Abstract

Background

Although inpatient rehabilitation may enhance an individual’s functional ability after stroke, it is not known whether these improvements are accompanied by an increase in daily use of the arms and legs.

Objective

To determine the change in daily use of the upper and lower extremities of stroke patients during rehabilitation and to compare these values with that of community-dwelling older adults.

Methods

A total of 60 stroke patients underwent functional assessments and also wore 3 accelerometers for 3 consecutive weekdays on admission to rehabilitation and 3 weeks later prior to hospital discharge. The number of steps and upper-extremity activity counts were measured over the waking hours and during daily use for occupational therapy and physical therapy (PT) sessions. Healthy older adults (n = 40) also wore 3 accelerometers for 5 consecutive days.

Results

Stroke patients demonstrated a significant increase in mobility function, and this was accompanied by an increase in daily walking over the entire day as well as in PT. However, increases in daily walking were found predominantly in patients who were wheelchair users (and not walkers) at the time of admission. Control walking values (5202 steps) were more than 17 times that of stroke patients. Despite significant improvements in paretic hand function, no increase in daily use of the paretic or nonparetic hand was found over the entire day or in PT. Conclusions. A disparity between functional recovery and increases in daily use of the upper and lower extremities was found during inpatient stroke rehabilitation.

Keywords: accelerometers, physical activity, rehabilitation

Introduction

The most common symptom poststroke is hemiparesis of the upper and lower extremities contralateral to the brain lesion1. Therapies provided in the hospital such as physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) focus on reducing the motor impairments early after stroke while enhancing the individual’s functional ability. In light of the potential benefits of these therapies, in addition to the costly nature of inpatient rehabilitation, it is important to objectively quantify the amount of these activities performed by individuals who are undergoing rehabilitation.

It is well established that hundreds of repetitions of movement are required for brain plasticity to occur2,3. Observational analysis of typical stroke inpatient activities has provided useful information on the content of activities within therapy, as well as during non-structured time through the rest of the day. Lang et al. (2009)4 observed 312 inpatient and outpatient therapy sessions of PT or OT and reported on average 32 repetitions of upper extremity movement and 367 lower extremity steps per therapeutic session. Bernhardt et al. (2004)5 observed 58 acute stroke patients from 5 Australian hospitals between 8 am-5 pm for approximately one minute at 10 min intervals over 2 days and reported that these patients spent only 13% of the day involved in mobility activities. Esmonde et al. (1997)6 performed observations on 17 in-patients in subacute stroke rehabilitation and reported that they were not involved in structured therapy for two thirds of the 9 am-5 pm day and that for only half of these observations were they engaged in motor activities. De Wit et al. (2005)7 observed 160 in-patients with stroke between 7 am-5 pm and recorded observations at 10-minute intervals for four European stroke rehabilitation units (1800 observations at each of the four sites). The total time spent in therapeutic activities ranged from 1 hour per day to 2 hours and 46 minutes per day, of which 40% of this time was in PT sessions. The percentage of non-therapy time ranged from 72%–90% of the day.

Thus, the data from observational analyses suggest that the number of repetitions, as well as the amount of physical activity (PA) is low during inpatient stroke rehabilitation. The majority of these studies used observational recordings at interspersed sampling intervals and utilized a rater who subjectively categorized the activities. In contrast, instrumented monitoring of PA can provide continuous recording for a single session or even over several days to provide a more accurate quantification of activity. For example, Smith et al. (2008)8 used a Positional Activity Logger and found inpatients with stroke spent a median of 1.3 hours/day standing upright which was substantially less than the community group (5.5 hours). But the amount of daily-use of the extremities while positioned upright was not reported.

Accelerometers are a relatively new instrument to measure activity which have recently been shown to be a valid and reliable tool to objectively measure the amount of daily PA of individuals with stroke9. This technique can provide a continuous measure of daily-use, not only of the lower extremities9, but also of the upper extremities10. In addition, long recordings of accelerometer activity can provide a picture of daily-use of the upper and lower extremities both within therapy sessions, as well as during non-structured time.

