Abstract

Incarcerated women are among the most vulnerable and perhaps the least studied populations in the US. Significant proportions of female inmates are substance users, and many living in unstable housing conditions or being homeless. Female inmates are often at high risk of engaging in sex exchange for drugs or housing needs. While a disproportionate number of incarcerated women have experienced childhood household adversities and maltreatments, the effects of these childhood experiences on psychosocial and behavioral outcomes of this population in later life. We apply a life course perspective to examine these pathways in a sample of incarcerated women in Cook County, Illinois. Findings demonstrated lasting, but differential, effects of household adversities and childhood abuse on subsequent life risks and opportunities among these women.

Keywords: homelessness, sex-trade, structural equation model

Introduction

In recent years the number of incarcerations in the US has increased dramatically, from under 200,000 in 1970 to over 2 million in 2008 (Couture & Sabol, 2008). While the proportion of women in the incarcerated population is still small, at about 7%, the number of female inmates in state and federal correctional facilities (66.7%) has grown faster than the number of male incarcerations (42.8%) between 1995 and 2007 (Kruttschnitt, Gartner & Hussemann, 2008; West & Sabol, 2009). Incarcerated women are disproportionately affected by a myriad of health issues, such as substance abuse, HIV infection, and other sexually transmitted diseases (Hammett, Harmon, & Rhodes, 2002; National Commission on Correctional Health, 2002; Puisis, Levine, & Mertz, 1998). In fact, the HIV prevalence rate is higher among women compared to men in correctional settings (Harrison & Beck, 2005). In 2008, 1.9% of women compared with 1.5% of men in state and federal prisons were HIV positive (Maruschak, 2009); and 2.3% of female and 1.2% of male jail inmates had HIV in 2002 (Maruschak, 2006).

Women in jail

Female inmates are more likely than male inmates to be substance dependent or abusers (52% vs. 44%) (Harrison & Beck, 2005; Karberg & James, 2005; Mumola & Karberg, 2006). Specifically in Chicago, over 80% of women in a county jail reported a history of substance use (Chicago Coalition for the Homeless [CCH], 2002). A disproportionate number of incarcerated women engage in sex trade to meet their drug or survival needs. Raj and colleagues (2006) found that 31% of women incarcerated in the Rhode Island Department of Corrections had ever been arrested for sex trade. Similarly, over 40% of women in the Cook County Department of Corrections reported that they have engaged in prostitution (CCH, 2002). Women who engage in sex trade are also more likely to be homeless and to have a history of incarceration (Lehmann, Kass & Drake, 2007; Weiser et al., 2006). In fact, women often engage in prostitution for shelter, drugs, and other survival needs (CCH, 2002; Weiser et al., 2006).

Typically, incarcerated women are poor and unemployed (CCH, 2002; Greenfeld & Snell, 2000). Incarcerated individuals often live in unstable housing or are homeless (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2008). One survey conducted in Chicago found that over 50% of women in a local jail were living in unstable housing or were homeless prior to incarceration (James, 2004). A high rate of shelter use is also reported among ex-offenders released from correctional facilities (Metraux & Culhane, 2006; Travis, 2007). A study documented that 12% of persons released from New York State Prison experienced a shelter stay within two years following release (Kuno, Rothbard, Averyt & Culhane, 2000). Similarly, significant proportions of homeless individuals also spend time in jails and prisons (Booth, Sullivan, Koegel & Burnam, 2002; Folsom et al., 2005; Johnson & Young, 2002; Reback, Kamien & Amass, 2007).

Moreover, studies have found that a large proportion of incarcerated women have experienced childhood abuse (Browne, Miller & Maguin, 1999; Gilfus, 1992). According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 31.7% of women in state prisons have been physically or sexually abused before age of 18 (Snell, 1994). Interestingly, studies have also documented that women who engage in sex trade are more likely to have a history of childhood violence such as emotional, sexual, or physical abuse (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1996; Wyatt, Guthrie & Notgrass, 1992). Similarly, Covington and Kohen (1984) argue that women with substance abuse problems have higher rates of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse during childhood than non-abusers. Kendler and colleagues (2000) reported similar findings where as many as 62%–81% of adult women in drug treatment programs have been victimized by childhood abuse.

Clearly, these problems do not occur in isolation. Incarcerated women are exposed to multiple risks over their life course, and cumulative effects of these life events may shape pathways leading to adulthood life circumstances. Understanding the processes that link their various social and health outcomes requires a comprehensive framework which may help explain particular life trajectories leading to adulthood adversities.

Life course approach

Although the associations between childhood adverse experiences and adulthood outcomes have been well documented (Edwards, Halpern & Wechsberg, 2006; Finkelhor & Browne, 1985; Kendler et al., 2000; Putnam, 2003; Wechsberg et al., 2003), the specific mechanisms by which adverse childhood events influence outcomes in later life, are relatively unexplored (Kendall-Tackett, 2002; Springer, Sheridan, Kuo & Carnes, 2003). Particularly concerning incarcerated women, the life course approach may help better conceptualize disproportionate exposure to childhood risks and adulthood adverse outcomes in this population. The life course has been defined as "pathways through the age differentiated life span" (Elder, 1985), in which the course of life events over time shape particular life transitions and trajectories (Elder, 1985; Kawachi, Kennedy & Wilkinson, 1999; Settersten, 2003). The life course perspective examines the consequences of one’s life experiences as processes within life context (Bengtson & Allen, 1993). Early childhood factors such as experiencing abuse or witnessing violence set in motion particular life-course trajectories, and determine exposure to risks, including school failure, substance use, or delinquency (Bolger & Patterson, 2001; Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; Pulkkinen & Tremblay, 1992). The exposure to these risks may increase the likelihood of engaging in illicit activities during their adulthood, leading to an increased risk of incarceration (Hall, 2000; Horwitz, Widom, McLaughlin & White, 2001; Min, Farkas, Mommes & Singer, 2007; Widom & Kuhns, 1996).

