Abstract

Background: identification of individuals with high fracture risk from within primary care is complex. It is likely that the true contribution of falls to fracture risk is underestimated.

Methods: cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort of 3,200 post-menopausal women aged 73 ± 4 years. Self-reported data were collected on fracture, osteoporosis clinical risk factors and falls/mobility risk factors. Self-reported falls were compared with recorded falls on GP computerised records. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify independent risk factors for fracture.

Results: a total of 838 (26.2%) reported a fracture after aged 50; 441 reported falling more than once per year, but 69% of these had no mention of falls on their computerised GP records. Only age [odds ratios (OR): 1.37 per 5 year increase, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.23–1.53], height (1.02 per cm increase, 95% CI: 1.01–1.04), weight (OR: 0.99 per kg increase, 95% CI: 0.98–0.99) and falls (OR: 1.49 for more than once per year compared with less, 95% CI: 1.13–1.94) were independent risk factors for fracture. Falls had the strongest association.

Conclusion: when identifying individuals with high fracture risk we estimate that more than one fall per year is at least twice as important as height and weight. Furthermore, using self-reported falls data is essential as computerised GP records underestimate falls prevalence.

Keywords: fractures, falls, COSHIBA, FRAX, cohort study, elderly

Introduction

Osteoporosis is one of the commonest diseases to affect the elderly, and by the year 2050 the number of men and women estimated to be affected will be more than 30 million in the EU [1]. The consequences of osteoporosis are bone fractures resulting in morbidity, reduced quality of life and mortality. If an individual is identified as being at high risk of osteoporotic fracture, bone-protective medication is available such as bisphosphonates, which reduce the risk of future fracture by approximately 50% [2].

However, assessing an individual's fracture risk is complex. Despite the established inverse relationship between bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture, approximately half of hip fractures occur in women whose BMD is above the osteoporotic threshold [3]. A range of clinical risk factors are also informative, as used by the WHO fracture prediction tool FRAX [4]. FRAX provides an estimate of risk of hip and other osteoporotic fractures over the following 10 years. The clinical risk factors it incorporates were chosen from the results of meta-analyses [5, 6] and include age, body mass index (BMI) [7], glucocorticoids [8], previous fractures [9], family history of hip fracture [10], smoking [11], alcohol intake [12] and secondary causes of osteoporosis.

One limitation of FRAX is that it does not include falls or mobility which are noteworthy determinants of fracture risk [13]. There is increasing evidence for the efficacy of multidisciplinary interventions in reducing fracture risk by a reduction in falls [14]. An analysis of a Swedish community-based intervention aimed at preventing falls suggests it may be as cost-effective as bone-protective therapy in the prevention of hip fractures [15]. At least two previous studies have found that a history of falls predict fractures independently of other risk factors such as those included in FRAX, and that integration of this information may enable more accurate prediction of fractures [16, 17]. Since both studies used data from computerised General Practice records [The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database and QResearch database] rather than self-reported data, the true rate of variables such as falls may have been underestimated.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the relative strength of associations between conventional risk factors for osteoporosis or risk factors related to falls and mobility and overall fracture risk, based on self-reported data as opposed to computerised GP records.

Methods

Study design

Cross-sectional analysis of a large population-based cohort study of post-menopausal women.

Study population

The Cohort for Skeletal Health in Bristol and Avon (COSHIBA) is a population-based cohort of 3,200 women with a date of birth between 1 January 1927 and 31 December 1942 from South-West England. Women were invited to take part with the only entry criterion a date of birth within the required range. For further details about recruitment and representative nature see Supplementary data Appendix 1 in Age and Ageing online. Data were collected from the participants on entry to the study by self-completion questionnaires after obtaining written consent. For details of questionnaire please see Supplementary Data Appendix 2 in Age and Ageing online. Ethical approval was obtained from the Gloucestershire Research Ethics Committee (REC 07/Q2005/47).

Outcome measure: reported fractures

Data were collected on self-reported fractures since aged 50 years. A random 5% subsample of reported fractures were verified against GP records: 79.5% of reported fractures were confirmed, similar to that found by other researchers [18]. Data were also collected on the mechanism of injury, allowing classification by the researchers based on description of the injury into slight/low or other trauma, based on the modified-Landin descriptions [19].

Exposure measures: clinical risk factors

Self-reported data were collected on various clinical risk factors for fracture. To validate this self-reported data a random 5% subsample (n = 150) of COSHIBA participants had their self-completed baseline questionnaires compared with their electronic GP records. For further details see Supplementary Data Appendix 3 in Age and Ageing online.

Age: calculated from date of birth.