As no previous studies have attempted to determine whether the amount of daily upper and lower extremity use increases over stroke rehabilitation, accelerometers are a reliable instrument to quantify this potential change in daily-use and are not limited by subjective observations. Hence, the first purpose of our study was to determine the change in daily-use of the upper and lower extremities of patients with stroke during subacute stroke rehabilitation. It is also pertinent to know how much activity stroke patients are undertaking when they are discharged home from the hospital and to compare these values to healthy older adults living independently in the community. Such a comparison would allow clinicians to know how much additional daily-use is required by their patients for community living. Thus, the second purpose was to compare the amount of daily-use of the upper and lower extremities of patients undergoing subacute stroke rehabilitation to that of older community dwelling adults.

Methods

This study was approved by the local university and hospitals ethics board and all participants provided informed consent form.

Population

Participants were consecutive adults admitted to two inpatient rehabilitation centers within 60 days of sustaining a stroke as confirmed by CT or MRI. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 19 years old, had a significant musculoskeletal condition within the last 6 months, neurological condition other than stroke or if they had communication or cognitive difficulties that prevented them from providing informed consent. When the patient could not speak English, we used a translator to assist with the assessment. In addition, a control sample of community-dwelling healthy older adults was recruited through advertisements posted in community and shopping centers, and via snowballing techniques. Inclusion criteria of the control group were right-handed as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory11, full use of the upper extremities and independent in activities of daily living. We selected right-handed individuals because up to 90% of the general population are right handed. Exclusion criteria were a neurological condition or significant musculoskeletal condition.

Instruments

Accelerometers (Actical™, Mini Mitter Co) were used to quantify daily upper and lower extremity use; one on each wrist to measure upper extremity movement and one accelerometer on the hip to measure lower extremity movements and steps walked. The accelerometer is small (28X27X10 mm), light (17g), waterproof, and sensitive to 0.05–2.0 G-force. It has a frequency range of 0.3–3 Hz, samples at 32 Hz, and then rectifies and integrates acceleration over 15 second epochs as activity counts. The Actical accelerometer detects acceleration in all 3 planes but is more sensitive in the vertical direction. When worn on the hip it has a valid step count function12. The intra-instrument and inter-instrument reliability of the Actical accelerometer was found to be superior to the Actigraph and RT3 accelerometers13. When worn on the hip, the Actical accelerometer has been found to be valid and reliable for detecting free-living PA in individuals with chronic stroke9. When worn on the wrist, the daily Actical accelerometer activity counts have been shown to correlate with hand dexterity (measured by the Box and Block Test) in older adults10. In addition, daily Actical wrist activity counts have been found to have moderate correlations to brain activation during a grip task in stroke patients14. Lastly, studies using other types of wrist accelerometers have reported moderate to strong correlations between accelerometer readings and self-report measures of arm activity (r=0.93)15 or upper extremity function (r=0.40–0.91)16,17.

A number of assessments were collected at baseline to provide a description of the subjects. General cognitive ability (Mini-Mental State Exam)18 was assessed and a screening test for unilateral visual neglect (BIT Star Cancellation Test)19 was administered (neglect was defined if less than 45/54 stars were identified20). Depressive symptoms were obtained using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale21, which is a reliable and valid screening tool for assessing depressive symptoms in individuals with stroke22.

Clinical assessments were used to determine the level of the motor and functional ability of the upper and lower extremities and were undertaken at both Assessment 1 (on admission) and Assessment 2 (3 weeks later). The Fugl-Meyer Motor assessment23 (upper extremity scale) was used to assess the motor impairment of the paretic upper extremity and its validity and reliability have been well established in stroke23,24. Scores range from 0 points (no active movement) to 60 points (full active movement). The Action Research Arm Test25 is a reliable and valid measure for function of the paretic upper extremity of individuals with stroke26 and measures the quality of movements such as grip, grasp, pinch tasks and gross movements. Scores range from 0 points (a non-functional hand) to 57 points (a fully functional hand). The Berg Balance Scale27 was administered to assess the ability to maintain balance while performing 14 functional tasks and is a reliable and valid measure of balance in stroke28. Scores range from 0 points (poor balance) to 56 points (excellent balance ability). Mobility was determined by using two walking tests: 10 m Walk Test29 (gait speed in m/sec over 10 m) and the Six Minute Walk Test (distance walked in m over 6 minutes)30. These measures are valid and reliable for use with individuals with stroke31. In addition, the functional ability of the patients performing basic activities of daily living was assessed using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM)32, which has been found to be reliable and valid when used with individuals with stroke.