Childhood adverse events may affect later-life outcomes, primarily by influencing education and the socioeconomic opportunities (Crimmins & Saito, 2001; Mirowsky & Hu, 1996; Ross & Wu, 1995). Children who experience childhood maltreatment are more likely to fail in school or even school dropout, which limits one’s life chances, thereby increasing risks for adverse outcomes during adulthood (Kinard, 1999; Miech & Hauser, 2001; Solomon & Serres, 1999). For example, studies have found that neglected children perform worse on academic tasks than non-neglected children (Kendall-Tackett & Eckenrode, 1996; Slade & Wissow, 2007). These studies further conclude that because of lower educational attainment, children with history of abuse are more likely than those without to have increased risk of school dropout and worse economic outcomes in adulthood (Fang & Tarui, 2009; Hall, 2000; Kendall-Tackett & Eckenrode, 1996; Macmillan, 2001). Widom and colleagues have documented that women who experienced childhood abuse have shown increased risk of engaging in risky sexual behaviors (Widom, 1989; Widom & Kuhns, 1996). Silbert (1981) reported that 78% of women reported starting prostitution as juveniles, and often had a history of childhood sexual abuse; and 77% of these women reported that the sexual abuse affected their decision to be involved in prostitution.

Childhood abuse may also influence later life by increasing risk of psychiatric disorder in young adults (Fergusson, Horwood & Lynskey, 1996). Silverman and others found that 80% of abused young adults had one or more psychiatric disorders. When compared to their non-abused counterparts, abused individuals showed higher rates of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, emotional-behavioral problems and suicide attempts (Silverman, Reinherz & Giaconia, 1996).

Parental involvement may also affect children’s school performance and behaviors (Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Goebert et al., 2004; Murray & Farrington, 2005). Studies have documented that parental participation in the educational processes and experiences of their children increased academic measures including grades, teacher rating scales, academic attitudes, and behaviors (Jeynes, 2007; Patall, Cooper & Robinson, 2008). Parents who have drug problems or who are incarcerated may not be involved in child’s school activities. For example, Dube and colleagues (2003) found that having a household member with mental illness or having an incarcerated household member increased the odds of initiating drug use by 1.9 times. Children of incarcerated parents are a highly vulnerable group with multiple risk factors for adverse outcomes. Studies suggest that the accumulative effect of these family risk factors may affect children’s adjustment (Hetherington, Bridges & Insabella, 1998; O'Conner, Dunn, Jenkins, Pickering & Rasbash, 2001; Stanton-Chapman, Chapman, Kaiser, & Hancock, 2004). Similarly, Murray and Farrington (2005) documented that having incarcerated parents increased the risk of child’s delinquency.

In summary, disadvantage accumulates over time through a series of life events among incarcerated women. The life course approach may help conceptualize ways in which this myriad of co-occurring socio-behavioral conditions, such as childhood abuse, adverse parental events, substance use, economic disadvantage, and risky sexual practices, are associated and differentiate their social and health related trajectories. In particular, these cumulative disadvantages may limit women’s life chances, contributing to negative social, economic, and behavioral outcomes (O'Rand, 1996).

Methods

Research question

The purpose of this study is to examine how undesirable childhood experiences affect current life conditions among incarcerated women. We modeled potential pathways between childhood experiences (parental characteristics and abuse experience) and adulthood outcomes (sex trade, homelessness, and incarceration), using structural equation models. Educational attainment and employment status were examined as mediators of the impact that childhood abuse adverse events has on adult homelessness, sex trade, and repeat incarceration. We hypothesize that children growing up in disadvantaged households may be more likely to be exposed to childhood sexual and/or physical abuse, and that these experiences affect individual abilities to accumulate social and human capital: education, employment, and social support networks. These disempowering life circumstances may in turn precipitate psychosocial, economic, and behavioral issues such as substance abuse, homelessness, prostitution, and incarceration.

Model

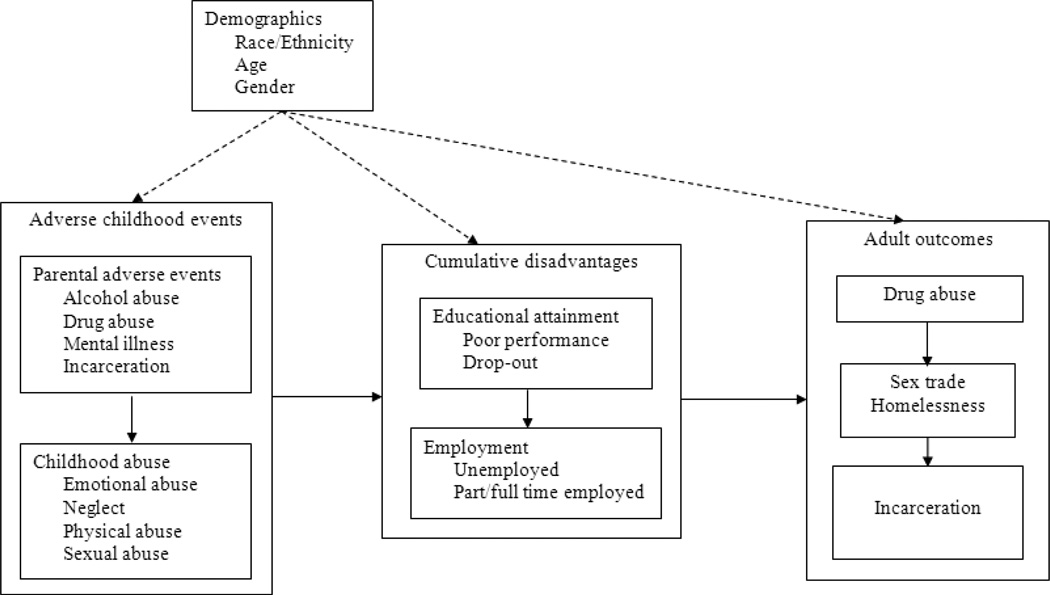

Figure 1 depicts a conceptual model explaining the relationships between childhood experiences, cumulative disadvantages, including lack of educational attainment, severity of drug abuse, and repeat incarceration, and adult outcomes, including employment status, homelessness, and involvement with sex trade among incarcerated women.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model

Utilizing the life course perspective, we hypothesize that parental adverse events such as parents’ alcohol abuse, drug abuse, mental health problems, and incarceration increase the risk of experiencing childhood abuse including neglect, emotional, physical, or sexual abuse. History of parental adverse events and childhood abuse would then negatively affect women’s educational attainment, which then would limit employment opportunities. Parental and childhood adverse experiences may also increase the risk and severity of drug abuse. We assume that the severity of drug use and educational attainment are correlated, although it may be difficult to determine the direction of this relationship.

