Abstract

Heart-failure phenotypes include pulmonary and systemic venous congestion. Traditional heart-failure classification systems include the Forrester hemodynamic subsets, which use 2 indices: pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and cardiac index. We hypothesized that changes in PCWP and central venous pressure (CVP), and in the phenotypes of heart failure, might be better evaluated by cardiovascular modeling. Therefore, we developed a lumped-parameter cardiovascular model and analyzed forms of heart failure in which the right and left ventricles failed disproportionately (discordant ventricular failure) versus equally (concordant failure). At least 10 modeling analyses were carried out to the equilibrium state. Acute discordant pump failure was characterized by a “passive” volume movement, with fluid accumulation and pressure elevation in the circuit upstream of the failed pump. In biventricular failure, less volume was mobilized. These findings negate the prevalent teaching that pulmonary congestion in left ventricular failure results primarily from the “backing up” of elevated left ventricular filling pressure. They also reveal a limitation of the Forrester classification: that PCWP and cardiac index are not independent indices of circulation.

Herein, we propose a system for classifying heart-failure phenotypes on the basis of discordant or concordant heart failure. A surrogate marker, PCWP–CVP separation, in a simplified situation without complex valvular or pulmonary disease, shows that discordant left and right ventricular failures are characterized by differences of ≥4 and ≤0 mmHg, respectively. We validated the proposed model and classification system by using published data on patients with acute and chronic heart failure.

Key words: Blood volume; cardiac output; cardiovascular physiological phenomena; central venous pressure; heart failure/classification/physiopathology; heart ventricles/physiopathology; hemodynamics/physiology; models, cardiovascular; myocardial infarction/physiopathology; pulmonary wedge pressure/physiology; vascular resistance/physiology; ventricular function

It is well recognized that left ventricular (LV) failure results in pulmonary venous congestion, whereas right ventricular (RV) failure results in systemic venous congestion.1 What is not well understood is the underlying physiologic mechanism.2,3 The traditional concept of this process is that LV failure causes elevated LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), which affects the left atrial pressure (LAP); in turn, the LAP is transmitted into the pulmonary venous pressure, causing pulmonary congestion.4 A comparable concept is applied to RV failure. This process may be called the “back-up pressure” mechanism. In addition, LV failure may further transmit the pressure load into the pulmonary circulation, eventually leading to RV dysfunction or failure.

The use of cardiac hemodynamic monitoring in heart-failure management originated with right-sided heart catheterization—described by Cournand and colleagues5 in 1945—and was later facilitated by the pulmonary artery balloon flotation catheter.6 In 1971, Forrester and colleagues7 described differences in the central venous pressure (CVP) and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) in 50 patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The PCWP correlated with the presence or absence of pulmonary congestion, but the CVP did not; an optimal cardiac output was associated with a PCWP of 15 mmHg,8 which suggested that hemodynamic intervention was feasible. As a result of these discoveries, the emphasis shifted to left-sided cardiac hemodynamics in the evaluation of heart failure. In 1976, after studying 200 patients, Forrester and associates described a hemodynamic-subsets classification system9 for determining a patient's hemodynamic status (H) by using the PCWP and cardiac index (CI). This system comprises 4 categories, each defined in relationship to a CI of 2.2 L/min/m2 and a PCWP of 18 mmHg: H-I, CI >2.2 and PCWP <18 mmHg; H-II, CI >2.2 and PCWP >18 mmHg; H-III, CI <2.2 and PCWP <18 mmHg; H-IV, CI <2.2 and PCWP >18 mmHg. The Forrester classification remains a cornerstone in the targeted treatment of acute heart failure.10,11

Earlier, in an experimental model, Lindsey and co-authors12 had shown that blood volume was redistributed into the pulmonary circulation in LV failure. This observation prompted Guyton13 to devise a graphical representation of compartmental blood flow between the systemic and pulmonary beds. This representation considered the venous return curve and the role of right atrial pressure (RAP) in controlling venous return and cardiac output. Guyton revived the important concept of the mean circulatory filling pressure,14–17 which is the mean vascular pressure at which there is no pump function and the pressures in the arterial and venous beds are instantaneously equilibrated. The mean circulatory filling pressure can be estimated experimentally and is also a measure of vascular tone and stressed vascular volume, which is the pressure-generating volume present in the vasculature, aside from the unstressed volume (which is approximately 70% of the total blood volume [TBV]).18 In Guyton's analysis, the blood volume in the systemic bed (SBV) is represented by the mean systemic pressure (Pms), and the blood volume in the pulmonary bed (PBV) is represented by the mean pulmonary pressure (Pmp). In isolated LV failure, the PBV and Pmp are increased, whereas the SBV and Pms are decreased. Conversely, in isolated RV failure, the SBV and Pms are increased, but the PBV and Pmp are decreased.12,13

Clinically, PBV has been measured by using indicator dilution techniques and radiocardiography. In diverse cardiovascular diseases, researchers have related PBV to the TBV and LAP,19 although they have not recognized that this correlation indicates any relationship between PBV and cardiac contractile function. Forrester's classification system does not take into account the role of PBV and RV function, nor does it encompass a possible role for CVP as an independent index for circulatory evaluation.

We have developed a computerized cardiovascular model for analyzing hemodynamic characteristics and volume movement in simulated acute heart failure. In this report, we show that by simultaneously integrating LV with RV function, this model provides a better understanding of how PCWP and CVP interact in heart failure. We also propose a physiologic heart-failure classification system on the basis of our findings. We validated the proposed model and classification system by using published clinical data. Accordingly, these findings have important implications in the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure.

