Abstract

Human species A adenoviruses (HAdVs) comprise three serotypes: HAdV-12, -18, and -31. These viruses are common pathogens and cause systemic infections that usually involve the airways and/or intestine. In immunocompromised individuals, species A adenoviruses in general, and HAdV-31 in particular, cause life-threatening infections. By combining binding and infection experiments, we demonstrate that coagulation factor IX (FIX) efficiently enhances binding and infection by HAdV-18 and HAdV-31, but not by HAdV-12, in epithelial cells originating from the airways or intestine. This is markedly different from the mechanism for HAdV-5 and other human adenoviruses, which utilize coagulation factor X (FX) for infection of host cells. Surface plasmon resonance experiments revealed that the affinity of the HAdV-31 hexon-FIX interaction is higher than that of the HAdV-5 hexon-FX interaction and that the half-lives of these interactions are profoundly different. Moreover, both HAdV-31–FIX and HAdV-5–FX complexes bind to heparan sulfate-containing glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) on target cells, but binding studies utilizing cells expressing specific GAGs and GAG-cleaving enzymes revealed differences in GAG dependence and specificity between these two complexes. These findings add to our understanding of the intricate infection pathways used by human adenoviruses, and they may contribute to better design of HAdV-based vectors for gene and cancer therapy. Furthermore, the interaction between the HAdV-31 hexon and FIX may also serve as a target for antiviral treatment.

INTRODUCTION

In immunocompetent individuals, human adenoviruses (HAdVs) cause self-limiting diseases that affect the intestine, airways, urinary tract, tonsils, and/or eyes (74). Species A HAdVs (HAdV-12, -18, and -31) are common pathogens in humans (64) and are associated with cryptic, disseminated gastrointestinal and/or respiratory infections, usually in children under the age of 4 years (2, 14, 48, 60). In immunocompromised individuals (AIDS patients, organ transplant patients, or patients with congenital immune deficiencies), species A HAdVs in general, and HAdV-31 in particular, cause severe and sometimes lethal infections (18, 25, 29, 35, 37–38). In this group of patients, the symptoms are similar to those in immunocompetent patients but more severe, and they also include hepatitis.

The icosahedral adenovirus particle is composed of three major capsomers: the fiber, the penton base, and the hexon protein. The trimeric fiber proteins contain the terminal knob domain, which directly binds virions to cellular receptors, such as the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) (11, 58, 63), desmoglein 2 (68), CD46 (22, 42, 61), or sialic-acid-containing glycans (7–8, 47), in a species- and/or serotype-specific manner. The pentameric penton base proteins contain conserved RGD motifs (except in HAdV-40 and HAdV-41) (5) that interact with cellular integrins (44) in vitro, resulting in endocytosis (10, 72) and endosomal release (69, 71). The trimeric hexon protein is the major building block of the capsid and encapsidates the viral DNA. Recent findings also demonstrate that the HAdV-5 hexon binds with high affinity to coagulation factor X (FX), which, in turn, binds to hepatocyte surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), resulting in entry and infection both in vitro and in vivo (3, 32, 65). HAdV-FX entry and trafficking pathways, however, also depend on the fiber protein (15). The role of FX was identified in an attempt to explain the pronounced hepatic tropism of HAdV-5-based gene therapy vectors administered to the blood. However, the evolution of such high-affinity interactions suggests important functions during the natural course of wild-type (wt) HAdV infections as well. We reported recently that HAdV-31 uses FIX but not FX for efficient binding to and infection of cells that correspond to the HAdV-31 tropism in immunocompetent individuals (31). In this case, the role of cell surface heparan sulfate was unclear. In this study, we set out to (i) investigate whether the usage of coagulation factors is a mechanism common to all species A HAdVs, (ii) characterize the HAdV-31–FIX interaction in detail, and (iii) identify the cellular receptor for the HAdV-31–FIX complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and antibodies.

Human epithelial FHs74Int cells (derived from small intestine) were purchased from LGC Promochem (Teddington, United Kingdom) and were grown according to the supplier's instructions. A549 cells (a gift from Alistair Kidd) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom), 20 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), and 200 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (PEST; Invitrogen). HCE cells (a gift from K. Araki-Sasaki) were grown as described previously (6). HT-29 and LS 174T cells (gifts from Ya-Fang Mei) were grown according to LGC Promochem's instructions. CHO-K1 and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)-deficient CHO 13-5-1 cells (21) (gifts from David Fitzgerald), GAG-deficient pgsA-745 cells (19) (a gift from Mats Wahlgren), and GAG-deficient pgsB-618 cells (20) and the heparan sulfate-deficient cell line pgsD-677 (40) (both gifts from Magnus Evander) were all grown in Ham's F-12 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS and PEST. Species A HAdV-31 (strain 1315/63), HAdV-18 (DC), and HAdV-12 (Huie) and species C HAdV-5 (Ad75) virions were produced with or without 35S labeling in A549 cells as described previously (30), except that the virions were eluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) during desalting on a NAP column (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). To avoid the possibility that virions might be copropagated with traces of coagulation factors from the bovine calf serum present in the cell culture medium, virions were purified only from intact cells, thus preventing contact between virions and extracellular coagulation factors before the removal of the medium. Serotype-specific rabbit polyclonal antisera to the HAdVs were produced as described previously (67).

Infection experiments.

The effects of various human coagulation factors on the infection of FHs74Int cells by species A HAdVs were examined. Unlabeled virions were preincubated on ice with a purified human coagulation factor (purity, >95% as determined by the manufacturers using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [SDS-PAGE])—either FVII (Innovative Research Inc., Novi, MI), FIX (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), FX, or protein C (both from Hematologic Technologies Inc., Essex Junction, VT)—for 1 h before infection of cells. FHs74Int cells, grown as monolayers on glass slides in 24-well plates, were washed three times with serum-free medium in order to remove all traces of coagulation factors from the cell culture medium. Virion mixtures were added to the cells and were incubated for 1 h on ice. After incubation, the wells were washed three times with serum-free medium in order to remove unbound virions. A cell culture medium containing 1% FBS was added, and the plates were incubated for 44 h at 37°C. Then the glass slides were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) once, fixed with methanol, and stained with a polyclonal rabbit anti-HAdV-12 (α-HAdV-12) or anti-HAdV-31 serum diluted 1:200 for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were washed twice with PBS and were then incubated for an additional hour with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated swine anti-rabbit IgG antibody (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1:100 in PBS. After washing, the slides were mounted and examined in a fluorescence microscope (Axioskop 2; Carl Zeiss, Germany) using ×20 magnification. All coagulation factors were used at physiological concentrations: FIX at 5 μg/ml (50), FVII at 0.5 μg/ml, FX at 10 μg/ml (56), and protein C at 4 μg/ml (23). In some cases, EDTA (final concentration, 10 mM; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was included in the incubation mixture. Two hundred to 400 virions/cell were used to obtain approximately 10 infected cells/view field.

Binding experiments.

The effects of coagulation factors on the binding of species A HAdVs were determined as follows. 35S-labeled virions (2 × 109 virions in 100 μl/sample) were incubated with coagulation factors for 1 h on ice in binding buffer (BB) (DMEM supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin, PEST, and HEPES) before binding to cells. Cells were detached with EDTA, reactivated in growth medium for 1 h at 37°C (in solution), pelleted in 96-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well), and washed with BB to remove traces of coagulation factors from the growth medium. Virion mixtures were incubated with cells for 1 h on ice. Unbound virions were washed away with BB, and the cell-associated radioactivity was measured in a Wallac 1409 liquid scintillation counter (Perkin-Elmer). In some experiments, virions were preincubated for 1 h on ice with either FIX or FX and/or heparin, heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate A, chondroitin sulfate B (dermatan sulfate), or chondroitin sulfate C (Sigma-Aldrich) before incubation with cells. In some experiments, cells were preincubated for 1 h at 37°C with 1 U/ml of heparinase I (Hep I) (catalog no. H2519) or heparinase III (Hep III) (catalog no. H8891) from Flavobacterium heparinum (Sigma-Aldrich) before incubation with HAdV-31–FIX mixtures. In one experiment, the cells were preincubated with increasing concentrations of lactoferrin (Sigma-Aldrich) on ice for 1 h before the addition of HAdV-31–FIX mixtures.