We also predict that those who had a history of parental and childhood adverse events would be more likely to be incarcerated. Employment status is affected by the level of educational attainment. Women’s drug use behavior may also limit the probability of being employed. Finally, adulthood outcomes, homelessness and engaging in sex trade, would be directly and indirectly affected by childhood experience, cumulative disadvantage, and current employment status. In addition, race/ethnicity and age are expected to influence the life trajectories and outcomes, thus need to be controlled for.

Dataset

We utilized an existing survey data collected from 235 women detained in the women’s divisions in Cook County Jail, Chicago, IL. The protocol for the secondary analysis of these data was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Illinois at Chicago. The original survey was conducted in 2001 by the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless (CCH). The survey was based on a total of 235 women (21%) who were sampled from a population of 1,117 women housed in the women’s divisions in the Cook County Jail on October 31, 2001. Female inmates were invited to participate in the survey, and those who volunteered were randomly sampled to participate. Interviewers then called the number for the survey. Consent was obtained prior to the survey, informing participants concerning the voluntary nature of the study, providing assurances of confidentiality, and an acknowledgement that participation would not affect the disposition of their current charges. Trained volunteers and the CCH staff conducted the survey, which took 15–30 minutes (CCH, 2002).

Setting

The Cook County Jail is the largest single-site jail in the US. Between 1995 and 2004, there were over 875,000 incarcerations involving 389,532 individuals, with an average of over 97,000 incarcerations per year within this facility (unpublished preliminary study by the authors). Of those, 63% were African Americans, 17% were Hispanic, and 19% were non-Hispanic white. The proportion of women in the inmate population increased modestly from 14% in 1996 to 16% in 2004. On average, the jail makes over 16,000 female incarcerations per year.

Measures

We examined two adulthood outcome variables: current homelessness and involvement in sex trade. Current homelessness was a dichotomous variable indicating whether a woman was homeless during the 30 days before the index incarceration. Current engagement in sex trade, a dichotomous variable, indicated whether a woman had engaged in sex trade, such as street work, stripping, escort services, sex tours, trafficking, and survival sex, during the 30 days before the index incarceration.

Childhood adverse events were a set of dichotomous variables including: 1) having parent(s) who were alcohol abusers, 2) who were drug abusers, 3) who had mental health problems, 4) who had history of criminal justice involvement, 5) having been neglected, 6) been emotionally, 7) physically, and 8) sexually abused during childhood. Using these eight observed variables, we measured two latent variables: parental adverse experience (1–4 indicators) and childhood abuse history (5–8 indicators).

Cumulative risk measures were: educational attainment, drug use severity, repeat incarceration, and employment status. Educational attainment was an ordinal variable with four educational levels (less than high school, high school graduates, some college, and college graduates). Drug use severity measure was a three ordinal category variable (never used drugs, ever used drugs, and had been admitted to hospital or treatment program due to drug problems). Repeat incarceration was a continuous variable measuring the total number of incarcerations. Employment status was an ordinal variable (unemployed, employed part time, and employed full time), measuring current employment status during the 30 days before the index incarceration.

Age and race/ethnicity were controlled for, since predictors and outcome variables may potentially associated with women’s age and/or ethnicity. Age was a continuous variable and race/ethnicity was a dichotomous variable indicating being African American (vs. other).

Analysis

The analysis included all 235 responses from the original survey. Statistical software SPSS and LISREL 8 were used for the analyses. First, descriptive statistics were used to explore demographic, socioeconomic, and incarceration related characteristics of incarcerated women in the sample. Second, a structural equation model (SEM) was used to fit the conceptual model (Figure 1) and to explore direct and indirect effects of childhood events and cumulative disadvantages, predicting women’s current homelessness and sex-trade involvement. SEM is a useful tool to examine the appropriateness of theoretically drawn relationships using empirical data (Bentler & Stein, 1992). LISREL (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1996a) uses maximum likelihood methods providing chi-square and goodness of fit statistics that test the overall discrepancy between the data and the proposed conceptual model, by comparing the sample covariance matrix and the matrix reproduced by the parameters estimated in the model. If these matrices are not significantly different, the model can be considered to be a good representation of the data. Since variables used in the model were categorical, PRELIS 2 was used to create a heterogeneous matrix of polychoric correlations (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1996b).

First, a measurement model was tested for the latent variables. As stated, we assumed two associated latent variables (parental adverse events and adverse childhood experience), each of which was measured with four observed variables listed above. We then used the two latent variables to test the hypothesized model. The goodness of fit of the conceptual model was appraised with the robust comparative fit index (RCFI) and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). The RCFI, ranging from 0 to 1, reflects the improvement in fit of a hypothetical model over a model of complete independence among the measured variables (Bentler & Stein, 1992). The RMSEA indicates a reasonable error of approximation, and the model chi square statistic examines whether there is a significant difference between the model and the data (Browne, Cudeck, Bollen & Long, 1993). Good models have an RMSEA of .05 or less, and models with .10 or more have poor fit (Browne et al., 1993). A parsimony index for the models is also provided. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) evaluates baseline independence models that assume no relationships among the variables with parsimonious models. Another index for the level of goodness of fit is the Chi-square (χ2) to degrees of freedom (df) ratio. Lower values (generally smaller than 2) of χ2/df ratio are considered be a better fit between the model correlation matrix and the actual correlation matrix.

