Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) infection of swine results in substantial economic losses to the swine industry worldwide. Identification of cellular factors involved in PRRSV life cycle not only will enable a better understanding of virus biology but also has the potential for the development of antiviral therapeutics. The PRRSV nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) has been shown to be involved in at least two important functions in the infected hosts: (i) mediation of viral subgenomic (sg) mRNA transcription and (ii) suppression of the host's innate immune response mechanisms. To further our understanding of the role of the viral nsp1 in these processes, using nsp1β, a proteolytically processed functional product of nsp1 as bait, we have identified the cellular poly(C)-binding proteins 1 and 2 (PCBP1 and PCBP2) as two of its interaction partners. The interactions of PCBP1 and PCBP2 with nsp1β were confirmed both by coimmunoprecipitation in infected cells and/or in plasmid-transfected cells and also by in vitro binding assays. During PRRSV infection of MARC-145 cells, the cytoplasmic PCBP1 and PCBP2 partially colocalize to the viral replication-transcription complexes. Furthermore, recombinant purified PCBP1 and PCBP2 were found to bind the viral 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR). Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated silencing of PCBP1 and PCBP2 in cells resulted in significantly reduced PRRSV genome replication and transcription without adverse effect on initial polyprotein synthesis. Overall, the results presented here point toward an important role for PCBP1 and PCBP2 in regulating PRRSV RNA synthesis.

INTRODUCTION

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is considered the most significant swine pathogen worldwide. Viral infection leads to late-term reproductive failure in pregnant sows and respiratory distress in young piglets. The most recent study (in 2011) of annual economic losses due to PRRSV infections to the U.S. swine industry alone has suggested the loss to be over $660 million (29). PRRSV is a member of the family Arteriviridae, which includes equine arteritis virus (EAV), lactate dehydrogenase elevating virus (LDV), and simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV). Together with the Coronaviridae and Roniviridae families, Arteriviridae form the order Nidovirales (4). PRRSV contains a plus-sense [(+)-sense] single-stranded RNA genome of ∼15 kb in length. The RNA genome is polyadenylated at the 3′ end and possesses a 5′ cap structure (28). The nonstructural proteins (nsp's) are encoded in the 5′-proximal two-thirds of the genomic RNA and are synthesized as polyproteins from two open reading frames (ORFs): ORF1a and ORF1b. Upon translation, the two polyproteins are cotranslationally and posttranslationally processed by four virus-encoded proteases, i.e., nsp1α, nsp1β, nsp2, and nsp4, to produce 14 different nsp's (39, 48). Some of these nsp's are assembled to form the viral replicase complex and, along with host cell components, carry out and regulate viral RNA replication, subgenomic (sg) mRNA transcription, and translation. The PRRSV structural proteins encoded by the 3′-proximal one-third of the genomic RNA are translated from a set of six nested sg mRNAs generated through a process of discontinuous RNA transcription (33, 37).

The viral genomic RNA acts as a template for protein synthesis, genome replication (synthesis of genome-length RNAs), and transcription (synthesis of sg-length RNAs) as well as for packaging into virions. These processes must be regulated by viral and host cell factors for efficient replication of the virus. Identification of such factors is challenging, as it requires uncoupling of the tightly linked processes of genome replication and transcription. Studies have identified EAV nsp1 and nsp10 as the two proteins essential for sg mRNA synthesis (45, 51). While EAV nsp1 is synthesized as a single protein due to the lack of a PCPα active-site residue, PRRSV nsp1 is autoproteolytically processed to produce nsp1α and nsp1β proteins (10). Mutations of the protease active site of PRRSV nsp1α led to a replication-competent but sg mRNA transcription-incompetent virus (22). The same study also described that mutation in the nsp1β protease active site results in a total loss of RNA replication, presumably because of the absence of cleavage of the nsp1β-nsp2 junction. More recently, it was shown that all the three subdomains of EAV nsp1 (zinc finger, PCPα, and PCPβ) are important for transcription (31). Importantly, it was shown that the PCPβ domain's involvement in sg mRNA transcription is separate from its protease function. Furthermore, nsp1 was found to regulate the relative amounts of viral mRNA by controlling the accumulation of full-length and sg-length minus (−)-strand templates (31). Besides its role in viral sg mRNA transcription, EAV nsp1 is also involved in polyprotein processing and virion biogenesis—underscoring its multifunctional role in the life cycle of the virus (45). Similar roles can also be predicted for the PRRSV orthologs, nsp1α and nsp1β. Besides their involvement in viral gene expression, both subunits of nsp1 are known inhibitors of cellular innate immune response (3, 7, 19, 34, 42).

While the number of functions attributed to arterivirus nsp1 is growing rapidly, molecular mechanisms of its involvement in various functions have not been elucidated. Identification of cellular proteins that interact with nsp1 will likely shed light on its various roles. An earlier report inferred that interaction of cellular transcriptional coactivator p100 with EAV nsp1 might be important for viral sg mRNA synthesis (46). In this study, we have identified cellular PCBP1 and PCBP2 as two interaction partners of PRRSV nsp1β. PCBPs are a group of RNA/DNA binding proteins involved in RNA metabolism (6, 24, 27). We have found that in PRRSV-infected cells, PCBP1 and PCBP2 partially localize to viral replication-transcription complexes (RTCs) and also bind to the PRRSV 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) in vitro. Depletion of PCBPs led to reduced viral genome replication and sg mRNA transcription in PRRSV-infected cells. These data collectively suggest that PCBPs facilitate viral RNA transcription and replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and plaque assay.

Human embryonic kidney 293T, MARC-145 (18), and BHK-21 cells were maintained as before (8). The infectious-clone-derived virulent North American PRRSV strain FL12 (47) and VR-2332 used in this study were propagated in MARC-145 cells. Virus titers in the culture supernatants of cells were determined by plaque assay as described before (9).

Plasmids and antibodies.

The plasmids encoding human PCBP1 (GenBank no. NM_006196) and PCBP2 (GenBank no. NM_005016) proteins with a hemagglutinin (HA) tag at their amino terminus have been described recently (11). PCBP1 and PCBP2 cDNAs were also subcloned in pET28a(+) vector (Novagen) by using NheI and EcoRI restriction enzymes to generate the plasmids pET28-PCBP1 and pET28-PCBP2, which were used for expression of the corresponding proteins in bacteria. The construction of Flag-nsp1β and Flag-nsp9 has been described previously (3, 42). For bacterial expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged nsp1β protein, nsp1β sequence was amplified from the pIHAFlag-nsp1β plasmid by using the primers (Table 1) (42) and cloned at the EcoRI and NotI sites in pET41C (+) vector (Novagen). For preparation of PRRSV 5′UTR and 3′UTR radiolabeled probes, cDNA fragments from FL12 infectious clone (GenBank accession no. AY545985) corresponding to nucleotides (nt) 1 to 191 (5′UTR) and nt 15263 to 15413 (3′UTR) were amplified by PCR using the primers (Table 1) and cloned in pCDNA3.1 (+) to obtain the plasmids pCDNA(+)-5′UTR and pCDNA(+)-3′UTR, respectively. As these cDNAs are located downstream of the T7 polymerase promoter, corresponding RNAs can be produced using the T7 RNA polymerase. The 3′UTR cDNA was also inserted in pCDNA3.1(−) to generate pCDNA(−)-3′UTR, which was used to prepare minus-sense [(−)-sense] 3′UTR for detection of (+)-sense genomic and sg RNA by Northern hybridization. The cloned cDNAs were confirmed for correct sequences and orientation by sequencing.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)a | Use |

|---|---|---|

| EcoRInsp1β for | ATATGAATTCTGGCTGACGTCTATGATATTGGTCAT | Amplification of nsp1β to clone in pET vector |

| Nsp1-R | ATATATGCGGCCGCTTTACCGTACCATTTGTGACTGC | |

| 5′UTR HindIII for | ATATAAGCTTATGACGTATAGGTGTTGGCTC | Amplification of 5′UTR |

| 5′UTR NcoI rev | ATATCCATGGTTAAAGGGTTGGAGAGA | |

| 3′UTR XbaIfor | ATATTCTAGATGGGCTGGCATTCCTTAAGC | Amplification of 3′UTR(−) |

| 3′UTR XbaIrev | ATATTCTAGAAATTTCGGCCGCATGGTTCTC | |

| T7PNforb | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGAAATAACAACGGCAAGCAGC | Amplification of 3′UTR(+) |

| 3UTR141R21rev | GCATGGTTCTCGCCAATTAAA | |

| hIFNb for | GTGTCAGAAGCTCCTGTGGC | RT-PCR for human IFN-β transcript |

| hIFNb rev | CTTCAGTTTCGGAGGTAACC |

The restriction enzyme sites are underlined.

