Abstract

Background

Residual confounding is challenging to detect. We recently described a method for detecting confounding and justified it primarily for time-series studies. The method depends on an indicator with two key characteristics: (1) it is conditionally independent (given measured exposures and covariates) of the outcome, in the absence of confounding, misspecification and measurement errors; and (2) like the exposure, it is associated with confounders, possibly unmeasured. We proposed using future exposure levels as the indicator to detect residual confounding. This choice seems natural for time-series studies because future exposure cannot have caused the event, yet they could be spuriously related to it. A related question – addressed here – is whether an analogous indicator can be used to identify residual confounding in a study based on spatial, rather than temporal, contrasts.

Methods

Using directed acyclic graphs, we show that future air pollution levels may have the characteristics appropriate for an indicator of residual confounding in spatial studies of environmental exposures. We empirically evaluate performance for spatial studies using simulations.

Results

In simulations based on a spatial study of ambient air pollution levels and birth weight in Atlanta, and using ambient air pollution one year after conception as the indicator, we were able to detect residual confounding. The discriminatory ability approached 100% for some factors intentionally omitted from the model, but was very weak for others.

Conclusion

The simulations illustrate that an indicator based on future exposures can have excellent ability to detect residual confounding in spatial studies, although performance varied by situation.

Keywords: confounding, spatial epidemiology, directed acyclic graphs, causal effects, air pollution, environmental

Residual confounding is difficult to detect, in part because assessment must be based on causal considerations. It is not enough to model statistical associations accurately, as associations may not mirror causal patterns.1

We have previously proposed a method for detecting residual confounding or other forms of model misspecification on the tenet that a cause must precede its effect.2,3 The method utilizes a variable with two key characteristics. The variable should be independent of disease, absent confounding or other misspecification, and it should be associated with the exposure and confounding covariates. Emphasizing time-series studies, we previously argued that future levels of many environmental exposures can often have the needed characteristics: future exposures cannot have caused past disease, and so an association with prior disease can be spurious.

Using future exposure variables in time-series studies to detect temporal confounding is intuitively attractive – future exposures cannot have caused prior health events and yet could be spuriously related to the event. A related question is whether an analogous variable can be used in spatial studies to identify residual confounding, such as in studies where region-specific pollutant concentrations are correlated with region-specific disease rates. Risk factors such as smoking could co-vary with pollutant concentrations across regions and thus lead to spatial confounding. Although the nature of confounding differs between spatial and time-series studies,4 the previously proposed method for detecting residual confounding can be similarly applied in spatial studies. We present simulation results that evaluate the method’s performance and discuss its strengths and weaknesses.

