Abstract

LP-BM5 retrovirus induces a complex disease featuring an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome termed murine AIDS (MAIDS) in susceptible strains of mice, such as C57BL/6 (B6). CD4 T helper effector cells are required for MAIDS induction and progression of viral pathogenesis. CD8 T cells are not needed for viral pathogenesis, but rather, are essential for protection from disease in resistant strains, such as BALB/c. We have discovered an immunodominant cytolytic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitope encoded in a previously unrecognized LP-BM5 retroviral alternative (+1 nucleotide [nt]) gag translational open reading frame. CTLs specific for this cryptic gag epitope are the basis of protection from LP-BM5-induced immunodeficiency in BALB/c mice, and the inability of B6 mice to mount an anti-gag CTL response appears critical to the initiation and progression of LP-BM5-induced MAIDS. However, uninfected B6 mice primed by LP-BM5-induced tumors can generate CTL responses to an LP-BM5 retrovirus infection-associated epitope(s) that is especially prevalent on such MAIDS tumor cells, indicating the potential to mount a protective CD8 T-cell response. Here, we utilized this LP-BM5 retrovirus-induced disease system to test whether modulation of normal immune down-regulatory mechanisms can alter retroviral pathogenesis. Thus, following in vivo depletion of CD4 T regulatory (Treg) cells and/or selective interruption of PD-1 negative signaling in the CD8 T-cell compartment, retroviral pathogenesis was significantly decreased, with the combined treatment of CD4 Treg cell depletion and PD-1 blockade working in a synergistic fashion to substantially reduce the induction of MAIDS.

INTRODUCTION

The LP-BM5 murine retrovirus elicits murine AIDS (MAIDS) (3, 32, 36, 37, 42, 46–48) characterized by an early dysregulated activation of the immune system and an ensuing profound AIDS. Some important features of MAIDS resemble those of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS in humans, including (i) early-onset hypergammaglobulinemia (hyper-Ig); (ii) splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy; (iii) dependence on CD4 T cells for initiation of disease; (iv) loss of CD4 T-cell function and subsequent severely depressed T- and B-cell responses; (v) increased susceptibility to progressive infection and mortality when exposed to normally nonpathogenic microorganisms; and (vi) the development of immunodeficiency- associated “opportunistic” neoplasms, including end stage B-cell lymphomas (15, 35). While there are also some significant differences between AIDS and MAIDS, the LP-BM5 retroviral system has been widely used as a mouse model for human AIDS (3, 32, 36, 42, 46–48).

Pathogenic CD4 T effector cells are required for the initiation and progression of MAIDS, and protective CD8 T effector cells are required for MAIDS resistance (28, 44, 45, 54, 55, 58). CD8 cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTLs) play a critical role in elimination of virus-infected cells and disease control in several retroviral infections, including murine AIDS (in resistant strains) and human HIV-1 infection. Our laboratory has defined the cellular and molecular bases of CD8 CTL-mediated protection in MAIDS-resistant mouse strains (e.g., BALB/c) (28, 44, 45, 54, 55, 58), as well as insights into the requirement for CD4 T effector cell-mediated initiation/progression of viral pathogenesis in the prototypic MAIDS-susceptible strain, C57BL/6 (B6) (18–23, 39, 40). Thus, interactions between B and CD4 T cells, mediated via the ligation of CD40 and CD40L (CD154), respectively, are essential for LP-BM5-dependent pathogenesis of MAIDS, both for disease induction and for early progression (20–22). Lack of LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis can be reversed by reconstituting T-cell-lacking B6.nude or B6.TCRα−/− mice with CD154+ CD4, but not CD154−/− CD4 or wild-type (wt) CD8, T cells (20–22, 39, 40, 67).

Using CD40–cytoplasmic-tail TRAF binding site mutant, transgenic, and knockout mice (18) and a panel of CD4 T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice (39), we have gained further insight into the role these pathogenic CD4 Th cells play in mediating LP-BM5 retroviral pathogenesis. However, the question of their possible epitope specificity versus their polyclonal activation consequent to LP-BM5 infection, which is well described (39), remains unclear.

In contrast, while a strong protective CD8 T-cell response occurs in MAIDS-resistant strains, such as BALB/c, the lack of comparable LP-BM5-specific CD8 CTLs appears to be crucial to the development of MAIDS in susceptible mouse strains (44, 45, 58), similar to the role that CD8 CTLs play in initially controlling HIV-1 infection (60). Thus, we first showed that in BALB/c.CD8−/− mice, LP-BM5 infection leads to the development of MAIDS. This finding strongly suggests that the ability to develop the pathogenic CD4 T-cell response upon LP-BM5 infection, and all other cellular and molecular mechanisms for MAIDS induction and progression, are present in mice of the resistant BALB/c background, as revealed in the absence of CD8 T-cell protection (28, 44, 45, 54, 55, 58). Subsequently, we demonstrated that intravenous (i.v.) adoptive transfer of pregenerated polyclonal (or cloned) BALB/c LP-BM5 gag-specific effector CD8 CTLs provides essentially complete protection from LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis in BALB/c.CD8−/− recipients (28, 54, 55), indicating that antiviral CD8 T cells are necessary and sufficient for disease resistance. Interestingly, the fine specificity of these protective BALB/c CD8 T cells is for a major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) Kd-presented peptide, SYNTGRFPPL, which is novelly derived from a previously unrecognized +1-nucleotide (nt) alternative translational open reading frame (ORF2) of the LP-BM5 gag gene (44, 45), and the protective mechanism is perforin-mediated cytolysis (54).

As is well known, T-cell responses are controlled by the balance of positive and negative regulatory pathways. Negative regulatory pathways are important to limit the development and/or effector function of effector T-cell responses for both protective and deleterious responses. Negative regulatory pathways can function through signals delivered by T regulatory (Treg) cells, immunoregulatory cytokines, and cell surface-inhibitory receptors. A subpopulation of normal CD4 T cells that expresses the interleukin-2 receptor α chain (CD25) has been defined as a suppressive, natural T regulatory (nTreg) cell population, and induced CD4 Treg (iTreg) cells have been described as a consequence of tumor growth, many infections, and other diseases. FoxP3, a member of the forkhead winged-helix protein family of transcription factors, has proved to be a specific molecular marker for Treg cells in mice and humans. CD4 Treg cell involvement has been implicated in a number of pathological processes, including cancers and infectious diseases, as well as in controlling the extent of autoimmune diseases and many other immune responses (8, 31, 51, 56, 57, 59, 63, 68). Treg cells appear to be involved in inhibiting protective CD8 CTL effector function, particularly during chronic viral diseases caused by hepatitis C virus (43), cytomegalovirus (41), and HIV-1 (1, 33, 34, 52, 65).

In two murine retroviral systems, studies have suggested the involvement of CD4 Treg cells in retroviral pathogenesis: Friend virus (FV) infection (8, 9, 68) and LP-BM5-induced MAIDS (5, 40). In the FV system, CD4 Treg cells negatively regulate antiviral CD8 T-cell responsiveness, and an acute, transient depletion of FoxP3-positive Treg cells resulted in an increased peak cytotoxic CD8 T-cell response and prevention of Treg-dependent loss of function, allowing the viral load to be significantly reduced (68). In addition, if CD4 Treg cells were transiently depleted during the chronic phase of FV infection, antiviral CD8 T cells recovered their downregulated functions, including cytokine secretion, expression of cytotoxic effector molecules, and specific cytolytic function (8).

In MAIDS, evidence was provided by Beilharz et al. (5) that LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis could be partially reduced following in vivo administration of various combinations of anti-CD25, -CTLA-4, and -GITR antibodies, thought to be reactive with CD4 Treg cells, during a specific, narrow time window post-LP-BM5 infection. However, in the latter study, rather than targeting via the Treg-specific FoxP3 molecule, the cell surface molecules used to identify Treg cells are known to also be expressed on other activated T cells. Therefore, this approach could not distinguish a blocking effect by the corresponding antibodies on Treg cells, as suggested, from a blocking or other inhibitory effect on activated pathogenic CD4 T effector cells. In addition, in our own studies examining the possible role of nTreg cells in MAIDS by adoptive-transfer experiments, using various CD4 T-cell populations as donor cells, into B6.nude recipients (and thus in the absence of CD8 T cells), we observed no (direct) effect on the extent of LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis, comparing the presence versus absence of CD4 nTreg cells (40). Nonetheless, Treg cell depletion might provide a general approach in virus-infected hosts to allow the development of acute protective T-cell immunity and long-term memory.

