Abstract

Increased cholangiocyte growth is critical for the maintenance of biliary mass during liver injury by bile duct ligation (BDL). Circulating levels of testosterone decline following castration and during cholestasis. Cholangiocytes secrete sex hormones sustaining cholangiocyte growth by autocrine mechanisms. We tested the hypothesis that testosterone is an autocrine trophic factor stimulating biliary growth. The expression of androgen receptor (AR) was determined in liver sections, male cholangiocytes, and cholangiocyte cultures [normal rat intrahepatic cholangiocyte cultures (NRICC)]. Normal or BDL (immediately after surgery) rats were treated with testosterone or antitestosterone antibody or underwent surgical castration (followed by administration of testosterone) for 1 wk. We evaluated testosterone serum levels; intrahepatic bile duct mass (IBDM) in liver sections of female and male rats following the administration of testosterone; and secretin-stimulated cAMP levels and bile secretion. We evaluated the expression of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 (17β-HSD3, the enzyme regulating testosterone synthesis) in cholangiocytes. We evaluated the effect of testosterone on the proliferation of NRICC in the absence/presence of flutamide (AR antagonist) and antitestosterone antibody and the expression of 17β-HSD3. Proliferation of NRICC was evaluated following stable knock down of 17β-HSD3. We found that cholangiocytes and NRICC expressed AR. Testosterone serum levels decreased in castrated rats (prevented by the administration of testosterone) and rats receiving antitestosterone antibody. Castration decreased IBDM and secretin-stimulated cAMP levels and ductal secretion of BDL rats. Testosterone increased 17β-HSD3 expression and proliferation in NRICC that was blocked by flutamide and antitestosterone antibody. Knock down of 17β-HSD3 blocks the proliferation of NRICC. Drug targeting of 17β-HSD3 may be important for managing cholangiopathies.

Keywords: biliary epithelium, biliary secretion, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3, secretin, sex hormones

in addition to playing a key role in the ductal secretion of water and bicarbonate (mainly regulated by secretin) (3, 30), cholangiocytes are the target cells in a number of chronic cholestatic liver diseases (termed cholangiopathies), including primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) (5, 8). During the progression of cholangiopathies, the balance between the proliferation/loss of cholangiocytes is critical for the maintenance of biliary secretory function and intrahepatic bile ductal mass (5, 8, 34, 36). Cholangiocytes respond to cholestasis and liver injury with changes in proliferation and ductal bile secretion (2, 3, 18, 22). In response to bile duct ligation (BDL), there is enhanced biliary hyperplasia and secretin-stimulated choleresis (a functional marker of cholangiocyte growth) (2, 3, 18, 22), whereas, following the administration of hepatotoxins (e.g., carbon tetrachloride), there is loss of cholangiocyte mass and secretory function (36). Indeed, proliferating cholangiocytes serve as neuroendocrine cells secreting and responding to a number of hormones and neuropeptides contributing to the autocrine and paracrine pathways that modulate the homeostasis of the biliary epithelium (8, 16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 39).

Cholangiocyte growth/apoptosis is regulated by a number of factors, including gastrointestinal hormones, the second messenger system, cAMP, and sex hormones, including estrogens, prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone, and progesterone (7, 8, 17, 23, 39, 49). Regarding sex hormones, estrogens have been shown to sustain cholangiocyte proliferation and reduce cholangiocyte apoptosis (6, 7). Prolactin is expressed and secreted by cholangiocytes and stimulates the growth of cholangiocytes by an autocrine mechanism (49). Progesterone enhances the proliferative activity of female and male cholangiocytes via autocrine mechanisms, since cholangiocytes possess the enzymatic pathway for steroidogenesis (23). Follicle-stimulating hormone increases cholangiocyte proliferation by an autocrine mechanism via cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Elk-1 (39).

Testosterone is an anabolic steroid that is primarily secreted in the testes of males and the ovaries of females, although small amounts are also secreted by the adrenal glands. Testosterone is thought to predominantly mediate its biological effects through binding to the androgen receptor (AR) (43). Similar to other members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, ARs function as a ligand-inducible transcription factor. ARs are expressed in the liver by hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatocytes in areas of ductular metaplasia, and in a number of metastatic adenocarcinomas, including bile duct cholangiocarcinoma (26, 44, 47). However, no information exists regarding the expression and role of testosterone and its receptors in the regulation of cholangiocyte growth and ductal secretory activity in cholestasis. The rate-limiting step in the synthesis of testosterone from androstenedione (a product of dehydroepiandrosterone and progesterone, both of which are products of pregnenolone and cholesterol) depends on the enzyme 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 (17β-HSD3) (20). On the basis of these findings, we performed experiments aimed to demonstrate that: 1) reduction of testosterone serum levels decreases cholangiocyte proliferation; 2) testosterone administration stimulates biliary growth and prevents the decrease in biliary hyperplasia induced by castration; 3) cholangiocytes express 17β-HSD3 and secrete testosterone regulating biliary by an autocrine mechanism; and 4) silencing of 17β-HSD3 (the enzyme regulating testosterone synthesis) (20) decreases biliary proliferation in vitro. The data suggest an autocrine compensatory role of testosterone in sustaining cholangiocyte proliferation in cholestasis, a pathological condition characterized by testicular atrophy and lowered serum testosterone levels (14, 33, 54, 57).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. The monoclonal mouse antibody (clone PC-10) reacting with proliferating cellular nuclear antigen (PCNA) and the goat polyclonal antibody (antibody raised against a peptide mapping within an internal region of AR of human origin) reacting with both subtypes of AR were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The AR antibody (G-13) is recommended for the detection of AR of mouse, rat, and human origin. The substrate for γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (γ-GT), N-(γ-l-glutamyl)-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide, was purchased from Polysciences (Warrington, PA). The enzyme-linked immunosorbebt assay (ELISA) kit used for measuring testosterone levels in serum and supernatant of primary cultures (after 6 h of incubation at 37°C) of isolated cholangiocytes from the selected groups of rats and primary cultures of rat intrahepatic cholangiocyte cultures [normal rat intrahepatic cholangiocyte cultures (NRICC)] from normal male rats (4) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). The RIA kit (125I-cAMP Biotrak Assay System, RPA509) for the determination of intracellular cAMP levels in purified cholangiocytes was purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ).

Animals.

Female and male 344 Fischer rats (150–175 g) were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and maintained in a temperature-controlled environment (20–22°C) with 12:12-h light-dark cycles. Animals were fed ad libitum standard chow and had free access to drinking water. The studies were performed in: 1) normal and BDL female and male rats treated with sesame oil (vehicle) or testosterone in sesame oil (2.0 mg/100 g body wt) (10); 2) normal male rats with castration (bilateral orchiectomy) (40) or sham; and 3) BDL (for collection of liver blocks and cell isolation) (3) male rats (immediately after surgery) (3) that underwent sham or castration (40) followed by daily intraperitoneal injections of sesame oil or testosterone in sesame oil (2.0 mg/100 g body wt) (10) for 7 days. In other experiments, we treated BDL (immediately after surgery) male rats with nonimmune serum or a polyclonal immune-neutralizing testosterone antibody (6.5 nmol/dose ip every day, a dose similar to that used by us for immunoneutralizing other sex hormones such as progesterone) (23) for 7 days before collecting serum and liver blocks for the determination of biliary growth and apoptosis. Immediately after bile duct incannulation (for bile collection) (3), male rats underwent sham for castration or castration (followed by the administration of sesame oil or testosterone in sesame oil, 2.0 mg/100 g body wt for 1 wk) (10) before evaluating the effect of intravenous infusion of secretin on bile and bicarbonate secretion (3). Because there was no difference in biliary growth (data not shown) between normal rats treated with sesame oil and sham rats for castration or BDL rats treated with sesame oil or nonimmune serum and BDL sham rats for castration, we used only normal and BDL rats as controls in our study. Seven days later, the animals were killed for the collection of serum, liver block, bile, and cholangiocytes. Before each procedure, animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body wt ip) according to the regulations of the panel on euthanasia of the American Veterinarian Medical Association and local authorities. All experiments were reviewed and approved by the Scott & White Hospital/Texas A&M Health Science Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Purification of cholangiocytes and hepatocytes.

