Summary

Epigenetic mechanisms control gene transcription primarily through regulating chromatin structures and DNA methylation. Transcription factors can also affect gene transcription through binding of the key transcriptional machinery to the gene promoter. These factors normally jointly influence the transcriptional processes, leading to silencing or activation of gene expression. A novel technique has been recently explored in our laboratory, which is a combination of conventional chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with bisulfite methylation sequencing assays, so called ChIP-BMS. This technique provides precise information of DNA methylation status at the selected DNA fragments precipitated by the antibodies to histone molecules or transcription factors of interest. This method also helps to investigate the interactions between histone modification and DNA methylation, and how this cross-talking can affect gene expression. More importantly, it is easy to determine potential methylation-sensitive transcription factors that influence transcription mainly depending on methylation status of the binding sites. In this chapter, we will discuss the detailed procedures of this novel technique and its broad application in epigenetic and genetic fields.

Keywords: DNA methylation, histone modification, transcription factor, bisulfite sequencing, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), ChIP-BMS

1. Introduction

The epigenetic changes involving DNA methylation and chromatin structures profoundly affect both physiological and pathological processes mainly via regulating gene transcription. DNA methylation, for example, most often occurs at a cytosine base located 5′ to a guanosine (CpG dinucleotide), which is found mainly located in the proximal promoter regions of almost half of the genes in the mammalian genome (1). DNA methylation interferes with gene transcription principally though the prevention of the binding of the basal transcriptional machinery and of ubiquitous transcription factors to the gene promoters (2, 3). This effect can be implemented though the direct and indirect mechanisms of DNA methylation. For the direct mechanism, methylated CpG sites can block the binding of certain transcription factors that are sensitive to the methylation status in their recognition sites, resulting in silenced transcription (4–10). The indirect mechanism is more involved in the accessibility of the transcription repressor complex at the hypermethylated promoter modulated by a group of proteins such as methyl-cytosine-binding proteins (MBPs) (11–12). As a consequence, DNA hypermethylation is mainly associated with gene repression, whereas DNA hypomethylation at the promoter allows gene expression.

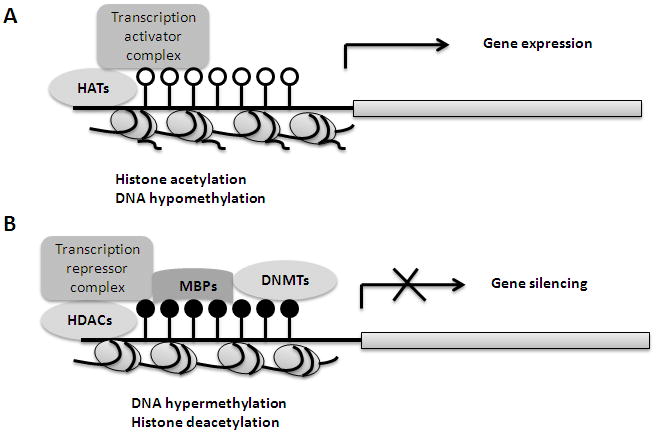

Another important epigenetic mechanism is chromatin modification, which also plays a key role in controlling gene transcription (13). Different types of chromatin modification patterns have been identified such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination on the specific lysine residues of core histone tails (14). Two main mechanisms by which these modifications on chromatin structure influence gene transcription are well documented. One is that the alteration of chromatin packing can directly change the conformation of the DNA polymer, thus facilitating the accessibility of DNA-binding proteins such as transcription factors to the core gene regulatory region. The other mechanism is involved with the recruitment of the transcription factor machinery triggered by the altered chemical moieties on the nucleosome surface during chromatin remodeling (15, 16). Therefore, epigenetic events working on gene transcription primarily rely on regulation of a dynamic equilibrium between the conformation change of DNA or chromatin and binding ability of transcription factors to the core gene regulatory region. This cross-link working model is more likely to generate a complicated interaction between the epigenetic and genetic mechanisms for gene transcription through a “bridge”, transcription factors (Fig. 1). For example, many methylation-sensitive transcription factors have been identified in which their binding abilities predominately depend on the methylation status of the consensus binding sites on the gene promoter by which binding gene expression will be turned on or off (Table 1.). Thus, a new method that can provide the detailed information of these interaction patterns is needed.

