphorylation.

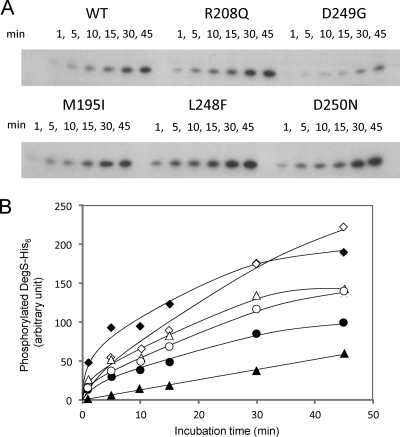

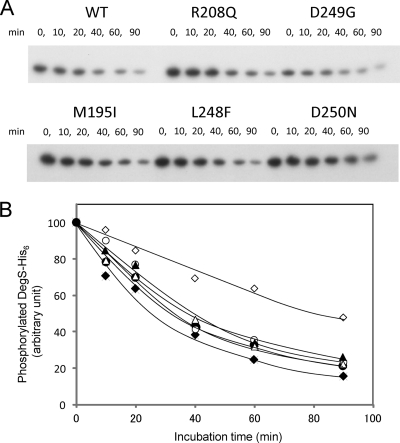

Except for D249G, four mutant proteins, R208Q, M195I, L248F, and D250N, showed higher levels of autophosphorylation activity than the wild type (Fig. 2). By chasing incorporated radioactive phosphate, DegS dephosphorylation was examined. Wild-type DegS-Pi was dephosphorylated gradually, and about 80% of the incorporated phosphate was released in 90 min (Fig. 3). Mutant proteins showed essentially similar dephosphorylation kinetics; however, D250N showed slower dephosphorylation than the others (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Autophosphorylation of wild-type and mutant DegS-His6 proteins. (A) DegS-His6 expressed in the chaperon-expressing E. coli host was purified and incubated with [γ-32P]ATP for the indicated periods at 25°C. Aliquots of samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Spots of phosphorylated DegS-His6 were quantified by use of NIH Image software (version 1.62). Closed circles, wild type (WT); open circles, R208Q mutation; closed triangles, D249G mutation; open triangles, M195I mutation; closed squares, L248F mutation; open squares, D250N mutation. Values are expressed as a percentage of the values for the wild type at 45 min.

Fig. 3.

Dephosphorylation of DegS-His6. (A) DegS-His6 was incubated together with [γ-32P]ATP at 25°C for 45 min as described in Materials and Methods. An excess amount of cold ATP was added to the reaction mixture, and the phosphorylation of DegS-His6 was chased for 90 min at 25°C. Portions were taken at the indicated times and were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Spots of phosphorylated DegS-His6 were quantified by use of NIH Image software (version 1. 62). Closed circles, wild type; open circles, R208Q mutation; closed triangles, D249G mutation; open triangles, M195I mutation; closed squares, L248F mutation; open squares, D250N mutation. Values are expressed as percentages of the initial values.

Transfer of phosphate from DegS to DegU.

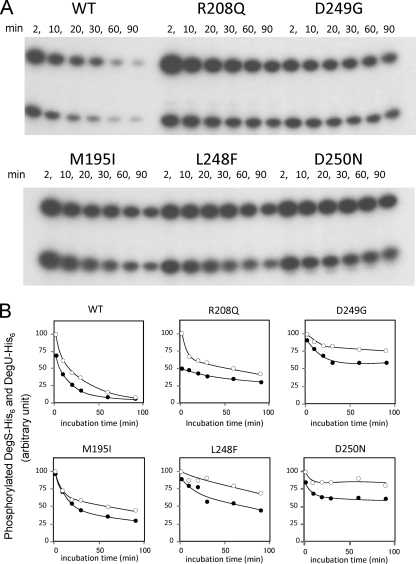

Wild-type and mutant DegS-His6 proteins were autophosphorylated for 45 min. The transfer of phosphate was chased by the addition of DegU-His6 and a 100× excess amount of cold ATP (final concentration, 1 mM). For the wild type, DegU-Pi was observed abundantly at 2 min of incubation, and the levels then gradually decreased (Fig. 4). Only faint signals of phosphate moieties of DegS-His6 and DegU-His6 were observed after 90 min of incubation (Fig. 4). Evidently, the transfer reaction proceeded quickly within 2 min, and we could not observe the kinetics of the transfer reaction itself by our hands. Rather, the results observed meant that there was dephosphorylation and turnover of the phosphate moiety.