Virtually pure cholangiocytes (∼98% by γ-GT histochemistry) (46) were isolated by immunoaffinity separation (27) using a mouse monoclonal antibody (IgM, kindly provided by Dr. R. Faris, Brown University, Providence, RI) that recognizes an unidentified antigen expressed by all intrahepatic rat cholangiocytes (27). Cell viability (by trypan blue exclusion) was ∼98%. Hepatocytes were isolated from normal and BDL male rats as described (27). Male NRICC, which display morphological, phenotypic, and functional phenotypes similar to that of freshly isolated cholangiocytes, were developed, characterized, and maintained in culture as described by us (4).

Expression of AR and 17β-HSD3.

The presence of AR was evaluated by: 1) immunofluorescence (16) in frozen liver sections (4–5 μm thick) and immunohistochemistry (39) in paraffin-embedded liver sections (4–5 μm thick) from normal and BDL male rats; and 2) RT-PCR (1) and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (45) in cholangiocytes and hepatocytes from normal and BDL male rats. In NRICC, the expression of AR was also evaluated by RT-PCR and immunofluorescence (39). For all immunoreactions, negative controls (with normal serum from the same species substituted for the primary antibody) were included.

With regard to RT-PCR (performed using the GeneAmp RNA PCR kit from Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, NJ), specific oligonucleotide primers were based on the sequence of the rat AR (11) (sense, 5′-CCCTGTGTGTGCAGCTAGAA-3′ and antisense, 5′-TAGACAGGATCTGCCCTGCT-3′), with an expected fragment length of 247 bp; we used RNA (1 μg) from rat testicles and yeast-transfer RNA as positive and negative controls, respectively. The comparability of the RNA used was assessed by RT-PCR for the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (sense 5′-GTGACTTCAACAGCAACTCCCATTC-3′ and antisense 5′-GTTATGGGGTCTGGGATGGAATTGTG-3′), with an expected fragment length of 294 bp; primers were based on the rat GAPDH sequence (15); rat kidney and yeast transfer RNA were the positive and negative controls for the GAPDH gene, respectively. Standard RT-PCR conditions were used, consisting of 35 step cycles: 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C for AR and 52°C for GAPDH for 45 s at 72°C. FACS analysis for AR was performed in isolated cholangiocytes and hepatocytes from normal and BDL rats using a C6 flow cytometer and analyzed by CFlow Software (Accuri Cytometers, Ann Arbor, MI). At least 20,000 events in the light scatter (side scatter/forward scatter) were acquired. The expression of AR was identified and gated on fluorescence channel 1-A (FL1-A)/count plots. The relative quantity of AR (mean selected protein fluorescence) was expressed as mean FL1-A (samples) per mean FL-1A (secondary antibodies only). The standard errors were calculated as (CV FL1-A) × (mean FL1-A)/SQR(count 1), where CV is coefficient of variation and SQR is square root.

We evaluated the expression of 17β-HSD3 (37) by: 1) immunofluorescence (16) in frozen liver sections (4–5 μm thick) and immunohistochemistry (39) in paraffin-embedded liver sections (4–5 μm thick) from normal and BDL male rats; 2) real-time PCR (16) and FACS analysis (45) (see above) in freshly isolated male cholangiocytes; and 3) real-time PCR and immunofluorescence (16) in male NRICC. For all immunoreactions, negative controls (with normal serum from the same species substituted for the primary antibody) were included. Following immunofluorescence for AR and 17β-HSD3, images were visualized using an Olympus IX-71 confocal microscope. Light microscopy photographs of liver sections stained for AR and 17β-HSD3 were taken by Leica Microsystems DM 4500 B Light Microscopy (Weltzlar, Germany) with a Jenoptik Prog Res C10 Plus Videocam (Jena, Germany). The positivity of bile ducts for AR and 17β-HSD3 was evaluated as described by us (25). When 0–5% of bile ducts were positive for AR and 17β-HSD3, we assigned a negative score; a ± score was assigned when 6–10% of bile ducts were positive; a + score was assigned when 11–30% of bile ducts were positive; a ++ score was assigned with 31–60% of bile ducts positive; and a +++ score was assigned when >61% of bile ducts were positive. Two pathologists performed the evaluations in a blinded manner.

For real-time PCR, total RNA was extracted from cholangiocytes by the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse transcribed using the Reaction Ready First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (SuperArray, Frederick, MD). These reactions were used as templates for the PCR assays using a SYBR Green PCR master mix and specific primers designed against the rat 17β-HSD3 NM_054007 (51) and GAPDH, the housekeeping gene (SuperArray), in the real-time thermal cycler (ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system). A ΔΔCT (delta delta of the threshold cycle) analysis was performed using normal cholangiocytes as the control sample. Data are expressed as fold change of relative mRNA levels ± SE (n = 6).

Evaluation of testosterone serum levels, cholangiocyte apoptosis, and intrahepatic bile duct mass in liver sections.

Testosterone serum levels in female and male rats were measured by commercially available ELISA kits (Cayman Chemical). Cholangiocyte apoptosis was evaluated in paraffin-embedded liver sections (4–5 μm thick) by a quantitative terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) kit (Apoptag; Chemicon International) (39). The percentage of TUNEL-positive cholangiocytes was counted in six nonoverlapping fields (magnification ×40) for each slide; the data are expressed as the percentage of TUNEL-positive cholangiocytes. The number of intrahepatic bile ducts in frozen liver sections (4–5 μm thick) was determined by the evaluation of intrahepatic bile duct mass (IBDM) by point-counting analysis (35, 56). IBDM was measured as the percentage area occupied by γ-GT-bile duct/total area × 100 (35, 56). Morphometric data were obtained in six different slides for each group; for each slide, we performed the counts in six nonoverlapping fields (n = 36). Following the selected staining, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin and analyzed for each group using a BX-51 light microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of basal and secretin-stimulated cAMP levels and bile secretion.

At the functional level, cholangiocyte proliferation was evaluated by measurement of basal and secretin-stimulated cAMP levels in purified cholangiocytes by RIA (17, 22, 32) and bile and bicarbonate secretion in bile fistula rats (3), two functional indexes of cholangiocyte proliferation (3, 17, 22). For the measurement of cAMP levels (17, 22), purified cholangiocytes (1 × 105) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and incubated for 5 min at room temperature with 0.2% BSA (basal) or 100 nM secretin with 0.2% BSA (17, 22, 32). Following anesthesia with pentobarbital sodium, rats were surgically prepared for bile collection (3). When steady-state bile flow was reached [60–70 min from the infusion of Krebs-Ringer-Henseleit (KRH) solution], the animals were infused by a jugular vein with secretin (100 nM) for 30 min followed by a final infusion of KRH for 30 min. Bile was collected every 10 min in preweighed tubes that were used for determining bicarbonate concentration. Bicarbonate concentration (measured as total CO2) in the selected bile sample was determined by an ABL 520 Blood Gas System (Radiometer Medical, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Effect of testosterone on the expression of 17β-HSD3 and proliferation of NRICC: Effect of pharmacological inhibition and molecular silencing of 17β-HSD3 on NRICC proliferation.