Results

The sample included 71.9% African American, 10.8% White, 6.9% Hispanic, and 10.4% other ethnic women (Table 1). The mean age was 35.7 years old (SD=8.9). More than 65% of women reported that their parents had problems with alcohol, drug abuse, mental health problems, or incarceration.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N=235)

| Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | African American | 166 (71.9) |

| White American | 25 (10.8) | |

| Other | 40 (17.3) | |

| Age | < 25 | 31 (13.6) |

| 25–34 | 79 (34.6) | |

| 35–44 | 79 (34.6) | |

| > 45 | 37 (17.1) | |

| All parental adverse events | 155 (65.7) | |

| Alcohol abuse | 125 (53.9) | |

| Drug abuse | 62 (27.0) | |

| Mental health problem | 61 (27.0) | |

| Incarceration | 54 (23.6) | |

| All childhood abuse history | 138 (59.2) | |

| Emotional | 116 (49.8) | |

| Neglect | 107 (45.9) | |

| Physical | 88 (37.8) | |

| Sexual | 88 (37.9) | |

| Education | Less than high school | 108 (46.4) |

| High school graduate | 75 (32.2) | |

| Some college | 39 (16.7) | |

| College graduate | 11 (4.7) | |

| Employment | Unemployed | 130 (56.8) |

| Part time | 42 (18.3) | |

| Full time | 57 (24.9) | |

| Drug use | Never used | 35 (14.0) |

| Ever used | 200 (86.0) | |

| Received treatment | 107 (49.8) | |

| Sex trade | Ever | 101 (44.7) |

| Current | 60 (26.3) | |

| Homelessness | Current | 66 (31.6) |

| Upon release | 79 (34.3) | |

| Number of incarcerations* | 4.9 (7.0, 1–60) | |

Mean (SD, range)

Fifty nine percent of women had a history of childhood abuse. More than 46% of women had less than high school education (or GED). Similarly, 56.8% were unemployed, and an additional 18% were employed part time. Nearly 50% of women reported that they had been previously admitted to a treatment facility for drug problems. More than 44% ever engaged in sex trade for money or other needs, 37% said they trade sex to meet their needs regularly, and 26% traded sex 30 days before incarceration. Nearly 32% were homeless or lived in unstable housing conditions, and 34% expected that they would be homeless upon release. On average, women had been incarcerated 4.9 times (SD=7.0).

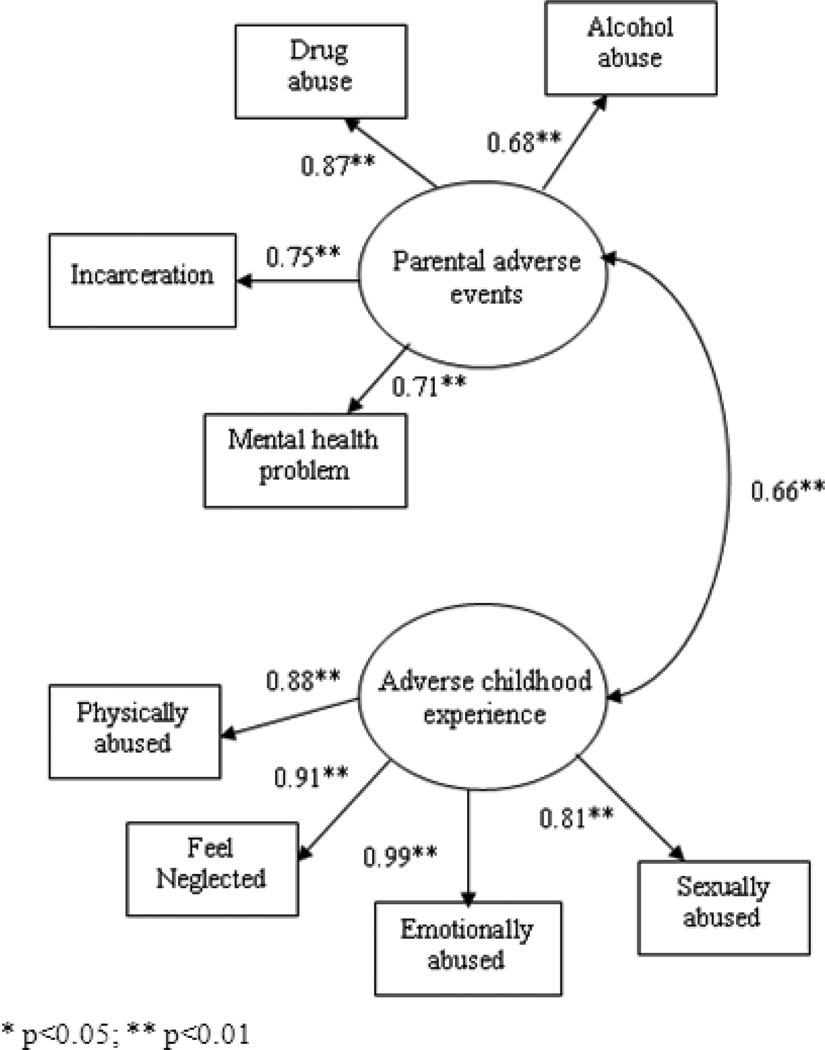

Figure 2 shows the results of the measurement model that developed the two latent variables. Several measures confirmed that the fit of this model was satisfactory. The chi-square statistic for the maximum likelihood of the full model was 29.01 (p = 0.07) with degree of freedom = 19, with a χ2/df ratio = 1.53. In addition, the RMSEA for the model was an acceptable 0.067 (CI, 0.0, 0.08), with model AIC = 63.01 and AGFI = 0.99.

Figure 2.