Methods

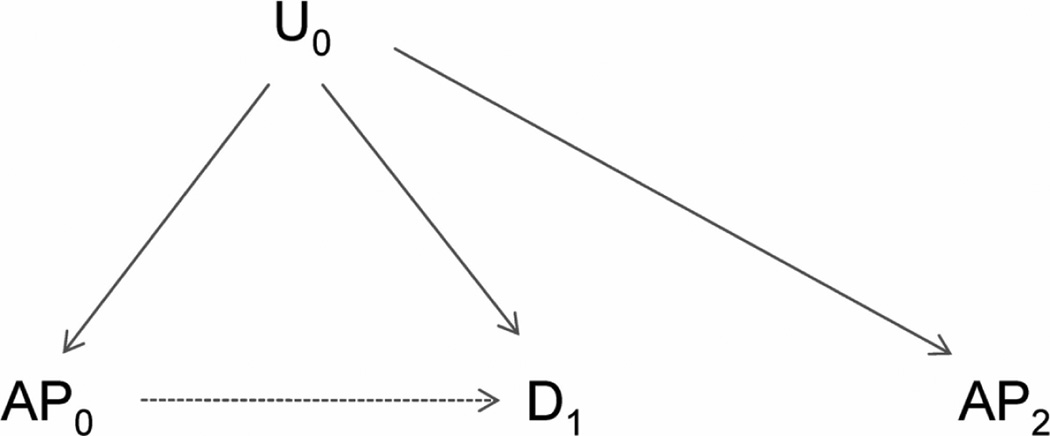

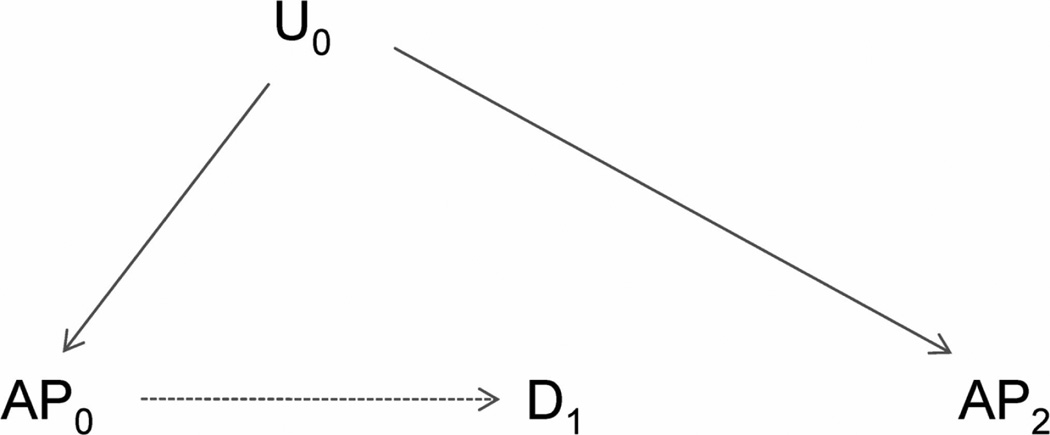

To illustrate the approach for spatial studies, we consider a study whose objective is to assess the association of area-specific air pollution levels (e.g., ambient ozone, AP0 in the directed acyclic graph5,6 in Figure 1) with the birth weight of newborn infants in the same area (D1 in Figure 1). An important presumption is that birth weight (D1) does not affect future pollution levels (AP2), reflected by the absence of an arrow from D1 to AP2. Furthermore, spatial factors that affect health and are associated with future pollution levels (e.g., poverty) should often also be associated with earlier pollutant levels, illustrated by U0 (Figure 1). If these relationships hold, we argue in the eAppendix 1 (http://links.lww.com) – and previously for time-series studies3 – that, conditional on AP0, future air pollutant levels should not be associated with disease in the absence of confounding (Figure 2), but associated in its presence (Figure 1). In this case, future pollutant levels have key characteristics needed for an indicator of unmeasured confounding2,3 and can be used to detect it or other model mis-specification.

Figure 1.

Directed acyclic graph showing basic causal relationships among exposure (air pollution, AP0), the health outcome (birth weight, D1), an unmeasured covariate (U0) and future air pollution (AP2). Confounding by U1 is present, indicated by the backdoor path from AP0 to D1.

Figure 2.

Directed acyclic graph showing basic causal relationships among exposure (air pollution, AP0), the health outcome (birth weight, D1), an unmeasured covariate (U0) and future air pollution (AP2). Confounding by U1 is absent, as there is no open backdoor path from AP0 to D1.

The model used to analyze the study should include the exposure of interest (air pollutant level prior to outcome occurrence, APa,i) and relevant covariates. Equation (1) illustrates a linear form:

| (1) |

For infant i in area a, E(Ya,i) is the expected birth weight and APa,i is a relevant, prenatal air pollutant level.

To use future area-specific air pollutant levels as an indicator, we also fit the same model that now also includes the indicator variable (area-specific, pollutant level measured after infant i's birth, say APa,if):

| (2) |

If residual confounding and model mis-specification are absent and the assumed causal relationships are adequate approximations, APa,if should be unassociated with Ya,i after adjustment for covariates. An association between APaf and the outcome (δ ≠ 0) suggests residual confounding or other model misspecification. Thus, we use the statistic I to test for residual confounding:

| (3) |

where δ̂ is the estimated slope and σ̂f its standard error. Under the null hypothesis of no model misspecification, I is approximately normally distributed.

Simulations

We assess the indicator’s ability to detect residual confounding using data from a spatial study of ambient air pollution and birth weight in Atlanta. Use of simulations allows us to specify the “true” causal relationships; using estimated parameters to calculate the “true,” expected birth weights makes the simulations realistic. We consider two ambient pollutants commonly assessed in the birth outcomes literature, PM2.5 (micrograms per meter3) and NO2 (parts per billion, ppb). We assess relationships between pollutant levels during the first month of pregnancy and birth weight of full-term infants. Zip code-specific levels for each pollutant were a weighted average estimate.7

Each full-term infant (37 to 43 weeks’ gestation) was assigned to the zip code of the mother’s residence. We calculated the ambient air pollution level for each infant’s zip code, averaged over the four weeks following the estimated conception date. Modeled covariates included: gestational age (weekly indicators); maternal education, age (linear spline with three knots), tobacco use (yes/no), Medicaid (yes/no), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, African American and Hispanic); and the zip code’s percent of population below poverty. We included indicators for date-of-conception in two-week intervals, so comparisons were spatial.

