Abstract

The authors present the clinical case of an 87-year-old Caucasian male admitted to the emergency room with hematemesis. He had a history of intermittent dysphagia during the previous month. Endoscopic evaluation revealed an eccentric, soft esophageal lesion located 25-35 cm from the incisors, which appeared as a protrusion of the esophagus wall, with active bleeding. Biopsies were acquired. Tissue evaluation was compatible with a melanoma. After excluding other sites of primary neoplasm, the definitive diagnosis of Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Esophagus (PMME) was made. The patient developed a hospital-acquired respiratory infection and died before tumor-directed treatment could begin. Primary malignant melanoma represents only 0.1% to 0.2% of all esophageal malignant tumors. Risk factors for PMME are not defined. A higher incidence of PMME has been described in Japan. Dysphagia, predominantly for solids, is the most frequent symptom at presentation. Retrosternal or epigastric discomfort or pain, melena or hematemesis have also been described. The characteristic endoscopic finding of PMME is as a polypoid lesion, with variable size, usually pigmented. The neoplasm occurs in the lower two-thirds of the esophagus in 86% of cases. PMME metastasizes via hematogenic and lymphatic pathways. At diagnosis, 50% of the patients present with distant metastases to the liver, the mediastinum, the lungs and the brain. When possible, surgery (curative or palliative), is the preferential method of treatment. There are some reports in the literature where chemotherapy, chemohormonotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy, with or without surgery, were used with variable efficacy. The prognosis is poor; the mean survival after surgery is less than 15 mo.

Keywords: Esophagus, Melanoma, Esophagoscopy, Upper gastrointestinal tract, Neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus (PMME) is a rare neoplasm. Only 0.1% to 0.2% of all esophageal malignant tumors are attributed to PMME and only 0.5% of all noncutaneous melanomas are found in the esophagus[1].

Although PMME was first reported in 1906[2] and confirmed with histological evidence in 1952[3], the diagnosis remained controversial until 1963 when the presence of benign melanocytes within the esophageal mucosa was demonstrated[4]. This observation was confirmed later in two other studies[5,6].

Risk factors are not yet defined but esophageal melanosis has been indicated as predisposing factor[6-8].

PMME is more common in men between de 6th and 7th decades[1,9,10]. Cases have been described at young ages[11,12]. A higher incidence has been described in Japan[1,9].

Symptoms are usually present for less than 3 mo. Dysphagia is the most frequent complain at presentation but retrosternal or epigastric discomfort or pain are also common. Hematemesis or melena are less frequent[1].

A polypoid, pigmented lesion in the lower two-thirds of the esophagus is the typical endoscopic finding[10]. Less frequently they are non-pigmented, but melanin can be identified in histological examination in a large proportion of those cases[1,9,13], and the true incidence of amelanotic melanoma of the esophagus is less than 2%[14].

Thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT), barium swallow examination and endoscopic ultrasonography are useful as staging methods[15-18].

Most PMME are diagnosed at advances stages of the disease[10]. Although there is not a formal recommendation, surgery is the preferential method of treatment but the prognosis remains poor.

The authors present a case of PMME and review the literature.

CASE REPORT

An 87-year-old Caucasian male, without relevant or previously known health problems, was brought to our emergency room with hematemesis. He had a history of intermittent dysphagia during the previous month. After hemodynamic stabilization, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed revealing an eccentric, soft lesion located 25-35 cm from the incisors, which appeared as a protrusion of the esophagus wall, with active bleeding and numerous clots. A CT scan was performed to characterize the nature of the lesion. The CT identified a solid enhancing mass with soft tissue attenuation, extending above the aortic arch and without any imaging signs of aortic invasion (Figure 1). No apparent pulmonary, hepatic or mediastinal nodes or adenopathies were identified. After excluding the possibilities of an aortic aneurysm or aorto-esophageal fistula, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was repeated with endoscopic hemostasis, administering 10 mL of adrenaline (1:10 000). The next day an endoscopic review was performed (Figure 2) and biopsies were acquired. Histological examination revealed “tissue infiltrated with crowded cells, most of them without visible cytoplasm (when visible, it contained a brown pigment that stained black with Fontana Masson technique) and hyperchromatic, rounded nuclei” (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical findings included positive vimentin, protein S-100 and HMB-45 staining and negative keratins (MNF, LP 34, CAM 5.2) and LCA (Figure 3B). The patient was observed by the dermatology and ophthalmology departments and no suspicious skin, eye or anal lesions were found; the diagnosis of primary esophageal melanoma was made. During his hospital stay, the patient developed a hospital-acquired respiratory infection. The patient died after 35 d, before tumor-directed treatment could begin.

Figure 1.

Coronal reformat of a contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography demonstrates a solid enhancing mass with soft tissue attenuation in the middle third of the esophagus (arrow) causing obstruction and proximal dilatation. The distal third of the esophagus (arrowheads) is unremarkable.