Similarly, functional impairment of T cells is characteristic of many chronic mouse and human viral infections, including HIV/AIDS (10, 16), due to the engagement of normal immune down-regulatory mechanisms, such as the PD-1/PD-L pathways (2, 16, 29). Negative pathways can be critical in limiting the magnitude or duration of the antiviral CD8 T-cell response. There are multiple mechanisms of downregulation that alter CD8 T-cell induction or effector function, including impaired cytokine production, decreased antigen-induced proliferation, and a generally “functionless” CD8 T-cell phenotype, which can be due to CD8 T-cell exhaustion (2, 4, 26, 27, 29, 38, 49). Potential therapeutic approaches based on manipulation of the PD-1/PD-L pathways have been shown in certain disease models (4, 26, 30, 38). Indeed, relative to retroviral pathogenesis, in vitro studies (7, 50, 62) have suggested a role for the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in the exhaustion of virus-specific CD8 T cells during HIV infection. PD-1 was upregulated on HIV-specific (7, 10) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-specific CD8 T cells (64), and the level of PD-1 expression was associated with decreased CD8 T-cell proliferation in response to in vitro stimulation with HIV antigen (7). Furthermore, in vitro blockade of PD-1 on CD8 T cells enhanced cytokine production and the proliferative capacity of antiviral CD8 T cells (7). Similarly, in the FV system, a detailed study has shown that FV-specific CD8 T cells are functionally inhibited due to the engagement of multiple inhibitory receptors, including PD-1 and Tim-3 (61). Furthermore, the combined blockade of PD-1 and Tim-3 allowed CD8 T-cell functionality to be recovered and virus control to be reestablished (61). Thus, PD-1/PD-L1 interactions may represent a critical mechanism underlying the inability of FV- and HIV-specific T cells to control viral replication and, by extension, the weak CD8 T-cell responses observed in other retroviral systems, such as the immunosuppressive LP-BM5 system in B6 mice studied here.

Consistent with the possibility that modulation of PD-1 expression might be a basis for such therapeutic intervention in MAIDS, increased PD-1 mRNA expression during LP-BM5 infection was observed by our laboratory via Affymetrix Murine Genome Array profiling (23). We compared samples obtained from uninfected mice to those from LP-BM5-infected mice at 3.5 weeks postinfection (p.i.), the most important time window for commitment to the development of MAIDS pathogenesis, based on our studies of the kinetics of the CD154/CD40 requirement (20–22). We showed by gene array that PD-1 mRNA expression increased by about 2.4-fold in unfractionated spleen cells from infected mice, as confirmed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (23). Consistent with increased mRNA for PD-1, expression of PD-L1 by gene array and initial flow cytometric analyses also indicated an LP-BM5 infection-dependent increase (23). Because PD-L1 is constitutively expressed at modest levels on most lymphoid and myeloid cells, this enhanced PD-L1 expression was most noticeably detected in terms of fluorescence intensity, with ∼70 to 100% mean increases, depending on the cell type and number of weeks p.i. (23).

As mentioned above, a strong protective LP-BM5 gag-specific CD8 T-cell response occurs in MAIDS-resistant strains, such as BALB/c, but not in susceptible B6 mice (17, 28, 44, 45, 54, 55, 58). However, we have reported that B6 mice have the potential to mount a CD8 CTL response to a cross-reactive MHC-I H-2Kb-restricted epitope(s) found on spleen cells from LP-BM5-infected mice, and especially on B6 MAIDS-associated B-cell lymphomas (11, 24, 25). Thus, MAIDS tumor-primed CD8 T-cell preparations from uninfected B6 mice could respond to in vitro restimulation by MAIDS tumor cell, or infected spleen cell, stimulators to generate strong lytic responses against MAIDS tumor targets. Although the Kb-presented epitope(s) has not been defined, and there is no evidence that it is gag encoded (24), these cross-reactive CTLs show some protection against MAIDS induction in adoptive-transfer experiments (25). Therefore, it is possible that such B6 CD8 CTLs, though initially present and inherently capable of expanding in LP-BM5-infected MAIDS-susceptible B6 mice (11, 24, 25), subsequently fail to develop and control the initiation of MAIDS and disease progression before the onset of the profound immunodeficiency of MAIDS. It may be that the B6 CD8 CTL response is not of sufficient strength early during infection and/or of sufficient duration to inhibit MAIDS pathogenesis, but rather, it normally has only limited potential as a protective antiviral response. Therefore, there might be substantial therapeutic potential to inhibit MAIDS pathogenesis via amplification of a weak protective CD8 T-cell response.

In this study, our goal was to interfere with negative regulatory pathways controlling CD8 T-cell immunity by depleting CD4 Treg cells and/or blocking the PD-1 negative signaling pathway in the protective CD8 T-cell compartment to shift the balance toward prevention of MAIDS initiation and/or progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Male B6 mice were purchased from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD), B6.TCRα−/− breeder mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). B6-backcrossed PD-1−/− breeding pairs were obtained from Jian Zhang at the Rush-Presbyterian St. Luke's Medical Center, Chicago, IL. FoxP3-GFP (on a mixed B6 × 129 background) reporter mice were previously described and were initially received from Alexander Rudensky's laboratory at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA (12–14). Derived from these mice, FoxP3-GFP mice fully backcrossed onto the B6 background (B6.FoxP3-GFP mice) were a generous gift from Mary Jo Turk, Dartmouth Medical School. These B6.FoxP3-GFP mice contain the FoxP3 knock-in FoxP3-GFP allele (encoding a green fluorescent protein [GFP] reporter gene-FoxP3 fusion construct). All mice were housed in the Dartmouth Medical School Animal Resource Center and used at 8 to 10 weeks of age. All experiments were done in compliance with a protocol approved by the Dartmouth Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

LP-BM5 virus inoculation.

LP-BM5 virus was prepared in our laboratory as previously described (18–23, 37, 39, 40). Briefly, G6 cells, cloned from SC-1 fibroblasts infected with the LP-BM5 virus, originally provided by Janet Hartley and Herbert Morse (NIH/NIAID, Bethesda, MD), were cocultured with uninfected SC-1 cells. Mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with an LP-BM5 preparation containing 5 × 104 ecotropic PFU.

Splenocyte subpopulation preparation.

Splenocyte suspensions were prepared as described previously (39, 40). For CD4 and CD8 T cells, cell suspensions from wt or PD-1−/− mice were labeled with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 paramagnetic beads (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and positively selected according to the manufacturer's protocol. For Treg-depleted CD4 T-cell populations, splenocyte suspensions from B6.FoxP3-GFP mice were first positively selected for CD4 T cells, as described above, and then the resultant CD4 T cells were sorted using a FACSstar plus with TurboSort (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA) to deplete FoxP3-GFP+ CD4 T regulatory cells. The purity of all purified cell populations was ≥98%. A suspension of 1 × 107 purified CD4 T cells (wt, Treg depleted, or PD-1−/−), together with 5 × 106 CD8 T cells (wt or PD-1−/−), was adoptively transferred (i.v.) into B6.TCRα−/− recipients. The various combinations of cell preparations used for transfer in experiments (see Fig. 3 and 4) are listed in Table 1. The recipients were either infected with LP-BM5 48 h after adoptive transfer or used as uninfected controls.

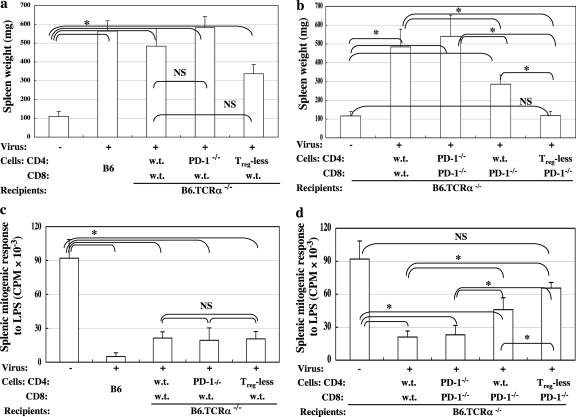

Fig. 3.