The T7 promoter sequence is indicated in bold.

Mouse anti-β-actin (Sc-47778), normal mouse IgG1 (Sc-3877), goat anti-PCBP1 (Sc-16504), goat anti-PCBP2 (Sc-30725), mouse anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH; sc-32233), and mouse anti-green fluorescent protein (anti-GFP; Sc-9996) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotech. Mouse anti-HA (H3663) and rabbit anti-HA (H6908), anti-Flag M2 (F3165), and rabbit anti-Flag (F7425) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (goat anti-mouse [074-1807] and goat anti-rabbit [214-1516]) used for immunoblotting were purchased from Kirkegaard and Perry Ltd. (KPL). PRRSV nsp1 rabbit antibody (which detects both nsp1α and nsp1β) was prepared by immunizing rabbits with nsp1 full-length protein. The anti-nsp1β monoclonal antibody (7) was kindly provided by Ying Fang (South Dakota State University). The anti-nsp2/3 antibody was a generous gift from Eric Snijder, LUMC (22). Secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence were Alexa-Fluor 568 donkey anti-mouse, Alexa-Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit, Alexa-Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit, and Alexa-Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse.

Plasmid transfection, co-IP, and GST pulldown assay.

Cells were transfected with plasmids by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's protocol. Plasmid-transfected cells were examined at 36 to 48 h posttransfection (hpt) whereas cells infected with PRRSV were examined at 24 to 48 h postinfection (hpi). Transfected or infected cell lysates were prepared using coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) buffer as described earlier (11). Clarified cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with appropriate antibodies overnight at 4°C. IP involving anti-Flag antibody used the agarose conjugated to anti-Flag M2 antibody (Sigma). Protein A Sepharose (GE Biosciences) was used in other IP experiments as described before (11). Where indicated, the clarified lysates were treated with a mixture of RNase A (2.5 U/100 μl) and T1 (1 U/μl) for 1 h at room temperature before IP. The immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by immunoblotting (3) with appropriate antibodies. For glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assays, GST or GST-nsp1β proteins expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21 cells) were first conjugated to glutathione beads (GE Biosciences), and the conjugated beads were blocked overnight with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). These blocked beads were washed twice with TIF buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM MgCl2; 0.1% NP-40; 10% glycerol; 0.1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 1× protease inhibitor) and incubated with purified recombinant PCBP1 (rPCBP1) or PCBP2 for 2 h at room temperature. The beads were washed at least 6 times with TIF buffer followed by elution and detection of the proteins by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

siRNAs.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were purchased from Dharmacon and were used at a 20 nM final concentration, unless otherwise stated, with Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) as described previously (11).

In vitro synthesis of full-length viral transcripts, electroporation, and virus recovery.

Full-length viral in vitro transcripts were prepared as before (23, 47). The green fluorescent FL12 virus (pFLeGFP) was generated by engineering the enhanced GFP (eGFP) coding sequence between ORF1b and ORF2 coding sequence in the pFL12 infectious clone as described earlier (36). Approximately 5 μg of in vitro-transcribed RNA was electroporated in 1.25 × 106 BHK-21 cells by using Ingenio electroporation solution (Mirus Bio) in a Bio-Rad gene pulser as described before (47). Electroporated cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for indicated times before being harvested for further assays.

Bacterial protein production and purification.

Cultures of Escherichia coli (BL21) carrying pET28-PCBP1 or pET28-PCBP2 plasmids grown overnight were diluted 1:10 and then were allowed to grow to an optical density at 550 nm (OD550) of 0.55. Protein expression was induced by addition of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; 1 mM final concentration) for an additional 3.5 h. Cells were harvested by pelleting the culture, and the His-tagged PCBP1 or PCBP2 was purified from the pellets under native conditions by using the ProBond purification system (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's recommendations. Proteins were checked for purity by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining.

RNA probe preparation.

Uniformly 32P-labeled PRRSV 5′UTR and 3′UTR probes were prepared by in vitro transcription with T7 polymerase by using a T7-Riboprobe kit (Promega). pcDNA(+)-5′UTR and pcDNA(+)-3′UTR were digested with NdeI-XhoI and NdeI-ApaI enzyme pairs, respectively. The fragments containing 5′UTR or 3′UTR along with T7 promoter were purified and used in the in vitro transcription reactions. Unlabeled specific competitor RNAs were prepared by using unlabeled UTP in place of [α-32P]UTP. For nonspecific competitor RNA synthesis, a fragment of pcDNA3.1 vector DNA was used as the template. To generate the (−)-sense 3′UTR (ns3′UTR) probe, pcDNA(−)-3′UTR vector was digested with NdeI and ApaI, and the fragment containing the T7 promoter-3′UTR was used as the template in an in vitro transcription reaction as described above. For (−)-sense genomic and sg RNA detection, a longer probe encompassing nt 14896 to nt 15403 was used. PCR was performed with primers (Table 1) encompassing the above-described region of the PRRSV FL12 genome. The resulting PCR product after purification was used as the template in in vitro transcription to produce (+)-sense 3′UTR (ps3′UTR) probe. The in vitro-transcribed RNAs were purified by use of a Qiagen RNAeasy column followed by a phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The amount of radiolabel incorporation was determined by scintillation counting.

EMSA.

RNA binding reactions and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed as described previously with modifications (1). The purified probes were refolded by melting at 80°C followed by gradual cooling down to room temperature. Labeled RNA (100 nM) was incubated with the indicated amount of purified rPCBP1 or rPCBP2 in an RNA binding buffer (5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 25 mM KCl; 2 mM MgCl2; 0.1 mM EDTA; 3.8% glycerol; 2 mM DTT; 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin; 0.5 mg/ml heparin; 0.25 mg/ml Escherichia coli tRNA; 8 U of RNasin [RNase inhibitor; Promega]) for 20 min at 30°C. In the case of competition EMSAs, rPCBP1 and rPCBP2 were preincubated with specific/nonspecific competitor for 20 min at 30°C before the addition of radiolabeled probe, and the incubation was continued for another 20 min at 30°C. The resulting ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes were resolved by electrophoresis in 5% native polyacrylamide (29:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide)-5% glycerol-0.5× Tris-borate EDTA gels for 4 h. RNAs were detected by exposing the dried gel to a phosphorimager screen.

Viral RNA isolation and detection by Northern hybridization.

Total cellular RNA from PRRSV-infected MARC-145 cells was isolated at indicated times postinfection by using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Five to 10 μg of total RNA was resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis using a glyoxal-based buffer (Northernmax Gly; Ambion). Transfer of RNA to nylon membrane and hybridization with radiolabeled probe were done using the Northernmax Gly kit (Ambion) per the manufacturer's recommendations. Hybridized membranes were exposed to phosphorimager screens, and RNA bands were visualized by scanning the screens in a Bio-Rad scanner.

RT-PCR for IFN-β mRNA.

Total RNA isolated from cells as described above was reverse transcribed using oligo(dT) and Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcription (RT) kit (Invitrogen). The resulting cDNA was used in a PCR to amplify the target gene (beta interferon [IFN-β]) by using primers shown in Table 1. Cellular RPL32 (3) was also amplified to serve as the internal control.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy were performed as described previously (3).