Materials and Methods

The study consisted of 2 parts. First, mathematical modeling of the cardiovascular circuit was performed to analyze volume movement in heart failure. Second, the proposed mathematical model of heart failure was validated by analyzing published series of patients, including 1 study of patients with chronic cardiovascular disease19 and 3 studies of patients with AMI.20–22

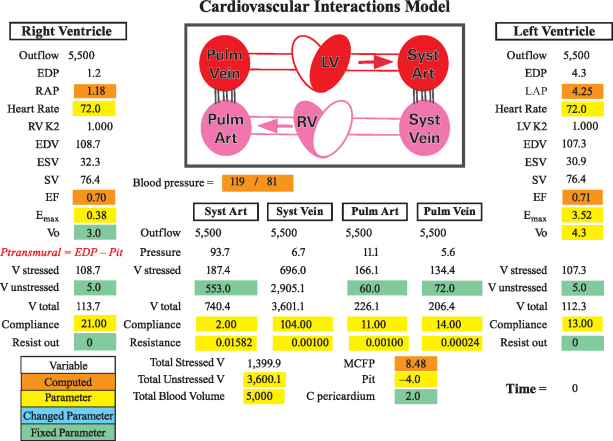

We used Cardiovascular Interactions (CVI), a software program created by one of us (CFR) for modeling cardiovascular interactions.23 An updated version of this mathematical model consists of 6 elements (2 ventricles, 2 arterial beds, and 2 venous beds) (Fig. 1).24 The heart pump is modeled with an elastance function—termed time-varying ventricular elastance—which represents pressure change over volume change as a function of time.25 The maximum time-varying ventricular elastance (Emax)26–28 is separately configured for the LV (LV-Emax) and the RV (RV-Emax). The atria are not directly modeled. The left and right atrial pressures (LAP and RAP) are calculated by subtracting the decrease in pressure (flow × resistance) from the upstream pressure. The cardiovascular model is founded upon principles of hydraulic circuits and the conservation of (blood) mass. In this formulation, pressure drops as blood flows across a conduit with a finite resistance. Because we knew the mean pressure in the proximal arterial bed (which is generated by the LV elastance function) and the arterial-bed resistance parameter (which is based on the general consensus of the parameter value in the medical literature), we could calculate the proximal systemic venous bed pressure (Fig. 1). Next, because we knew the venous-bed resistance parameter, we could calculate the downstream RAP without necessarily modeling the atrium itself. The same condition applied when determining the LAP. This approach was valid in that we were primarily concerned with the mean pressures and flow changes, rather than phasic changes, in this analysis.

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of the Cardiovascular Interactions model (available from crothe@iupui.edu or http://www.apsarchive.org/resource.cfm?submissionID=997). This model contains 6 elements (2 ventricles, 2 arterial beds, and 2 venous beds) and computes directional flows from the systemic (syst) vein through the right ventricle (RV), pulmonary vein, left ventricle (LV), and systemic artery and vein. The ventricular end-diastolic pressure (EDP) is computed as ventricular volume/compliance, the volume (V) being represented by the latest volume plus inflow minus outflow. The left and right atrial pressures are calculated by subtracting the pressure reduction (flow × resistance) from the upstream pressure. The model-defined parameters are shaded in green and the variable parameters in yellow. Variable parameters that have changed from their initial values are displayed in blue (blue value not shown in the diagram with default parameters only). The computed variables are shaded in orange.

Art = artery; C = compliance; EDV = end-diastolic volume; EF = ejection fraction; Emax = maximal elastance; ESV = end-systolic volume; K2 = conductance factor that becomes less than 1.000 at high heart rates (simulates the reduced filling at high heart rates); LAP = left atrial pressure; MCFP = mean circulatory filling pressure; Pit = thoracic pressure; Pstress = stressed pressure; Ptransmural = transmural pressure (EDP – Pit); Pulm = pulmonary; RAP = right atrial pressure; SV = stroke volume; Vo = ESV at a zero-generated pressure

In applying the CVI program, we used the extent of LV and RV contractile-function mismatch (the ratio of the percentage maximum of LV-Emax to the percentage maximum of RV-Emax) as the LV/RV contractile-function index. We defined an index of 1 as concordant biventricular failure, an index of <1 as discordant LV failure, and an index of >1 as discordant RV failure.

In accordance with Guyton's approach to calculating pulmonary circulatory volume,12 where the LV diastolic volume is included in the functional pulmonary bed, we used the CVI model to evaluate the LAP and stressed pulmonary-bed plus LV-volume (pulm + LV) changes in different heart-failure configurations. Similarly, we used the CVI model to evaluate the RAP and stressed systemic-bed plus RV-volume (syst + RV) changes in different heart-failure configurations. In addition, we simulated hypervolemia by increasing the TBV to 5,500 cc. This degree of acute volume change (+10%) is less than that in Guyton's experiment (+200 cc in 14-kg dogs),29 and it is considerably less than the acute clinical removal of 2,000 cc of fluid in heart-failure patients by means of ultrafiltration.30

To simulate discordant LV failure, we either decreased LV-Emax or concurrently decreased LV-Emax and RV-Emax (where LV-Emax was decreased by a greater degree than was RV-Emax). We used a similar approach to simulate discordant RV failure. Biventricular failure was simulated by simultaneously decreasing LV-Emax and RV-Emax by the same degree. For each type of heart failure, at least 10 simulations were carried out to the equilibrium state. In this analysis, we defined pulmonary (venous) congestion as an expansion of pulmonary (pulm + LV) blood volume and LAP elevation, and we defined hepatic or systemic (venous) congestion as an expansion of systemic (syst + RV) blood volume and RAP elevation.

We next used published clinical data to validate the resulting model and our new system of heart-failure classification. To validate the concept that PBV expansion and LAP elevation are intimately related and to determine whether they are consequent to (that is, dependent changes of) LV dysfunction, we tested these 2 variables in data from 2 series of patients (total n=69) who had been studied by Lewis and associates.19 These patients had diverse cardiovascular disorders and underwent simultaneous measurement of PBV and LAP. Their cardiac output had also been measured. To validate the use of PCWP–CVP separation in differentiating between LV and RV failure, we examined 3 separate studies20–22 in which the RAP and LAP were simultaneously measured in patients who had acute LV or RV infarction.