Fig. 4.

Phosphotransfer from DegS-His6 to DegU-His6. (A) Wild-type and mutant DegS-His6 proteins were autophosphorylated for 45 min as described in Materials and Methods. DegU-His6 and excess cold ATP were added to the reaction mixture, and the mixture was further incubated at 25°C for the indicated times. Aliquots were taken from the reaction mixture and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Spots of phosphorylated DegU-His6 and DegS-His6 were quantified by NIH Image free software (version 1.62). Closed circles, DegU-His6; open circles, DegS-His6. Values are expressed as percentages of values for phosphorylated DegS-His6 at 2 min for each sample.

In contrast to the wild type, DegS-Pi and DegU-Pi were relatively stable in the mutants (Fig. 4). About 40 to 80% of the phosphate moiety of mutant DegS-His6 remained after 90 min of incubation. Furthermore, in the presence of mutant DegS, the dephosphorylation of DegU-Pi became slow. The dephosphorylation profiles of DegU-Pi followed those of mutant DegS-His6 (Fig. 4B).

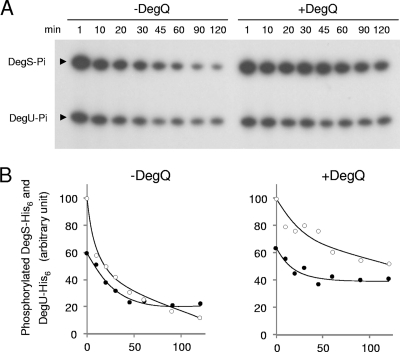

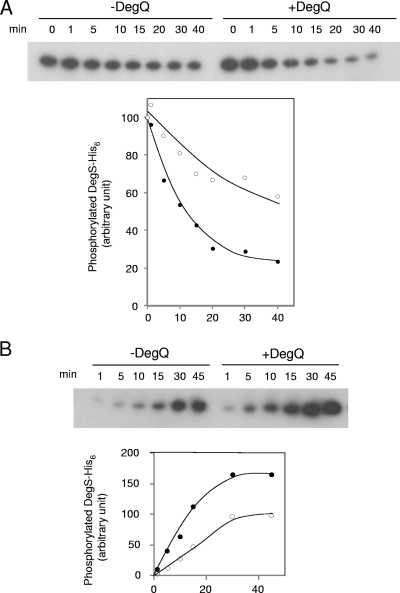

Effect of DegQ on phosphorelay.

The dephosphorylation of mutant DegS-His6 in the phosphate transfer assay was slower than that of the wild type (Fig. 4), which suggested that DegQ might stabilize the DegS-DegU two-component system in the phosphorylated state. We experimentally examined this in vitro. Wild-type DegS-His6 and DegU-His6 were incubated for 45 min for the phosphotransfer reaction. An excess amount of cold ATP was then added, and the incorporated phosphate was chased in the presence and absence of DegQ. In the presence of DegQ, the radioactive phosphate moieties of DegS-His6 and DegU-His6 were liberated more slowly than in the absence of DegQ (Fig. 5A). After 2 h of chasing, more than 50% and 65% of labeled 32P were still bound to DegS-His6 and DegU-His6, respectively (Fig. 5B). Thus, DegQ stabilized the phosphorylation of the DegS-DegU two-component system. In the absence of DegU-His6, the dephosphorylation of DegS-His6 was not stabilized by DegQ but rather was enhanced (Fig. 6A), and the autophosphorylation of DegS-His6 was apparently enhanced by DegQ (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 5.

Stability of phosphorylation in the DegS-DegU two-component system. (A) Wild-type DegS-His6 and DegU-His6 were incubated together with [γ-32P]ATP for 45 min at 25°C. An excess amount of cold ATP was added to the reaction mixture, and the phosphorylation of DegS-His6 and DegU-His6 was chased for 90 min in the presence and absence of DegQ at 25°C. Portions were taken at the indicated times and were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Spots of phosphorylated DegU-His6 and DegS-His6 were quantified by use of NIH Image software (version 1.62). Closed circles, DegU-His6; open circles, DegS-His6. Values are expressed as percentages of the values of phosphorylated DegS-His6 at 1 min.

