Abstract

There are a number of factors that influence stigma in schizophrenia and it is important to understand them to successfully treat the illness. Gender-based stigma and how it is affected by culture is yet to be studied. This study explores gender issues from a socio-cultural perspective related to stigma among people in India suffering from schizophrenia. Stigma experiences were assessed by conducting individual interviews and the narratives were used as a qualitative measure. Men with schizophrenia reported being unmarried, hid their illness in job applications and from others, and experienced ridicule and shame. They reported that their experience of stigma was most acute at their places of employment. Women related their experiences of stigma to marriage, pregnancy and childbirth. Both men and women revealed certain cultural myths about their illnesses and how they affected their lives in a negative way. Information gathered from this study can be useful to understand the needs of individuals who suffer from schizophrenia to improve the quality of their treatment and plan culturally appropriate anti-discriminatory interventions.

Keywords: India, Schizophrenia, Stigma, Gender-based, Socio-cultural

Introduction

There are a number of factors that influence stigma in schizophrenia and it is important to understand them to successfully treat the illness. In India, where about 1.1 billion people reside, the prevalence of schizophrenia is about 3/1000 individuals (Gururaj, Girish, & Isaac, 2005). It is more common in men, and in terms of age of onset, men tend to be younger by an average of about five years than women when they develop schizophrenia. In terms of symptomatology, overall men with schizophrenia tend to have more negative symptoms, whereas women exhibit more affective symptoms (Leung & Chue, 2000). There are also differences in terms of prognosis; for example, women with schizophrenia tend to have better outcomes in terms of clinical course and occupational and social functioning compared to men (World Health Organization [WHO], 1973; Thara & Rajkumar, 1992).

Both men and women with schizophrenia experience stigmatization. In this context, stigma is defined as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” that reduces the bearer “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (Goffman, 1963, p.3). To successfully treat men and women who suffer from schizophrenia and associated stigma, it is also important to look at how their cultures may influence stigma. According to Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam, and Sartorius (2007) there is a paucity of research about cultural factors affecting stigma. Sartorius and Schulze (2005) have hypothesized that stigmatization could vary in different cultures. It could be possible that there exist different socio-cultural variants of stigmatization in developing countries that could influence the course and outcome of schizophrenia differently. Raguram, Raghu, Vounatsou, and Weiss (2004) used cultural epidemiology to describe how stigma is related to the cultural features of illness-related experience and behavior in people suffering from schizophrenia in Bangalore, India. In studying gender related to disability, specifically schizophrenia, Thara and Joseph (1995) found men to be disabled in occupational functioning and women in marital functioning (Shankar, Kamath, & Joseph, 1995; Thara & Srinivasan, 1997). The latter finding is expected, considering the social circumstances that are customary in India and also because in India, gender roles direct individuals along different life trajectories. On a background of cultural gender role expectations, Seeman (1983) proposed that families have higher educational and occupational expectations for their sons suffering from schizophrenia than towards daughters. These higher expectations could have differing ramifications on the course and outcome of the illness in men, compared to women. Also, due to the later age of onset of illness in women, parents of daughters with schizophrenia may tend to blame themselves less for their daughter’s illness, which usually appears after the daughters have left their parental home. On the contrary, due to the younger age of onset of schizophrenia in men, parents of sons with schizophrenia may tend to blame themselves for contributing towards their son’s illness (Seeman, 1983). Though these studies were significant in their findings, they did not specifically address gender perspectives on the stigma of schizophrenia within a socio-cultural framework. Thus, our focus was to look at the disadvantages created by stigma that exist among Indian men and women who have schizophrenia. By focusing on the cultural beliefs and barriers to help-seeking, it is hoped that improvements can be made in planning and executing culturally appropriate anti-discriminatory interventions.

Methodology

Sample

Of the 200 patients selected for the study, 100 of them lived in urban areas and visited the out-patient services of the six adult psychiatry units of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore, India. The remaining belonged to the rural areas, of which 51 attended the NIMHANS out-patient facility, and 49 sought the services of the six outreach centers located in the rural community (through the community services of the institute). By including participants from the rural environment of India, we attempted to cover the complete range of settings relevant to the study topic. Patients satisfying the criteria for schizophrenia, according to International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) were selected. Individuals asymptomatic for at least 6 months were chosen as symptoms could interfere with assessment. Patient’s case record, information from caregivers and a mental status examination by the treating psychiatrist were used for diagnostic confirmation. Further details of the methods have been described elsewhere in a study previously conducted by us (Loganathan & Murthy, 2008).

Instrument

A semi-structured instrument was used to assess stigma and discriminatory experiences. This was previously used in over a thousand patients and caregivers to assess stigma as a part of the Indian initiative of the World Psychiatric Association program to reduce stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia (Murthy, 2005). A factor analysis of this instrument was done and the final questionnaire was developed (Loganathan & Murthy, 2008). The questionnaire includes four open-ended questions asked during individual interviews that allowed the participants an opportunity to narrate their experiences and beliefs to the researcher (SL) in their own words: (1) Has your life changed after you have had the illness? (2) Are there things that you experience which others without the illness do not? (3) How do you cope with your illness? (4) Many people with similar illness experience shame, ridicule and discrimination? Have you also experienced any of these? The objective of this section was to provide room for the researcher to explore and probe topics that emerged. For example, “hiding their illnesses” was experienced by participants and was subsequently explored. Textual data of narratives were first transcribed verbatim and then translated to English by the researcher. Patients who spoke any of the three languages: Kannada, Tamil or English were chosen because the researcher was fluent in these languages (Tamil his first language). The researcher was also familiar with the culture of the participants.

