Abstract

Chronic hypoxia activates transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling and leads to pulmonary vascular remodeling. Pharmacological activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) has been shown to prevent hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in rodent models, suggesting a vasoprotective effect of PPAR-γ under chronic hypoxic stress. This study tested the hypothesis that there is a functional interaction between TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway and PPAR-γ in isolated pulmonary artery small muscle cells (PASMCs) under hypoxic stress. We observed that chronic hypoxia led to a dramatic decrease of PPAR-γ protein expression in whole lung homogenates (rat and mouse) and hypertrophied pulmonary arteries and isolated PASMCs. Using a transgenic model of mouse with inducible overexpression of a dominant-negative mutant of TGF-β receptor type II, we demonstrated that disruption of TGF-β pathway significantly attenuated chronic hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ in lung. Similarly, in isolated rat PASMCs, antagonism of TGF-β signaling with either a neutralizing antibody to TGF-β or the selective TGF-β receptor type I inhibitor SB431542 effectively attenuated hypoxia-induced PPAR-γ downregulation. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that TGF-β1 treatment suppressed PPAR-γ expression in PASMCs under normoxia condition. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis showed that TGF-β1 treatment significantly increased binding of Smad2/3, Smad4, and the transcriptional corepressor histone deacetylase 1 to the PPAR-γ promoter in PASMCs. Conversely, treatment with the PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone attenuated TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix molecule expression and growth factor in PASMCs. These data provide strong evidence that activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling, via transcriptional suppression of PPAR-γ expression, mediates chronic hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ expression in lung.

Keywords: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, pulmonary vascular remodeling

chronic hypoxic stress results in pulmonary artery constriction, hypertension, and remodeling in human subjects and animal models (3). Characteristic features of chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension (PH) include neomuscularization of distal pulmonary arterioles, adventitial thickening of larger pulmonary arteries, perivascular extracellular matrix deposition, and hyperplasia and reduced apoptosis of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) (14, 30).

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and its Smad signaling pathway play an important role in the pathogenesis of PH (17, 27). Elevated levels of TGF-β expression and Smad2/3 phosphorylation have been reported in rat models of experimental PH in response to hypoxia or monocrotaline treatment, as well as in patients with idiopathic PH (1, 20, 29). On a cellular level, TGF-β has been shown to promote the proliferation and migration of PASMCs from rats and patients with PH and to increase extracellular matrix and endothelin-1 expression in rat and human PASMCs (14, 29). Furthermore, emerging evidence has implicated enhanced TGF-β signaling attributable to a loss of function mutation of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II in the pathogenesis of idiopathic PH in humans (26). In addition, we have demonstrated that disruption of TGF-β signaling by inducible overexpression of a dominant-negative mutant of TGF-β receptor type II (DnTGFβRII) significantly attenuated hypoxia-induced pulmonary artery remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy in mice (5), providing in vivo evidence for a functional role of TGF-β signaling in hypoxia adaptation.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) is a nuclear receptor that functions as a transcription factor to regulate a variety of biological processes, including hypertrophic, fibrotic, and inflammatory responses to stress (10, 22). Accumulating evidence has shown that treatment with PPAR-γ agonists, including rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, elicits antiproliferative, proapoptotic, and vasodilatory effects, improves endothelial function, and prevents chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling in rodent models (1, 6, 13, 24). Furthermore, transgenic mice with targeted deletion of PPAR-γ in SMCs or endothelial cells spontaneously develop right ventricular hypertrophy and increased muscularization of the distal pulmonary arteries (11). Together, these provocative findings suggest that PPAR-γ may act as an endogenous vasoprotective antiproliferative/fibrogenic factor in the process of chronic hypoxic-induced PH and pulmonary artery remodeling (32).

It has been shown that chronic hypoxia-induced PH and pulmonary artery remodeling are related to an imbalance in the normal counterregulatory relationships between mitogenic/extracellular matrix forming and antiproliferative/proapoptotic signaling pathways in lung and PASMCs (5, 17, 18). The current study extended these findings by linking TGF-β and PPAR-γ signaling in lung and PASMCs in the context of hypoxic stress. We demonstrate that hypoxia inhibits PPAR-γ protein expression in rat lung and isolated rat PASMCs via a TGF-β-dependent mechanism. We further observed that TGF-β mediates hypoxia-induced PPAR-γ downregulation by suppressing PPAR-γ expression at the transcriptional level. Conversely, pharmacological activation of PPAR-γ by the agonist rosiglitazone attenuated TGF-β-induced extracellular matrix expression in isolated PASMCs. These findings provide strong evidence for a counterregulatory relationship between TGF-β-Smad signaling and PPAR-γ expression in the pathogenesis of hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation and surgical procedures.

To test the hypothesis that chronic hypoxia leads to downregulation of PPAR-γ expression in rat pulmonary artery, adult (age 8 wk) male Sprague-Dawley rats, obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), were exposed to hypoxia (10% O2, 1 atm) in an 800-l model 818GBB Plexiglas glove box (Plas Laboratories, Lansing, MI) for 2 wk as previously described (5). Rats were fed a standard diet (Harlan-Teklad, Madison, WI) and were housed in rooms maintained at a constant humidity (60 ± 5%), temperature (24 ± 1°C), and light cycle (6:00 AM-6:00 PM). All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and were consistent with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (DHEW publication No. 96–01, revised in 2002). To test the effect of TGF-β signaling on PPAR-γ expression in lung under chronic hypoxic condition, adult (8–10 wk old) male C57BL6/J wild-type and transgenic mice with inducible overexpression of DnTGFβRII were exposed to hypoxia (10% O2, 1 atm) (1, 5, 21). DnTGFβRII mice were given drinking water with 25 mM ZnSO4 to activate the expression of the transgene 1 wk before the hypoxic exposure.

Immunohistochemical analysis.

To determine the level of PPAR-γ protein expression in pulmonary artery, lungs from 2 wk-hypoxia-adapted and air control rats were fixed in the distended state by infusion of 10% buffered formalin into the pulmonary artery and trachea at 100 and 25 mmHg pressure, respectively, for 1 min, then placed in a bath of 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, paraffin embedded, and sectioned for immunohistochemical analysis using a specific antibody against PPAR-γ (Millipore-Upstate, Temecula, CA) as previously described (5). The mean density of SMCs with positive PPAR-γ staining in whole pulmonary artery was calculated using light microscopy with a Qimaging QiCam digital camera (Qimaging, Burnaby, BC, Canada) interfaced with a computer system running Metamorph 6.2v4 software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA). A total of three lung sections/rat were blindly counted; six rats per group were examined.

PASMC isolation and culture.

To test directly the effects of hypoxia and of TGF-β on PPAR-γ protein and gene expression, isolated PASMCs were used. PASMCs were isolated from distal segments of rat pulmonary arteries (2nd-3rd branches, 0.1–0.2-mm external diameter) using the explant method described previously (17, 18). PASMCs were used for experiments at passages 3 or 4. Before each study, PASMCs were subjected to serum starvation for 24 h. To examine the effects of hypoxia on PPAR-γ protein expression, PASMCs were transferred into an air-tight hypoxic chamber (model 2710; Cell Culture Incubator; Queue Systems, Parkersville, WV) containing 1% O2-5% CO2-94% N2 as previously described (18). To examine the effects of TGF-β1 on PPAR-γ gene expression, PASMCs were pretreated with the selective TGF-β1 receptor type I inhibitor SB431542 (IC = 94 nM, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or a neutralizing monoclonal antibody against TGF-β1/2/3 (R&D Systems, San Diego, CA) for 1 h, and then exposed to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml, Sigma Aldrich) or incubated in the hypoxic chamber for an additional 24 h.

Western blotting analysis.