Figure 2.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy of the patient. A: Soft polypoid tumor protruding to the esophageal lumen, located 25cm to 35cm from the incisors; B: A closer view of the lesion shows that tumor surface is darker than esophageal mucosa due to its melanin content.

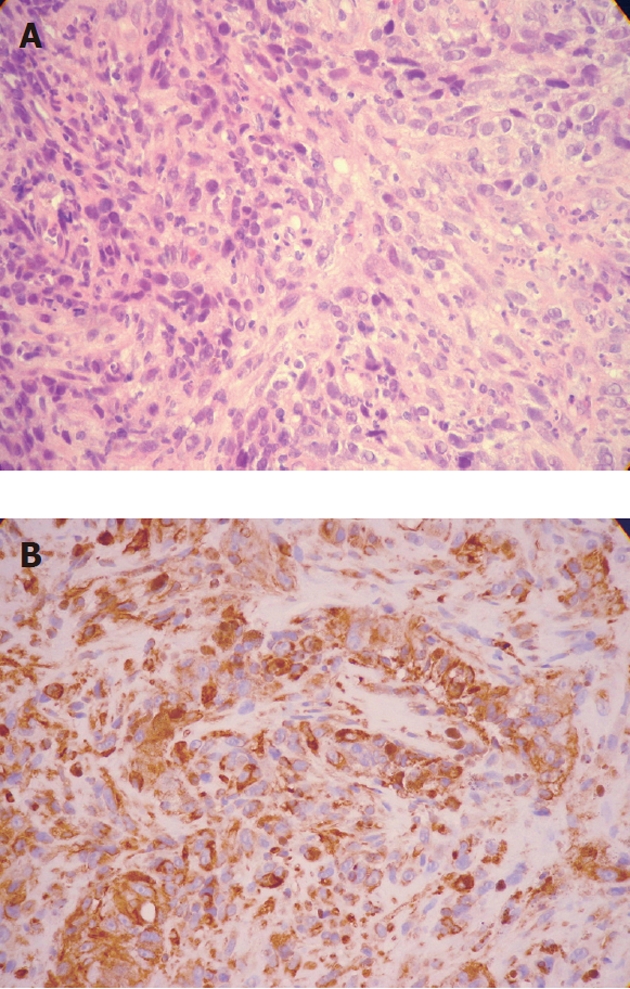

Figure 3.

Histopathological findings. A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining discloses crowded rounded or elongated cells within distinct cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (magnification, x 100); B: Immunohistochemical study for HMB45 (anti-melanoma protein mAb). The positive reaction (brown cytoplasmic reaction) supports the diagnosis of malignant melanoma (magnification, x 100).

DISCUSSION

Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus is a rare neoplasm and represents 0.1% to 0.2% of all esophageal malignant tumors and 0.5% of all noncutaneous melanomas[1].

The first to report a case of PMME was Bauer in 1906[2]. In 1952, Garfinkle and Cahan were the first to confirm the diagnosis with histological evidence[3]. The diagnosis remained controversial until 1963 when la Pava et al[4] demonstrated the presence of benign melanocytes within the esophageal mucosa in 4 of 100 autopsy specimens. Later, Tateishi et al[5] (1974) and Ohashi et al[6] (1990) confirmed this observation and demonstrated that 2.5 % to 8% of the general population has typical melanocytes within the esophageal mucosa[4-6].

The origin of melanocytes of the esophagus remains unclear. Two hypotheses are proposed: (1) migration of melanoblasts from the neural crest; and (2) pluripotent immature cells migrate to the esophagus and then differentiate into melanocytes[1,5].

Risk factors are not yet defined. No association between tobacco or alcohol consumption appears to exist. Melanosis, a benign condition defined as an increased number of melanocytes within the basal layer and an increased quantity of melanin in these melanocytes, has been indicated as a predisposing factor and it has been described in association with or preceding PMME[6,7]. In 2007, Oshiro et al[8] described a case of an esophageal melanotic lesion found incidentally during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy that after 19 mo of follow-up underwent malignant transformation.

PMME occurs predominantly in males between the ages of 50-70 years old[1,9,10]. One pediatric case has been reported[11] as well as another in a young adult[12]. A higher incidence of PMME has been described in Japan[1,9] and a greater number of esophageal melanocytes have been observed in this population[6].

Dysphagia, predominantly for solids, is the most frequent symptom at presentation (79.8% of all cases[1]). Retrosternal or epigastric discomfort or pain appears in 33.1% of the cases[1]. Occasionally, melena or hematemesis are reported, as occurred in our case. Symptoms are typically present for less than 3 mo[1]. The reported size of the tumors at diagnosis and the short duration of symptoms demonstrate that this is a rapidly growing neoplasm.