Combined adoptive transfer of Treg-deficient CD4 T cells and/or B6.PD-1−/− CD8 T cells results in a significant reduction of LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis. B6.TCRα−/− recipients were adoptively transferred with 1 × 107 unfractionated or FoxP3-GFP Treg-depleted CD4 T cells from B6.FoxP3-GFP donor mice, together with 5 × 106 CD8 T cells from either wt B6 (a and c) or wt versus B6.PD-1−/− (b and d) donors. Forty-eight hours later, a portion of the recipients were infected with LP-BM5 retrovirus. Disease was assessed at 10 weeks p.i. by the standard panel of MAIDS readouts. The data shown reflect two disease parameters: spleen weight (a and b) and immunodeficiency status as measured by the mitogenic response to LPS (c and d), with all the other disease readouts in agreement. Statistical analyses were performed between infected groups or compared to uninfected control mice. Three or more mice were used per group. NS, P ≥ 0.05, and *, P < 0.05. The data are representative of a total of three experiments, which showed similar patterns of results. The error bars indicate SD.

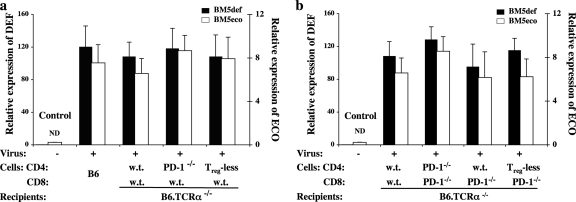

Fig. 4.

Significantly decreased viral pathogenesis in the combined-treatment group does not correlate with a reduction in the terminal viral load. The RNA expression levels of the BM5def and BM5eco viruses were determined by separate real-time qRT-PCR assays with normalization to the expression of β-actin, as we have previously reported (6). Shown are representative data for BM5def and BM5eco virus expression of the mouse groups from the experiment depicted in Fig. 3. The data depicted represent the means and standard deviations of three independent replicate assessments of each sample (each assessment was based on duplicate determinations); the control, uninfected groups showed a nondetectable (ND) level of retroviral expression; the significant levels of viral load among all infected groups were not significantly different.

Table 1.

Various combinations of sources of cell preparations and donor mice used to transfer into B6.TCRα−/− recipientsa

| Figure | Experimental group | CD4 T cells | Donor mouse for CD4 T cells | CD8 T cells | Donor mouse for CD8 T cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a and 5a | 1 (control)b | B6 and PD-1−/− | B6, B6.FoxP3-GFP, and B6.PD-1−/− | B6 and PD-1−/− | B6 and B6.PD-1−/− |

| 2 | B6 | NAc | B6 | NA | |

| 3 | B6 | B6 | B6 | B6 | |

| 4 | PD-1−/− | B6.PD-1−/− | B6 | B6 | |

| 5 | Treg depletedd | B6.FoxP3-GFP | B6 | B6 | |

| 4b and 5b | 1 (control) | B6 and PD-1−/− | B6, B6.FoxP3-GFP, and B6.PD-1−/− | B6 and PD-1−/− | B6 and B6.PD-1−/− |

| 2 | B6 | B6 | B6 | B6 | |

| 3 | PD-1−/− | B6.PD-1−/− | PD-1−/− | B6.PD-1−/− | |

| 4 | B6 | B6 | PD-1−/− | B6.PD-1−/− | |

| 5 | Treg depleted | B6.FoxP3-GFP | PD-1−/− | B6.PD-1−/− |

The control group pooled data from uninfected B6.TCRα−/− recipients reconstituted with various cell subsets. To depict the uninfected control, the data from all groups of uninfected mice receiving the different transfers of experimental cell populations were pooled as an uninfected control for simplicity.

NA, infected intact wt B6 mice without any reconstitution.

Treg depleted, CD4 T cells lacking Treg cells.

Flow cytometry and IFN-γ production.

Surface staining was performed as described previously (39, 40). Spleen cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-, phycoerythrin (PE)-, or allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated antibodies, and the resulting direct immunofluorescence was analyzed by a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Bioscience) with Cellquest software (BD Bioscience) to detect the expression of murine CD4 (H129.19), CD8α (53-6.7), PD-1 (J43), or FoxP3 (FJK-16S) (BD Pharmingen or eBioscience). Intracellular/cytoplasmic staining (ICCS) of FoxP3 was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Briefly, extracellular staining with FITC anti-CD4 was performed, followed by fixation/permeabilization overnight and then intracellular staining with APC anti-FoxP3. ICCS of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD Bioscience). Briefly, splenocytes obtained at days 10 and 20 p.i. were restimulated with irradiated MAIDS-associated B6-1710 tumor cells in vitro overnight. These effectors were incubated with 10 μg/ml brefeldin A for 4 h prior to extracellular staining with FITC anti-CD44 (BD Bioscience) and peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP) anti-CD8 (Biolegend). The cells were then fixed in a 1% solution of paraformaldehyde and rendered permeable with buffer containing 0.5% saponin (Sigma). After permeabilization, the cells were cytoplasmically stained with APC anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2; eBioscience). Appropriate FITC-, PE-, or APC-conjugated Ig isotypes with irrelevant specificity were used as negative controls. All samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer using CellQuest software (BD Bioscience).

B6-cross-reactive anti-MAIDS/tumor-specific CTL generation and cytolytic assay.

Cytolytic assays were employed as previously described (11, 24). Briefly, splenocytes were isolated from various experimental mouse groups at days 10 and 20 p.i. and restimulated in vitro with irradiated MAIDS-associated B6-1710 tumor cells for 6 days. Cytolytic activity was measured by a standard 51Cr release assay using B6-1710 tumor cells as target cells.

Standard MAIDS readouts.

The following established standard readouts of MAIDS have been generally accepted to determine the extent of disease susceptibility and progression (18–23, 36, 39, 40, 46–48): (i) spleen size, with enlargement (measured by weight) of the spleen postinfection indicating MAIDS-associated B- and T-cell lymphoproliferation; (ii) serum IgG2a and IgM levels, with increased serum Ig levels representing MAIDS-associated polyclonal B-cell activation; and (iii) immunodeficiency, as evidenced by severely reduced splenic B-cell responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 μg/ml) stimulation and T-cell responses to concanavalin A (ConA) (2 μg/ml) stimulation (as measured by 3H-thymidine [TdR] incorporation) (23, 39, 40). Because all these disease readouts were found to be directly correlated with each other, for most of the data shown here, changes in spleen weight and immunodeficiency status are presented as representative disease readouts to demonstrate the development of LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis.

RNA isolation and viral load determinations.

The viral loads were determined for the BM5def and BM5eco components of the LP-BM5 retrovirus, as previously described (6). Briefly, total RNA was isolated from spleen tissue using Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and treated with a DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Following reverse transcriptase amplification of cDNA (Bio-Rad iScript cDNA Synthesis kit), real-time qRT-PCR was performed using iQ SYBR green Supermix and iCycler software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Infectious-center assay.

In vitro infectious-center assays, adopted from a variation of the standard XC cell plaque assay, were employed as previously described (24, 53). Briefly, seeded SC-1 cells were infected by coculture with a series of diluted splenocytes from infected experimental (versus uninfected control) mice at various days p.i. and incubated for 5 days. Infectious centers were quantified after irradiation of the SC-1 monolayer with UV light and overlaid with XC cells to develop plaques by 2% methylene blue staining.