Latent variables model, completely standardized solution

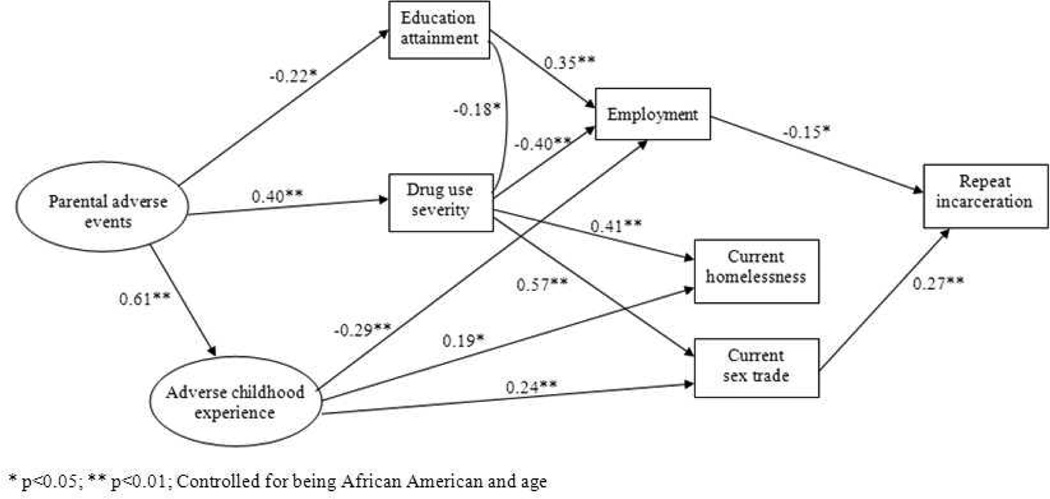

We then fitted the structural equation model using these two latent variables and the observed measures of the other variables of interest. Table 2 summarizes the unstandardized coefficients and standard errors for the covariance structure model. Race and age were controlled for in this model. The overall model showed an excellent fit: goodness of fit index (GFI) = 1.00, RCFI χ2 = 0.48 (p=1.0) with degree of freedom = 6, with a χ2/df ratio of 0.08, RMSEA = 0.0 with 90% CI (0.0, 0.0), independence model AIC = 516.74, and model AIC = 98.48. Figure 3 depicts the results of the structural equation model. Significant associations in the model are shown with solid lines (non-significant associations are not shown), along with coefficients and standard errors.

Table 2.

Unstandardized coefficients (standard errors) for the covariance structure model (N=235)

| Dependent Variable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable |

Childhood abuse history |

Education | Drug problem severity |

Current employment |

Current sex trade |

Current homelessness |

Number of incarceration |

| Parents’ adverse experience | 0.61** (0.08) | −0.22* (0.11) | 0.39** (0.12) | 0.26 (0.13) | −0.08 (0.10) | −0.13 (0.10) | |

| Childhood abuse history | 0.14 (0.09) | −0.003 (0.09) | −0.29** (0.10) | 0.24** (0.09) | 0.19* (0.09) | ||

| Education | −0.18* (0.07)§ | 0.35** (0.08) | |||||

| Drug problem severity | −0.18* (0.07)§ | −0.40** (0.10) | 0.57** (0.12) | 0.41** (0.13) | −0.04 (0.09) | ||

| Current employment | −0.03 (0.12) | −0.24 (0.13) | −0.15* (0.07) | ||||

| Current sex trade | −0.02 (0.10)§ | 0.27** (0.09) | |||||

| Current homelessness | −0.02 (0.10)§ | −0.03 (0.07) | |||||

| Number of incarceration | |||||||

| African American (vs. other) | −0.16** (0.04) | 0.02 (0.11) | −0.12 (0.11) | −0.12 (0.10) | −0.05 (0.13) | 0.09 (0.12) | −0.03 (0.07) |

| Age | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.09 (0.21) | −0.16* (0.07) | 0.01 (0.07) | −0.03 (0.05) | 0.36 (0.22) | |

| Error variance | 0.57** (0.11) | 0.95** (0.07) | 0.83** (0.09) | 0.63** (0.10) | 0.57** (0.10) | 0.66** (0.10) | 0.77** (0.16) |

| R2 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.23 |

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.0 (0.0; 0.0) | ||||||

| χ2 (RCFI) | 0.48 (p=1.00), df=6; χ2/df = 0.08 | ||||||

| Independence model AIC/Model AIC | 516.74/98.48 | ||||||

| Goodness of fit (GFI)/Adjusted GFI | 1.00/1.00 | ||||||

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

Error covariance.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model and completely standardized coefficients (shown significant paths only)

Consistent with the conceptual model, the SEM model (Figure 3) shows that women with parents who had adverse events were more likely to experience childhood abuse. Having parents with adverse events was negatively associated with educational attainment, but childhood abuse history did not have a significant effect on education level. Education level and drug use severity were negatively correlated. Having parents with adverse events, but not childhood abuse, was positively associated with drug use severity. Employment status was positively associated with education level, negatively associated with drug use severity and childhood abuse history. Both current homelessness and sex trade were positively associated with drug use severity and childhood abuse history, but not with parental adverse events, nor with employment status. Finally, repeat incarceration was negatively associated with employment and positively associated with current sex trade. Drug use severity did not have direct effect on repeat incarceration, but indirect effects through employment and sex trade.

Discussion

The study results showed that childhood adverse experiences had direct or indirect effects on each cumulative disadvantage measure and adulthood outcome. Interestingly parental adverse events had stronger effects on more immediate outcomes, such as education and drug abuse estimates; while childhood abuse history on more remote adulthood outcomes such as employment, homelessness, and sex trade. This finding suggests that growing up with parents who had their own issues affected women’s initial paths into high risk life contexts such as being exposed to childhood abuse, lack of education, and drug use. This supports previous findings regarding associations between household characteristics and school achievement in which parental involvement in children’s education has been shown to influence school performance and substance use behavior (Dannerbeck, 2005; Gonzalez-DeHass, Willems & Holbein, 2005). Previous studies suggest that parental incarceration and substance use may create household environments in which there is reduced adult supervision that can negatively affect children’s learning experiences and increase risks. The relative absence of parental involvement may also increase children’s exposure to risky social environments in which there are fewer disincentives to illicit behaviors such as substance use.

Abuse childhood experiences, on the other hand, appear to have longer term direct effects on women’s adult conditions, such as employment opportunities, homeless experiences homeless and engaging in sex trade. Studies have suggested that individuals with a childhood abuse history appear to develop symptoms indicating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Adams & Boscarino, 2006; Cohen, Deblinger, Mannarino & Steer, 2004). These studies report that childhood traumatic experiences alter children’s coping and emotional functioning. This finding may explain delayed effects of childhood abuse experiences in our study. Incarcerated women with childhood abuse experience may suffer from lingering emotional and psychosocial effects of PTSD due to childhood trauma (Bloom, Owen & Covington, 2003; Cohen, Mannarino & Knudsen, 2005; Pollack & Brezina, 2006; Zlotnick, Najavits, Rohsenow & Johnson, 2003). These studies consistently report that women with PTSD are more likely to exhibit low self-esteem, depression, and other mental health problems, and consequently experience functional difficulties. Co-occurring conditions of PTSD also often include adulthood sexual victimization, substance abuse, and incarceration (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; Felitti et al., 1998; Wechsberg et al., 2003). These findings imply potential mediating effects of psychosocial conditions between childhood abuse and adult adverse outcomes. These were not examined in our study, and will require further research. Obviously, parental adversity and childhood abuse experiences are closely associated, and differential effects of these childhood events warrant further research.