Protein expression and purification.

The purified HAdV-5 hexon (purity, >95% as demonstrated by the manufacturer using SDS-PAGE) was purchased from Micromun (Greifswald, Germany). HAdV-12 and HAdV-31 hexons were produced using HAdV-12- and HAdV-31-infected A549 cells, respectively, and were purified as described previously (59). For both hexons, purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis showing a single band for each protein at 108 kDa, which is the expected size of a hexon monomer (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Analysis of the bands by mass spectrometry (data not shown) confirmed the identities of the purified proteins. All hexons were used in their native, trimeric state.

Determination of binding parameters by use of SPR.

All surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments were performed at 25°C with a Biacore 2000 instrument and a data collection rate of 1 Hz. CM5 and C1 sensor chips, an amine-coupling kit, and surfactant P20 were all purchased from GE Healthcare (Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Interactions between coagulation factors and adenovirus hexons have been shown previously to be critically dependent on the presence of Ca2+ ions (31, 32, 52, 65). We therefore used HBS-Ca2+P buffer (pH 7.4), containing 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 0.005% (vol/vol) surfactant P20, as the running buffer. Accordingly, standard HBS-EP buffer (pH 7.4), containing 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% (vol/vol) surfactant P20, was used for efficient regeneration of the chip. Multicycle kinetic (MCK) and single-cycle kinetic (SCK) experiments (33) were performed using two consecutive flow cells. HAdV-5, HAdV-12, and HAdV-31 hexons were covalently immobilized onto the surface of the downstream experimental flow cell via amine-coupling chemistry according to the manufacturer's instructions, while the surface of the upstream flow cell was subjected to the same coupling reaction in the absence of protein and was used as a reference. FIX, FX, and an anti-hexon monoclonal antibody (MAb) (MAB8052; purchased from Millipore, Billerica, MA) that is able to detect native (i.e., nondenatured) epitopes were used as soluble analytes. While we found that both the HAdV-31 hexon-FIX and the HAdV-5 hexon-FX interaction could be explained by a simple 1:1 binding event, the binding of the immobilized HAdV-5 hexon to FIX was clearly more complex. This can be appreciated by examining Fig. S2 in the supplemental material, which shows one of the data sets obtained when our results were fitted to 1:1 binding models. To the best of our knowledge, no reports exist to date that provide support for a more complex binding event between hexons and a coagulation factor. Therefore, the use of a more complex SPR model to fit the data obtained seemed unjustified. Instead, we tested a different setup, as described in reference 57. The CM5 sensor chip used formerly (a chip with a dextran matrix) was replaced by a C1 chip (a chip without a dextran matrix), and the orientations of the interaction partners (i.e., the HAdV-5 hexon and FIX) were reversed. Other parameters, such as the temperature (25°C) and flow rate (30 μl/min), remained the same. Although this altered assay setup resulted in sensorgrams with rather low response curves, these could readily be fit to a 1:1 interaction model in both multicycle and single-cycle kinetic analyses.

MCK SPR experiments.

The analytes (FIX, FX, and the HAdV-5 hexon) were serially diluted in running buffer to prepare a 2-fold concentration series and were then injected in series over the reference and experimental biosensor surfaces at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. A blank sample containing only the running buffer was also injected under the same conditions to allow for double referencing. After each cycle, the biosensor surface was regenerated with a 3-min pulse of HBS-EP at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. Double referencing was performed in two steps: First, each analyte sample response curve of the entire concentration series (i.e., of a single interaction experiment) that was obtained from the reference surface was subtracted from the simultaneously recorded response curve of the experimental surface so as to remove bulk effects. In a second step, all single referenced analyte response curves were additionally referenced by subtraction of the single referenced response curve of the running buffer sample in order to remove systematic response deviations (45). The association (on-rate) constant (ka) and the dissociation (off-rate) constant (kd), including their standard errors, were determined simultaneously by globally fitting double-referenced sensorgrams of the entire concentration series to a “1:1 binding with mass transfer, refractive index (RI) effect = 0” model with BIAevaluation software, version 4.1 (Biacore). The dissociation constant (KD) was calculated as kd/ka.

SCK SPR experiments.

The analytes (FIX, FX, and the HAdV-5 hexon) were serially diluted in running buffer to prepare 2- or 5-fold concentration series and were then titrated (injected sequentially) within a single binding cycle, in order of increasing concentration, over the reference and experimental biosensor surfaces at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. This procedure was repeated in a second cycle where, instead of the analyte, running buffer (blank) was injected to allow for double referencing, performed essentially as described in the preceding section. ka and kd were determined by fitting the double-referenced sensorgram of the titration series to a “titration kinetics 1:1 binding with drift” model with BIAevaluation software, version 4.1 (Biacore). KD was calculated as kd/ka.

Qualitative SPR binding assays.

Experiments were performed as described for multicycle kinetic experiments above. Briefly, analyte samples (FIX, FX, and an α-hexon MAb) and associated running buffer samples were injected over the same HAdV-12 or HAdV-31 biosensor surfaces, followed by qualitative evaluation of the individual binding responses of the analytes based on their corresponding double-referenced sensorgrams.

Statistical analysis.

Virus binding and infection experiments were performed three times with duplicate samples in each experiment. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD), and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's posttest was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPR interactions were analyzed twice using different experimental setups (i.e., MCK and SCK, respectively). The standard errors of the parameters presented in Table 1 and Fig. 2 and 3 were calculated by BIAevaluation software (version 4.1; Biacore) from all sensorgram response curves of the corresponding SPR data set.

Table 1.

Interaction data determined by SPR

| Ligand (immobilized) | Analyte (in solution) | Chip | Multicycle kineticsa |

Single-cycle kineticsa |

Avg affinity (KD [10−9 M]) | Avg half-life (t1/2 [s])c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD (10−9 M) | ka (M−1 s−1) | kd (s−1) | KD (10−9 M) | ka (M−1 s−1) | kd (s−1) | |||||

| HAdV-31 hexon | FIXb | CM5 | 3.3 | (8.9 ± 0.01)·104 | (2.9 ± 0.01)·10−4 | 3.4 | (9.4 ± 0.06)·104 | (3.1 ± 0.02)·10−4 | 3.4 | 2,310 |

| HAdV-5 hexon | FXb | CM5 | 5.8 | (6.2 ± 0.06)·105 | (3.6 ± 0.03)·10−3 | 6.3 | (4.5 ± 0.02)·105 | (2.8 ± 0.03)·10−3 | 6.1 | 217 |

| FIX | HAdV-5 hexon | C1 | 9.4 | (2.7 ± 0.02)·105 | (2.6 ± 0.01)·10−3 | 16.7 | (1.7 ± 0.12)·105 | (2.8 ± 0.13)·10−3 | 13.1 | 257 |

Standard errors were calculated by BIAevaluation software, version 4.1.

The physiological concentration of FX (molecular mass, 58,900 Da) in blood is 10 μg/ml (≙170 nM), and that of FIX (molecular mass, 58,700 Da) is 5 μg/ml (≙85 nM).

t1/2 = 0.693·kd−1.