The characteristic endoscopic finding of PMME is as a polypoid lesion, with variable size, usually pigmented. The neoplasm occurs in the lower two-thirds of the esophagus in 86% of cases[10]. They are non-pigmented in 10%-25% of cases but melanin can be identified at histological examination in some of them[1,9,13]. The true incidence of amelanotic melanoma is less than 2%[14]. PMME should be included in the differential diagnosis list of all polypoid tumors found during endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus. Other possible diagnoses are leiomyoma, lipoma, fibroma, neurofibroma, some epidermoid carcinomas, sarcoma, small cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma and metastatic melanoma.

Thoracic and abdominal CT allows lesion visualization and staging. Barium swallow examination can show a bulky, polypoid intraluminal filling defect[15]. Endoscopic ultrasonography as a staging method has been used in a few cases but the results were coincident with those obtained in histological examination of the resected specimens[16-18].

Diagnostic criteria have been developed by Allen and Spitz[19] and include a typical histologic pattern of melanoma and the presence of melanin granules within the tumor cells; origin from squamous epithelium with junctional activity; junctional activity with melanotic cells in the adjacent epithelium. Histological examination of specimens obtained by endoscopic biopsies are often misdiagnosed and described as poorly differentiated carcinoma, especially when the melanoma cells contain few or no melanin granules (in the series of Sabanathan[1] only 54% of cases were diagnosed preoperatively as malignant melanoma). More recently, immunohistochemical staining with S-100 or anti-melanoma protein mAb (HBM-45) allows accurate identification of this kind of tumor.

PMME metastasizes via hematogenic and lymphatic pathways. At diagnosis, about 50% of patients present distant metastases to the liver (31%), the mediastinum (29%), the lungs (18%) and the brain (13%)[10].

Treatment should be individualized for each patient. The choice should be based on tumor size and location, presence or absence of metastases, age and comorbidities of the patient.

When possible, surgery (curative or palliative), is the preferential method of treatment. Radical resection with great margins is recommended as this tumor has a widespread intramucosal component. Survival after radical resection is 14.18 mo and after limited local excision is only 9 mo[1].

Adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemohormonotherapy are not globally beneficial. However, some authors have described sporadic successful cases using these therapies. A frequently utilized course, similarly to that used in cutaneous melanoma, includes dacarbazine, nimustin and vincristine. Two cases with at least 7 years survival have been described[20,21]. In 2004, Uetsuka et al[20] described a case using dacarbazine, nimustine, cisplatin and tamoxifen before and after surgery and interferon-β monthly only after surgery. In 2007, Kawada et al[21] described a case using chemotherapy (dacarbazine, nimustine and vincristine) and local endoscopic injection of interferon-β before and after surgery.

Radiotherapy can be effective but should be reserved for PMME with metastatic illness, patients with high surgical risk or for those who refuse a surgical approach[9]. When used as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy of radical surgery, a 16.72 mo survival was achieved[1].

Khoury-Helou et al[22] described a 9-year survival in the case of a patient who underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy (5-fluorouracile and cisplatin) and radiotherapy (40Gy) after identification of a ganglionar metastasis.

Immunotherapy using autologous monocyte-derived dendritic cells pulsed with the epitope peptides of melanoma-associated antigens (MAGE-1, MAGE-3), in association with passive immunotherapy with lymphokine-activated killer cells, is an alternative proposed for adjuvant treatment[23].

Intraluminal brachytherapy in association with photoablation with Nd: YAG laser has also been used as an alternative treatment for a patient with surgical contraindications[24]. Another option for palliative treatment is esophageal stent implantation[25].

The prognosis is poor; the mean survival after surgery is less than 15 mo[9,10]. At least 7 patients have survived 5 or more years; they were all submitted to total esophagectomy but only three of them were submitted to some kind of adjuvant treatment[20,22,26-30].

Eighty-five percent of PMME patients die of disseminated disease[1].

Our patient died of a fatal hospital-acquired infection and therefore was not submitted to any tumor-directed therapy. PMME represents a rare condition, especially in western countries. Clinicians should be aware of PMME when considering the differential diagnosis of an esophageal polypoid lesion. The prognosis is poor and treatment should be promptly initiated, yet there is no formal recommendation on this subject.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: John K Marshall, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology (4W8), McMaster University Medical Centre, 1200 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8N 3Z5, Canada