Statistics.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple-group comparisons using SPSS software. To control for type I error due to multiple tests, the Bonferroni correction was applied, with a P value of <0.05 defined as significance, unless otherwise indicated. All error bars represent standard deviations (SD).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

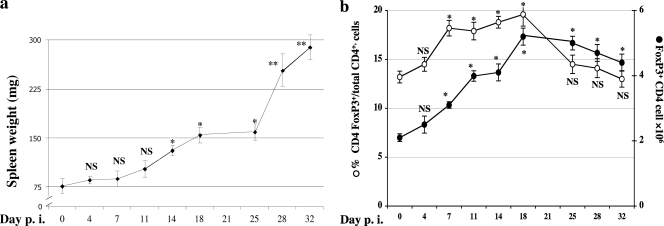

Expansion of FoxP3+ Treg cells during the development of MAIDS post-LP-BM5 infection.

Although we and others have noted the kinetics of development of the overt disease parameters of LP-BM5-induced MAIDS, the timing of the commitment to disease postinfection is largely unstudied beyond our findings that the interaction of CD4 T-cell CD154 with B-cell CD40 is required for both the initiation and early (first 3 to 4 weeks) progression of pathogenesis (20–22). As a first approach toward understanding a possible role of FoxP3+ CD4 Treg cells in MAIDS, we more closely followed the kinetics of expansion of this regulatory-cell subset versus that of LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis. Thus, the spleen weights of infected wt B6 mice significantly increased by 2 weeks p.i. compared to those of the uninfected controls and became increasingly elevated thereafter (Fig. 1 a); the apparent lag and then the especially steep increase around day 25 p.i. (Fig. 1a), however, was not a consistent finding in two repeat experiments. Second, in the context of this development of MAIDS in B6 mice (days 4 to 32 p.i.), we detected by flow cytometric analysis, via ICCS, an infection-induced expansion of FoxP3+ CD4 Treg cells (Fig. 1b). The mean number of total FoxP3+ CD4 Treg cells per spleen increased about 50% as early as 1 week p.i. (to 3 × 106 per spleen) compared to that of uninfected mice (∼2 × 106 per spleen at day 0). This expansion of CD4 Treg cells continued and peaked by day 18 p.i. Correspondingly, the percentage of FoxP3+ CD4 T cells among total CD4 splenocytes increased from 13.2% (at day 0) to 19.6% by day 18 p.i. (Fig. 1b). We observed similar patterns of CD4 Treg cell expansion in repeat experiments, including those utilizing FoxP3-GFP mice, in which FoxP3 Treg cells were identified by GFP fluorescence (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

(a) Kinetics of LP-BM5 retrovirus-induced pathogenesis in MAIDS-susceptible B6 mice. B6 mice were infected with LP-BM5 retrovirus. Disease was assessed in infected mice at the indicated days p.i. using standard MAIDS readouts. Changes in spleen weight, one representative activational parameter, are shown, with all the other disease readouts in agreement. Each treated group was compared to the uninfected control group. Three mice were used per group. NS (not significant), P ≥ 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. The data are representative of a total of three experiments, which showed a similar pattern of results. The error bars indicate SD. (b) Expansion of FoxP3+ Treg cells after LP-BM5 infection. B6 mice were infected with LP-BM5 retrovirus. FoxP3 intracellular staining (ICCS) of the splenocytes was performed at the indicated days p.i. The open ovals represent the percentages of FoxP3+ CD4 Treg cells among total CD4 T cells, and the solid ovals represent the total numbers of FoxP3+ CD4 Treg cells per spleen. Three mice were used per group. NS, P ≥ 0.05, and *, P < 0.05. The data are representative of a total of three experiments in B6 mice via ICCS determinations. Using FoxP3-GFP mice, in which flow cytometric detection of GFP expression was used to identify the Treg cells, resulted in a very similar pattern of results (data not shown).

B6.FoxP3-GFP mice are MAIDS susceptible.

Given this observed LP-BM5 infection-dependent rise in CD4 Treg cells, we wished to pursue their possible involvement in regulating MAIDS by manipulation of the CD4 Treg compartment. Our approach was to take advantage of FoxP3-GFP mice, which, though otherwise normal, contain the FoxP3 knock-in FoxP3-GFP allele, allowing the depletion of FoxP3-GFP-expressing Treg cells. First, it was important to determine the MAIDS susceptibility of B6.FoxP3-GFP mice compared to wt B6 mice, and thus, B6.FoxP3-GFP mice were infected with LP-BM5 and the development of MAIDS pathogenesis was assessed. Our results, after examining all disease parameters at 12 weeks p.i. (data not shown), indicate that B6.FoxP3-GFP mice developed full-blown MAIDS similar to that of prototypic MAIDS-susceptible B6 mice, as evidenced by all parameters of our standard panel of MAIDS readouts (see Materials and Methods). The data confirmed that the FoxP3-GFP allele does not result in any functional defects in the LP-BM5-induced pathogenic CD4 Th cell compartment relative to its ability to mediate LP-BM5-induced MAIDS and that the B6.FoxP3-GFP mice are thus suitable as donors of Treg-depleted CD4 Th cell preparations for further mechanistic analyses (see Fig. 3).

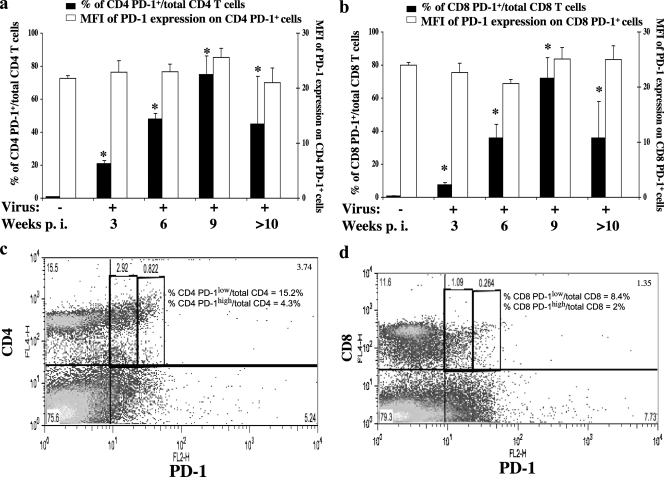

Upregulation of PD-1 expression as a result of LP-BM5 retroviral infection.

To consider manipulation of PD-1 expression as an approach to prevention of MAIDS, it was important to first extend the assessment of LP-BM5 infection-dependent upregulation of PD-1 to the protein level. Thus, flow cytometric analyses of spleen cells from LP-BM5-infected B6 mice at up to 12 weeks p.i. were performed to evaluate the relative cell surface expression of PD-1 on CD4 (and CD8) T cells over time following infection. The percentage of CD4 PD-1+ cells increased significantly as early as 1 week p.i. (data not shown), continued to increase until 9 weeks p.i., and then declined (Fig. 2 a, solid bars). In parallel, we observed a trend toward increased numbers of CD8 PD-1+ cells during the first 2 weeks of infection (data not shown), and by 3 weeks p.i., there was a significant increase in the percentages of CD8 PD-1+ cells, which continued up to 9 weeks p.i. and then declined (Fig. 2b, solid bars). In contrast, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1 on both CD4 (Fig. 2a, open bars) and CD8 (Fig. 2b, open bars) T cells remained about the same as for uninfected control mice, indicating no greater density of PD-1 expression per cell. By representative dot plot analyses, the expression of PD-1 could be subdivided into “high” versus “low” levels, based on MFI, for both CD4 and CD8 T cells (Fig. 2c and d), although even those labeled here as high seemed relatively modest compared to the very high levels described in the literature for other viral systems in which T cells were becoming exhausted (66). However, the increased percentages of CD4 and CD8 T cells expressing PD-1 were in keeping with a possible role for PD-1 in LP-BM5 viral pathogenesis and/or the host response to infection.

Fig. 2.

Upregulation of PD-1 on CD4 and CD8 T cells post-LP-BM5 infection. B6 mice were infected with LP-BM5 retrovirus. Splenocytes from 0 (uninfected), 3, 6, and 9 weeks p.i. and pooled splenocytes from >10 weeks p.i. were stained with anti-PD-1 and either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MAbs. Statistical analyses of the percentages (solid bars) of CD4 PD-1+ (a) or CD8 PD-1+ (b) cells expressing PD-1 were performed between the indicated groups and the uninfected group (week 0). *, P < 0.05. The error bars indicate SD. The comparisons of PD-1 MFI (open bars) of either CD4 PD-1+ (a) or CD8 PD-1+ (b) cells were not significant between any groups. Representative dot plots of the CD4 (c) and CD8 (d) T cells expressing PD-1 are shown, with a subdivision of the PD-1-positive cells into PD-1high versus PD-1low expression, based on MFI, at 3 weeks p.i.

