The prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato DNA in diagnostic tissue samples from fresh cutaneous biopsies of 98 primary cutaneous lymphomas and 19 normal skin controls was investigated. A pathogenic role of B. burgdorferi in primary cutaneous B- and T-cell lymphomas from areas nonendemic for this microorganism is not supported nor is the consequent rationale for antibiotic therapy in these patients.

Keywords: Cutaneous lymphoma, Borrelia burgdorferi, hbb gene, Mycosis fungoides, MALT lymphoma, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of leg type, Infections

Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi has been variably associated with different forms of primary cutaneous lymphoma. Differences in prevalence rates among reported studies could be a result of geographic variability or heterogeneity in the molecular approaches that have been employed. In the present study, we investigated the prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato DNA in diagnostic tissue samples from fresh cutaneous biopsies of 98 primary cutaneous lymphomas and 19 normal skin controls. Three different polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocols targeting the hbb, flagellin, and Osp-A genes were used. Direct sequencing of both sense and antisense strands of purified PCR products confirmed the specificity of the amplified fragments. Sequence specificity was assessed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, and MultAlin software was used to investigate the heterogeneity of target gene sequences across the different samples.

Borrelia DNA was not detected in 19 controls, 23 cases of follicular lymphoma, 31 cases of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma, or 30 cases of mycosis fungoides. A single case of 14 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cases was positive for B. burgdorferi.

This study does not support a pathogenic role of B. burgdorferi in primary cutaneous B- and T-cell lymphomas from areas nonendemic for this microorganism and the consequent rationale for the adoption of antibiotic therapy in these patients.

Introduction

Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, infects its human targets when transmitted by the bite of Ixodes ticks, which are found mostly in certain endemic areas of North America and Central Europe. Different Borrelia strains have been variably associated with primary cutaneous lymphomas [1]. This association has been suggested by the correlation occurring between acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, a cutaneous manifestation of Lyme disease, and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas, and confirmed by serologic tests and molecular studies; these results are almost exclusively reported under the form of case studies or small retrospective series of primary and secondary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas [2–7]. B. burgdorferi DNA has been detected in 10%–42% of patients with cutaneous mucosa-associated lymphoma tissue (MALT) lymphomas, in 15%–26% of cases of cutaneous follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, and in 18% of mycosis fungoides diagnosed in some European countries [2, 3, 7, 8]. At variance with these figures, other American [9], European [10], and Asian [11] studies did not show these observations. Lyme disease can be successfully treated with Borrelia eradication with specific antibiotics, which is particularly evident for Borrelial lymphocytoma, a cutaneous manifestation of Lyme disease that is usually responsive to antibiotics [12]. These observations suggested that Borrelia infection should be investigated and, if present, eradicated in patients with cutaneous lymphomas. Nevertheless, only a few cases of cutaneous MALT lymphoma responding to antibiotics have been reported [1–4, 6, 7, 13–15]. Taken together, this incomplete evidence presently impairs our ability to show a definitive, significant association between B. burgdorferi and cutaneous lymphoma as well as the related rationale for the adoption of antibiotic therapy as an antilymphoma strategy. On these grounds, to overcome the limitations of small series and to perform a more comprehensive analysis with a molecular viewpoint, we extensively characterized a series of 98 consecutive cases of cutaneous B- and T-cell lymphoma of four different histotypes using three different Borrelia-specific PCR protocols.

Patients and Methods

Case Selection

Ninety-eight consecutive patients with a histopathological diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma of the B-cell or T-cell immunophenotype were included in the study. All cases were selected and independently reviewed by one expert dermatopathologist and at least two hematopathologists; cases with discordant diagnoses were discussed in a consensus meeting. Cases were classified as follicular lymphoma, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and mycosis fungoides according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer–World Health Organization classification [16]. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients, who were not treated with antibiotics, are summarized in Table 1. DNA collected from fresh-frozen skin biopsies was available for all cases analyzed. Histologically normal cutaneous specimens obtained during breast surgery from 19 consecutive surgical specimens were included as negative controls.

Table 1.