To detect the effects of hypoxia and TGF-β treatment on PPAR-γ protein expression, rat and mouse lungs were homogenized in a tissue protein extraction reagent, and cultured rat PASMCs were lysed by mammalian protein extraction reagent containing proteinase and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Proteins extracted from rat lung tissues or cultured PASMCs were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane as described previously (5, 19). Blots were probed with anti-PPAR-γ (Millipore-Upstate), anti-pSmad3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), anti-β-actin/anti-α-tubulin primary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, respectively. Bands were visualized by use of a Super Western Sensitivity Chemiluminescence Detection System (Pierce). Autoradiographs were quantitated by densitometry (NIH ImageJ). PPAR-γ protein levels were normalized using β-actin or α-tubulin as an internal standard.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

To determine the effects of TGF-β1 on PPAR-γ gene expression in PASMCs, serum-starved PASMCs were exposed to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 24 h. To test the effects of PPAR-γ agonist on the expression of TGF-β target genes, cells were pretreated with rosiglitazone (Rosi, 0.1 μM; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) for 24 h and then treated with TGF-β1 for an additional 12 h. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the purified RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified by real-time quantitative PCR using the SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a Bio-Rad iCycler with specific primers [PPAR-γ: 5′-AGC ATG GTG CCT TCG CTG ATG C-3′ and 5′-AAG TTG GTG GGC CAG AAT GGC A-3′; connective tissue growth factor (CTGF): 5′-GCT GTG AGG AGT GGG TGT-3′ and 5′-TTG GCT CGC ATC ATA GTT-3′; plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1): 5′-GCC CTA CCA CGG CGA AAC C-3′ and 5′-AGG ATG AGG AGG CGG GGC AG-3′; periostin: 5′-CCA GTG CTC TGA GGC TAT-3′ and 5′-TAC CAG GTC CGT GAA AGT-3′; osteopontin (OPN): 5′-GCT TGG CTT ACG GAC TGA-3′ and 5′-TGT TTC CAC GCT TGG TTC-3′; PDGF-BB: 5′-AAT CGC CGA GTG CAA GAC GCG-3′ and 5′- CGG CCA CAC CAG GAA GTT GGC-3′; 18S rRNA: 5′-GAA ACG GCT ACC ACA TCC-3′ and 5′-CAC CAG ACT TGC CCT CCA-3′]. Relative RNA levels were calculated using the iCycler software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and normalized using 18S rRNA.

PPAR-γ promoter activity analysis.

To test the hypothesis that TGF-β inhibits PPAR-γ promoter activity in PASMCs, quiescent PASMCs were transiently cotransfected with a pGL3-Basic plasmid containing a human PPAR-γ gene promoter (∼2.8 kb of the 5′-flanking region) fused with a firefly luciferase reporter gene and a pRL-TK plasmid containing a Renilla luciferase gene (as a control for transfection efficiency) using the Lipofectamine Plus Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen). One day after transfection, PASMCs were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) or vehicle for 24 h. PASMCs were harvested, and luminescence from transfected PASMCs was quantified by measuring firefly/Renilla luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis.

Quiescent PASMCs (1.8 × 107 cells per 150-mm dish) were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) or vehicle for 1 h, and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were carried out with anti-Smad2/3 (sc-8332, Santa Cruz), anti-Smad4 (sc-7154, Santa Cruz), anti-histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) (sc-7872, Santa Cruz) antibodies and normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027, Santa Cruz) as described previously (25). A pair of primers (5′- CTG CGT GAC AGT CAG GGC ACC -3′ and 5′- CGA CCC AAG AAG GTC CCA CGT-3′) were used to amplify a 70-bp fragment (−226 to −295 bp) of the promoter region of the rat PPAR-γ gene for detection of binding of Smad2/3, Smad4, and HDAC1. PCR was run at 29 to 31 cycles, and the PCR products were detected in agarose gel with ethidium bromide. Selective PCR product levels were semiquantitated using densitometry and normalized by respective input values.

Pulmonary arterial muscularization assessment.

Pulmonary arterial muscularization was assessed using α-smooth muscle actin-immunostained lung sections as described previously (7). Arterial muscularization was defined according to the degree of muscularization: muscularized arteries (with two distinct elastic laminae and complete medial coat), partially muscularized arteries (with a continuous external elastic lamina and an incomplete medial coat), and nonmuscularized vessels (with only one single elastic lamina but no VSMC apparent) were distinguished by observation and counted. The percentage of muscularization of each pulmonary artery relative to its size (25–200 μm in diameter) was calculated as an index of pulmonary arterial muscularization.

Cell migration assay.

To test the effect of Rosi and TGF-β on PASMC migration, serum-starved cells (0.5 × 105) were seed in Falcon cell culture inserts (cat. 35–3097; Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with 8.0-μm-pore size in 1% FBS-DMEM with vehicle or 0.1 μM Rosi; 0.5 ml 10% FBS-DMEM with vehicle or Rosi were added to the 24-well plates. After incubation for 3 h, cells were treated with vehicle or TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 12 h; the cells in the upper chamber and on the polyester-track-etched membrane were mechanically removed with a cotton swab and washed with ice-cold PBS. Cells adherent to the outer surface of the lower side of the membrane were fixed with methanol for 15 min and stained with hematoxylin for 20 s. Fifteen fields were randomly selected in each group and cells were counted.

Statistical analysis.

Results were expressed as means ± SE. Analyses were carried out using the SigmaStat statistical package (Jandel Scientific, San Rafeal, CA). Our primary statistical test was ANOVA; one-way ANOVA to evaluate the differences in mean values attributable to main effects (hypoxia, TGF-β1), and two-way ANOVA to test their interactions. If ANOVA results were significant, a post hoc comparison among groups was performed with the Newman-Keuls test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

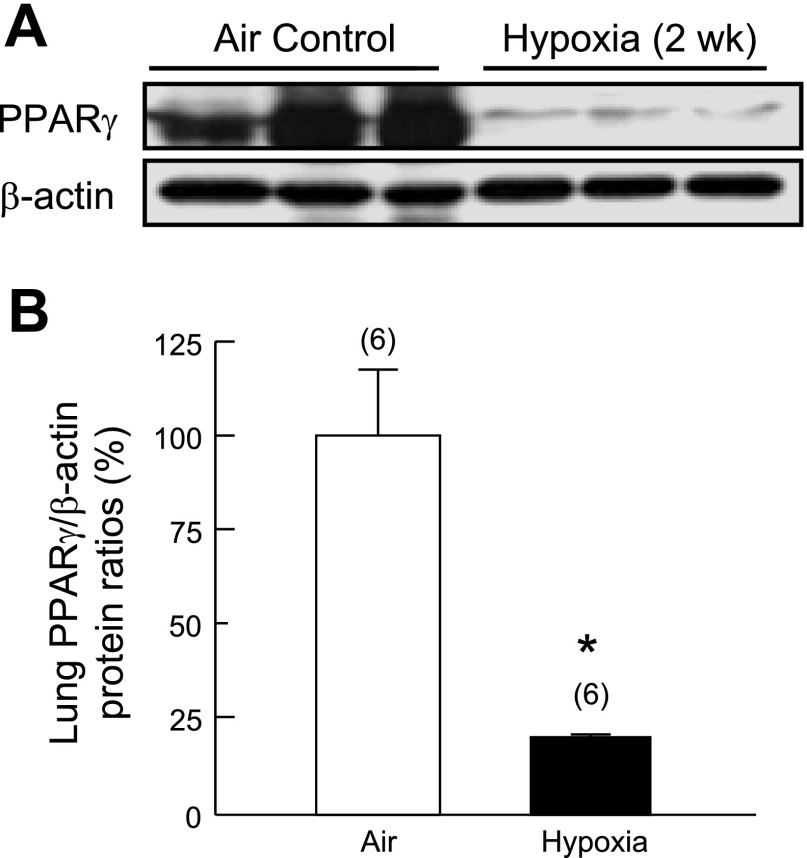

Chronic hypoxia decreases PPAR-γ protein expression in rat lung.

