Abstract

Purpose

Dentate granule cell axon (mossy fiber) sprouting creates an aberrant positive-feedback circuit that might be epileptogenic. Presumably, mossy fiber sprouting is initiated by molecular signals, but it is unclear whether they are expressed transiently or persistently. If transient, there might be a critical period when short preventative treatments could permanently block mossy fiber sprouting. Alternatively, if signals persist, continuous treatment would be necessary. The present study tested whether temporary treatment with rapamycin has long-term effects on mossy fiber sprouting.

Methods

Mice were treated daily with 1.5 mg/kg rapamycin or vehicle (i.p.) beginning 24 h after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Mice were perfused for anatomical evaluation immediately after two months of treatment (“0 delay”) or after an additional 6 months without treatment (“6 mo delay”). One series of sections was Timm-stained, and an adjacent series was Nissl-stained. Stereological methods were used to measure the volume of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer and the Timm-positive fraction. Numbers of Nissl-stained hilar neurons were estimated using the optical fractionator method.

Key findings

At 0 delay, rapamycin-treated mice had significantly less black Timm staining in the granule cell layer plus molecular layer than vehicle-treated animals. However, by 6 mo delay, Timm staining had increased significantly in mice that had been treated with rapamycin. Percentages of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer that were Timm-positive were high and similar in 0 delay vehicle-treated, 6 mo delay vehicle-treated, and 6 mo delay rapamycin-treated mice. Extent of hilar neuron loss was similar among all groups that experienced status epilepticus and, therefore, was not a confounding factor. Compared to naïve controls, average volume of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer was larger in 0 delay vehicle-treated mice. The hypertrophy was partially suppressed in 0 delay rapamycin-treated mice. However, 6 mo delay vehicle- and 6 mo delay rapamycin-treated animals had similar average volumes of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer that were significantly larger than those of all other groups.

Significance

Status epilepticus-induced mossy fiber sprouting and dentate gyrus hypertrophy were suppressed by systemic treatment with rapamycin but resumed after treatment ceased. These findings suggest molecular signals that drive mossy fiber sprouting and dentate gyrus hypertrophy might persist for more than 2 months after status epilepticus in mice. Therefore, prolonged or continuous treatment might be required to permanently suppress mossy fiber sprouting.

Keywords: Timm stain, dentate gyrus, granule cell, hypertrophy, hilar neurons, rapamycin

Introduction

Granule cell axon (mossy fiber) sprouting is common in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (Sutula et al., 1989; de Lanerolle et al., 1989; Houser et al., 1990; Babb et al., 1991) and develops after epileptogenic injuries in animal models (Nadler et al., 1980; Lemos and Cavalheiro, 1995; Golarai et al., 2001; Santhakumar et al., 2001). Although underlying mechanisms are unclear (reviewed in Buckmaster, 2011), presumably, precipitating injuries trigger the expression of molecular cues that activate signaling pathways to coordinate mossy fiber growth and synaptogenesis. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the strength of triggering cues might peak shortly after injuries and then decline with time. If so, there might be a critical period when an effective treatment transiently administered might permanently prevent mossy fiber sprouting from ever developing. Critical periods for neuronal circuit formation occur during normal development (Hubel and Wiesel, 1970), and critical periods have been proposed for epileptogenic network reorganization following brain injuries (Graber and Prince, 2004; Giblin and Blumenfeld, 2011).

Recently, rapamycin, which inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway (reviewed in Swiech et al., 2008), was discovered to suppress mossy fiber sprouting (Buckmaster et al., 2009; Zeng et al., 2009), but it is unclear whether the effect lasts after treatment ends. Focal and continual infusion of rapamycin into the dentate gyrus for two months reduces mossy fiber sprouting after status epilepticus in rats, but by two months after rapamycin infusion ends mossy fiber sprouting returns to untreated levels (Buckmaster et al., 2009). In that study, however, only a small region of the dentate gyrus was infused, which raises the possibility that granule cells in neighboring uninfused areas retained the capacity to sprout mossy fibers after treatment ceased. To further test rapamycin’s long-term effect on mossy fiber sprouting in the present study, mice were treated systemically for two months after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus and perfused for mossy fiber sprouting immediately or after a six month delay.