In addition, our finding regarding parental adverse events has an additional implication for children of incarcerated women, considering over 80% of female inmates are mothers of dependent children. The intergenerational impact of women’s experience with substance use, incarceration, and the psychosocial consequences is dire (Dellaire, 2007; Huebner & Gustafson, 2007; Mumola, 2000; Poehlmann, 2005; Travis & Waul, 2003). The potential for intergenerational cycles of substance abuse and incarceration needs to be further explored.

Our study findings are particularly important, given that the effects of childhood adverse events were demonstrated among incarcerated women, who are a highly homogenous group of disadvantaged individuals. Incarcerated individuals are already marginalized and living in disadvantaged neighborhoods. And incarceration may damage social and human capital. With an often severe lack of resources, incarcerated individuals may be forced further into illicit activities in order to survive. This may explain high rates of homelessness and sex trade among incarcerated women. Our findings suggest that recidivism may be at least in part a function of economic difficulties. Women who were unemployed and engaged in sex trade were more likely to have been incarcerated multiple times.

Having severe drug abuse problems also seems to affect a myriad of adulthood exposures to disadvantages, including lack of employment, homelessness, and sex trade, each of which in turn may increase the likelihood of recidivism. This highlights the significance of drug abuse among incarcerated women. Many researchers have asserted that substance abuse treatment plays a critical role in interventions for the incarcerated population (Belenko, 2006; Bouffard & Taxman, 2000; Johnson, 2006; Severance, 2004). Providing effective substance abuse treatment programs would seem to be a key element to securing jobs, reducing homelessness, risky sexual behaviors, and recidivism.

The life course perspective provides a unique approach to better understand the long lasting cumulative effects of negative life experiences on future disadvantages among incarcerated women. Female inmates’ exposure to adverse life events in early life may initiate trajectories that help explain current life contexts. The life course perspective may also be particularly important in designing interventions for incarcerated women. Interventions focusing on cross sectional views of risk exposure may exclude important aspects of the cumulative life experiences that shape the contemporary life contexts of these women.

Limitations

Although our findings help provide a better understanding of female inmates’ experiences of adulthood homelessness and survival sex, several limitations exist in this study. First, the study was cross-sectional, and information regarding childhood experiences was collected retrospectively. There is always a threat of recall bias with retrospective data collection (Chouinard & Walter, 1995; Hassan, 2006). Such bias could operate in several directions, as some women might have more readily remembered their more traumatic experiences, while others might have suppressed their most painful memories, resulting in under-reporting of some experiences. To minimize this threat, we developed a path model to more closely approximate temporal associations by using only questions that had obvious temporal relationships, such as childhood experiences vs. current conditions. However, the inherent limitations of these data could not be entirely eliminated.

Second, selection bias might be present, since survey respondents in the original survey were a sample of volunteers. Therefore, the sample may be less representative of general incarcerated women. Those who decided to participate in the study may have been physically healthier or less depressed; also, it is plausible that those who felt that they might be stigmatized if they reported their experiences might have been less likely to participate in the survey. However, compared to the characteristics of incarcerated women in Cook County Jail, the potential selection bias may be less prominent. Compared to the national level report on incarcerated women, our sample seems to be fairly representative of incarcerated women in general. Overall in 2005, for example, 72% of incarcerated women were African American, which was close to our sample, of which 72% was African American. Similarly, the median age of the sample was 35 years old, and the overall median age of all women incarcerated during 2005 was 34.8 years. Moreover, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (Snell, 1994), 53.3% was unemployed (compared to 56.8% in our sample) and 55% had high school or more education (compared to 53.6% in our sample).

Third, the survey data is self reported information that is subject to social desirability bias problems; respondents might have under-reported what they perceived to be undesirable answers or over-reported what they wanted to highlight. No research, however, has reported that this type of bias is more prevalent among incarcerated individuals than in the general population. For example, Nelissen (1998) concluded that there was little evidence of social desirability bias in self-reported opinions about correctional facilities. Similarly, Heimer and others (2005) found that the discrepancy between self-reported illicit drug use and actual urine testing among prison inmates was not considerable. However, further research is needed on this topic.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our findings provide valuable empirical evidence regarding the associations between the childhood and later life experiences of incarcerated women. These findings provide evidence regarding pathways by which childhood household characteristics may affect women’s risk of childhood abuse experiences and subsequent life experiences. As hypothesized, childhood environment may be associated women’s life conditions, and also increase the likelihood of experiencing childhood physical and sexual abuses. The study results are particularly noteworthy, considering the fact that the association was evident within this highly disadvantaged population.

Incarcerated women suffer from poverty and lack of life options, in which they are exposed to multiple risks. These issues tend to cluster in certain populations and neighborhoods, sharing common contributing factors that are deeply embedded in these women’s life contexts. Thus, interventions are necessary to address multiple issues, including socioeconomic disparities and other co-occurring conditions. Without a stable means to meet their survival needs, reducing health risks may not become a high priority. Currently, discharge planning or service linkages for incarcerated women are severely lacking (Baskin, Braithwaite, Eldred & Glassman, 2005; Freudenberg, Daniels, Crum, Perkins & Richie, 2005; James & Glaze, 2006; Vlahov & Putnam, 2006). When they are released without any provision, these women often have no other option but to return to the high risk environment and behaviors that initially led to their incarceration. In addition, incarceration may exacerbate women’s conditions, disrupting already frail support and resources by removing women from their social networks and support systems.

To effectively improve the health outcomes of incarcerated women, and to reduce recidivism, therefore, interventions need to address these complex and difficult life experiences. The successful reintegration of inmates into the community is hampered by lack of discharge planning (Lam, Wechsberg & Zule, 2004; Robertson et al., 2004), which may help inmates overcome barriers and prepare clear and practical action plans as to how to obtain community resources that may smooth their reintegration into the community.