Height and weight: self-reported.

Parental hip fracture: self-reported history of maternal hip fracture.

Current smoking: self-reported smoking, where non- and ex-smokers were grouped together.

Use of glucocorticoids: self-reported use of oral steroids for more than 3 months as an adult.

Secondary causes of osteoporosis: self-reported history of secondary causes of osteoporosis over the previous 2 years: Cushings disease, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, polymyalgia rheumatica and multiple sclerosis. Self-report of rheumatoid arthritis and hyperthyroidism was not used because of poor validity.

Alcohol intake of 3 or more units per day: self-reported alcohol intake of at least one drink per day.

Previous fracture: self-reported fractures occurring during adult life (aged 18–50), arising from slight trauma as used in FRAX.

Exposure measures: falls/mobility

Fall frequency: participants were asked about the number of falls they had experienced over the last 5 years. Falls were divided into a binary variable of a fall frequency of more than once a year compared with less.

Mobility: self-reported furthest walking distance of less than 400 yards was classified as a risk factor.

Use of a walking aid: self-reported use of any walking aid either sometimes or regularly was classed as a risk factor.

Data management and statistical analysis

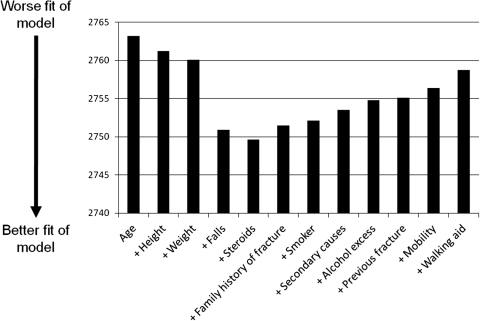

The outcome measure was reported fractures since aged 50. With our sample size and assuming an α-level error of 5% we have greater than 80% power to identify a 5% difference between those with and without fracture after 50. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to describe the association between risk factors and presence or absence of reported fracture since aged 50. To look for independent associations with fracture risk, all variables were included in the final multivariable logistic regression analysis. To assess the additional predictive ability of including falls with clinical risk factors, the pseudo R 2 and Chi-squared values were visually compared—larger values indicate better predictive ability, and the likelihood ratio test (LRT) was used to assess if the difference seen could have occurred by chance. Furthermore, a Fit Statistic (AIC, Akaike's Information Criterion) was calculated for the logistic regression model, introducing the clinical risk factors in a stepwise fashion. AIC indicates the goodness of fit of the model with lower values indicating better fit. A Scree Plot was then drawn to show the change in AIC with each additional risk factor in an attempt to quantify the additional benefit of falls/mobility clinical risk factors. Risk factors were added in differing orders based on investigator choice to check for robustness of the change in AIC on adding falls to the model predicting fractures. Participants with missing data were excluded from relevant analyses.

Results

Of a total of 8,224 eligible women, 7,080 were invited from 15 general practices, and 3,200 (45.2%) enrolled. Similar to all studies where a representative sample has been attempted, COSHIBA has a shortfall in less affluent participants (see Supplementary data Appendix 1 in Age and Ageing online). The mean age of the cohort was 72.7 ± 4.3 years (95% range from 66.6 to 79.9 years), and 838 (26.2%) reported a fracture after aged 50. Of these, 420 (50.1%) reported an upper limb fracture, 262 (31.3%) lower limb and 80 (9.6%) reported both. Out of the entire cohort, 441 (14.4%) of women reported falling a few times a year or more (i.e. more than once per year). A random 5% subsample were verified against GP records and 69.2% of those reporting falling more than once per year had no falls recorded on the computerised GP records, suggesting that these electronic records underestimate the true prevalence of falls.

Those with reported fracture after aged 50 were older (73.5 ± 4.4 years versus 72.4 ± 4.2), had more falls (18.1% fell more than once per year versus 13.0%) and were more likely to use a walking aid (24.6% versus 19.8%) compared with those without fracture. No other clinical or falls/mobility risk factors differed between the two groups (Table 1), although there was a suggestion that women with reduced mobility were more likely to have a fracture (P = 0.056).

Table 1.