Silver staining and mass spectrometric identification of proteins.

The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved in SDS-PAGE, and the acrylamide gels were stained with silver using a protocol described earlier (5). The stained bands were excised and subjected to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) as described before (17). Briefly, gel pieces were digested by trypsin and digested peptides were extracted in 5% formic acid-50% acetonitrile and separated using a C18 reversed-phase LC column (75 μm by 15 cm; BEH 130, 1.7 μm, Waters, Milford, MA). A quantitative time of flight (Q-TOF) Ultima tandem mass spectrometer coupled with a Nanoaquity high-performance LC (HPLC) system (Waters) with electrospray ionization was used to analyze the eluting peptides. The peak lists of MS/MS data were generated using Distiller (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) with charge state recognition and deisotoping with the other default parameters for Q-TOF data. Data base searches of the acquired MS/MS spectra were performed using Mascot (Matrix Science, v2.2.0, London, United Kingdom). The NCBI database (20100701) was used in the searches.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc). Student's unpaired t test was used to compare the viral titers. A P value of <0.05 is considered significant.

RESULTS

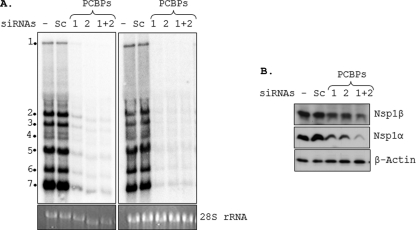

Identification of PRRSV nsp1β-interacting proteins by immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry.

In order to detect cellular proteins that potentially associate with PRRSV nsp1β inside the cell, we employed an immunoprecipitation (IP)-coupled mass spectrometry (MS) approach. A plasmid encoding Flag-tagged nsp1β or an empty vector (EV) encoding only the Flag sequences was transfected into 293T cells. Subsequently, nsp1β and its associated proteins were affinity purified using anti-Flag M2 affinity gel from the cell lysates. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. In addition to detecting several common bands in both vector and nsp1β lanes, at least four specific bands were detected in the nsp1β lane (Fig. 1, asterisk). These protein bands were subjected to MS analysis. The band migrating just above the IgG light chain (IgG-L) was identified as PRRSV nsp1β (∼27 kDa), indicating successful immunoprecipitation. Several cellular proteins were identified in the analysis of the four bands. Their identities, including the number of separate peptides detected in MS analysis and the MASCOT score, are shown in Table 2. Many of these proteins are generally involved in cellular RNA metabolism (32, 38, 55, 58). The present study is focused on two cellular proteins, PCBP1 and PCBP2, detected in band 3.

Fig. 1.

Identification of PRRSV nsp1β-interacting proteins by IP-MS. Flag-EV (Vector)- and Flag-nsp1β (nsp1β)-overexpressing 293T cells were used for immunoprecipitation using anti-Flag agarose resins. Eluted proteins were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and subjected to silver staining. The prominent bands at ∼55 kDa and ∼25 kDa are IgG heavy (IgG-H) and IgG light (IgG-L) chains, respectively. The nsp1β band is observed just above the IgG-L band in the nsp1β lane only. The four bands specific to the nsp1β lane are indicated by asterisks (*). The relative mobility of molecular mass markers (in kDa) is shown on the left.

Table 2.

List of proteins present in the four specific bands observed in nsp1β lane as identified by MS

| Band no. | Accession no. | Protein name (approx mol wt) | MASCOT scorea | Queries matchedb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | gi|4504715 | Poly(A) binding protein, cytoplasmic 4 isoform 2 (71 kDa) | 333 | 9 |

| gi|288100 | Initation factor 4B (69 kDa) | 159 | 3 | |

| gi|3122595 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX17 (72 kDa) | 132 | 3 | |

| gi|187281 | M4 protein (77 kDa) | 95 | 4 | |

| 2 | gi|14165437 | hnRNP K isoform a (51 kDa) | 404 | 14 |

| gi|5031703 | Ras-GTPase-activating protein SH3-domain-binding protein (52 kDa) | 292 | 5 | |

| gi|306890 | Chaperonin (HSP60) (60 kDa) | 167 | 6 | |

| gi|4191610 | IGF-II mRNA-binding protein 2 (65 kDa) | 118 | 3 | |

| 3 | gi|460771 | PCBP1 (38 kDa) | 340 | 9 |

| gi|14141166 | PCBP2 (38 kDa) | 325 | 9 | |

| gi|557546 | Nucleolar phosphoprotein B23 (40 kDa) | 159 | 3 | |

| gi|4504447 | hnRNP A2/B1 isoform A2 (36 kDa) | 127 | 2 | |

| 4 | gi|4506707 | Ribosomal protein S25 (14 kDa) | 136 | 3 |

| gi|5032051 | Ribosomal protein S14 (16 kDa) | 127 | 2 |

The significance threshold of proteins was set at P < 0.05.

Number of peptides sequenced found to be derived from the same proteins.

Interaction and colocalization of PCBP1 and PCBP2 with PRRSV nsp1β.

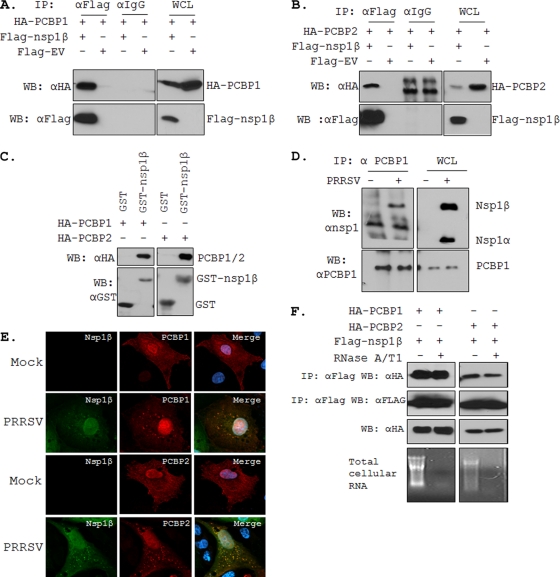

Our first objective was to confirm the PRRSV nsp1β's interaction with cellular PCBP1 and PCBP2 as observed in the MS study. Cells were transfected with Flag-nsp1β or empty vector (Flag-EV) along with plasmids encoding HA-tagged PCBP1 (HA-PCBP1) or HA-tagged PCBP2 (HA-PCBP2). IP was performed with either anti-Flag antibody or an isotype control antibody (normal mouse IgG1). The immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed for the presence of PCBP1 or PCBP2 by using anti-HA antibody. Both PCBP1 and PCBP2 could be readily detected only in the presence of Flag-nsp1β, not in the presence of Flag-EV (Fig. 2A and B). Moreover, IP with the isotype control antibody failed to pull down PCBP1 or PCBP2, suggesting that nsp1β's interaction with PCBP1 and PCBP2 is specific. Conversely, using anti-HA antibody for IP and anti-Flag antibody for immunoblotting, we could also readily detect nsp1β (data not shown), further confirming interactions between nsp1β and the two cellular PCBPs. Since the above experiments did not exclude the possibility that nsp1β-PCBP1/2 association might be mediated indirectly through other cellular protein(s), we employed GST pulldown assay using purified PCBP1 and PCBP2 (from recombinant E. coli) and glutathione beads conjugated with GST-nsp1β or GST protein. The presence of GST-nsp1β but not GST alone in the incubation mixture retained PCBP1 and PCBP2 (Fig. 2C), indicating that the interaction of cellular PCBPs with the viral nsp1β is likely due to a direct physical association.

Fig. 2.