Clinical, histopathologic, and therapeutic features of the present series of 98 patients with cutaneous lymphomas

aInternational Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging system [24].

PCR Amplification

DNA from fresh-frozen skin biopsies was analyzed using three different PCR protocols. The first PCR protocol allowed the amplification of a 152-bp fragment of the hbb gene sequence for the detection of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, according to a previously published protocol [17]. The upstream forward primer displayed a sequence corresponding to a conserved region from nucleotide −16 to +19 (5′-GTAAGGAAATTAGTTTATGTCTTTT-3′) of the gene. The reverse primer showed a reverse sequence complementary to the hbb gene, spanning nucleotides 113–136 (5′-TAAGCTCTTCAAAAAAAGCATCTA-3′). PCR was performed in a 50-μL final mixture containing 500 ng DNA template, 5 μL 10X Fast Start Buffer containing 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), and 2.0 U of Fast Start Taq, and 10 pmol of each primer (all from Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The amplification program was carried out with a “hot-start” procedure using the following conditions: a first denaturation/activation step at 95°C for 3 minutes, a denaturation step at 95°C for 45 seconds, annealing at 50°C for 45 seconds, extension at 72°C for 45 seconds for 39 cycles, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes.

A second PCR protocol targeting the flagellin gene was also performed. The forward primer Fla1A spanning nucleotides 792–813 (5′-AGCAAATTTAGGTGCTTTCCA-3′) and the reverse primer spanning nucleotides 965–946 (5′-GCAATCATTGCCATTGCAGA-3′) were used to amplify a 174-bp fragment. PCR was performed in a 50-μL final mixture containing 500 ng DNA template, 5 μL AmpliTaq Gold Buffer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2.0 U Gold Taq (Applied Biosystems), and 10 pmol of each primer. Amplifications were carried out with a hot-start procedure using the following program: 94°C for 45 seconds, 60°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds for 44 cycles.

A third heminested PCR protocol targeting the Osp-A gene was performed as described [18], with only minor modifications.

Briefly, the first PCR was performed in a 50-μL final mixture containing 500 ng DNA template, 10 μL GoTaq Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2.0 U Go Taq (Promega), and 10 pmol of each primer (V1a, 5′-GGGAATAGGTCTAATATTAGC-3′; V1b, 5′-GGGGATAGGTCTAATATTAGC-3′; R1, 5′-CATAAATTCTCCTTATTTTAAAGC-3′; R37, 5′-CCTTATTTTAAAGCGGC-3′).

The amplification program was as follows: a first denaturation step at 95°C for 3 minutes, a denaturation step at 95°C for 45 seconds, annealing at 48°C for 45 seconds, extension at 72°C for 1 minute for 30 cycles, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes. For the second PCR round, 5 μL of the amplification product from the first PCR was added to the PCR mixture containing two different forward primers: V3a, 5′-GCCTTAATAGCATGTAAGC-3′; V3b, 5′-GCCTTAATAGCATGCAAGC-3′. The same conditions as outlined for the hbb PCR were used to obtain a 798-bp fragment.

In all PCR protocols, amplification of an 883-bp fragment of the glyceraldehyde gene was carried out as a control of DNA suitability.

All PCR products were analyzed using electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining, and DNA fragment size was quantified by image analysis (Image Station EDAS 290; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The specificity of the amplified fragments was confirmed using direct sequencing of both the sense and antisense strands of purified PCR products using an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence specificity was assessed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) and possible heterogeneity of the hbb, flagellin, and Osp-A sequences across the different samples was investigated using MultAlin software (http://multalin.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/).

Statistical Considerations

Comparison of Borrelia infection rates among different cutaneous lymphoma categories and in comparison with controls was conducted using χ2 or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. All probability values were two sided, with an overall significance level of 0.05. Analyses were carried out using the Statistica 4.0 statistical package for Windows (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK).