Methods

Methods were described previously, and some of the mice in the control and 0 delay groups (see below) of the present study were included in a prior report (Buckmaster and Lew, 2011). Briefly, 46 ± 1 d old male and female mice of the FVB background strain were treated with pilocarpine (300 mg/kg, i.p.) ~50 min after atropine methylbromide (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Diazepam (10 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 2 h after the onset of stage 3 or greater seizures (Racine, 1972) and repeated if needed to suppress convulsions. During recovery, mice were kept warm and received lactated ringers with dextrose. Beginning 24 h after pilocarpine treatment, 1.5 mg/kg rapamycin or vehicle (5% Tween 80, 5% polyethylene glycol 400, and 4% ethanol) was administered (i.p.) daily for 2 months.

One set of mice was evaluated at the end of the 2 month treatment period (“0 delay”). The other set of mice was evaluated 6 months after rapamycin treatment ceased (“6 mo delay”), which was 8 months after status epilepticus. Mice were killed by urethane overdose (2 g/kg i.p.), perfused through the ascending aorta at 15 ml/min for 2 min with 0.9% sodium chloride, 5 min with 0.37% sodium sulfide, 1 min with 0.9% sodium chloride, and 30 min with 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4). Brains post-fixed overnight at 4°C. Then, one hippocampus was isolated, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PB, gently straightened, frozen, and sectioned transversely with a microtome set at 40 μm. Starting at a random point near the septal pole, a 1-in-12 series of sections from each hippocampus (average = 14 sections/mouse) was processed for Timm staining as described previously. An adjacent series was stained with 0.25% thionin.

During data analysis investigators were blind as to whether mice had been treated with vehicle versus rapamycin. From each Timm-stained section, an image of the dentate gyrus was obtained with a 10X objective using identical microscope (Axiophot, Zeiss) and camera (Axiocam, Zeiss) settings. NIH ImageJ (1.42q) was used to measure the total area of a contour drawn around the granule cell layer plus molecular layer and the threshold-detected subregion labeled black by Timm staining. Volumes were calculated by summing areas and multiplying by 12 (section sampling) and 40 μm (section thickness). For each hippocampus evaluated, percent of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer that was Timm-positive was calculated.

Numbers of Nissl-stained hilar neurons per hippocampus were estimated using Stereo Investigator (MBF Bioscience) and the optical fractionator method (West et al., 1991). The counting frame was 50 × 50 μm, and the counting grid was 75 × 75 μm. Using a 100X objective, nuclei were counted if they fell at least partially within the counting frame without touching upper or left borders, if they were not cut at the superficial surface of the section, and if the maximum diameter of their soma was ≥ 12 μm, which reduced the probability of including adult-generated ectopic granule cells. For total numbers of large Nissl-stained hilar neurons per dentate gyrus of all animals analyzed, the mean coefficient of error (0.09) was substantially less than the coefficient of variation (0.38), suggesting sufficient within-animal sampling.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat (Systat Software) with p < 0.05 considered significant. Values are expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