Analyses

The narratives were read several times to understand any newly emerging themes. Thematic analysis of data was carried out using the framework approach (Pope, Ziebland, & Mays, 2000). For natural and objective analyses, the data was coded manually into constructs that clearly emphasized gender-based experiences in the Indian socio-cultural setting. These constructs were then modified according to the aims of the study, the topics raised by the participants and views that recurred in the data. The categories that emerged were: marriage and related myths, dilemmas associated with pregnancy and childbirth, and frustrations of securing a job and working. Charts were made for each domain and the various responses were listed. Both researchers looked at the coding until a consensus was reached.

Validity was improved by using triangulation as a way of comparing the qualitative data of the narratives with the findings derived from the instrument. This was performed to look for congruent patterns that would help in strengthening final interpretations. As necessary, the researcher’s cultural and ideological perspectives have been included in the discussion section as the interviews were conducted by him (Greenhalgh, 2006). Reliability was enhanced as data was analyzed not only by the researcher, but also by the co-author, (SMR) who is also familiar with the socio-cultural background of the participants.

Results

The sample consisted of 118 men and 82 women, with a total of 57% married and 31% never married. Of those who were never married, 24% were men and 7% were women. The constructs that emerged from the interviews were categorized as follows and the responses are listed accordingly.

Myths related to marriage

The responses (in narrative form below) describe the experiences that are associated with being diagnosed with schizophrenia and the prospects of marriage. The responses also point towards the public’s beliefs and myths about marriage, the barriers faced in getting married and the consequences faced within the family environment of the in-laws after entering a marriage. These consequences lead to concealment of illness to avoid further stigma and discrimination. Individuals are often advised by significant others not to get married at all, as this young man found out:

I used to go to college and study. Now I cannot because I am not the same sharp person I used to be. People tell me not to get married because of my illness.

In India, marriages taking place within the family, among relatives, are a common occurrence. These marriages are arranged by the elders of the family, sometimes even years before their children attain adult status. Even though family support is known to be a strong bonding factor in India, this individual shares his experience of being rejected by his own relatives after his marriage had been arranged with his cousin a few years ago:

I was to marry my cousin, now after my illness my relatives have decided not to get her married to me and have given her hand elsewhere. At home also people don’t give me importance, whatever I say has no value at all.

Various coping strategies are adopted to deal with the stigma of having schizophrenia. This man narrates his way of using concealment as a coping strategy from his own wife and in-laws for fear of being rejected. Often people substitute their mental illness with a medical illness which is more acceptable, such as having hypertension or headache or diabetes etc. Here is a description of a similar way of coping:

At the time of my marriage I had to hide that I have a mental illness. I myself do not tell my wife and my in laws that I have a mental illness. When people ask me “What is wrong with me,” I tell them that I have some sort of an allergy.

The consequences of illness being revealed to others can be disastrous for an individual. In this person’s case, he shares his feelings of abandonment by his wife and in-laws and how it lead to separation:

My wife and my in-laws used to call me mad and used to scold me when I had the illness. Later, they left me. I don’t tell anyone that I have a mental illness, fearing that I will not be respected or be looked down by him or her.

Though the above responses portray difficulty in getting married, myths exist about the illness resolving as a consequence of getting married. This young man shared his experience, and understood that marriage was not the solution to his illness. He stresses on the need for increasing awareness and decreasing myths among the population:

When people get to know that I have a mental illness, they tell me to get married and that I’ll get better. The best way to reduce the stigma is by educating the family members, especially the elders in the family.

Dilemmas faced during pregnancy and childbirth

The responses under this domain convey the series of experiences that a woman has to endure when she has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. She may experience discrimination as coercion not to have children, being forced to abort, separation from children and divorce. Having to endure abuse from a mother in-law recurs in this domain as well.

The need to bear a child among every Indian couple is critical for the survival of the marriage. In fact, it is a cultural belief that a woman should bear a child early during her married life. In this case a woman describes that even though she was pregnant; she was forced to get it aborted by her in-laws fearing that the offspring too will suffer from a similar fate. The genetic predisposition of schizophrenia is well established, but the generalizations and extreme reactions resorted to by the families can be addressed with adequate facts about the magnitude of the risks involved and the role of environmental factors, rather than holding on to myths that the offspring will suffer from schizophrenia:

My husband left me because I am mentally ill. When I was pregnant, my in-laws got an abortion done for me saying the children will also be mentally ill.

My relatives are not prepared to offer any girl within our family itself for my marriage as they feel the offspring may suffer. Many people approach me for marriage and then they don’t come back. Now I feel either I have to get married to a person with mental illness or to an elderly person as age is catching up with me.