Results

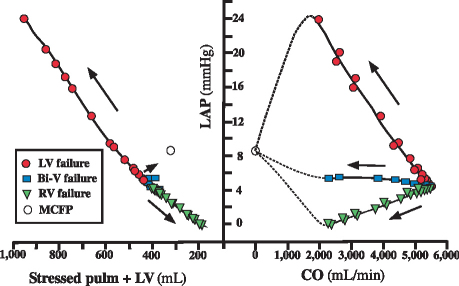

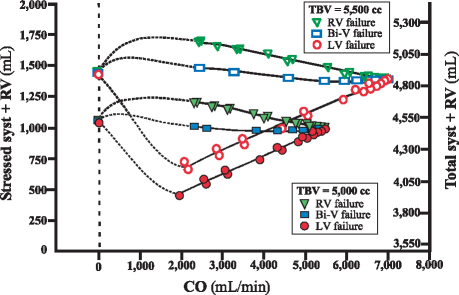

In the mathematical model, to compare the LAP changes observed in RV, LV, and biventricular failure, we plotted the equilibrium level of cardiac output for each type of heart failure (Fig. 2, right panel). The CVI program showed that at any given level of cardiac output, the LAP is highest in LV failure, lower in biventricular failure, and lowest in RV failure. At each level of LAP, we observed a corresponding level of PBV. As shown in Figure 2 (left panel), the elevated LAP observed in LV failure was associated with an increased stressed pulm + LV volume, which signals a shift of volume out of the systemic circulation as cardiac output decreases. However, fluid migration to the pulmonary circuit was minimal in biventricular failure and migrated in the reverse direction in RV failure. The right-sided hemodynamic values (Fig. 3) showed that RV failure caused fluid migration to the systemic bed (syst + RV). Hypervolemia dramatically shifted the volume–cardiac output curves rightward and upward (Fig. 3, upper group of curves), resulting in greater systemic congestion. These results reflect greater compliance and capacitance of the systemic vascular (venous) bed than of the pulmonary vascular (venous) bed.

Fig. 2 Pulmonary volume and left atrial pressure (LAP) in different modes of heart failure. Right: The relationship between the LAP and the equilibrium cardiac output (CO). The pressure at zero CO is equilibrated to the mean circulatory filling pressure (MCFP). The thoracic pressure is set at −4 mmHg. Simulations with a CO of <2 L/min were not used. Dotted lines show extrapolations. Left: The LAP is plotted as a function of stressed pulmonary (pulm) plus left ventricular (LV) volume in different heart-failure modes. The arrows show the direction of decreasing CO. The LAP and stressed pulm + LV volume increase in LV failure, decrease in right ventricular (RV) failure, and are almost unchanged in biventricular (Bi-V) failure.

Fig. 3 Systemic blood volume in left ventricular (LV), right ventricular (RV), and biventricular (Bi-V) heart failure. Symbols at bottom: Relationship between the stressed systemic volume (syst + RV) and the equilibrium cardiac output (CO). The total systemic volume (total syst + RV) is also shown. Dotted lines show extrapolations. Symbols at top: Effect of hypervolemia (total blood volume [TBV] = 5,500 cc), or a 10% increase from baseline. The difference in compliance between the pulmonary and systemic beds causes most of the added volume to be in the systemic bed. Consequently, discordant LV failure in hypervolemia causes a greater amount of volume mobilization into the pulmonary bed.

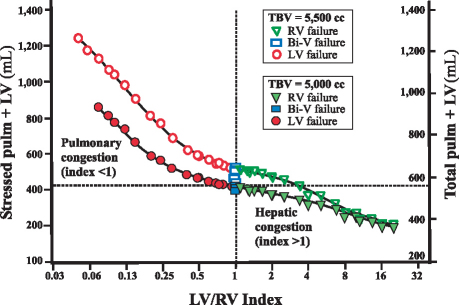

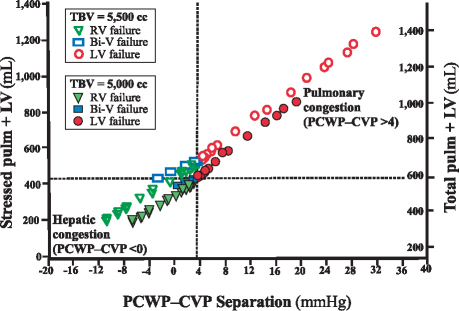

The extent of the mismatch in LV and RV contractile function was represented by the LV/RV contractile-function index. Figure 4 shows the PBV (stressed pulm + LV) as a function of the LV/RV contractile-function index. Discordant LV failure (index <1) was associated with a logarithmic increase in PBV (signifying accelerating pulmonary congestion), whereas discordant RV failure (index >1) was associated with a reduced PBV (signifying systemic or hepatic congestion). As Figure 5 shows, this passive movement in volume could also be tracked by a plot of the PBV against a surrogate marker, PCWP–CVP separation. When PCWP–CVP separation was ≥4 mmHg, we observed discordant LV failure and pulmonary congestion, which qualitatively were not changed by hypervolemia (produced by the addition of 500 cc of volume). In contrast, when PCWP–CVP separation was ≤0 mmHg, discordant RV failure and hepatic congestion were observed.

Fig. 4 Pulmonary blood volume in left ventricular (LV), right ventricular (RV), and biventricular (Bi-V) heart failure. Stressed pulmonary + left ventricular (stressed pulm + LV) volume in concordant versus discordant ventricular failure is plotted as a function of the LV and RV contractile function index. The total pulmonary volume (total pulm + LV) is also shown. Discordant LV failure (solid circles; index <1) is associated with a curvilinear increase in the stressed pulm + LV volume (left upper quadrant; stressed pulm + LV volume >410 cc; total pulm + LV volume >540 cc). Discordant RV failure (solid triangles; index >1) is associated with a decrease in stressed pulm + LV volume (right lower quadrant), or an implied increase in systemic/hepatic volume. Concordant biventricular failure (solid rectangles; index=1) is associated with lesser volume movement. Hypervolemia (total blood volume [TBV] = 5,500 cc) is denoted by an equivalent hollow circle, rectangle, or triangle. Hypervolemia changes the resting pulmonary volume but does not change the overall relationship described.

Fig. 5 Pulmonary total blood volume (TBV) in left ventricular (LV), right ventricular (RV), and biventricular (Bi-V) heart failure. The stressed pulmonary + left ventricular (stressed pulm + LV) volume in concordant versus discordant ventricular failure is plotted as a function of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure–central venous pressure (PCWP–CVP) separation. Euvolemia and hypervolemia are represented by solid and hollow markers, respectively. The total pulmonary volume (total pulm + LV) is also shown. Discordant LV failure (solid and hollow circles) is indicated by a PCWP–CVP separation of >4 mmHg. Discordant RV failure (solid and hollow triangles) is indicated by a PCWP–CVP separation of <0 mmHg. Concordant Bi-V failure (solid and hollow rectangles) parallels RV failure but to a lesser degree, with a PCWP–CVP separation of 0 to 4 mmHg. Note that hypervolemia does not change the basic relationships that allow heart-failure phenotypes to be differentiated by means of PCWP–CVP separation.