To obtain a dose-response curve, NRICC were treated with vehicle (1% methanol, where testosterone is dissolved, basal value) or testosterone (10−5 to 10−11 M for 7 days in 1% methanol) before evaluating cell proliferation by MTS assays (16). We also evaluated the effects of testosterone on the expression of message for 17β-HSD3 in NRICC. NRICC were stimulated with vehicle (1% methanol, where testosterone is dissolved, basal value) or testosterone (100 nM for 6, 24, 48, and 72 h in 1% methanol) before measuring 17β-HSD3 mRNA expression by real-time PCR (see above) (16).

In separate experiments, NRICC (after trypsinization) were seeded into 96-well plates (10,000/well) in a final volume of 200 μl of medium and allowed to adhere to the plate overnight. NRICC were incubated at 37°C with 0.2% BSA (basal), flutamide (a specific antagonist of AR, 10 μM) (28), or antitestosterone antibody (100 ng/ml with 0.2% BSA) for 48 h before evaluation of proliferation by MTS assays (16).

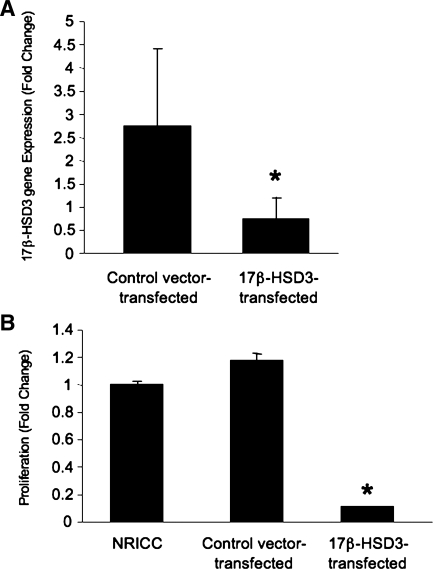

Furthermore, following stable transfection of 17β-HSD3 in NRICC (24), we measured the basal proliferative rates of the cells (after incubation for 24, 48, and 72 h at 37°C) by PCNA immunoblots and MTS assays (16). NRICC lacking 17β-HSD3 was established using SureSilencing shRNA (SuperArray) plasmid for rat 17β-HSD3 containing a marker for neomycin resistance for the selection of stably transfected cells, according to the instructions provided by the vendor as described by us (13). A total of four clones were assessed for the relative knock down of the 17β-HSD3 gene using real-time PCR (∼80% knock down), and a single clone with the greatest degree of knock down was selected for subsequent experiments. In control vector- and 17β-HSD3-knocked cells, we also evaluated the amount of secreted testosterone (by ELISA kits) after incubation for 24 h at 37°C.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between groups were analyzed by the Student's unpaired t-test when two groups were analyzed and ANOVA when more than two groups were analyzed, followed by an appropriate post hoc test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Expression of AR.

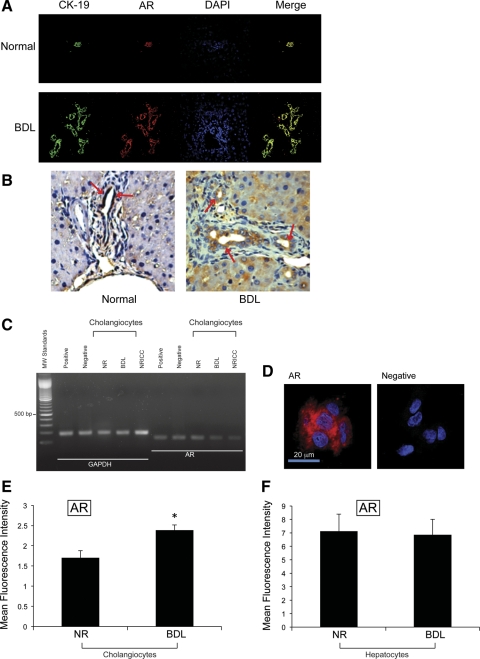

By both immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry in liver sections, we demonstrated that intrahepatic bile ducts from normal and BDL male rats express AR (Fig. 1, A and B). Colocalization of CK-19 (a cholangiocyte-specific marker) (18) with intrahepatic bile ducts expressing AR is visible in Fig. 1A. By immunohistochemistry, normal cholangiocytes and hepatocytes express low levels of AR, expression that increased following BDL (Fig. 1, A and B, and Table 1). By RT-PCR, the message for AR (247 bp) was expressed by freshly isolated cholangiocytes and hepatocytes from normal and BDL male rats and NRICC (Fig. 1C); the housekeeping gene, GAPDH mRNA (294 bp), was similarly expressed by these cells (Fig. 1C). By immunofluorescence, NRICC also expressed the protein for AR (Fig. 1D). We also demonstrated by FACS analysis the presence of AR in freshly isolated cholangiocytes and hepatocytes from normal and BDL male rats (Fig. 1, E and F); the expression of AR was upregulated in BDL compared with normal cholangiocytes (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

A: image showing that intrahepatic bile ducts from normal and bile duct ligation (BDL) male rats express androgen receptor (AR) (red staining). Colocalization with CK-19 (green staining) of bile ducts expressing the AR (red staining) is also visible. Bar = 50 μm. B: by immunohistochemistry, normal cholangiocytes and hepatocytes express low levels of AR, expression that increased following BDL (A and B; see Table 1). Original magnification, ×40. C: by RT-PCR, the message for AR was expressed by freshly isolated cholangiocytes from normal (NR) and BDL rats and normal rat intrahepatic cholangiocyte cultures (NRICC); the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), was expressed similarly by these cells. MW, mol wt. D: by immunofluorescence, NRICC also expressed the protein for AR. Bar = 20 μm. E and F: fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis shows the presence of the protein for AR in freshly isolated cholangiocytes and hepatocytes from normal and BDL male rats; the expression of AR seemed upregulated (*P < 0.05) in BDL cholangiocytes compared with normal cholangiocytes. Data are means ± SE of 3 determinations.

Table 1.

Semiquantitative analysis of AR expression in liver sections from normal and BDL male rats

| Normal | BDL | |

|---|---|---|

| Cholangiocytes | + | ++ |

| Hepatocytes | ± | + |

AR, androgen receptor; BDL, bile duct ligation. Grading scale: - = 0–5%; ± = 6–10%; + = 11–30%; ++ = 31–60%; +++ = >61%.

Evaluation of testosterone serum levels, cholangiocyte apoptosis, and IBDM in liver sections.