Even if a woman begets a child, the possible consequences are that the child will be usurped by the in-laws, especially if it is a male child, and the woman is left to care for herself or she returns to her family. Here is one such instance where she faces ridiculing, abandonment and has to finally care for herself:

People call me all sorts of names and tease me as “mad” and “mental”. Even when I am fine they say things about me which unsettles me and I feel bad. My family has abandoned me. Now, I have to live all alone, away from my children.

In Indian culture the relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law is often a topic of debate in itself, as this relationship often decides if the atmosphere is cordial in the family. A decision taken by the mother-in-law sometimes influences others, including the patient’s husband. Here is an example of how a daughter-in-law was treated by her mother-in-law and her husband:

When I came to know that I have a mental illness I felt sad. My mother-in-law would come home and abuse me using filthy language. She said that I shouldn’t have children. Five months after that my husband divorced me.

Frustration in securing a job and working

Men were stigmatized mostly in relation to their occupations, both at their place of employment and if they were unable to become employed. This occurred more often than in the family arena, which is where most women experienced stigma. This young man describes that he lost the ability to work as well as he could have, and the consequent ridiculing that he faced:

I could work better before. Now, I can’t work continuously for more than three days. People would laugh and call me mad and I would get angry. Now, I don’t get angry.

Anyone having a government job is considered prestigious in India, and people react with envy when a person with mental illness has a government job. Rarely do employers support somebody who has a mental illness. Such examples should be used to educate other employers on the positive aspects of employing mentally ill persons. This woman relates positive experience on being able to work and has used spirituality as her way of coping with the illness:

I feel much better than during my illness. I believe a lot in GOD. Now, people are surprised and envy me and say this “madwoman” has a government job. I don’t care what they say and really don’t bother me. When people ask me what is or was wrong with me, I tell them about my experiences and leave the rest to their imagination. To reduce this stigma and discrimination I think only GOD can handle it. My boss at my workplace has been supportive and he himself has advised me not to tell anyone about this illness.

Holding a job after recovery from an illness like schizophrenia is a very important aspect of rehabilitation, as it encompasses a feeling of self-worth and maintains confidence. But the illness can dent communication and social skills. For example, a job in marketing may require additional social skills training, or placement that doesn’t test one’s social skills. Clinicians must pay attention to individual characteristics during their practice and suggest different options to such patients. This young man had problems with low self-esteem, which affected him at work:

People would avoid me, and I too avoid people due to poor rapport with them since my illness began. I feel I would not perform well. I feel I may need help in my job (marketing) and can’t deal with it on my own.

Others used concealment to protect themselves either from losing a job or getting a promotion, like this man who says:

I used to be assertive and spontaneous, now I don’t talk much and feel tired. I feel that I speak slowly, talk slowly, and don’t socialize much. I don’t tell about my illness to others because it may hamper my job or opportunity for promotion.

An unexpected discovery in the data was the respondents reporting physical abuse. Though the following narratives suggest some of the concerns voiced by the respondents, it is quite possible that many have experienced physical abuse and possibly sexual abuse, but may have found it uncomfortable in discussing with the researcher. There is a need to possibly use focus groups to discuss such sensitive issues, as it may foster a more acceptable forum, especially for women.

At home, my father resorts to beating me when he’s upset with me. He says I’m just acting ill. (Man)

I feel tired and cannot work like before. My husband and my brothers beat me. (Woman)

People call me “mad”. They see me and try to snatch away money from me. They don’t allow me to take part in any game with them. (Man)

People throw stones at me. They tease me and call me names. I used to be a tailor. Now, I cannot do that and work as a waiter in a hotel. My friends too throw coconut shells at me. (Man)

Discussion

On the whole, men in our study experienced shame and ridiculing, difficulties in getting married, hid their illness from others and job applications, and worried what others may think of them. In a previous study, stigma experienced by primary caregivers of people with schizophrenia, conducted by Thara and Srinivasan (2000), stigma was reported by the caregivers as high if the person suffering from the illness was female. This study measured the degree of stigma on a 4-point scale and compiled a stigma score. Our study differed in that we did not measure stigma, but analyzed patient’s direct views than caregiver’s opinion of stigma. We would like to emphasize from our study that both men and women experience stigma, and these experiences need to be viewed and understood from the primary roles assumed by them in the Indian socio-cultural setting.

Myths related to marriage

In Indian society, particularly the lower and middle socio-economic strata, men and women are assigned gender roles. For women, these roles are predominantly homemaker and child-bearer. Because of this, the prospective husband and his family may or may not be informed of the woman’s illness to protect these roles. This is a dilemma because there is a high chance that the prospective husband could withdraw the marriage proposal if informed, and there is a high risk of separation / divorce if the illness is kept a secret and discovered later. The latter situation is encountered in India when the patients’ illnesses relapse because they get married and discontinue their medications or do not have the finances to care for their illnesses (which have to be kept undisclosed). Married women are sometimes left to the mercy of their in-laws and husbands who invariably send them back to their families of origin forever. Sometimes they are left to wander in the streets for years before being brought to the hospital in an acutely psychotic, bizarre and shabby state. The ones who remain unmarried throughout their lives are taken care of by their parents. Often their parents have financial constraints and worry about who will care for their unmarried son/ daughter after their deaths (Thara, Kamath, & Kumar, 2003).