Fig. 1.

Crosstalking between chromatin modifications and DNA methylation through transcription factors during gene transcription regulation. A. Histone acetylation by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and DNA hypomethylation can assemble active transcription factors on gene regulatory regions and induce gene expression. B. Hypermethylated CpG sites by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) is bound by methyl-cytosine-binding proteins (MBPs), with the presence of histone deacetylases (HDACs), which recruits the complex of repressive transcription factors to the gene promoter, leading to gene repression.

Table 1.

Selective Methylation-sensitive Transcription Factors

| Transcription Factors | E2F-1 | c-Myc | CTCF | Sp1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putative recognition site * | TTTCCCGC | E-box CACGTG | CCGCGCGGCGGCAG | ACTCCGCCCG |

| Regulated gene | Cyclin E, ATM, p73, hTERT | NFκB, TGFβ, hTERT | c-MYC, Igf2, hTERT | Housekeeping genes |

| Binding preference | hypomethylation | hypomethylation | hypomethylation | hypomethylation |

| Methylation effects on transcription | Repression | Repression | Repression | Activation |

| Primary function | Cellular cycle regulation | Cell proliferation Oncogenesis | Imprinting regulation Tumor suppression | Universal transcription regulation |

| Reference | 9, 10 | 7 | 4, 5 | 8 |

The consensus sequence of methylation-sensitive transcription factors contains at least one CpG dinucleotide (bolded), which is recognized by the methyltransferase and methylation regulatory proteins, thus influencing binding ability of these transcription factors.

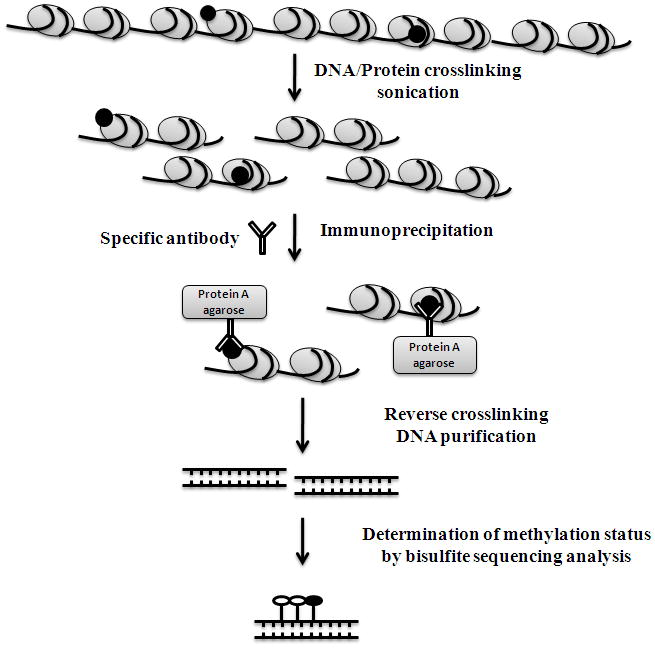

Bisulfite genomic sequencing analysis is classic technology for detection of DNA methylation by which an unmethylated cytosine residue in single-stranded DNA will be converted to uracil and methylated cytosine will remain as cytosine (17). The precise DNA methylation information will be conveyed by the subsequent PCR amplification and sequencing. The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay is commonly used in determination of chromatin modification patterns or transcription factor binding (18). Several new technologies have recently emerged on the basis of the ChIP assay on a genome-wide scale, such as ChIP on chip (19, 20). However, there is no available technology to further test the DNA methylation patterns on the ChIP DNA. Recently, we developed a novel ChIP-bisulfite methylation sequencing (ChIP-BMS) approach on the basis of combining the conventional ChIP and bisulfite methylation sequencing assays (10). This new technology detects the methylation status of ChIP DNA pulled-down by a specific antibody (histone markers or transcription factors) (Fig. 2). ChIP-BMS is believed to provide an excellent opportunity to investigate the interaction patterns between histone modification and DNA methylation, transcription factor binding and methylation of recognition sites, as well as multiple interactions between genetic and epigenetic factors. It could be widely used in various research fields such as determination of the cross-talking between histone modification and DNA methylation, candidate methylation-sensitive transcription factors and epigenetic regulation of gene transcription.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the procedure of chromatin immunoprecipitation-bisulfite methylation sequencing (Chip-BMS).