Interaction of PCBP1 and PCBP2 with PRRSV nsp1β. Co-IP of HA-PCBP1 (A) and HA-PCBP2 (B) with Flag-nsp1β. Indicated plasmids (shown on top) were transfected into 293T cells, and at 48 hpt, whole-cell lysates (WCL) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag or anti-IgG. After SDS-PAGE separation, proteins were detected by immunoblotting with antibodies indicated on the left. A 5% aliquot of WCL was also probed similarly to confirm the expression of the proteins. The identities of various protein bands are indicated on the right. (C) GST pulldown assay. Glutathione beads conjugated to GST or GST-nsp1β fusion protein were incubated with recombinant PCBP1 (left) or PCBP2 (right). After washing, proteins were eluted from the beads and SDS-PAGE was performed. The presence of PCBP1 and PCBP2 was detected by anti-HA antibody. GST and GST-nsp1β expression was confirmed by use of anti-GST antibody. (D) Co-IP of PRRSV nsp1β with endogenous PCBP1. PRRSV-infected (+) or mock-infected (−) MARC-145 cells were used for IP with anti-PCBP1 antibody and immunoblotted with antibodies shown on the left. The identities of various bands are shown on the right. (E) Colocalization of nsp1β with HA-PCBP1 and HA-PCBP2 by confocal microscopy. MARC-145 cells were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (the VR-2332 strain was used here, since the nsp1β monoclonal antibody is against this virus) for 6 h before being transfected with the PCBP protein-expressing plasmids. Cells were fixed 18 hpt and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence to detect nsp1β (green) and HA-PCBP1 or PCBP2 (red) by using mouse anti-nsp1β and rabbit anti-HA antibodies. Position of nucleus is indicated by DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (blue) by staining in the merge image (far right). (F) Effect of RNase treatment on PCBP1/2-nsp1β interaction. Extracts of 293T cells overexpressing the different proteins were treated or untreated with RNase A and T1 for 1 h before IP and immunoblotted with antibodies shown on the left. Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels show total RNA present with or without RNase treatment. WB, Western blotting.

To examine if nsp1β interacts with these two cellular proteins in the context of PRRSV infection, we immunoprecipitated virus-infected MARC-145 cell lysates with anti-PCBP1 antibody and probed for presence of nsp1β by using an nsp1 antibody which detects both nsp1α and nsp1β. Our results showed that nsp1β but not nsp1α could be readily detected in PRRSV-infected MARC-145 cells (Fig. 2D), indicating that PCBP1 does indeed interact with endogenous nsp1β in virus-infected cells. However, we were unable to detect nsp1β-PCBP2 interaction in infected cells, most likely due to poor ability of the available PCBP2 antibody for immunoprecipitation (data not shown). We then examined the colocalization of PCBP1 and PCBP2 proteins with nsp1β by immunofluorescence microscopy in virus-infected cells. We used the HA-tagged PCBP1 and PCBP2 encoding plasmids to overexpress these proteins in MARC-145 cells which were subsequently infected with PRRSV. The confocal images of such cells immunostained with anti-HA and anti-nsp1β antibodies showed strong colocalization of both PCBP1 and PCBP2 with PRRSV nsp1β (Fig. 2E).

Since both PCBP1 and PCBP2 have strong affinity for nucleic acids and nsp1β is also known to bind nucleic acids (57), we examined whether the nsp1β-PCBP interaction might be mediated through a nonspecific RNA bridge. Results showed that RNase treatment of cell extracts before immunoprecipitation did not eliminate or reduce the nsp1β-PCBP interactions, indicating that these interactions are not due to nonspecific RNA-mediated binding (Fig. 2F).

PCBP1 and PCBP2 colocalize to viral RTC.

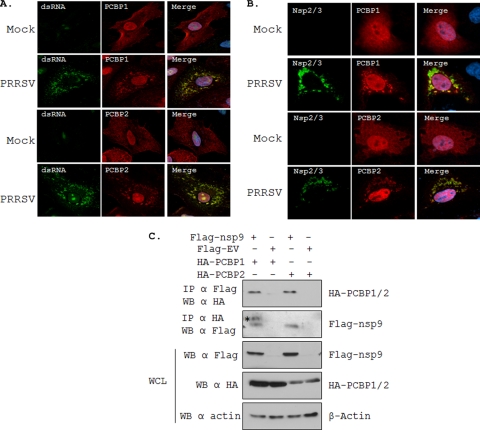

Since PCBPs are known to influence viral replication (11, 27), we investigated whether they play any role in PRRSV replication. First we examined if PCBPs associate with the intracellular structures that contain viral replication and transcription complex (RTC), where viral replication and transcription occurs (12). The RTCs contain viral proteins that are involved in genome replication and transcription as well as double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), an RNA intermediate in replication for several positive-strand RNA viruses including EAV (20). Such RTCs have been identified in virus-infected cells by using antibodies against dsRNA (20, 43, 53, 54). By using antibodies against dsRNA and PCBPs, we observed strong colocalization of cytoplasmic PCBPs with dsRNA-containing structures in PRRSV-infected cells but not in mock-infected cells (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, using an antibody that recognizes both nsp2 and nsp3 proteins, the two viral proteins which are required for PRRSV replication and transcription and are involved in the formation of the viral RTC in arteriviruses (35, 40), results showed colocalization of nsp2 and nsp3 proteins with the PCBPs (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the PCBPs are present in the viral RTCs. Interestingly, the PCBPs appear to be uniformly distributed both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus in mock-infected MARC-145 cells (Fig. 3A and B), but upon PRRSV infection, the cytoplasmic fraction of PCBPs appears to localize to punctate structures, the majority of which are located in close proximity to the viral RTC, as judged by PRRSV nsp2/3 and dsRNA staining. It is known that the binding of nucleic acids to PCBPs results in punctate staining pattern of these proteins (2). The localization of PCBP1 and PCBP2 in PRRSV-infected cells to viral RTCs may thus be suggestive of their role in viral replication and transcription.

Fig. 3.

Colocalization of PCBP1 and PCBP2 with dsRNA and nsp's in PRRSV-infected cells. (A) MARC-145 cells were mock infected or infected with PRRSV (strain VR-2332) for 6 h before being transfected with the PCBP protein-expressing plasmids. Cells were fixed 18 hpt and were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence to detect dsRNA (green) and HA-PCBP1 and HA-PCBP2 (red) by using mouse anti-dsRNA (J2) and rabbit anti-HA antibodies, respectively. (B) MARC-145 cells were treated as described above, and indirect immunofluorescence was performed to detect PCBP1 or PCBP2 (red) and PRRSV nsp2/3 (green) by using mouse anti-HA antibody and rabbit anti-nsp2/3 antibody, respectively. Nuclei are shown by DAPI (blue) staining in the merge image (far right). (C) Interaction of HA-PCBP1 and HA-PCBP2 with Flag-nsp9. Indicated plasmids (shown on top) were transfected into 293T cells, and at 48 hpt, whole-cell extracts were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with antibodies indicated on the left. A 5% whole-cell lysate (WCL) sample was also probed similarly to show the expression of the proteins. The identities of various protein bands are indicated on the right. Asterisk, nonspecific band.

An integral component of the viral RTC is the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, the nsp9 of PRRSV. The unavailability of a PRRSV nsp9-specific antibody prevented us from exploring the interaction of nsp9 with PCBPs in virus-infected cells. However, in cells expressing Flag-tagged nsp9 and HA-tagged PCBP1 or PCBP2, we could readily demonstrate the interactions between nsp9 and the PCBPs (Fig. 3C). These results show that nsp9 interacts with both of these cellular proteins in transfected cells. Overall, our results suggest that PCBPs are likely localized to the viral RTC and may be important for viral replication.

PCBP1 and PCBP2 bind to the PRRSV 5′ UTR.