Results

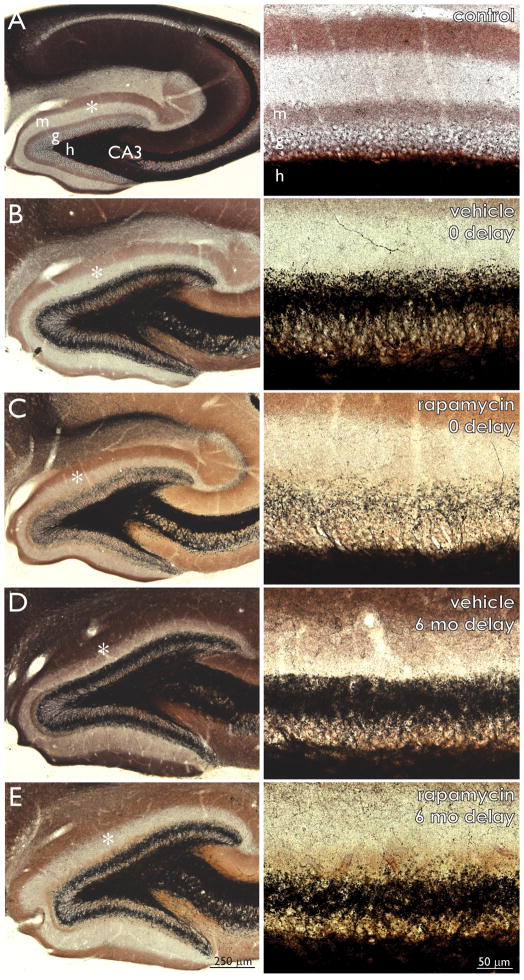

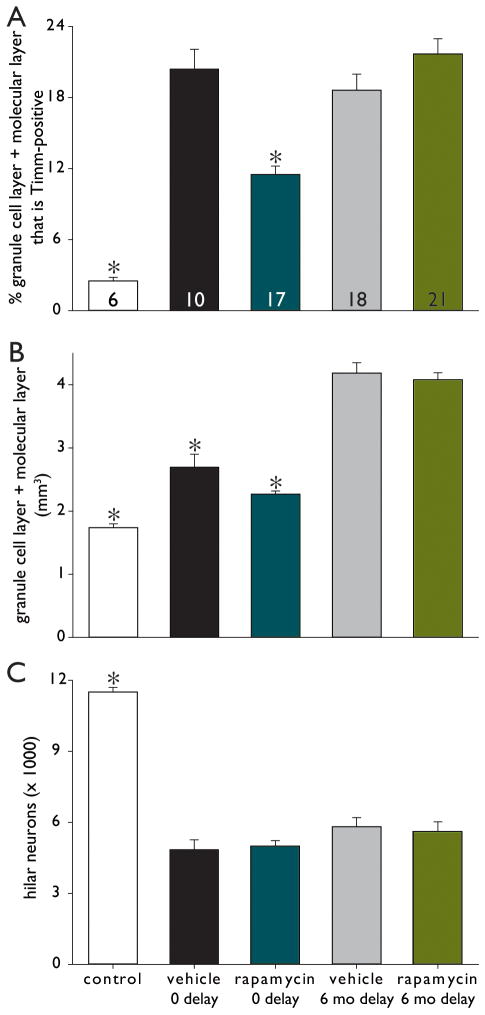

In naïve control mice (184 d old, 3 female, 3 male) there was very little black Timm staining in the granule cell layer and molecular layer (Figure 1A). Mice that had experienced status epilepticus, had been treated for 2 months with vehicle, and then had been immediately perfused (0 delay) displayed a dense band of black Timm staining in the inner molecular layer (Figure 1B). The level of aberrant Timm-staining appeared to be reduced in 0 delay rapamycin-treated mice (Figure 1C). At 6 mo delay, mice in both vehicle- and rapamycin-treated groups displayed a dense band of black Timm staining in the inner molecular layer (Figure 1DE). Timm-staining was quantified using stereological methods. Only 2.5 ± 0.3% (range = 1.3 – 3.5%, n = 6) of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer was Timm-positive in naïve control mice (Figure 2A). Compared to controls, black Timm staining in the granule cell layer plus molecular layer increased over 8-fold in 0 delay vehicle-treated mice (20.4 ± 1.7%, range = 10.0 – 28.3%, n = 10). Compared to 0 delay vehicle-treated mice, mossy fiber sprouting was reduced almost by half in 0 delay rapamycin-treated mice (11.5 ± 0.7%, range = 7.9 – 20.3%, n = 17). Vehicle- (n = 18) and rapamycin-treated mice (n = 21) had similar high levels of mossy fiber sprouting at 6 mo delay (18.6 ± 1.4%, range = 12.1 – 27.8% and 21.7 ± 1.3%, range = 11.9 – 31.4%, respectively). There were no significant differences in the average levels of mossy fiber sprouting in 0 delay vehicle-, 6 mo delay vehicle-, and 6 mo delay rapamycin-treated mice. Averages of the control and 0 delay rapamycin-treated groups were significantly different from one another and all other groups (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls method).

Figure 1.