The narratives depict people advising patients not to get married, reports of unsuccessful marriage proposals, patients avoiding disclosure before marriage, and ridiculing and discrimination by one’s in-laws, all of these findings indicate that often, marriage is not favored for these individuals from others point of view. On the contrary, some patients are advised that marriage is a remedy for their illness and at times are coerced by significant others to get married. It has been shown that members of the general public are unable to recognize the illness as schizophrenia (Jorm, 2000). It may be that significant others view the illness as a ‘crisis’ or ‘emotional distress’ and are suggesting marriage as a socio-cultural remedy for a young, unmarried adult. Indeed, they may harbor the myth that the individual is in emotional distress (has developed the illness of schizophrenia) because they are unmarried. Therefore, education about the illness (and related marital issues for men and women) should begin early (preferably during the first contact with a care provider), especially among those who are young and unmarried. Even more importantly, a patient’s family must be educated; however, this is difficult due to the scarcity of psychiatrists in India. Thara et al., (2003) found that 50% of caregivers of women with schizophrenia felt dissatisfied with mental health service delivery, which may partly contribute to the lack of education about the illness.

In another study, Thara and Srinivasan (1997) point out that a relapsing/ continuous course of an illness has a detrimental effect on marriage. Our sample consisted of individuals who were asymptomatic for a minimum of six months, but still found difficulty in getting married. Various factors come into play once a person is diagnosed with schizophrenia, even if one is asymptomatic: the effects of labeling, social disadvantage and devaluation, lack of social skills or subtle negative symptoms (inattention, apathy), which can have a negative impact on one’s prospect of marriage. Sometimes these reasons can discourage other relatives’ likelihood of getting married (Raguram et al., 2004). The same explanation holds true for the fact that a majority of men in our sample were still single even though most were employed, which makes them otherwise eligible grooms. But when they do get married, their future depends on whether the spouse is supportive, which is usually the case. In India, among the lower and middle socio-economic strata, it is customary for the wife to live the rest of her married life with her husband’s family. Usually the woman is able to care for her husband’s illness, supervise his medication and ensure regular follow-up with care providers, otherwise the man is cared for by his parents.