Results

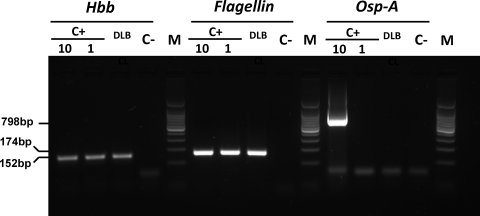

All lymphoma cases and controls were suitable for molecular analyses. After central pathology review, lymphoma categories were as follows: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, n = 14 (including five cases of “leg type” lymphoma); follicular lymphoma, n = 23; extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, n = 31; mycosis fungoides, n = 30. The prevalence of Borrelia DNA was investigated using three different PCR protocols in order to verify the presence of different regions of the bacterial genome in positive cases and to identify the genospecies involved. PCRs targeting the hbb and flagellin genes showed specific DNA sequences of B. burgdorferi in one lymphoma case (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the leg type) (Fig. 1), whereas all the other lymphoma categories and controls were negative (Fig. 2). PCR targeting of the Osp-A gene was negative in all cases assessed and in controls. The prevalence of B. burgdorferi DNA among diffuse large B-cell lymphomas was not statistically different from the prevalence in controls (7% versus 0%; p = .66).

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of the hbb gene fragment obtained from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was positive for Borrelia DNA. Sequences of reference strains of B. burgdorferi, B. afzelii, and B. garinii are shown for comparison.

Figure 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the detection of Borrelia DNA in the only cutaneous lymphoma (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) that scored positive in our series. Borrelia DNA was identified by two (hbb and flagellin) of three polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocols used. The sensitivities of the hbb and flagellin PCR protocols were comparable (DNA equivalent to 1 spirochete), whereas the Osp-A protocol had a lower sensitivity (DNA equivalent to 10 spirochete). C+, positive control, DNA equivalent to 1 and 10 spirochetes; C−, negative control; M, 100-bp ladder used as a marker.

Discussion

We herein report the largest available study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of Borrelia infection in patients with primary cutaneous lymphomas. According to our figures, the prevalence of Borrelia infection is extremely low within the most common forms of cutaneous lymphoma diagnosed in patients resident in northern Italy. The choice of three distinctive PCR protocols represented the most practical, best presently available comprehensive approach used to minimize the risk for false-negative results. In fact, in this study we employed robust, broadly used procedures for the detection of DNA from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, the main causative agent of Lyme disease in North America, and also DNA from B. azfelii and B. garinii, two strains prevalent in European countries [19]. The present data point toward a lack of association between cutaneous lymphoma and these infectious agents and, most importantly, preclude the use of antibiotic therapy in these malignancies. Accordingly, treatment against Borrelia infection should not be adopted outside areas endemic for this microorganism.

The main limitations of the present study are its retrospective nature, the lack of analysis extended to possible additional multifocal simultaneous lesions, and the unavailability of serological data in investigated patients. The presentation and behavior of cutaneous lymphomas are variable and sometimes represented by a history of simultaneous multifocal lesions that could be present both at diagnosis and at relapse. Importantly, all samples investigated herein were collected at diagnosis, whereby the DNA analyzed was from a single biopsy, regardless of the possible simultaneous presence of additional lesions; this potential bias, however, could be attenuated if we speculate that, once it is hypothesized that a local Borrelia infection could play a role in sustaining the growth of the lymphoma, we should expect the DNA from this bacterium to be detectable in any involved tissue. Unfortunately, serological data from the studied patients were not available and it is, therefore, not possible, once again theoretically, to exclude the possibility that a proportion of our lymphoma patients could actually have been infected by Borrelia despite the fact that this microorganism could not be detected in the lymphomatous biopsy at a molecular level; however, it is important to underline that, at least in the last 20 years, a good concordance rate between serology and PCR aimed to diagnose Borrelia infection does exist (Table 2). On the other hand, the above-mentioned limitations as well as patients' and disease characteristics present in our study are mostly overlapping with those described in previously reported studies. On these grounds, the possibility that Borrelia infection is associated with the most common forms of cutaneous lymphomas appears unlikely.

Table 2.

Case reports of cutaneous lymphomas treated with antibiotics

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FCL, follicular lymphoma; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; NA, not available; ND, not done; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; NR, no response.