Fig. 6.

Dephosphorylation and autophosphorylation of DegS-His6 in the presence of DegQ. (A) Wild-type DegS-His6 was incubated together with [γ-32P]ATP for 45 min at 25°C. An excess amount of cold ATP was added to the reaction mixture, and phosphorylated DegS-His6 was chased in the presence (right panel) (closed circles) and absence (left panel) (open circles) of DegQ for 40 min at 25°C. Portions were taken at the indicated times and were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Wild-type DegS-His6 was incubated together with [γ-32P]ATP for 45 min in the presence (right panel) (closed circles) and absence (left panel) (open circles) of DegQ at 25°C. Portions were taken at the indicated times and were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Spots of phosphorylated DegS-His6 were quantified as described in Materials and Methods and are plotted below the film images. Values are expressed as percentages of the initial value (for dephosphorylation) or the value at 45 min of incubation without DegQ (for autophosphorylation).

DISCUSSION

DegS consists of three domains, belonging to Pfam DegS (amino acid residues 12 to 170), Pfam HisKA_3 (residues 180 to 248), and Pfam HATPase_c (residues 289 to 384) (21). The suppressor mutations were accumulated in the HisKA_3 domain, a phosphoacceptor domain containing His189 for autophosphorylation (Fig. 1).

The identified suppressor mutations in degS resulted in the amino acid substitutions M195I, R208Q, P245S, L248F, D249G, and D250N. P245S was eliminated from in vitro experiments because it was not produced in the soluble fraction. The Pro245 residue might be important for the proper folding of DegS in E. coli cells. Except for D249G, mutant proteins had higher levels of autophosphorylation activity than the wild-type proteins (Fig. 2). The dephosphorylation profiles of mutant proteins were essentially the same as that of the wild type, except for D250N, which liberated phosphate more slowly than the others (Fig. 3). We were not able to analyze the phosphotransfer kinetics precisely, but wild-type and mutant DegS proteins appeared to have comparable phosphotransfer activities toward DegU-His6 (Fig. 4). However, mutant DegS-His6 proteins exhibited distinct behaviors in the dephosphorylation of DegU-Pi. In wild-type DegS, DegU-Pi was not stable due to the phosphatase activity toward DegU-Pi or the autodephosphorylation activity of DegU on itself (Fig. 4) (19, 31), but DegU-Pi phosphorylated by the mutant DegS proteins became stable (Fig. 4). For example, D249G autophosphorylated less than the wild type, but DegU-His6 phosphorylated by D249G was far more stable than that phosphorylated by the wild type. In the presense of DegU, these DegS mutants also appeared to have reduced rates of autodephosphorylation (Fig. 4). Since DegU-Pi is assumed to be a direct activator of the pgs operon that directs γPGA synthesis (26), we concluded that the suppression of the loss of degQ can be explained by the increased amount of DegU-Pi in the mutant cells. The lower genetic competency of the group 1 suppressor mutants than that of parental strain NAFM73 also suggests that the amount of unphosphorylated DegU was reduced in the cells because unphosphorylated DegU promotes genetic competency (21).

The behavior of DegS mutant proteins in vitro implied that DegQ may stabilize DegU-Pi in wild-type cells. This idea was reinforced by experimental results; in the presence of DegQ, the wild-type DegS-DegU two-component system remained in the phosphorylated state for a longer time than in the absence of DegQ (Fig. 5). On the other hand, DegQ did not stabilize DegS-Pi in the absence of DegU-His6; rather, the turnover of the phosphate moiety of DegS-His6 was facilitated by DegQ (Fig. 6). DegQ appears to act on DegS differently depending on the presence of DegU.