Dilemmas faced during pregnancy and childbirth

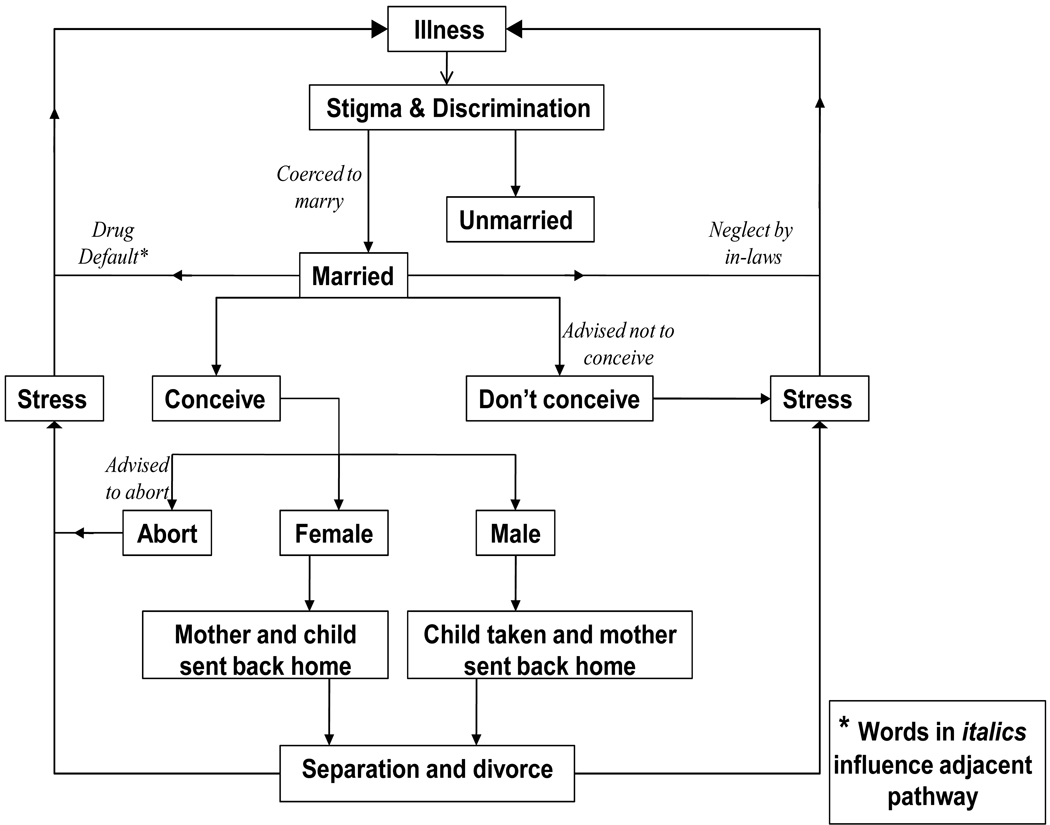

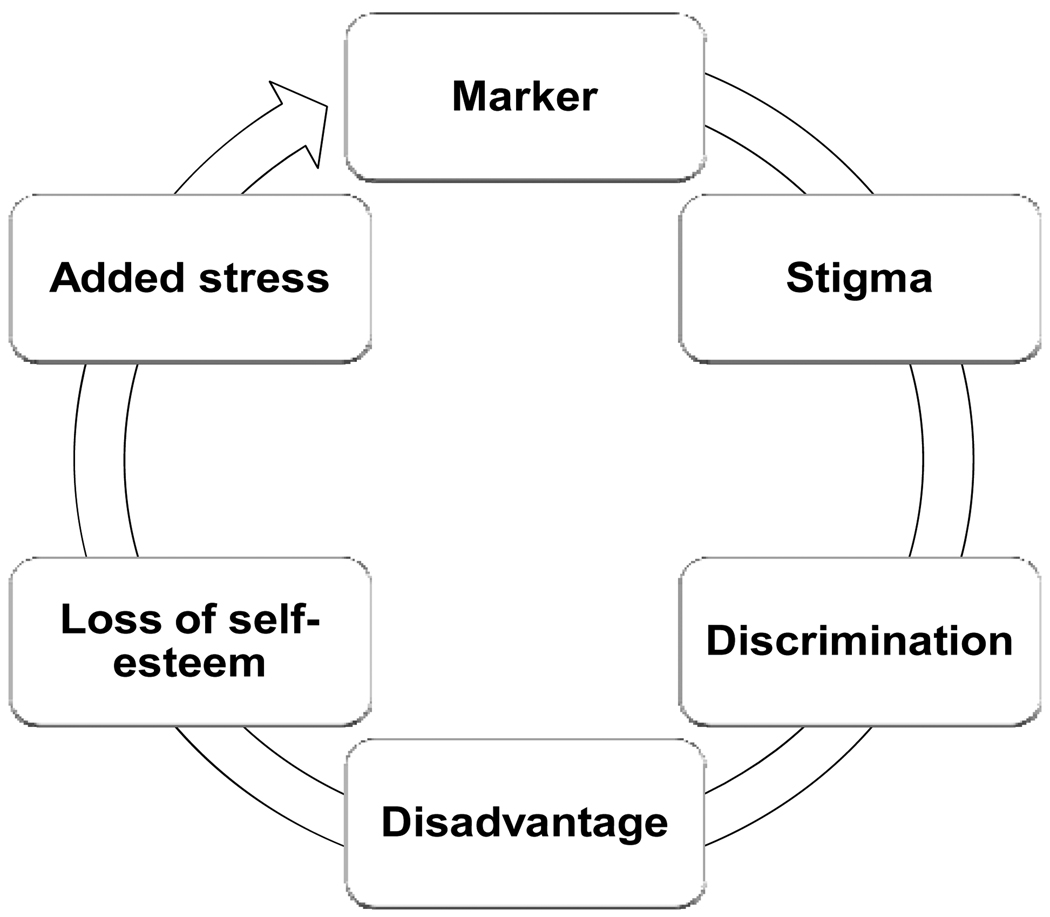

In India it is a cultural tradition that within a year or two, a married woman should give birth; otherwise she has to face a barrage of questions from her own family, relatives and society. If she doesn’t accomplish this role, the situation could be more stigmatizing than having schizophrenia. The sequence of miserable events and life experiences that a woman with schizophrenia is likely to experience throughout her child-bearing period is summarized in our model depicting the paths of influence in Figure 1. These events are similar to the conceptual model of the vicious cycle of stigmatization for an individual (figure 2) as outlined by Sartorius and Schulze (2005). As depicted in Figure 1, the role of the husband and in-laws in caring for the patient after her marriage is important for her future. In India, exploration of the mother-in-law’s attitude towards her mentally ill daughter-in-law can reveal interesting results. Figure 1 depicts the custody of the male child, which invariably is usurped by the in-laws. The girl child is often sent back with the mother to her parents’ home, thereby adding additional financial burden on these families (Thara et al., 2003). This pattern may differ from western cultures where custody loss means that most children (irrespective of gender) spend considerable time in foster homes. In anticipation of custody loss, pregnant women with schizophrenia in western cultures deny their pregnancy or refuse hospitalization postpartum leaving them vulnerable to complications (Miller, 1997). In developed countries, there is a need to empower such mothers with parenting skills, especially when a significant proportion of time is spent alone with their children (Test, Burke, & Wallisch, 1990). [Place Figure 1 and Figure 2 here].

Figure 1.

Pathways of stigma, discrimination and devaluation in young Indian women. (Comparable to the vicious cycle model)

Figure 2.