2. Materials

2.1. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

2.1.1. DNA-protein Crosslinking and Sonication

37% Formaldehyde.

Cold 1 × PBS buffer.

2.5 M Glysine.

SDS lysis buffer (Millipore).

Protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma).

Ultrasonic homogenizer (Biologics. Inc).

Agarose gel and electrophoresis apparatus.

Ethidium bromide.

2.1.2. Immunoprecipitation

ChIP dilution buffer (Millipore).

Salmon sperm DNA/Protein A Agarose-50% slurry (Millipore).

Specific antibody (histone marker or transcription factor) and control mouse IgG.

2.1.3. Wash

Low salt immune complex wash buffer (Millipore).

High salt immune complex wash buffer (Millipore).

LiCl immune complex wash buffer (Millipore).

TE buffer.

Shaker at 4 °C at room temperature (RT).

Microcentrifuge.

2.1.4. DNA Elution and Reverse Crosslinking

ChIP elution buffer (freshly prepared): 0.1 M NaHCO3 and 1% SDS.

5 M NaOH.

Incubator at 65 °C.

2.1.5. Immunoprecipitated DNA Purification

Proteinase K buffer (freshly prepared): 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.5; 5 mM EDTA, 10 μg/μl Proteinase K.

Wizard DNA clean-up system (Promega).

Disposable 5-ml lure-lock syringes.

Deionized water or TE buffer.

2.1.6. ChIP PCR

Regular 2 × PCR Mastermix (Promega) for semi-quantitative PCR and SYBR Green qPCR Supermix (Invitrogen) for Realtime-quantitative PCR.

Specific ChIP primers.

Agarose gel and electrophoresis apparatus.

Roche Realtime LC480.

2.2. ChIP-Bisulfite Methylation Sequencing (ChIP-BMS)

2.2.1. Bisulfite Reaction

Quantification of Chip-purified DNA: Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad).

Bisulfite reaction kit, EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen).

Wizard DNA clean-up system (Promega) for purification of bisulfite-treated DNA.

Disposable 5-ml lure-lock syringes.

Deionized water or TE buffer.

2.2.2. PCR Purification, Cloning and Sequencing Analysis of ChIP DNA Fragment

Regular 2 × PCR Mastermix (Promega).

QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) for purification of PCR product.

QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) for purification of target PCR fragment from multiple unspecific PCR products.

pGEM-T Easy vector system II (Promega).

For bacterial culturing and positive cloning selection, bacto tryptone (BD), yeast extract, sodium chloride, ampicillin solution, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), X-Gal (Bio-Rad), and bacterial shaker incubator at 37 °C are required.

QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen).

ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer.

3. Methods

3.1. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

3.1.1. DNA-protein Crosslinking and Sonication

The method described below is suitable for analysis of cultured cells. The cells grown in 100 mm culture plates should reach 90% confluence (around 1 × 106 cells) prior to the harvest point. To obtain adequate ChIP DNA for the subsequent bisulfite sequencing analysis, several extra plates of cells may be required (see Note 1). All procedures should be performed on ice to prevent potential protein loss.

Add 270 μl of 37% formaldehyde to 10 ml of growth medium (1% final concentration) for crosslinking for 10 min in the incubator at 37 °C (see Note 2).

Add 0.5 ml 2.5 M glycine (0.125 M of final concentration) to the medium to quench the crosslinking and incubate at room temperature for 5 min.

Remove the medium and wash the attached cells with cold PBS twice.

Scrape the cells from the plates to a micro-tube and centrifuge at 12,000 rpm to pellet the cells.

Discharge the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet with 500 μl in SDS lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor, then incubate on ice for 10 min.