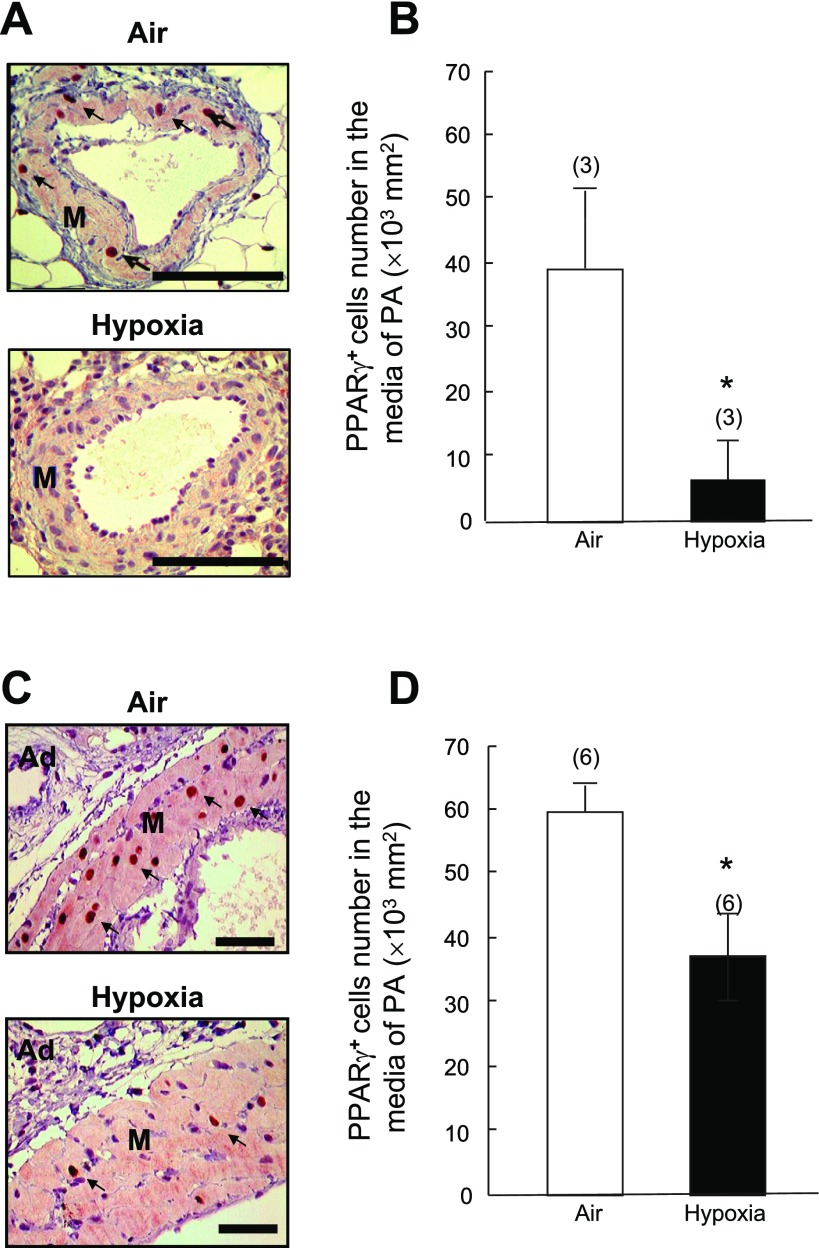

Two weeks of exposure to normobaric hypoxia led to a significant decrease (−77%) in PPAR-γ protein expression in rat whole lung tissue extracts, compared with air controls (Fig. 1, A and B). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that PPAR-γ was expressed ubiquitously in air control lungs, including in alveolar septal structures and adventitia and media in pulmonary artery (size from 250 μm to 750 μm) (Fig. 2). In contrast, PPAR-γ expression was greatly reduced in hypoxia-exposed lungs, particularly in the hypertrophied pulmonary arteries, as evidenced by decreased numbers of PPAR-γ-positive cells in medial PASMCs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Effects of 2 wk of hypoxia (10% O2, 1 atm) or air (control) on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) protein expression in rat lung. A: representative Western blot analysis of PPAR-γ and β-actin protein levels in the whole lung homogenates. B: PPAR-γ protein levels normalized using β-actin protein levels as an internal standard. *P < 0.05 vs. Air group.

Fig. 2.

Effects of 2 wk of hypoxia (10% O2, 1 atm) or air (control) on PPAR-γ protein expression in pulmonary arteries (PA). Representative micrographs of PPAR-γ-stained rat pulmonary arteries are shown. A: ∼250 μm in diameter. C: ∼750 μm in diameter (bar = 100 μm). B and D: bar graphs summarize the density of PPAR-γ-positive cells in smooth muscle media of pulmonary arteries (∼250 μm and ∼750 μm in diameter, respectively). Ad: adventitial tissue, M: smooth muscle media. Arrows: cells with positive PPAR-γ-staining. Results are means ± SE; n = number of rats. *P < 0.05 compared with respective air control groups.

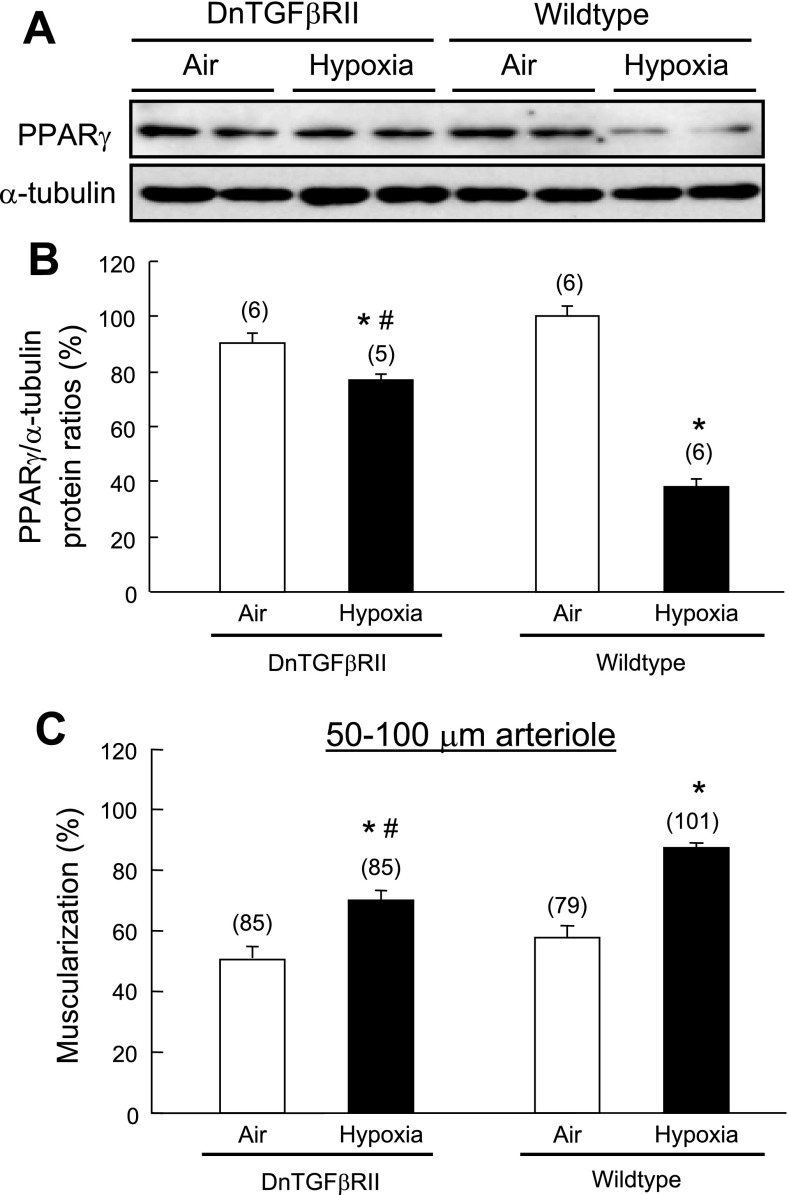

Blocking of TGF-β signaling significantly attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ expression in DnTGFβRII mice.