The vicious cycle model - a conceptual model

Modified with permission from Sartorius and Schulze (2005)

During a psychotic episode occurring in the post-partum, significant others may show sympathy, as entry of a newborn can overshadow the mother’s abnormal behavior. In some regions within India, abnormal behavior of a mother following childbirth is culturally accepted (known as “sanni”, “janni” in the state of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu respectively; and various other names in different states). Professionals too, make use of this cultural acceptance in ‘normalizing’ the behavior as far as possible, and control stigmatization to a certain extent. The impact of this cultural behavior on the course and outcome in women needs further detailed evaluation. It may be possible that it has a protective or favorable effect on the outcome as the woman gets all the attention and treatment, which may have been neglected otherwise. This reinforces the assumption by Sartorius and Schulze (2005) about different socio-cultural forms of stigmatization possibly influencing outcomes in developing countries. This form of cultural acceptance of abnormal behavior following childbirth provides an opportunity for involving the family in advice regarding education and care of the mother and child in terms of timing of breast feeding, medication timing, bonding and issues related to contraception. Miller (1997) have illustrated that counseling about family planning has been poorly addressed by mental health professionals. Contraceptive options too, are difficult to access, which perhaps reflects a type of stigmatization from the mental health service delivery system (Test et al., 1990).

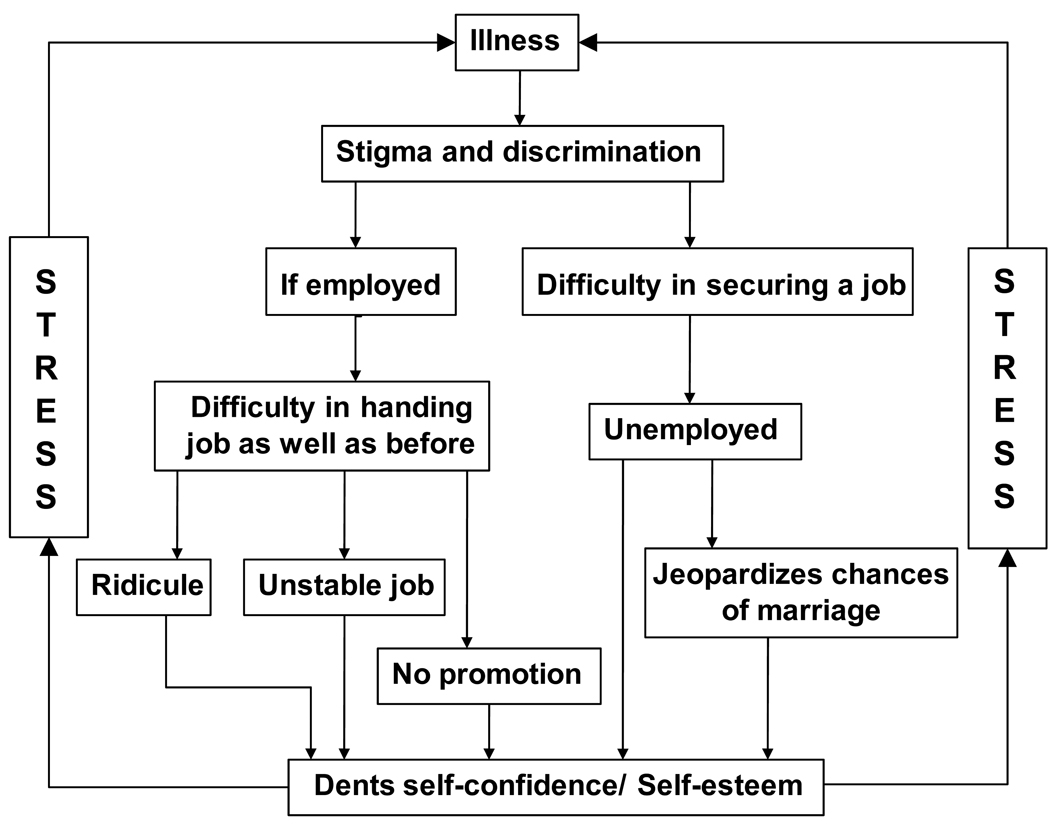

Frustration in seeking a job and working

In India, a key necessity for a man is to have a job as it symbolizes him as the primary bread winner of the family. It is most likely that fear of being rejected lead the men to avoid disclosures about their illnesses in job applications. Though the majority of the men in the study were employed, it indicates the intricacy involved in looking for a job among unemployed men. The same sample analyzed earlier (Loganathan & Murthy, 2008) emphasized the impact that the illness had on the self-esteem of individuals and their caregivers. In fact, most men worried what others would say if they disclosed their illnesses. Concealing illness may have been used as a coping strategy in order to secure a job, rent a house or get marriage proposals.

In some countries the government has stepped in to protect the rights and promote equal participation of the mentally ill in seeking jobs. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, enforced in the United States and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, in the United Kingdom includes and promotes the rights of people with mental disability to participate equally and attain employment without discrimination. In India, the People with Disability Act 1995, broadly mentions mental illness under the definition of disability, but job opportunities are reserved only for those with hearing impairment, blindness and locomotor disability, excluding mental illness. Though there is a lobby to amend the act by including mental illness, it has not gained momentum so far. Those unfortunate not to have jobs will continue to face stigmatization and remain disadvantaged as being unemployed. In India, employed patients, who are often hospitalized for short periods, claim a fitness certificate to get back to work. Though there are no guidelines to issue such certificates to prevent misuse, such a practice is probably prevalent in clinical practice to allow consumers to get back to work, which is of utmost importance to them. A study conducted in Hong Kong, Lee, Chiu, Tsang, Chui, and Kleinman (2002) showed that patients with schizophrenia requested doctors to conceal illness on sick notes compared to patients with diabetes. In India, too, consumers do request not to include mental illness in the draft (for fear of losing their job), but to substitute it with any other (medical) diagnosis. The problems arise when physicians refuse to issue such certificates and the consumers are left to manage on their own. The situation demands legislators to protect those remitted from a psychiatric condition to maintain their jobs, after being certified by a competent psychiatrist. This may not only protect the consumer, but also prevent misuse of certificates.