Shear DNA using an Ultrasonic homogenizer at 20–30% output. Each sample is sonicated for 4–6 cycles (10 sec sonication, 30 sec pause). The conditions for sonication should be carefully optimized. The optimal corsslinked chromatin DNA should be sheared at 200–1000 base pairs in length as determined by routine electrophoresis gel analysis (see Note 3). This sheared DNA sample can be stored in −80 °C for half a year or in liquid nitrogen for longer storage.

3.1.2. Immunoprecipitation of Crosslinked Chromatin DNA/Protein

Dilute 100 μl of sheared DNA/protein sample from Subheading 3.1.1., step 6 with 900 μl 10 × ChIP dilution buffer containing protease inhibitor. A small fraction of chromatin DNA after dilution (~ 50 μl) will be extracted for the future use of internal control (input). Proceed to Subheading 3.1.3., step 1 for continuation of processing of the input.

Optimally, a pre-clean step should be included prior to immunoprecipitation in order to remove the nonspecific background. In this step, 50 μl of Protein A Agarose slurry is added to the chromatin followed by incubation for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation (see Note 4).

Spin down the agarose beads and remove the supernatant to a new micro-tube.

Add the specific antibody (5–10 μg) to the supernatant and incubate overnight at 4 °C with rotation (see Note 5).

Incubate 60 μl of Protein A Agarose with the chromatin DNA/protein complex for 2–3 h at 4 °C with rotation. Briefly spin down the agarose and discharge the supernatant (see Note 6).

-

Wash the Protein A Agarose-antibody/chromatin complex by suspending the agarose with the following commercially-available wash buffers in sequence at room temperature with rotation and collect the agarose beads by brief centrifugation (3000 rpm).

Low Salt Immune Complex Wash Buffer, 1 ml, one wash, 10 min.

High Salt Immune Complex Wash Buffer, 1 ml, one wash, 10 min.

LiCl Immune Complex Wash Buffer, 1 ml, one wash, 10 min.

TE Buffer, 1 ml, two washs, 10 min.

After the final wash with TE, the agarose is incubated with 250 μL freshly made ChIP Elusion buffer for 20 min at room temperature with rotation for twice. The supernatant containing specifically pulled down-chromatin DNA/protein complex will be collected together for a total volume of 500 μl.

3.1.3. Purification of Immunoprecipitated Chromatin DNA and ChIP-PCR

Reverse crosslinking: Add 20 μl 5 M NaCl to the 500 μl eluent. Add 2 μl 5 M NaCl to the input DNA from Subheading 3.1.2., step 1. Incubate the eluent and input at 65 °C for 6 h or overnight.

Add 30 μl of freshly made Proteinase K buffer to the eluent. Add 3 μl of Proteinase K buffer to the input. Incubate the eluent and input at 45 °C for 1 h.

We routinely use the Wizard DNA clean–up kit from Promega to purify the immunoprecipitated chromatin DNA. The detailed procedure involving this step is followed by the manufacturer’s protocol.

The purified immunoprecipitated (IP) DNA is ready for PCR analysis. ChIP-PCR is performed as a regular PCR reaction. To verify the ChIP-PCR results, appropriate controls should be set up along with the whole procedure (see Note 7). The PCR results can be determined by gel-based electrophoresis as a semiquantitative PCR, or if possible, a quantitative PCR can be performed when the specific realtime ChIP primers are available. The final results will be normalized to input DNA and calibrated to levels in control samples if necessary.

The ChIP-PCR results are considered as positive binding at the selected region of the DNA when the abundance of the DNA band is more than 10-fold higher than the negative control. Therefore, the DNA methylation status of this selected binding region can be detected by the use of IP DNA (see Note 8).

3.2. Bisulfite modification, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

Quantification of IP DNA: at least 2 μg of IP DNA is required for bisulfite treatment per sample. Several attempts may be needed to obtain an adequate amount of IP DNA (see Note 1).

Use the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) to convert and purify the bisulfite modified-IP DNA. The detailed protocol is provided by the manufacturer’s protocol (see Note 9).

ChIP-Bisulfite PCR amplification can be performed as a normal PCR reaction. As a general rule for any PCR reaction, the PCR conditions should be carefully optimized (see Note 10). The PCR results will be verified by gel-based electrophoresis and a single, bright and specific band will be considered as a successful PCR amplification.