A meta-analysis of clinical data was performed to validate these model-generated concepts and hypotheses. These data included results from a study by Lewis and colleagues,19 who had discovered a close relationship between PBV and LAP index (computed from LAP and TBV) (Fig. 6). In their series,19 22 of 69 patients had a subnormal CI of <2.7 L/min/m2 (Fig. 6, inset), in accordance with Forrester and colleagues' concept of normal CI.9 Because CI is an equilibrium index, CI is not directly related to the LAP. However, LAP equates to an index of LV dysfunction, and Figure 6 shows that PBV is directly related to LAP elevation.

Fig. 6 Pulmonary blood volume (PBV) as a function of the weighted left atrial pressure (LAP) index (7.56 LAP + 0.067 total blood volume [TBV]). The data of Lewis and co-authors19 were adopted from 2 series of 69 patients (1 patient had 2 serial studies; only the 1st determination was used). The insert shows the histogram of the cardiac index (CI) in the population.

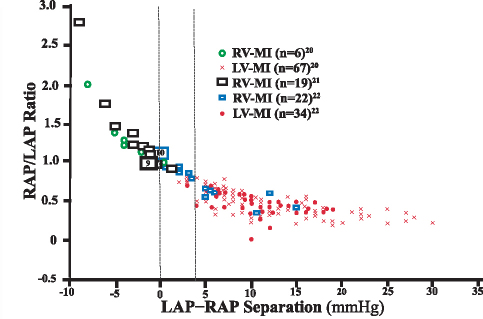

In 1974, Cohn and co-investigators20 reported the syndrome of “right ventricular infarction,” in which a myocardial infarction (MI) mainly impairs RV function, resulting in markedly elevated RAP. From a magnified view of their published plot, we obtained simultaneous LV and RV filling pressures for 67 patients with predominant LV involvement and for 6 patients with predominant RV involvement. We also extracted simultaneously measured RAP and LAP data from MI studies performed by Lopez-Sendon and colleagues22 (22 autopsy cases of RV infarction and 34 of LV infarction) and by Lloyd and associates21 (19 cases of clinical RV infarction). Figure 7 shows the combined results from these 3 studies of 148 patients. Because no cardiac output readings were consistently reported in those studies, the data were plotted by using the ratio of RAP to LAP (RAP/LAP) as a function of LAP-to-RAP difference (LAP–RAP). A curvilinear relationship was found: most RV infarctions clustered at a LAP–RAP separation of ≤0 mmHg, and most LV infarctions clustered at a LAP–RAP separation of ≥4 mmHg. The sensitivity and specificity of using a LAP–RAP delimiter of ≤0 mmHg to detect discordant RV failure (or discordant RV infarction) were 92% (34 of 37) and 100% (101 of 101), respectively. Likewise, the sensitivity and specificity of using a LAP–RAP delimiter of ≥4 mmHg to detect discordant LV failure (or discordant LV infarction) were 95% (96 of 101) and 85% (40 of 47), respectively. There was no additional benefit in using a RAP/LAP ratio of greater than 0.86 as a delimiter to identify RV infarction, as suggested by Lopez-Sendon and associates22 and later by O'Rourke and Dell'Italia.31

Fig. 7 The right atrial pressure-to-left atrial pressure (RAP/LAP) ratio is plotted as a function of LAP-to-RAP (LAP–RAP) separation. Data published by 3 different groups20–22 were combined for the analysis (total n=148). The hollow blue rectangles show right ventricular myocardial infarction (RV-MI) data and the solid red circles show left ventricular myocardial infarction (LV-MI) data, as reported by Lopez-Sendon and colleagues.22 The hollow green circles and the red crosses show RV-MI and LV-MI data, respectively, as reported by Cohn and co-authors.20 The hollow black rectangles show RV-MI data reported by Lloyd and associates.21 The vertical delimiter of ≤0 mmHg was selected for discordant RV failure as per previous modeling analysis (see Fig. 6). A vertical delimiter of ≥4 mmHg was selected for discordant LV failure (Fig. 6). Large rectangles with numbers within them show the total number of patients in each study with a LAP–RAP of 0 mmHg, depicted slightly offset from the correct position for easier graphical representation of each value.

Discussion

Heart failure involves deficient delivery of the blood supply necessary to meet the body's metabolic demand, and this deficiency is aggravated by exercise. Heart failure can have cardiac or extracardiac causes, which are generally (but not necessarily) associated with a decreased cardiac output. Heart failure is mechanistically related to elevated pulmonary venous pressure, systemic venous pressure, or both, and is often accompanied by pulmonary or systemic venous congestion. We modeled heart failure by using a hydraulic circuit in which changes in ventricular elastance (contractility) led to characteristic hemodynamic alterations that mimicked clinical heart failure.

Cardiovascular modeling studies have been conducted with different emphases, depending on the question being asked. McDonald32 and Milnor33 used fluid-dynamics modeling to explain the origin of the pressure and flow waveforms in the circulation. Braunwald and co-investigators34 modeled cardiac contractile function at the level of muscle mechanics. Stergiopulos and colleagues35,36 modeled windkessel mechanics to determine arterial compliance and pulse-wave propagation,37,38 which was instrumental in the development of continuous cardiac-output measurement algorithms that use only the pressure waveform and pulse pressure.39,40 Guyton13 was one of the first to use simplified lumped parameters to describe circuit resistance and capacitance. Today, numeric analysis can be applied to fairly complex circuits to yield instantaneous pressure and flow waveforms, which are important in the understanding of cardiopulmonary interactions, such as the phasic alteration of cardiac dynamics with respiration in tamponade physiology.41 However, in the present study, we chose the more streamlined and interactive compartmental model, which has the elegance of depicting circuit dynamics with mean pressures and flows—important in the context of clinical decision-making regarding heart-failure diagnosis and management—without sacrificing accurate representation of the fundamental cardiodynamics of the circulation.

The impact of our investigation of the physiology of heart failure and our introduction of a new physiologic/phenotypic classification of heart failure will be clarified by a review of the history of heart-failure classification, which provides a context for our new concept of discordant and concordant heart failure.