Among the employed, experiencing inability to work as productively as they used to before the illness began was common among respondents. As a consequence to this, patients were being ridiculed, feared losing their job and had concerns of being passed over for promotion. Staying unemployed can dent one’s self-esteem and self-confidence, and as we deciphered from the interviews can hamper the chances of getting married as well. The chain of events that men with schizophrenia face in their daily lives in the Indian socio-cultural setting are summed up our model depicting the paths of influence(Figure 3), that is comparable to the conceptual model by Sartorius and Schulze (Figure 2). Just as women would be blamed for not conceiving or not performing their family roles efficiently, men would be blamed in their inability to hold on to a stable job. In this regard, bringing about attitudinal change among the public is crucial if we want to encourage people with schizophrenia to stay employed and build their self-confidence. This calls for improving mental health literacy targeted at attitude change, displaying more tolerance and reducing high expectations of the employers and the public on people suffering from schizophrenia. Our model describing the life experiences of women (Figure 1) does not portray the complications that could impact women who also endorse work roles, and the model describing the lives of men (Figure 3) does not completely portray the trajectories that could complicate their marriage or chances of marrying. We have tried to depict the scenario that is commonly faced by majority of men and women living with schizophrenia in the Indian socio-cultural background. [Place Figure 3 here].

Figure 3.

Pathways of stigma, discrimination and devaluation in Indian men. (Comparable with the vicious cycle model- a conceptual model)

An important form of stigmatization that was serendipitously discovered through narratives was the violence associated with women. In previous studies, 51% to 97% of women diagnosed with schizophrenia reported physical or sexual abuse (Rice, 2008). This violence tends to remain invisible, since care providers as well as the criminal justice system turn down their appeal and refuse to accept it as true. As far as health care providers were concerned, they opined that violence was expected and took it for granted. Rice (2008) has brought forward this dissonance between women consumers and providers and calls for the nursing fraternity and mental health professionals to provide recovery- focused care so that these differing views can be made visible, with a possible solution to the outcome. Miller and Finnerty (1996) have highlighted many women with schizophrenia suffering violence during their pregnancies as well. Chernomas, Clarke, and Chisholm (2000) observed that women tend to remain silent and abstain from regularly attending counseling sessions in their society. However, through focus groups conducted during their study, the women were provided with an acceptable forum to discuss their concerns openly, and their published narratives illustrate their despair and hope (Chernomas et al., 2000). Thus, there is a need to assess sensitive themes like violence and sexual harassment in women where they relate and share their experiences with each other in an acceptable forum. Others studies have found higher rates of sexual harassment (Miller and Finnerty, 1996) and sexual coercion (Chandra, M. P. Carey, K. B. Carey, Shalinianant, & Thomas, 2003) in women with serious mental illness.

Conclusions

This study emphasizes the usefulness of qualitative research to understand the complexities of studying a concept such as stigma, which is further complicated by gender and socio-cultural influence. Though overall, men with schizophrenia reported not disclosing their illness to others, staying unmarried, experiencing shame/ridiculing, and worried what others think of themselves, we would like to stress that both men and women experience stigma, and the subjective experiences and the roles in which they are experienced are depicted and described in our study. Men tend to experience these in their work roles and women experienced them in their marital life, during pregnancy and child-birth. To this end, we used qualitative methods, in addition to the semi-structured instrument to look at gender perspectives of stigma in the social and cultural milieu of the heterogeneous Indian society, and it provided more evidence for further action and research. Discovery that post-partum psychosis has a culturally acceptable form (“sanni”, “janni”) in certain Indian cultures paves the way to explore its implications on the course and outcome of women sufferers of schizophrenia. It was also interesting to discover attitudes of mothers-in-law towards their mentally ill daughters-in-law in the Indian socio-cultural milieu. The model of the paths of influence proposed by us offer a socio-cultural perspective of the possible events in the lives of men and women sufferers of schizophrenia in India. From a clinical perspective, we believe that understanding and being aware of these various possibilities can greatly impact care provision for men and women with this illness in general, and management of psycho-social aspects, in particular. Our study supports the human rights attitude reiterated by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which is, to promote equal participation and inclusion in society of persons with disabilities. The latter term encompasses persons with mental illness and intellectual impairment.

