SUMMARY

PURPOSE

To describe high frequency (HF) electrographic activity accompanying ictal discharges in the tetrodotoxin (TTX) model of infantile spasms. Previous studies of HF oscillations in humans and animals suggest that they arise at sites of seizure onset. We compared HF oscillations at several cortical sites to determine regional differences.

METHODS

TTX was infused for 4 weeks into the neocortex of rats beginning on postnatal days 11 or 12. EEG electrodes were implanted two weeks later and Video/EEG recordings were analyzed between postnatal days 31–47. EEGs were digitally sampled at 2048 Hz. HF EEG activity (20–900 Hz) was quantified using compressed spectral arrays and band-pass filtering.

RESULTS

Multiple seizures were analyzed in 10 rats. Ictal onset was associated with multiple bands of rhythmic HF activity that could extend to 700 Hz. The earliest and most intense discharging typically occurred contralaterally to where TTX was infused. HF activity continued to occur throughout the seizure (even during the electrodecrement that is recorded with more traditional filter settings), although there was a gradual decrease of the intensity of the highest frequency components as the amplitude of lower frequency oscillations increased. Higher frequencies sometimes reappeared in association with spike/sharp waves at seizure termination.

DISCUSSION

The findings show that HF EEG activity accompanies ictal events in the TTX model. Results also suggest that the seizures in this model do not originate from the TTX infusion site. Instead HF discharges are usually most intense and occur earliest contralaterally, suggesting that these homologous regions may be involved in seizure generation.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Seizures, Spasms, TTX, High Frequency Oscillations, EEG

INTRODUCTION

While traditional EEG recordings have commonly been limited to an analysis of frequencies less than 100 Hz, there has been a growing appreciation that important information is found at much higher frequencies (Rampp and Stefan, 2006; Engel, Jr. et al., 2009). In terms of normal EEG activity, ripple oscillations in the 100 – 200 Hz range, recorded in temporal lobe structures, are thought to play a role in consolidating synaptic plasticity and memories (Llinas, 1988; Lisman and Idiart, 1995; Bragin et al., 1999). Higher frequencies (200 – 600 Hz) have been recorded in the somatosensory cortex following peripheral or thalamic stimulation and are thought to be produced by a rapid integration of ascending sensory information (Curio, 2000). Numerous studies have reported HF oscillations in humans with epilepsy and in animal models. In temporal lobe epilepsy localized activity in the 250–600 Hz range is associated with interictal spikes, and these regions may be sites of seizure generation (Bragin et al., 2002a; Bragin et al., 2002b). Consistent with this notion is the observation that, at least in rodent models, similar activity may occur at the onset of ictal events (Bragin et al., 2005). Several other studies have suggested that HF oscillations occur at or preceding the onset of ictal events in human neocortical epilepsy, but again in a highly localized manner (Traub et al., 2001; Worrell et al., 2004; Jirsch et al., 2006). Taken together these observations suggest that these fast oscillations may be biomarkers for identifying epileptogenic brain circuits.

Recordings in both hippocampus and neocortex have contributed significantly to an appreciation of the potential roles HF oscillations play in the generation of both interictal and ictal discharges. For infants with infantile spasms, depth electrode recordings are rarely performed since these children are commonly not candidates for epilepsy surgery. Despite this, in recent years studies have utilized digital scalp EEG recordings to describe high frequency activity during infantile spasms (Panzica et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 2004; Panzica et al., 2007; Inoue et al., 2008). However, results from these recordings differ in the frequency of the oscillations recorded and their location. For example, Kobayashi and colleagues (Kobayashi et al., 2004) analyzed EEGs from 8 patients with infantile spasms and reported bilateral rhythmic 50–100 Hz activity in association with ictal discharges. More recently Inoue and colleagues (Inoue et al., 2008) extended these observations in 15 patients and suggested that activity with spectral peaks up to 120 Hz was most prominent in occipitoparietal regions compared to frontocentral. On the other hand, Panzica et al. (1999, 2007) reported asymmetric rhythmic bursts of fast activity in the 15–27 Hz range. Differences in patient selection, recording, and analysis methods employed and/or the instrumentation used may explain these differences.

The availability of animal models of temporal lobe epilepsy has been beneficial in furthering an understanding of the potential role HF oscillations play in seizure generation. We previously described an animal model of infantile spasms based upon local neocortical infusion of tetrodotoxin (TTX) in infant rats beginning 11–12 days after birth (Lee et al., 2008). In these rats, spasms are brief (1–2 secs) and characterized by flexion or extension of the trunk and/or forelimbs. The ictal and interictal EEG patterns are also very similar to those seen in human infants with infantile spasms with very frequent, high amplitude, multifocal spikes and sharp waves, and a hypsarrhythmic pattern is often present, particularly during slow wave sleep. As in humans, spasms in this animal model often occur in clusters, especially following arousal from sleep. Additional criteria for an ideal model of infantile spasms (Stafstrom, 2009), which include responsiveness to ACTH and cognitive impairment have yet to be fully evaluated in this model. The studies reported here were conducted to explore the possibility that HF neocortical oscillations accompany spasms in the TTX model.

METHODS

TTX infusion

Details of the methodology have been described previously (Galvan et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2008). Briefly, 11–12 day old rats were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and an osmotic infusion minipump filled with a 10 μM solution of TTX was implanted subcutaneously along the animal’s dorsum. (In two control animals the pump was filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid vehicle only). The pump was connected to a 28 gauge stainless steel cannula that was stereotaxically placed (AP: 2.0: ML: 2.2; DV: 0.8 mm) in the right central cortex (IS in Figure 1A) and anchored with dental acrylic. Infusion of TTX (0.25 μl/hr) or vehicle was continued for 28 days. All procedures used in this study were approved by the Baylor College of Medicine animal welfare committee and were in keeping with guidelines established by the NIH.