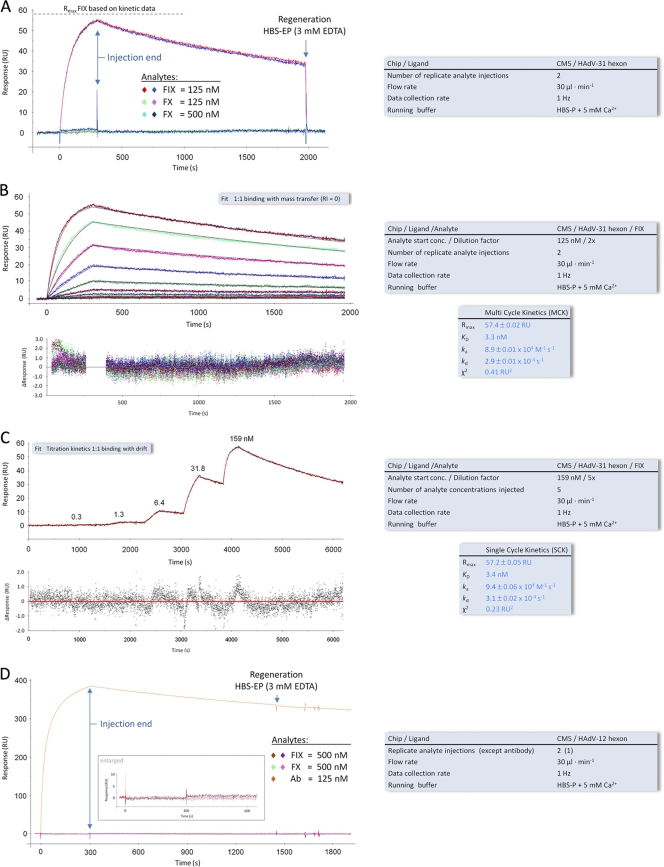

Fig. 2.

SPR analyses of the interactions of the HAdV-12 and HAdV-31 hexons with FIX and FX. (A) Binding of FIX and FX to a surface-immobilized HAdV-31 hexon. (B and C) MCK (B) and SCK (C) analyses of FIX binding to a surface-immobilized HAdV-31 hexon. Black and red lines overlying the MCK and SCK sensorgram response curves, respectively, represent the global fit of a “1:1 binding” model to each kinetic data set. Corresponding residual plots below each sensorgram show the kinetic-fit range and absolute deviation (Δ) of data points from curve fit values. (D) Binding of FIX, FX, and an anti-hexon MAb to a surface-immobilized HAdV-12 hexon. Keys to the right of each sensorgram contain additional information about the setup (black font) and measured interaction parameters (blue font). All sensorgram response curves shown were double referenced. RU, resonance units.

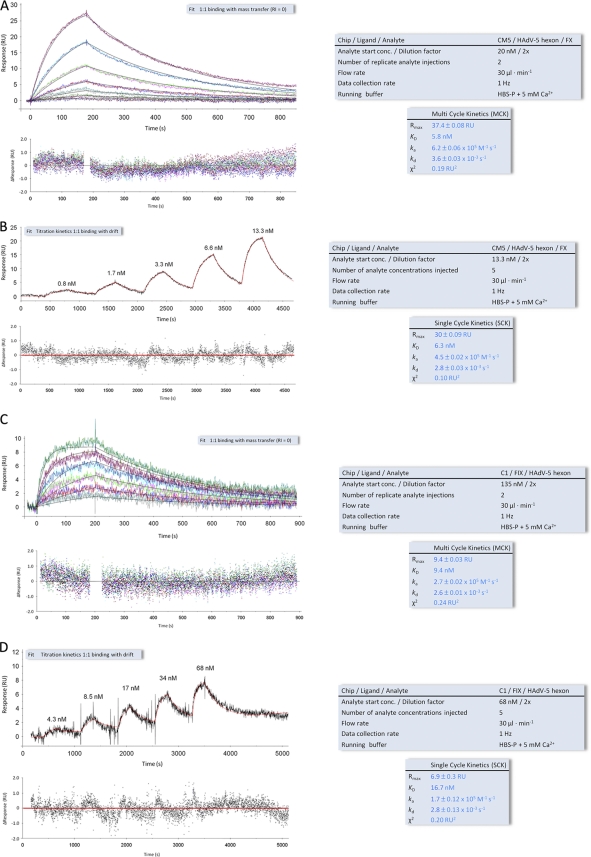

Fig. 3.

SPR analyses of the interactions of the HAdV-5 hexon with FIX and FX. (A and B) MCK (A) and SCK (B) analyses of FX binding to a surface-immobilized HAdV-5 hexon. (C and D) MCK (C) and SCK (D) analysis of HAdV-5 binding to surface-immobilized FIX. Black and red lines overlying the MCK and SCK sensorgram response curves, respectively, represent the global fit of a “1:1 binding” model to each kinetic data set. Corresponding residual plots below each sensorgram show the kinetic-fit range and absolute deviation (Δ) of data points from curve fit values. Keys to the right of each sensorgram contain additional information about the setup (black font) and measured interaction parameters (blue font). All sensorgram response curves shown were double referenced. RU, resonance units.

RESULTS

Coagulation factor IX promotes cellular binding and infection of HAdV-18 and HAdV-31, but not HAdV-12.

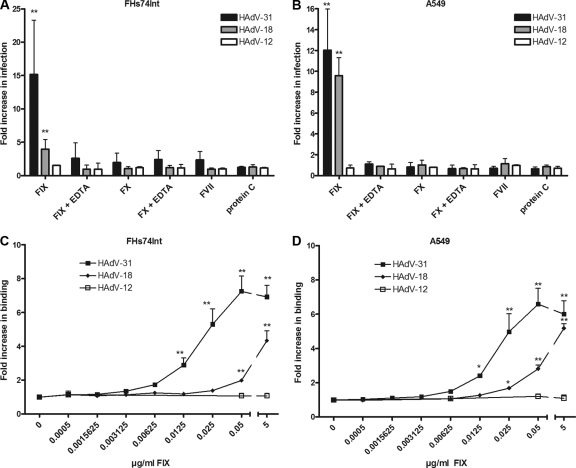

HAdV-5 is able to use FX and, to a lesser extent, FIX to enhance the efficiency of binding to and infection of target cells (31, 32, 51, 52, 62, 65, 66). We found previously that FIX, but not FX, promoted HAdV-31 binding and infection of epithelial cells, and we suggested that this mechanism may contribute to the natural course of wt HAdV-31 infections (31). To investigate whether the usage of FIX is a common feature of species A HAdVs, we preincubated virions with physiological concentrations of coagulation factors and found that only FIX promoted infection of FHs74Int and A549 cells by some species A HAdVs (Fig. 1 A and B). Increased infection was observed for HAdV-18 (4- and 9-fold, respectively) and for HAdV-31 (15- and 12-fold, respectively), but not for HAdV-12. Since the experiments were performed at a low temperature (4°C), the enhanced infection was more likely a result of more-efficient virion binding to cells than a proteolytic effect of FIX on the viral capsid, which could theoretically result in novel, direct interactions between virions and cells. The mechanism was dependent on divalent cations, since the inclusion of EDTA abrogated the promoting effect. Other coagulation factors (FX, FVII, and protein C) did not significantly affect the infection. To confirm that the increased infection was an effect of increased virion binding to cells, 35S-labeled species A HAdV virions were preincubated with (or without) FIX and were allowed to bind to FHs74Int or A549 cells. This resulted in dose-dependent increases in the binding of HAdV-18 (4- and 5-fold, respectively) and HAdV-31 (6- and 7-fold, respectively), but not of HAdV-12 (Fig. 1C and D). Notably, FIX promoted the binding of HAdV-31 more efficiently than that of HAdV-18. A marked increase in the level of HAdV-31 binding was observed at 0.05 μg/ml FIX (corresponding to 1% of the physiological concentration), whereas higher FIX concentrations were required to promote a similar level of HAdV-18 binding. FIX also promoted efficient binding of HAdV-18 and HAdV-31, but not HAdV-12, to ocular (HCE) and colon (HT-29) cell lines and weakly promoted binding to another colon cell line (LS 174T) (see Fig. S3A to C in the supplemental material). The differences in the levels of FIX-mediated enhancement of virus infection (Fig. 1A and B) and binding (Fig. 1C and D) are likely due to effects from other downstream (intracellular) factors, which are not involved in the binding step. Taken together, these results demonstrate that FIX is an efficient mediator of HAdV-18 and -31 binding to several cell types.

Fig. 1.