Clinical risk factors and falls/mobility risk factors in those with and without reported fracture after aged 50

| Total number with complete data |

With fracture after aged 50 mean (SD) | No fracture mean (SD) | P-value for difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With fracture | No fracture | ||||

| n | n | ||||

| Clinical risk factors | |||||

| Age | 838 | 2,361 | 73.5 (4.4) | 72.4 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 740 | 2,115 | 160.3 (6.8) | 160.1 (6.4) | 0.513 |

| Weight (kg) | 796 | 2,245 | 69.2 (13.4) | 69.5 (13.2) | 0.520 |

| n | n | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Maternal hip fracture | |||||

| No | 826 | 2,324 | 669 (81.0) | 1,831 (78.8) | 0.205 |

| Yes | 79 (9.6) | 275 (11.8) | |||

| Unknown | 78 (9.4) | 218 (9.4) | |||

| Current smoking | |||||

| No | 827 | 2,327 | 763 (92.3) | 2,149 (92.4) | 0.934 |

| Yes | 64 (7.7) | 178 (7.7) | |||

| Steroids >3 months | |||||

| No | 784 | 2,241 | 714 (91.1) | 2,060 (91.9) | 0.457 |

| Yes | 70 (8.9) | 181 (8.0) | |||

| Secondary causesa | |||||

| No | 836 | 2,348 | 782 (93.5) | 2,193 (93.4) | 0.887 |

| Yes | 54 (6.5) | 155 (6.6) | |||

| Excess alcohol | |||||

| No | 827 | 2,333 | 727 (87.9) | 2,035 (87.2) | 0.612 |

| Yes | 100 (12.1) | 298 (12.8) | |||

| Previous fractures aged 18–50 | |||||

| No | 838 | 2,361 | 787 (93.9) | 2,250 (95.3) | 0.116 |

| Yes | 51 (6.1) | 111 (4.7) | |||

| Falls/mobility risk factors | |||||

| Fall frequency | |||||

| Less than once per year | 805 | 2,263 | 659 (81.9) | 1,968 (87.0) | <0.001 |

| More than once per year | 146 (18.1) | 295 (13.0) | |||

| Mobility | |||||

| Walking distance >400 yards | 816 | 2,274 | 608 (74.5) | 1,769 (77.8) | 0.056 |

| Walking distance <400 yards | 208 (25.5) | 505 (22.2) | |||

| Use of walking aid | |||||

| No | 831 | 2,315 | 627 (75.5) | 1,857 (80.2) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 204 (24.6) | 458 (19.8) | |||

aSecondary causes encompass self-reported Cushings disease, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, polymyalgia rheumatica and multiple sclerosis.

Using a model with just the clinical variables, only age (OR: 1.40 per 5-year increase, 95% CI: 1.26–1.57), height (OR: 1.02 per cm increase, 95% CI: 1.01–1.04) and use of steroids for more than 3 months (OR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.04–2.06) were independently associated with fractures. Similar analyses were carried out for the falls/mobility risk factors and only falls was an independent falls/mobility risk factor (OR: 1.47 for more than once per year, 95% CI: 1.13–1.91). Similar results were seen after limiting analyses to those with low trauma fractures, and after dropping rare falls (results not shown).

When combining all clinical and falls/mobility risk factors (Table 2) only age (OR: 1.37 per 5-year increase, 95% CI: 1.23–1.53), height (1.02 per cm increase, 95% CI: 1.01–1.04), weight (OR: 0.99 per kg, 95% CI: 0.98–0.99) and falls (OR 1.49 more than once per year, 95% CI: 1.13–1.94, P = 0.004) were independent risk factors. Replacing height and weight with BMI did not change the results.

Table 2.

Independent association between clinical and falls/mobility-related risk factors and fractures in this population of 2,424 elderly women

| Risk factor | OR for fracture risk adjusted for all other variables in the table, OR (95% CI) | P-value for independent association |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per 5 years) | 1.37 (1.23–1.53) | <0.001 |