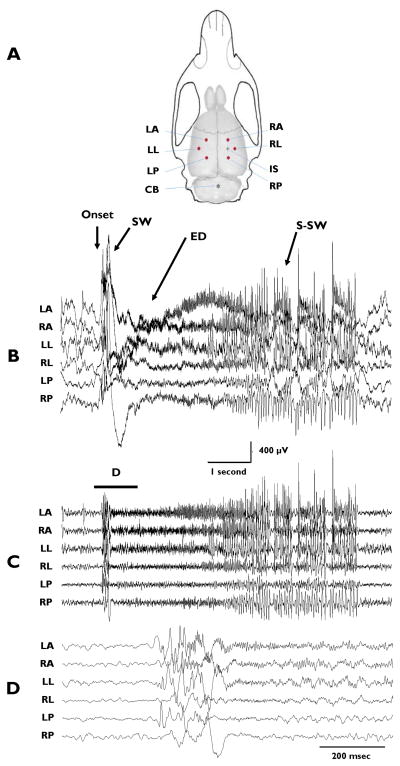

Figure 1.

A: Illustration of rat skull and brain showing locations of recording electrodes (Dots), reference electrode (Asterisk), and TTX infusion site (+). Recording electrodes were positioned 3.0 mm from infusion site as well as homotopically in contralateral cortex. (LA = left anterior, RA = right anterior, LL = left lateral, RL = right lateral, LP = left posterior, RP = right posterior, IS = infusion site, CB = cerebellar reference electrode) B–D: An ictal event recorded from TTX-treated rat. B: 8-second EEG recording filtered at 0.5–900 Hz. C: Same as B but filtered at 20 – 900 Hz to illustrate HF components. D: Expanded traces (1 second duration) of the segment of the traces in Panel C denoted by line labeled D. Arrow in Panel B indicates time of seizure onset. SW denotes slow wave complex at seizure onset. ED denotes electrodecremental period. S-SW indicates spike and sharpwave complexes.

EEG recordings

Recording electrodes were implanted 0.8 mm below the cortical surface at 6 cortical locations, as indicated in Figure 1A, two weeks after pump implantation. Reference electrodes were placed in the cerebellum and neck musculature. The recording sites were chosen with relation to the TTX infusion site. Our initial study (Galvan et al., 2000), used the 2-deoxyglucose method (Sokoloff et al., 1977) to detect changes in glucose consumption associated with altered neuronal activity. This indicated that neuronal activity was blocked within a volume of tissue approximately 2.5 mm in diameter centered at the infusion site. Since seizures were recorded in this and previous studies while TTX was still being infused, we reasoned that they could not be generated within the infusion site but instead might be generated in the surrounding cortical circuits – possibly due to compensatory mechanisms that produced an excitatory surround. Based on this reasoning, we placed 3 electrodes ipsilateral to the infusion site 3 mm anterior, posterior and lateral to the cannula implantation site. These electrodes were denoted as right anterior (RA), right posterior (RP) and right lateral (RL). Three additional electrodes were placed homotopically in the contralateral cortex and are referred to as left anterior (LA), left posterior (LP) and left lateral (LL). In three animals, additional EMG recording electrodes were placed in the facial (in the vicinity of the vibrissae) and neck (near the auricle) musculature in order to record EMG activity associated with seizures. Cortical and EMG electrodes were 0.005″ (127 μm - bare diameter) Teflon-coated silver wires exposed for 0.3 – 0.5 mm at the tip. Usually monitoring sessions of 4–8 hours per day were conducted for at least 5 –6 days between postnatal days 31– 47. Recordings were made with a Nicolet/Viasys instrument using a digital sampling rate of 2048 Hz. To allow free movement of rats during recording sessions a commutator (Plastic One) was employed.

Data analysis

The results reported here were based on analysis of EEGs recorded from 10 TTX-treated rats and 2 ACSF-infused controls. While we have recorded spasms associated with ictal EEG events in rats as early as postnatal day 15, for the purposes of this investigation we chose to study slightly older rats (ages 31– 47 days) when seizures were more established and frequent. Nine of the experimental rats and both controls were from this age range. The tenth TTX infused animal was 70–75 days old when recordings were analyzed.

High frequency EEG activity associated with ictal events was quantified using narrow band-pass filtering and compressed spectral arrays. The filters were designed to provide an attenuation of 31 db/octave beyond the cut-off point. Compressed spectral arrays (Bickford et al., 1972) were derived from EEG segments of 1 to 8 sec. duration, using a 100 msec sliding analysis window which was advanced through the digitized sample in increments of 10 data points (equivalent to 5 msec). The 100 msec data samples were multiplied by a cosine-tapered (Tukey) window with a 20% taper-to-constant ratio prior to computation of the fast fourier transform (FFT). The compressed FFT arrays were displayed as contour plots with frequency on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis. Spectral amplitude (square root of power spectral density) was indicated by a color-code. This procedure permitted a frequency range of 10 to 900 Hz with a frequency resolution of 10 Hz, and an ability to determine the onset time of spectral components with a resolution of 5 msec. Because of the sliding analysis window, the ability to resolve distinct spectral components of the same frequency is limited to those separated by more than 100 msec. In addition, very brief, discrete, frequency components, such as those associated with a spike, are stretched temporally as the 100 msec sliding analysis window passes over, and this may result in columnar-appearing events of approximately 100 msec duration in the spectral plot. Analysis software was developed using the Matlab programming language. The spectral displays used here are similar in concept to those used in published human studies (Kobayashi et al., 2004; Panzica et al., 2007).

Statistics

Data are summarized as means ± SEM. However in Figure 5E, since results from all groups did not have equal variance, the bars on histograms plot the range of measures. A one way ANOVA was performed to determine statistical significance. For comparisons when equal variance test failed a Kruskal-Wallis one way ANOVA was used. A post-hoc Tukey test was used to correct for multiple comparisons. Sigma Stat was used to perform all statistical tests.