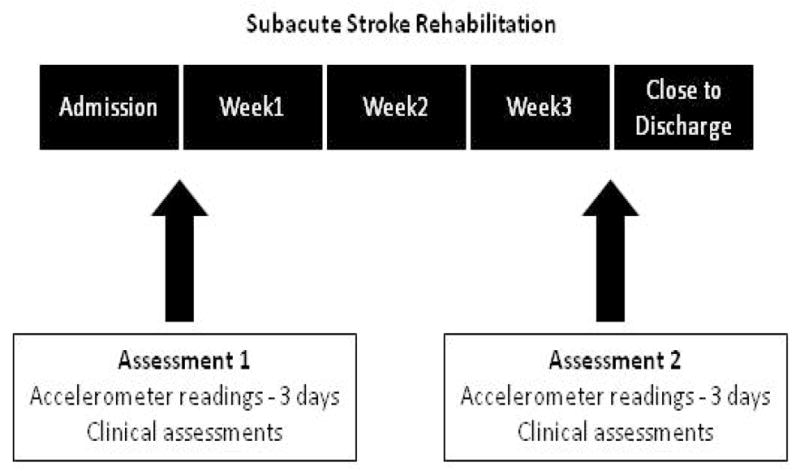

Procedure

Using triaxial accelerometers, the total amount of daily-use of the upper and lower extremities was measured in addition to the amount of daily-use performed during therapeutic OT and PT sessions. Measurements were undertaken over 3 days on admission to rehabilitation (assessment 1) and three weeks later, prior to discharge (assessment 2). Eligible stroke patients were approached by a site coordinator during the first week of their rehabilitation. Starting on the following Monday, patients were given 3 accelerometers to wear for 3 days. Patients were allowed to remove the accelerometers during the night. Once removed, the nursing staff assisted the patients to put on the accelerometers in the morning and the site coordinator visited the patients each day to ensure the accelerometers were worn in the correct manner. During this 3 day period, the patient’s therapists filled in a log regarding the start and end time of each PT and OT session. The accelerometers were removed on the following Friday and accelerometer readings were downloaded from 3 full days (Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday). The clinical assessments were then undertaken. Three weeks later, this procedure was repeated (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data collection of the in-patient sample during stroke rehabilitation

For both the upper and lower extremity activity, we calculated the mean daily-use (activity counts for the upper extremity and steps for the lower extremity divided by the 3 days) for 1) an entire day, 2) a PT session 3) an OT session and 4) daily-use not including the OT/PT sessions (total daily-use minus the OT/PT sessions). For the upper extremities, we eliminated the activity counts of arm swing while walking (defined as 5 consecutive steps or more in one epoch) so that our measure reflected goal directed hand usage.

Control subjects wore three accelerometers for 5 consecutive days. The mean daily total number of steps/day was calculated in addition to the right and left upper extremity activity counts. The activity counts were adjusted for the arm swing while walking in the same manner.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the demographic data in addition to the accelerometer readings were calculated. Paired t-tests were used to assess changes in the clinical measures between assessment 1 and 2. As patients unable to ambulate on admission may have different recovery, we divided the patients into two groups based on their admission walking ability (Walkers and Wheelchair-Users). Walkers were patients who were able to walk independently around the ward at admission. T-tests were utilized to assess the differences between the Walkers and the Wheelchair-Users for the clinical assessments. Since the distribution for the accelerometer readings was not normal, non-parametric statistics were used; the median and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for the daily-use and Wilcoxon tests were used to assess changes in daily accelerometer use between assessment 1 and 2. This statistical procedure was applied to assess 1) steps within therapy; 2) steps outside of therapy; 3) upper extremity activity counts within therapy; and 4) upper extremity activity counts outside of therapy. Wilcoxon tests were also used to assess changes in daily-use between assessment 1 and 2 for the subgroups (Walkers and Wheelchair-Users). SPSS (version 17.0) software was used to analyze the data.