FIX promotes serotype-specific infection and binding of species A adenoviruses in human epithelial cells. (A and B) Effects of physiological concentrations of coagulation factors on species A adenovirus infection of FHs74Int (A) and A549 (B) cells in the presence or absence of EDTA. (C and D) Effects of increasing concentrations of FIX on species A binding to FHs74Int (C) and A549 (D) cells. The control infection/binding level (0 μg/ml coagulation factor) corresponds to the y axis value of 1. Values are means ± SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences from results for the control (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Factor IX binds with high affinity to the HAdV-31 hexon but not to the HAdV-12 hexon.

It has been suggested previously that FIX binds to the fiber knob protein of HAdV-5 (62). To evaluate the possible interaction of FIX with the HAdV-31 fiber knob, a binding experiment was conducted where excess amounts of soluble fiber knobs were added to block FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to FHs74Int cells. The addition of HAdV-31 fiber knobs did not inhibit the FIX-mediated binding of HAdV-31 to cells, indicating that the HAdV-31 fiber knob does not bind to FIX (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). It did, however, affect the basal binding (i.e., in the absence of FIX) of HAdV-31, likely due to inhibited CAR binding. It has also been shown that FX binds to HAdV-5 virions via the hexon protein (4, 65), and since FX and FIX are highly homologous (39), we next assumed that the HAdV-31–FIX interaction is also mediated by the hexon protein. To characterize FIX interactions with species A HAdV hexons in greater detail, we performed surface plasmon resonance analysis of FIX interactions with hexons from HAdV-12 (data not shown) and -31 (data summarized in Table 1 ). The HAdV-5 hexon and FX were included as controls. First, we generated an HAdV-31 hexon surface with a final hexon immobilization level of 400 resonance units (RU). An initial qualitative experiment showed that a sample containing FIX at a concentration of 125 nM produced a significant binding response, while samples containing FX at concentrations of 125 and 500 nM, respectively, did not give binding responses (Fig. 2 A). We then employed both multicycle and single-cycle kinetic experiments (Fig. 2B and C) to further characterize the parameters of binding between the HAdV-31 hexon and FIX. These experiments showed that the HAdV-31 hexon binds to FIX with an average affinity of 3 nM, more than 25-fold lower than the physiological concentration in blood (85 nM, which is equivalent to 5 μg/ml [Table 1]). Next, a CM5 sensor surface was created with 2,500 RU of the HAdV-12 hexon, and FIX or FX (concentration, 500 nM) was injected onto the biosensor surface. However, no binding response was detected (Fig. 2D). We conclude that under physiological conditions neither FIX nor FX interacts productively with the HAdV-12 hexon, for the following reasons: (i) we observed a high response with an anti-hexon MAb (Fig. 2D), indicating that the hexon surface is active; (ii) gel filtration analysis indicated proper trimerization and folding of the HAdV-12 hexon protein (data not shown); (iii) the concentration of FIX or FX added in solution (500 nM) exceeds the respective physiological concentration of each protein (Table 1); and (iv) both FIX and FX interacted with immobilized HAdV-5 (see Fig. 3; also below), and FIX interacted with HAdV-31 hexons (Fig. 2A to C), thus proving that these proteins (FIX and FX) function properly. We cannot rule out the possibility that FIX and FX bind the HAdV-12 hexon with micromolar affinity. However, such an interaction is unlikely to be biologically relevant, since the physiological concentrations (in blood) of these coagulation factors never reach micromolar levels.

To compare the HAdV-31 hexon-FIX binding parameters with those of the HAdV-5 hexon-FIX/FX interactions (32, 65), we created two surfaces (see Materials and Methods for details): one HAdV-5 hexon surface to probe for FX binding (Fig. 3 A and B) and one FIX surface to probe for HAdV-5 hexon binding (Fig. 3C and D). The average KD, determined from multicycle and single-cycle kinetic experiments (Fig. 3A to D), was 6 nM for the HAdV-5 hexon-FX interaction and 13 nM for the HAdV-5 hexon-FIX interaction (summarized in Table 1). These KD values are 28-fold (FX) and 7-fold (FIX) below the physiological concentrations of these coagulation factors in blood (170 nM for FX and 85 nM for FX). Notable from the SPR data was the slow off-rate constant (kd) of the HAdV-31 hexon-FIX interaction (3 × 10−4 s−1 [Table 1]), reflecting the stability of the complex, which can also be expressed as the complex's half-life (t1/2, calculated as 0.693·kd−1), 2,310 s (Table 1). The half-lives of the HAdV-5 hexon-FIX and HAdV-5 hexon-FX complexes were calculated accordingly and were found to be 257 and 217 s, respectively (Table 1). This clearly shows that the HAdV-31 hexon-FIX interaction is the most stable of the three interactions tested in this study. Moreover, all three complexes feature half-lives significantly higher than the half-lives of complexes such as the HAdV-11 knob-CD46 (t1/2, 46 s) or the HAdV-35 knob-CD46 (t1/2, 20 s) complex (16), which have been shown to allow for productive adenovirus infection of CD46-expressing cells (42). The HAdV-31 hexon-FIX complex also has a longer half-life than the HAdV-5 knob-CAR complex (t1/2, 686 s) (34).

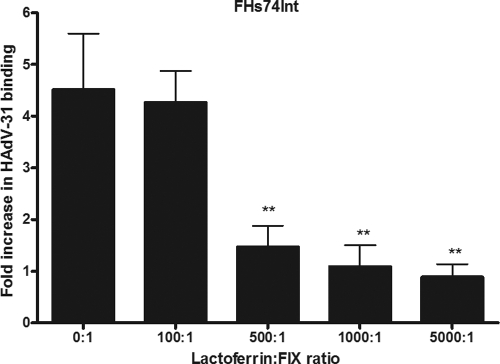

Lactoferrin inhibits FIX-mediated binding of HAdV-31 virions to FHs74Int cells.

It has been suggested previously that FIX- and FX-mediated binding of HAdV-5 to cells in vitro and in vivo depends on either cell surface heparan sulfate or low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP), or both (3, 13, 31–32, 52, 62, 65). Activated FIX (FIXa), but not FIX, has also been shown to bind directly to cellular LRP (46). To test if these receptors were involved in FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding, we used human lactoferrin, a component of the innate immune defense that is known to bind to heparan sulfate, LRP, and some other cellular receptors (27, 73). FHs74Int cells were preincubated with increasing concentrations of lactoferrin before the addition of HAdV-31 virions that had been preincubated with a low concentration of FIX (0.05 μg/ml) in order to optimize the potentially inhibitory effect of lactoferrin. As expected, lactoferrin inhibited FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4), but not basal binding (i.e., in the absence of FIX) (data not shown). This indicated that FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding could be dependent on either heparan sulfate or LRP, or both. We cannot, however, exclude interactions with additional lactoferrin receptors.

Fig. 4.

Lactoferrin inhibits FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to FHs74Int cells in a dose-dependent manner. The effect of increasing lactoferrin concentrations on FIX-mediated binding of HAdV-31 to FHs74Int cells is shown. The control binding level (0 μg/ml FIX) corresponds to the y axis value of 1. Values are means ± SD. Double asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.01) from the control.

FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding requires cell surface glycosaminoglycans but not LRP.