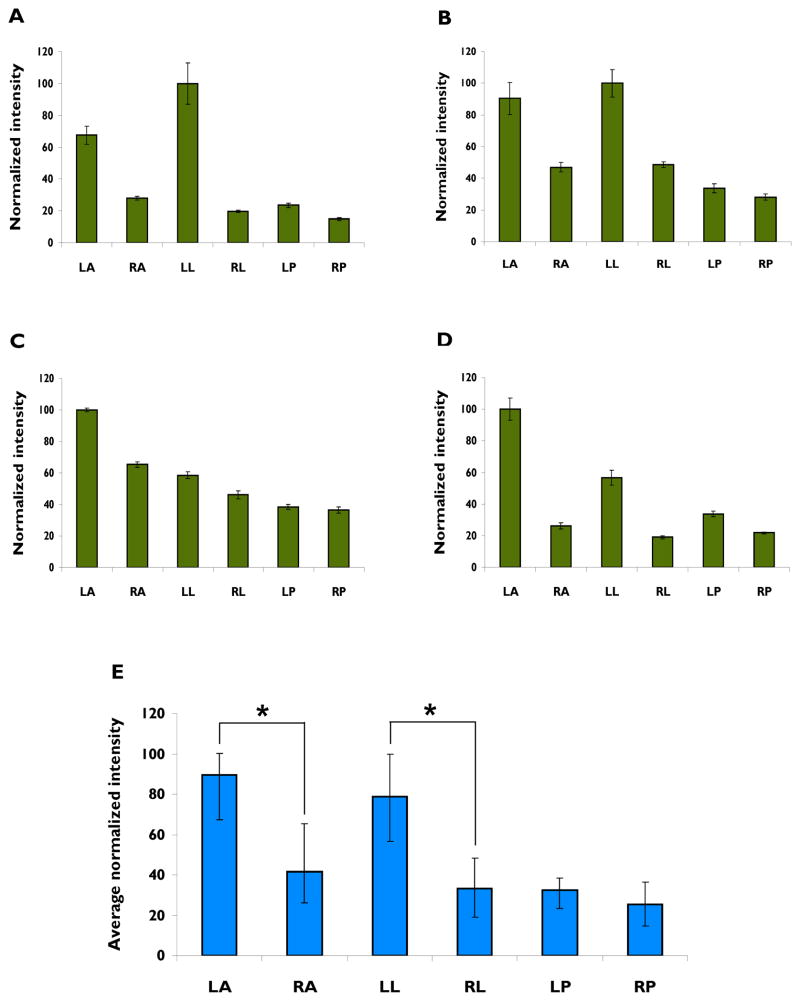

Figure 5.

Comparison of the intensity of high frequency EEG activity associated with ictal events at 6 recording sites in 4 rats. A –D. Each of the 4 graphs shows the average intensity (square root of total power) of EEG activity in the 50 –900 Hz range in all 6 cortical recording sites during the initial 200 msec of ictal activity. Each panel is the result of the analysis of 5 seizures in a different TTX-treated animal. Spectral intensities at each recording site for each animal were normalized (to the cortical site having the highest average intensity for that animal). Error bars are SEM. E. Bar heights represent overall averages computed from the mean value of the data shown in A – D. Error bars in this section delineate the range of individual normalized values that contributed to the mean. *p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

High frequency EEG activity during ictal events

The results of this study document the presence of significant high frequency EEG components up to 700 Hz during ictal events associated with epileptic spasms in the TTX model of infantile spasms. Multiple seizures associated with behavioral spasms were analyzed in 10 rats. In the representative example shown in Figure 1B–D, the onset of the ictal event is indicated by the arrow where a large slow wave (SW) is followed by an electrodecrement (ED). However, these high frequency recordings (0.5–900 Hz) also show a thickening of the traces during the ictal event – especially in recordings from the LA, RA and LL electrodes -- reflecting the presence of high frequency activity. The traces in Panel C are the same recordings as in B but show the HF activity in relative isolation by using a 20–900 Hz band-pass filter. Not all regions of the neocortex generate HF events to the same extent. Notice that the RL, LP and RP channels do not display as marked an increase in HF activity at the beginning of the ictal complex. This is also illustrated in Panel D where the time window marked by the line D in Panel C is shown at a faster time base (20–900 Hz band-pass filter). Notice that the HF activity in the top three traces of Panel D differs dramatically from the baseline EEG activity recorded prior to the onset of the seizure by the same electrodes. Such oscillations are much less apparent in recordings from the RL, LP, and RP electrodes.