Mossy fiber sprouting is suppressed by rapamycin but the effect does not persist after treatment stops. Timm-stained dentate gyrus of a naïve control mouse (A) and mice that experienced status epilepticus and were treated every day for 2 months with vehicle (B and D) or 1.5 mg/kg rapamycin (C and E) and then were perfused with no delay (B and C) or after a 6 month delay (D and E). Areas indicated by asterisks in left panels are shown at higher magnification in right panels. m = molecular layer, g = granule cell layer, h = hilus.

Figure 2.

Extent of mossy fiber sprouting (A), dentate gyrus volume (B), and number of hilar neurons per dentate gyrus (C) in naïve control mice and mice that experienced status epilepticus and were treated with vehicle or 1.5 mg/kg rapamycin every day for 2 months and then were perfused with no delay (0 delay) or after a 6 month delay (6 mo delay). Number of mice indicated in bars of panel A. *Different from all other groups, p < 0.05, ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls method.

After status epilepticus in mice the dentate gyrus hypertrophies, which is suppressed by rapamycin (Buckmaster and Lew, 2011). The dentate gyrus appeared larger in sections from mice after status epilepticus compared to naïve controls, and it appeared larger in 0 delay vehicle-treated mice compared to 0 delay rapamycin-treated mice (Figure 1A–C). The average volume of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer was 1.74 ± 0.06 mm3 in naïve control mice, 1.3-fold larger in 0 delay rapamycin-treated mice, and 1.6-fold larger in 0 delay vehicle-treated mice (Figure 2B). Dentate gyrus hypertrophy developed even further and to similar degrees in 6 mo delay vehicle- and 6 mo delay rapamycin-treated mice (Figure 1DE). Average volumes of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer in 6 mo delay vehicle- and 6 mo delay rapamycin-treated mice were over 2.3-fold that of naïve controls (Figure 2B). Averages of the control, 0 delay rapamycin-treated, and 0 delay vehicle-treated groups were significantly different from one another and all other groups (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls method).

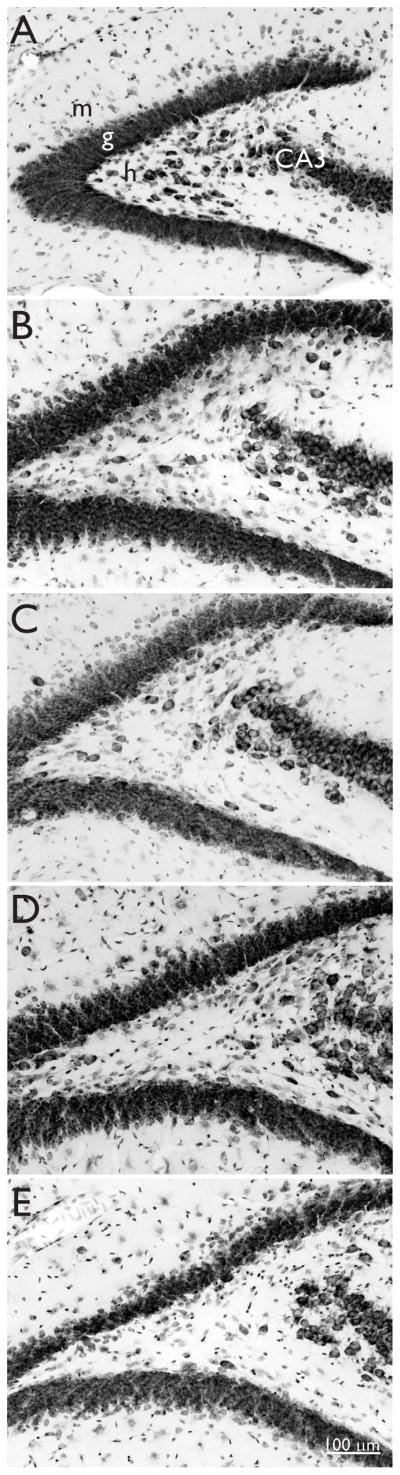

Naïve control mice had abundant, large, Nissl-stained hilar neurons (Figure 3A). Hilar neuron loss was evident in all groups that experienced status epilepticus (Figure 3B–E). The number of large hilar neurons per hippocampus in naïve control mice was 11,500 ± 200 (Figure 2C), which was more than all other groups (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls method). In groups that experienced status epilepticus, hilar neuron numbers were reduced to 42 – 51% of control values. There were no significant differences in the average numbers of hilar neurons in 0 delay vehicle-, 0 delay rapamycin-, 6 mo delay vehicle-, and 6 mo delay rapamycin-treated mice.