We have recently demonstrated that disruption of TGF-β signaling significantly alleviates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary arterial remodeling in DnTGFβRII mice (20). In the current study, we demonstrated that 2-wk chronic hypoxic exposure decreased PPAR-γ protein levels in lung of wild-type mouse (Fig. 3A). In contrast, hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ expression was significantly attenuated in DnTGFβRII mice when TGF-β signaling was blocked (Fig. 3B). Hypoxia-induced arteriolar muscularization in small pulmonary arteries (50–100 μm, an index of vascular remodeling) (Fig. 3C) and right ventricular hypertrophy (an index of pulmonary hypertension) (Table 1) were less marked in DnTGFβRII than that in wild-type mice. These results suggest that TGF-β has a dominant role in hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ expression, pulmonary hypertension, and vascular remodeling.

Fig. 3.

Effect of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 on hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ protein in mouse lung. Adult wild-type (A) and dominant-negative mutant of TGF-β receptor type II (DnTGFβRII) mice (B) were exposed to hypoxia (10% O2, 1 atm) for 2 wk. PPAR-γ protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis and normalized with α-tubulin as an internal standard. n = number of mice. C: effects of 2-wk hypoxic exposure on muscularization of pulmonary arteries (50–100 μm in external diameter) in DnTGFβRII and wild-type mice. n = number of vessels from 5–6 mice per group. Results are means ± SE; *P < 0.05 compared with respective wild-type groups; #P < 0.05 compared with respective air control groups.

Table 1.

Effects of 2-wk hypoxic exposure (10% O2, 1 atm) on body weight, left ventricular and septal weight, and right ventricular weight of wild-type and DnTGFβRII mice

| Strain | Treatment (n) | BW, g | (LV+S)/BW, mg/g | RV/BW, mg/g | RV/(LV+S) | Hct, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Air (9) | 25.3 ± 1.0 | 3.24 ± 0.06 | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 45 ± 1 |

| Wild-type | Hypoxia (9) | 20.1 ± 1.0* | 3.77 ± 0.21* | 1.42 ± 0.06* | 0.38 ± 0.02* | 66 ± 1* |

| DnTGFβRII | Air (6) | 23.3 ± 0.7 | 3.73 ± 0.09# | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 47 ± 1 |

| DnTGFβRII | Hypoxia (5) | 23.2 ± 0.6# | 3.72 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.03† | 0.26 ± 0.01† | 60 ± 1*† |

Results are means ± SE, n = number of mice.

P < 0.05 vs. respective air control groups;

P < 0.05 vs. respective wild-type groups. DnTGFβRII, dominant-negative transforming growth factor-β receptor type II; BW, body weight; LV + S, left ventricular and septal weight; RV, right ventricular weight; Hct, hematocrit.

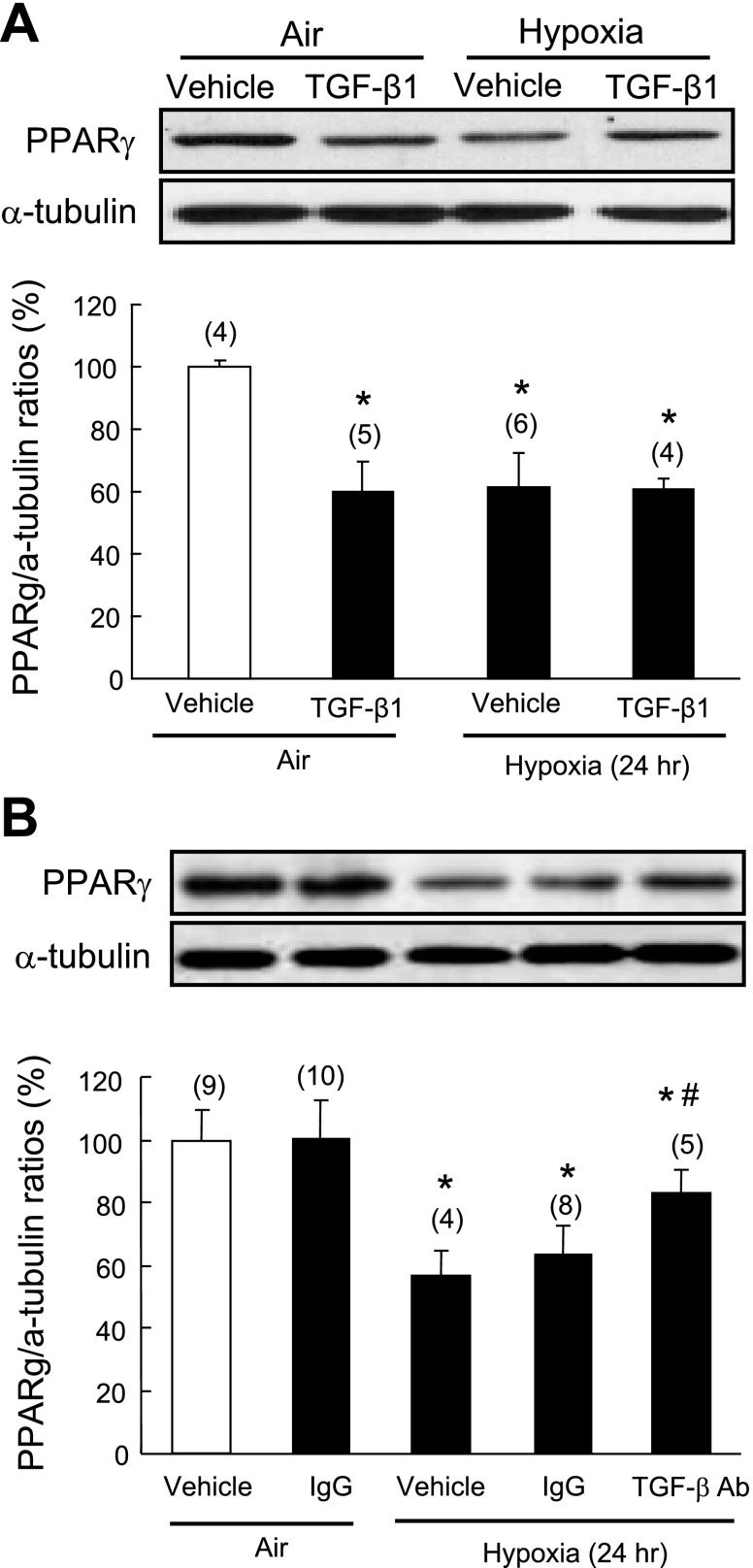

TGF-β is required for hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ in isolated PASMCs.

Because TGF-β1 signaling plays an important role in rodent models of pulmonary hypertension and PASMCs are known to be important targets of TGF-β signaling, we used isolated rat PASMCs to test the hypothesis that activation of TGF-β signaling mediates hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ in this critical cell type. Consistent with the results of the in vivo study, hypoxic exposure led to significant downregulation of PPAR-γ protein expression compared with air controls. Furthermore, TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) treatment also suppressed PPAR-γ protein in air controls but did not enhance the inhibitory effect of hypoxia on PPAR-γ expression (Fig. 4A). Pretreatment with a neutralizing antibody against TGF-β (50 μg/ml) effectively attenuated hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ in PASMCs, whereas control IgG had no effect on basal PPAR-γ expression (Fig. 4B), confirming the functional role of TGF-β in mediating the hypoxia effect.

Fig. 4.

Effect of TGF-β1 on hypoxia-induced PPAR-γ downregulation in isolated pulmonary artery small muscle cells (PASMCs). A: quiescent rat PASMCs were pretreated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 1 h and then exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) for an additional 24 h. B: quiescent rat PASMCs were pretreated with TGF-β neutralizing antibody (50 μg/ml) or normal IgG for 1 h before normoxic (air) or hypoxic exposure for 24 h. Cellular PPAR-γ expression was determined by Western blot analysis and normalized using α-tubulin. Results are means ± SE; n = number of wells. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle in air control group; #P < 0.05 compared with vehicle in hypoxia group.