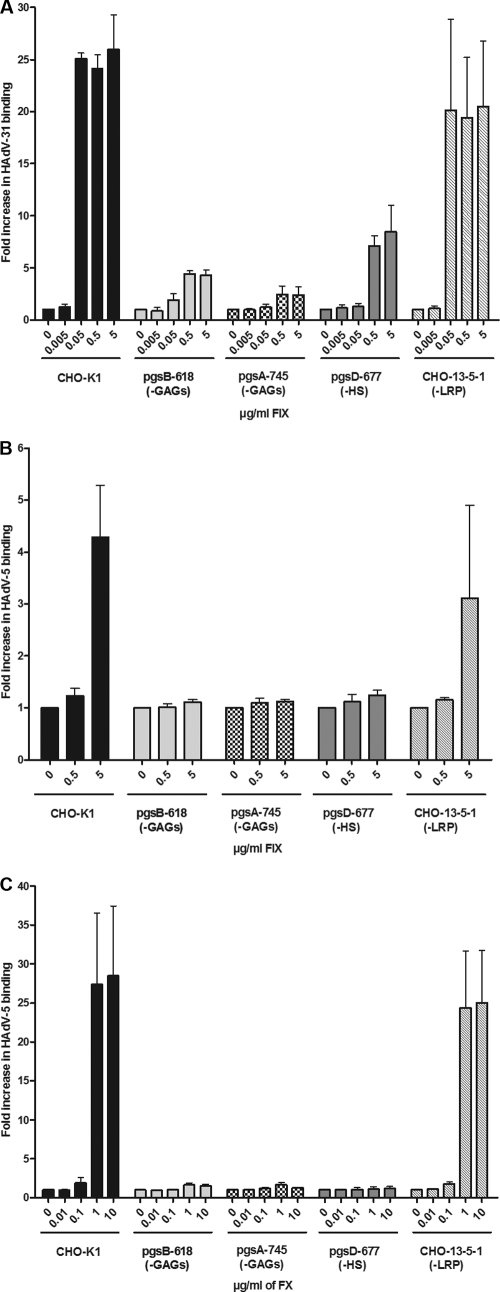

In order to further evaluate the relative roles of heparan sulfate and/or LRP during FIX-mediated binding of HAdV-31 virions, we used a set of CHO cells with different receptor expression and quantified FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding. FIX efficiently promoted HAdV-31 binding to control CHO-K1 cells expressing high basal levels of GAGs and LRP, as well as to CHO-13-5-1 cells, which lack endogenous (hamster) LRP (Fig. 5 A). FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to cells lacking heparan sulfate (psgD-677) was less pronounced, however, and binding was much less efficient when the cells lacked all GAGs (pgsB-618 and pgsA-745). Since human FIXa has the ability to bind to hamster LRP (46), and since FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to FHs74Int cells was not inhibited by an excess of known LRP ligands, such as plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, receptor-associated protein, or α2-macroglobulin (data not shown), we concluded that LRP is not important for FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to these cells. Further, both FIX and FX efficiently promoted HAdV-5 binding to CHO-K1 and CHO-13-5-1 cells, but no promoting effect was observed when GAG- or heparan sulfate-deficient cells were used, as expected (Fig. 5B and C, respectively). We noted that, whereas physiological concentrations of FIX (5 μg/ml) were required to promote HAdV-5 binding to CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 5B), only 1% of the physiological FIX concentration was sufficient to promote HAdV-31 binding (Fig. 5A). Thus, these results suggest that GAGs in general, and heparan sulfate in particular, but not LRP, are important for FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to cells.

Fig. 5.

FIX-mediated cellular binding of HAdV-31 requires cell surface heparan sulfate. The effects of FIX (A and B) or FX (C) on the binding of HAdV-31 (A) or HAdV-5 (B and C) to CHO cells expressing (CHO-K1) or lacking various glycosaminoglycans (pgsB-618, pgsA-745, and pgsD-677) or LRP (CHO-13-5-1) are shown. The control binding level (0 μg/ml FIX or FX) corresponds to the y axis value of 1. Values are means ± SD.

Heparin and heparan sulfate are efficient inhibitors of FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding.

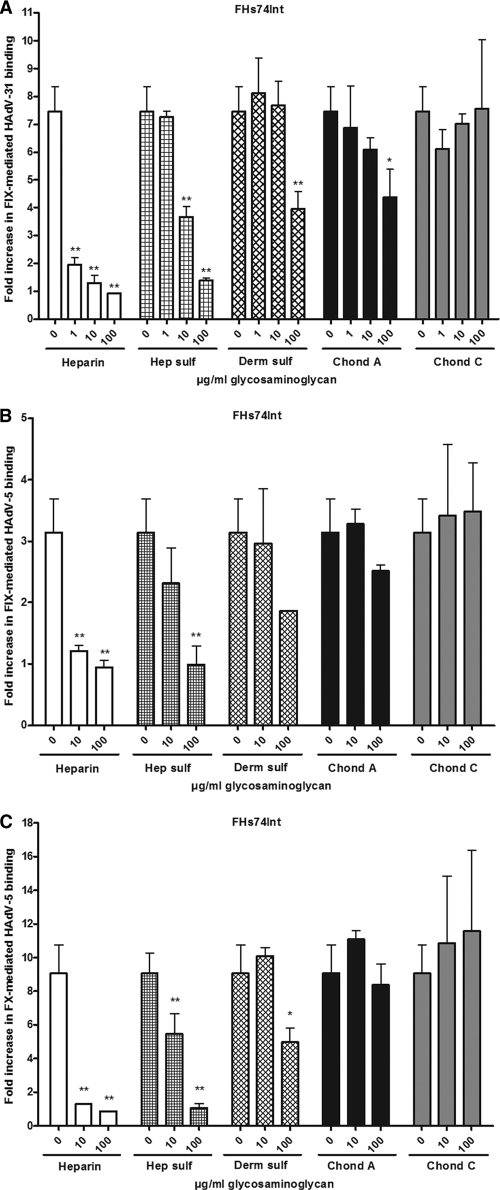

To investigate the relative roles of specific GAGs in more detail, 35S-labeled HAdV-31 and HAdV-5 virions were preincubated with FIX or FX in the presence of increasing concentrations of soluble GAGs (Fig. 6 A to C). None of the GAGs used affected basal virion binding (data not shown). Heparin and heparan sulfate each outcompeted FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding efficiently (Fig. 6A). Dermatan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate A also inhibited the binding, but not to the same extent and only at the highest concentration used (100 μg/ml). Even at the highest concentration, chondroitin sulfate C failed to show an inhibitory effect. As expected, heparin and heparan sulfate also inhibited FIX- and FX-mediated HAdV-5 binding most efficiently. These results indicate that heparan sulfate is the most important GAG used for FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding.

Fig. 6.

Heparin and heparan sulfate efficiently reduce FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding. The inhibitory effects of soluble GAGs on FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding (0.05 μg/ml FIX) (A), FIX-mediated HAdV-5 binding (5 μg/ml FIX) (B), or FX-mediated HAdV-5 binding (1 μg/ml FX) (C) to FHs74Int cells are shown. The concentrations of GAGs are given in micrograms per milliliter, since the molecular weights of these compounds are not precisely determined by the supplier and may differ within (and between) preparations. The average molecular masses of the substances used are, however, relatively similar (10 to 20 kDa) except for chondroitin sulfate C (50 to 60 kDa). The control binding level (0 μg/ml FIX or FX) corresponds to the y axis value of 1. Values are means ± SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the control (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). Hep sulf, heparan sulfate; Derm sulf, dermatan sulfate; Chond A, chondroitin sulfate A; Chond C, chondroitin sulfate C.

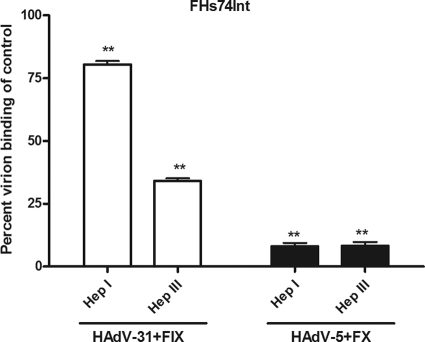

FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding is inhibited by Hep III but not by Hep I.