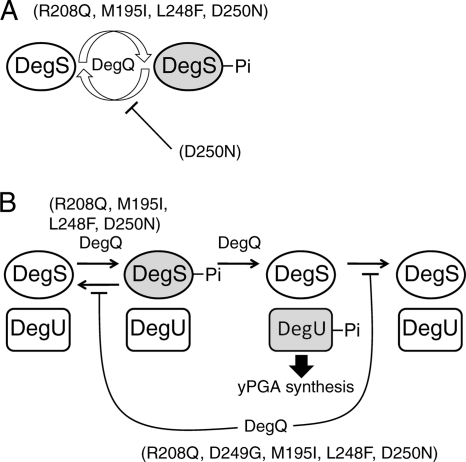

These observations suggest that DegQ increases the cellular amount of DegS-Pi by stimulating the autophosphorylation of DegS through a direct interaction and stabilizes the DegU-Pi by suppressing the DegS phosphatase activity toward DegU-Pi or by reducing the DegU autodephosphorylation activity in the ternary complex of DegS, DegU, and DegQ and that DegS mutations mimic the effect of DegQ on wild-type DegS and DegU (Fig. 7). Among the suppressor mutants, NAFM733 (D249G) produced γPGA to 0.1 mg/ml, which was lower than the amount produced by other suppressor mutants (Table 2). The D249G mutation stabilized DegU-Pi as much as the other DegS mutations (Fig. 4), but the level of autophosphorylation activity of the D249G mutation was lower than those of the other DegS mutations and even lower than that of the wild type (Fig. 2). Probably, both the enhancement of autophosphorylation and the suppression of the phosphatase activity of DegS are required for the full recovery of γPGA production.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representations of action models showing the character of mutated DegS proteins and how DegQ and the DegS-DegU two-component system regulate γPGA synthesis. (A) Binary reaction between DegQ and DegS. (B) Ternary reaction of DegQ, DegS, and DegU. Arrows indicate the direction of the reaction and positive regulation by DegQ and DegS mutations. Perpendicular bars indicate negative regulation. Phosphorylated proteins are shaded.

The genetic interaction between degQ and the HisKA_3 domain of degS implies that the phosphoacceptor domain might be a site of the direct interaction between DegQ and DegS. The DegS domain (residues 12 to 170), with an unknown function, is another candidate site regulating the interaction. Although the physiological significance is obscure, Ser76 in this domain is phosphorylated in vivo, and YbdM was proposed previously to be a kinase responsible for Ser76 phosphorylation (11). The expression of the pgs operon is regulated not only by cell density but also by nutritional signals from the environment (13). It will be interesting to examine if the phosphorylation of Ser76 modulates the interaction between DegQ and DegS responding to such signals. This awaits further experimental elucidation.

Two mutated alleles of degS (degS100 and degS200) that confer the hyperproduction of protease in laboratory strain 168 were reported previously (31). The dephosphorylation of DegU-Pi that was phosphorylated by DegS100 and DegS200 was slower than that phosphorylated by wild-type DegS (31), which resembles the case of the DegS mutant proteins that we characterized in this study. However, it is uncertain whether degS100 and degS200 are included in the 6 alleles that we found, because the sites of the degS100 and degS200 mutations were not determined.

Contradictory results showing that DegS-Pi is stable in vitro and that DegQ affected neither the autophosphorylation nor the dephosphorylation of DegS-His6 were reported previously (15). The discrepancy may be explained by the difference in procedures for recombinant protein preparation. In the previous report, DegS-His6 was prepared from the inclusion body by solubilization with 8 M urea and subsequent refolding, but a significant part of the refolded DegS-His6 appeared to remain inactive. The amount of incorporated radioactive phosphate in refolded DegS-His6 was less than 40% of the amount of soluble DegS-His6 prepared in this study (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In the refolding method, unfolded DegS-His6 or the remaining urea, even at a low concentration, might disturb the interaction between DegS-His6 and DegQ. DegQ stimulated phosphotransfer from DegS-His6 to DegU-His6 in the previous study (15). The transfer reaction proceeded rapidly in our hands, and we were not able to observe the transfer kinetic itself. Probably, DegQ acts both in phosphate transferring to DegU and in stabilizing DegU-Pi.

Mukai et al. reported previously that DegR stabilizes DegU-Pi in vitro (19). The DegS used in their experiment was not homogeneously purified and supplied as a soluble cell extract prepared from a DegS-overproducing B. subtilis strain. This experimental procedure was a device created for the monitoring of the dephosphorylation of DegS-Pi and DegU-Pi (19); thus, our results confirmed that the preparation of DegS in the soluble form is important for the study of the phosphorylation of the DegS-DegU two-component system. degR encodes a small protein of 60 amino acids, and multiple copies of degR stimulated alkaline protease gene (aprE) expression in vivo (19). DegQ and DegR are not homologous in amino acid sequence, but the in vivo and in vitro behaviors of DegR and DegQ are similar. However, degR stimulated the expression of aprE only when it was on a multicopy plasmid, and the disruption of degQ severely impaired aprE expression (Table 2). Perhaps, degR is poorly expressed in cells under the physiological conditions studied.