| Height (per cm) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.005 |

| Weight (per kg) | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0.021 |

| Family history of hip fracture | 0.819 | |

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 0.91 (0.68–1.23) | |

| Unknown | 1.01 (0.71–1.43) | |

| Current smoking | ||

| No | 1.0 | 0.249 |

| Yes | 1.24 (0.86–1.78) | |

| Steroids for >3 months | ||

| No | 1.0 | 0.062 |

| Yes | 1.39 (0.99–1.98) | |

| Secondary causes of osteoporosis | ||

| No | 1.0 | 0.401 |

| Yes | 0.85 (0.57–1.25) | |

| Excess alcohol | ||

| No | 1.0 | 0.426 |

| Yes | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) | |

| Previous fractures | ||

| No | 1.0 | 0.202 |

| Yes | 1.30 (0.87–1.93) | |

| Fall frequency | ||

| Less than once per year | 1.0 | 0.003 |

| More than once per year | 1.49 (1.13–1.94) | |

| Mobility | ||

| Walking distance >400 yards | 1.0 | 0.652 |

| Walking distance <400 yards | 1.06 (0.81–1.40) | |

| Use of walking aid | ||

| No | 1.0 | 0.459 |

| Yes | 1.11 (0.84–1.47) | |

To assess which variables were most strongly associated with reported fracture after aged 50, we looked at the pseudo-R 2. In our model just containing the clinical risk factors this was 0.0189, whereas addition of the falls/mobility risk factors increased this to 0.0231 showing that more of the variance in fracture risk was explained by addition of falls. The LRT test indicated this improvement was unlikely to have occurred by chance (P < 0.001). To estimate quantification of the additional predictive ability of adding falls to the clinical risk factor model we looked at the AIC (Figure 1) which shows the biggest improvement in the model with the addition of falls, suggesting it is a stronger risk factor than age, height or weight. This was independent of the order in which the variables were introduced.

Figure 1.

A scree plot to show which clinical risk factors are the most important in determining fracture risk in this cohort. The plot shows change in goodness of fit with each additional clinical risk factor. Goodness of fit of the models is shown on the y-axis by AIC values where lower levels indicate better fit. The x-axis shows the clinical risk factors included in the models. The simplest model just contains age. All other clinical risk factors were added in a stepwise fashion such that the last model on the right-hand side contains all risk factors.

Discussion

Our results suggest that in the UK primary care-based population of older women, self-reported falls has the strongest association with self-reported fracture. Our Scree Plot suggests that reported falls explains the most variance in reported fractures, and it is at least twice as important as the other risk factors. As far as we are aware, this is the first report of the benefits, and quantification, of the addition of falls to the list of clinical risk factors using self-reported data, and suggests that previous analyses using computerised GP records have underestimated the importance of falls in fracture prediction.

The prospective cohort study of 366,104 women using the THIN database [16] reported age, previous fracture, falls, BMI, smoking, any chronic disease diagnosis, and recent use of central nervous system medications, as characteristics that independently contributed to fracture risk at any site. However, in this paper, relative weights given to each risk factor show that for hip fractures for example, age was the most important determinant followed by falls, which agrees with the results of our study. Our study was unable to identify the other risk factors found in THIN and QResearch [17] that add small additional predictive abilities, as we were only powered to find strong risk factors. However, in the THIN study [16], a simple scheme that only included age and weight found fracture risks similar to their more complex scheme. It is likely that falls did not add a large additional benefit to age and weight, as seen in our study, because of lack of recording of falls on GP medical records. Our results support the view that in fallers, fracture prediction tools which take into account a falls history may have advantages over the FRAX tool which currently does not incorporate falls [20].

We also showed, in agreement with all other studies, that age is the most important risk factor for fracture, despite the fact that age varied over a relatively narrow range in this study. Furthermore, we showed that height was associated with reported fractures, with taller women more likely to fracture. This has been shown previously for hip fracture [21] with the explanation suggested involving biomechanical parameters of hip axis length [22]. This is unlikely to be the explanation of the association with fractures in our cohort, as most were of the upper limb. It is possibly more to do with falling from a greater height, and a greater impact due to greater velocity, again reinforcing the importance of falls. Many other studies, using patient groups other than primary care-based populations agree with our results that low weight is an important predictor of fracture risk [23, 24], but we extend these results to suggest that falls is more important.

It is interesting that our results confirm that although age and height/weight are important risk factors for fracture risk, there was little evidence that other clinical risk factors used in FRAX such as previous or family history of fracture were associated with fractures. This is most likely to be because we were only powered to find strong risk factors. Other explanations include differences in the study population and methods of data collection. For example, studies used in the FRAX meta-analyses were prospective cohorts, while ours employed a cross-sectional analysis, suggesting that our data may be less robust.

Being a cross-sectional analysis means our study will suffer from bias, confounding and chance, and could be explained by reverse causality. In particular, the reported falls may predate the reported fracture. Nonetheless our study utilised a population-based cohort of elderly women from primary care and is roughly representative of the local area. Our response rate of 45.2%, while initially appearing low, is considered reasonable for a population-based recruitment strategy [25]. Alternative explanations for our finding that 69% of frequent fallers had no record of this with their GP could include false positive reporting by study participants, but we think this is unlikely.

A further limitation is the use of reported rather than verified fractures as the main outcome. This will reduce the strength of any association found, but is unlikely to be a source of bias. We were unable to include rheumatoid arthritis as a secondary cause of osteoporosis due to poor validity and this is likely to have reduced the strength of any potential association between secondary causes and fractures in our analysis. There is a concern that people are far more likely to remember falls where they injured themselves such as fracturing a bone, resulting in recall bias. Furthermore, there is the potential for a large temporal difference between fractures since aged 50 and reported falls over the past 5 years which may introduce bias. The estimation of quantification of the additional predictive ability of adding falls to the clinical risk factor model using a Fit Statistic isn't ideal, as this penalises models with increasing numbers of variables.