Limitations

Interviewing patients who spoke either of the two South Indian languages was a limitation in discovering other potential variants of the culturally acceptable post-partum psychosis. The authors acknowledge that various forms may exist in other states and cultures as well. Follow-up of participants to assess or track their development in the range of constructs discussed was not possible. For example, how many of the unemployed finally got jobs? How many of the unmarried got married? Answers to these questions may have provided long-term measures of stigmatization among the participants. It would be debatable to include questions on violence and sexual harassment in stigma scales. They reflect as being important proxies for stigma, but may need sensitive probing.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Community Psychiatry wing of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) for assistance in data collection. Dr Santosh Loganathan was supported for his Post-doctoral Fellowship by Fogarty Grant # TW0581-08 (L.B. Cottler, PI). The authors especially thank Karen Dodson, Director and Managing Editor of Academic Publishing Services at Washington University School of Medicine, for her expert guidance and suggestions in shaping the final structure of the manuscript.

Biographies

PROF. SRINIVASA MURTHY, R., MD, is a retired Professor of Psychiatry, who has been involved with the Association for the Mentally Challenged (AMC), Bangalore, voluntary agency for mental handicap. Prof. Murthy has worked with World Health Organization (WHO) extensively. He was short term Consultant (STC) to assist in the development of national programmes of mental health in a number of developing countries from 1985–2003 (Bhutan, Iran, Kuwait, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Yemen). He functioned as Editor in Chief of the World Health Report 2001during 2000–2001. The report focused on Mental Health. Following retirement in 2004, he worked with the World Health Organization at the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Offices of Cairo and Amman. The last two years (2006–2007) of work was as mental health officer of WHO-Iraq. Research contributions have been mainly in the areas related to community mental health.

SANTOSH LOGANATHAN, MD, is a NIH-Fogarty International Center funded Post- Doctoral Research Fellow at Washington University School of Medicine, in St. Louis. His research interests include barriers to mental health care, stigma, using novel and cost-effective methods of mental health service delivery and studying the impact of culture on psychopathology and classificatory systems in psychiatry.

Address: Epidemiology and Prevention Research Group (EPRG), Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, 40 N Kingshighway, Suite 4, St. Louis, MO 63108 USA. [santoshl_28@yahoo.co.in]

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None

Funding source and conflicts of interest: The authors did not receive any funding for this study and report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Santosh Loganathan, Post Doctoral Research Fellow, Epidemiology and Prevention Research Group (EPRG), Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, 40 N Kingshighway, Suite 4, St. Louis, MO 63108 USA, Phone: 314-286-2272 (Work), Mobile: 314-556-4796, Fax: 314-286-2265, santoshl_28@yahoo.co.in.

Srinivasa Murthy, Professor of Psychiatry (Retired), Association for Mentally Challenged, C-301; CASA ANSAL Apartments, 18, Bannerghatta Road, J.P.Nagar, 3rd Phase, Bangalore, 560078 India. murthy_srinivasar@yahoo.co.in.

References

- Chandra PS, Carey MP, Carey KB, Shalinianant, Thomas T. Sexual coercion and abuse among women with a severe mental illness in India: An exploratory investigation. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00004-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomas WM, Clarke DE, Chisholm FA. Perspectives of women living with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:1517–1521. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper. BMJ Books: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Gururaj G, Girish N, Isaac MK. Mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders: Strategies towards a systems approach. New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; NCMH Background papers- Burden of disease in India. 2005

- Jorm AF. Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Chiu MYL, Tsang A, Chui H, Kleinman A. Stigmatizing experience and structural discrimination associated with the treatment of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;62:1685–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung A, Chue P. Sex differences in schizophrenia, a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;101:3–38. doi: 10.1111/j.0065-1591.2000.0ap25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loganathan S, Murthy RS. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;50(1):39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ. Sexuality, reproduction, and family planning in women with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1997;23:623–635. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ, Finnerty M. Sexuality, pregnancy and child rearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47:502–505. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.5.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy RS. Okasha A, Stefanis CN, editors. Perspectives on the Stigma of mental illness. World Psychiatric Association; Stigma of mental illness in the third world. 2005

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analyzing qualitative data. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raguram R, Raghu TM, Vounatsou P, Weiss MG. Schizophrenia and the cultural epidemiology of stigma in Bangalore, India. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:734–744. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000144692.24993.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E. The invisibility of violence against women diagnosed with schizophrenia. A synthesis of perspectives. ANS Advances in Nursing Science. 2008;31(2):E9–E21. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000319568.91631.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius N, Schulze H. Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman MV. Schizophrenic men and women require different treatment programs. Journal of Psychiatric Treatment and Evaluation. 1983;5:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar R, Kamath S, Joseph AA. Gender differences in disability: a comparison of married patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 1995;16:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00064-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Test MA, Burke SS, Wallisch LS. Gender differences of young adults with schizophrenic disorders in community care. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16(2):331–344. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thara R, Joseph AA. Gender differences in symptoms and course of schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;37(3):124–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thara R, Rajkumar S. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Results of a follow up study from India. Schizophrenia Research. 1992;7:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90075-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thara R, Srinivasan TN. Marriage and gender in schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;39(1):64–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thara R, Srinivasan TN. How stigmatising is schizophrenia in India? International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2000;46(2):135–141. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thara R, Kamath S, Kumar S. Women with schizophrenia and broken marriages-Doubly disadvantaged? Part II: Family Perspective. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2003;49:233–240. doi: 10.1177/00207640030493009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, Sartorus N. Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:192–193. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; The International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. 1973;Vol 1