Figure 3.

Nissl staining reveals hilar neurons in a naïve control mouse (A) and hilar neuron loss in mice that experienced status epilepticus and were treated with vehicle (B and D) or 1.5 mg/kg rapamycin (C and E) every day for 2 months and then were perfused with no delay (B and C) or after a 6 month delay (D and E). m = molecular layer, g = granule cell layer, h = hilus, CA3 = CA3 pyramidal cell layer.

Discussion

Following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus, daily treatment with systemic rapamycin significantly reduced mossy fiber sprouting as reported previously. The principal finding of the present study was that 6 months after treatment ended the extent of mossy fiber sprouting had developed to untreated levels. This finding suggests signals that initiate and coordinate aberrant mossy fiber sprouting might persist for months after a precipitating injury and that treatments designed to block epilepsy-related synaptic reorganization may need to be protracted or continuous.

Results of the present study confirm previous reports that rapamycin suppresses mossy fiber sprouting when administration begins shortly after status epilepticus (Buckmaster et al., 2009; Zeng et al., 2009). In the present study it is likely that immediately after the 2 month treatment period, mossy fiber sprouting was suppressed in 6 mo delay rapamycin-treated animals as it was in 0 delay rapamycin-treated animals, because both groups were treated identically up to that point and sustained similar levels of hilar neuron loss when evaluated at the end of the experiment. Therefore, it is likely that initially suppressed mossy fiber sprouting developed to uninhibited levels after rapamycin treatment ceased in the 6 mo rapamycin-treatment group.

As reported previously, rapamycin suppresses hypertrophy of the dentate gyrus that develops after status epilepticus in mice (Buckmaster and Lew, 2011). Rapamycin and other mTOR inhibitors suppress neuronal hypertrophy in genetic mouse models in which the mTOR signaling pathway is overactive (Kwon et al., 2003; Meikle et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Ljundberg et al., 2009). However, similar to its waning effect on mossy fiber sprouting, rapamycin failed to permanently reduce dentate gyrus hypertrophy, and at 6 mo delay there was no significant difference in average volumes of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer in vehicle- and rapamycin-treated animals. In fact, results from those groups revealed that the dentate gyrus continued to enlarge after the two-month post-status epilepticus period. Dentate gyrus hypertrophy was not a confounding factor for evaluating mossy fiber sprouting, because black Timm-staining was measured as a percentage of the entire volume of the granule cell layer plus molecular layer, not an absolute value.

Together, the findings of delayed hypertrophy of the dentate gyrus and delayed development of mossy fiber sprouting after rapamycin treatment ended suggest that inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway shortly after an epileptogenic injury fails to permanently suppress epilepsy-related changes in dentate gyrus anatomy and circuitry. Thus, converging data do not support the hypothesis of a critical period to block dentate granule cell morphological abnormalities that develop after status epilepticus. In two experiments that used different species and different drug administration methods, initially suppressed mossy fiber sprouting developed to untreated levels after rapamycin treatment ended (present study; Buckmaster et al., 2009). These findings suggest that permanent inhibition of mossy fiber sprouting might require long-term treatment. To test that possibility it would be helpful to administer rapamycin longer than 2 months. However, rapamycin’s suppressive effect on mossy fiber sprouting appears to wane after 2 months (Buckmaster and Lew, 2011), suggesting other approaches will be necessary.