Parallel to previous studies (53, 54), testosterone serum levels were lower in female and male BDL rats compared with their corresponding normal rats (Fig. 2A). The serum levels of testosterone were lower in female rats compared with the corresponding values of male rats (Fig. 2B). The administration of testosterone increased testosterone serum levels in normal and BDL male rats (Fig. 2, A and B). Castration significantly decreased testosterone serum levels in normal and BDL male rats (Fig. 2B) (31). Similarly, administration of neutralizing antitestosterone antibody decreased testosterone serum levels in both normal and BDL male rats compared with rats treated with nonimmune serum (Fig. 2B). The administration of testosterone to BDL castrated rats partly prevented castration-induced reduction of testosterone serum levels (Fig. 2B). In female and male BDL rats, there was increased IBDM compared with their corresponding normal rats (Table 2) (3). Also, testosterone increased IBDM in normal (data not shown) and BDL female and male rats (Table 2) compared with rats treated with vehicle. Consistent with the concept that testosterone is a trophic factor for cholangiocyte growth, castration (which reduces serum testosterone levels) (31) decreased IBDM in both normal (data not shown) and BDL rats compared with rats without castration (Table 2). We next demonstrated that administration of an antitestosterone antibody (which reduces the circulating levels of testosterone) decreased IBDM compared with control BDL rats (Table 2), and administration of testosterone partly prevented castration-induced loss of IBDM (Table 2). In BDL castrated rats and BDL rats treated with antitestosterone antibody, there was an increase in apoptosis compared with BDL rats (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Measurement of serum testosterone levels in the selected groups of animals. Testosterone serum levels were lower in female and male BDL rats compared with their corresponding normal rats. The administration of testosterone increased testosterone serum levels in normal and BDL female and male rats. Castration significantly decreased testosterone serum levels in normal and BDL rats. Administration of neutralizing antitestosterone antibody decreased testosterone serum levels in both normal and BDL rats compared with rats treated with nonimmune serum. The administration of testosterone to BDL castrated rats partly prevented castration-induced reduction of testosterone serum levels. Data are means ± SE of 12 cumulative determinations. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding values of normal rats. #P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding values of normal rats. &P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding values of BDL rats.

Table 2.

Measurement of IBDM in the experimental groups of animals

| Treatments | IBDM, % |

|---|---|

| Male | |

| Normal | 0.26 ± 0.04 |

| BDL | 6.32 ± 0.67a |

| BDL testosterone | 10.4 ± 0.80b |

| BDL + antitestosterone antibody | 1.8 ± 0.14b |

| BDL + castration | 0.32 ± 0.04b |

| BDL + castration + testosterone | 5.48 ± 0.63 |

| Female | |

| Normal | 0.77 ± 0.14 |

| BDL | 4.01 ± 0.21a |

| BDL + testosterone | 6.68 ± 0.89b |

Values are means ± SE. IBDM, intrahepatic bile duct mass. P < 0.05 vs. IBDM of normal rats (a) and vs. IBDM of BDL rats (b).

Castration inhibits secretin-stimulated cAMP levels and bile secretion.

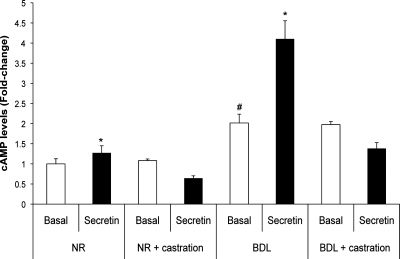

Secretin increased cAMP levels of cholangiocytes from normal but not normal castrated rats (Fig. 3). Basal cAMP levels of cholangiocytes from BDL rats were higher than cAMP levels of normal cholangiocytes (Fig. 3). As expected (3, 35), secretin did not induce changes in bile and bicarbonate secretion in normal rats with or without castration (Table 3). In agreement with previous studies (2, 3), in BDL rats (without castration), secretin increased cAMP levels in purified cholangiocytes (Fig. 3) and bicarbonate-rich choleresis in bile fistula rats (Table 2). After castration to BDL rats, the stimulatory effects of secretin on cAMP levels in purified cholangiocytes (Fig. 3) and bile and bicarbonate secretion in bile fistula rats (Table 2) were ablated. Chronic administration (1 wk) of testosterone to BDL castrated rats restored the functional secretory activity of cholangiocytes, since secretin was able to stimulate bile and bicarbonate secretion (Table 3) in these rats.

Fig. 3.

Measurement of basal and secretin-stimulated cAMP levels in purified cholangiocytes. In normal and BDL rats (without castration), secretin increases cAMP levels of purified cholangiocytes. In purified cholangiocytes from normal and BDL castrated rats, there was ablation of the stimulatory effects of secretin on cAMP levels. *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding basal cAMP levels. #P < 0.05 vs. basal cAMP levels of normal cholangiocytes. Data are means ± SE of 6 experiments.

Table 3.

Measurement of basal and secretin-stimulated bile flow, bicarbonate concentration and secretion in normal and rats that (immediately after BDI) underwent castration surgery followed by the administration of vehicle or testosterone

| Bile Flow |

Bicarbonate Concentration |

Bicarbonate Secretion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Basal, μl·min−1·kg body wt−1 | Secretin, μl·min−1·kg body wt−1 | Basal, meq/l | Secretin, meq/l | Basal, μl·min−1·kg body wt−1 | Secretin, μl·min−1·kg body wt−1 |

| Normal rats (n = 4) | 81.7 ± 6.3 | 83.0 ± 5.8 | 29.4 ± 0.9 | 26.8 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| Normal rats + castration (n = 4) | 70.2 ± 4.3 | 71.1 ± 8.9 | 30.7 ± 3.7 | 27.5 ± 6.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| BDI rats (n = 4) | 126.8 ± 15.0a | 187.8 ± 21.9b | 37.1 ± 3.4a | 45.5 ± 2.6b | 4.9 ± 0.2a | 8.6 ± 1.1b |

| BDI rats + castration + vehicle (n = 4) | 114.1 ± 24.7 | 133.0 ± 15.7ns | 26.8 ± 11.2 | 35.1 ± 14.9ns | 3.1 ± 1.8 | 4.9 ± 2.2ns |

| BDI rats + castration + testosterone (n = 4) | 109.1 ± 13.3c | 146.3 ± 13.9c | 32.5 ± 0.8 | 41.1 ± 1.1c | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 6.1 ± 0.6c |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of rats. BDI, bile duct incannulated.When steady spontaneous bile flow was reached [60-70 min from the infusion of Krebs-Ringer-Henseleit (KRH)], rats were infused for 30 min with secretin followed by a final infusion of KRH for 30 min. After the rats were surgically prepared for bile flow experiments, bile was collected every 10 min in preweighed tubes and used for determining bicarbonate concentration.

P < 0.05 vs. corresponding basal value of bile flow, bicarbonate concentration, or bicarbonate secretion of normal rats without castration.

P < 0.05 vs. corresponding basal value of bile flow, bicarbonate concentration. or bicarbonate secretion of BDI rats.

Vs. corresponding basal value of bile flow, bicarbonate concentration, or bicarbonate secretion of BDI rats without castration.

P < 0.05 vs. corresponding basal value of bile flow, bicarbonate concentration, or bicarbonate secretion of BDI castrated rats treated with testosterone for 1 wk. Differences between groups were analyzed by the Student's unpaired t-test when two groups were analyzed and ANOVA when more than two groups were analyzed.

Expression of 17β-HSD3 in liver sections and cholangiocytes: Evaluation of testosterone secretion in NRICC and determination of the effect of pharmacological inhibition and molecular silencing of 17β-HSD3 on NRICC growth.