After a successful PCR amplification, PCR products should be purified by using commercially available kits such as QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) or QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) which can help purify the target PCR product from multiple nonspecific PCR bands.

The purified PCR products can be directly sequenced. Sub-cloning sequencing is necessary to observe methylation patterns of the single molecules. We prefer to use the pGEM-T Easy vector system II (Promega) for cloning purposes and all detailed procedures are followed by the manufacturer’s protocol.

3.3. Data Interpretation

Following successful bisulfite PCR amplification or sub-cloning procedures, IP DNA mehtylation status can be interpreted by subsequent sequencing analysis. After bisulfite treatment, all unmethylated cytosines (C) convert to thymine (T) and the presence of C-peaks indicate the presence of 5mC in the genome. If a band appears in both the C- and T-peaks, then this indicates partial methylation or potentially incomplete bisulfite conversion. For example, to observe the methylation status of the binding site of E2F-1, a methylation-sensitive transcription factor, ChIP assay is performed followed by a bisulfite sequencing analysis on IP DNA. Therefore, by comparing the original DNA sequence, the methylation status of E2F-1 binding sites with E2F-1 binding on certain gene promoters can be determined by bisulfite sequencing analysis. Alternatively, the proportion of methylation changes of E2F-1 binding sites with E2F-1 binding can be interpreted by comparing a large segment containing the E2F-1 binding site for DNA methylation changes.

Table 2.

Interpretation of ChIP Results

| Primers | Positive control | Negative control | “No antibody” control | Sample | Internal control | Indicated consequence | Solution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control primer | GAPDH | + | − | − | n/a | + | Good working system | Proceed to testing the specific primer |

| GAPDH | + | +/slight | − | n/a | + | Weak working system | Need to adjust the crosslinking and sonication conditions | |

| GAPDH | + | + | + | n/a | + | Potential contamination | Change PCR reagent | |

| Specific primer | Specific primer | n/a | − | − | + | + | Good result | n/a |

| Specific primer | n/a | +/slight | − | + | + | Nonspecific antibody | Need to adjust annealing temperature or other PCR conditions; change antibody | |

| Specific primer | n/a | + | + | + | + | Potential contamination | Change PCR reagent | |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA 129415), the Susan G. Komen for the Cure and a Postdoctoral Award (PDA) sponsored by the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR).

Footnotes

One trial of ChIP assay (1 × 106) will yield about 1 μg of IP DNA. However, IP DNA has been sheared to 200–1000 bp by sonication, which will increase DNA damage during bisulfite modification. Therefore, ChIP-BMS may require more DNA (> 2 μg) for the bisulfite reaction to compensate for the potential DNA loss. Several repeat ChIP reactions will help to collect enough IP DNA for the bisulfite reaction if necessary.

The conditions of crosslinking should be carefully optimized. The amount of formaldehyde, the fix time and incubation temperature should be determined for different types of cells, as well as proteins and target DNA regions of interest (21). For high-affinity DNA binding proteins such as histones, the native chromatin can be used for the ChIP assay (22).

Optimal conditions for sonication are required that guarantee the sheared and crosslinked DNA will be in the 200–1000 bp range. Variable parameters such as processing time and the power setting should be adjusted every time if the cell type and cell lysis concentration have been altered. Agarose-gel based electrophoresis can be used to determine the desired length of sheared DNA.

If the enrichment of ChIP product is weak, this step can be omitted to reduce subsequent loss of DNA/protein complexs.

The primary antibody for immunoprecipitation should specifically recognize the protein of interest. Moloclonal antibodies are desired due to their specificity, whereas polyclonal antibodies can also be applied if no monoclonal antibody is available although nonspecific binding may occur with the use of a polyclonal antibody. The appropriate amount of primary antibody for immunoprecipitation should be determined to yield enough IP DNA. Normally, 2–5 μg of antibody will produce enough IP DNA, but low specific antibody may reduce the amount of IP DNA.

Protein A Agarose is suitable for binding most antibodies. However, Protein G Agarose has more affinity to bind mouse IgG than Protein A Agarose. A combined Protein A/G Agarose can be applied since this combination has the additive properties of Protein A and G Agarose.