Previously reported studies assessing the possible association between cutaneous lymphoma and infection by Borrelia strains at the molecular level are summarized in Table 3. All these studies but one investigated a single target gene using PCR and were invariably performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens. Studies performed in Japan, Taiwan, the U.S., Germany, and central Italy [10] excluded a Borrelia–lymphoma association, whereas two studies, mostly performed in areas endemic for some Borrelia genospecies and/or Lyme disease such as Austria and the Scottish Highlands, showed a prevalence of this infection in cutaneous lymphomas in the range of 18%–35% [2, 3]. The highest frequency was found in the MALT histotype (10%–42%), followed by follicular lymphoma (15%–20%) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (17%–33%). Moreover, Borrelia DNA was detected in 19% of 16 cases of primary cutaneous MALT lymphomas diagnosed in a nonendemic region of France [7]. These studies exhibited two major limitations: PCR amplicons were not sequenced to confirm Borrelia identity and the adopted PCR protocols were unable to discriminate among involved genospecies.

Table 3.

Molecular studies focused on the putative association between Borrelia infection and cutaneous lymphomas

Abbreviations: ATB, antibiotic therapy; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FCL, follicular lymphoma; Lp, lymphoplasmocytoid lymphoma; MF, mycosis fungoides; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; ND, not done; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

At variance with the literature, our study includes the largest series of cutaneous lymphoma ever tested so far for the presence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato DNA, in a comprehensive series analyzing the most frequent histologies. To further reduce methodological pitfalls, we exclusively used DNA extracted from fresh-frozen samples of diagnostic cutaneous biopsies and, for the first time, three different PCR protocols able to distinguish the major Borrelia genospecies. As a result of this rigorous approach, only one lymphoma contained B. burgdorferi DNA, thus suggesting that this association is markedly less frequent than hypothesized.

Another crucial and practical topic involves the importance of antibiotic therapy in lymphomas of the skin. Available data on treatment in our series clearly show that an antibiotic approach was not among our therapeutic choices (Table 1), but regression of cutaneous lymphoma after antibiotic therapy in a few anecdotal case reports represents a tempting argument, which corroborates a role for Borrelia in sustaining tumor growth (Table 2). Available evidence supporting this principle actually relies on only 11 cases: these patients were treated with a variable combination of antibiotics and often followed up for only a short period, with the intrinsic difficulty of drawing any conclusion about treatment efficacy. In fact, only half of the reported cases showed a tumor response; most importantly, because these cases were not reported within a clinical trial, it is likely that unsuccessfully treated cases were not reported, leading to activity overestimation. Along this line, antibiotic treatment should be indicated only in areas endemic for Borrelia infection, using regimens containing i.v. ceftriaxone or oral amoxicillin (Table 2).

Conclusion

The prevalence of Borrelia infection in tumor tissue is extremely rare in patients with cutaneous lymphoma diagnosed in areas nonendemic for this microorganism and/or Lyme disease. In these areas, Borrelia probably has no pathogenetic role in cutaneous lymphomas; accordingly, the search for it is expensive and has no clinical relevance, rendering antibiotic therapy useless. Conversely, in areas endemic for Borrelia infection, the use of antibiotics like ceftriaxone would constitute a rational choice to induce objective clinical responses in patients with these malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (to R.D., contract 10301). E.P. is a fellow of the Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro.

We thank Doctor Isabella Sassi for providing normal skin specimens from breast surgery.

Maurilio Ponzoni and Andrés J. M. Ferreri contributed equally to this work. Emilio Berti and Riccardo Dolcetti share senior authorship.