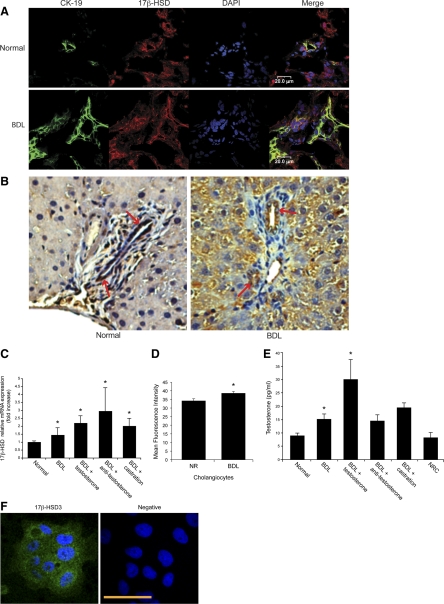

By immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry in liver sections, 17β-HSD3 was expressed by intrahepatic bile ducts from normal and BDL male rats (Fig. 4, A and B). The immunoreactivity was higher in bile ducts from male BDL rats compared with their corresponding normal rats. mRNA (by real-time PCR) and protein (by FACS) for 17β-HSD3 was expressed by normal male cholangiocytes and increased following BDL (Fig. 4, C and D). In purified cholangiocytes from male BDL rats with castration or receiving antitestosterone antibody, the expression of 17β-HSD3 mRNA was similar to or higher than that of BDL cholangiocytes (Fig. 4C), which is likely due to a compensatory mechanism by cholangiocytes in response to decreased testosterone serum levels after castration or the administration of antitestosterone antibody to BDL rats. We have also demonstrated that normal cholangiocytes and NRICC secrete testosterone in the supernatant, and the levels of testosterone increased in the supernatant of BDL cholangiocytes compared with normal cholangiocyte supernatant (Fig. 4E). In purified cholangiocytes from BDL rats with castration or receiving antitestosterone antibody, the secretion of testosterone was similar to that of BDL cholangiocytes (Fig. 4E). By immunofluorescence, NRICC express the protein for 17β-HSD3 (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

A: by immunofluorescence, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 (17β-HSD3) was expressed by intrahepatic bile ducts of liver sections from normal and BDL rats with and without castration. Colocalization with CK-19 (green staining) of bile ducts expressing the AR (red staining) is also visible. Bar = 50 μm. B: by immunohistochemistry, cholangiocytes from normal and BDL rats express 17β-HSD3. Original magnification, ×40. The immunoreactivity was higher in bile ducts from male BDL rats (++) compared with their corresponding normal rats (+). C and D: the message and protein for 17β-HSD3 was expressed by normal male cholangiocytes and increased following BDL. Data are means ± SE of 3 real-time PCR and FACS experiments. C: in purified cholangiocytes from BDL rats with castration or receiving antitestosterone antibody, the expression of 17β-HSD3 mRNA was similar to that of BDL cholangiocytes. Data are means ± SE of 3 real-time PCR experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. all of the other groups. D: the protein expression levels of 17β-HSD3 were determined by FACS analysis. *P < 0.05 vs. normal rat. E: normal cholangiocytes and NRICC secrete testosterone in the supernatant. The levels of testosterone increased in the supernatant of BDL cholangiocytes compared with normal cholangiocyte supernatant. In purified cholangiocytes from BDL rats with castration or receiving antitestosterone antibody, the secretion of testosterone was similar to that of BDL cholangiocytes. Data are means ± SE of 8 evaluations. *P < 0.05 vs. all of the other groups. F: by immunofluorescence, NRICC express the protein for 17β-HSD3. Bar = 50 μm.

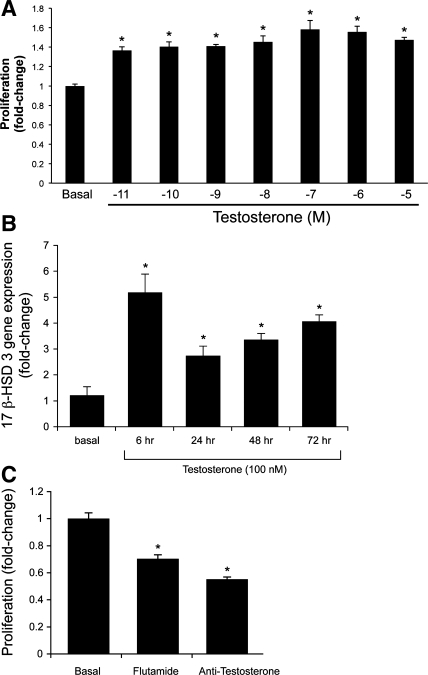

Similar to what is shown in vivo (Table 2), testosterone (10−11 to 10−5 M) in vitro increased the proliferation (by MTS) of NRICC compared with the corresponding basal value (Fig. 5A). Also, testosterone (100 nM) increased the mRNA expression of 17β-HSD3 (the key enzyme regulating testosterone synthesis) (20) in NRICC compared with the corresponding basal value (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the concept that testosterone (synthesized and secreted by freshly isolated cholangiocytes and NRICC) regulates the growth of these cells by an autocrine mechanism, we have shown that, when NRICC were incubated with flutamide (a specific antagonist of AR) (28) or antitestosterone antibody for 48 h, there was a decrease in cell growth compared with NRICC treated with 0.2% BSA (basal) (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, knock down of 17β-HSD3 (80% decrease by real-time PCR) (Fig. 6A) in NRICC decreased the basal proliferative activity of NRICC (Fig. 6B), supporting the concept that testosterone is an autocrine factor sustaining biliary growth.

Fig. 5.

A: measurement of NRICC proliferation following treatment with 0.2% BSA or testosterone. Testosterone (10−11 to 10−5 M) in vitro increased the proliferation (by MTS) of NRICC compared with the corresponding basal value. Data are means ± SE of 6 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding basal value. B: testosterone in vitro increased the mRNA expression of 17β-HSD3 (the key enzyme regulating testosterone synthesis) in NRICC compared with the corresponding basal value. Data are means ± SE of 6 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding basal value. C: measurement of cell growth (by MTS assays) in NRICC stimulated with BSA (basal), flutamide (a specific antagonist of AR), or antitestosterone antibody for 48 h. When NRICC were incubated with flutamide or antitestosterone antibody, there was a decrease in cell growth compared with NRICC treated with BSA. Data are means ± SE of 6 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding basal value.

Fig. 6.

A and B: effect of knock down of 17β-HSD3 on the basal proliferative activity of NRICC by MTS assays. Knock down of 17β-HSD3 (∼80%) in NRICC (A) decreased the proliferative activity of NRICC (B), supporting the concept that testosterone is an autocrine factor sustaining biliary growth. Data are means ± SE of 6 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding basal value.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates the paracrine and autocrine role of testosterone in the stimulation of cholangiocyte growth in normal and cholestatic states. We first demonstrated that intrahepatic bile ducts and hepatocytes (in liver sections) and freshly isolated cholangiocytes and hepatocytes from normal and BDL rats, and male NRICC express testosterone receptors. We have also shown that: 1) testosterone serum levels were lower in female and male BDL compared with normal rats and 2) castration and administration of neutralizing antitestosterone antibody significantly decreased testosterone serum levels in normal and BDL male rats. The administration of testosterone increased testosterone serum levels in both normal and BDL male rats and partly prevented castration-induced reduction of testosterone serum levels. We have also demonstrated that: 1) testosterone increased IBDM of both normal and BDL female and male rats; 2) castration and administration of antitestosterone antibody decreased IBDM in BDL male rats; and 3) administration of testosterone partly prevented castration-induced loss of IBDM in BDL male rats. At the functional level, in BDL castrated rats, there was ablation of secretin-stimulated cAMP levels and bicarbonate-rich choleresis, two functional indexes of biliary growth (2, 3, 22, 36). Similar to in vivo, in in vitro studies, we have demonstrated that testosterone increased the proliferation of male NRICC. We have also shown that: 1) intrahepatic cholangiocytes and NRICC express 17β-HSD3 (the key enzyme regulating testosterone synthesis) (20) and secrete testosterone; 2) the biliary expression of 17β-HSD3 and secretion of testosterone increases after BDL and in NRICC after in vitro treatment with testosterone; and 3) stable transfection of 17β-HSD3 in NRICC decreases the proliferative activity of these cells. The finding that testosterone stimulates biliary proliferation by an autocrine mechanism may be an important compensatory mechanism for sustaining biliary growth and ductal secretory activity in ductopenic pathologies of the biliary epithelium.