It has been shown previously that treatment of host cells with heparinase I (Hep I) efficiently prevents FX-mediated binding of HAdV-5 to target cells (31, 62). In agreement with this, we found here that FX did not promote HAdV-5 binding to FHs74Int cells that were pretreated with Hep I (Fig. 7). However, only a small effect of Hep I treatment on FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding was observed. Hep I cleaves mainly glycosidic bonds in regions that are highly sulfated and cleaves specifically between GlcNSO4 and 2-O-sulfated iduronic acid (IdoA2S), which are not common in heparan sulfate (26, 41, 53). Also, Hep I does not cleave the domains of heparan sulfate that are in proximity to the protein backbone (the N-acetylated domains and transition zones), which are less sulfated. These regions, however, are cleaved by heparinase III (Hep III), which cleaves specifically between uronic acids (iduronic acid [IdoA] or glucuronic acid [GlcA]) and N-sulfated or N-acetylated glucosamine (GlcNSO4 and GlcNAc, respectively) (17, 70). These motifs are relatively common in heparan sulfate, and therefore, Hep III cleaves heparan sulfate more efficiently than Hep I (70). As expected, we found that Hep III treatment of FHs74Int cells efficiently prevented FX-mediated HAdV-5 binding, but FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding was also efficiently reduced. Taken together, these results demonstrate that FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to host cells requires heparan sulfate, but they also indicate that the HAdV-31–FIX complex binds to heparan sulfate domains that are less sulfated and more N-acetylated than those bound by the HAdV-5-FX complex.

Fig. 7.

Heparinase III, but not heparinase I, inhibits FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to FHs74Int cells. The effects of heparinase I and heparinase III on FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding and FX-mediated HAdV-5 binding to FHs74Int cells are shown side by side. The control binding level (0 μg/ml FIX or FX) corresponds to the y axis value of 1. Values are means ± SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01) from the control.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that FIX is a mediator of species A HAdV-18 and HAdV-31 binding to and infection of human epithelial cells. The HAdV-31 hexon-FIX interaction exhibits higher affinity (2-fold) and a longer half-life (11-fold) than the HAdV-5 hexon-FX interaction. Moreover, both complexes (HAdV-31–FIX and HAdV-5–FX) bind to cell surface glycosaminoglycans, but whereas cellular binding of the HAdV-5–FX complex is less cryptic and involves heparan sulfate only, the binding of the HAdV-31–FIX complex to host cells is more intricate and appears to involve other cell surface components in addition to heparan sulfate.

Overall, our study provides strong evidence that FIX, but not FX, is an efficient mediator of two of the three species A HAdVs (i.e., HAdV-18 and HAdV-31). Binding and infection experiments clearly demonstrated that FIX promotes virus binding to and infection of cells representing the intestinal and respiratory tropism of species A HAdVs. In all experiments, FIX promoted binding and infection by HAdV-31 more efficiently than those by HAdV-18, and no effect, or a very small effect, of FIX was observed for HAdV-12. This difference is likely due to the differences in affinity between FIX and the hexon proteins of HAdV-31 (3 nM) and HAdV-12 (>500 nM). Since the physiological concentration of FIX in plasma is only 85 nM, our results suggest that HAdV-12 either binds directly to host cells or uses another soluble component for indirect binding. Infection experiments and SPR analyses excluded the possibility that FVII, FX, and protein C, which, like FIX, also belong to the protein family of vitamin K-dependent zymogens, are used by HAdV-12. The determinants of the greater efficiency of FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding/infection than of FIX-mediated HAdV-18 infection were less obvious. The hexons of HAdV-18 and HAdV-31 are more homologous to each other than to the HAdV-12 hexon, but differences in the hexons of these two viruses can still affect the binding parameters of the respective FIX interaction. Moreover, in our in vitro binding systems, where we use nonpolarized cells, the relative impact of FIX may also depend on the ability of each virus to interact with cell surface CAR and/or with other cellular receptors. Currently, among the three species A HAdVs, only the binding of the HAdV-12 fiber knob to CAR has been structurally (12) and functionally (34) evaluated. The level of CAR binding probably reflects the differences in basal binding (in the absence of FIX) to cells and thereby also the relative effect of FIX. In agreement with this, we noted that high basal binding of HAdV-31 (to LS 174T cells) (data not shown) correlated with a weak effect of FIX (<3-fold-increased binding [see Fig. S3C in the supplemental material]) and that low basal binding of HAdV-31 (to HCE cells) (data not shown) correlated with a strong effect of FIX (>18-fold-increased binding [see Fig. S3A]). Similar results have been observed by others, but with two types of pancreatic cell lines (24). A common feature of FX and FIX interactions with HAdVs, however, is that divalent cations are required, as evidenced by the fact that each interaction is highly sensitive to EDTA. Other structurally related coagulation factors evaluated in this study (FVII, FX, and protein C) did not promote infection by any of the species A HAdVs, thus emphasizing the specific use of FIX by HAdV-18 and HAdV-31. However, HAdV-18 has been shown previously to bind weakly to FX, which somewhat contradicts our findings (65). On the other hand, in the same publication, the investigators showed that HAdV-35 bound to FX at the same level as HAdV-18 but that HAdV-35 transduction of Hep2 cells was not affected by FX. This suggests that FX exerts an effect on HAdV infection/transduction only if the binding to the capsid is strong enough. Here, the HAdV-18 interaction with FX is apparently not strong enough to result in enhanced infection.

In this work, we also observed some remarkable differences between the abilities of HAdV-31 and HAdV-5 to utilize coagulation factors for binding to target cells. First, whereas HAdV-5 used either FIX or FX for enhanced cellular binding, HAdV-31 used only FIX. Second, the affinity of the HAdV-31-FIX interaction was higher than the affinities of the HAdV-5–FIX/FX interactions, and perhaps more strikingly, the HAdV-31–FIX complex exhibited a half-life (2,310 s) significantly (9- to 11-fold) longer than those of the HAdV-5–FIX (257 s) and HAdV-5–FX (217 s) complexes.

Third, whereas FIX and FX did not promote HAdV-5 binding to GAG- or heparan sulfate-deficient CHO cell lines, FIX mediated reduced but significant HAdV-31 binding to heparan sulfate-deficient cells, and even further reduced (but not abolished) binding to GAG-deficient cells. This indicated that other GAGs besides heparan sulfate may, to some extent, contribute to FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding. However, when the inhibitory effects of selected soluble GAGs were examined, small effects were observed only at the highest concentrations of dermatan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate A. These effects are probably less important than the effects of heparin and heparan sulfate. Also, we observed no effects on FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding after treating the cells with chondroitinase ABC (data not shown). From these experiments, we could not pinpoint any specific GAG besides heparan sulfate as important during HAdV–FX/FIX binding. LRP has been suggested by others to function as a receptor for HAdV-5-coagulation factor complexes, but we ruled out LRP as a receptor for the HAdV-31-FIX complex, because FIX promoted the binding of HAdV-31 virions to CHO cells lacking endogenous LRP expression, and because LRP ligands failed to block FIX-mediated HAdV-31 binding to cells expressing human LRP. Pretreatment of FHs74Int cells with heparinases provided further support for mechanistic differences in the cellular interactions of the HAdV-5–FX and the HAdV-31–FIX complexes. Hep I treatment, which preferentially cleaves highly sulfated heparin GAGs containing GlcNSO4 and IdoA2S units, efficiently decreased the binding of HAdV-5 but not that of HAdV-31. On the other hand, heparinase III treatment, which cleaves less sulfated heparan sulfate containing uronic acids (IdoA or GlcA) and GlcNSO4 or GlcNAc, efficiently reduced the binding of both complexes. Thus, since heparan sulfate (but not heparin) is directly linked to the cell surface, these results suggested that the heparan sulfate GAG is an important cellular receptor for the HAdV-31–FIX complex on human epithelial cells. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other molecules may also contribute to some extent to HAdV-31–FIX binding. The longer half-life of the HAdV-31–FIX complex than of the HAdV-5–FIX/FX complexes could make the former less sensitive to decreased amounts of heparan sulfate on the cell surface and could also contribute to the different binding levels obtained by treatment with heparinases I and III. The results of the heparinase experiments also suggested that the binding of the HAdV-31–FIX complex to heparan sulfate on the cell surface is more specific than the binding of the HAdV-5-FX complex, in that the HAdV-31–FIX complex prefers less sulfated domains that are also rich in GlcA and GlcNAc units. The HAdV-5–FX complex, on the other hand, bound to all types of heparan sulfate equally well. It was shown recently that the HAdV-5–human FX complex bound to heparan sulfate proteoglycans with higher affinity than HAdV-5–mouse FX (75), providing further support for mechanistic differences not only in the interactions between HAdV hexons and coagulation factors, but also in those between different types of HAdV-factor complexes and the heparan sulfate receptors.