References

- Adams R, Boscarino J. Predictors of PTSD and delayed PTSD after disaster: the impact of exposure and psychosocial resources. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2006;194(7):485–493. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000228503.95503.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin M, Braithwaite R, Eldred L, Glassman M. Introduction to the special supplement: prevention with persons living with HIV. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(1) Suppl. A:1–5. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.2.1.58698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S. Assessing Released Inmates for Substance-Abuse-Related Service Needs. Crime & Delinquency. 2006;1:94–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson V, Allen K. The Life Course Perspective Applied to Families over Time. In: Boss P, Doherty W, LaRossa R, Schumm W, Steinmetz S, editors. Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. New York: Plenum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P, Stein J. Structural equation models in medical research. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1992;1:159–181. doi: 10.1177/096228029200100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen B, Covington S. Gender-responsive strategies: Research, practice and guiding principles for women offenders. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger K, Patterson C. Pathways from child maltreatment to internalizing problems: Perceptions of control as mediators and moderators. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:913–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boney-McCoy S, Finkelhor D. Is youth victimization related to trauma symptoms and depression after controlling for prior symptoms and family relationships? A longitudinal prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1406–1416. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth B, Sullivan G, Koegel P, Burnam A. Vulnerability factors for homelessness associated with substance dependence in a community sample of homeless adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(3):429–452. doi: 10.1081/ada-120006735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffard J, Taxman F. Client Gender and the Implementation of Jail-Based Therapeutic Community Programs. Journal of Drug Issues. 2000;4:881–900. [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Miller B, Maguin E. Prevalence and severity of lifetime physical and sexual victimization among incarcerated women. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 1999;22(3–4):301–322. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(99)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne M, Cudeck R, Bollen K, Long J. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park: Sage Publication; 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse Childhood Experiences. [Retrieved November 17, 2009];2006 from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/ace.

- Chicago Coalition for the Homeless. Unlocking options for women: A survey of women in Cook County Jail. Chicago IL: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chouinard E, Walter S. Recall bias in case-control studies: an empirical analysis and theoretical framework. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1995;48(2):245–254. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00132-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth S. Child maltreatment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Deblinger E, Mannarino A, Steer R. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Mannarino A, Knudsen K. Treating sexually abused children: 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley R, Chase-Lansdale P. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood: Recent evidence and future directions. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):152–166. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington S, Kohen J. Women, alcohol, and sexuality. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse. 1984;4(1):41–56. doi: 10.1300/J251v04n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E, Saito Y. Trends in health life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:1629–1641. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannerbeck A. Differences in Parenting Attributes, Experiences, and Behaviors of Delinquent Youth with and without a Parental History of Incarceration. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2005;(no. 3):199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Dellaire D. Incarcerated mothers and fathers: A comparison of risks for children and families. Family Relations. 2007;56:440–453. [Google Scholar]

- Dube S, Felitti V, Dong M, Chapman D, Giles W, Anda R. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Halpern C, Wechsberg W. Correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among women who use crack cocaine. AIDS Education and Prevention : Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2006;18(5):420–429. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. Life Course Dynamics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Tarui N. Child Maltreatment, Family Characteristics, and Educational Attainment: Evidence from Add Health Data. [Retrieved November 17, 2007];2009 from http://www.economics.hawaii.edu/research/seminars/08-09/03_06_09.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V, Anda R, Nordenberg D, Williamson D, Spitz A, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D, Horwood L, Lynskey M. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;34(10):1365–1374. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom D, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, Gilmer T, Bailey A, Golshan S, Garcia P, Unutzer J, Hough R, Jeste D. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):370–376. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie B. Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1725–1736. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilfus M. From victims to survivors to offenders: Women’s route of entry and immersion into street crime. Women & Criminal Justice. 1992;4:63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Goebert D, Bell C, Hishinuma E, Nahulu L, Johnson R, Foster J, Carlton B, Mcdermott J, Chang J, Andrade N. Influence of family adversity on school-related behavioural problems among multi-ethnic high school students. School Psychology International. 2004;25(2):193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-DeHass A, Willems P, Holbein M. Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educational Psychology Review. 2005;17:99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg G, Rosenheck R. Homelessness in the state and federal prison population. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2008;18:88–103. doi: 10.1002/cbm.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld L, Snell T. Women Offenders. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2000. (NCJ 175688) [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. Women survivors of childhood abuse: the impact of traumatic stress on education and work. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2000;21(5):443–471. doi: 10.1080/01612840050044230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammett T, Harmon M, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1789–1794. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Beck A. Prisoners in 2004. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2005. (NCJ 210677) [Google Scholar]

- Hassan E. Recall bias can be a threat to retrospective and prospective research designs. The Internet Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;3(2):339–412. [Google Scholar]

- Heimer R, Catania H, Zambrano J, Brunet A, Ortiz A, Newman R. Methadone maintenance in a men's prison in Puerto Rico: A pilot program. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2005;11(3):295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington E, Bridges M, Insabella G. What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children's adjustment. American Psychologist. 1998;53:167–184. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz A, Widom C, McLaughlin J, White H. The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: A prospective study. Journal of health and social behavior. 2001;42:184–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner B, Gustafson R. The effect of maternal incarceration on adult offspring involvement in the criminal justice system. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2007;3:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- James D. Profile of jail inmates, 2002. Washington DC: US Department of Justice; 2004. (NCJ 201932) [Google Scholar]

- James D, Glaze L. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes W. The Relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Urban Education. 2007;42(1):82–110. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson H. Concurrent Drug and Alcohol Dependency and Mental Health Problems among Incarcerated Women. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2006;39(2):190–217. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson H, Young D. Addiction, Abuse, and Family Relationships: Childhood Experiences of Five Incarcerated African American Women. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2002;4:29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog K, Sorbom D. Lisrel 8: User's reference guide. Chicago Scientific Software International (SSI); 1996a. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog K, Sorbom D. Prelis 2: User's reference guide. Chicago Scientific Software International (SSI); 1996b. [Google Scholar]

- Karberg J, James D. Substance dependence, abuse, and treatment of jail inmates, 2002. Washington DC: US Department of Justice; 2005. (NCJ 209588) [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Wilkinson R. Income Inequality and Health: A Reader. New York: New Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett K. The health effects of childhood abuse: four pathways by which abuse can influence health. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:715–729. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett K, Eckenrode J. The effects of neglect on academic achievement and disciplinary problems: a developmental perspective. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Bulik C, Silberg J, Hettema J, Myers J, Prescott C. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinard E. Psychosocial resources and academic performance in abused children. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1999;21:351–376. [Google Scholar]