We have also demonstrated that TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) treatment suppressed PPAR-γ protein expression in isolated rat aortic SMCs (Supplemental Fig. S1; supplemental material for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology website), indicating that the downregulation of PPAR-γ in response to TGF-β1 is not unique to PASMCs.

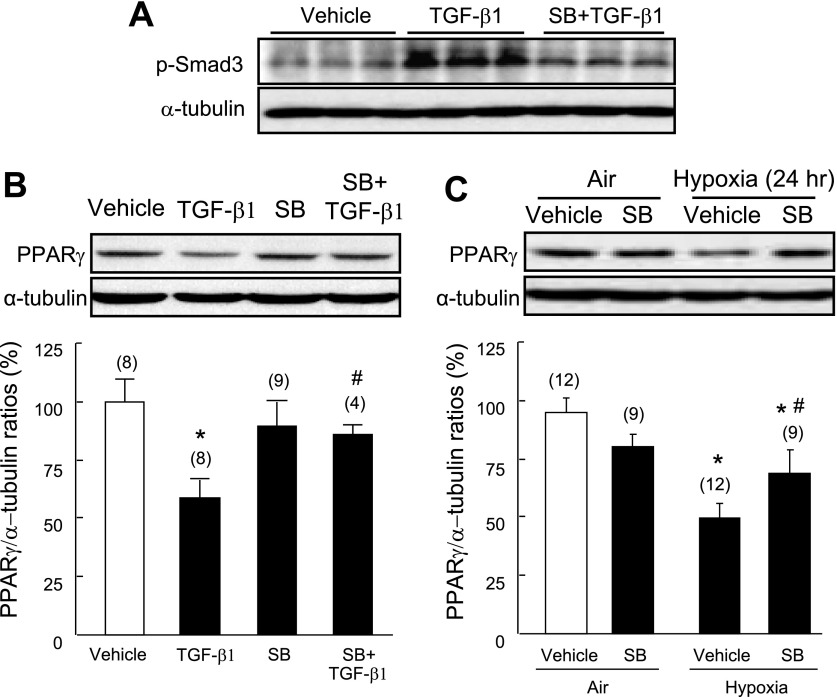

TGF-β suppresses PPAR-γ expression in PASMCs via a TGFβRI kinase-dependent pathway.

The intrinsic kinase activity of TGF-β receptor type I (TGFβRI) has an essential role in initiating the classic TGF-β/Smad pathway (8). However, Sorrentino et al. (28) recently demonstrated that the kinase activity of TGFβRI is not required for TGF-β to induce apoptosis via a Smad-independent, TRAF6-TAK1-p38/JNK pathway. To test whether TGFβRI kinase activity is required for TGF-β-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ, isolated PASMCs were pretreated with the selective TGFβRI kinase (activin receptor-like kinase 5, ALK5) inhibitor SB431542 (0.5 μM) for 1 h, and then exposed to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 30 min or 24 h. We observed that inhibition of TGFβRI kinase activation significantly inhibited TGF-β-induced Smad3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5A) and fully abolished TGF-β1-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ protein expression (Fig. 5B), suggesting that TGF-β induces downregulation of PPAR-γ expression in a receptor kinase-dependent manner. Consistent with the results of the study using TGF-β-neutralizing antibody, pretreatment with SB43542 significantly attenuated hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ protein expression in isolated PASMCs (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Effect of a TGFβRI antagonist on TGF-β1- and hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ. Quiescent rat PASMCs were pretreated with the ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 (SB, 0.5 μM) for 1 h, then challenged with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 30 min (A) or 24 h (B). Smad3 phosphorylation (30 min after TGF-β1 treatment) (A) and PPAR-γ protein expression (24 h after TGF-β1 treatment) (B) were detected by Western blot analysis and normalized using α-tubulin as an internal control. C: PASMCs were pretreated with SB431542 (0.5 μM) for 1 h, then exposed to hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 h. Western blot of PPAR-γ protein was normalized using α-tubulin. Results are means ± SE; n = number of wells. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control; #P < 0.05 compared with TGF-β1 alone or hypoxia.

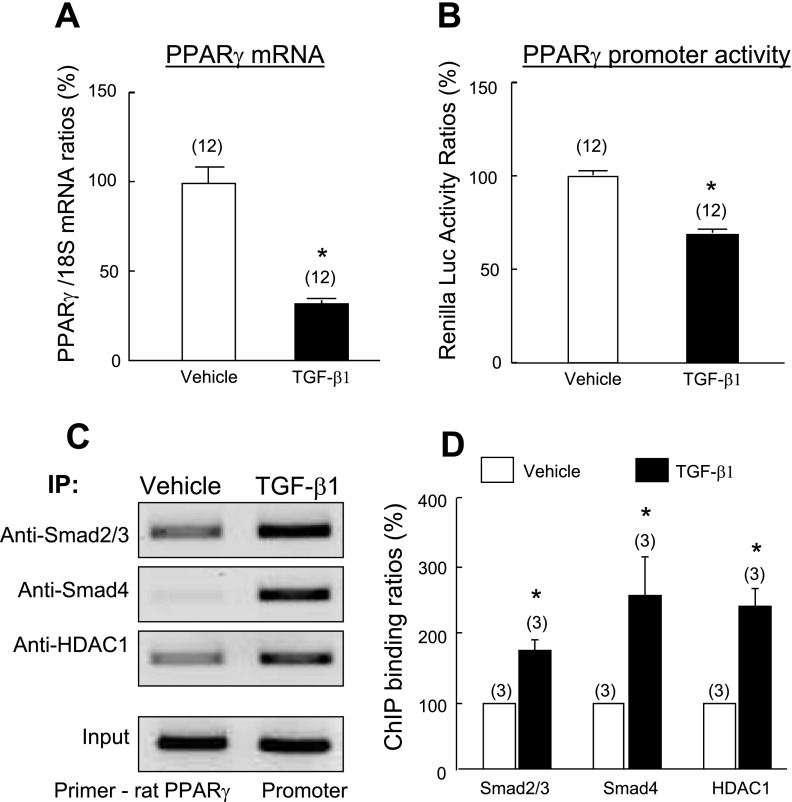

TGF-β suppresses PPAR-γ expression in PASMCs at the transcription level.

To test the hypothesis that TGF-β1-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ expression in PASMCs occurs at the transcriptional level, quiescent PASMCs were exposed to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 24 h, and steady-state PPAR-γ mRNA was measured using real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Consistent with its effect on protein expression, TGF-β1 treatment significantly decreased PPAR-γ mRNA expression (Fig. 6A). To determine the effect of TGF-β1 on the transcriptional activity of the PPAR-γ gene, PASMCs were transfected with a plasmid containing a human PPAR-γ promoter and incubated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for 24 h. Measurement of luciferase activities demonstrated that TGF-β1 treatment decreased PPAR-γ promoter activity significantly (by 31%) (Fig. 6B). Together, these results provide evidence that TGF-β inhibits PPAR-γ gene expression in PASMCs at the transcriptional level.

Fig. 6.

Effects of TGF-β1 on PPAR-γ mRNA and transcriptional activity. A: quiescent rat PASMCs were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) or vehicle for 24 h. The PPAR-γ mRNA level was determined by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized using 18S rRNA levels as an internal control. B: rat PASMCs were cotransfected with pGL3-hPPAR-γ promoter-Luc and pRL-TK plasmid and then exposed to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) or vehicle for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured by luminescence. C and D: chromatin immunoprecipitation (IP) analyses for detection of Smad2/3, Smad4 and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) at the PPAR-γ promoter. Quiescent PASMCs were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) or vehicle for 1 h. The Smad2/3, Smad4, and HDAC1 binding levels at the PPAR-γ promoter were determined by specifically amplified PPAR-γ promoter fragment with PCR. A representative set of results from 3 independent assays is shown. Results are means ± SE. n = number of wells. *P < 0.05 compared with respective vehicle controls.

TGF-β1 treatment increases binding of Smad2/3/4 and HDAC1 proteins to the PPAR-γ promoter in PASMCs.