Results

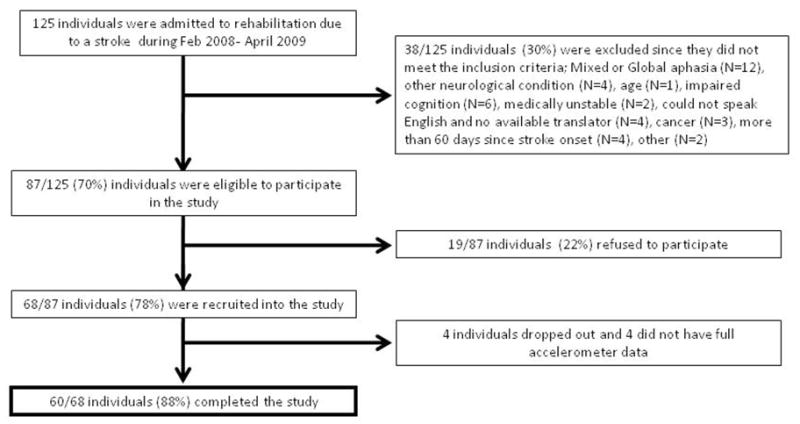

One hundred and twenty five patients were admitted to two rehabilitation centers due to a stroke from February 2008 to April 2009. Of these, 19 subjects declined to participate in the study (mean age 73.4±9.0 years, 62% males), 68 adults were eligible and agreed to participate (mean age 61.6±13.3 years, 65% males), however four patients (mean age 73.2±11.7, 1 male and 3 females) dropped out of the study before completing assessment 2 and four subjects (mean age 72.2±4) were excluded since they did not have full accelerometer data (See Figure 2 for CONSORT flow diagram and Table 1 for subject description). In addition, 40 healthy older adults (20 men and 20 women) were recruited to participate in the study (mean age 71.3±3.8).

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram of recruitment to the study

Table 1.

Demographic, stroke and clinical information [mean (SD)] of the total study sample, as well as divided into Walkers (N=27) and Wheelchair Users (N=33) on admission.

| All patients | Walkers | Wheelchair users | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=60 | N=27 | N=33 | ||

| Demographic and Stroke information | Age | 61.0 (13.3) | 64.3 (13.4) | 58.2 (12.8) |

| Days since the stroke | 33.4 (20.7) | 33.3 (19.2) | 33.5 (22.1) | |

| Years of education | 13.5 (4.3) | 14.1 (4.5) | 13.0 (4.1) | |

| MMSE (0–30) | 26.9 (3.3) | 26.5 (2.9) | 27.1 (3.6) | |

| FIM (18–126) | 91.4 (16.7) | 99.7 (14.8) | 84.6 (15.3) | |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | 8.5 (6.1) | 6.7 (5.8) | 10.1 (6.0) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender (M/F) | 41/19 (68/32) | 18/9 (67/33) | 23/10 (70/30) | |

| Side of stroke (R/L) | 33/27 (55/45) | 16/11 (59/41) | 18/15 (54/46) | |

| Stroke (first/recurrent) | 54/6 (90/10) | 25/2 (93/7) | 29/4 (88/12) | |

| Type of stroke (ischemic/hemorrhagic) | 49/11 (82/18) | 24/3 (89/11) | 25/8 (76/24) | |

| Dominant hand affected (Y/N) | 32/28 (53/47) | 13/14 (48/52) | 19/14 (58/42) | |

| Neglect (Y/N) | 7/53 (12/88) | 4/23 (15/85) | 3/30 (9/91) |

Twenty seven of the 60 patients with stroke were walking independently around the ward on Assessment 1 (Walkers) while 33 patients were using a wheelchair (Wheelchair-Users). On Assessment 2, 39% of the Wheelchair-Users on Assessment 1 had progressed to walking independently around the ward. On Assessment 1, the scores for all of the assessments of the Walkers were significantly higher compared to the Wheelchair-Users (Table 2). The Walkers were significantly better functioning in basic activities of daily living (assessed by the FIM) (t(59)=3.8, p<0.001), had significantly better hand function (assessed by the ARAT) [t(59)=3.5, p=0.001] and walking ability (assessed by the 6MWT) [t(59)=2.8, p=0.007]. The Walkers also reported less depressive symptoms compared to the Wheelchair-Users (see Table 1) (t(59)=−2.0. p=0.04). However there were no significant differences between the groups for age, days since stroke, number of years of education and function of the non-paretic upper extremity (assessed by the Box and Blocks Test).

Table 2.