Cholangiopathies, which specifically target cholangiocytes, are characterized by dysregulation of the balance between biliary growth/damage (5). Thus, studies aimed to understand the intracellular mechanisms of this phenomenon are necessary. In this context, the cholestatic BDL rodent model has been used widely to pinpoint the mechanisms of biliary growth/apoptosis (2, 3, 6, 18, 19, 22, 34, 49). A number of studies have demonstrated that 1) gastrointestinal and sex hormones, bioagenic amines, and neuropeptides regulate the growth of bile ducts and 2) in the course of chronic cholestasis, cholangiocytes acquire neuroendocrine phenotypes regulating biliary functions by both autocrine and paracrine pathways (2, 3, 5–8, 18, 19, 22, 34, 49). Our study provides the first evidence that ARs are expressed by cholangiocytes and testosterone stimulates biliary growth and secretion during cholestasis. We propose that testosterone is important in sustaining biliary proliferation and ductal secretory activity in pathological conditions associated with functional damage of the biliary epithelium.

We first demonstrated in male rats the expression of functional testosterone receptors in bile ducts, cholangiocytes, hepatocytes, and NRICC. Supporting our findings, a number of studies have shown the presence of functional ARs in liver cells, including hepatocytes and bile ducts from PBC patients (26, 29, 38). Also, the AR mRNA has been detected in human liver biopsy samples, fetal liver, and HepG2 cells (48). In the next sets of experiments, we demonstrated that enhanced testosterone serum levels correlate with increased IBDM in male rats and decreased testosterone serum levels are associated with reduction of the number of intrahepatic bile ducts in male rats. We first validated our models, demonstrating that testosterone serum levels decreased in cholestatic BDL male rats (compared with normal rats) and in castrated rats and increased in rats chronically treated with testosterone. The decrease in testosterone serum levels is likely due to hypotrophy of seminal vesicles as observed in rats during puberty and BDL-induced cholestasis (33, 54, 57). Testicular atrophy has been observed in cirrhotic patients (52), whereas lower serum testosterone levels have been shown in patients with PBC (14). Contrasting results exist regarding serum testosterone levels in other liver diseases. For example, while a study has demonstrated lowered serum testosterone levels in cirrhotic rats (53), other studies have shown elevated serum testosterone may promote the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis (50). The decrease in serum testosterone levels observed in our animals is supported by a number of studies in rodents (31, 55) in which the decrease is prevented by the chronic administration of testosterone (55). Similar to our finding, other studies have demonstrated that chronic administration of testosterone increased testosterone serum levels (9). A number of studies have shown that sex hormones, including estrogens, prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone, and progesterone, sustain biliary proliferation by both paracrine and autocrine mechanisms (6, 7, 23, 39, 49). However, no information exists regarding the role of testosterone in modulating the balance between cholangiocyte growth/loss. The fact that testosterone increases biliary hyperplasia and prevents the loss of biliary growth and function (following castration) supports the concept that androgens can be important for ameliorating the cholestatic conditions associated with testicular hypotrophy and ductopenic conditions associated with decreased testosterone levels as occurs in PBC (14). These findings and the fact that the administration of neutralizing antitestosterone antibody reduces testosterone serum levels and biliary hyperplasia introduce the concept that the administration of testosterone receptor antagonists or antitestosterone antibodies may be new therapeutic approaches for decreasing the aberrant growth of cholangiocytes. At the functional level, we demonstrated that the decrease in testosterone serum levels was associated with ablation of secretin-stimulated cAMP synthesis in cholangiocytes and bicarbonate-rich choleresis in bile fistula male rats, two functional parameters that were restored by the chronic administration of testosterone. Indeed, enhanced secretin receptor expression and secretin-stimulated ductal secretory activity is associated with enhanced biliary hyperplasia (2, 3, 22), whereas reduced secretory capacity in response to secretin is an index of functional cholangiocyte damage (34, 36).

We next performed experiments in male rats aimed at demonstrating that: 1) purified cholangiocytes and NRICC express 17β-HSD3 (the key enzyme regulating testosterone synthesis) (20) and secrete testosterone and 2) testosterone stimulates in vitro the growth of NRICC by directly interacting with ARs on cholangiocytes by an autocrine mechanism stimulating the expression of 17β-HSD3. The higher expression of 17β-HSD3 and the enhanced secretion of testosterone by purified cholangiocytes from BDL rats and BDL rats treated in vivo with testosterone (that proliferate at higher rates) support the concept that testosterone (secreted by cholangiocytes) is a trophic autocrine hormone for sustaining biliary hyperplasia. The concept that testosterone stimulates biliary growth by an autocrine fashion is also supported by the fact that testosterone increases the mRNA expression of 17β-HSD3 in vitro in NRICC and flutamide (a specific antagonist of AR) and antitestosterone antibody inhibit the growth of NRICC in vitro. Conclusive evidence that testosterone is an important autocrine trophic factor sustaining biliary growth is also supported by the finding that, in conditions of lowered serum testosterone levels (after castration and administration of neutralizing antitestosterone antibody to BDL rats), there is enhanced testosterone secretion likely by a compensatory mechanism. The possible role of testosterone as a key autocrine trophic was also supported by knock down of 17β-HSD3, which caused a marked decreased in NRICC proliferation. In support of our findings, a number of studies demonstrate the presence of 17β-HSD3 in the liver (41) and show that this enzyme isoform modulates the stimulatory effects on the mitosis of a number of cells, including cholangiocytes. This idea is supported by recent studies showing that specific inhibitors of 17β-HSD3 have been shown to inhibit hormone-dependent prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia (12). The novel concept that cholangiocytes are secretory cells synthesizing a number of factors (including testosterone) regulating the homeostasis of the biliary epithelium is supported by a number of studies. For example, cholangiocytes synthesize a number of neuroendocrine factors, such progesterone, prolactin, vascular endothelial growth factor, and nerve growth factor, that stimulate biliary growth (19, 21, 23, 49). Also, serotonin inhibits biliary hyperplasia in BDL rats, since cholangiocytes secrete serotonin, the blockage of which enhances cholangiocyte proliferation in the course of cholestasis (42).