Our demonstration that TGF-β-mediated PPAR-γ suppression depends on TGFβRI kinase activity suggests involvement of Smad2/3 in this process. To test directly whether activation of TGF-β1 signaling suppresses PPAR-γ gene expression by modulating binding of Smads to the PPAR-γ promoter, we used the ChIP technique. Quiescent rat PASMCs were treated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) or vehicle for 1 h, and nuclear protein-DNA complexes were extracted and subjected to ChIP analysis with selective anti-Smad2/3 and anti-Smad4 antibodies. In the absence of TGF-β1, moderate levels of Smad2 and/or Smad3 and Smad4 were evident at the PPAR-γ promoter, and activation of TGF-β signaling enhanced levels of Smad2 and/or Smad3 and Smad4 at the promoter region of the PPAR-γ gene (Fig. 6C). To further define the mechanism of TGF-β/Smad activation-induced inhibition of PPAR-γ transcription, protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated using antibody against HDAC1, a transcriptional corepressor that inhibits transcription by decreasing histone acetylation (23). ChIP assay determined that, in the absence of TGF-β1, a low level of HDAC1 was present at the PPAR-γ promoter, whereas TGF-β1 treatment significantly increased the binding of HDAC1 at the PPAR-γ promoter (Fig. 6D), providing evidence that the PPAR-γ gene is transcriptionally inactive in the presence of TGF-β1.

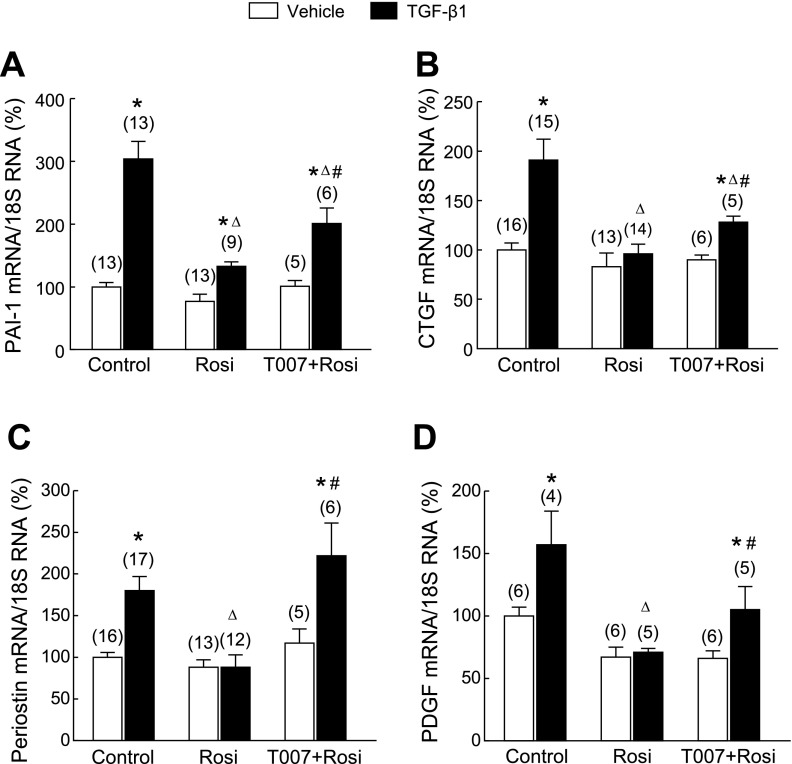

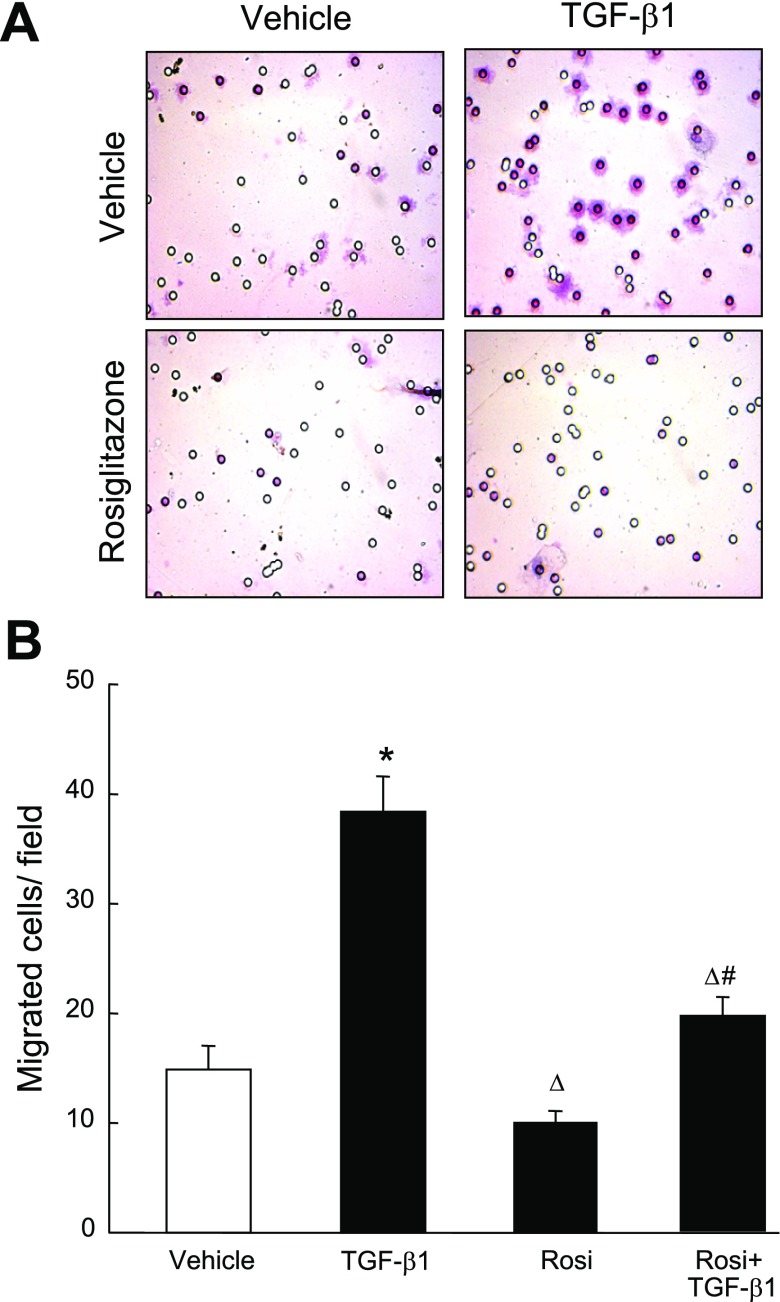

Pharmacological activation of PPAR-γ inhibits TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix molecule expression and PASMC migration.

To assess directly the functional antagonism of PPAR-γ on the downstream effects on TGF-β/Smad3 signaling, we tested whether PPAR-γ agonist treatment antagonizes the stimulatory effects of TGF-β1 on PAI-1, CTGF, periostin, and PDGF expression in PASMCs, as well as PASMC migration. Cells were pretreated with the PPAR-γ agonist Rosi (0.1 μM) for 24 h and incubated with TGF-β1 for 12 h. TGF-β1 treatment significantly increased expression of PAI-1, CTGF, periostin, and PDGF mRNA (Fig. 7), and PASMC migration (Fig. 8). Rosi pretreatment significantly attenuated the stimulatory effect of TGF-β1 on expression of these molecules. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of Rosi were partially inhibited by pretreatment with the highly selective PPAR-γ antagonist T007090 (T007, 0.5 μM, 1 h before Rosi) (16). These data provide evidence that PPAR-γ antagonizes the stimulatory effects of enhanced TGF-β signaling in PASMCs under chronic hypoxic stress.

Fig. 7.