A trend of enhanced LP-BM5-induced disease is observed following selective interruption of PD-1 expression by pathogenic CD4 T cells.

As an extension of our observation of exaggerated retroviral pathogenesis in LP-BM5-infected B6.PD-1−/− compared to wt B6 mice (23), we have been interested in determining the functional significance of PD-1 expression for the cell types required for LP-BM5 induction of MAIDS (i.e., CD4 T versus B cells). Such exaggerated disease appears to be due to a release from the normal negative control by PD-1/PD-L1 in wt B6 mice at the level of the critical pathogenic CD4 Th effector cell/B-cell interaction, which is mediated by CD154 ligation of CD40 (20–23).

Here, we further examined the functional significance of PD-1 expression on CD4 T cells and the presence of Treg cells within the CD4 T-cell compartment via a series of adoptive-transfer experiments (Table 1). As we previously reported (39), the approach used recipient B6 mice without T cells (B6.TCRα−/− mice) and thus unable to develop LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis without reconstitution with CD4 T cells (Fig. 3 a). Comparing wt versus PD-1−/− sources of the requisite CD4 T cells for LP-BM5 pathogenesis, first, there was no significant difference between the adoptive-transfer groups in which the origin of the CD4 T cells was wt versus PD-1−/− mice (Fig. 3a). However, there was a trend of PD-1−/− CD4 T cells mediating somewhat more pronounced viral pathogenesis (Fig. 3a). This trend was observed in all 3 experiments of this type. Thus, PD-1 expression on CD4 T (effector) cells may have the ability to limit LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis in infected wt B6 mice.

Second, we also studied the effect of depletion of Treg cells from the CD4 compartment (Table 1). Depletion appeared complete, and FoxP3-GFP+ CD4 Treg cells began to reappear substantially only by day 20 p.i., when their percentage relative to all CD4 T cells was about 1/3 of predepletion levels (data not shown). Whether this reappearance of Treg cells represents the induction of or conversion to induced Treg cells and/or the expansion of very small, undetectable numbers of persisting nTreg cells is unclear. However, most importantly, a 2- to 3-week p.i. period was created in which Treg cells were absent or in very low numbers to potentially allow a CD8 T-cell response to more easily occur. Mice reconstituted with CD4 T cells lacking CD4 Treg cells did not, upon infection, develop statistically significantly less disease (Table 1 and Fig. 3a, group 5).

Manipulation of Treg cells and simultaneous abrogation of the PD-1 pathway result in substantially less LP-BM5-induced pathogenesis.

The elevated expression of PD-1 (and consequently, its potential for negative signaling after engagement by PD-L) by pathogenic CD4 T cells may therefore account in part for our previous observation of less severe disease in wt B6 mice than in B6.PD-1−/− mice (23). However, significant increases in PD-1 expression post-LP-BM5 infection were observed, not only for CD4 T cells (Fig. 2a), but also for CD8 T cells (Fig. 2b). Elevated PD-1 expression by CD8 T cells may limit the induction and/or expansion of a protective CD8 CTL response in infected wt mice, thus contributing substantially to the susceptibility of wt B6 mice to LP-BM5 retroviral pathogenesis. To test this possibility, we included additional adoptive-transfer groups in these same experiments using B6.TCRα−/− recipients via reconstitution with CD8 T cells from either wt B6 (Fig. 3a) or B6.PD-1−/− (Fig. 3b) donors. In short, we next directly compared adoptive transfer of naïve wt CD8 T cells versus PD-1−/− CD8 T cells in the context of wt versus PD-1−/− versus FoxP3+ Treg cell-depleted, naïve CD4 T cells.

First, adoptive transfer of naïve wt CD8 T cells into T-cell-deficient (TCRα−/−) recipients did not mediate LP-BM5-mediated pathogenesis, nor, when combined with naïve wt CD4 T cells, was more pathogenesis observed than in adoptive transfer of wt CD4 T cells alone (21; W. Li, K. Green, and W. R. Green, unpublished data). Second, by comparison of adoptive transfer of various additional combinations of CD4 and CD8 T cells into TCRα−/− recipients, we found a significant reduction of spleen weight, as a representative measure of MAIDS, by selective blockade of the PD-1 negative-signaling pathway in the CD8 T-cell compartment (Fig. 3b, group 4 from left). This was most clearly observed when wt CD4 T cells were held constant and wt versus PD-1−/− CD8 T cells were compared (Fig. 3b, group 2 versus group 4; P = 0.032). Third, when PD-1 was eliminated from both the transferred CD4 and CD8 T-cell compartments, a significant change in retroviral pathogenesis was not observed (Fig. 3b, group 3). Our interpretation of this result is that the protective effect of removing PD-1 expression from the CD8 T-cell compartment is counterbalanced by the simultaneous removal of the PD-1 “brake” from the pathogenic CD4 Th compartment. Also, as discussed above, there was indeed a trend (though not statistically significant) toward more LP-BM5-mediated pathogenesis when PD-1−/− CD4 T cells were used with wt CD8 T cells (Fig. 3a).

Fourth, and most importantly, we observed a significant further reduction of MAIDS when both the Treg- and PD-1-mediated suppressive pathways were simultaneously blocked (Fig. 3b, group 5). Because Treg cell depletion and PD-1 pathway blockade target different immunosuppressive mechanisms, the combined strategy that interrupts both negative pathways further significantly (P = 0.012) reduced MAIDS pathogenesis (Fig. 3b, group 5) compared to the individual blockade of PD-1 on the CD8 T-cell population alone by use of a B6.PD-1−/− donor of these cells (Fig. 3b, group 4). Strikingly, this dual therapy resulted in essentially no LP-BM5-induced splenomegaly, with a level that was not statistically different from that in uninfected mice (Fig. 3b). This result was consistent in a total of three experiments. This pattern of results, including the most dramatic reduction of LP-BM5 pathogenesis observed following the combined interruption of negative regulation by CD4 Treg cells and the PD-1/PD-L pathway for CD8 T cells, was confirmed by the other parameters of our standard panel for MAIDS, including the immunodeficiency parameter, mitogen responsiveness (Fig. 3c and d).

Of special note, since the combined treatment relieves normal regulation by two fundamental control mechanisms, we carefully examined the spleen, kidneys, and skin from these combined-treatment mice and found no evidence of infiltrating lymphocytes or any other signs of autoimmune disease (data not shown).

Reduced induction of viral pathogenesis in the combined-treatment group compared to the overall viral load and numbers of virus-producing cells early postinfection.

Our results thus show that the combined treatment of CD4 Treg cell depletion and interruption of the PD-1 negative regulatory pathway in CD8 T cells may provide the basis for a synergistic immunotherapeutic approach to control LP-BM5 retrovirus-induced MAIDS. It was important to assess whether such reduced pathogenesis was correlated with an effect on the overall viral load. Thus, the expression of the pathogenic BM5def and helper BM5eco viruses was determined by qRT-PCR assays (6) for the experimental conditions depicted in Fig. 3 upon termination of the experiment at 10 weeks p.i. First, compared to the undetectable level of expression of the uninfected controls, all infected mouse groups demonstrated substantial expression of BM5def and BM5eco (Fig. 4 a and b). Second, among the various infected treatment groups, there were no significant differences in the terminal viral load for either the BM5def or BM5eco viral constituent of LP-BM5, and this viral expression was similar to that observed for infected control wt B6 mice (Fig. 4a, group 2). Thus, the decreased retroviral pathogenesis observed, particularly in the combined-treatment group, was not correlated with an overall reduced ability of LP-BM5 to infect and spread by the time p.i. of overt disease, including profound immunodeficiency.