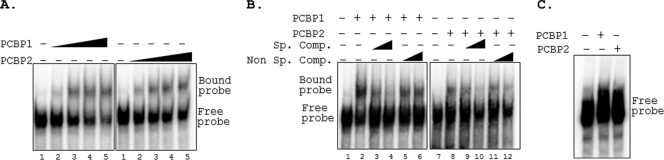

PCBPs have been reported to interact with 5′UTR and/or 3′UTR of viral as well as cellular RNAs and affect the transcription, stability, and translation of RNA (27). To examine the possible interactions of PCBPs with PRRSV genomic termini, radiolabeled 5′UTR or 3′UTR of the PRRSV genome was incubated with increasing concentrations of purified PCBP1 or PCBP2 protein, and the formation of slow-migrating ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes was examined by EMSA. The results (Fig. 4A) revealed that the 5′UTR formed complexes with both PCBP1 and PCBP2. This RNP complex formation was specific to the PRRSV 5′UTR, as the addition of an increasing concentration of a specific competitor RNA (unlabeled 5′UTR) resulted in a significant reduction in complex formation in a dose-dependent manner, whereas a nonspecific unlabeled competitor RNA was unable to significantly reduce the complex formation (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, the PCBPs did not form complexes with 3′UTR RNA (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results indicate that the cellular PCBPs specifically bind to the PRRSV 5′UTR.

Fig. 4.

PCBP1 and PCBP2 form complexes with PRRSV 5′UTR. (A) EMSA of 32P-labeled PRRSV (+) 5′UTR probe in the presence of increasing concentrations (0, 0.5, 0.75, 1, and 1.25 μg in lanes 1 to 5) of recombinant purified PCBP1 or PCBP2 in an RNA binding reaction. RNP complexes were resolved by 5% nondenaturing PAGE and visualized by exposing the dried gel to phosphorimager screens. The positions of the free and bound probes are indicated on the right. (B) Competition gel mobility shift assay. Radiolabeled PRRSV (+) 5′UTR probes were incubated with 0.75 μg of PCBP1 or PCBP2 in presence (+) or absence (−) of unlabeled 5′UTR probe (Sp. comp.) or an irrelevant probe (Non Sp. comp.). Lanes: 1 and 7, free probe; 2 and 8, no competitor; 3, 4, 9, and 10, increasing concentration of specific competitor (10-fold and 50-fold molar excess); 5, 6, 11, and 12, increasing concentration of nonspecific competitor (10-fold and 50-fold molar excess). (C) Gel mobility shift assay with 3′UTR. Radiolabeled PRRSV (+) 3′UTR probe was incubated without (−) or with (+) 1 μg of PCBP1 or PCBP2, and EMSA was performed as described above.

Depletion of PCBP1 and/or PCBP2 from cells results in PRRSV growth inhibition.

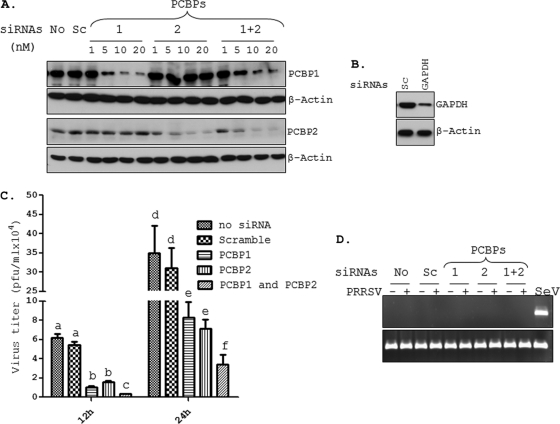

The observations that PCBPs interact with the viral nsp1β, RdRp, as well as with the viral 5′UTR led us to hypothesize that these factors play important roles in the viral life cycle. The biological consequences of these interactions were first examined by determining the extent of growth of PRRSV in cells depleted of these cellular proteins by using siRNA-mediated silencing of PCBP1 or PCBP2 gene expression. Since PCBP1 and PCBP2 have been known to play overlapping roles (52), we also examined virus growth in cells depleted of both proteins simultaneously. Figure 5A shows the dose-dependent reduction in PCBP1 and PCBP2 protein levels at 72 h post-siRNA treatment in MARC-145 cells. The silencing efficiency of our siRNA transfection protocol was determined by siRNA against the highly abundant GAPDH gene (Fig. 5B). Similarly, the siRNA delivery efficiency was determined to be approximately 80% (data not shown) by using siRNA against the cellular polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), silencing of which leads to apoptosis of cells (26). When the PCBP1- or PCBP2-silenced MARC-145 cells were infected with the genotype II PRRSV strain FL12, virus yield in the culture supernatants was substantially downregulated at 12 h and 24 h postinfection. The depletion of PCBP1 or PCBP2 in these cells led to an average 4- to 6-fold decrease in virus titers compared to what was seen for cells with no siRNA treatment or scrambled siRNA treatment (Fig. 5C). This inhibitory effect on virus yield was also observed at a higher multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 and a later time postinfection (48 h) (data not shown). Furthermore, the depletion of both proteins simultaneously resulted in a greater reduction (more than 10-fold) of virus yield (Fig. 5C). Depletion of PCBP1 and/or PCBP2 also led to a similar inhibition of growth of Lelystad virus, a genotype I PRRSV strain (data not shown), suggesting that the role of PCBPs in PRRSV growth is conserved across genotypes.

Fig. 5.

Silencing of PCBP1 and PCBP2 results in reduced PRRSV growth. (A) Reduction in PCBP1 and PCBP2 protein levels after siRNA treatment. MARC-145 cells transfected with no siRNA (No), scramble siRNA (Sc), or different concentrations (nM) of siRNAs for PCBP1 and/or PCBP2 (as shown on top of the lanes) were harvested 72 hpt. Endogenous PCBP1 and PCBP2 were detected by immunoblotting using antibodies directed against these proteins. The blots were also probed for β-actin to confirm equal protein loading. (B) MARC-145 cells were treated with scramble (Sc) or GAPDH-specific siRNAs for 72 h, and GAPDH protein was detected by immunoblotting. (C) MARC-145 cells treated for 72 h with various siRNAs were infected with FL12 virus at an MOI of 0.1. Culture supernatants were harvested at 12 h and 24 hpi, and viral titers were determined by plaque assay. Error bars represent standard error of mean from 3 different experiments. Mean titers which are significantly different are labeled with different letters on top of the bar. (D) The IFN-β mRNA and RPL32 mRNA (internal control) were measured by RT-PCR from MARC-145 cells treated with indicated siRNAs (on top) and either mock infected or infected with FL12 virus for 18 h. Sendai virus (SeV)-infected MARC-145 cells were used as a positive control for IFN induction.

Since PCBP2 is a negative modulator of IFN production (59), it is possible that the reduction in PRRSV growth upon PCBP2 knockdown might be caused by increased IFN production. Therefore, we examined the levels of IFN-β transcripts in MARC-145 cells treated with PCBP2 siRNA and infected with PRRSV. Sendai virus (SeV)-stimulated MARC-145 cells were used as a positive control for IFN induction. Results show that IFN-β induction was not observed in these cells (Fig. 5D), indicating that reduced PRRSV growth in PCBP1- or PCBP2-deficient cells is not a result of increased IFN production.

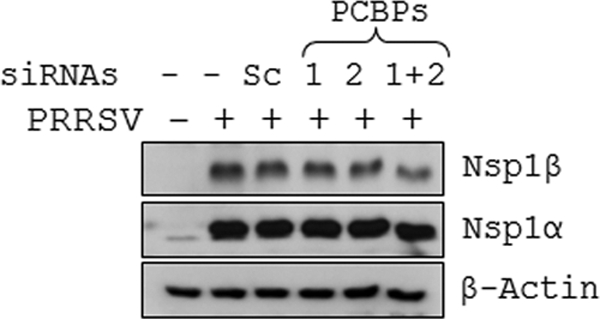

PCBP1 and PCBP2 do not affect the translation from viral genomic RNA.

