Abstract

Acute stress responses of women are typically more reactive than that of men. Women, compared to men, may be more vulnerable to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Whether there are differences between women and men with PTSD in levels of the stress hormone, cortisol, was investigated in a pilot study.

Methods

women (n=6) and men (n=3) motor vehicle accident (MVA) survivors, with PTSD, had saliva collected at 1400 h, 1800 h, and 2200 h. Cortisol levels in saliva were measured by radioimmunoassay. An interaction between gender and time of sample collection was observed due to women’s cortisol levels being lower and decreasing over time, whereas men’s levels were higher and increased across time of day of collection. Results of this pilot study suggest a difference in the pattern of disruption of glucocorticoid secretion among women and men with PTSD. Women had greater suppression of their basal cortisol levels than did men; however, the diurnal pattern for cortisol levels to decline throughout the day was observed among the women but not the men.

Keywords: Cortisol, Glucocorticoid, PTSD, Motor vehicle accident, MVA, Gender

1. Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder involving both somatic and psychological symptoms that occur in response to severe trauma. Although many different events contribute to the etiology of PTSD, motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) are a leading cause of PTSD in the general population [1]. The prevalence of PTSD resulting from a serious MVA is between 6 and 12%. However, smaller studies examining MVA survivors who have sought medical attention have prevalence rates of PTSD up to 100% [2] making PTSD a mental health problem of considerable magnitude, which needs to be better understood.

Acute stress is an adaptive physiological process. Normally, the autonomic nervous system is aroused, characterized by release of corticotrophin-releasing factor, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and glucocorticoids, such as cortisol, which can support emergent, adaptive responses and promote the termination of Hypothalamus–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis (HPA) reactivity through a negative feedback loop, maintaining homeostasis [3,4]. Although acute stress responses are beneficial in the short term, chronic stress can lead to suppression of HPA feedback and can contribute to numerous health problems. PTSD is characterized by aberrant HPA responding. Many studies have shown that people who have suffered from PTSD for 20 or more years have lower basal cortisol than do people without PTSD [5–10], although other studies found no difference [11–14]. Even among people who have recently had an MVA, levels of urinary or serum cortisol are lower among those reporting greater emotional numbing and intrusive thoughts of the MVA [15–17]. Altered HPA axis activity associated with extreme stress may contribute to the development of PTSD [18,19].

Gender differences in normal HPA reactivity may underlie women’s increased vulnerability to PTSD. More women than men are diagnosed with PTSD [20–23]. Additionally, an examination of gender’s effects on development of PTSD and HPA activity following an MVA revealed that more women (7 of 9) were diagnosed with PTSD [16]. In a separate investigation of those who were PTSD symptomatic 1 month after an MVA, men but not women, had significant increases in urinary cortisol levels compared to controls [15]. A large study of all male combat veterans found no differences in 24 hour urinary cortisol levels in comparison to controls [11]. These findings suggest that women with PTSD among women may be characterized by greater suppression of HPA reactivity compared to men with PTSD.

To date, the majority of research that has focused on both PTSD symptomology and HPA reactivity has utilized samples of individuals having undergone extreme stress, such as combat veterans who were mostly men. Our preliminary study examined gender differences in cortisol levels of MVA survivors with PTSD. It was hypothesized that women with PTSD would have lower basal cortisol levels than men with PTSD.

2. Methods

These methods were pre-approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University at Albany-SUNY.

2.1. Subjects

Data for 9 MVA survivors who received medical attention within 48 h of their accident was analyzed. All participants met diagnostic criteria for full PTSD at an assessment that took place 6 to 24 months post-MVA. Of the 9 participants, there were 3 men and 6 women, all of whom were Caucasian-American. The mean age of the sample was 34.5 years (SD=6.4) ranging from 28 to 44 years. The mean age of the men was 35.0 years (SD=4.7), while the mean age of the women was 34.3 years (SD=3.6).

2.2. Measures

The Clinician Administered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS), which is a valid and reliable measure for assessing PTSD, was used to diagnose PTSD [24–26]. The average CAPS score for men was 60.6 (SD=7.8) while the average CAPS score for women was 60.3 (SD=12.0).