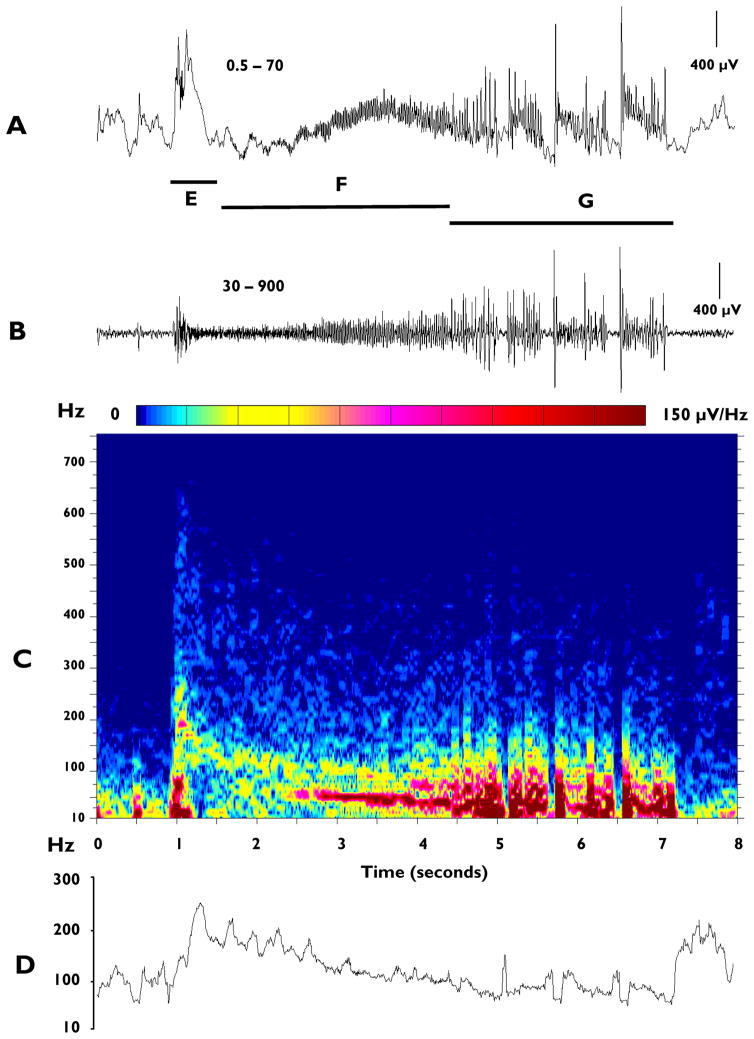

We next initiated spectral analyses of the ictal complexes to more fully describe these events. Figure 2A shows an example of the raw EEG tracing (LA electrode, filtered 0.5 – 70 Hz) of a seizure associated with a spasm, while Panel B shows the same EEG signal filtered at 30–900 Hz. The corresponding compressed spectral contour array is shown in Panel C. Changes in the average frequency over time are shown in Panel D and compiled from data in C. This is the same ictal event illustrated in Figure 1. In this example, the initial ictal event, corresponding approximately to the onset of the slow-wave complex seen in conventional EEG (indicated by horizontal bar labeled ‘E’), is characterized by the simultaneous occurrence of multiple bands (visible in the spectral array) of discrete HF components with typical durations of 100–300 msecs. Frequency components up to approximately 700 Hz have been recorded, although in most of the seizures analyzed the maximum frequency was below 600 Hz. During the subsequent portion of the ictal event, including the period of the electrodecrement (indicated by horizontal bar labeled ‘F’), nearly continuous runs of HF oscillations continue to occur. Initially these oscillations are lower in amplitude than the preceding initial burst at onset, but gradually increase with time. The corresponding spectral array (Figure 2C) reveals that coincident with the gradual increase of amplitude during the electrodecremental period there is a gradual loss in intensity of the highest frequency components that were present at seizure onset (i.e., greater than approximately 200 Hz), and a progressive increase in the intensity of the components below 200 Hz. This is further supported by analyzing the average frequency in Panel D. This pattern has been observed in the majority of the more than 660 seizures analyzed. In some cases, ictal events are terminated by repetitive spike/sharp wave complexes (indicated by horizontal bar labeled ‘G’) which may occur for several seconds. These events are associated with bursts of high frequency activity with components up to approximately 300 – 400 Hz and reminiscent of those seen at the onset of seizures.

Figure 2.

Analysis of an ictal EEG event recorded with electrode LA and associated with a behavioral spasm: A: 8-sec conventional tracing filtered 0.5–70 Hz. Lines below trace demark: E - the approximate duration of the slow wave of the ictal event, F – the electrodecrement and G – spike and sharpwave complexes. B: EEG tracing as in A, but filtered at 30–900 Hz to emphasize HF components. C: Spectral analysis of recording in A, with time on the x axis, frequency on the y axis and relative intensity (μV/Hz) color coded (see color bar above the plot). D: Plot of average (mean) frequency based on data in C.

As reported previously, behavioral spasms or their ictal discharges were never observed in ACSF-infused control rats. Similarly, high frequency activity like that recorded during ictal events was not observed in these controls.

An analysis of the onset of ictal events

Spectral pattern variability between seizures and across cortical regions

Since HF oscillations may predict sites of seizure generation, we next pursued a more detailed analysis of the regional differences in HF activity in our animal model. While we initially hypothesized that tissue surrounding the infusion site might become hyperexcitable in a compensatory manner and could be the site of seizure generation, our initial analyses (e.g. Figure 1 and 2) suggested that this might not be the case since intense HF oscillations appeared to be more prominent contralateral to the infusion site.

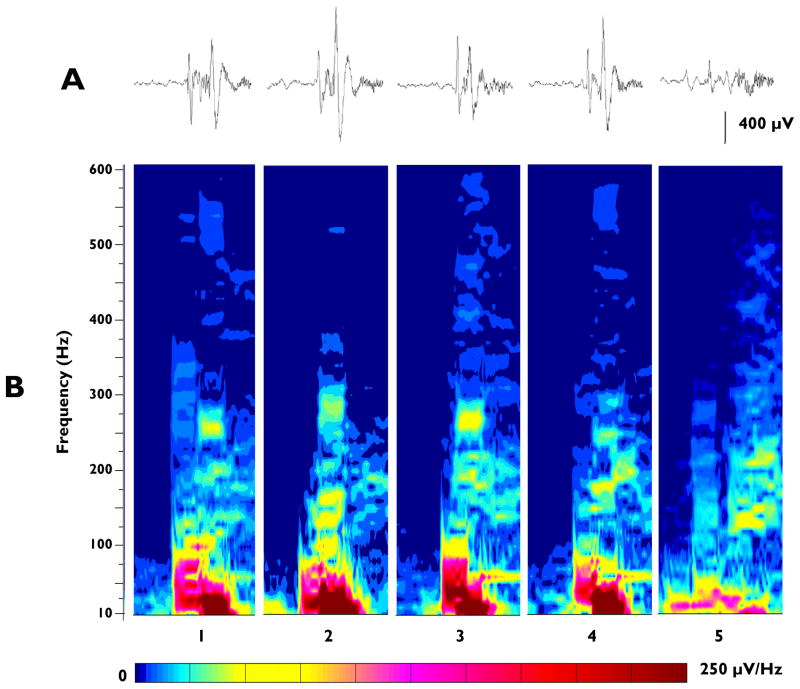

Consequently, we first examined the variability in high frequency activity across seizures at individual recording sites in a given animal. Our analysis of the initial 100–300 msec burst of HF EEG activity recorded from a specific cortical site at seizure onset showed expected similarities in terms of its amplitude and frequency composition from seizure to seizure in the same animal. This is illustrated in Figure 3, where the spectral patterns at the onsets of 5 consecutive seizures associated with spasms are compared. All 5 samples were recorded from the LA electrode site of the same animal on the same day. The raw recordings of the 5 seizures (Figure 3A) were comparable and could even be considered stereotyped, however when the spectral patterns were quantified the finer details of the frequency components differed from seizure to seizure (Figure 3B). Intense components present in one seizure can be of lower intensity in another. For example, the intense component at approximately 275 Hz in seizure 3 is also evident in seizure 1, but is of lower intensity in seizures 4 and 5.