In conclusion, there are more determinants of coagulation factor-mediated binding of HAdV to host cell molecules than previously recognized. Whereas FX appears to bind efficiently to a significant but still limited number of HAdV types (65), our study demonstrates that other soluble components influence the tropism of HAdVs other than HAdV-5. This is particularly important in view of the fact that HAdV-based gene and cancer therapy vectors other than HAdV-5 are currently being explored (1, 36, 43). Besides FIX and FX, which have been the focus of this study, lactoferrin (28) and dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC) (9) may also contribute to the tropism and in vivo targeting of HAdV-based vectors. Thus, these molecules and the corresponding HAdV interactions require more intensive studies in order to obtain a complete picture of the attachment mechanisms that regulate the tropism of wild-type HAdVs and HAdV-based vectors. In fact, adenoviruses may have evolved toward the utilization of several different soluble components that may contribute to infection depending on availability and tissue type. Coagulation factors are found mainly in blood but can also be exuded into the respiratory mucosa (55) or directly produced and secreted by bronchial cells (54), although their concentrations in the respiratory tract are unknown (49). The affinity of the HAdV-31–FIX interaction (3 nM) is much lower than the physiological concentration of FIX in plasma (85 nM), and only 1% of the physiological FIX concentration is sufficient for efficient promotion of HAdV-31 binding, suggesting that coagulation factors might regulate the binding and tropism of wild-type HAdVs and HAdV-based vectors even in the absence of blood.

These findings suggest that in addition to FX, it could be valuable to determine the impact of other body fluid factors when one is considering new HAdV serotypes to be used as alternative vectors for gene or cancer therapy. Moreover, while adenoviruses are the most popular vectors used in gene and cancer therapy clinical trials, they may also cause severe infections in humans. Species A HAdVs in general cause respiratory and intestinal infections in immunocompetent individuals, and HAdV-31 in particular appears to be an important/lethal pathogen in immunocompromised patients (25). The clinical impact of species A HAdV infections is growing with accumulating numbers of immunocompromised patients, and there is an urgent need for better understanding of the life cycle of these HAdVs and for the subsequent identification of targets for novel antiviral drugs. The high-affinity interaction between FIX and the HAdV-31 hexon may constitute such a target.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2007-3402; to N.A.), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (F06-0011; to N.A.), the Swedish Society of Medicine (SLS-97031; to N.A.), the Umeå University Biotechnology grant (223-4009-08; to N.A.), and by the Young Researcher award (223-514-09; to N.A.), the Kempe Foundation (SMK-2818; to N.A.), and the German Research Foundation (SFB685; to T.S.).

We thank David Fitzgerald, NIH, for providing CHO-K1 and CHO-13-5-1 cells; Magnus Evander, Umeå University, for providing pgsB-618 and pgsD-677 cells; Jeffrey Esko, University of California, and Mats Wahlgren, Karolinska Institutet, for providing pgsA-745 cells; Ya-Fang Mei, Umeå University, for providing HT-29 and LS 174T cells; David Persson for providing HAdV-31 fiber knobs; and Kristina Lindman for technical support.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abbink P., et al. 2007. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J. Virol. 81:4654–4663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adrian T., Wigand R. 1989. Genome type analysis of adenovirus 31, a potential causative agent of infants' enteritis. Arch. Virol. 105:81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alba R., et al. 16. June 2011. Coagulation factor X mediates adenovirus type 5 liver gene transfer in non-human primates (Microcebus murinus). Gene Ther. doi:10.1038/gt.2011.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alba R., et al. 2009. Identification of coagulation factor (F)X binding sites on the adenovirus serotype 5 hexon: effect of mutagenesis on FX interactions and gene transfer. Blood 114:965–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Albinsson B., Kidd A. H. 1999. Adenovirus type 41 lacks an RGD αv-integrin binding motif on the penton base and undergoes delayed uptake in A549 cells. Virus Res. 64:125–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Araki-Sasaki K., et al. 1995. An SV40-immortalized human corneal epithelial cell line and its characterization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 36:614–621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arnberg N., Edlund K., Kidd A. H., Wadell G. 2000. Adenovirus type 37 uses sialic acid as a cellular receptor. J. Virol. 74:42–48 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnberg N., Kidd A. H., Edlund K., Olfat F., Wadell G. 2000. Initial interactions of subgenus D adenoviruses with A549 cellular receptors: sialic acid versus αv integrins. J. Virol. 74:7691–7693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balakireva L., Schoehn G., Thouvenin E., Chroboczek J. 2003. Binding of adenovirus capsid to dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine provides a novel pathway for virus entry. J. Virol. 77:4858–4866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Belin M. T., Boulanger P. 1993. Involvement of cellular adhesion sequences in the attachment of adenovirus to the HeLa cell surface. J. Gen. Virol. 74:1485–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergelson J. M., et al. 1997. Isolation of a common receptor for coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 275:1320–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bewley M. C., Springer K., Zhang Y. B., Freimuth P., Flanagan J. M. 1999. Structural analysis of the mechanism of adenovirus binding to its human cellular receptor, CAR. Science 286:1579–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bradshaw A. C., et al. 2010. Requirements for receptor engagement during infection by adenovirus complexed with blood coagulation factor X. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown M. 1990. Laboratory identification of adenoviruses associated with gastroenteritis in Canada from 1983 to 1986. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1525–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corjon S., et al. 2011. Cell entry and trafficking of human adenovirus bound to blood factor X is determined by the fiber serotype and not hexon:heparan sulfate interaction. PLoS One 6:e18205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cupelli K., et al. 2010. Structure of adenovirus type 21 knob in complex with CD46 reveals key differences in receptor contacts among species B adenoviruses. J. Virol. 84:3189–3200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Desai U. R., Wang H. M., Linhardt R. J. 1993. Specificity studies on the heparin lyases from Flavobacterium heparinum. Biochemistry 32:8140–8145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Echavarria M. 2004. Adenoviruses, p. 343–360 In Zuckerman A. J., Banatvala J. E., Pattison J. R., Griffiths P. D., Schoub B. D. (ed.), Principles and practice of clinical virology, 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., West Sussex, England [Google Scholar]