History of Heart-Failure Classification

The functional-capacity classification system for heart failure,42 introduced in its current 4-class form by the New York Heart Association in 1943 (Table I, column 1), requires neither physical diagnosis nor laboratory testing. The Killip system,43 introduced in 1967 (Table I, column 2), classifies heart-failure patients with AMI according to their extent of progressive cardiac compromise, on the basis of clinical evaluation but not objective or quantitative indices. The Forrester hemodynamic subsets (Table I, column 3)9 were formulated in the setting of acute myocardial injury to meet the need for objective hemodynamic values that exceeded the capabilities of physical diagnosis alone. The clinical presence of AMI prompted Forrester to select a CI of 2.2 L/min/m2 to discriminate between the presence and absence of inadequate clinical peripheral perfusion; this value was much lower than the level that these investigators considered to be normal (2.7 L/min/m2).9 Similarly, Forrester and associates chose a PCWP of 18 mmHg to discriminate between the presence and absence of pulmonary congestion in acute conditions. This PCWP level is often at variance with the PCWP of symptomatic patients with chronic heart failure, due to the presence of other underlying causes and of physiologic adaptive measures.44,45 Comparison of the historical Killip and Forrester data9 with respective data from contemporary AMI patients (evaluated in the year 2000) revealed the same incremental mortality rates,46 except that contemporary patients in class H-III (low CI and low PCWP) had a lower mortality rate (12%, vs 23% in the original series). This discrepancy may be related to previously unstratified RV infarction47 and to improved management of acute heart failure.

Table I. History of the Clinical Classification of Heart Failure

The Forrester classification has also been adopted in the management of acute heart failure in non-AMI circumstances,48–50 as described in a later report by Forrester and Waters51 (Table I, column 4). Acutely exacerbated chronic heart failure involves complex neurohormonal activity and alterations in peripheral resistance and capacitance, and categorical classification systems such as those of Killip and Forrester do not adequately accommodate these alterations.52 In contemporary practice, researchers have advocated the use of hemodynamic delimiters in the treatment of patients with chronic heart failure who are in acute decompensation, with the goal of reducing the PCWP to <16 mmHg and the CVP to <8 mmHg.53,54 As suggested by Nohria and coworkers,55 clinicians have further attempted to project physiologic diagnoses onto hemodynamic profiles (Table I, column 5). In this approach, they have related congestion to volume excess (elevated jugular venous pressure and PCWP, with edema and ascites) and decreased peripheral perfusion to an impaired CI. Nohria and coworkers' descriptive classification of dry-warm, wet-warm, dry-cold, and wet-cold bears an interesting similarity to the ancient classification of health and disease by the Pythagorean school, which taught that living beings were composed of 4 elements: air, fire, water, and earth, with the respective qualities of cold, hot, moist, and dry. In addition, the ancient concept described the corresponding 4 humors of the body: blood, which is hot and moist; yellow bile, which is hot and dry; black bile, which is cold and dry; and phlegm, which is cold and moist.56 Although Nohria and colleagues' approach is aesthetically appealing, it is the reverse of the approaches developed by previous investigators9 who first saw the inadequacy of subjective physical diagnosis in the management of heart failure.

In 2010, Gheorghiade and co-authors4 built upon their previous framework of heart-failure classification to further propose the use of a “congestion score” for stratifying heart-failure patients, exemplifying a trend toward viewing volume status as an overriding indicator of cardiac dysfunction. Clearly, historical approaches to classifying heart failure may not have adequately allowed for the acute versus chronic nature of the disease, a possible dynamic interaction between the greater (left-sided) and lesser (right-sided) circuits, or alterations of circulatory characteristics due to circulatory overload and altered neurohormonal milieu. Our classification system, founded upon the physiology of a complete circuit from a circulatory dynamics perspective, may therefore improve the clinical understanding of the heart-failure process by providing a fresh perspective.

Discordant and Concordant Ventricular Failure

Guyton attributed fluid mobilization in heart-failure patients to transient imbalances in biventricular output and to recruitment of the cardiovascular reflexes.13 Left ventricular failure is generally considered to cause elevations in LVEDP and LAP, which lead to pulmonary congestion.4 The CVI modeling of heart failure shows that LV failure directly causes PBV expansion and LAP elevation (Fig. 2) and that LAP and PBV are both dependent variables. This finding fully explains the close relationship between PBV and LAP.19 It is important to recognize that LAP correlates negatively with the underlying LV function, but LAP is not directly related to the equilibrium CI (Fig. 2). In contrast, PBV is directly related to LAP (Fig. 6), supporting our contention that the changes in these 2 factors are interrelated; this correlation is probably attributable to the influence of underlying cardiac contractile function on both LAP and PBV, rather than to a causal relationship between the two.

The volume movement associated with LV failure is likely to be further exaggerated by RV hyperfunction. In fact, the well-known phenomenon of exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension and congestion in mitral stenosis57 may simply equate to dynamic discordant LV failure. This insight may be important in mechanical ventricular assistance58,59 and total heart replacement,60,61 when an imbalance between the greater and lesser circulations may be an issue for optimal hemodynamic management.

A New Paradigm for Classifying Heart Failure

Because the LV is part of the greater circulation and the RV is part of the lesser circulation, we propose that the concept of discordant and concordant ventricular failure, which we introduced above by using a lumped-parameter circulatory model, be generalized into “discordant and concordant heart failure.” Table II shows our proposed physiologic/phenotypic (P) heart-failure classification system, which features 6 classes in the 2 main categories of a preserved versus a decreased CI. Each category has 3 phenotypes: 1) predominant pulmonary congestion, 2) balanced volume distribution, and 3) predominant hepatic congestion.

Table II. Our Proposed Physiologic Classification System: Discordant versus Concordant Heart Failure*

Left-sided cardiovascular diseases (Table II) include mitral and aortic valve disease, diastolic LV dysfunction, and systolic LV dysfunction. A hypertensive crisis with acute pulmonary edema in the presence of normal contractile function may be a sequela of discordant left-sided heart-failure manifestation. Right-sided cardiovascular diseases include tricuspid and pulmonic valve diseases, pulmonary parenchymal disease, and pulmonary hypertension. Concordant biventricular failure is expected to involve a balanced fluid distribution. A significant percentage of the patients in the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) substudy62 were asymptomatic with a low LV ejection fraction, possibly representative of this population. Wood63 described a clinical circumstance in patients with mitral stenosis in which a pulmonary resistance of >10 Wood units (normal value, 3 Wood units) was protective against pulmonary congestion. Carman and Lange64 observed a low-output state in patients who had surgically documented mitral stenosis without resting pulmonary hypertension or an elevated PCWP. Although the anatomic and physiologic foundations for these findings are complex, they may equate to concordant heart failure.