Following viral entry and uncoating, the released viral genome serves as the template for translation of the nsp's from ORF1a and ORF1b, which are required for the assembly of replication complex and subsequent viral genome replication. Using a polymerase-defective PRRSV (FL12Pol−) genome, we investigated whether PCBPs are required for this initial translation event. Due to mutations in the polymerase active site, FL12Pol− virus genome cannot undergo replication (47) but the initial translation from the input viral RNA remains unaffected. Electroporation of FL12Pol− in vitro transcripts yielded similar levels of nsp1α and nsp1β proteins in both PCBP1- and PCBP2-specific siRNA-treated cells as well as scramble siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 6), implying that PCBPs are not involved in translation of the input viral genome. Thus, the above-described experiments indicate that PCBPs are required at a step beyond the initial genomic RNA translation.

Fig. 6.

PCBP1 and PCBP2 are not required for the translation of genomic RNA. BHK-21 cells treated with siRNAs (20 nM) shown on top of each lane for 72 h before being electroporated with pFL12Pol− full-length RNA. At 24 h postelectroporation, cells were harvested and PRRSV nsp1α and nsp1β proteins were detected by immunoblotting. The level of β-actin was measured to ensure equal protein loading. The left lane shows protein from BHK-21 cells that were neither siRNA treated nor electroporated with pFL12Pol− RNA.

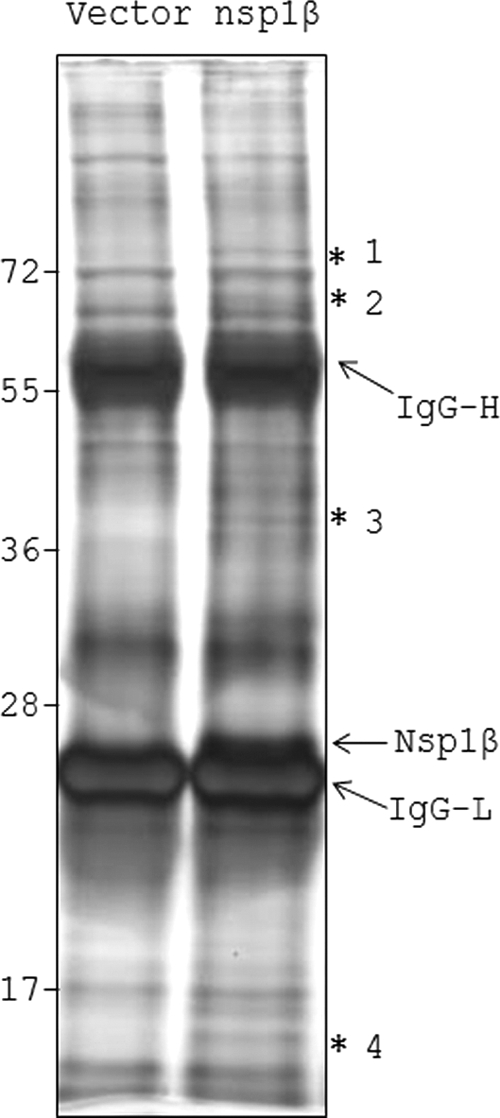

PCBP1 and PCBP2 affect viral genome replication.

To examine whether PCBPs play any role in viral RNA synthesis, MARC-145 cells, which are depleted of PCBP1 and/or PCBP2 by siRNA treatment, were infected with PRRSV. Examination of PRRSV genomic RNA and sg mRNA levels in cells depleted of these proteins revealed that the synthesis of the viral RNAs was significantly reduced from that in cells not depleted of the proteins (Fig. 7A, left). The synthesis of antigenomic RNA and antisubgenomic mRNAs was also similarly affected (Fig. 7A, right). In PCBP1- and PCBP2-deficient cells, reduced levels of nsp1α and nsp1β protein accumulation were also observed compared to cells treated with scramble siRNA or cells not treated with siRNA (Fig. 7B). Reduced levels of other nsp's (nsp2 and nsp3) as well as structural proteins (GP5, M, and N) were also observed (data not shown), suggesting that the involvement of PCBP1 and PCBP2 is not specific to a particular viral gene. Taken together, these results suggest that silencing of PCBP1 and PCBP2 has a significant inhibitory effect on the accumulation of genomic and subgenomic RNAs.

Fig. 7.

Cellular PCBP1 and PCBP2 are required for efficient PRRSV genome replication and transcription. (A) After 72 h of siRNA transfection, MARC-145 cells were infected with FL12 at an MOI of 1 for 12 h, after which the cells were collected and total RNA was isolated. Five micrograms of total RNA from each treatment was used for Northern hybridization with a radiolabeled (−) 3′UTR probe to detect viral genomic and subgenomic mRNAs (top left). Similarly, antisubgenomic and antigenomic RNAs were detected from 10 μg of total RNA by using a radiolabeled (+) 3′UTR probe (top right). The 28S rRNA levels in the samples are shown at the bottom. The genomic and antigenomic RNA and the subgenomic and antisubgenomic RNAs are identified by number 1 and numbers 2 to 7, respectively. (B) MARC-145 cells treated with siRNAs as shown on top of each lane were infected with FL12 virus at an MOI of 0.1. Cells were harvested 18 hpi and viral nonstructural proteins (nsp1α and nsp1β) levels were detected by immunoblotting. Actin served as the loading control.

DISCUSSION

Because of their limited genome coding capacity, viruses depend on host factors to carry out important functions. During the course of evolution, each virus has acquired a unique array of multifunctional proteins. The arterivirus nsp1 turns out to be one such protein. Previous studies on nsp1 of EAV and PRRSV have suggested that this protein is a major regulator of virus replication as well as a potent suppressor of host innate immune response (3, 7, 19, 34, 45). In this article, by using PRRSV nsp1β as bait, we identified several cellular proteins that interact with this viral protein, and these cellular proteins may play an important role(s) in the viral life cycle. Although the studies reported here focus on PCBPs, our IP-MS results have identified several other proteins of interest (Table 2). Specifically, several hnRNP proteins, e.g., hnRNP K and hnRNP A2/B1, were identified, which have been shown to be important for replication of other viruses such as coronaviruses (25, 38, 55). Another protein of interest is the cellular poly(A) binding protein cytoplasmic 4 (PABP4), which is known to be expressed upon T-cell activation and is involved in RNA stabilization and translation (32, 58). A common property among these putative nsp1β-interacting proteins is their inherent RNA binding ability. It will be interesting to explore the possible involvement of these cellular proteins in PRRSV life cycle, particularly in viral genome replication and transcription. As nsp1β has also been predicted to interact with RNA, these proteins together with nsp1β might form RNP complexes and play important regulatory roles in virus life cycle (30, 57).

The nsp1β-PCBP interaction was confirmed both under ectopic expression conditions and in PRRSV-infected cells. Although RNase treatment did not alter nsp1β-PCBP1/2 interaction, it is possible that these interacting partners might interact through a specific RNA moiety that is protected from RNases. The observation of partial colocalization of PCBP1/2 to viral RTC upon PRRSV infection of cells is consistent with a recent report, which suggests that only 25% of total EAV nsp1 in infected cells is present in the cytoplasmic RTC-containing cellular fraction (50). Together with nsp1β's presumed role in sg mRNA synthesis, these results indicate possible recruitment of PCBPs to the viral RTCs through interactions with PRRSV nsp1β for viral RNA synthesis. Additionally, nsp1β and PCBP1/2 were also found to colocalize in the nucleus (Fig. 2E). Both nsp1α and nsp1β of PRRSV are known to translocate to the nucleus during late times of infection (7). The functional significance of the interaction of these proteins in the nucleus is unclear, but it is possible that these complexes might regulate cellular RNA metabolism in the nucleus.

