Abstract

In the presence of nitrate, N2O emission increased markedly from soybean roots inoculated with nosZ mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum, but not from soybean roots inoculated with a napA nosZ double mutant, indicating that B. japonicum bacteroids in soybean nodules are able to convert the exogenously supplied nitrate into N2O via a denitrification pathway.

TEXT

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a key atmospheric greenhouse effect gas that not only affects global warming but also leads to destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer (15). Agricultural land is one of the major sources of N2O (8, 12, 23). In particular, more N2O is emitted from agricultural fields with legume crops than from fields with nonlegume crops (5, 11). Kim et al. (10) found that N2O emission from fields with nodulating soybean was several times higher than that from fields with nonnodulating soybean at a flowering stage of soybean growth in the field, suggesting that nodulation enhanced N2O emission. On the other hand, Sameshima-Saito et al. (17) reported that soybean nodules can take up a low concentration of N2O from outside the nodules, equivalent to the natural concentration of N2O in the air (approximately 0.31 ppm) and that this uptake depends on the nosZ gene, which encodes N2O reductase in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Therefore, the N2O metabolism of nodulated soybean roots is complex, and the mechanism underlying N2O emission from soybean fields has not yet been identified.

Under field conditions, N fertilization generally increases the nitrate concentration in the soil solution (7). Thus, we hypothesized that the increased nitrate supply may lead to an increase in N2O emission from intact soybean root systems via a denitrification pathway in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a napA nosZ double mutant of B. japonicum USDA110; the wild-type (WT) versions of these genes encode dissimilatory nitrate reductase (3) and N2O reductase (17), respectively.

The bacterial strains and plasmids we used are listed in Table 1. Bradyrhizobium cells were grown at 30°C in HM salt medium supplemented with 0.1% arabinose and 0.025% (wt/vol) yeast extract (Difco, Detroit, MI) (18). HM medium was further supplemented with trace metals (HMM medium) for the denitrification assay (17). Escherichia coli cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (16). Antibiotics were added to the media: tetracycline (Tc) at 100 μg/ml, spectinomycin (Sp) at 100 μg/ml, streptomycin (Sm) at 100 μg/ml, kanamycin (Km) at 100 μg/ml, and polymyxin B at 50 μg/ml for B. japonicum and Tc at 15 μg/ml, Sp at 50 μg/ml, Sm at 50 μg/ml, Km at 50 μg/ml, and ampicillin (Ap) at 100 μg/ml for E. coli.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | ||

| USDA110 | Wild type, nosZ+ | 9 |

| USDA110 ΔnosZ::Tc | USDA110 derivative, nosZ::del/ins Tc cassette; Tcr | This study |

| USDA110 ΔnapA | USDA110 derivative, napA::Ω cassette; Spr Smr | This study |

| USDA110 ΔnapA ΔnosZ | USDA110 derivative, nosZ::del/ins Tc cassette Tcr; napA::Ω cassette Spr Smr | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | recA, cloning strain | Toyobo Inc. |

| Plasmids | ||

| pK18mob | Cloning vector, pMB1ori oriT Kmr | 21 |

| brp16565 | pUC18 carrying a 10.8-kb nap gene cluster | 9 |

| pRK2013 | ColE1 replicon carrying RK2 transfer gene; Kmr | 22 |

| p34S-Tc | Plasmid carrying 2.0-kb Tcr cassette; Tcr Apr | 4 |

| pHP45Ω | Plasmid carrying 2.1-kb Ω cassette; Spr Smr Apr | 14 |

| pK18mob-nap | pK18mob carrying 7.5-kb-HindIII fragment including nap gene cluster; Kmr | This study |

| pK18mob-ΔnapA::Ω | pK18mob carrying 9.5-kb fragment including nap gene cluster and Ω cassette; Kmr | This study |

| pTZ18RnosZ | pTZ18R carrying 4.0-kb-nosZ fragment; Apr | 17 |

| pK18mob-ΔnosZ::Tc | pK18mob carrying 4.6-kb fragment including nosZ and Tc cassette; Kmr Tcr | This study |

The resistance genes included the genes coding for resistance to ampicillin (Apr), kanamycin (Kmr), polymyxin B, streptomycin (Smr), spectinomycin (Spr), and tetracycline (Tcr).