Effects of pretreatment with the PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone (Rosi) on TGF-β1-induced expression of extracellular matrix molecules in PASMCs. Quiescent PASMCs were pretreated with Rosi (0.1 μM) or vehicle for 24 h and then stimulated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 12 h. The relative mRNA levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) (A), connect tissue growth factor (CTGF) (B), periostin (C), and PDGF (D) were determined by real-time PCR. Results are means ± SE; n = number of wells. *P < 0.05 compared with respective vehicle groups; ΔP < 0.05 compared with respective TGF-β1 alone groups; #P < 0.05 compared with respective Rosi + TGF-β1 group.

Fig. 8.

Effect of Rosi pretreatment on TGF-β1-induced migration of PASMCs. Quiescent PASMCs (0.5 × 105) were seeded in Falcon cell culture inserts (8.0-μm pore size), pretreated with Rosi (0.1 μM) or vehicle for 3 h, then stimulated with TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 12 h. The cells adherent to the outer surface of the lower side of the membrane were counted. A: micrographs (×400) of the hematoxylin-stained cells that migrated through the pores. B: bar graphs summarize the number of PASMCs adherent to the lower side of the chamber. Results are means ± SE, n = 15 wells/group. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle group; ΔP < 0.05 compared with TGF-β1 alone group; #P < 0.05 compared with respective Rosi alone group.

DISCUSSION

The current study provides the first demonstration that hypoxia inhibits PPAR-γ protein expression in rat lung and isolated PASMCs via a TGF-β-dependent mechanism. We further demonstrated that TGF-β inhibits PPAR-γ downregulation at the transcriptional level through increasing Smad2/3/4 and HDAC1 binding at the promoter of PPAR-γ in isolated PASMCs. With the use of these isolated PASMC as an in vitro model, these provocative findings define a novel molecular mechanism for counterregulatory effects of TGF-β and PPAR-γ signaling in mediating pulmonary vascular responses to hypoxic stress.

PPAR-γ plays a modulatory role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling via multiple mechanisms (32). In vivo studies have shown that transgenic mouse models with either SMC- or endothelial cell-specific deletion of PPAR-γ develop mild pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling under normoxic conditions (9, 11). Furthermore, administration of PPAR-γ agonists both prevents and reverses hypoxia- and monocrotaline-induced right ventricular hypertrophy and pulmonary artery neomuscularization in normal mice and rats, as well as in apoE knockout mice fed a high-fat diet (6, 12, 24). In this study, we have shown that hypoxic exposure downregulated PPAR-γ expression in medial (250 μm in diameter) and large (750 μm) pulmonary arteries. In small pulmonary arteries (<200 μm), the PPAR-γ was too low to be detected because of thin SMC media or partially muscularized vessels (data not shown). These results support the finding of Crossno et al. (6) that PPAR-γ may be effective in attenuating the (larger) pulmonary arterial remodeling but not the elevated pulmonary arterial pressure (pulmonary hypertension).

In additional experiments, we have observed that TGF-β1 treatment also suppressed PPAR-γ protein expression in isolated rat aortic SMCs (Supplemental Fig. S1), indicating that the downregulation of PPAR-γ in response to TGF-β1 is not unique to PASMCs. These results suggest that, in addition to hypoxic stress, the interactions between TGF-β/Smad and PPAR-γ signaling may also play an important role in the remodeling of systemic vasculature under stressful conditions (e.g., vascular endoluminal injury that activates TGF-β1 expression).

In vitro studies have demonstrated that reduced expression of PPAR-γ is associated with increased proliferation and extracellular matrix molecule expression by SMCs. For example, it has been shown that PPAR-γ protein expression in aortic SMCs from spontaneously hypertensive rats, a strain characterized by enhanced proliferation of arterial SMCs, is significantly lower than in nomotensive control Wistar-Kyoto rats, which have lower SMC proliferation rates. Adenovirus-mediated PPAR-γ overexpression significantly inhibited the exaggerated proliferation of aortic SMCs from spontaneously hypertensive rats (31). Clinically, PPAR-γ expression is reduced in pulmonary artery of patients with severe PH (2). Collectively, these findings suggest that reduced PPAR-γ expression plays a mechanistic role in chronic hypoxia-induced PH and pulmonary arterial remodeling.

More recently, Kim et al. (15) showed that PPAR-γ expression is downregulated in rat lung under chronic hypoxia stress (15). We also observed that chronic hypoxia led to downregulation of PPAR-γ protein expression in both rat and mouse lung, especially in hypertrophied pulmonary arteries. Importantly, we demonstrated that disruption of TGF-β signaling in DnTGFβRII mice attenuated chronic hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ expression. Furthermore, our in vitro studies showed that blocking TGF-β signaling with either a TGF-β neutralizing antibody or a TGFRI inhibitor significantly attenuated hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ in isolated PASMCs. These results indicate that, under chronic hypoxia conditions, TGF-β activation mediates downregulation of PPAR-γ expression in lung.

TGF-β, via its receptors TGFβRI and TGFβRII, triggers cytoplasmic Smad2/3 activation that depends on the phosphorylation of TGFβRI induced by constitutively active TGFβRII in the receptor complex. TGFβRI has recently been shown to interact directly with ubiquitin ligase (E3) TRAF6 and induce Lys 63-linked polyubiquitylation of TAK1, thus activating the TAK1-p38/JNK pathway in a receptor kinase- and Smad-independent manner (28). Although vascular SMCs express multiple isoforms of TGFβRI, i.e., ALK1–7, most of the effects of TGF-β on SMC function appear to be mediated via the ALK5 (4). To determine whether TGF-β-induced inhibition of PPAR-γ expression requires intrinsic kinase activation of TGFβRI, we pretreated isolated PASMCs with the selective ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 before TGF-β administration. Our results clearly demonstrated that inhibition of TGFβRI kinase activation effectively abolished TGF-β-induced Smad3 phosphorylation and significantly attenuated downregulation of PPAR-γ. These findings suggest that TGF-β-induced Smad3 activation by TGFβRI plays an important role in hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ expression. Our observations are consistent with the previous demonstration that inhibition of ALK5 activation with the selective antagonist SB525334 attenuated TGF-β-induced proliferation-related gene expression and cellular proliferation of PASMCs from patients with idiopathic PH in vitro and significantly decreased pulmonary arterial pressure and inhibited right ventricular hypertrophy in monocrotaline-treated rats in vivo (29).

Our observation that TGF-β signaling suppresses PPAR-γ expression at the transcriptional level in PASMCs is consistent with previous studies. Fu et al. (7) have reported that exposure to TGF-β1 for periods >12 h suppressed PPAR-γ mRNA expression in human aortic SMCs (7). Conversely, in activated rat hepatic stellate cells, interruption of TGF-β signaling by curcumin has been shown to upregulate PPAR-γ gene expression (33). TGF-β-mediated transcriptional modulation requires Smad protein binding to the promoters of target genes. Our ChIP indicated that the PPAR-γ promoter is constitutively bound by Smad2/3 and Smad4 proteins and that binding of Smad2/3/4 proteins to the PPAR-γ promoter increases in response to TGF-β1 treatment, suggesting a role for Smad protein in this process. Future studies will be needed to map the precise regions of Smad binding at the PPAR-γ promoter that mediate inhibition of PPAR-γ gene expression by TGF-β1. The observation that TGF-β1-stimulated binding of Smad2/3/4 enhances the recruitment of HDAC1 at the PPAR-γ promoter provides additional evidence that TGF-β1 downregulates PPAR-γ gene expression through a transcriptional mechanism.

PPAR-γ agonists have been shown to suppress proliferation of PASMCs by stabilizing the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1 and to induce apoptosis of proliferating SMCs by blocking the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase survival pathway (13). The current study added to that body of knowledge by demonstrating that the PPAR-γ agonist Rosi inhibits TGF-β-induced stimulation of extracellular matrix molecule expression by PASMCs, thus suggesting that the modulatory effect of these agents on PH and pulmonary vascular remodeling may be related to attenuation of TGF-β signaling.