2.3. Sample collection

Participants were recruited through referrals made by medical professionals, local media coverage, and advertising. Participants were invited to The Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders at The University at Albany-SUNY for an assessment of PTSD. During the visit, the CAPS was administered. On a separate day within a week of the assessment, saliva samples were collected at 1400 h,1800 h, and 2200 h using Salivette collection devices. The average length of time between MVA and data collection was 11.1 months (women=10.6 months, men=12.0 months).

2.4. Cortisol measurement

Samples were transported to the laboratory of Dr. Bremner at Yale University and stored at −70 °C until radioimmunoassay. For measurement, saliva was extracted from salivette tubes by centrifugation at −4 °C. Saliva (200 μl) was assayed in duplicate for cortisol using a commercially available kit from Diagnostic Products Incorporated (Los Angeles, CA), which uses 125I as a tracer. Standards ranged in concentration from 67 pg/ml to 3 ng/ml. Coefficients of inter- and intra-assay variance were 0.10 and 0.08, respectively [27].

2.5. Statistical analysis

There were 2 participants (1 man, 1 woman) that had a single inadequate or missing data point. These 2 data points were imputed to enable more complete analysis with a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). To examine the effects on basal salivary cortisol levels, the time of saliva collection was utilized as the within-factor and gender was the between-factor.

3. Results

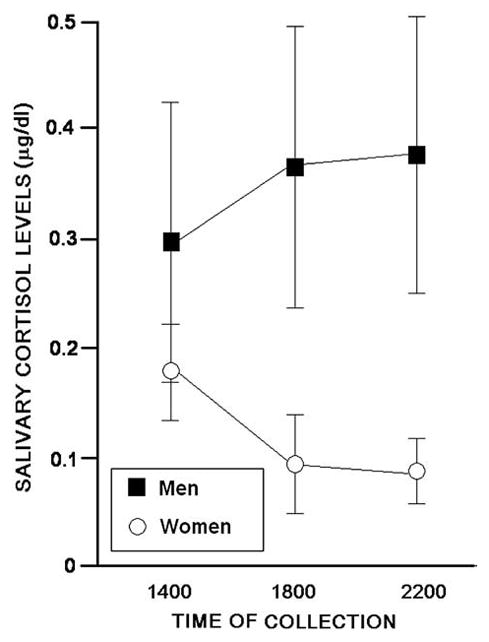

There was a tendency for a main effect of gender on basal salivary cortisol levels, F (1,7)=4.847, p<0.06), with men having higher basal salivary cortisol levels than women. There was a significant interaction between gender and time of sample collection, F (2,14)=4.782, p<0.02). As Fig. 1 illustrates, the interaction was due to cortisol levels for women being lower and decreasing over time, whereas, the cortisol levels of men were higher and did not decrease over time.

Fig. 1.

The mean (±S.E.M.) basal cortisol levels collected at 1400 h,1800 h and 2200 h of men (filled squares) and women (open circles) with posttraumatic stress disorder.

4. Discussion

The results supported the hypothesis that women with PTSD would have lower basal cortisol levels than men with PTSD. Although women had lower basal cortisol levels than did men, suggesting suppression of their glucocorticoid secretion, the normal diurnal pattern for cortisol was preserved among women but not men. Because cortisol levels follow a circadian pattern where they are higher in the morning and decline throughout the day, we collected samples at different times of the day. It is notable that for each of the 6 women in our study, but none of the men, cortisol levels were lower at later time points compared to that of the earlier, initial sampling. These data support the notion that there may be differences in the manner in which glucocorticoid secretion is disrupted among men and women with PTSD. Women with PTSD had lower basal cortisol levels than did their male counterparts, whereas, men with PTSD had greater cortisol concentrations than are typical and demonstrated an aberrant circadian pattern of secretion.