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Maurilio Ponzoni, Andrés J. M. Ferreri, Emilio Berti, Riccardo Dolcetti

Provision of study material or patients: Maurilio Ponzoni, Elisa Pasini, Silvia Govi, Fabio Facchetti, Daniele Fanoni, Claudio Doglioni, Alessandra Tucci

Collection and/or assembly of data: Maurilio Ponzoni, Andrés J. M. Ferreri, Silvia Mappa, Elisa Pasini, Silvia Govi, Arianna Vino, Claudio Doglioni, Emilio Berti, Riccardo Dolcetti

Data analysis and interpretation: Maurilio Ponzoni, Andrés J. M. Ferreri, Silvia Mappa, Elisa Pasini, Fabio Facchetti, Daniele Fanoni, Arianna Vino, Claudio Doglioni, Riccardo Dolcetti

Manuscript writing: Maurilio Ponzoni, Andrés J. M. Ferreri, Emilio Berti, Riccardo Dolcetti

Final approval of manuscript: Maurilio Ponzoni, Andrés J. M. Ferreri, Silvia Mappa, Elisa Pasini, Silvia Govi, Fabio Facchetti, Daniele Fanoni, Arianna Vino, Claudio Doglioni, Emilio Berti, Riccardo Dolcetti, Alessandra Tucci

References

- 1.Jelic S, Filipovic-Ljeskovic I. Positive serology for Lyme disease borrelias in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: A study in 22 patients; is it a fortuitous finding? Hematol Oncol. 1999;17:107–116. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1069(199909)17:3<107::aid-hon644>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodlad JR, Davidson MM, Hollowood K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and Borrelia burgdorferi infection in patients from the Highlands of Scotland. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1279–1285. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerroni L, Zöchling N, Pütz B, et al. Infection by Borrelia burgdorferi and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1997.tb01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garbe C, Stein H, Dienemann D, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated cutaneous B cell lymphoma: Clinical and immunohistologic characterization of four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:584–590. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70088-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goos M, Roelcke D, Schnyder UW. [Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans with fibrous nodules and monoclonal gammopathy] Arch Dermatol Forsch. 1971;241:122–133. In German. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kütting B, Bonsmann G, Metze D, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma: Complete clearing of skin lesions after antibiotic pulse therapy or intralesional injection of interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:311–314. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Fouchardiere A, Vandenesch F, Berger F. Borrelia-associated primary cutaneous MALT lymphoma in a nonendemic region. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:702–703. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200305000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tothova SM, Bonin S, Trevisan G, et al. Mycosis fungoides: Is it a Borrelia burgdorferi-associated disease? Br J Cancer. 2006;94:879–883. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood GS, Kamath NV, Guitart J, et al. Absence of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA in cutaneous B-cell lymphomas from the United States. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:502–507. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.281002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goteri G, Ranaldi R, Simonetti O, et al. Clinicopathological features of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas from an academic regional hospital in central Italy: No evidence of Borrelia burgdorferi association. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:2184–2188. doi: 10.1080/10428190701618250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li C, Inagaki H, Kuo TT, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: A molecular and clinicopathologic study of 24 Asian cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1061–1069. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picken RN, Strle F, Ruzic-Sabljic E, et al. Molecular subtyping of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates from five patients with solitary lymphocytoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:92–97. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonck CE, Viljanen M, Hirsimäki P, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma—a historical case. APMIS. 1998;106:947–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grange F, Wechsler J, Guillaume JC, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated lymphocytoma cutis simulating a primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:530–534. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roggero E, Zucca E, Mainetti C, et al. Eradication of Borrelia burgdorferi infection in primary marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the skin. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:263–268. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Fourth Edition. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008. pp. 1–439. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Portnoi D, Sertour N, Ferquel E, et al. A single-run, real-time PCR for detection and identification of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species, based on the hbb gene sequence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;259:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michel H, Wilske B, Hettche G, et al. An ospA-polymerase chain reaction/restriction fragment length polymorphism-based method for sensitive detection and reliable differentiation of all European Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species and OspA types. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2004;193:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s00430-003-0196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takino H, Li C, Hu S, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: A molecular and clinicopathological study of cases from Asia, Germany, and the United States. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1517–1526. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosa PA, Hogan D, Schwan TG. Polymerase chain reaction analyses identify two distinct classes of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:524–532. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.524-532.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman JL, Jurkovich P, Kramber JM, et al. Molecular detection of persistent Borrelia burgdorferi in the urine of patients with active Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1991;59:269–278. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.269-278.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aberer E, Fingerle V, Wutte N, et al. Within European margins. Lancet. 2011;377:178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: A proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Blood. 2007;110:1713–1722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-055749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]