The cause/effect relationship between epileptogenesis and neuropathological abnormalities, including mossy fiber sprouting, in the dentate gyrus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy remains unclear. A primary motivation for testing rapamycin treatment is to determine whether or not mossy fiber sprouting is epileptogenic. Currently, reports are mixed. Zeng et al. (2009) used 6 mg/kg rapamycin every other day after kainate treatment in rats, which suppressed mossy fiber sprouting and seizure frequency. In contrast, we used 3 mg/kg rapamycin every day after pilocarpine treatment in mice, which suppressed mossy fiber sprouting but not seizure frequency. Huang et al. (2010) reported that 5 mg/kg rapamycin every other day rapidly reduced seizure frequency in chronically epileptic pilocarpine-treated rats, suggesting an anti-seizure effect, which could confound experiments that test anti-epileptogenesis. Perhaps mice require a higher dose of rapamycin than rats to reduce seizure frequency. Regardless of species differences, more work is needed to test whether or not inhibiting mTOR is anti-epileptogenic, and knowledge about rapamycin’s long-term effects on mossy fiber sprouting will be important for interpreting results.

The mTOR signaling pathway is activated in the hippocampus by epileptogenic treatments, including status epilepticus (Shacka et al., 2007; Buckmaster et al., 2009; Zeng et al., 2009) and traumatic brain injury (Chen et al., 2007). In pilocarpine-treated rats, increased mTOR activity persists into the chronic epilepsy stage (Huang et al., 2010; Okamoto et al., 2010). In the present study activation of the mTOR pathway was not measured, and molecular mechanisms underlying delayed mossy fiber sprouting remain unclear. One possibility is that a higher dose of rapamycin might have suppressed mossy fiber sprouting more permanently. Another possibility is that delayed mossy fiber sprouting was attributable to seizure activity that occurred during the 6 month period after rapamycin treatment ceased. Although the possibility cannot be excluded because mice were not seizure-monitored in the present study, it seems unlikely. While drug is administered, rapamycin- and vehicle-treated mice have spontaneous seizures that are similar in severity and frequency (Buckmaster and Lew, 2011), suggesting they probably had similar seizure activity after treatment stopped. If mice in the 6 mo delay rapamycin group were to experience more frequent or more severe seizure activity following treatment, one would expect that the extra seizure activity would have caused additional hilar neuron loss (Cavazos and Sutula, 1990). However, that was not the case. Finally, it is possible that status epilepticus caused long-lasting, perhaps epigenetic (Jessberger et al., 2007a), effects that resulted in persistent molecular triggers of mossy fiber sprouting.

In rodent models of temporal lobe epilepsy mossy fiber sprouting appears to plateau after 2–3 months (Okazaki et al., 1995). Different individuals display variable but presumably stable levels of mossy fiber sprouting, which ranged 2–3-fold among mice in each group of the present study. If signals triggering mossy fiber sprouting persist, why do levels of aberrant Timm staining not continue to increase? It probably is not attributable to an artifactual saturation effect of Timm staining, because the extent of mossy fiber sprouting measured with techniques similar to those used in the present study correlates with hilar neuron loss (Buckmaster and Dudek, 1997), suggesting a linear increase in sprouting as more hilar neurons, especially mossy cells, are killed during status epilepticus (Jiao and Nadler, 2007). Together, these findings suggest that after status epilepticus mossy fiber sprouting develops to a stable set-point that is not exceeded despite the possible persistence of triggering signals.

One might speculate that different individuals have different set-points, which are determined in part by the severity of precipitating injuries and perhaps also influenced by genetic factors. In other words, the level of mossy fiber sprouting might be controlled by currently unknown “homeostatic” feedback mechanisms. If so, this scenario suggests mossy fiber sprouting may be more dynamic than appears and raises the possibility of continual turnover. In fact, human epileptic tissue displays evidence of ongoing synaptic reorganization years after precipitating injuries (Isokawa et al., 1993; Mikkonen et al., 1998; Proper et al., 2000). Adult-generated granule cells extend mossy fibers into the molecular layer (Jessberger et al., 2007b; Kron et al., 2010), neurogenesis accelerates after seizure activity (Bengzon et al., 1997; Parent et al., 1997), and the generation of granule cells that sprout mossy fibers into the molecular layer might continue long after precipitating injuries, perhaps even indefinitely. Together, these findings suggest older granule cells with sprouted mossy fibers might be replaced by newer ones. If this were the case, there might be opportunities to reverse mossy fiber sprouting. Consistent with this hypothesis, grafts of CA3 pyramidal cells reduce mossy fiber sprouting even when implanted 45 days after kainate-treatment during which time considerable mossy fiber sprouting is likely to have developed (Shetty et al., 2005). In addition, mild mossy fiber sprouting generated by electroconvulsive shock was reported to decline over time (Vaidya et al., 1999). On the other hand, focal infusion of rapamycin for one month did not significantly reduce mossy fiber sprouting that already had developed for two months (Buckmaster et al., 2009), but perhaps longer and/or systemic treatment would be more effective. In fact, systemic rapamycin treatment beginning after spontaneous seizures had developed in epileptic pilocarpine-treated rats was reported to reduce mossy fiber sprouting (Huang et al., 2010).