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Sabanathan S, Eng J, Pradhan GN. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1475–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baur EH. Ein Fall von primarein melanom des esophagus. Arb Geb Pathol Anat Inst Tubingen. 1906;5:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garfinkle JM, Cahan WG. Primary melanocarcinoma of the esophagus; fist histologically proved case. Cancer. 1952;5:921–926. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195209)5:5<921::aid-cncr2820050508>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De la Pava S, Nigogosyan G, Pickner JW, Cabrera A. Melanosis of the esophagus. Cancer. 1963;16:48–50. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196301)16:1<48::aid-cncr2820160107>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tateishi R, Taniguchi H, Wada A, Horai T, Taniguchi K. Argyrophil cells and melanocytes in esophageal mucosa. Arch Pathol. 1974;98:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohashi K, Kato Y, Kanno J, Kasuga T. Melanocytes and melanosis of the oesophagus in Japanese subjects--analysis of factors effecting their increase. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;417:137–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02190531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamazaki K, Ohmori T, Kumagai Y, Makuuchi H, Eyden B. Ultrastructure of oesophageal melanocytosis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1991;418:515–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01606502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oshiro T, Shimoji H, Matsuura F, Uchima N, Kinjo F, Nakayama T, Nishimaki T. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus arising from a melanotic lesion: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:671–675. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joob AW, Haines GK, Kies MS, Shields TW. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalkiadakis G, Wihlm JM, Morand G, Weill-Bousson M, Witz JP. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;39:472–475. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)61963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basque GJ, Boline JE, Holyoke JB. Malignant melanoma of the esophagus: first reported case in a child. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;53:609–611. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/53.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulafendis D, Damiani M, Sie E, Bastounis E, Samaan HA. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus in a young adult. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taniyama K, Suzuki H, Sakuramachi S, Toyoda T, Matsuda M, Tahara E. Amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus: case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1990;20:286–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe H, Yoshikawa N, Suzuki R, Hirai Y, Yoshie M, Ohshima H, Takahashi M, Takai M, Hosoda S, Asanuma K. Malignant amelanotic melanoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1991;26:209–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02811082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gollub MJ, Prowda JC. Primary melanoma of the esophagus: radiologic and clinical findings in six patients. Radiology. 1999;213:97–100. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.1.r99oc3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo CC, Levine MS, McLarney JK, Lowry MA. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: radiographic findings in seven patients. Radiology. 1998;209:455–459. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.2.9807573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Namieno T, Koito K, Ambo T, Muraoka S, Uchino J. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasonography. Am Surg. 1996;62:716–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshikane H, Suzuki T, Yoshioka N, Ogawa Y, Hamajima E, Hasegawa N, Nakamura S, Kamiya Y. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus presenting with massive hematemesis. Endoscopy. 1995;27:397–399. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen AC, Spitz S. Malignant melanoma; a clinicopathological analysis of the criteria for diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer. 1953;6:1–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195301)6:1<1::aid-cncr2820060102>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uetsuka H, Naomoto Y, Fujiwara T, Shirakawa Y, Noguchi H, Yamatsuji T, Haisa M, Matsuoka J, Gunduz M, Takubo K, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: long-term survival following pre- and postoperative adjuvant hormone/chemotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1646–1651. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000043379.60295.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawada K, Kawano T, Nagai K, Nishikage T, Nakajima Y, Tokairin Y, Ogiya K, Tanaka K, Iwai T. Local injection of interferon beta in malignant melanoma of the esophagus as adjuvant of systemic pre- and postoperative DAV chemotherapy: case report with 7 years of long-term survival. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:408–410. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khoury-Helou A, Lozac’h C, Vandenbrouke F, Lozac’h P. [Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus] Ann Chir. 2001;126:557–560. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(01)00553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueda Y, Shimizu K, Itoh T, Fuji N, Naito K, Shiozaki A, Yamamoto Y, Shimizu T, Iwamoto A, Tamai H, et al. Induction of peptide-specific immune response in patients with primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus after immunotherapy using dendritic cells pulsed with MAGE peptides. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:140–145. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wayman J, Irving M, Russell N, Nicoll J, Raimes SA. Intraluminal radiotherapy and Nd: YAG laser photoablation for primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:927–929. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)00339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastl S, Wutke R, Czeczatka P, Hohenberger W, Horbach T. Palliation of a primary malignant melanoma of the distal esophagus by stent implantation. Report of a case. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1042–1043. doi: 10.1007/s004640042030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suehs OW. Malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1961;70:1140–1147. doi: 10.1177/000348946107000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki H, Nagayo T. Primary tumors of the esophagus other than squamous cell carcinoma--histologic classification and statistics in the surgical and autopsied materials in Japan. Int Adv Surg Oncol. 1980;3:73–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamdy FC, Smith JH, Kennedy A, Thorpe JA. Long survival after excision of a primary malignant melanoma of the oesophagus. Thorax. 1991;46:397–398. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.5.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Mik JI, Kooijman CD, Hoekstra JB, Tytgat GN. Primary malignant melanoma of the oesophagus. Histopathology. 1992;20:77–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1992.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Itami A, Makino T, Shimada Y, Imamura M. A case of primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus with long term survival. Esophagus. 2004;1:135–137. [Google Scholar]