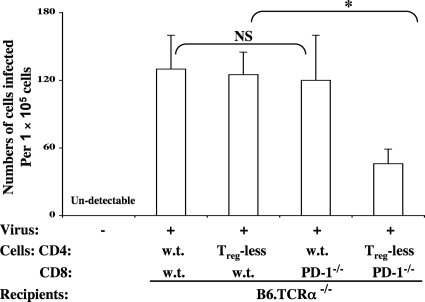

However, because qRT-PCR does not provide information on infectious virus, we also performed infectious-center assays at earlier time points, consistent with the up to 3-week period of commitment to full-blown disease, e.g., at days 10 and 20 p.i. The results showed that there may be a trend (but a statistically insignificant one) toward lower numbers of virus-producing cells at day 10 p.i. (data not shown). However, at day 20 p.i., there was a substantial reduction in the numbers of LP-BM5 virus-producing infectious centers that had clear significance for only the combined manipulation of CD4 Treg cell depletion and the use of PD-1−/− CD8 T cells (Fig. 5), as confirmed in two independent experiments. These results suggest that the reduction in LP-BM5 pathogenesis observed after combined treatment might be due to this decrease in infectious virus production at this apparently critical time in the pathogenic process.

Fig. 5.

CD4 Treg cell depletion and PD-1 blockade in CD8 T cells correlate with a decrease in LP-BM5 infectious centers. Infectious-center assays were performed at day 20 p.i. Infectious centers were quantified and determined as described in Materials and Methods. Statistical analyses were performed between infected groups: NS, P ≥ 0.05, and *, P < 0.05. Shown are representative data from two independent experiments with similar patterns of results.

Depletion of CD4 Treg cells and simultaneous abrogation of the PD-1 pathway in CD8 T cells results in priming for a cross-reactive MAIDS CTL response early p.i.

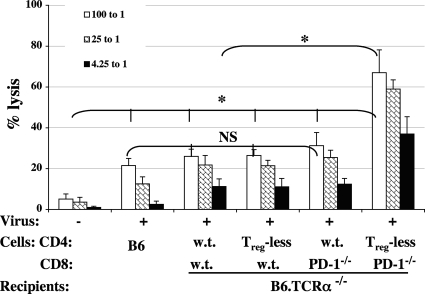

Given the observation of significantly reduced numbers of infectious centers at the early/intermediate time point of 20 days p.i. and our experimental approach to encourage a CD8 T-cell response, in part by employing CD8 T cells from PD-1−/− donor mice, we looked for evidence of a CD8 CTL response at various time points p.i. We focused particularly on the combinations of reconstituted T cells (Fig. 3) that utilized PD-1−/− CD8 T cells, i.e., those that provided reduced LP-BM5 retroviral pathogenesis, versus appropriate combinations that did not lead to reduced pathogenesis. Consistent with the results in Fig. 5 showing that the number of cells producing LP-BM5 retrovirus was significantly reduced at day 20 p.i., by this same time point p.i., LP-BM5 infection had primed for a substantial lytic response (Fig. 6). For both infectious centers (Fig. 5) and cytolytic activity (Fig. 6), the effects were statistically different from the other transfer combinations only following the simultaneous manipulation of initial removal of CD4 Treg cells and interruption of the PD-1/PD-L negative regulatory pathway in CD8 T cells. The specificity of these CTLs appeared to be against the cross-reactive determinants found on LP-BM5-infected spleen cells and LP-BM5-induced tumor cells, which we have previously defined and studied in some detail (11, 24, 25). Along these lines, here, only after LP-BM5 infection did sufficient priming occur in vivo for a subsequent in vitro response to LP-BM5-induced MAIDS tumor cell restimulation to yield substantial lytic activity (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Depletion of CD4 Treg cells and simultaneous abrogation of the PD-1 pathway in CD8 T cells resulted in significantly enhanced CTL response. Splenocytes were isolated from mice at day 20 p.i. and cultured with irradiated MAIDS-associated B6-1710 tumor cells in vitro for 6 days, and the anti-MAIDS-associated tumor-specific cytolytic activities were measured against B6-1710 tumor target cells as detailed in Materials and Methods. Statistical analyses, based on the 100:1 effector-to-target-cell (E/T) ratio, were performed between infected groups or compared to uninfected control mice: NS, P ≥ 0.05, and *, P < 0.05. The lytic data shown here are representative of two independent experiments with similar patterns of results. The error bars indicate SD.

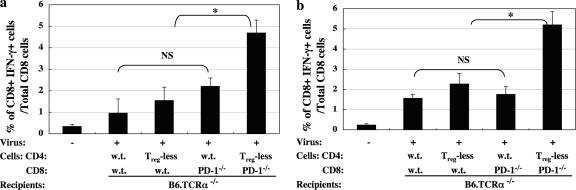

We also examined several more general correlates of CD8 T-cell activation/function, including CD107a, granzyme B, and IFN-γ expression. In terms of further characterization of the CD8 CTL response beyond the described lytic activity, the results were most informative for IFN-γ expression as assessed by ICCS. Thus, a statistically significant increase in infection-dependent IFN-γ production by CD8 T cells was reached at days 10 and 20 p.i., with, again, the dual-treatment group of CD4 Treg cell depletion and elimination of PD-1 expression on the CD8 T cells leading to the most dramatic response, and different from the cell transfers involving either wild-type cells or the two single-treatment approaches (Fig. 7 a and b).

Fig. 7.

Depletion of CD4 Treg cells and simultaneous abrogation of the PD-1 pathway in CD8 T cells resulted in significantly enhanced IFN-γ production. Splenocytes were isolated from mice at days 10 (a) and 20 (b) p.i. and cultured with irradiated MAIDS-associated B6-1710 tumor cells in vitro overnight. The percentage of CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ was determined following measurement by ICCS, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Statistical analyses were performed between all infected groups as depicted (NS, P ≥ 0.05, and *, P < 0.05) or compared to uninfected control mice, with all four experimental groups on the right significantly different (P < 0.05) from the uninfected control group on the far left. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments with similar patterns of results.

Implications of the present study and concluding remarks.

In this study, we demonstrated that CD4 Treg cell depletion and/or selective interruption of the PD-1/PD-L1 negative signaling pathway, specifically in the CD8 T-cell compartment, leads to a reduction in LP-BM5-induced retroviral pathogenesis. We have previously reported that, although B6 mice are unable to generate protective anti-LP-BM5 gag CD8 CTLs, as do resistant mouse strains (44, 45, 58), uninfected B6 mice can respond to a MAIDS-associated cross-reactive determinant(s) present on both end stage MAIDS B6 lymphomas and “normal” LP-BM5-infected cells (11, 24, 25). We have shown that by adoptive transfer these “anti-MAIDS” CTLs can be protective (25). Therefore, it seems likely that when susceptible B6 mice are infected with LP-BM5, CD8 (precursor) CTLs, though initially present and functional, subsequently fail to expand and/or to function sufficiently to control either the initiation of MAIDS or disease progression at early and/or later stages of infection. This lack of an effective CD8 CTL response might be initially due to suppression from the expanded FoxP3+ CD4 Treg cell population (Fig. 1b) and/or the upregulation of PD-1 on activated anti-MAIDS CD8 T cells (Fig. 2b and d) and, subsequently, CD8 T-cell functional inhibition. The relevant CD8 CTL response may thus not be of sufficient strength early on and/or of sufficient duration to inhibit MAIDS prior to the onset of the profound immunodeficiency induced by LP-BM5 infection.

In this paper, we demonstrated the substantial potential to amplify this weak anti-MAIDS CD8 T-cell response in MAIDS-susceptible B6 mice through Treg cell removal and/or selective interruption of the PD-1 negative signaling pathway. Indeed, we show that a significant reduction of LP-BM5 pathogenesis occurred following selective blockade of the PD-1 negative signaling pathway in the CD8 T-cell compartment (Fig. 3b and d, group 4). Moreover, there was a further significant reduction of pathogenesis when both Treg and CD8 T-cell PD-1/PD-L-mediated suppressive pathways were blocked (Fig. 3b and d, group 5), indicating that the combined treatment leads to novel synergistic effects that dramatically inhibit LP-BM5-induced disease.