We also calculated the air pollution level for each zip code averaged over the four-week period beginning one year after the conception date. Because these exposures occurred after birth (8+ weeks), they cannot have affected birth weight. Future levels (APi,af) are included only in models that also include pollutant levels prior to birth and a subset of the covariates.

We used the model in Equation (1), with zip code as the area. We fit this model (once) to the observed birth weights to obtain model-predicted weights for each infant, and then treated the model-predicted weights as the true expected value in the simulations. To assess the indicator’s ability to detect confounding, we first generated a birth weight for each infant, using the “true” predicted values and adding a random Gaussian error. We fit the correct model including the indicator, and then, to simulate confounding, we fit the misspecified model (incorrectly omitting a factor) along with the indicator. In most scenarios, we omitted an actual, measured factor (e.g., smoking). In a few situations, we created a hypothetical factor and included it when fitting the model to obtain alternative “true” predicted weights. We subsequently omitted the variable to simulate additional patterns of confounding. We calculated the proportion of simulations in which I exceeded 1.96 in absolute value, rejecting the null hypothesis of no confounding. We also calculated the area under the receiver operating curve as a measure of discriminatory ability. We include a program for simulating the power to detect model misspecification due to omission of a confounder (eAppendix 2, http://links.lww.com). The user can either specify parameters to generate data hypothetically, or use actual observations to fit a model and base simulations on the fitted parameters.

Results

PM2.5 was negatively associated with birth weight in these spatial analyses (Table 1, Scenario 1; β̂ = 20.6/grams/10 µg/m3). Compared with the “true” model that generated the data, improperly omitting various variables led to varying degrees of simulated confounding. β̂ changed by about 70% when age was omitted and by 700% when race was omitted (Table 1, column 3). The indicator’s ability to detect simulated confounding also varied substantially. For the situations considered, the indicator’s ability was weak when confounding was weak to modest, as when age or tobacco was omitted (AUC = 0.51 – 0.56, Table 1, column 5). However, this was sample-size dependent: with quadrupling of the sample size, the ability to detect confounding (created when the poverty variable is incorrectly omitted increased from 19% (Table 1) to over 50% (data not shown). With stronger degrees of simulated confounding, the indicator consistently signaled that confounding might be a problem (e.g., scenarios 5 and 6; AUC = 0.93 –1.00, Table 1).

Table 1.

Simulation Results. True (connect) Modela stipulates An Effect of Exposure (PM2.5) on Birth Weight

| Scenario | Median β̂b (SE (β̂)) |

Percent Bias |

Median ( I ) | Proportion of Simulations in which Null is Rejected (Ho: δf= 0) |

AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (correct model)a |

−20.6 (17.2) | − | −0.01 | 0.050 | 0.50 |

| 2 (drop tobacco) |

0.0(17.3) | 100 | 0.64 | 0.086 | 0.56 |

| 3 (drop age) | − 5.8 (17.3) | 72 | 0.19 | 0.042 | 0.51 |

| 4 (drop percent below poverty) |

−50.6 (17.1) | 146 | −1.06 | 0.184 | 0.65 |

| 5 (drop Medicaid, tobacco, age, education) |

61.4 (17.4) | 398 | 1.85 | 1.00 | 0.93 |

| 6 (Drop Race) | −168. (17.3) | 716 | −5.48 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Correct model includes indicator for estimated date of conception (2-week intervals), gestational age (weeks), maternal tobacco use, education, age, and Medicaid status, and zip-code-specific percent below poverty line and PM2.5 (see text).

β̂ is the estimated change in birth weight (gms), per 10 ug/m3 change in PM2.5.

AUC indicates the area under the receiver operating curve; it is 0.5 in the absence of discriminatory ability and 1.0 for perfect discriminatory ability

Simulation results were similar for NO2 (Table 2), and also when we considered confounding by the hypothetical factors (Table 3). While the ability to detect confounding again varied, the indicator consistently signaled possible residual confounding with these sample sizes when the degree of simulated confounding was moderate to strong (e.g., when race or several variables were omitted (Table 2, scenarios 5 and 6).

Table 2.