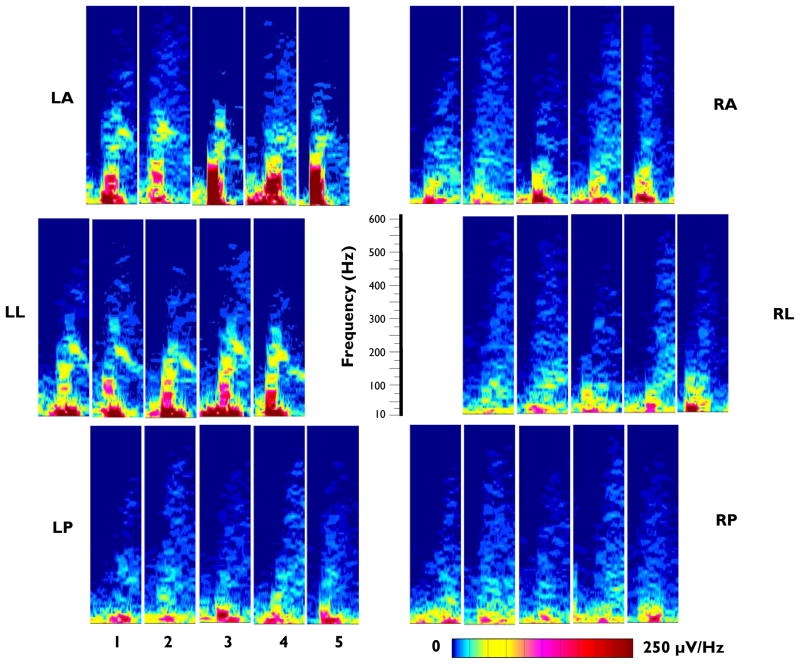

Figure 3.

Spectral plots of the EEG recorded from the LL electrode in a TTX-treated rat at the onset of 5 consecutive seizures associated with spasms. A: 500 msec raw EEG traces recorded at the onset of the 5 seizures (EEG band-pass filter 20–900 Hz). B: Spectral plots of the corresponding traces in Panel A. The width (horizontal axis) of each plot is 500msec. Relative spectral intensity is color-coded (see scale below spectral plots).

While the initial burst of HF EEG activity recorded from a specific cortical site at seizure onset is comparable in terms of the intensity and frequency distribution from seizure to seizure in the same animal, the pattern observed at one cortical site often differs dramatically from that observed at other sites. This is illustrated in Figure 4, for all 6 recording sites across 5 consecutive seizures recorded in one animal. Note that each site has a consistent pattern in terms of the overall frequency range and intensity pattern similar to that shown in Figure 3. However, there is a marked difference in the patterns observed in the 6 cortical sites, with those on the left side (contralateral to the TTX infusion site) exhibiting more intense spectral components over a wider frequency range, particularly in the frequency range above 100 Hz. This asymmetry is most pronounced in the anterior (LA vs. RA) and lateral (LL vs. RL) electrodes. The right and left posterior electrode recording sites (LP and RP) both show relatively low intensity patterns.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the spectral characteristics of the EEG at 6 recording sites: LA, RA, LL, RL, LP and RP. All recordings were referred to the cerebellar electrode. Spectral plots are of the ictal onset (500 msec samples) of 5 seizures in one TTX-treated rat. The order of seizure occurrence is left to right for each panel (labeled in LP panel). Relative spectral intensity is color-coded (see scale below RP panel). Frequency scale in center applies to all spectral plots. A band-pass filter of 20–900 Hz was employed for this analysis.

We next quantified the differences in the intensity of HF activity between recording sites in 5 consecutive seizures recorded in each of 4 experimental animals. The spectral components of the high frequency events (50 – 900 Hz) during the first 200 msec of the seizures were summed, normalized and the mean and SEM for each animal plotted in Figure 5A – 5D. These results clearly support the observations in Figure 4. In each animal, recordings from either the left anterior (LA) or left lateral (LL) electrodes had the highest intensity. This was markedly the case for recordings from animals in 5A, B and D and somewhat less so for 5C although in this animal the intensity of recordings from left anterior (LA) cortex were still substantially larger than those at any other site, which ranged from 35 – 65% of that recorded at LA. The results in Figure 5A–5D were summarized in Figure 5E by averaging the results for the 4 animals. The results clearly suggest that high frequency activity is most intense contralateral to the site of TTX infusion at the LA and LL recording sites. Spectral intensity recorded in site LA differed significantly from that recorded in RA, its homologous site in the infused cortex (p = 0.012). Recordings from sites LL and RL also differed statistically (p = 0.029) but LP and RP did not (p = 0.254).

The timing of seizure onset across cortical regions

The ictal EEG changes associated with spasms in the TTX model, like that observed in the human disorder, are generalized events, appearing simultaneously in all cortical regions when examined with conventional EEG recording speeds (for example see Figure 1B). As illustrated in Figure 6 with an expanded time-base and selective band-pass filtering, the onset of the higher frequency components (Figure 6B: 30–100 Hz and Figure 6C:100–900 Hz) appears to coincide approximately with the onset of the initial slow-wave seen at more conventional EEG settings (Figure 6A: 0.5–30 Hz filters). The vertical dashed line traversing all 3 panels indicates the onset of the seizure. Careful inspection of the HF onsets, particularly those in the 100–900 Hz range, reveals substantial variability in the onset times. This variability can be more readily appreciated by inspecting time-synchronized spectral plots of the activity in each EEG channel displayed at a greatly increased time-base, as illustrated in Figure 7. The seizure shown in Panel A was recorded at the LA site approximately 10 msec before onset at RA, and RA slightly precedes LL, followed at much later times at LP, RL and RP. In this example there is an approximately 80 msec time difference between the onset at the left anterior (LA) electrode and that at the right posterior (RP). Figure 7B shows another seizure which occurred later in the same animal and in which the onset pattern is different from that in Panel A, with both LL and LA preceding RA. These were followed by less intense HF oscillations at the other three recording sites. In this example there was an approximately 45 msec difference between the earliest onset in LL and the latest onset in RL.