The clinical assessments administered on Assessment 1 and 2 for the total study sample, as well as the Walkers and Wheelchair Users

| Clinical Assessments | All patients (N=60) | Differences between Assessment 1 and Assessment 2 | Walkers (N=27) | Wheelchair users (N=33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | Paired t-test | Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | |

| FMA (0–60) | 40.3 (19.7) | 44.8 (19.3) | t(59)=−2.9 p=0.005 |

49.1 (13.5) | 50.8 (14.3) | 34.1 (21.0) | 40.1 (21.6) |

| ARAT (0–57) | 32.5 (22.8) | 39.5 (21.8) | t(59)=−4.7 p<0.001 |

43.1 (18.4) | 46.5 (16.4) | 25.2 (22.9) | 34.1 (24.2) |

| BBS (0–56) | 32.6 (18.1) | 42.8 (14.5) | t(59)=−6.4 p<0.001 |

38.3 (16.7) | 46.4 (10.6) | 28.2 (18.4) | 39.9 (16.6) |

| Gait speed (m/sec) | 0.44 (0.5) | 0.84 (0.6) | t(59)=−4.8 p<0.001 |

0.7 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.5) |

| 6MWT (meters) | 156.6 (196.8) | 273.1 (205.5) | t(46)= −4.8 p<0.001 |

190.8 (214.0) | 311.0 (216.9) | 59.0 (125.0) | 241.6 (189.2) |

| FIM (18–126) | 91.0 (15.9) | 102.2 (14.9) | t(54)=−7.6 p<0.001 |

99.7 (14.8) | 104.4 (14.0) | 84.6 (15.3) | 100.3 (14.3) |

FMA – The Fugl-Meyer Motor Assessment

ARAT – the Action Research Arm Test

BBS- Berg Balance Scale

6MWT- six minutes walk test

FIM – Functional Independence Measure

As expected, the motor and functional abilities of the upper and lower extremities of the 60 stroke patients improved significantly over the three week period from Assessment 1 to Assessment 2 (See Table 2). When each group (Walkers and Wheelchair-Users) were assessed individually, the FMA score of the paretic hand of the Walkers was the only measure that did not show significant improvement from Assessment 1 to 2.

In general, a significant increase in the median values of the steps/day was seen (Table 3), however these values were very low. For example, the 60 stroke patients walked a median of 176 steps on Assessment 1 over an entire day and increased their steps significantly by 72% to a median of 302 steps/day on Assessment 2 (Table 3) (z=−2.2, p=0.02). Control values (median of 5202 steps) were statistically greater (17 times more) than the values of that of stroke patients close to discharge (z=−6.6, p<.001). Walking during therapeutic sessions (combined OT and PT steps) accounted for 12% and 26% of the steps recorded over the entire day on Assessment 1 and Assessment 2, respectively.

Table 3.

The median (IQR) number of steps walked by the healthy older adults, the total sample of stroke patients (N=60), and the stroke subgroups for the Walkers (N=27) and the Wheelchair users (N=33) on Assessment 1 and Assessment 2.

| Healthy older adults (N=40) | All stroke patients (N=60) | Differences between assessments | Walkers (N=27) | Wheelchair users (N=33) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | Wilcoxon Test | Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | ||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Median total per day | 5202 (3548–6333) | 176 (78–1891) | 302 (96–2315) | z=−2.2, p=0.02 | 306 (82–3095) | 1423 (178–3183) | 143 (71–386) | 283* (80–1650) |

| During OT session | - | 9 (2–65) | 16 (0–103) | NS | 17 (0–196) | 93 (0–264) | 6 (2–24) | 12 (0–74) |

| During PT session | - | 12 (3–88) | 63 (3–319) | z=−2.1, p=0.03 | 66 (6–658) | 173 (8–499) | 6 (1–33) | 16** (2–240) |

| Total per day minus OT and PT | - | 155 | 223 | 223 | 1157 | 131 | 255 | |

Differences between Assessment 1 and 2 for Wheelchair Users-

z=−2.1, p=0.04;

z=−2.4, p=0.01

The median number of steps walked by all of the patients during PT increased significantly from 12 to 63 steps per session over the three week period (z=−2.1, p=0.03), however, this likely constituted only a few additional minutes of walking over the session. The steps taken during the OT sessions did not differ significantly from Assessment 1 (median of 9 steps) to Assessment 2 (16 steps). A significant increase from a median of 143 to 283 steps/day by the Wheelchair-Users was found (z=−2.1, p=0.04). The Walkers on the other hand were not found to significantly increase the number of steps walked per day or during therapy sessions.

The daily-use of the paretic upper extremity on Assessment 2 was very similar to the daily-use measured on Assessment 1 (Table 4). The right and left upper extremity values of the control group (all right hand dominant) were similar with only a 14% difference between sides. On Assessment 2 the daily-use of the paretic upper extremity was significantly lower than the daily-use of both the right (z=−6.8, p<.001) and the left hand (z=−5.9, p<.001) of the healthy controls, but the daily-use of the non-paretic upper extremity was not significantly different to the daily-use of either hands of the healthy controls.