So in conclusion, our study has shown that age and falls are the most important risk factors for fracture. We estimate that a history of more than one fall per year is at least twice as important as height or weight. Furthermore, using self-reported falls data are essential as computerised GP records underestimate falls prevalence. A risk-factor assessment just using age and falls is likely to be a useful means for simple fracture risk assessment for women within primary care in the UK.

Key points.

In post-menopausal women from primary care, age and falls are the strongest risk factors for fracture.

Falling more than once per year is at least twice as important as other risk factors for fracture.

Use of self-reported falls data is essential as computerised GP records underestimate the prevalence of falls in post-menopausal women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks all the women participants and local GP practices that have contributed to COSHIBA.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

COSHIBA was funded via a Clinician Scientist Fellowship for Emma Clark from Arthritis Research-UK.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

References

- 1.Haaczynski J, Jakimiuk A. Vertebral fractures: a hidden problem of osteoporosis. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:1108–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boonen S, Laan R, Barton I, Watts N. Effect of osteoporosis treatments on risk of non-vertebral fractures: review and meta-analysis of intention-to-treat studies. Osteo Int. 2005;16:1291–98. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1945-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schott AM, Cormier C, Hans D. How hip and whole body BMD predict hip fracture in elderly women: the EPIDOS Prospective Study. Osteo Int. 1998;8:247–54. doi: 10.1007/s001980050061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, Borgstrom F, Strom O, McCloskey E. FRAX and its applications to clinical practice. Bone. 2009;44:734–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.01.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. A comparison of total hip BMD as a predictor of fracture risk: a meta-analysis. J Bone Min Res. 2005;20(Suppl. 1):S4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Min Res. 2005;20:1185–94. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Laet C, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteo Int. 2005;16:1330–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. A meta-analysis of prior corticosteroid use and fracture risk. J Bone Min Res. 2004;19:893–9. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, et al. A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 2004;35:375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. A family history of fracture and fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Bone. 2004;35:1029–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, et al. Smoking and fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteo Int. 2005;16:155–62. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Johnell O, et al. Alcohol intake as a risk factor for fracture. Osteo Int. 2005;16:737–42. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1734-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geusens P, van Geel T, van dan Berg J. Can hip fracture prediction in women be estimated beyond BMD alone? Therap Adv Musculoskel Dis. 2010;2:63–7. doi: 10.1177/1759720X09359541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Lamb SE, Gates S, Cumming RG. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database System Rev. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. CD007146(2), DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson PM, Sadigh S, Tillgren PE, Rehnberg C. Non-pharmaceutical prevention of hip fractures: a cost-effectiveness analysis of a community based elderly safety promotion programme in Sweden. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2008;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Staa TP, Geusens P, Kanis JA, Leufkens HGM, Gehlbach SH, Cooper C. A simple clinical score for estimating the long-term risk of fracture in post-menopausal women. Q J Med. 2006;99:673–82. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Predicting risk of osteoporotic fracture in men and women in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QFractureScores. BMJ. 2009;339:b4229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boissonnault WG. Collecting health history information: the accurary of a patient self-administered questionnaire in an orthopedic outpatient setting. Phys Therapy. 2005;85:531–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark EM, Ness AR, Tobias JH. Bone fragility contributes to the risk of fracture in children, even after moderate and severe trauma. J Bone Min Res. 2008;23:173–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Bergh JPW, van Geel TACM, Lems WF, Geusens PP. Assessment of individual fracture risk: FRAX and beyond. Curr Osteo Rep. 2010;8:131–7. doi: 10.1007/s11914-010-0022-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemenway D, Feskanich D, Colditz GA. Body height and hip fracture: a cohort study of 90,000 women. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:783–6. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faulkner KG, Cummings S, Black D, Palermo L, Gluer CC, Genant HK. Simple measurement of femoral geometry predicts hip fracture: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Min Res. 1993;8:1211–7. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White SC, Atchison KA, Gornbein JA, Nattiv A, Paganini-Hill A, Service SK. Risk factors for fractures in older men and women: the Leisure World Cohort Study. Gender Med. 2006;3:110–23. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(06)80200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stolee P, Poss J, Cook RJ, Byrne K, Hirdes JP. Risk factors for hip fracture in older home care clients. J Gerentol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:403–10. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reid C, Ryan P, Nelson M. GP participation in the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study (ANBP2) Clin Exp Pharma Physiol. 2001;28:666–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.