Simulation Results. True Modela (correct) stipulates An Effect of Exposure (NO2) on Birth Weight

| Scenario | Median β̂b (SE (β̂)) |

Percent Bias |

Median (| I |) | Proportion of Simulations in which Null is Rejected (Ho: δf= 0) |

AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (correct model)a |

−12.1 (8.0) | − | −0.01 | 0.052 | 0.50 |

| 2 (drop tobacco) |

−6.90 (8.0) | 44 | 0.28 | 0.054 | 0.51 |

| 3 (drop age) | − 8.9 (8.0) | 26 | 0.07 | 0.048 | 0.50 |

| 4 (drop percent below poverty) |

−18.4 (8.0) | 52 | −0.55 | 0.106 | 0.55 |

| 5 (drop Medicaid, tobacco, age, education) |

7.9 (8.2) | 165 | 1.27 | 0.224 | 0.68 |

| 6 (Drop Race) | −48.2 (8.0) | 298 | 2.00 | 0.521 | 0.86 |

Correct model includes indicator for estimated date of conception (2 week intervals), gestation age (weeks), maternal tobacco use, education, age, and Medicaid status, and zip code-specific percent below poverty line and NO2 (see text).

β̂ is the estimated change in birth weight (gms), per 20 ppm change in NO2.

Table 3.

Simulation Results. True (correct) Modela stipulates An Effect of Exposure (PM2.5) on Birth Weight.

Hypothetical Factors Cov1 – Cov3 were generated, with specified effects and correlations.

| Scenario | Median β̂b (SE (β̂)) |

Percent Bias |

Median (I) | Proportion of Simulations in which Null is Rejected (Ho: δf= 0) |

AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (correct model) |

−20.9 (17.2) | − | −0.01 | 0.050 | − |

| 2 (drop Covariate 1c) |

−10.0 (17.4) | 3 | 0.35 | 0.056 | 0.52 |

| 3 (drop Covariate 2c) |

31.2 (18.9) | 49 | 1.59 | 0.345 | 0.79 |

| 4 (drop Covariate 3c) |

78.1 (20.8) | 274 | 2.08 | 0.690 | 0.93 |

Correct model includes indicator for estimated date of conception (2 week intervals), gestation age (weeks), maternal tobacco use, education, age, and Medicaid status, and zip code-specific percent below poverty line, PM2.5 and hypothetical variables Covariates 1–3, with progressively stronger effect on birth weight (see text and footnote 4, below).

β̂ is the estimated change in birth weight (gms), per 10 ppm change in PM2.5.

β for Covariates 1, 2, and 3: 50, 200, and 300 respectively.

Discussion

We extend a method to detect important residual confounding2,3 by describing and evaluating the method for spatial studies. The ability to detect residual confounding was excellent for some scenarios, such as when race was intentionally omitted. As with any statistical technique, the ability to detect residual confounding improves with stronger confounding and larger sample size. We omitted measured variables, such as race, merely to illustrate possible scenarios based on relationships of real factors. In actual applications, the factor creating confounding, if any, could be completely unrecognized and unmeasured. Although few researchers would omit race from a study of air pollution and birth weight, an investigator could conceivably be unaware of, and therefore omit, some other factor that affected air pollution and birth weight in a way similar to race.

The validity of this approach depends on the assumptions. False-positive indications could arise if, for example, a factor affected both the outcome and future exposures but not the exposure of interest. Our simulations suggest that the method can discriminate situations where residual confounding is present from those where it is not, although the strength of this discrimination ability varies according to the situation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Financial Support: This work was supported by the following grants: EPA STAR RD83479901 and RD833626, NIEHS R01ES11294 and EPRI EP-P277231/C13172. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies, and mention of any products or commercial services does not constitute endorsement.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SDC Supplemental digital content is available through direct URL citations in the HTML and PDF versions of this article (www.epidem.com).

References

- 1.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(2):176–184. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flanders WD, Klein M, Strickland M, Darrow L, Sarnat S, Sarnat J, Waller L, Tolbert PE. A method of identifying residual confounding and other violations of model assumptions. Epidemiol. 2009:s44–s45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flanders WD, Klein M, Strickland M, Darrow L, Sarnat S, Sarnat J, Waller L, Winquist A, Tolbert PE. A Method for Detection of Residual Confounding in Time-Series and Other Observational Studies. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):59–67. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fdcabe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strickland MJ, Klein M, Darrow LA, Flanders WD, Correa A, Marcus M, Tolbert PE. The issue of confounding in epidemiological studies of ambient air pollution and pregnancy outcomes. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2009;63(6):500–504. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins J. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenland S, Pearl J. Causal diagrams. In: Boslaugh S, editor. Encyclopedia of Epidemiology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. pp. 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivy D, Mullholland JA, Russell AG. Development of Ambient Air Quality Population-Weighted Metrics for Use in Time-Series Health Studies. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 2008;58(5):711–720. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.58.5.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.