Fresh Clinical Perspectives in Relationship to Classical Teaching

By means of CVI modeling, we have redefined the concept of volume movement in heart failure. Although Guyton13 extensively examined the volume redistribution in animal models of heart failure, his concept of volume movement was on the basis of a transient imbalance between the 2 ventricular pumps, as well as on alterations of vasoreactivity in heart failure. In his attempts to measure the mean circulatory filling pressure, he found that when the heart was stopped, the circulatory value estimate had to be completed within 6 seconds, or there would be a significant alteration in vascular reactivity.14 Therefore, it appears that he did not fully consider the possibility that passive volume movement is a separate mechanism for volume redistribution in heart-failure patients.

The concept of volume movement in acute heart failure has been recognized as clinically relevant.65 Again, however, volume movement is thought to be primarily a result of a reduction of capacitance in the venous system (and, hence, an increase in preload) and an increase in arterial stiffness and resistance (hence, an increase in afterload). Accordingly, the contemporary understanding of pulmonary congestion relies exclusively on active volume movement and fails to consider the obligatory passive volume movement caused by discordant heart failure, which we have recognized.

Although we use the terms discordant and concordant to describe different types of heart failure, we recognize that this concept of heart failure has never been fully delineated. The clinical syndrome of “right ventricular infarction” or “predominant right ventricular dysfunction” was introduced by Cohn and colleagues20 in 1974. More recently, the term “discordant right and left ventricular failure” was used in Chatterjee's review11 of current indications for Swan-Ganz catheter use; however, this term was mainly used to describe severe RV and LV failure that cannot be adequately diagnosed without measuring the filling pressure in each ventricle. We now recognize that the traditional filling pressure so measured is more appropriately regarded as an indication of discordant right or left ventricular failure in relationship to volume movement into or out of the greater and lesser circulation.

Finally, contemporary understanding of heart-failure symptomatology, as summarized by Gheorghiade and colleagues in 2010,4 continues to consider elevation of LVEDP to be the primary cause of pulmonary venous congestion. Accordingly, without disregarding changes in ventricular stiffness as a relevant clinical measure of heart failure (the traditional explanation for the relationship between heart failure and pulmonary congestion), we recognize that the volume movement to the pulmonary space and the pressure changes in LVEDP and LAP all depend upon changes in LV function alteration. This is a fresh concept of the independent and dependent values of circulation.

Limitations

In our model, the entire peripheral circulation is viewed as one compartment, so that, for instance, the differential contribution from the splanchnic bed versus some other systemic venous bed is not modeled. In this report, we dissect the cardiovascular interactions in heart failure without specifically considering the effect of cardiac remodeling, blood volume changes, or altered autonomic tone, which would require further complex modeling and might obscure the central tenet of our research. The use of a given delimiter of the PCWP–CVP separation in our CVI modeling as a surrogate marker to identify discordant heart failure (in a simplified situation without complex valvular or pulmonary diseases) obviously does not imply that this method can be translated without qualification for clinical use. Further prospective clinical observations and appropriate adjustments of the PCWP–CVP separation or of other, analogous surrogate markers would be needed to delineate the general applicability of this principle.

Conclusions

On the basis of our study, we arrived at 5 main conclusions. 1) A “passive volume movement” is an obligatory physiologic process that, in the presence of discordant or concordant heart failure, may lead to pulmonary and hepatic congestion phenotypes. This finding negates the prevalent teaching that pulmonary congestion in LV failure is primarily or exclusively a response to the “backing up” of elevated LV filling pressure. Rather, volume mobilization to the pulmonary circulation (pulmonary congestion), an increase in LVEDP, and an increase in LAP (without disregarding or diminishing the roles of other active ventricular and vascular changes previously recognized), are important passive (dependent) changes secondary to LV failure from a mechanistic point of view. 2) Elevated LAP and CVP are indices of discordant LV and RV failure, respectively. Physiologic interpretations implying that LAP and CVP elevation are causative factors (independent variables) of pulmonary or hepatic congestion, respectively, are not appropriate interpretations, either logically or physiologically. 3) Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (a dependent variable of LV function) and CI (an equilibrium circulatory index) are not independent circulatory indices as implied in Forrester's hemodynamic-subsets classification system. 4) The general assumption that LV failure “causes” CVP elevation secondarily in the absence of volume expansion is not supported by circulatory modeling and must be reevaluated conceptually and experimentally. 5) Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure–CVP separation may be a surrogate marker of discordant and concordant heart failure. Although our analysis of published data validates this premise, its general application will need to be further refined by prospectively collecting data from patients with acute or chronic heart failure; these data may include possible confounding factors, such as complex valvular and pulmonary disease. At the same time, other surrogate markers of RV and LV dysfunction that may be elicited with the Valsalva maneuver66 may prove useful in discriminating between discordant and concordant heart failure in the clinical setting.

The heart-failure phenotypes are direct products of physiologic “series interactions” involving left- and right-sided cardiac function and left- and right-sided circulation. Our physiologic system for classifying heart failure can be most helpful when used in conjunction with the New York Heart Association functional classification system67 and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association disease-stage classification.68 For example, New York Heart Association class III and our P-LV-1 class would identify a patient with moderate discordant LV heart failure, a pulmonary congestion phenotype, satisfactory LV remodeling, and a normal CI. The advantages of our system are that physiologic classification describes the clinical status irrespective of an acute or chronic clinical presentation, and that it provides a framework whereby interventions can be targeted even if they are not immediately available (for example, assist-device therapy or administration of a specific vascular or pulmonary vasodilator). Moreover, dynamic studies of RV and LV function may lead to a better understanding of the complications of heart failure, such as the cardiorenal syndrome,69,70 in which elevation of the RAP is a characteristic manifestation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daniel Musher of the Baylor College of Medicine for reviewing this manuscript. We thank Ms Virginia Fairchild, Mrs. Angela Townley Odensky, and Dr. Stephen N. Palmer of the Texas Heart Institute for improving the clarity of the manuscript. The Cardiovascular Interactions (CVI) Project was developed by Rothe and Gersting23 at the Indiana University School of Medicine and currently consists of a 6-compartment mathematical model (available from crothe@iupui.edu or at http://www.apsarchive.org/resource.cfm?submissionID=997). The CVI Project is copyrighted but is provided for use in teaching or research if its authors are appropriately credited.