Two arteriviral proteins, nsp2 and nsp3, are implicated in modifying the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane to form double membrane vesicles (DMVs), which are the sites for viral genome amplification (40). Since PRRSV nsp2/3 and the cytoplasmic fraction of PCBP1/2 localize together in virus-infected cells (Fig. 4), we attempted to verify this interaction by co-IP experiments. Such experiments did not yield unequivocal results, indicating that the association might be a indirect, weak, or transient one that is not readily detectable by routine co-IP procedures. On the other hand, the interaction of the PRRSV nsp9 (the viral RdRp) with PCBP1/2 could be readily demonstrated when these proteins were expressed ectopically. Demonstration of a similar interaction in virus-infected cells will be important for understanding the functional consequences of this interaction in viral genome replication.

Arteriviral 5′UTR contains cis-acting sequences required for genome replication and sg mRNA production (49). The PCBPs have been reported to bind both 5′UTR and 3′UTR of cellular as well as viral genes and affect RNA metabolism. Binding of PCBP1 and PCBP2 to the promoter of mouse mu opioid receptor and BRCA1 enhances their transcription (21, 44). PCBP2 has been shown to bind the 3′UTR of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA and increase mRNA stabilization and translation (56). A previous study had identified four MA104 cell proteins, with approximate molecular masses of 103, 86, 55, and 36 kDa, of unknown identity interacting with SHFV 3′UTR of (−)-sense genome (which is antisense to viral 5′UTR) (16). Using gel mobility shift assays, we have also demonstrated that PCBP1 and PCBP2 bind to PRRSV (+) 5′UTR. As the molecular masses of PCBPs are ∼40 kDa, it is possible that one of those proteins bound to SHFV (−) 3′UTR might be PCBP. The 191-nt 5′UTR of type II PRRSV contains several pyrimidine-rich stretches, which are considered possible sites for PCBP binding. Especially, the 3′ terminal 15 nt (from nt 177 to nt 191) of the 5′UTR, which are highly conserved across arteriviruses (49), have strong homology (only 2 nt difference) with the consensus PCBP binding site on cellular mRNAs (15). It is possible that PCBPs may bind specifically to these conserved sequences to modulate viral genome transcription. It would be interesting to investigate if the PCBP-nsp1β interaction is required for PCBP's binding to PRRSV 5′UTR or if these are two mutually exclusive events.

Using an siRNA-mediated silencing approach, we have established the importance of PCBPs for PRRSV genome replication/transcription. Both PCBP1 and PCBP2 are closely related (∼90% amino acid identity). Although these two proteins are known to have overlapping functions (52), our results presented here indicate that they might be involved in yet-unknown nonoverlapping activities in PRRSV replication, as the simultaneous depletion of both proteins led to an additive reduction in viral growth compared to individual depletion (Fig. 5C). PCBP1 and PCBP2 do not appear to be involved in translation from genomic RNA. However, genomic and antigenomic RNA synthesis was reduced in the PCBP1/2-deficient cells (Fig. 7A). The observation that PCBPs bind specifically to the 5′UTR of PRRSV prompts a critical question related to viral RNA synthesis: how does this binding influence genome replication, which initiates from the 3′UTR? Studies from poliovirus replicative cycle may offer an interesting explanation in this regard. Binding of PCBP1 and PCBP2 to the 5′ cloverleaf (5′CL) structure of poliovirus stimulates the association of viral polymerase precursor (3CDpro) with the 5′CL (13). Binding of poly(A) binding protein (PABP) to the 3′UTR poly(A) tail and its interaction with the PCBP2 and 3CDpro then lead to genome circularization and replication initiation (14). Such genome circularization has been suggested as a universal mechanism for (+)-strand RNA virus replication, including that of coronaviruses (41). It is possible that the PCBPs might be an integral part of such an RNP complex that is required for the initiation of negative-strand RNA synthesis in PRRSV.

The inhibitory effect on sg RNA synthesis upon PCBP1/2 depletion could be the result of reduced levels of full-length genome and antigenome synthesis or could be due to a loss of direct interaction of PCBP1/2 with transcription-controlling cis-acting elements within the viral genome. Nidoviral sg RNAs are produced through the process of discontinuous transcription, which has been proposed to involve physical interaction between the leader transcription-regulating sequence (TRS-L) and the body TRSs (TRS-B), which are present upstream of each ORF within the viral genome. It is possible that PCBPs might interact with TRS-L and TRS-B and might help to bring together these distant RNA moieties. Further studies will be required to address the interactions of PCBP1/2 with the TRSs and how these interactions might regulate sg RNA synthesis in PRRSV-infected cells.

Overall, our studies reveal two cellular factors, PCBP1 and PCBP2, as being important regulators of PRRSV replication. They both have affinity for viral 5′UTR and interact with two viral replicase proteins. Whether PRRSV's dependence on PCBPs is also true for other arteriviruses needs further investigation. Considering the similarity in their replication strategies, these cellular proteins might also be important for other members of the Nidovirales order.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from USDA NRICGP (project no. 2008-00903 to F.A.O. and project no. 2009-01654 to A.K.P.).