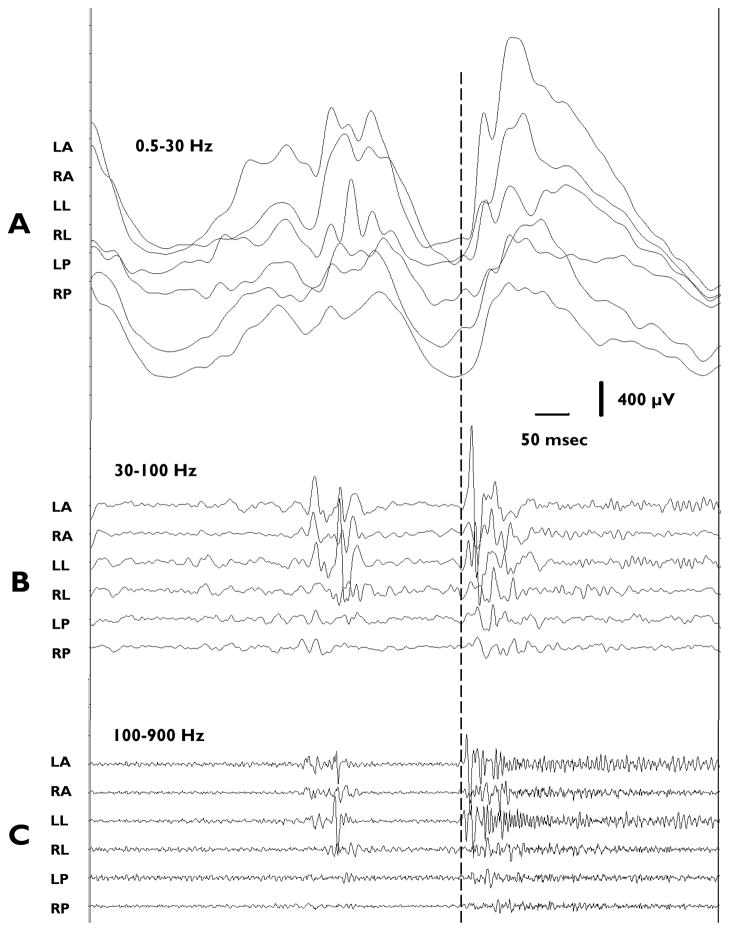

Figure 6.

Variations in the time of onset of ictal EEG activity at 6 cortical recording sites. Dashed line indicates time of onset of the seizure as revealed by analysis of video-EEG recordings. The same event was filtered at: 0.5–30 Hz in A, 30–100 Hz in B and 100–900 Hz in C. Calibrations apply to all Panels.

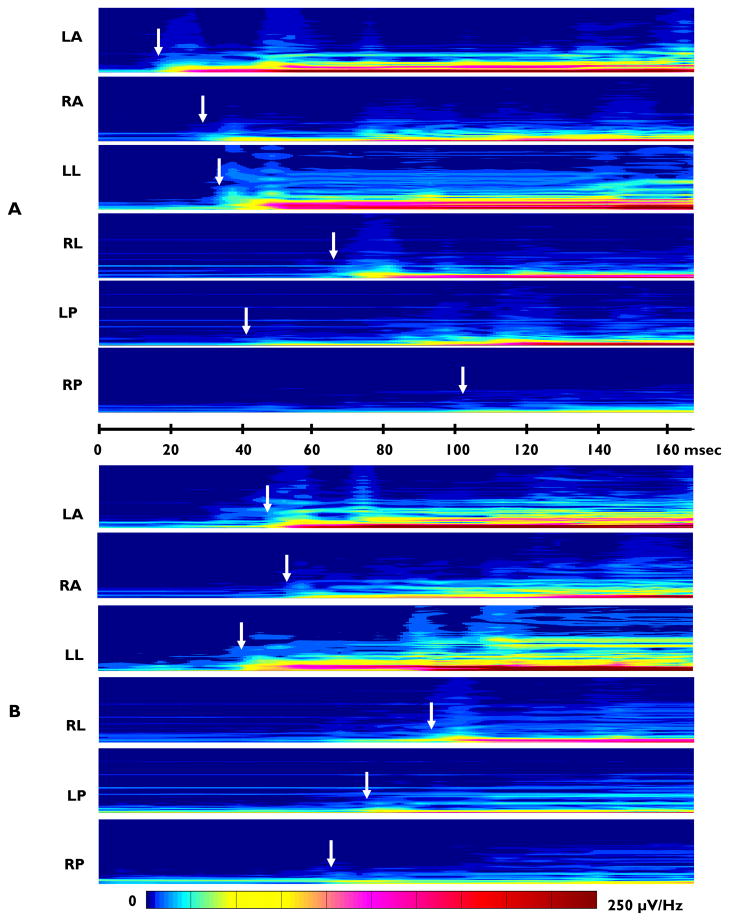

Figure 7.

Spectral plots comparing ictal EEG onset timing across cortical locations for 2 seizures. The ictal event in B occurred 3 hrs 24 min after the event in A. Recordings are 165 msec in duration. Filters 20–900 Hz. Vertical scale 10–600 Hz for each panel. A 60/120 Hz notch filter was also used. Relative spectral intensity is color-coded (see scale below). White arrows denote time of onset of the ictal event for each electrode recording site.

In order to quantify the degree of onset timing variability, 5 consecutive seizures associated with spasms were analyzed in each of 4 rats using the spectral analysis technique, together with selective band-pass filtering similar to that in Figure 6. The results are summarized in Table 1 and indicate some degree of variability in all 4 rats. No cortical site always led the seizure onset in any of the animals, but recordings by the left anterior (LA) and left lateral (LL) electrodes did so much more frequently than any other location. Seizures began first in either LA or LL in 14 of the 20 seizures analyzed in these 4 animals (70% of the time). Similarly, no cortical site consistently discharged last, but the RP did so more frequently (50% of the time) than any of the other locations. The time difference between the earliest and latest onsets ranged from 10 to 141 msecs (interpolated values) in the 20 seizures evaluated, with an average value of 72 msecs.

Comparison of high frequency EEG activity and high frequency EMG activity

The possibility that the HF activity reported here may represent contamination of the EEG signals by volume conducted EMG activity was examined in 3 animals. EMG electrodes were implanted in facial and neck musculature and these signals were compared to simultaneously recorded EEG activity during spasms. In all cases the onset of the EMG activity was significantly later than that of the EEG activity, and the EMG spectral composition was markedly different than that of the EEG. Consequently, it is highly unlikely that EMG activity contributes significantly to the HF activity recorded in the EEG channels.

DISCUSSION

The experiments reported here show that high frequency EEG activity occurs throughout ictal events in our animal model of infantile spasms. Although, as in the human condition, ictal events could vary in the finer details of their electrographic features, the pattern of HF activity was in general quite consistent between seizures in any given animal and similar across animals. Ictal events began with a burst of intense high frequency oscillations that typically lasted several hundred msec. Over the next several seconds of the ictal event, very high frequency activity (>200 Hz) continued but at gradually lower intensities as the amplitude of the lower frequency oscillations (<200 Hz) actually increased. Sometimes the ictal event would terminate with spike/sharp wave complexes and accompanying intense high frequency activity. Results also showed that the HF oscillations associated with ictal events were not generated uniformly across the cortex and regional differences were marked. We hypothesized at the outset of our experiments that seizures would arise near the TTX infusion site and that a compensatory “excitatory surround” might be produced by the chronic blockade of neuronal activity. Consequently, we anticipated that HF oscillations during seizures would be most prominent or even solely recorded by electrodes adjacent to the infusion site. However, our results clearly do not show this; instead more robust HF activity was routinely recorded in the contralateral hemisphere, and onset occurred at these sites for 70% of seizures.