- Kruttschnitt C, Gartner R, Hussemann J. Female Violent Offenders: Moral Panics or More Serious Offenders? The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2008;1:9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kuno E, Rothbard A, Averyt J, Culhane D. Homelessness among persons with severe mental illness in an enhanced community-based mental health system. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(8):1012–1016. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.8.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam W, Wechsberg W, Zule W. African-American women who use crack cocaine: a comparison of mothers who live with and have been separated from their children. Child abuse & neglect. 2004;28(11):1229–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann E, Kass P, Drake C. Risk factors for first-time homelessness in low-income women. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R. Violence and the life course: The Consequences of Victimization for Personal and Social Development. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001;27:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak L. Medical Problems of Jail Inmates. Washington DC: US Department of Justice; 2006. (NCJ 210696) [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak L. HIV in Prisons, 2007–8. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. (NCJ 228307) [Google Scholar]

- Metraux S, Culhane D. Recent incarceration history among a sheltered homeless population. Crime & Delinquency. 2006;52(3):504–517. [Google Scholar]

- Miech R, Hauser R. Socioeconomic status (SES) and health at midlife: a comparison of educational attainment with occupation based indicators. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min M, Farkas K, Mommes S, Singer L. Impact of childhood abuse and neglect on substance abuse and psychological distress in adulthood. Journal of traumatic stress. 2007;20(5):833–844. doi: 10.1002/jts.20250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Hu P. Physical Impairment and the Diminishing Effects of Income. Social Forces. 1996;74(3):1073–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Mumola C. Incarcerated parents and their children. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2000. (No. 182335) [Google Scholar]

- Mumola C, Karberg J. Drug use and dependence, state and federal prisoners 2004. Washington DC: US Department of Justice; 2006. (NCJ 213530) [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington D. Parental imprisonment: effects on boys' antisocial behaviour and delinquency through the life-course. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(12):1269–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Correctional Health. The Health Status of Soon-to-be-Released Inmates: A Report to Congress. Chicago, IL: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen P. The reintegration process from the perspective of prisoners: Opinions, perceived value and participation. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. 1998;6:211–234. [Google Scholar]

- O'Conner T, Dunn J, Jenkins J, Pickering K, Rasbash J. Family settings and children's adjustment: differential adjustment within and across families. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:110–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rand A. The Precious and the Precocious: Understanding Cumulative Disadvantage and Cumulative Advantage over the Life Course. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:230–238. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patall E, Cooper H, Robinson J. Parent involvement in homework: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research. 2008;78(4):1039–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. Children's Family Environments and Intellectual Outcomes during Maternal Incarceration. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;5:1275–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack S, Brezina K. Negotiating Contradictions: Sexual Abuse Counseling with Imprisoned Women. Women & Therapy. 2006;3–4:117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Puisis M, Levine W, Mertz K. Overview of sexually transmitted diseases in correctional facilities. In: Puisis M, Anno B, Cohen R, editors. Clinical practice in correctional medicine. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998. pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen L, Tremblay R. Patterns of boys' social adjustment in two cultures and at different ages: a longitudinal perspective. Int. J. Behav. Devel. 1992;15:527–553. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam F. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):269–278. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Clarke J, Silverman J, Rose J, Rosengard C, Hebert M, Stein M. Violence against women associated with arrests for sex trade but not drug charges. International journal of law and psychiatry. 2006;29(3):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reback C, Kamien J, Amass L. Characteristics and HIV risk behaviors of homeless, substance-using men who have sex with men. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(3):647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson M, Clark R, Charlebois E, Tulsky J, Long H, Bangsberg D, Moss A. HIV seroprevalence among homeless and marginally housed adults in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1207–1217. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C, Wu C. The Links Between Education and Health. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Couture H, Sabol W. Prison Inmates at Midyear 2007. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2008. (NCJ 221944) [Google Scholar]

- Settersten R. Age structuring and the rhythm of the life course. In: Mortimer J, Shanahan M, editors. Handbook of the Life Course. New York: Plenum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Severance T. Concerns and Coping Strategies of Women Inmates concerning Release: It's Going to Take Somebody in My Corner. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2004;4:73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Silbert M. Sexual child abuse as an antecedent to prostitution. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1981;5:407–411. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman A, Reinherz H, Giaconia R. The long-term sequelae of child and adolescent abuse: A longitudinal community study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1996;20(8):709–723. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade E, Wissowb L. The Influence of Childhood Maltreatment on Adolescents' Academic Performance. Economics of Education Review. 2007;26(5):604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell T. Women in prison. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon C, Serres F. Effects of parental verbal aggression on children’s self-esteem and school marks. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:339–351. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer K, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. The Long-term Health Outcomes of Childhood Abuse: An Overview and a Call to Action. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):864–870. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20918.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Chapman T, Chapman D, Kaiser A, Hancock T. Cumulative Risk and Low-Income Children's Language Development. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2004;24(4):227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Travis J. Defining a Research Agenda on Women and Justice in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Women & Criminal Justice. 2007;2–3:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Travis J, Waul M. Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families and communities. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Putnam S. From corrections to communities as an HIV priority. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):339–348. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Lam WK, Zule W, Hall G, Middlesteadt R, Edwards J. Violence, homelessness, and HIV risk among crack-using African-American women. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38(3–6):669–700. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser S, Dilworth S, Neilands T, Cohen J, Bansberg D, Riley E. Gender-specific correlates of sex trade among homeless and marginally housed individuals in San Francisco. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(4):736–740. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West H, Sabol W. Prison Inmates at Midyear 2008 - Statistical Tables. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. (NCJ 225619) [Google Scholar]

- Widom C. Child abuse, neglect and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence and child maltreatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom C, Kuhns J. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(11):1607–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt G, Guthrie D, Notgrass C. Differential effects of women’s child sexual abuse and subsequent sexual re-victimization. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:167–173. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Najavits L, Rohsenow D, Johnson D. A cognitive-behavioral treatment for incarcerated women with substance abuse disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a pilot study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25(2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]