Isolation of plasmids, DNA ligation, and transformation of E. coli were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (16). DNA preparation and Southern hybridization were carried out as described previously (20).

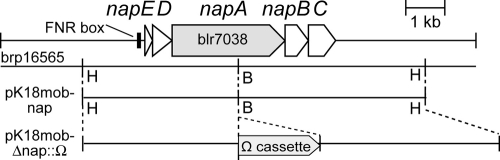

To construct a napA nosZ double mutant with different antibiotic markers, we reconstructed a nosZ single-deletion mutant in B. japonicum USDA110 using a Tc cassette. pK18mob-ΔnosZ::Tc was constructed using the Tc cassette from the previously created plasmid pTZ18RnosZ (17) and was subjected to triparental mating with a helper plasmid (pRK2013), resulting in USDA110 ΔnosZ::Tc (Table 1). For the napA mutation, a 7.5-kb DNA fragment carrying napEDABC was excised from HindIII-digested brp16565 (9) and inserted into the HindIII site of pK18mob (Fig. 1). A 2.0-kb Ω cassette derived from pHP45 (14) was then inserted at a BstPI site within napA of B. japonicum USDA110 (Fig. 1), resulting in pK18mob-ΔnapA::Ω (Fig. 1). Triparental mating with wild-type USDA110 and USDA110 ΔnosZ::Tc as recipients was conducted on HMM agar plates using pK18mob-ΔnapA::Ω and pRK2013, resulting in USDA110 ΔnapA and USDA110 ΔnapA ΔnosZ, respectively (Table 1). Double-crossover events were verified by Southern hybridization.

Fig. 1.

Construction of the napA insertion mutant. Cloned fragments in pK18mob-nap and pK18mob-ΔnapA::Ω are shown alongside the physical map of the nap gene cluster of B. japonicum USDA110. H, HindIII site; B, BstPI site. The 7.5-kb HindIII fragment containing the napEDABC genes was cloned into pK18mob, resulting in pK18mob-nap. After BstPI digestion and the blunt-end reaction, the Ω cassette was inserted into the BstPI site in napA, resulting in pK18mob-ΔnapA::Ω. By triparental mating using pK18mob-ΔnapA::Ω as a donor, USDA110 ΔnapA and USDA110 ΔnapA ΔnosZ were constructed from wild-type USDA110 and USDA110 ΔnosZ::Tc, respectively (see the text for details).

To confirm the denitrification capability of the mutants in culture, we measured the end products (N2O and N2) and the substrate (nitrate), as described previously (18, 19). Briefly, the aerobically grown cells (70 μl) were anaerobically incubated in HMM medium supplemented with 2 mM 15N-KNO3 (99.6 atom%) at 30°C for 7 days in a test tube (15 ml of broth with a 19-ml gas phase). The 15N2 and 15N2O in the gas phase and 15N-nitrate in the liquid phase were determined after incubation for 7 days.

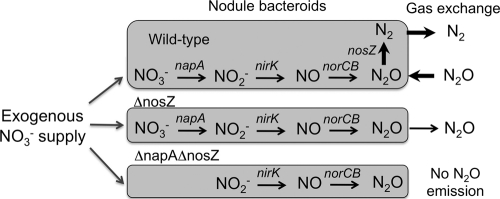

We germinated surface-sterilized soybean seeds (Glycine max cv. Enrei), and transplanted them into Leonard jars (17). We used cell suspensions of the wild-type and mutant strains of B. japonicum USDA110 (1 ml) for inoculation at 1 × 107 cells per seed. Plants were grown for 25 days in an LH200 growth chamber at 25°C with a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle (Nippon Medical & Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan). A nitrogen-free nutrient solution was periodically supplied to the jars (13). The whole root system of the soybean plant was inserted into a 51-ml test tube (19.4 mm in diameter by 176 mm in height) containing 20 ml of nitrogen-free nutrient solution (13) in the presence or absence of 5 mM potassium nitrate (Fig. 2). The test tube was then sealed with a silicone rubber stopper equipped with a gas sampling port and a hole for the plant's stem that was sealed with silicon gum after insertion of the plant. This setup enclosed the nodulated root system of intact soybeans in the test tube, leaving the aerial parts in the open air (Fig. 2). The N2O concentration of the gas phase in the chamber was monitored using a GC-14BPsE gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an electron capture detector and tandem-packed columns of Porapak N and Porapak Q (Shimadzu), as described previously (17).