Although these findings are intriguing, they are limited. First, the small sample limited the power of the statistical analyses. As well, menstrual cycle variations were not controlled for and so, endogenous sex hormone variations could not be taken into account. Despite these limitations, statistically-significant differences by gender were observed. This may be attributed to the consistently very low, basal cortisol levels among the women in our study. However, future investigations will aim to recruit a larger sample so that influences of menstrual cyclicity, which have been demonstrated to influence HPA function [28], can be assessed. Second, there was no non-PTSD control group, which made it difficult to ascertain the extent to which the findings were unique to PTSD. However, we have been able to consider these findings with respect to unpublished data from our laboratory wherein college-aged men (n=13) and women (n=11) had salivary cortisol levels determined between the hours of 1200 and 1500 and. These men and women had salivary cortisol (mean±SEM) concentrations that were 0.41±0.12 (SD=0.30, range 0.09–0.87) and 0.37±0.08 (SD=0.42, range 0.01–0.49), respectively. In lieu of these data, men with MVA-PTSD appear to be closer to what may be a more normative range for cortisol concentration at this period in the day, albeit the loss of circadian rhythm remains aberrant. Women with MVA-PTSD appear to be well below what may be typical for salivary cortisol at this period of the day. Irrespective of these comparisons, our unpublished data highlight the fact that the gender differences between men and women with MVA-PTSD are greater than that which is expected and has been demonstrated in the past by this group and others [29–31]. Third, it is also noted that a larger sample size would allow these investigations to take into account the extent to which individual differences in circadian rhythm account for observed effects among MVA-PTSD victims.

Despite the limitations of this study, the present results confirm past findings in several ways. First, as in previous experiments [6,7,10], basal cortisol levels among people with chronic PTSD were very low. Second, men with PTSD had higher levels of cortisol than did their female counterparts, which is congruous with previous findings that 1 month after an MVA, men with PTSD had higher urinary cortisol levels than did women with PTSD [15]. In Hawk’s study, men, but not women with PTSD, had significantly elevated urinary cortisol levels compared to non-PTSD controls. These findings, while preliminary, are consistent with men with PTSD having less suppression of their basal glucocorticoid secretion than do women.

It is particularly important to understand gender differences in glucocorticoid secretion in neuropsychiatric disorders. Women are more prone to neuropsychiatric disorders that are influenced by stress and dysregulation of the HPA axis, such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD [21,22–35]. Given that HPA hyperactivity has been proposed to precede HPA hypo-responsiveness [36], the present study may suggest that there is a gender difference in the time-course of HPA attenuation. Among non-afflicted women, endogenous hormone concentrations can alter HPA activity [28] which may underlie some of the observed gender differences in HPA responsiveness. Yet, it is not known whether this is associated with differences in severity of PTSD symptoms. It has been proposed that irregularities in glucocorticoid secretion among people with PTSD may be related to hyperadrenergic states and/or catecholaminergic dysfunction [6,37]. It is well known in non-PTSD populations, that women are more stress responsive than men [38–40] and that circulating gonadal hormones influence stress responsiveness [41–43]. Further investigation of gender and/or hormonal factors may reveal the basis for the increased incidence of PTSD among women. Future investigations will aim to assess these differences in larger samples throughout the day in a controlled manner.

Acknowledgments

Research described was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH48476, MH6769801, and MH056120).