Footnotes

Address for correspondence: Tony S. Ma, MD, PhD, Section of Cardiology, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 2002 Holcombe Blvd., Houston, TX 77030

E-mail: ma_tony@sbcglobal.net

Reprints will not be available from the authors.

References

- 1.Wood PH. Diseases of the heart and circulation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1956. p. 264–317.

- 2.Burkhoff D, Tyberg JV. Why does pulmonary venous pressure rise after onset of LV dysfunction: a theoretical analysis. Am J Physiol 1993;265(5 Pt 2):H1819–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Magder S, Veerassamy S, Bates JH. A further analysis of why pulmonary venous pressure rises after the onset of LV dysfunction. J Appl Physiol 2009;106(1):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gheorghiade M, Follath F, Ponikowski P, Barsuk JH, Blair JE, Cleland JG, et al. Assessing and grading congestion in acute heart failure: a scientific statement from the acute heart failure committee of the heart failure association of the European Society of Cardiology and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12(5): 423–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cournand A, Riley RL, Breed ES, Baldwin ED, Richards DW, Lester MS, Jones M. Measurement of cardiac output in man using the technique of catheterization of the right auricle or ventricle. J Clin Invest 1945;24(1):106–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Swan HJ, Ganz W, Forrester J, Marcus H, Diamond G, Chonette D. Catheterization of the heart in man with use of a flow-directed balloon-tipped catheter. N Engl J Med 1970; 283(9):447–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Forrester JS, Diamond G, McHugh TJ, Swan HJ. Filling pressures in the right and left sides of the heart in acute myocardial infarction. A reappraisal of central-venous-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med 1971;285(4):190–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Crexells C, Chatterjee K, Forrester JS, Dikshit K, Swan HJ. Optimal level of filling pressure in the left side of the heart in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1973;289(24): 1263–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Forrester JS, Diamond G, Chatterjee K, Swan HJ. Medical therapy of acute myocardial infarction by application of hemodynamic subsets (first of two parts). N Engl J Med 1976; 295(24):1356–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Allen LA, Rogers JG, Warnica JW, Disalvo TG, Tasissa G, Binanay C, et al. High mortality without ESCAPE: the registry of heart failure patients receiving pulmonary artery catheters without randomization. J Card Fail 2008;14(8):661–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chatterjee K. The Swan-Ganz catheters: past, present, and future. A viewpoint [published erratum appears in Circulation 2009;119(21):e548]. Circulation 2009;119(1):147–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lindsey AW, Banahan BF, Cannon RH, Guyton AC. Pulmonary blood volume of the dog and its changes in acute heart failure. Am J Physiol 1957;190(1):45–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Guyton AC. Circular physiology: cardiac output and its regulation. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co.; 1963. p. 223–56.

- 14.Guyton AC, Polizo D, Armstrong GG. Mean circulatory filling pressure measured immediately after cessation of heart pumping. Am J Physiol 1954;179(2):261–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Pang CC. Measurement of body venous tone. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2000;44(2):341–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Pang CC. Autonomic control of the venous system in health and disease: effects of drugs. Pharmacol Ther 2001;90(2–3):179–230. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Rothe CF. Mean circulatory filling pressure: its meaning and measurement. J Appl Physiol 1993;74(2):499–509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Coleman TG, Manning RD Jr, Norman RA Jr, Guyton AC. Control of cardiac output by regional blood flow distribution. Ann Biomed Eng 1974;2(2):149–63.

- 19.Lewis ML, Gnoj J, Fisher VJ, Christianson LC. Determinants of pulmonary blood volume. J Clin Invest 1970;49(1):170–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cohn JN, Guiha NH, Broder MI, Limas CJ. Right ventricular infarction. Clinical and hemodynamic features. Am J Cardiol 1974;33(2):209–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lloyd EA, Gersh BJ, Kennelly BM. Hemodynamic spectrum of “dominant” right ventricular infarction in 19 patients. Am J Cardiol 1981;48(6):1016–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lopez-Sendon J, Coma-Canella I, Gamallo C. Sensitivity and specificity of hemodynamic criteria in the diagnosis of acute right ventricular infarction. Circulation 1981;64(3):515–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Rothe CF, Gersting JM. Cardiovascular interactions: an interactive tutorial and mathematical model. Adv Physiol Educ 2002;26(1–4):98–109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Rothe CF. Cardiovascular interactions: a major revision of mating an interactive lab book and a mathematical model (learning objects #973, #995, #996, and #997) [abstract]. Adv Physiol Educ 2005;29(3):139–40. Available from: http://advan.physiology.org/content/29/3/139.full.pdf+html [cited 2011 Nov 15].

- 25.Sunagawa K, Sagawa K. Models of ventricular contraction based on time-varying elastance. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 1982; 7(3):193–228. [PubMed]

- 26.Suga H, Sagawa K. Mathematical interrelationship between instantaneous ventricular pressure-volume ratio and myocardial force-velocity relation. Ann Biomed Eng 1972;1(2):160–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Sagawa K, Suga H, Shoukas AA, Bakalar KM. End-systolic pressure/volume ratio: a new index of ventricular contractility. Am J Cardiol 1977;40(5):748–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Sagawa K, Maughan L, Suga H, Sunagawa K. Cardiac contraction and the pressure-volume relationship. New York: Oxford University Press; 1988.

- 29.Guyton AC, Lindsey AW, Kaufmann BN, Abernathy JB. Effect of blood transfusion and hemorrhage on cardiac output and on the venous return curve. Am J Physiol 1958;194(2): 263–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Pepi M, Marenzi GC, Agostoni PG, Doria E, Barbier P, Muratori M, et al. Sustained cardiac diastolic changes elicited by ultrafiltration in patients with moderate congestive heart failure: pathophysiological correlates. Br Heart J 1993;70(2):135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.O'Rourke RA, Dell'Italia LJ. Diagnosis and management of right ventricular myocardial infarction. Curr Probl Cardiol 2004;29(1):6–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.McDonald DA. Blood flow in arteries. 2nd ed. London: Edward Arnold; 1974. p. 118–73.

- 33.Milnor WR. Hemodynamics. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. p. 102–41.