Fig. 2.

Closed-test-tube hydroponic system used for measurements of N2O emission and uptake by the nodulated roots of intact soybean plants.

Free-living cells of the three mutants constructed in this work (Table 1) were examined in the denitrification assay (Table 2). The end product of wild-type USDA110 was N2, whereas that of USDA110 ΔnosZ::Tc was N2O. Both strains consumed all NO3−. Thus, USDA110 ΔnosZ::Tc lost the ability to reduce N2O as a result of Tc cassette insertion into the partially deleted nosZ gene (Table 2), which is similar to previous results with USDA110 ΔnosZ (17). USDA110 ΔnapA and USDA110 ΔnapA ΔnosZ did not consume NO3− and produced no N2O and no N2 (Table 2), indicating that they had lost the ability to reduce nitrate as a result of the Ω cassette insertion into napA (Fig. 1). Although cassette insertion often has a polar effect on downstream genes, such effect does not alter the interpretation because the downstream genes encode products for the same enzymatic processes (Fig. 1) (17).

Table 2.

Denitrification capability of B. japonicum mutants constructed in this work

| Strain or condition | Amt of end product (μmol/15 ml culture)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NO3− | N2O | N2 | |

| USDA110 (WT) | <0.1 | <0.1 | 32.2 |

| USDA110 ΔnosZ::Tc | <0.1 | 28.0 | <0.1 |

| USDA110 ΔnapA | 28.0 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| USDA110 ΔnapA ΔnosZ | 28.7 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Uninoculatedb | 28.5 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

Gray shading indicates the major end product (N2O and N2) or a high level of substrate (NO3−). Values are expressed as means of duplicate determinations.

“Uninoculated” refers to medium that was not inoculated with B. japonicum cells.

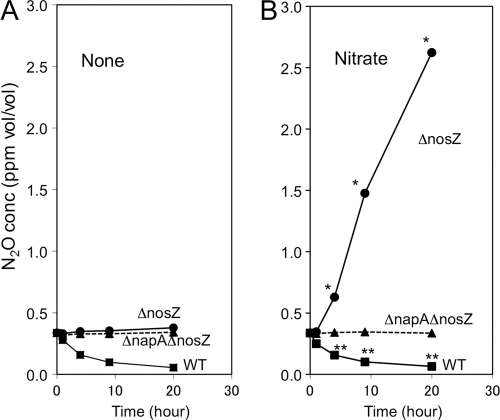

After soybean plants inoculated with wild-type USDA110 (WT), USDA110ΔnosZ::Tc (ΔnosZ), or USDA110 ΔnapA ΔnosZ (ΔnapA ΔnosZ) were established in the closed-root-system chambers containing air in the absence or presence of 5 mM potassium nitrate in hydroponic solution (Fig. 2), the N2O concentration was periodically monitored (Fig. 3). In the absence of nitrate (Fig. 3A), the soybean roots nodulated by the ΔnosZ and ΔnapA ΔnosZ strains showed no change in the N2O concentration in air, whereas the roots nodulated by wild-type strain USDA110 showed a continuous decrease in the N2O concentration, as was reported previously (17). In the presence of nitrate (Fig. 3B), the roots nodulated by the ΔnosZ strain emitted N2O, whereas the roots nodulated by the ΔnapA ΔnosZ mutant showed no change in the N2O concentration. Both mutants (ΔnosZ and ΔnapA ΔnosZ) differed only in whether they possessed the napA mutation in a common nosZ background (Table 1), and their differences in N2O emission from the nodulated roots were statistically significant (Fig. 3B). Therefore, we conclude that the wild-type napA gene is required for N2O emission from soybean roots nodulated by B. japonicum lacking the wild-type nosZ gene in the presence of nitrate.

Fig. 3.