References

- 1.Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:409–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ. After the crash: Psychological assessment and treatment of survivors of motor vehicle accidents. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munck A, Guyre PM, Holbrook NJ. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocr Rev. 1984;5:25–44. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yehuda R. Sensitization of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Yehuda R, McFarlane AC, editors. Psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. New York: Academy of Sciences; 1997. pp. 57–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mason JW, Giller EL, Kosten TR, Ostroff RB, Podd L. Urinary free-cortisol levels in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174:145–9. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yehuda R, Southwick SM, Nussbaum G, Wahby V, Giller EL, Mason JW. Low urinary cortisol excretion in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178:366–9. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yehuda R, Lowy MT, Southwick SM, Shaffer D, Giller EL. Lymphocyte glucocorticoid receptor number inposttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:499–504. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yehuda R, Boisoneau D, Mason JW, Giller EL. Glucocorticoid receptor number and cortisol secretion in mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34:18–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yehuda R, Boisoneau D, Lowy MT. Dose–response changes in plasma cortisol and lymphocyte glucocorticoid receptors following dexamethasone administration in combat veterans with and without PTSD. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:583–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950190065010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yehuda R, Kahana B, Binder-Byrnes K, Southwick SM, Mason JW, Giller EL. Low urinary cortisol excretion in Holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:982–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason J, Wang S, Yehuda R, Lubin H, Johnson D, Bremner JD, et al. Marked lability of urinary free cortisol levels in sub-groups of combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:238–46. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young EA, Breslau N. Cortisol and catecholamines in posttraumatic stress disorder: an epidemiological community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:394–401. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young EA, Toman T, Witkowski K, Kaplan G. Salivary cortisol and posttraumatic stress disorder in a low-income community sample of women. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;55:621–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitman RK, Orr SP. Twenty-four hour urinary cortisol and catecholamine excretion in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;27:245–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90654-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawk LW, Dougall AL, Ursano RJ, Baum A. Urinary catecholamines and cortisol in recent onset posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. Psychosom Med. 2000;42:423–34. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delahanty DL, Raimonde AJ, Spoonster E. Initial posttraumatic urinary cortisol levels predict subsequent PTSD symptoms in motor vehicle accident victims. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:940–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00896-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFarlane AC, Atchison M, Yehuda R. The acute stress response following motor vehicle accidents and its relation to PTSD. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;821:437–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitman RK. Editorial, posttraumatic stress disorder, hormones, and memory. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;26:221–3. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitman RK, Orr SP, Lowenhagen ML, Macklin ML, Altman B. Pre-Vietnam contents of posttraumatic stress disorder veterans’ service medical and personal records. Compr Psychiatry. 1991;32:416–22. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(91)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. Sex differences in post-traumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1044–88. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230082012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aardal-Eriksson E, Eriksson TE, Thorel LH. Salivary cortisol, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and general health in the acute phase and during 9-month follow-up. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:986–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanitallie TB. Stress: a risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism. 2002;51:40–5. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blake D, Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Klauminzer G, Charney D, et al. National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Boston: Behavioral Science Division; 1998. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:132–56. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weathers FW, Litz BT. Psychometric properties of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, CAPS-I. PTSD Res Q. 1994;5:2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Vermetten E, Adil J, Khan S, Nazeer A, et al. Cortisol response to a cognitive stress challenge in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to childhood abuse. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:733–50. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCormick CM, Teillon SM. Menstrual cycle variation in spatial ability: relation to salivary cortisol levels. Horm Behav. 2001;39:29–38. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paris JJ, Franco C, Sodano R, Frye CA, Wulfert E. Gambling pathology is associated with dampened cortisol response among men and women. Physiol Behav. 2010;99:230–3. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paris JJ, Franco C, Sodano R, Freidenberg B, Gordis E, Anderson DA, et al. Sex differences in salivary cortisol to acute stressors among healthy participants, recreational or pathological gamblers, and those with posttraumatic stress disorder. Horm Behav. 2009;98:281–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Stegeren AH, Wolf OT, Kindt M. Salivary alpha amylase and cortisol responses to different stress tasks: impact of sex. Int J Psychophysiol. 2008;69:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desai HD, Jann MW. Major depression in women: a review of the literature. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40:525–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenkins R. Sex differences in depression. Br J Hosp Med. 1987;38:485–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mischler SA, Hough LB, Battles AH. Characteristics of carbon dioxide induced antinociception. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;53:205–12. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young EA. Sex differences in the HPA axis: implications for psychiatric disease. J Gend Specif Med. 1998;1:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McEwen BS. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deconess Medical Center: protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yehuda R, McFarlane AC, Shalev AY. Predicting the development of posttraumatic stress disorder from the acute response to a traumatic event. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1305–13. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallucci WT, Baum A, Laue L, Rabin DS, Chrousos GP, Gold PW, et al. Sex differences in sensitivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Health Psychol. 1993;12:420–5. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heuser IJ, Gotthardt U, Schweiger U, Schmider J, Lammers CH, Dettling M, et al. Age associated changes of pituitary-adrenocortical hormone regulation in humans: importance of gender. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15:227–31. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jezova D, Jurankova E, Mosnarova A, Kriska M, Skultetyova I. Neuroendocrine response to stress with relation to gender differences. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 1996;56:779–85. doi: 10.55782/ane-1996-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altemus M, Roca C, Galliven E, Romanos C, Deuster P. Increased vasopressin and adrenocorticotropin responses to stress in the mid luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2525–30. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duka T, Tasker R, McGowen JF. The effects of a three-week estrogen hormone replacement on cognition in elderly healthy females. Psychopharmacology. 2000;149:129–39. doi: 10.1007/s002139900324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Leo V, La Marca A, Talluri B, D’Antona D, Morgante G. Hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis and adrenal function before and after ovariectomy in premenopausal women. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:430–5. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1380430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]