The degS-degU two-component system is widely conserved in Bacillus species (21). B. amyloliquefaciens, B. licheniformis, and B. pumilus possess DegQ proteins with 91.3% (42/46 residues), 69.6% (32/46), and 69.6% (32/46) amino acid identities to B. subtilis DegQ, respectively. Their DegS proteins are 95.1% (366/385), 89.6% (345/385), and 86.2% (332/385) identical to that of B. subtilis, respectively. The DegU proteins of B. amyloliquefaciens, B. licheniformis, and B. pumilus are highly homologous to B. subtilis DegU, with amino acid identities of 100% (229/229), 98.7% (226/229), and 99.1% (227/229), respectively. The divergence in DegQ and DegS implies coevolution and their direct interaction. A DegQ-homologous protein was not found in the genomes of B. clausii and B. halodurans, although they have DegS homologues (55.3% and 53.6% identical to DegS of B. subtilis, respectively). These bacteria might have functionally redundant proteins instead of DegQ or do not integrate the cell density signal to the DegS-DegU two-component system.

The group 2 suppressor mutants NAFM734, NAFM736, and NAFM738 partially recovered the ability to produce γPGA (Table 2). Their levels of alkaline protease activities were lower than that of wild-type B. subtilis (natto) but about 2 times higher than that of B. subtilis 168. The loci of the group 2 mutations are unclear due to the lack of genetic markers in the strain used in this study. This awaits further experimental elucidation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan. T.-H.D. is a UNU-Kirin fellow.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 30 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amory A., Kunst F., Aubert E., Klier A., Rapoport G. 1987. Characterization of the sacQ genes from Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 169: 324–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ashikaga S., Nanamiya H., Ohashi Y., Kawamura F. 2000. Natural genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis natto OK2. J. Bacteriol. 182: 2411–2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ashiuchi M., Soda K., Misono H. 1999. A poly-gamma-glutamate synthetic system of Bacillus subtilis IFO 3336: gene cloning and biochemical analysis of poly-gamma-glutamate produced by Escherichia coli clone cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 263: 6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Candela T., Fouet A. 2006. Poly-gamma-glutamate in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 60: 1091–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dahl M. K., Msadek T., Kunst F., Rapoport G. 1991. Mutational analysis of the Bacillus subtilis DegU regulator and its phosphorylation by the DegS protein kinase. J. Bacteriol. 173: 2539–2547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dahl M. K., Msadek T., Kunst F., Rapoport G. 1992. The phosphorylation state of the DegU response regulator acts as a molecular switch allowing either degradative enzyme synthesis or expression of genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 14509–14514 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fujimoto Z., Shiga I., Itoh Y., Kimura K. 2009. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of poly-gamma-glutamate hydrolase from bacteriophage PhiNIT1. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 65: 913–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guérout-Fleury A. M., Shazand K., Frandsen N., Stragier P. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167: 335–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamano Y. (ed.). 2010. Microbiology monographs, vol. 15 Amino-acid homopolymers occurring in nature. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inoue H., Nojima H., Okayama H. 1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96: 23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jers C., Kobir A., Sondergaard E. O., Jensen P. R., Mijakovic I. 2011. Bacillus subtilis two-component system sensory kinase DegS is regulated by serine phosphorylation in its input domain. PLoS One 6: e14653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kimura K., Itoh Y. 2003. Characterization of poly-gamma-glutamate hydrolase encoded by a bacteriophage genome: possible role in phage infection of Bacillus subtilis encapsulated with poly-gamma-glutamate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69: 2491–2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kimura K., Tran L. S. P., Do T. H., Itoh Y. 2009. Expression of the pgsB encoding the poly-gamma-dl-glutamate synthetase of Bacillus subtilis (natto). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73: 1149–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kimura K., Tran L. S. P., Uchida I., Itoh Y. 2004. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis gamma-glutamyltransferase and its involvement in the degradation of capsule poly-gamma-glutamate. Microbiology 150: 4115–4123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kobayashi K. 2007. Gradual activation of the response regulator DegU controls serial expression of genes for flagellum formation and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 66: 395–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kocianova S., et al. 2005. Key role of poly-gamma-dl-glutamic acid in immune evasion and virulence of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Clin. Invest. 