N2O emission and uptake in the closed-root-chamber system (Fig. 2) by soybean nodules formed with the wild-type (WT), ΔnosZ mutant, or ΔnapA ΔnosZ double mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110 in the absence (A) and presence (B) of nitrate (5 mM KNO3). Asterisks indicate a significant difference in the N2O concentration from that of the napA nosZ double mutant at P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.01 (**) (t test, triplicate determination). Uninoculated soybean roots showed no emission and no uptake of N2O (data not shown), which was identical to the N2O profile of soybeans inoculated with the ΔnapA ΔnosZ double mutant.

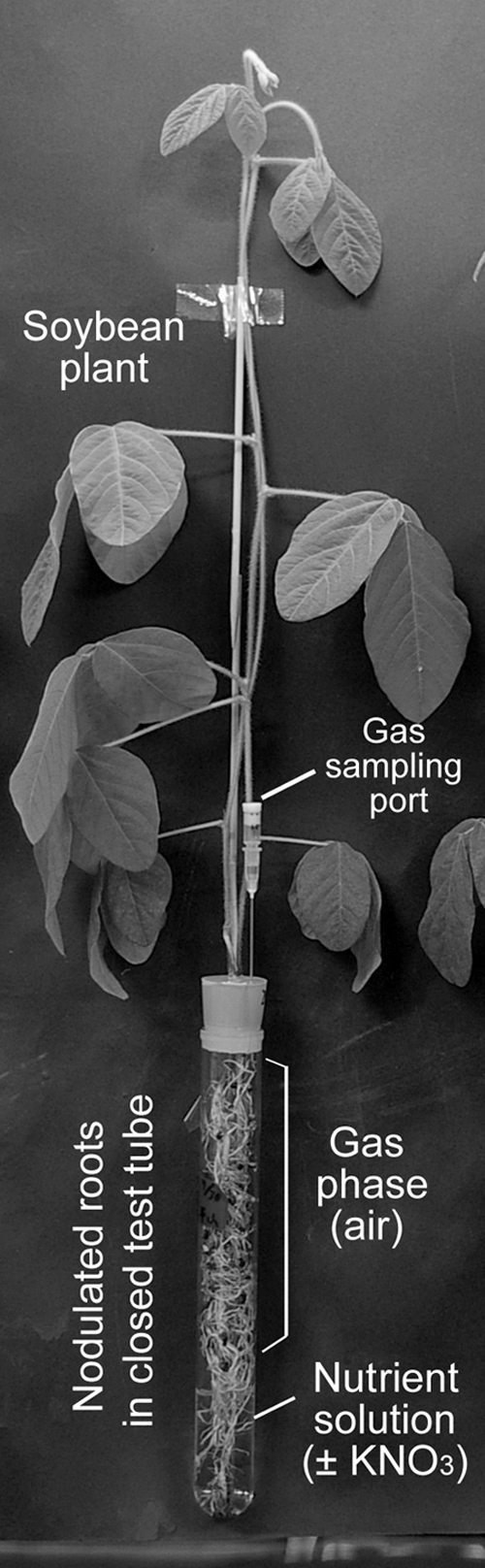

The napA gene encodes nitrate reductase, which catalyzes the first step in denitrification (NO3− → NO2− → NO → N2O → N2) in B. japonicum USDA110 (Fig. 4), and free-living cells of the napA mutant lost the capability to reduce nitrate (Table 2). Our results strongly suggest that endosymbiotic cells of B. japonicum that lack the wild-type nosZ gene in soybean nodules can convert exogenously supplied nitrate into N2O via their denitrification pathway (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of nitrate-dependent N2O emission from soybean nodules formed by the wild-type (WT) strain, the ΔnosZ mutant, and the ΔnapA ΔnosZ double mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. napA, nirK, norCB, and nosZ are structural genes coding for periplasmic nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, nitric oxide reductase, and nitrous oxide reductase, respectively, in B. japonicum USDA110 (1).

Natural nosZ-negative populations of B. japonicum, which lack nosZ and N2O reductase activity, are often dominant in soybean fields (19, 20). Therefore, if nosZ-negative populations of B. japonicum are dominant in soybean fields and if nitrate concentrations in the soil solution increase as a result of high levels of N fertilization or high soil N availability, N2O could be emitted from the nodulated soybean roots. Indeed, the variable in field experiments that best explained cumulative N2O emission during the whole soybean growing season was the soil nitrate level (2).