Table 4.

The median (IQR) daily use (activity counts) of the paretic and non-paretic upper extremity (Assessment 1 and Assessment 2) of the stroke patients compared to the Right and Left hands of the healthy controls.

| Healthy older adults (N=40) | All stroke patients (N=60) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | |||||

| Right hand | Left hand | Paretic | Non-paretic | Paretic | Non-paretic | |

| Median total per day | 184761 (131523–241819) | 159698 (107826–217489) | 35734 (18167–84238) | 147500 (90477–224835) | 41541 (19340–105980) | 164875 (95287–212920) |

| During OT sessions | 1862 (840–4661) | 6754 (3411–13314) | 2411* (635–6848) | 7750 (5027–12770) | ||

| During PT sessions | 3347 (1425–5049) | 6566 (3948–10834) | 2744 (927–5960) | 7835 (4559–12163) | ||

| Total per day minus OT and PT | 30525 | 134180 | 36386 | 149290 | ||

Difference between Assessment 1 and Assessment 2 z= −1.9, p=0.04

Upper extremity daily-use during therapeutic sessions (PT and OT combined) accounted for 14% and 12% of the use recorded over the entire day on Assessment 1 and Assessment 2, respectively (Table 4). Daily-use of the paretic upper extremity in PT sessions decreased by 18% from Assessment 1 to Assessment 2 and but this was not statistically different. There was a significant increase over the three weeks for paretic upper extremity daily-use during OT from a median of 1862 to 2411 activity counts (z=−1.9, p=0.04).

The daily-use of the non-paretic upper extremity was about 4 times more than the daily-use of the paretic upper extremity at both Assessment 1 and 2. The paretic upper extremity activity counts were one-third to one-half of the values of the non-paretic upper extremity during the therapy sessions.

Discussion

Our findings partially supported the hypothesis that daily-use of the lower extremity increases over in-patient stroke rehabilitation. However, our results do not support the hypothesis that daily-use of the upper extremity increases over inpatient stroke rehabilitation.

Patients who could already walk on admission (albeit slowly at 0.7 m/sec) did not increase the daily practice of their walking over the three weeks during PT, OT or during the rest of the day. During the PT sessions, all 60 patients walked a median of 63 steps per session near discharge, while the Walker subgroup walked a median of 173 steps. This number of steps would constitute only a few minutes of daily ambulatory exercise and would be insufficient for optimizing gait recovery, inducing positive changes in brain plasticity or generating a cardiovascular training effect.

Our findings supported the second hypothesis that the amount of daily-use of upper and lower extremities of the older community dwelling adults was substantially higher compared to daily-use of the stroke patients at discharge to the community. The median steps/day (5202) of our healthy controls fell within the expected range from population-based studies of older adults33. Most investigators consider the original recommendation of 10,000 steps/day to be unrealistically high especially for older adults34, 35. Several investigators have suggested that older adults in their seventies should strive for 7000–8000 steps/day for health benefits34–36 while Tudor-Locket et al.37 classified those walking less than 5000 steps/day as sedentary. Nevertheless, our patients with stroke are far below the steps/day that are likely required for health benefits, and for coping with the everyday needs of independent community living.

Although the non-paretic upper extremity activity counts (164,875) approached values of the right and left hands of healthy older adults (184761 and 159698 activity counts), the paretic upper extremity counts were only 25% of the non-paretic side. Since individuals undergoing rehabilitation are encouraged to be independent in daily activities, it is evident that they are mainly using their non-paretic hand to do so. In an attempt to explain the limited hand usage post-hoc, we examined whether having a dominant versus non dominant hand affected following stroke influenced paretic hand daily-use, but no significant effects were found.

The discrepancy between improvements in function and increases in PA participation can be framed within the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) model39. The gap between the recovery of capacity (in our case, clinical measures of impairment and function) and the very limited improvement in performance (in our case, daily-use of the upper and lower extremities) provides a useful guide as to what can be done to improve performance.

Outside of the PT/OT therapy sessions, the institutional setting may not be conducive to patients undertaking PA or exercise outside of their regular therapeutic sessions39. Space or exercise equipment may not be available and may restrict opportunities for walking or upper extremity exercise. In addition, individuals may not want to undertake exercise due to fatigue, low self-efficacy or learned non-use of the upper extremity40,41. In some cases, patients may not be able or safe to undertake PA without supervision due to impaired cognition, impaired balance, or impulsive behaviour. Furthermore, patients and their families may lack awareness of the activities they could be participating outside of therapy sessions.