In summary, we have demonstrated the presence of functional ARs on cholangiocytes and that testosterone stimulates biliary growth by an autocrine mechanism by increasing the expression of 17β-HSD3 in cholangiocytes. We have also demonstrated that testosterone prevents the decrease in biliary hyperplasia typical of BDL after castration and the administration of neutralizing antitestosterone antibody. We propose that drug targeting of 17β-HSD3 may be important to regulate the balance between biliary proliferation/loss and ductal secretory activity in cholangiopathies.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases RO1 Grant DK-081442 awarded to S. Glaser and Yale Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center Grant U24 DK-76169. This work was partly supported by the Dr. Nicholas C. Hightower Centennial Chair of Gastroenterology from Scott & White to Dr. G. Alpini, Research Programmes of Significant National Interest funds 2005–2007 from the Italian Ministro dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricera, Faculty funds from Rome University “La Sapienza” to E. Gaudio, and by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants (from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan) for the Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (21590822) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to Y. Ueno.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. G. Alpini for the isolation of cholangiocytes and hepatocytes and constructive suggestions during the development of the project, Anna Webb and the Texas A&M Health Science Center Microscopy Imaging Center for their assistance with microscopy, Bryan Moss, Medical Illustration, Scott & White, and the Animal Facility at Scott & White and Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alpini G, Glaser S, Robertson W, Phinizy JL, Rodgers RE, Caligiuri A, LeSage G. Bile acids stimulate proliferative and secretory events in large but not small cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 273: G518– G529, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alpini G, Glaser S, Ueno Y, Pham L, Podila PV, Caligiuri A, LeSage G, LaRusso NF. Heterogeneity of the proliferative capacity of rat cholangiocytes after bile duct ligation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 274: G767– G775, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alpini G, Lenzi R, Sarkozi L, Tavoloni N. Biliary physiology in rats with bile ductular cell hyperplasia. Evidence for a secretory function of proliferated bile ductules. J Clin Invest 81: 569– 578, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alpini G, Phinizy JL, Glaser S, Francis H, Benedetti A, Marucci L, LeSage G. Development and characterization of secretin-stimulated secretion of cultured rat cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G1066– G1073, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alpini G, Prall RT, LaRusso NF. The pathobiology of biliary epithelia. The Liver; Biology & Pathobiology (4th ed.), edited by Arias IM, Boyer JL, Chisari FV, Fausto N, Jakoby W, Schachter D, Shafritz DA. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins, 2001, p. 421–435 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alvaro D, Alpini G, Onori P, Franchitto A, Glaser S, Le Sage G, Gigliozzi A, Vetuschi A, Morini S, Attili AF, Gaudio E. Effect of ovariectomy on the proliferative capacity of intrahepatic rat cholangiocytes. Gastroenterology 123: 336– 344, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alvaro D, Alpini G, Onori P, Perego L, Svegliata Baroni G, Franchitto A, Baiocchi L, Glaser S, Le Sage G, Folli F, Gaudio E. Estrogens stimulate proliferation of intrahepatic biliary epithelium in rats. Gastroenterology 119: 1681– 1691, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alvaro D, Mancino MG, Glaser S, Gaudio E, Marzioni M, Francis H, Alpini G. Proliferating cholangiocytes: a neuroendocrine compartment in the diseased liver. Gastroenterology 132: 415– 431, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Angelsen A, Falkmer S, Sandvik AK, Waldum HL. Pre- and postnatal testosterone administration induces proliferative epithelial lesions with neuroendocrine differentiation in the dorsal lobe of the rat prostate. Prostate 40: 65– 75, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arenas MI, Perez-Marquez J. Cloning, expression, and regulation by androgens of a putative member of the oxytocinase family of proteins in the rat prostate. Prostate 53: 218– 224, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang CS, Kokontis J, Liao ST. Structural analysis of complementary DNA and amino acid sequences of human and rat androgen receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 7211– 7215, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Day JM, Tutill HJ, Foster PA, Bailey HV, Heaton WB, Sharland CM, Vicker N, Potter BV, Purohit A, Reed MJ. Development of hormone-dependent prostate cancer models for the evaluation of inhibitors of 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3. Mol Cell Endocrinol 301: 251– 258, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeMorrow S, Francis H, Gaudio E, Ueno Y, Venter J, Onori P, Franchitto A, Vaculin B, Vaculin S, Alpini G. Anandamide inhibits cholangiocyte hyperplastic proliferation via activation of thioredoxin 1/redox factor 1 and AP-1 activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G506– G519, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Floreani A, Paternoster D, Mega A, Farinati F, Plebani M, Baldo V, Grella P. Sex hormone profile and endometrial cancer risk in primary biliary cirrhosis: a case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 103: 154– 157, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fort P, Marty L, Piechaczyk M, el Sabrouty S, Dani C, Jeanteur P, Blanchard JM. Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase multigenic family. Nucleic Acids Res 13: 1431– 1442, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Francis H, Glaser S, DeMorrow S, Gaudio E, Ueno Y, Venter J, Dostal D, Onori P, Franchitto A, Marzioni M, Vaculin S, Vaculin B, Katki K, Stutes M, Savage J, Alpini G. Small mouse cholangiocytes proliferate in response to H1 histamine receptor stimulation by activation of the IP3/CaMK I/CREB pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C499– C513, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Francis H, Glaser S, Ueno Y, LeSage G, Marucci L, Benedetti A, Taffetani S, Marzioni M, Alvaro D, Venter J, Reichenbach R, Fava G, Phinizy JL, Alpini G. cAMP stimulates the secretory and proliferative capacity of the rat intrahepatic biliary epithelium through changes in the PKA/Src/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. J Hepatol 41: 528– 537, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Francis H, Onori P, Gaudio E, Franchitto A, DeMorrow S, Venter J, Kopriva S, Carpino G, Mancinelli R, White M, Meng F, Vetuschi A, Sferra R, Alpini G. H3 histamine receptor-mediated activation of protein kinase Calpha inhibits the growth of cholangiocarcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Res 7: 1704– 1713, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaudio E, Barbaro B, Alvaro D, Glaser S, Francis H, Ueno Y, Meininger CJ, Franchitto A, Onori P, Marzioni M, Taffetani S, Fava G, Stoica G, Venter J, Reichenbach R, De Morrow S, Summers R, Alpini G. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates rat cholangiocyte proliferation via an autocrine mechanism. Gastroenterology 130: 1270– 1282, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geissler WM, Davis DL, Wu L, Bradshaw KD, Patel S, Mendonca BB, Elliston KO, Wilson JD, Russell DW, Andersson S. Male pseudohermaphroditism caused by mutations of testicular 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3. Nat Genet 7: 34– 39, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gigliozzi A, Alpini G, Baroni GS, Marucci L, Metalli VD, Glaser S, Francis H, Mancino MG, Ueno Y, Barbaro B, Benedetti A, Attili AF, Alvaro D. Nerve growth factor modulates the proliferative capacity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium in experimental cholestasis. Gastroenterology 127: 1198– 1209, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glaser S, Benedetti A, Marucci L, Alvaro D, Baiocchi L, Kanno N, Caligiuri A, Phinizy JL, Chowdury U, Papa E, LeSage G, Alpini G. Gastrin inhibits cholangiocyte growth in bile duct-ligated rats by interaction with cholecystokinin-B/Gastrin receptors via d-myo-inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate-, Ca(2+)-, and protein kinase C alpha-dependent mechanisms. Hepatology 32: 17– 25, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glaser S, DeMorrow S, Francis H, Ueno Y, Gaudio E, Vaculin S, Venter J, Franchitto A, Onori P, Vaculin B, Marzioni M, Wise C, Pilanthananond M, Savage J, Pierce L, Mancinelli R, Alpini G. Progesterone stimulates the proliferation of female and male cholangiocytes via autocrine/paracrine mechanisms. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G124– G136, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24. Glaser S, Lam IP, Franchitto A, Gaudio E, Onori P, Chow BK, Wise C, Kopriva S, Venter J, White M, Ueno Y, Dostal D, Carpino G, Mancinelli R, Butler W, Chiasson V, DeMorrow S, Francis H, Alpini G. Knockout of secretin receptor reduces large cholangiocyte hyperplasia in mice with extrahepatic cholestasis induced by bile duct ligation. Hepatology 52: 204– 214, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glaser SS, Gaudio E, Rao A, Pierce LM, Onori P, Franchitto A, Francis HL, Dostal DE, Venter JK, DeMorrow S, Mancinelli R, Carpino G, Alvaro D, Kopriva SE, Savage JM, Alpini GD. Morphological and functional heterogeneity of the mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Lab Invest 89: 456– 469, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hinchliffe SA, Woods S, Gray S, Burt AD. Cellular distribution of androgen receptors in the liver. J Clin Pathol 49: 418– 420, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishii M, Vroman B, LaRusso NF. Isolation and morphologic characterization of bile duct epithelial cells from normal rat liver. Gastroenterology 97: 1236– 1247, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jin H, Lin J, Fu L, Mei YF, Peng G, Tan X, Wang DM, Wang W, Li YG. Physiological testosterone stimulates tissue plasminogen activator and tissue factor pathway inhibitor and inhibits plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 release in endothelial cells. Biochem Cell Biol 85: 246– 251, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jorge AD, Stati AO, Roig LV, Ponce G, Jorge OA, Ciocca DR. Steroid receptors and heat-shock proteins in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 18: 1108– 1114, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kanno N, LeSage G, Glaser S, Alpini G. Regulation of cholangiocyte bicarbonate secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G612– G625, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kashiwagi B, Shibata Y, Ono Y, Suzuki R, Honma S, Suzuki K. Changes in testosterone and dihydrotestosterone levels in male rat accessory sex organs, serum, and seminal fluid after castration: establishment of a new highly sensitive simultaneous androgen measurement method. J Androl 26: 586– 591, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kato A, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF. Secretin stimulates exocytosis in isolated bile duct epithelial cells by a cyclic AMP-mediated mechanism. J Biol Chem 267: 15523– 15529, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kiani S, Valizadeh B, Hormazdi B, Samadi H, Najafi T, Samini M, Dehpour AR. Alteration in male reproductive system in experimental cholestasis: roles for opioids and nitric oxide overproduction. Eur J Pharmacol 615: 246– 251, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. LeSage G, Alvaro D, Benedetti A, Glaser S, Marucci L, Baiocchi L, Eisel W, Caligiuri A, Phinizy JL, Rodgers R, Francis H, Alpini G. Cholinergic system modulates growth, apoptosis, and secretion of cholangiocytes from bile duct-ligated rats. Gastroenterology 117: 191– 199, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. LeSage G, Glaser S, Gubba S, Robertson WE, Phinizy JL, Lasater J, Rodgers RE, Alpini G. Regrowth of the rat biliary tree after 70% partial hepatectomy is coupled to increased secretin-induced ductal secretion. Gastroenterology 111: 1633– 1644, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. LeSage G, Glaser S, Marucci L, Benedetti A, Phinizy JL, Rodgers R, Caligiuri A, Papa E, Tretjak Z, Jezequel AM, Holcomb LA, Alpini G. Acute carbon tetrachloride feeding induces damage of large but not small cholangiocytes from BDL rat liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G1289– G1301, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luu-The V, Belanger A, Labrie F. Androgen biosynthetic pathways in the human prostate. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 22: 207– 221, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ma WL, Hsu CL, Wu MH, Wu CT, Wu CC, Lai JJ, Jou YS, Chen CW, Yeh S, Chang C. Androgen receptor is a new potential therapeutic target for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 135: 947– 955, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mancinelli R, Onori P, Gaudio E, DeMorrow S, Franchitto A, Francis H, Glaser S, Carpino G, Venter J, Alvaro D, Kopriva S, White M, Kossie A, Savage J, Alpini G. Follicle-stimulating hormone increases cholangiocyte proliferation by an autocrine mechanism via cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Elk-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G11– G26, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40. Marcantonio D, Chalifour LE, Alaoui J MAHTH, Alaoui-Jamali MA, Huynh HT. Steroid-sensitive gene-1 is an androgen-regulated gene expressed in prostatic smooth muscle cells in vivo. J Mol Endocrinol 26: 175– 184, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martel C, Rheaume E, Takahashi M, Trudel C, Couet J, Luu-The V, Simard J, Labrie F. Distribution of 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene expression and activity in rat and human tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 41: 597– 603, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marzioni M, Glaser S, Francis H, Marucci L, Benedetti A, Alvaro D, Taffetani S, Ueno Y, Roskams T, Phinizy JL, Venter J, Fava G, LeSage G, Alpini G. Autocrine/paracrine regulation of the growth of the biliary tree by the neuroendocrine hormone serotonin. Gastroenterology 128: 121– 137, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McLachlan RI, Wreford NG, O'Donnell L, de Kretser DM, Robertson DM. The endocrine regulation of spermatogenesis: independent roles for testosterone and FSH. J Endocrinol 148: 1– 9, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ohnishi S, Murakami T, Moriyama T, Mitamura K, Imawari M. Androgen and estrogen receptors in hepatocellular carcinoma and in the surrounding noncancerous liver tissue. Hepatology 6: 440– 443, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Onori P, Wise C, Gaudio E, Franchitto A, Francis H, Carpino G, Lee V, Lam I, Miller T, Dostal DE, Glaser S. Secretin inhibits cholangiocarcinoma growth via dysregulation of the cAMP-dependent signaling mechanisms of secretin receptor. Int J Cancer 127: 43– 54, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rutenburg AM, Kim H, Fischbein JW, Hanker JS, Wasserkrug HL, Seligman AM. Histochemical and ultrastructural demonstration of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase activity. J Histochem Cytochem 17: 517– 526, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shidham VB, Komorowski RA, Machhi JK. Androgen receptor expression in metastatic adenocarcinoma in females favors a breast primary (Abstract). Diagn Pathol 1: 34, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stubbs AP, Engelman JL, Walker JI, Faik P, Murphy GM, Wilkinson ML. Measurement of androgen receptor expression in adult liver, fetal liver, and Hep-G2 cells by the polymerase chain reaction. Gut 35: 683– 686, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Taffetani S, Glaser S, Francis H, DeMorrow S, Ueno Y, Alvaro D, Marucci L, Marzioni M, Fava G, Venter J, Vaculin S, Vaculin B, Lam IP, Lee VH, Gaudio E, Carpino G, Benedetti A, Alpini G. Prolactin stimulates the proliferation of normal female cholangiocytes by differential regulation of Ca2+-dependent PKC isoforms (Abstract). BMC Physiol 7: 6, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tanaka K, Sakai H, Hashizume M, Hirohata T. Serum testosterone:estradiol ratio and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma among male cirrhotic patients. Cancer Res 60: 5106– 5110, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsai-Morris CH, Khanum A, Tang PZ, Dufau ML. The rat 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type III: molecular cloning and gonadotropin regulation. Endocrinology 140: 3534– 3542, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsega E, Nordenfelt E, Hansson BG, Mengesha B, Lindberg J. Chronic liver disease in Ethiopia: a clinical study with emphasis on identifying common causes. Ethiop Med J 30: 1– 33, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van der Merwe SW, van den Bogaerde JB, Goosen C, Maree FF, Milner RJ, Schnitzler CM, Biscardi A, Mesquita JM, Engelbrecht G, Kahn D, Fevery J. Hepatic osteodystrophy in rats results mainly from portasystemic shunting. Gut 52: 580– 585, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Zajko AB, Cobb CF. Consequences of complete bile-duct ligation on the pubertal process in the male rat. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 4: 616– 621, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ward GR, Abdel-Rahman AA. Effect of testosterone replacement or duration of castration on baroreflex bradycardia in conscious rats (Abstract). BMC Pharmacol 5: 9, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weibel ER, Staubli W, Gnagi HR, Hess FA. Correlated morphometric and biochemical studies on the liver cell. I. Morphometric model, stereologic methods, and normal morphometric data for rat liver. J Cell Biol 42: 68– 91, 1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yoshioka K, Sasaki M, Imai S, Tsujio M, Taniguchi K, Mutoh K. Testicular atrophy after bile duct ligation in chickens. Vet Pathol 41: 68– 72, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]