115: 688–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Msadek T., et al. 1990. Signal transduction pathway controlling synthesis of a class of degradative enzymes in Bacillus subtilis: expression of the regulatory genes and analysis of mutations in degS and degU. J. Bacteriol. 172: 824–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Msadek T., Kunst F., Klier A., Rapoport G. 1991. DegS-DegU and ComP-ComA modulator-effector pairs control expression of the Bacillus subtilis pleiotropic regulatory gene degQ. J. Bacteriol. 173: 2366–2377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mukai K., Kawata-Mukai M., Tanaka T. 1992. Stabilization of phosphorylated Bacillus subtilis DegU by DegR. J. Bacteriol. 174: 7954–7962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mukai K., Kawata M., Tanaka T. 1990. Isolation and phosphorylation of the Bacillus subtilis degS and degU gene products. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 20000–20006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murray E. J., Kiley T. B., Stanley-Wall N. R. 2009. A pivotal role for the response regulator DegU in controlling multicellular behaviour. Microbiology 155: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nagai T., Koguchi K., Itoh Y. 1997. Chemical analysis of poly-gamma-glutamic acid produced by plasmid-free Bacillus subtilis (natto): evidence that plasmids are not involved in poly-gamma-glutamic acid production. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 43: 139–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nicholson W. L., Setlow P. 1990. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth, p. 391–450In Harwood C. R., Cutting S. M. (ed.),Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, West Sussex, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nishito Y., et al. 2010. Whole genome assembly of a natto production strain Bacillus subtilis natto from very short read data. BMC Genomics 11: 243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogura M., Shimane K., Asai K., Ogasawara N., Tanaka T. 2003. Binding of response regulator DegU to the aprE promoter is inhibited by RapG, which is counteracted by extracellular PhrG in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 49: 1685–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ohsawa T., Tsukahara K., Ogura M. 2009. Bacillus subtilis response regulator DegU is a direct activator of pgsB transcription involved in gamma-poly-glutamic acid synthesis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73: 2096–2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Osera C., Amati G., Calvio C., Galizzi A. 2009. SwrAA activates poly-gamma-glutamate synthesis in addition to swarming in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 155: 2282–2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shih I. L., Van Y. T. 2001. The production of poly-(gamma-glutamic acid) from microorganisms and its various applications. Bioresour. Technol. 79: 207–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimane K., Ogura M. 2004. Mutational analysis of the helix-turn-helix region of Bacillus subtilis response regulator DegU, and identification of cis-acting sequences for DegU in the aprE and comK promoters. J. Biochem. 136: 387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stanley N. R., Lazazzera B. A. 2005. Defining the genetic differences between wild and domestic strains of Bacillus subtilis that affect poly-gamma-DL-glutamic acid production and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 57: 1143–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tanaka T., Kawata M., Mukai K. 1991. Altered phosphorylation of Bacillus subtilis DegU caused by single amino acid changes in DegS. J. Bacteriol. 173: 5507–5515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tran L. S., Nagai T., Itoh Y. 2000. Divergent structure of the ComQXPA quorum-sensing components: molecular basis of strain-specific communication mechanism in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 37: 1159–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsuge K., Ano T., Hirai M., Nakamura Y., Shoda M. 1999. The genes degQ, pps, and lpa-8 (sfp) are responsible for conversion of Bacillus subtilis 168 to plipastatin production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43: 2183–2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tsukahara K., Ogura M. 2008. Characterization of DegU-dependent expression of bpr in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 280: 8–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Urushibata Y., Tokuyama S., Tahara Y. 2002. Characterization of the Bacillus subtilis ywsC gene, involved in gamma-polyglutamic acid production. J. Bacteriol. 184: 337–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoshikawa T., et al. 2008. Development of amphiphilic gamma-PGA-nanoparticle based tumor vaccine: potential of the nanoparticulate cytosolic protein delivery carrier. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 366: 408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.