- 34.Braunwald E, Ross J Jr, Sonnenblick EH. Mechanisms of contraction of the normal and failing heart. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.; 1976.

- 35.Stergiopulos N, Meister JJ, Westerhof N. Evaluation of methods for estimation of total arterial compliance. Am J Physiol 1995;268(4 Pt 2):H1540–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Stergiopulos N, Westerhof BE, Westerhof N. Total arterial inertance as the fourth element of the windkessel model. Am J Physiol 1999;276(1 Pt 2):H81–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Stergiopulos N, Meister JJ, Westerhof N. Determinants of stroke volume and systolic and diastolic aortic pressure. Am J Physiol 1996;270(6 Pt 2):H2050–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Stergiopulos N, Westerhof N. Determinants of pulse pressure. Hypertension 1998;32(3):556–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Jansen JR, Schreuder JJ, Mulier JP, Smith NT, Settels JJ, Wesseling KH. A comparison of cardiac output derived from the arterial pressure wave against thermodilution in cardiac surgery patients. Br J Anaesth 2001;87(2):212–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Wesseling KH, Jansen JR, Settels JJ, Schreuder JJ. Computation of aortic flow from pressure in humans using a nonlinear, three-element model. J Appl Physiol 1993;74(5): 2566–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Ramachandran D, Luo C, Ma TS, Clark JW Jr. Using a human cardiovascular-respiratory model to characterize cardiac tamponade and pulsus paradoxus. Theor Biol Med Model 2009;6:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association. Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of diseases of the heart. 4th ed. New York: New York Tuberculosis & Health Association, Inc.; 1943. p. 9–10.

- 43.Killip T 3rd, Kimball JT. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am J Cardiol 1967;20(4):457–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Stevenson LW, Perloff JK. The limited reliability of physical signs for estimating hemodynamics in chronic heart failure. JAMA 1989;261(6):884–8. [PubMed]

- 45.Chakko S, Woska D, Martinez H, de Marchena E, Futterman L, Kessler KM, Myerberg RJ. Clinical, radiographic, and hemodynamic correlations in chronic congestive heart failure: conflicting results may lead to inappropriate care. Am J Med 1991;90(3):353–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Siniorakis E, Arvanitakis S, Voyatzopoulos G, Hatziandreou P, Plataris G, Alexandris A, Bonoris P. Hemodynamic classification in acute myocardial infarction. Chest 2000;117(5): 1286–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Madias JE. Killip and Forrester classifications: should they be abandoned, kept, reevaluated, or modified? Chest 2000;117 (5):1223–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Chatterjee K, Parmley WW, Ganz W, Forrester J, Walinsky P, Crexells C, Swan HJ. Hemodynamic and metabolic responses to vasodilator therapy in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1973;48(6):1183–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Miller RR, Awan NA, Maxwell KS, Mason DT. Sustained reduction of cardiac impedance and preload in congestive heart failure with the antihypertensive vasodilator prazosin. N Engl J Med 1977;297(6):303–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Awan NA, Miller RR, Mason DT. Comparison of effects of nitroprusside and prazosin on left ventricular function and the peripheral circulation in chronic refractory congestive heart failure. Circulation 1978;57(1):152–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Forrester JS, Waters DD. Hospital treatment of congestive heart failure. Management according to hemodynamic profile. Am J Med 1978;65(1):173–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Seino Y, Shimai S, Tanaka K, Takano T, Hayakawa H. Cardiovascular circulatory adjustments and renal function in acute heart failure. Jpn Circ J 1989;53(2):180–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Binanay C, Califf RM, Hasselblad V, O'Connor CM, Shah MR, Sopko G, et al. Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial. JAMA 2005;294(13):1625–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Stevenson LW. Are hemodynamic goals viable in tailoring heart failure therapy? Hemodynamic goals are relevant. Circulation 2006;113(7):1020–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Nohria A, Tsang SW, Fang JC, Lewis EF, Jarcho JA, Mudge GH, Stevenson LW. Clinical assessment identifies hemodynamic profiles that predict outcomes in patients admitted with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41(10):1797–804. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Katz AM. Knowledge of the circulation before William Harvey. Circulation 1957;15(5):726–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Harvey RM, Ferrer I, Samet P, Bader RA, Bader ME, Cournand A, Richards DW. Mechanical and myocardial factors in rheumatic heart disease with mitral stenosis. Circulation 1955;11(4):531–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, John R, Boyle AJ, Aaronson KD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med 2007;357(9): 885–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, Russell SD, Conte JV, Feldman D, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(23):2241–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Fukamachi K, Massiello AL, Kiraly RJ, Chen JF, Himley S, Davies C, et al. Effects of a total artificial heart right stroke volume limiter on left-right hemodynamic balance. ASAIO J 1993;39(3):M410–4. [PubMed]

- 61.Abe Y, Isoyama T, Saito I, Mochizuki S, Ono M, Nakagawa H, et al. Development of mechanical circulatory support devices at the University of Tokyo. J Artif Organs 2007;10(2): 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Francis GS, Benedict C, Johnstone DE, Kirlin PC, Nicklas J, Liang CS, et al. Comparison of neuroendocrine activation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction with and without congestive heart failure. A substudy of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). Circulation 1990;82(5): 1724–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Wood P. An appreciation of mitral stenosis. I. Clinical features. Br Med J 1954;1(4870):1051–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Carman GH, Lange RL. Variant hemodynamic patterns in mitral stenosis. Circulation 1961;24(4):712–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Cotter G, Metra M, Milo-Cotter O, Dittrich HC, Gheorghiade M. Fluid overload in acute heart failure–re-distribution and other mechanisms beyond fluid accumulation. Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10(2):165–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Gorlin R, Knowles JH, Storey CF. The Valsalva maneuver as a test of cardiac function; pathologic physiology and clinical significance. Am J Med 1957;22(2):197–212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association, Inc. Diseases of the heart and great vessels: nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis. 6th ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.; 1964. p. 112–3.

- 68.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2005;112(12):e154–235. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Nohria A, Hasselblad V, Stebbins A, Pauly DF, Fonarow GC, Shah M, et al. Cardiorenal interactions: insights from the ESCAPE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(13):1268–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Jessup M, Costanzo MR. The cardiorenal syndrome: do we need a change of strategy or a change of tactics? J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53(7):597–9. [DOI] [PubMed]