Significance of ictal high frequency EEG activity

As noted in the Introduction, there have been several prior reports documenting the association of EEG activity in the 15 – 120 Hz range with seizure onset in human cases of infantile spasms. While there are significant differences in the results reported from these clinical studies, all reported seizure-related maximum frequency components that were less than we report here in the TTX model. However, none of the clinical studies were conducted using recording systems capable of detecting components higher than 300 Hz, and none made use of intracortical electrodes.

Our results suggest that the ictal events in infantile spasms may actually share previously unappreciated features with seizures in other types of epilepsy. We show that these ictal events begin with a burst of HF activity and that over time ( even during the period when an electrodecrement is recorded with traditional filter settings) high frequency oscillations persist. During this time, the highest frequency energy gradually diminishes as the amplitude of somewhat lower frequency oscillations increases. Similar temporal patterns of changing spectral energy associated with HF activity have been noted during seizures in other forms of epilepsy and have been referred to as “spectral chirps” (Schiff et al., 2000; Worrell et al., 2004) - where discharges of high frequency at onset are followed by a shift to lower frequencies. It is interesting to note that in models of other forms of epilepsy, very high frequency oscillations (e.g. fast ripples -250–600 Hz) have been thought to be generated by local networks of mutually excitatory and possibly electrical-coupled pyramidal cells and that the frequency of oscillation may be set by the firing pattern of inhibitory interneurons that are also a part of these local circuits.

Pathophysiological considerations

The first studies of our animal model showed that seizures could only be produced by chronic TTX infusion beginning early in postnatal life – on postnatal days 10 – 12 (Galvan et al., 2000). TTX is well known to block voltage dependent sodium channels and has been used routinely by many laboratories to block neuronal activity. In our case, the local infusion into right cortex was shown to produce a region that was essentially devoid of glucose metabolic activity as measured by 2-deoxyglucose autoradiography (Galvan et al., 2000). A more recent investigation showed that at least in some animals TTX infusion results in a localized decrease in cortical thickness – possibly reminiscent of a cortical dysplasia (Lee et al. 2007). One possible consequence of TTX infusion would be a compensatory increase in excitability – resulting either from chronic action potential blockade or a resulting focal brain malformation, or a combination of both. In this regard, it has been shown that blockade of neuronal activity by TTX in dissociated neuronal cultures results in enhanced neuronal excitability including increases in glutamatergic synaptic transmission once TTX is withdrawn (Turrigiano et al., 1998; Turrigiano and Nelson, 2004). While this is an interesting possibility, the fact that spasms occur while TTX is still being perfused into cortex argues against compensation within the infusion site itself as a mechanism for seizure generation. While it is possible and even likely that the tissue immediately adjacent to the infusion site compensates and becomes hyperexcitable in a manner akin to homeostatic plasticity (Galvan et al., 2003), our results show that fast activity is actually more prominent and seizure onset is more frequent contralateral to the site of TTX infusion. These findings suggest that activity blockade by TTX in one hemisphere may alter the development of the other hemisphere. The maturation of synaptic projections to and within the contralateral hemisphere would be possible mechanisms impacted by chronic TTX treatment. While we have no direct evidence that this is the case in our model, other studies suggest this can happen. Axons have been shown to cross the midline by postnatal day 3 and begin to branch extensively in their homotopic counterpart by postnatal day 5–6, while axon growth continues until the end of postnatal week 2 (Wang et al., 2007). However with time, many of these early-formed branches are thought to be pruned to leave the adult pattern of more restricted innervation (O’Leary et al., 1981). Since synapse selection is widely recognized to be an activity-dependent competitive process, it is possible that exuberant local circuit axons in contralateral cortex (Lowel and Singer, 1992; Singer, 1995), which would have normal firing properties, might be preserved by outcompeting comparatively silent axons and synapses projecting from neurons whose activity is suppressed. Whether such abnormal remodeling of axon collaterals occurs in the TTX model must await further study. But in this regard it is interesting to note that hyperconnected local circuits have been proposed to underlie the high frequency oscillations of fast ripples at least in temporal lobe epilepsy (Bragin et al., 2002a).

While there has been a general consensus in the past that infantile spasms may result from interactions between abnormal cortical and subcortical (including brainstem) neural networks (Chugani et al., 1992; Lado and Moshe, 2002; Dulac et al., 2002; Frost Jr. and Hrachovy, 2003), studies directly supporting this view are quite limited. Results from our experiments clearly suggest that neocortical networks contribute to the generation of spasms in the TTX model. However, at this time we can not rule out the possibility that the seizure activity is initiated from a subcortical site that triggers cortical activity. This concept is supported by the experiments of Curio (Curio, 2000) in which high frequency activity recorded from the somatosensory cortex was triggered by ascending influences from subcortical structures. Furthermore, it remains a possibility that chronic TTX infusion in some way selectively suppresses the ability of the infused cortex to generate HF oscillations and their presence contralaterally reflects a relatively normal response to a hypersynchronous subcortical drive.

Table 1.

Variability of ictal electrical activity onset times across cortical areas (Five seizures associated with spasms evaluated in each of 4 rats)

| Rat CV#1 | Rat CV#2* | Rat CS#2 ** | Rat CT#*** | Totals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Last | First | Last | First | Last | First | Last | First | Last | |

| Cortical Location | ||||||||||

| LA | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 1 |

| RA | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| LL | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 11 | 1 |

| RL | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| LP | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| RP | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 10 |

| Onset Time | ||||||||||

| Range (msec) | 27–141 | 45–88 | 10–83 | 63–120 | 0–141 | |||||

| Average (msec) | 77 | 70 | 52 | 90 | 72 | |||||

The upper portion of the table shows, for each of the 4 rats, the number of times each cortical site had the earliest (column labeled ‘First’) and latest (column labeled ‘Last’) onset of ictal activity during each of the 5 seizures. Ties for earliest or latest onset credited to all channels showing simultaneous onset.