The main cellular mechanism responsible for this reduction in retroviral pathogenesis may well be an amplification of the CD8 T-cell response to the cross-reactive epitope(s) present on cells of LP-BM5 virus-infected mice, as we have previously described (11, 24, 25) and discussed above. Only in the case of the combined manipulation of CD4 Treg cell depletion and use of PD-1−/− CD8 T cells does robust priming for this “anti-MAIDS” CTL response occur by day 20 p.i. (Fig. 6), a time close to that by which significantly increased PD-1 expression is first evident in the CD8 T-cell compartment (Fig. 2b and d) and the peak expansion of Treg cells occurs p.i. (Fig. 1b). This in vivo-primed CD8 CTL population also expresses IFN-γ upon restimulation with MAIDS tumor cells (Fig. 7), but whether this also contributes to the observed protection from MAIDS is unclear. However, in MAIDS-resistant BALB/c background mice we have shown that the anti-LP-BM5 retroviral gag CD8 CTLs that are protective rely only on (perforin-mediated) cytolysis, not IFN-γ production, to mediate their in vivo protective effects (54).

Particularly if CD8 T-cell lytic effector function is the only or the predominant mechanism of protection in B6 mice, a further question is why both CD4 Treg cell depletion and the removal of PD-1 from the CD8 T cells are required for this lytic response. However, it cannot be assumed that there is normally mechanistic linkage between the inhibitory effects of CD4 Treg cells and CD8 T-cell-expressed PD-1-induced negative regulation. Rather, many independent effects are possible that would lead to the observed synergistic effects of the combined treatment. For example, as a normally weak (at best) and/or transient CD8 CTL response, this B6 response may be dependent on CD4 T-cell help (by nonpathogenic Th1 cells). The inhibitory CD4 Treg cells may target these helper CD4 T cells, rather than directly targeting the CD8 CTLs, as is obviously the case when PD-1−/− mice are the donors of the CD8 T-cell compartment.

The in vivo targets for the cross-reactive CD8 CTLs here may well be LP-BM5 virus-producing cells, as there is a concomitant statistically significant decline at day 20 p.i. in retroviral infectious centers, again only after the combined-treatment approach (Fig. 5). However, the total overall viral load by qRT-PCR assays for both the BM5def and BM5eco components of LP-BM5, when assessed at the termination of the experiment at 10 weeks p.i., was not significantly different between the variously treated groups (Fig. 4). Thus, it may be that a high effective retroviral titer may be required around day 20 p.i. for a critical target cell type that is essential for the progression of viral pathogenesis to become infected. This apparent disconnect between the endpoint viral load and early infectious virus production is not entirely unexpected. LP-BM5 infects and is expressed by many different cell types. We have studied several B6 knockout and transgenic mice, or mice treated with blocking anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody (MAb) in vivo, to reduce/eliminate viral pathogenesis without significant effects on the terminal viral load, including that measured by qRT-PCR (18–22). Thus, in this ecotropic retroviral system, several cell types should become infected, some perhaps irrelevant to the initiation and progression of pathogenesis (particularly if infected weeks after LP-BM5 injection and commitment to disease), resulting in a “nonlinear” correlation between the terminal viral load and the extent of disease. Nonetheless, a further unexpected result was our observation that while the single approach of removal of PD-1 expression from CD8 T cells leads to somewhat less retroviral pathogenesis (Fig. 3b and d), a partial reduction in viral titers was not observed, whether assessed at the terminal time point, as discussed above (Fig. 4), or at day 10 or 20 p.i. by infectious-center analysis (Fig. 5). One possible explanation is that removal of PD-1 from the “anti-MAIDS” CD8 CTLs may primarily affect their longevity and thus the duration of the response, which may be a crucial aspect of protection from (cumulative) viral pathogenic events, whereas both viral load/production assays and in vitro assessment of CD8 T-cell lytic activity are only point-in-time measurements that would not necessarily reflect a crucial duration of CTL action in vivo.

Currently, we are in the process of further examining the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of the synergistic protective effects on retroviral pathogenesis that we have observed following blockade of these two distinct regulatory pathways. Our results may provide insight into strategies to enhance CD8 T-cell-mediated antiviral immunity, not only for LP-BM5-induced MAIDS, but also, more broadly, for immunotherapeutic approaches involving the manipulation of a negative regulatory pathway(s) to treat other retrovirus-induced immunodeficiencies and other viral diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA50157 (to W.R.G.), by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 81060252), and by a Hitchcock Foundation Award (to W.L.). W. L. was funded in part by a fellowship from NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases T32 training grant AI07363. Flow cytometry was performed at Dartmouth Medical School in the Dartlab Flow Cytometry and Immune Monitoring Laboratory, which was established by equipment grants from the Fannie E. Rippel Foundation, the NIH Shared Instrument Program, and Dartmouth Medical School and which is supported in part by a Core Grant (CA 23108) from the National Cancer Institute to the Norris Cotton Cancer Center and an NIH/NCRR COBRE P20 grant (RR16437) on Molecular, Cellular, and Translational Immunological Research (W.R.G., principal investigator).

We thank Kathy A. Green, Ling Cao, Cynthia A Stevens, and Megan A. O'Connor for critically reading the manuscript and for their technical support and helpful discussions.