Attempts have been made to increase the amount of physical activity outside of formal therapy time by using pedometers42, implementation of a home-work based exercise program43, and by using inexpensive interactive video games such as the Nintendo Wii system48.

Limitations

Although the Actical Accelerometer is superior to most pedometers which do not record any steps when individuals walk at slower speeds, this accelerometer underestimates steps at slower speeds [7% at walking speeds of 0.83 m/s] 12. For the Walkers subgroup who progressed from 0.7 m/s to 1.1 m/s, there is probably minimal underestimation but for the Wheelchair-Users who progressed from 0.2 to 0.6 m/s, the underestimation could potentially be greater. Since they are not independent in walking, there are not many steps to underestimate for this subgroup. In addition, we based our measure of lower extremity PA on steps which would capture activity during walking, stepping or transfers, but would not capture tasks such as stationary cycling, or leg exercises while supine or sitting. More so, for the upper extremity we cannot determine what specific activities are done when the movement is registered however, the Actical is sensitive to typical upper extremity movements (reaching, bringing hand to mouth). We have assumed that the arm activity counts primarily represent functional, purposeful movements. Although we have removed any arm swing from the arm activity counts, we cannot discount that other non-purposeful movements have been recorded by the accelerometer. Despite this fact, we feel that the accelerometers do provide a measure of use in ones environment as opposed to standardized clinical measures. The adults who declined to participate in the study were approximately ten years older than the study sample, which might point to selection bias. More so, the control group were approximately ten years older and included a smaller percentage of men compared to the study group. Despite the older age, the adults in the control group demonstrated substantially higher activity levels compared to the in-patients.

In conclusion, this is the first study that quantified the change in daily-use of the extremities during subacute rehabilitation. Daily-use of the upper and lower extremities was low with little change over stroke rehabilitation despite significant improvement on the clinical measures. These quantitative values will inform other investigators who attempt to increase daily-use through innovative interventions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of BC Medical Services Foundation (BCM08–0098 to J.J.E. and D.R.), postdoctoral funding (D.R.) from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Canadian Stroke Network, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)/Rx&D Collaborative Research Program with AstraZeneca Canada Inc., and career scientist awards (J.J.E.) from CIHR (MSH–63617) and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Teasell R, Bayona N, Heitzner J. The Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation (EBRSR) reviews current practices in stroke rehabilitation 2008. Clinical Consequences of Stroke. Downloaded on July 22nd 2010 from URL: http://www.ebrsr.com/uploads/Module_2_clinical_consequences_final.pdf.