The lower portion of the table shows the range and average amount by which the onsets differed across channels in each rat.

Unable to determine exact onset time in LP and RP for 2 of the 5 seizures.

Unable to determine exact onset time in RL, LP and RP for 3 of the 5 seizures.

Unable to determine exact onset time in RA, RL, LL, and RL for 1 of the 5 seizures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NINDS, The Vivian L. Smith Foundation and Questcor Pharmaceuticals

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- Bickford RG, Billinger TW, Fleming NI, Steward F. The compressed spectral array (CSA). a pictorial EEG. Proc San Diego Biomed Symp. 1972;11:365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Azizyan A, Almajano J, Wilson CL, Engel J., Jr Analysis of chronic seizure onsets after intrahippocampal kainic acid injection in freely moving rats. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1592–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Engel J, Jr, Wilson CL, Fried I, Buzsaki G. High-frequency oscillations in human brain. Hippocampus. 1999;9:137–142. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:2<137::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Mody I, Wilson CL, Engel J., Jr Local generation of fast ripples in epileptic brain. J Neurosci. 2002a;22:2012–2021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-02012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Wilson CL, Staba RJ, Reddick M, Fried I, Engel J., Jr Interictal high-frequency oscillations (80–500 Hz) in the human epileptic brain: entorhinal cortex. Ann Neurol. 2002b;52:407–415. doi: 10.1002/ana.10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugani HT, Shewmon DA, Sankar R, Chen BC, Phelps ME. Infantile spasms: II. Lenticular nuclei and brain stem activation on positron emission tomography. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:212–219. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curio G. Linking 600-Hz “spikelike” EEG/MEG wavelets (“sigma-bursts”) to cellular substrates: concepts and caveats. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;17:377–396. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac O, Soufflet C, Chiron C, Kaminska A. What is West syndrome? Int Rev Neurobiol. 2002;49:1–22. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(02)49003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Jr, Bragin A, Staba R, Mody I. High-frequency oscillations: what is normal and what is not? Epilepsia. 2009;50:598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JD, Jr, Hrachovy RA. Infantile Spasms. Boston: Kluber Academic Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan CD, Hrachovy RA, Smith KL, Swann JW. Blockade of neuronal activity during hippocampal development produces a chronic focal epilepsy in the rat. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2904–2916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02904.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan CD, Wenzel JH, Dineley KT, Lam TT, Schwartzkroin PA, Sweatt JD, Swann JW. Postsynaptic contributions to hippocampal network hyperexcitability induced by chronic activity blockade in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1861–1872. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Kobayashi K, Oka M, Yoshinaga H, Ohtsuka Y. Spectral characteristics of EEG gamma rhythms associated with epileptic spasms. Brain Dev. 2008;30:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirsch JD, Urrestarazu E, LeVan P, Olivier A, Dubeau F, Gotman J. High-frequency oscillations during human focal seizures. Brain. 2006;129:1593–1608. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Oka M, Akiyama T, Inoue T, Abiru K, Ogino T, Yoshinaga H, Ohtsuka Y, Oka E. Very fast rhythmic activity on scalp EEG associated with epileptic spasms. Epilepsia. 2004;45:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.45703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lado FA, Moshe SL. Role of subcortical structures in the pathogenesis of infantile spasms: what are possible subcortical mediators? Int Rev Neurobiol. 2002;49:115–140. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(02)49010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CL, Antalffy B, Frost JD, Jr, Hrachovy RA, Swann JW. Persistent Focal Neocortical Abnormalities in the TTX Model of Infantile Spasms. Epilepsia. 2007;48 (S6):295. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CL, Frost JD, Jr, Swann JW, Hrachovy RA. A New Animal Model of Infantile Spasms with Unprovoked Persistent Seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49:298–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Idiart MA. Storage of 7 +/− 2 short-term memories in oscillatory subcycles. Science. 1995;267:1512–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.7878473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas RR. The intrinsic electrophysiological properties of mammalian neurons: insights into central nervous system function. Science. 1988;242:1654–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.3059497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowel S, Singer W. Selection of intrinsic horizontal connections in the visual cortex by correlated neuronal activity. Science. 1992;255:209–212. doi: 10.1126/science.1372754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DD, Stanfield BB, Cowan WM. Evidence that the early postnatal restriction of the cells of origin of the callosal projection is due to the elimination of axonal collaterals rather than to the death of neurons. Brain Res. 1981;227:607–617. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(81)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzica F, Binelli S, Canafoglia L, Casazza M, Freri E, Granata T, Avanzini G, Franceschetti S. ICTAL EEG fast activity in West syndrome: from onset to outcome. Epilepsia. 2007;48:2101–2110. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzica F, Franceschetti S, Binelli S, Canafoglia L, Granata T, Avanzini G. Spectral properties of EEG fast activity ictal discharges associated with infantile spasms. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(98)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampp S, Stefan H. Fast activity as a surrogate marker of epileptic network function? Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:2111–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff SJ, Colella D, Jacyna GM, Hughes E, Creekmore JW, Marshall A, Bozek-Kuzmicki M, Benke G, Gaillard WD, Conry J, Weinstein SR. Brain chirps: spectrographic signatures of epileptic seizures. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:953–958. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer W. Development and plasticity of cortical processing architectures. Science. 1995;270:758–764. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Sakurada O, Shinohara M. The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem. 1977;28:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE. Infantile spasms: a critical review of emerging animal models. Epilepsy Curr. 2009;9:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2009.01299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Whittington MA, Buhl EH, LeBeau FE, Bibbig A, Boyd S, Cross H, Baldeweg T. A possible role for gap junctions in generation of very fast EEG oscillations preceding the onset of, and perhaps initiating, seizures. Epilepsia. 2001;42:153–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.26900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Dasai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391:845–846. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CL, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Zhou J, Yang XJ, Duan SM, Xiong ZQ, Ding YQ. Activity-dependent development of callosal projections in the somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11334–11342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3380-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell GA, Parish L, Cranstoun SD, Jonas R, Baltuch G, Litt B. High-frequency oscillations and seizure generation in neocortical epilepsy. Brain. 2004;127:1496–1506. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]