In summary, this study provides the first evidence that TGF-β/Smad signaling plays a critical role in hypoxia-induced downregulation of PPAR-γ in lung. In isolated PASMCs, we also demonstrated that activation of TGF-β signaling suppresses PPAR-γ expression via a transcriptional regulatory mechanism. These findings provide important information of the mechanism(s) of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling.

GRANTS

This work was supported, in part, by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants: HL080017, HL044195 (Y.-F. Chen), HL07457, HL75211, HL087980 (S. Oparil), HL092906 (N. Ambalavanan), and by American Heart Association Grants 10POST3180007 (K. Gong) and 09BGIA2250367 (D. Xing).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.G., D.X., N.A., Q.Y., S.E.N., S.O., and Y.-F.C. conception and design of research; K.G., D.X., P.L., and B.A. performed experiments; K.G., D.X., and Y.-F.C. analyzed data; K.G., D.X., N.A., Q.Y., S.E.N., S.O., and Y.-F.C. interpreted results of experiments; K.G. and Y.-F.C. prepared figures; K.G. and Y.-F.C. drafted manuscript; S.O. and Y.-F.C. edited and revised manuscript; S.O. and Y.-F.C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ambalavanan N, Nicola T, Hagood J, Bulger A, Serra R, Murphy-Ullrich J, Oparil S, Chen YF. Transforming growth factor-β signaling mediates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling and inhibition of alveolar development in newborn mouse lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L86–L95, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ameshima S, Golpon H, Cool CD, Chan D, Vandivier RW, Gardai SJ, Wick M, Nemenoff RA, Geraci MW, Voelkel NF. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) expression is decreased in pulmonary hypertension and affects endothelial cell growth. Circ Res 92: 1162–1169, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Archer SL, Weir EK, Wilkins MR. Basic science of pulmonary arterial hypertension for clinicians: new concepts and experimental therapies. Circulation 121: 2045–2066, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bobik A. Transforming growth factor-betas and vascular disorders. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 1712–1720, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen YF, Feng JA, Li P, Xing D, Zhang Y, Serra R, Ambalavanan N, Majid-Hassan E, Oparil S. Dominant negative mutation of the TGF-β receptor blocks hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Appl Physiol 100: 564–571, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crossno JT, Jr, Garat CV, Reusch JEB, Morris KG, Dempsey EC, McMurtry IF, Stenmark KR, Klemm DJ. Rosiglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L885–L897, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fu M, Zhang J, Lin Y, Zhu X, Zhao L, Ahmad M, Ehrengruber MU, Chen YE. Early stimulation and late inhibition of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) gene expression by transforming growth factor beta in human aortic smooth muscle cells: role of early growth-response factor-1 (Egr-1), activator protein 1 (AP1) and Smads. Biochem J 370: 1019–1025, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gough NR. Kinase-independent signaling from TGF-beta receptors to TAK1. Sci Signal 1: ec348, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guignabert C, Alvira CM, Alastalo TP, Sawada H, Hansmann G, Zhao M, Wang L, El-Bizri N, Rabinovitch M. Tie2-mediated loss of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in mice causes PDGF receptor-β-dependent pulmonary arterial muscularization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1082–L1090, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hamblin M, Chang L, Fan Y, Zhang J, Chen YE. PPARs and the cardiovascular system. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 1415–1452, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hansmann G, de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo TP, Alvira CM, Guignabert C, Bekker JM, Schellong S, Urashima T, Wang L, Morrell NW, Rabinovitch M. An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARgamma/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest 118: 1846–1857, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hansmann G, Wagner RA, Schellong S, de Jesus Perez VA, Urashima T, Wang L, Sheikh AY, Suen RS, Stewart DJ, Rabinovitch M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is linked to insulin resistance and reversed by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation. Circulation 115: 1275–1284, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hansmann G, Zamanian RT. PPARgamma activation: a potential treatment for pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med 1: 12ps14, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jeffery TK, Morrell NW. Molecular and cellular basis of pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 45: 173–202, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim EK, Lee JH, Oh YM, Lee YS, Lee SD. Rosiglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats. Respirology 15: 659–668, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee G, Elwood F, McNally J, Weiszmann J, Lindstrom M, Amaral K, Nakamura M, Miao S, Cao P, Learned RM, Chen JL, Li Y. T0070907, a selective ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, functions as an antagonist of biochemical and cellular activities. J Biol Chem 277: 19649–19657, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li P, Oparil S, Feng W, Chen YF. Hypoxia-responsive growth factors upregulate periostin and osteopontin expression via distinct signaling pathways in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Appl Physiol 97: 1550–1558, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li P, Oparil S, Novak L, Cao X, Shi W, Lucas J, Chen YF. ANP signaling inhibits TGF-β-induced Smad2 and Smad3 nuclear translocation and extracellular matrix expression in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Appl Physiol 102: 390–398, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li P, Wang D, Lucas J, Oparil S, Xing D, Cao X, Novak L, Renfrow MB, Chen YF. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits transforming growth factor-beta-induced smad signaling and myofibroblast transformation in mouse cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Res 102: 185–192, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Long L, Crosby A, Yang X, Southwood M, Upton PD, Kim DK, Morrell NW. Altered bone morphogenetic protein and transforming growth factor-beta signaling in rat models of pulmonary hypertension: potential for activin receptor-like kinase-5 inhibition in prevention and progression of disease. Circulation 119: 566–576, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lucas JA, Zhang Y, Li P, Gong K, Miller AP, Hassan E, Hage F, Xing D, Wells B, Oparil S, Chen YF. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-β signaling induces left ventricular dilation and dysfunction in the pressure-overloaded heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H424–H432, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Milam JE, Keshamouni VG, Phan SH, Hu B, Gangireddy SR, Hogaboam CM, Standiford TJ, Thannickal VJ, Reddy RC. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit profibrotic phenotypes in human lung fibroblasts and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L891–L901, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moustakas A, Souchelnytskyi S, Heldin CH. Smad regulation in TGF-beta signal transduction. J Cell Sci 114: 4359–4369, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nisbet RE, Bland JM, Kleinhenz DJ, Mitchell PO, Walp ER, Sutliff RL, Hart CM. Rosiglitazone attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 42: 482–490, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nozell S, Laver T, Moseley D, Nowoslawski L, DeVos M, Atkinson GP, Harrison K, Nabors LB, Benveniste EN. The ING4 tumor suppressor attenuates NF-kappaB activity at the promoters of target genes. Mol Cell Biol 28: 6632–6645, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rabinovitch M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Clin Invest 118: 2372–2379, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Selimovic N, Bergh CH, Andersson B, Sakiniene E, Carlsten H, Rundqvist B. Growth factors and interleukin-6 across the lung circulation in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 34: 662–668, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sorrentino A, Thakur N, Grimsby S, Marcusson A, von Bulow V, Schuster N, Zhang S, Heldin CH, Landstrom M. The type I TGF-beta receptor engages TRAF6 to activate TAK1 in a receptor kinase-independent manner. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1199–1207, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas M, Docx C, Holmes AM, Beach S, Duggan N, England K, Leblanc C, Lebret C, Schindler F, Raza F, Walker C, Crosby A, Davies RJ, Morrell NW, Budd DC. Activin-like kinase 5 (ALK5) mediates abnormal proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells from patients with familial pulmonary arterial hypertension and is involved in the progression of experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension induced by monocrotaline. Am J Pathol 174: 380–389, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tuder RM, Abman SH, Braun T, Capron F, Stevens T, Thistlethwaite PA, Haworth SG. Development and pathology of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: S3–S9, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xiong C, Mou Y, Zhang J, Fu M, Chen YE, Akinbami MA, Cui T. Impaired expression of PPARgamma protein contributes to the exaggerated growth of vascular smooth muscle cells in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Life Sci 77: 3037–3048, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yuan JXJ, Ward JPT, Rabinovitch M. PPARγ and the pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. In: Membrane Receptors, Channels and Transporters in Pulmonary Circulation. New York, NY: Humana, 2010, p.447–458. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zheng S, Chen A. Disruption of transforming growth factor-β signaling by curcumin induces gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in rat hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G113–G123, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]