It is very surprising that root systems nodulated by wild-type USDA110 decreased the atmospheric N2O concentration (approximately 0.3 ppm) in the presence of nitrate (Fig. 3B). This result suggests that N2O reductase activity overcame any N2O production that resulted from the added nitrate (Fig. 4). Therefore, these results suggest that there is high potential to reduce N2O emissions by nosZ-carrying strains of B. japonicum to mitigate N2O emission from soybean rhizosphere (17). Recently, N2O reduction by nosZ-carrying inoculants was shown in soil-filled pots planted with soybean (6).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by BRAIN, by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (PMI-0002), and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (23248052) and for Challenging Exploratory Research (23658057) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bedmar E. J., Robles E. F., Delgado M. J. 2005. The complete denitrification pathway of the symbiotic, nitrogen-fixing bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:141–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ciampitti I. A., Ciarlo E. A. 2008. Nitrous oxide emissions from soil during soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) crop phenological stages and stubble decomposition period. Biol. Fertil. Soils 44:581–588 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delgado M. J., Bonnard N., Tresierra-Ayala A., Bedmar E. J., Muller P. 2003. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum napEDABC genes encoding the periplasmic nitrate reductase are essential for nitrate respiration. Microbiology 149:3395–3403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dennis J. J., Zylstra G. J. 1998. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of Gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2710–2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duxbury J. M., Bouldin D. R., Terry R. E., Tate R. L. 1982. Emissions of nitrous oxide from soils. Nature 298:462–464 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Henault C., Revellin C. 2011. Inoculants of leguminous crops for mitigating soil emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide. Plant Soil [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1007/s11104-011-0820-0 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ikeda S., et al. 2010. Community shifts of soybean stem-associated bacteria responding to different nodulation phenotypes and N levels. ISME J. 4:315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inaba S., et al. 2009. Nitrous oxide emissions and microbial community in the rhizosphere of nodulated soybeans during the late growth period. Microbes Environ. 24:64–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaneko T., et al. 2002. Complete genomic sequence of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. DNA Res. 9:189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim Y., et al. 2005. NO and N2O emissions from fields in the different nodulated genotypes of soybean. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 74:427–430 (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mori A., Honjito M., Kondo H., Matsunami H., Scholefield D. 2005. Effects of plant species on CH4 and N2O fluxes from a volcanic grassland soil in Nasu, Japan. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 51:19–27 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Okabe S., et al. 2010. A great leap forward in microbial ecology. Microbes Environ. 25:230–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okazaki S., Sugawara M., Minamisawa K. 2004. Bradyrhizobium elkanii rtxC gene is required for expression of symbiotic phenotypes in the final step of rhizobitoxine biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:535–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prentki P., Krisch H. M. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ravishankara A. R. J. S., Daniel, Portmann R. W. 2009. Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326:123–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sameshima-Saito R., et al. 2006. Symbiotic Bradyrhizobium japonicum reduces N2O surrounding the soybean root system via nitrous oxide reductase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2526–2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sameshima-Saito R., Chiba K., Minamisawa K. 2004. New method of denitrification analysis of Bradyrhizobium field isolates by gas chromatographic determination of 15N-labeled N2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2886–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sameshima-Saito R., Chiba K., Minamisawa K. 2006. Correlation of denitrifying capability with the existence of nap, nir, nor and nos genes in diverse strains of soybean bradyrhizobia. Microbes Environ. 21:174–184 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sameshima R., et al. 2003. Phylogeny and distribution of extra-slow-growing Bradyrhizobium japonicum harboring high copy numbers of RSa, RSb and IS1631. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 44:191–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schäfer A., et al. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simon R., Priefer U., Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology (NY) 1:784–791 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tago K., Ishii S., Nishizawa T., Otsuka S., Senoo K. 2011. Phylogenetic and functional diversity of denitrifying bacteria isolated from various rice paddy and rice-soybean rotation fields. Microbes Environ. 26:30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]