We have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 September 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aandahl E. M., Michaelsson J., Moretto W. J., Hecht F. M., Nixon D. F. 2004. Human CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells control T-cell responses to human immunodeficiency virus and cytomegalovirus antigens. J. Virol. 78:2454–2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agata Y., et al. 1996. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 8:765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aziz D. C., Hanna Z., Jolicoeur P. 1989. Severe immunodeficiency disease induced by a defective murine leukaemia virus. Nature 338:505–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barber D. L., et al. 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439:682–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beilharz M. W., et al. 2004. Timed ablation of regulatory CD4+ T cells can prevent murine AIDS progression. J. Immunol. 172:4917–4925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cook W. J., Green K. A., Obar J. J., Green W. R. 2003. Quantitative analysis of LP-BM5 murine leukemia retrovirus RNA using real-time RT-PCR. J. Virol. Methods 108:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Day C. L., et al. 2006. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 443:350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dietze K. K., et al. 2011. Transient depletion of regulatory T cells in transgenic mice reactivates virus-specific CD8+ T cells and reduces chronic retroviral set points. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2420–2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dittmer U., et al. 2004. Functional impairment of CD8(+) T cells by regulatory T cells during persistent retroviral infection. Immunity 20:293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elrefaei M., Baker C. A., Jones N. G., Bangsberg D. R., Cao H. 2008. Presence of suppressor HIV-specific CD8+ T cells is associated with increased PD-1 expression on effector CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 180:7757–7763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Erbe J. G., Green K. A., Crassi K. M., Morse H. C., III, Green W. R. 1992. Cytolytic T lymphocytes specific for tumors and infected cells from mice with a retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Virol. 66:3251–3256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fontenot J. D., Rasmussen J. P., Gavin M. A., Rudensky A. Y. 2005. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 6:1142–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fontenot J. D., et al. 2005. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity 22:329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fontenot J. D., Rudensky A. Y. 2005. A well adapted regulatory contrivance: regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nat. Immunol. 6:331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fredrickson T. N., et al. 1985. Multiparameter analyses of spontaneous nonthymic lymphomas occurring in NFS/N mice congenic for ecotropic murine leukemia viruses. Am. J. Pathol. 121:349–360 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freeman G. J., Wherry E. J., Ahmed R., Sharpe A. H. 2006. Reinvigorating exhausted HIV-specific T cells via PD-1-PD-1 ligand blockade. J. Exp. Med. 203:2223–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaur A., Green W. R. 2003. Analysis of the helper virus in murine retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome: evidence for immunoselection of the dominant and subdominant CTL epitopes of the BM5 ecotropic virus. Viral Immunol. 16:203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Green K. A., Ahonen C. L., Cook W. J., Green W. R. 2004. CD40-associated TRAF 6 signaling is required for disease induction in a retrovirus-induced murine immunodeficiency. J. Virol. 78:6055–6060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Green K. A., Cook W. J., Sharpe A. H., Green W. R. 2002. The CD154/CD40 interaction required for retrovirus-induced murine immunodeficiency syndrome is not mediated by upregulation of the CD80/CD86 costimulatory molecules. J. Virol. 76:13106–13110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Green K. A., et al. 1996. Antibody to the ligand for CD40 (gp39) inhibits murine AIDS-associated splenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, and immunodeficiency in disease-susceptible C57BL/6 mice. J. Virol. 70:2569–2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green K. A., Noelle R. J., Durell B. G., Green W. R. 2001. Characterization of the CD154-positive and CD40-positive cellular subsets required for pathogenesis in retrovirus-induced murine immunodeficiency. J. Virol. 75:3581–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Green K. A., Noelle R. J., Green W. R. 1998. Evidence for a continued requirement for CD40/CD40 ligand (CD154) interactions in the progression of LP-BM5 retrovirus-induced murine AIDS. Virology 241:260–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Green K. A., Okazaki T., Honjo T., Cook W. J., Green W. R. 2008. The programmed death-1 and interleukin-10 pathways play a down-modulatory role in LP-BM5 retrovirus-induced murine immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Virol. 82:2456–2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Green W. R., Crassi K. M., Schwarz D. A., Green K. A. 1994. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed against MAIDS-associated tumors and cells from mice infected by the LP-BM5 MAIDS defective retrovirus. Virology 200:292–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Green W. R., Green K. A., Crassi K. M. 1994. Adoptive transfer of polyclonal and cloned cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) specific for mouse AIDS-associated tumors is effective in preserving CTL responses: a measure of protection against LP-BM5 retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency. J. Virol. 68:4679–4684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenwald R. J., Freeman G. J., Sharpe A. H. 2005. The B7 family revisited. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:515–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hasenkrug K. J., Dittmer U. 2010. Comment on “Premature terminal exhaustion of Friend virus-specific effector CD8+ T cells by rapid induction of multiple inhibitory receptors.” J. Immunol. 185:1349 (Author's reply, 185:1349–1350.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ho O., Green W. R. 2006. Cytolytic CD8+ T cells directed against a cryptic epitope derived from a retroviral alternative reading frame confer disease protection. J. Immunol. 176:2470–2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishida Y., Agata Y., Shibahara K., Honjo T. 1992. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 11:3887–3895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iwai Y., Terawaki S., Ikegawa M., Okazaki T., Honjo T. 2003. PD-1 inhibits antiviral immunity at the effector phase in the liver. J. Exp. Med. 198:39–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Iwashiro M., et al. 2001. Immunosuppression by CD4+ regulatory T cells induced by chronic retroviral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:9226–9230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jolicoeur P. 1991. Murine acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (MAIDS): an animal model to study the AIDS pathogenesis. FASEB J. 5:2398–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kinter A., et al. 2007. Suppression of HIV-specific T cell activity by lymph node CD25+ regulatory T cells from HIV-infected individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:3390–3395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kinter A. L., et al. 2007. CD25+ regulatory T cells isolated from HIV-infected individuals suppress the cytolytic and nonlytic antiviral activity of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in vitro. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 23:438–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klinken S. P., Fredrickson T. N., Hartley J. W., Yetter R. A., Morse H. C., III 1988. Evolution of B cell lineage lymphomas in mice with a retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome, MAIDS. J. Immunol. 140:1123–1131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klinman D. M., Morse H. C., III 1989. Characteristic of B cell proliferation and action in murine AIDS. J. Immunol. 142:1144–1149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Latarjet R., Duplan J. F. 1962. Experiments and discussion on leukamogenesis by cell-free extracts of radiation-induced leukemia in mice. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 5:339–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Latchman Y. E., et al. 2004. PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:10691–10696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li W., Green W. R. 2007. Murine AIDS requires CD154/CD40L expression by the CD4 T cells that mediate retrovirus-induced disease: is CD4 T cell receptor ligation needed? Virology 360:58–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li W., Green W. R. 2006. The role of CD4 T cells in the pathogenesis of murine AIDS. J. Virol. 80:5777–5789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li Y. N., et al. 2010. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress the immune responses of mouse embryo fibroblasts to murine cytomegalovirus infection. Immunol. Lett. 131:131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liang B., et al. 1996. Murine AIDS, a key to understanding retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency. Viral Immunol. 9:225–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. MacDonald A. J., et al. 2002. CD4 T helper type 1 and regulatory T cells induced against the same epitopes on the core protein in hepatitis C virus-infected persons. J. Infect. Dis. 185:720–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mayrand S. M., Healy P. A., Torbett B. E., Green W. R. 2000. Anti-Gag cytolytic T lymphocytes specific for an alternative translational reading frame-derived epitope and resistance versus susceptibility to retrovirus-induced murine AIDS in F(1) mice. Virology 272:438–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mayrand S. M., Schwarz D. A., Green W. R. 1998. An alternative translational reading frame encodes an immunodominant retroviral CTL determinant expressed by an immunodeficiency-causing retrovirus. J. Immunol. 160:39–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morse H. C., III, et al. 1992. Retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency in the mouse: MAIDS as a model for AIDS. AIDS 6:607–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mosier D. E., Yetter R. A., Morse H. C., III 1987. Functional T lymphocytes are required for a murine retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency disease (MAIDS). J. Exp. Med. 165:1737–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mosier D. E., Yetter R. A., Morse H. C., III 1985. Retroviral induction of acute lymphoproliferative disease and profound immunosuppression in adult C57BL/6 mice. J. Exp. Med. 161:766–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Okazaki T., Honjo T. 2006. The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 27:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Petrovas C., et al. 2006. PD-1 is a regulator of virus-specific CD8+ T cell survival in HIV infection. J. Exp. Med. 203:2281–2292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Piccirillo C. A., Shevach E. M. 2004. Naturally-occurring CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells: central players in the arena of peripheral tolerance. Semin. Immunol. 16:81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rouse B. T., Sarangi P. P., Suvas S. 2006. Regulatory T cells in virus infections. Immunol. Rev. 212:272–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rowe W. P., Pugh W. E., Hartley J. W. 1970. Plaque assay techniques for murine leukemia viruses. Virology 42:1136–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rutkowski M. R., Ho O., Green W. R. 2009. Defining the mechanism(s) of protection by cytolytic CD8 T cells against a cryptic epitope derived from a retroviral alternative reading frame. Virology 390:228–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rutkowski M. R., Stevens C. A., Green W. R. 2011. Impaired memory CD8 T cell responses against an immunodominant retroviral cryptic epitope. Virology 412:256–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sakaguchi S. 2004. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:531–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sakaguchi S., et al. 2001. Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 182:18–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schwarz D. A., Green W. R. 1994. CTL responses to the gag polyprotein encoded by the murine AIDS defective retrovirus are strain dependent. J. Immunol. 153:436–441 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shevach E. M. 2004. Regulatory/suppressor T cells in health and disease. Arthritis Rheum. 50:2721–2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Siliciano R. F., et al. 1988. Analysis of host-virus interactions in AIDS with anti-gp120 T cell clones: effect of HIV sequence variation and a mechanism for CD4+ cell depletion. Cell 54:561–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takamura S., et al. 2010. Premature terminal exhaustion of Friend virus-specific effector CD8+ T cells by rapid induction of multiple inhibitory receptors. J. Immunol. 184:4696–4707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Trautmann L., et al. 2006. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nat. Med. 12:1198–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vahlenkamp T. W., Tompkins M. B., Tompkins W. A. 2004. Feline immunodeficiency virus infection phenotypically and functionally activates immunosuppressive CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 172:4752–4761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Velu V., et al. 2009. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature 458:206–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weiss L., et al. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus-driven expansion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress HIV-specific CD4 T-cell responses in HIV-infected patients. Blood 104:3249–3256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wherry E. J., et al. 2007. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 27:670–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yetter R. A., et al. 1988. CD4+ T cells are required for development of a murine retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome (MAIDS). J. Exp. Med. 168:623–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zelinskyy G., et al. 2009. The regulatory T-cell response during acute retroviral infection is locally defined and controls the magnitude and duration of the virus-specific cytotoxic T-cell response. Blood 114:3199–3207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]