We thank Terry Fangman (UNL Microscopy Core) for invaluable help in confocal microscopy. The assistance of Ron Cerny (UNL Proteomics Core Facility) in performing and analyzing the mass spectrometry experiments is greatly appreciated. We also thank Sakthivel Subramaniam, Byungjoon Kwon, and Hiep Vu for scientific input and technical assistance. We are also grateful to other members of the Osorio and Pattnaik laboratories for helpful discussions. PRRSV nsp1β and nsp2/3 antibodies were kind gifts from Ying Fang, SDSU, and Eric Snijder, LUMC, respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andino R., Rieckhof G. E., Baltimore D. 1990. A functional ribonucleoprotein complex forms around the 5′ end of poliovirus RNA. Cell 63:369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berry A. M., Flock K. E., Loh H. H., Ko J. L. 2006. Molecular basis of cellular localization of poly C binding protein 1 in neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 349:1378–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beura L. K., et al. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 1beta modulates host innate immune response by antagonizing IRF3 activation. J. Virol. 84:1574–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cavanagh D. 1997. Nidovirales: a new order comprising Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae. Arch. Virol. 142:629–633 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Celis J. E., et al. (ed.) 2006. Protein detection in gels by silver staining: a procedure compatible with mass-spectrometry, 3rd ed., vol. 4 Elsevier, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaudhury A., Chander P., Howe P. H. 2010. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) in cellular processes: focus on hnRNP E1's multifunctional regulatory roles. RNA 16:1449–1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Z., et al. 2010. Identification of two auto-cleavage products of nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infected cells: nsp1 function as interferon antagonist. Virology 398:87–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Das P. B., et al. 2010. The minor envelope glycoproteins GP2a and GP4 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus interact with the receptor CD163. J. Virol. 84:1731–1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Das P. B., et al. 2011. Glycosylation of minor envelope glycoproteins of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in infectious virus recovery, receptor interaction, and immune response. Virology 410:385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. den Boon J. A., et al. 1995. Processing and evolution of the N-terminal region of the arterivirus replicase ORF1a protein: identification of two papainlike cysteine proteases. J. Virol. 69:4500–4505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dinh P. X., Beura L. K., Panda D., Das A., Pattnaik A. K. 2011. Antagonistic effects of cellular poly(C) binding proteins on vesicular stomatitis virus gene expression. J. Virol. 85:9459–9471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fang Y., Snijder E. J. 2010. The PRRSV replicase: exploring the multifunctionality of an intriguing set of nonstructural proteins. Virus Res. 154:61–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gamarnik A. V., Andino R. 2000. Interactions of viral protein 3CD and poly(rC) binding protein with the 5′ untranslated region of the poliovirus genome. J. Virol. 74:2219–2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herold J., Andino R. 2001. Poliovirus RNA replication requires genome circularization through a protein-protein bridge. Mol. Cell 7:581–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holcik M., Liebhaber S. A. 1997. Four highly stable eukaryotic mRNAs assemble 3′ untranslated region RNA-protein complexes sharing cis and trans components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:2410–2414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hwang Y. K., Brinton M. A. 1998. A 68-nucleotide sequence within the 3′ noncoding region of simian hemorrhagic fever virus negative-strand RNA binds to four MA104 cell proteins. J. Virol. 72:4341–4351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kayser J. P., Vallet J. L., Cerny R. L. 2004. Defining parameters for homology-tolerant database searching. J. Biomol. Tech. 15:285–295 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim H. S., Kwang J., Yoon I. J., Joo H. S., Frey M. L. 1993. Enhanced replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus in a homogeneous subpopulation of MA-104 cell line. Arch. Virol. 133:477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim O., Sun Y., Lai F. W., Song C., Yoo D. 2010. Modulation of type I interferon induction by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and degradation of CREB-binding protein by non-structural protein 1 in MARC-145 and HeLa cells. Virology 402:315–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knoops K. 2011. Nidovirus replication structures. PhD thesis. Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ko J. L., Loh H. H. 2005. Poly C binding protein, a single-stranded DNA binding protein, regulates mouse mu-opioid receptor gene expression. J. Neurochem. 93:749–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kroese M. V., et al. 2008. The nsp1alpha and nsp1 papain-like autoproteinases are essential for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus RNA synthesis. J. Gen. Virol. 89:494–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kwon B., Ansari I. H., Pattnaik A. K., Osorio F. A. 2008. Identification of virulence determinants of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus through construction of chimeric clones. Virology 380:371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leffers H., Dejgaard K., Celis J. E. 1995. Characterisation of two major cellular poly(rC)-binding human proteins, each containing three K-homologous (KH) domains. Eur. J. Biochem. 230:447–453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu P. (ed.). 2010. RNA higher-order structures within the coronavirus 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions and their roles in viral replication. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu X., Erikson R. L. 2003. Polo-like kinase (Plk)1 depletion induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:5789–5794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Makeyev A. V., Liebhaber S. A. 2002. The poly(C)-binding proteins: a multiplicity of functions and a search for mechanisms. RNA 8:265–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meulenberg J. J. 2000. PRRSV, the virus. Vet. Res. 31:11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miller M. 2011. PRRS price tag, $664 million. In Miller M. (ed.), Porknetwork. http://www.porknetwork.com/pork-news/PRRS-price-tag-641-million-127963843.html [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nedialkova D. 2010. Exploring regulatory functions and enzymatic activities in the nidovirus replicase. PhD thesis. Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nedialkova D. D., Gorbalenya A. E., Snijder E. J. 2010. Arterivirus Nsp1 modulates the accumulation of minus-strand templates to control the relative abundance of viral mRNAs. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Okochi K., Suzuki T., Inoue J., Matsuda S., Yamamoto T. 2005. Interaction of anti-proliferative protein Tob with poly(A)-binding protein and inducible poly(A)-binding protein: implication of Tob in translational control. Genes Cells 10:151–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pasternak A. O., Spaan W. J., Snijder E. J. 2006. Nidovirus transcription: how to make sense? J. Gen. Virol. 87:1403–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Patel D., et al. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus inhibits type I interferon signaling by blocking STAT1/STAT2 nuclear translocation. J. Virol. 84:11045–11055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pedersen K. W., van der Meer Y., Roos N., Snijder E. J. 1999. Open reading frame 1a-encoded subunits of the arterivirus replicase induce endoplasmic reticulum-derived double-membrane vesicles which carry the viral replication complex. J. Virol. 73:2016–2026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pei Y., et al. 2009. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus as a vector: immunogenicity of green fluorescent protein and porcine circovirus type 2 capsid expressed from dedicated subgenomic RNAs. Virology 389:91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sawicki S. G., Sawicki D. L., Siddell S. G. 2007. A contemporary view of coronavirus transcription. J. Virol. 81:20–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shi S. T., Yu G. Y., Lai M. M. 2003. Multiple type A/B heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) can replace hnRNP A1 in mouse hepatitis virus RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 77:10584–10593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Snijder E. J., Meulenberg J. J. 1998. The molecular biology of arteriviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 79:961–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Snijder E. J., van Tol H., Roos N., Pedersen K. W. 2001. Non-structural proteins 2 and 3 interact to modify host cell membranes during the formation of the arterivirus replication complex. J. Gen. Virol. 82:985–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sola I., Mateos-Gomez P. A., Almazan F., Zuniga S., Enjuanes L. 2011. RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions in coronavirus replication and transcription. RNA Biol. 8:237–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Subramaniam S., et al. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus non-structural protein 1 suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter activation by inhibiting NF-kappaB and Sp1. Virology 406:270–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Targett-Adams P., Boulant S., McLauchlan J. 2008. Visualization of double-stranded RNA in cells supporting hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 82:2182–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thakur S., et al. 2003. Regulation of BRCA1 transcription by specific single-stranded DNA binding factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:3774–3787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tijms M. A., Nedialkova D. D., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J. C., Gorbalenya A. E., Snijder E. J. 2007. Arterivirus subgenomic mRNA synthesis and virion biogenesis depend on the multifunctional nsp1 autoprotease. J. Virol. 81:10496–10505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tijms M. A., Snijder E. J. 2003. Equine arteritis virus non-structural protein 1, an essential factor for viral subgenomic mRNA synthesis, interacts with the cellular transcription co-factor p100. J. Gen. Virol. 84:2317–2322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Truong H. M., et al. 2004. A highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus generated from an infectious cDNA clone retains the in vivo virulence and transmissibility properties of the parental virus. Virology 325:308–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Aken D., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J., Gorbalenya A. E., Snijder E. J. 2006. Proteolytic maturation of replicase polyprotein pp1a by the nsp4 main proteinase is essential for equine arteritis virus replication and includes internal cleavage of nsp7. J. Gen. Virol. 87:3473–3482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Van Den Born E., Gultyaev A. P., Snijder E. J. 2004. Secondary structure and function of the 5′-proximal region of the equine arteritis virus RNA genome. RNA 10:424–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van Hemert M. J., de Wilde A. H., Gorbalenya A. E., Snijder E. J. 2008. The in vitro RNA synthesizing activity of the isolated arterivirus replication/transcription complex is dependent on a host factor. J. Biol. Chem. 283:16525–16536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. van Marle G., van Dinten L. C., Spaan W. J., Luytjes W., Snijder E. J. 1999. Characterization of an equine arteritis virus replicase mutant defective in subgenomic mRNA synthesis. J. Virol. 73:5274–5281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Waggoner S. A., Johannes G. J., Liebhaber S. A. 2009. Depletion of the poly(C)-binding proteins alphaCP1 and alphaCP2 from K562 cells leads to p53-independent induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKN1A) and G1 arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 284:9039–9049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weber F., Wagner V., Rasmussen S. B., Hartmann R., Paludan S. R. 2006. Double-stranded RNA is produced by positive-strand RNA viruses and DNA viruses but not in detectable amounts by negative-strand RNA viruses. J. Virol. 80:5059–5064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Westaway E. G., Mackenzie J. M., Kenney M. T., Jones M. K., Khromykh A. A. 1997. Ultrastructure of Kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J. Virol. 71:6650–6661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wolf D., et al. 2008. HIV Nef enhances Tat-mediated viral transcription through a hnRNP-K-nucleated signaling complex. Cell Host Microbe 4:398–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xu L., Sterling C. R., Tank A. W. 2009. cAMP-mediated stimulation of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA translation is mediated by polypyrimidine-rich sequences within its 3′-untranslated region and poly(C)-binding protein 2. Mol. Pharmacol. 76:872–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xue F., et al. 2010. The crystal structure of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein Nsp1beta reveals a novel metal-dependent nuclease. J. Virol. 84:6461–6471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang H., Duckett C. S., Lindsten T. 1995. iPABP, an inducible poly(A)-binding protein detected in activated human T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6770–6776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. You F., et al. 2009. PCBP2 mediates degradation of the adaptor MAVS via the HECT ubiquitin ligase AIP4. Nat. Immunol. 10:1300–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]