- 2.Nudo RJ, Wise BM, SiFuentes F, Milliken GW. Neural substrates for the effects of rehabilitative training on motor recovery after ischemic infarct. Science. 1996;272:1791–1794. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd L, Winstein C. Explicit information interferes with implicit motor learning of both continuous and discrete movement tasks after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2006;30:46–57. doi: 10.1097/01.npt.0000282566.48050.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang CE, MacDonald JR, Reisman DS, et al. Observation of amounts of movement practice provided during stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1692–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Donnan G. Inactive and alone; physical activity within the first 14 days of acute stroke unit care. Stroke. 2004;35:1005–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000120727.40792.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esmonde T, McGinley J, Wittwer J, Goldie P, Martin C. Stroke rehabilitation: Patients activity during non-therapy time. Aust J Physiother. 1997;43:43–51. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Wit L, Putman K, Dejaeger E, et al. Use of time by stroke patients; A comparison of four European rehabilitation centers. Stroke. 2005;36:1977–1983. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177871.59003.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith P, Galea M, Woodward M, Said C, Dorevitch M. Physical activity by elderly patients undergoing inpatient rehabilitation is low: an observational study. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:209–213. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(08)70028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rand D, Eng JJ, Tang P, Jeng J, Hung C. How Active Are People With Stroke? Use of Accelerometers to Assess Physical Activity. Stroke. 2009;40:163–168. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.523621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rand D, Eng JJ. Arm–Hand Use in Healthy Older Adults. AJOT. 2010;64:877–885. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2010.09043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esliger DW, Probert A, Gorber SC, Bryan S, Laviolette M, Tremblay MS. Validity of the Actical accelerometer step-count function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1200–1204. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3804ec4e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esliger DW, Tremblay MS. Technical reliability assessment of three accelerometer models in a mechanical setup. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:2173–2181. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000239394.55461.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokotilo KJ, Eng JJ, McKeown MJ, Boyd LA. Greater activation of secondary motor areas is related to less arm use after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24:78–87. doi: 10.1177/1545968309345269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uswatte G, Miltner WH, Foo B, Varma M, Moran S, Taub E. Objective measurement of functional upper-extremity movement using accelerometer recordings transformed with a threshold filter. Stroke. 2000;31:662–667. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uswatte G, Taub E, Morris D, Vignolo M, McCulloch K. Reliability and validity of the upper-extremity Motor Activity Log-14 for measuring real-world arm use. Stroke. 2005;36:2493–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185928.90848.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang CE, Wagner JM, Edwards DF, Dromerick AW. Upper extremity use in people with hemiparesis in the first few weeks after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31:56–63. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e31806748bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson B, Cockburn J, Halligan P. Development of a behavioral test of visuospatial neglect. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsh NV, Kersel DA. Screening tests for visual neglect following stroke. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 1993;3:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinar D, Gross CR, Price TR, Banko M, Bolduc PL, Robinson RG. Screening for depression in stroke patients: the reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Stroke. 1986;17:241–245. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jääskö L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7:13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh YW, Wu CY, Lin KC, Chang YF, Chen CL, Liu JS. Responsiveness and validity of three outcome measures of motor function after stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2009;40:1386–1391. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.530584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyle RC. A performance test for assessment of upper limb function in physical rehabilitation treatment and research. Int J Rehabil Res. 1981;4:483–492. doi: 10.1097/00004356-198112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang CE, Wagner JM, Dromerick AW, Edwards DF. Measurement of upper-extremity function early after stroke: properties of the action research arm test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1605–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg K, Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI, Gayton D. Measuring balance in the elderly: Preliminary development of an instrument. Physio Canada. 1989;41:304–311. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blum L, Korner-Bitensky N. Usefulness of the Berg Balance Scale in stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2008;88:559–566. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salbach NM, Mayo NE, Higgins J, Ahmed S, Finch LE, Richards CL. Responsiveness and predictability of gait speed and other disability measures in acute stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1204–1212. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.24907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eng JJ, Chu KS, Dawson AS, Kim CM, Hepburn KE. Functional walk tests in individuals with stroke: relation to perceived exertion and myocardial exertion. Stroke. 2002;33:756–761. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.104195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granger CV. The emerging science of functional assessment: our tool for outcomes analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tudor-Locke C, Hart TL, Washington TL. Expected values for pedometer-determined physical activity in older populations. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aoyagi Y, Park H, Watanabe E, Park S, Shephard RJ. Habitual physical activity and physical fitness in older Japanese adults: the Nakanojo Study. Gerontology. 2009;55:523–531. doi: 10.1159/000236326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tudor-Locke C, Hatano Y, Pangrazi RP, Kang M. Revisiting “how many steps are enough?”. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:S537–S543. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c7133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe DA, Kemble CD, Robinson TS, Mahar MT. Daily walking in older adults: day-today variability and criterion-referenced validity of total daily step counts. J Phys Act Health. 2007;4:434–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tudor-Locke C, Ham SA. Walking behaviors reported in the American Time Use Survey 2003–2005. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5:633–647. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ada L, Mackey F, Heard R, Roger A. Stroke rehabilitation: Does the therapy area provide a physical challenge? Aust J Physiother. 1999;45:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolf SL, Lecraw DE, Barton LA, Jann BB. Forced use of hemiplegic upper extremities to reverse the effect of learned nonuse among chronic stroke & head-injured patients. Exp Neurol. 1989;104:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(89)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taub E, Miller NE, Novack TA, et al. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;21:298, 2296–304. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris JE, Eng JJ, Miller WC, Dawson AS. A self-administered Graded Repetitive Arm Supplementary Program (GRASP) improves arm function during inpatient stroke rehabilitation: a multi-site randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2009;40:2123–2128. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.544585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saposnik G, Teasell R, Mamdani M, et al. Stroke Outcome Research Canada (SORCan) Working Group. Effectiveness of virtual reality using wii gaming technology in stroke rehabilitation: a pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle. Stroke. 2010;41:1477–1484. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]