To avoid nonspecific binding, appropriate controls are very important. Optimally, there should be a set of four different controls in ChIP PCR: positive control (RNA polymerase antibody), negative control (mouse IgG), “no antibody” control and an internal control (input). The control primers (GAPDH) and specific primers will be used to determine the outcome of ChIP-PCR (Table 2.).

Only IP DNA-produced positive binding at the specific location can be used for subsequent bisulfite analysis. For the negative binding samples, a regular bisulfite genomic sequencing can be used to determine DNA methylation status by which the ChIP assay is omitted.

As mentioned previously, IP DNA should be sheared to 200–1000 bp by sonication and subjected to the subsequent immnoprecipitation and purification procedures. The quality and quantity of IP DNA likely has been dramatically reduced during the ChIP treatment. For a limited amount of IP-DNA sample, several modifications can be applied to reduce further DNA damage and losS such as the use of low-melting-point agarose block during bisulfite reaction (23).

The basic principles for designing of methylation PCR primers and adjustments of PCR conditions have been well described previously (24, 25). However, ChIP-BMS uses DNA fragments (200–1000 bp) from IP DNA rather than genomic DNA to initiate bisulfite conversion. Different lengths of bisulfite primers covering the area of the IP DNA are necessary to determine the desired outcome of bisulfite PCR.

References

- 1.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16:6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kass SU, Pruss D, Wolffe AP. How does DNA methylation repress transcription? Trends Genet. 1997;13:444–449. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Methylation-induced repression belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell. 1999;99:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohlsson R, Renkawitz R, Lobanenkov V. CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet. 2001;17:520–527. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hark AT, Schoenherr CJ, Katz DJ, Ingram RS, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM. CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature. 2000;405:486–489. doi: 10.1038/35013106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikovits JA, Young HA, Vertino P, Issa JP, Pitha PM, Turcoski-Corrales S, Taub DD, Petrow CL, Baylin SB, Ruscetti FW. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upregulates DNA methyltransferase, resulting in de novo methylation of the gamma interferon (IFN-γ) promoter and subsequent downregulation of IFN-γ production. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5166–5177. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackwell TK, Kretzner L, Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN, Weintraub H. Sequence-specific DNA binding by the c-Myc protein. Science. 1990;250:1149–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.2251503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Höller M, Westin G, Jiricny J, Schaffner W. Sp1 transcription factor binds DNA and activates transcription even when the binding site is CpG methylated. Genes Dev. 1998;2:1127–1135. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.9.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohtani K, DeGregori J, Nevins JR. Regulation of the cyclin E gene by transcription factor E2F1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12146–12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Liu L, Andrews LG, Tollefsbol TO. Genistein depletes telomerase activity through cross-talk between genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:286–296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe AP. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature Genet. 1998;19:187–191. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vettese-Dadey M, Grant PA, Hebbes TR, Crane-Robinson C, Allis CD, Workman JL. Acetylation of histone H4 plays a primary role in enhancing transcription factor binding to nucleosomal DNA in vitro. EMBO J. 1996;15:2508–2518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DY, Hayes JJ, Pruss D, Wolffe AP. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell. 1993;72:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90051-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloy PL, Paul CL. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das PM, Ramachandran K, vanWert J, Singal R. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Biotechniques. 2004;37:961–969. doi: 10.2144/04376RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinmann AS, Farnham PJ. Identification of unknown target genes of human transcription factors using chromatin immunoprecipitation. Methods. 2002;26:37–47. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buck MJ, Lieb JD. ChIP-chip: considerations for the design, analysis, and application of genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments. Genomics. 2004;83:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orlando V, Strutt H, Paro R. Analysis of chromatin structure by in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking. Methods. 1997;11:205–214. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Neill LP, Turner BM. Immunoprecipitation of native chromatin: NChIP. Methods. 2003;31:76–82. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olek A, Oswald J, Walter J. A modified and improved method for bisulphite based cytosine methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:5064–5066. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li LC. Designing PCR primer for DNA methylation mapping. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;402:371–384. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-528-2_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li LC, Dahiya R. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1427–1431. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]