In conclusion, the present study reveals that epilepsy-related changes in granule cell morphology can be suppressed but are resilient and develop fully after treatment ends. These findings argue against a critical period for mossy fiber sprouting, at least one less than two months long. These findings also raise questions about mechanisms underlying development and long-term maintenance of mossy fiber sprouting.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NINDS and NCRR of NIH.

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Footnotes

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Babb TL, Kupfer WR, Pretorius JK, Crandall PH, Levesque MF. Synaptic reorganization by mossy fibers in human epileptic fascia dentata. Neuroscience. 1991;42:351–363. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengzon J, Kokaia Z, Elmér E, Nanobashvili A, Kokaia M, Lindvall O. Apoptosis and proliferation of dentate gyrus neurons after single and intermittent limbic seizures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10432–10437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS. Mossy fiber sprouting in the dentate gyrus. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV, editors. Japser’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies. 4. Oxford UP; New York: 2011. in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Dudek FE. Neuron loss, granule cell axon reorganization, and functional changes in the dentate gyrus of epileptic kainate-treated rats. J Comp Neurol. 1997;385:385–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Ingram EA, Wen X. Inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway suppresses dentate granule cell axon sprouting in a rodent model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8259–8269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4179-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Lew FH. Rapamycin suppresses mossy fiber sprouting but not seizure frequency in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2337–2347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4852-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos JE, Sutula TP. Progressive neuronal loss induced by kindling: a possible mechanism for mossy fiber synaptic reorganization and hippocampal sclerosis. Brain Res. 1990;527:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91054-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Atkins CM, Liu CL, Alonso OF, Dietrich WD, Hu BR. Alterations in mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathways after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:939–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lanerolle NC, Kim JH, Robbins RJ, Spencer DD. Hippocampal interneuron loss and plasticity in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 1989;495:387–395. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giblin KA, Blumenfeld H. Is epilepsy a preventable disorder? New evidence from animal models. Neuroscientist. 2011;16:253–275. doi: 10.1177/1073858409354385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golarai G, Greenwood AC, Feeney DM, Connor JA. Physiological and structural evidence for hippocampal involvement in persistent seizure susceptibility after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8523–8537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber KD, Prince DA. A critical period for the prevention of posttraumatic neocortical hyperexcitability in rats. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:860–870. doi: 10.1002/ana.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR, Miyashiro JE, Swartz BE, Walsh GO, Rich JR, Delgado-Escueta AV. Altered patterns of dynorphin immunoreactivity suggest mossy fiber reorganization in human hippocampal epilepsy. J Neurosci. 1990;10:267–282. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00267.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Zhang H, Yang J, Wu J, McMahon J, Lin Y, Cao Z, Gruenthal M, Huang Y. Pharmacological inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway suppresses acquired epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J Physiol. 1970;206:419–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isokawa M, Levesque MF, Babb TL, Engel JE., Jr Single mossy fiber axonal systems of human dentate granule cells studied in hippocampal slices from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1511–1522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01511.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger S, Nakashima K, Clemenson GD, Jr, Mejia E, Mathews E, Ure K, Ogawa S, Sinton CM, Gage FH, Hsieh J. Epigenetic modulation of seizure-induced neurogenesis and cognitive decline. J Neurosci. 2007a;27:5967–5975. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0110-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger S, Zhao C, Toni N, Clemenson GD, Jr, Li Y, Gage FH. Seizure-associated, aberrant neurogenesis in adult rats characterized with retrovirus-mediated cell labeling. J Neurosci. 2007b;27:9400–9407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2002-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Nadler JV. Stereological analysis of GluR2-immunoreactive hilar neurons in the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy: correlation of cell loss with mossy fiber sprouting. Exp Neurol. 2007;205:569–582. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kron MM, Zhang H, Parent JM. The developmental stage of dentate granule cells dictates their contribution to seizure-induced plasticity. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2051–2059. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5655-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C-H, Zhu X, Zhang J, Baker SJ. mTor is required for hypertrophy of Pten-deficient neuronal soma in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12923–12928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132711100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos T, Cavalheiro EA. Suppression of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus and the late development of epilepsy in rats. Exp Brain Res. 1995;102:423–428. doi: 10.1007/BF00230647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungberg MC, Sunnen CN, Lugo JN, Anderson AE, D’Arcangelo G. Rapamycin suppresses seizures and neuronal hypertrophy in a mouse model of cortical dysplasia. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:389–398. doi: 10.1242/dmm.002386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle L, Talos DM, Onda H, Pollizzi K, Rotenberg A, Sahin M, Jensen FE, Kwiatkowski DJ. A mouse model of tuberous sclerosis: neuronal loss of Tsc1 causes dysplastic and ectopic neurons, reduced myelination, seizure activity, and limited survival. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5546–5558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5540-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkonen M, Soininen H, Kälviäinen R, Tapiola T, Ylinen A, Vapalahti M, Paljärvi L, Pitkänen A. Remodeling of neuronal circuitries in human temporal lobe epilepsy: increased expression of highly polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecular in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:923–934. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler JV, Perry BW, Cotman CW. Selective reinnervation of hippocampal area CA1 and the fascia dentata after destruction of CA3-CA4 afferents with kainic acid. Brain Res. 1980;182:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90825-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto OK, Janjoppi L, Bonone FM, Pansani AP, da Silva AV, Scorza FA, Cavalheiro EA. Whole transcriptome analysis of the hippocampus: toward a molecular portrait of epileptogenesis. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki MM, Evenson DA, Nadler JV. Hippocampal mossy fiber sprouting and synapse formation after status epilepticus in rats: visualization after retrograde transport of biocytin. J Comp Neurol. 1995;352:515–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.903520404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent JM, Yu TW, Leibowitz RT, Geschwind DH, Sloviter RS, Lowenstein DH. Dentate granule cell neurogenesis is increased by seizures and contributes to aberrant network reorganization in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3727–3738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03727.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proper EA, Oestreicher AB, Jansen GH, Veelen CWMv, van Rijen PC, Gispen WH, de Graan PNE. Immunohistochemical characterization of mossy fibre sprouting in the hippocampus of patients with pharmaco-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2000;123:19–30. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation: II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhakumar V, Ratzliff AD, Jeng J, Toth Z, Soltesz I. Long-term hyperexcitability in the hippocampus after experimental head trauma. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:708–717. doi: 10.1002/ana.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacka JJ, Lu J, Xie Z-L, Uchiyama Y, Roth KA, Zhang J. Kainic acid induces early and transient autophagic stress in mouse hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2007;414:57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty AK, Zaman V, Hattiangady B. Repair of the injured adult hippocampus through graft-mediated modulation of the plasticity of the dentate gyrus in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8391–8401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1538-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutula T, Cascino G, Cavazos J, Parada I, Ramirez L. Mossy fiber synaptic reorganization in the epileptic human temporal lobe. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:321–330. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiech L, Perycz M, Malik A, Jaworski J. Role of mTOR in physiology and pathology of the nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya VA, Siuciak JA, Du F, Duman RS. Hippocampal mossy fiber sprouting induced by chronic electroconvulsive seizures. Neuroscience. 1999;89:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJG. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in the subdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec. 1991;231:482–497. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092310411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng LH, Rensing NR, Wong M. The mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway mediates epileptogenesis in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6964–6972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0066-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L-H, Xu L, Gutmann DH, Wong M. Rapamycin prevents epilepsy in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:444–453. doi: 10.1002/ana.21331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]