- 19. Esko J. D., Stewart T. E., Taylor W. H. 1985. Animal cell mutants defective in glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82:3197–3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Esko J. D., et al. 1987. Inhibition of chondroitin and heparan sulfate biosynthesis in Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants defective in galactosyltransferase I. J. Biol. Chem. 262:12189–12195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. FitzGerald D. J., et al. 1995. Pseudomonas exotoxin-mediated selection yields cells with altered expression of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J. Cell Biol. 129:1533–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gaggar A., Shayakhmetov D. M., Lieber A. 2003. CD46 is a cellular receptor for group B adenoviruses. Nat. Med. 9:1408–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Griffin J. H., Mosher D. F., Zimmerman T. S., Kleiss A. J. 1982. Protein C, an antithrombotic protein, is reduced in hospitalized patients with intravascular coagulation. Blood 60:261–264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamdan S., et al. 2011. The roles of cell surface attachment molecules and coagulation Factor X in adenovirus 5-mediated gene transfer in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 18:478–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hierholzer J. C. 1992. Adenoviruses in the immunocompromised host. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 5:262–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hovingh P., Linker A. 1970. The enzymatic degradation of heparin and heparitin sulfate. 3. Purification of a heparitinase and a heparinase from flavobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 245:6170–6175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ji Z. S., Mahley R. W. 1994. Lactoferrin binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans and the LDL receptor-related protein. Further evidence supporting the importance of direct binding of remnant lipoproteins to HSPG. Arterioscler. Thromb. 14:2025–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johansson C., et al. 2007. Adenoviruses use lactoferrin as a bridge for CAR-independent binding to and infection of epithelial cells. J. Virol. 81:954–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johansson M. E., et al. 1991. Genome analysis of adenovirus type 31 strains from immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. J. Infect. Dis. 163:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johansson S. M., et al. 2007. Multivalent sialic acid conjugates inhibit adenovirus type 37 from binding to and infecting human corneal epithelial cells. Antiviral Res. 73:92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jonsson M. I., et al. 2009. Coagulation factors IX and X enhance binding and infection of adenovirus types 5 and 31 in human epithelial cells. J. Virol. 83:3816–3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kalyuzhniy O., et al. 2008. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon is critical for virus infection of hepatocytes in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:5483–5488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karlsson R., Katsamba P. S., Nordin H., Pol E., Myszka D. G. 2006. Analyzing a kinetic titration series using affinity biosensors. Anal. Biochem. 349:136–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kirby I., et al. 2001. Adenovirus type 9 fiber knob binds to the coxsackie B virus-adenovirus receptor (CAR) with lower affinity than fiber knobs of other CAR-binding adenovirus serotypes. J. Virol. 75:7210–7214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kojaoghlanian T., Flomenberg P., Horwitz M. S. 2003. The impact of adenovirus infection on the immunocompromised host. Rev. Med. Virol. 13:155–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lemiale F., et al. 2007. Novel adenovirus vaccine vectors based on the enteric-tropic serotype 41. Vaccine 25:2074–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lenaerts L., De Clercq E., Naesens L. 2008. Clinical features and treatment of adenovirus infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 18:357–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leruez-Ville M., et al. 2006. Description of an adenovirus A31 outbreak in a paediatric haematology unit. Bone Marrow Transplant. 38:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leytus S. P., Foster D. C., Kurachi K., Davie E. W. 1986. Gene for human factor X: a blood coagulation factor whose gene organization is essentially identical with that of factor IX and protein C. Biochemistry 25:5098–5102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lidholt K., et al. 1992. A single mutation affects both N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase and glucuronosyltransferase activities in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant defective in heparan sulfate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:2267–2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Linker A., Sampson P. 1960. The enzymic degradation of heparitin sulfate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 43:366–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marttila M., et al. 2005. CD46 is a cellular receptor for all species B adenoviruses except types 3 and 7. J. Virol. 79:14429–14436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mastrangeli A., et al. 1996. “Sero-switch” adenovirus-mediated in vivo gene transfer: circumvention of anti-adenovirus humoral immune defenses against repeat adenovirus vector administration by changing the adenovirus serotype. Hum. Gene Ther. 7:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mathias P., Galleno M., Nemerow G. R. 1998. Interactions of soluble recombinant integrin αv β5 with human adenoviruses. J. Virol. 72:8669–8675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Myszka D. G. 1999. Improving biosensor analysis. J. Mol. Recognit. 12:279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Neels J. G., et al. 2000. Activation of factor IX zymogen results in exposure of a binding site for low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Blood 96:3459–3465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nilsson E. C., et al. 2011. The GD1a glycan is a cellular receptor for adenoviruses causing epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Nat. Med. 17:105–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Noel J., et al. 1994. Identification of adenoviruses in faeces from patients with diarrhoea at the hospitals for sick children, London, 1989-1992. J. Med. Virol. 43:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nour-Eldin F. 1964. In vivo and in vitro behavior of clotting factors in blood and tissues. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 105:985–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Osterud B., Bouma B. N., Griffin J. H. 1978. Human blood coagulation factor IX. Purification, properties, and mechanism of activation by activated factor XI. J. Biol. Chem. 253:5946–5951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Parker A. L., et al. 2007. Influence of coagulation factor zymogens on the infectivity of adenoviruses pseudotyped with fibers from subgroup D. J. Virol. 81:3627–3631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Parker A. L., et al. 2006. Multiple vitamin K-dependent coagulation zymogens promote adenovirus-mediated gene delivery to hepatocytes. Blood 108:2554–2561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perlin A. S., Mackie D. M., Dietrich C. P. 1971. Evidence for a (1 leads to 4)-linked 4-O-(-l-idopyranosyluronic acid 2-sulfate)-(2-deoxy-2-sulfoamino-d-glucopyranosyl 6-sulfate) sequence in heparin. Long-range H-H coupling in 4-deoxy-hex-4-enopyranosides. Carbohydr. Res. 18:185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Perrio M. J., Ewen D., Trevethick M. A., Salmon G. P., Shute J. K. 2007. Fibrin formation by wounded bronchial epithelial cell layers in vitro is essential for normal epithelial repair and independent of plasma proteins. Clin. Exp. Allergy 37:1688–1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Persson C. G., et al. 1991. Plasma exudation as a first line respiratory mucosal defence. Clin. Exp. Allergy 21:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rao L. V., Rapaport S. I. 1988. Activation of factor VII bound to tissue factor: a key early step in the tissue factor pathway of blood coagulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:6687–6691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rich R. L., Myszka D. G. 2008. Survey of the year 2007 commercial optical biosensor literature. J. Mol. Recognit. 21:355–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Roelvink P. W., et al. 1998. The coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor protein can function as a cellular attachment protein for adenovirus serotypes from subgroups A, C, D, E, and F. J. Virol. 72:7909–7915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rux J. J., Burnett R. M. 2007. Large-scale purification and crystallization of adenovirus hexon. Methods Mol. Med. 131:231–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schmitz H., Wigand R., Heinrich W. 1983. Worldwide epidemiology of human adenovirus infections. Am. J. Epidemiol. 117:455–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Segerman A., et al. 2003. Adenovirus type 11 uses CD46 as a cellular receptor. J. Virol. 77:9183–9191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shayakhmetov D. M., Gaggar A., Ni S., Li Z. Y., Lieber A. 2005. Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. J. Virol. 79:7478–7491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tomko R. P., Xu R., Philipson L. 1997. HCAR and MCAR: the human and mouse cellular receptors for subgroup C adenoviruses and group B coxsackieviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:3352–3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vogels R., et al. 2003. Replication-deficient human adenovirus type 35 vectors for gene transfer and vaccination: efficient human cell infection and bypass of preexisting adenovirus immunity. J. Virol. 77:8263–8271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Waddington S. N., et al. 2008. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon mediates liver gene transfer. Cell 132:397–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Waddington S. N., et al. 2007. Targeting of adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) and 5/47 pseudotyped vectors in vivo: a fundamental involvement of coagulation factors and redundancy of CAR binding by Ad5. J. Virol. 81:9568–9571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wadell G., Allard A., Hierholzer J. C. 1999. Adenoviruses, p. 970–982 In Murray P. R., Baron E. J., Pfaller M. A., Tenover F. C., Yolken R. H. (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang H., et al. 2011. Desmoglein 2 is a receptor for adenovirus serotypes 3, 7, 11 and 14. Nat. Med. 17:96–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wang K., Guan T., Cheresh D. A., Nemerow G. R. 2000. Regulation of adenovirus membrane penetration by the cytoplasmic tail of integrin β5. J. Virol. 74:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wei Z., Lyon M., Gallagher J. T. 2005. Distinct substrate specificities of bacterial heparinases against N-unsubstituted glucosamine residues in heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 280:15742–15748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wickham T. J., Filardo E. J., Cheresh D. A., Nemerow G. R. 1994. Integrin αvβ5 selectively promotes adenovirus mediated cell membrane permeabilization. J. Cell Biol. 127:257–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wickham T. J., Mathias P., Cheresh D. A., Nemerow G. R. 1993. Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Windler E., et al. 1991. The human asialoglycoprotein receptor is a possible binding site for low-density lipoproteins and chylomicron remnants. Biochem. J. 276(Pt 1):79–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wold W. S. M., Horwitz M. S. 2007. Adenoviruses, p. 2395–2436 In Knipe D. M., et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zaiss A. K., Lawrence R., Elashoff D., Esko J. D., Herschman H. R. 2011. Differential effects of murine and human factor X on adenovirus transduction via cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 286:24535–24543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.