Abstract

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI 3-kinases) are activated by growth factor and hormone receptors, and regulate cell growth, survival, motility, and responses to changes in nutritional conditions (Engelman et al. 2006). PI 3-kinases have been classified according to their subunit composition and their substrate specificity for phosphoinositides (Vanhaesebroeck et al. 2001). The class IA PI 3-kinase is a heterodimer consisting of one regulatory subunit (p85α, p85β, p55α, p50α, or p55γ) and one 110-kDa catalytic subunit (p110α, β or δ). The Class IB PI 3-kinase is also a dimer, composed of one regulatory subunit (p101 or p87) and one catalytic subunit (p110γ) (Wymann et al. 2003). Class I enzymes will utilize PI, PI[4]P, or PI[4,5]P2 as substrates in vitro, but are thought to primarily produce PI[3,4,5]P3 in cells.

The crystal structure of the Class IB PI 3-kinase catalytic subunit p110γ was solved in 1999 (Walker et al. 1999), and crystal or NMR structures of the Class IA p110α catalytic subunit and all of the individual domains of the Class IA p85α regulatory subunit have been solved (Booker et al. 1992; Günther et al. 1996; Hoedemaeker et al. 1999; Huang et al. 2007; Koyama et al. 1993; Miled et al. 2007; Musacchio et al. 1996; Nolte et al. 1996; Siegal et al. 1998). However, a structure of an intact PI 3-kinase enzyme has remained elusive. In spite of this, studies over the past 10 years have lead to important insights into how the enzyme is regulated under physiological conditions. This chapter will specifically discuss the regulation of Class IA PI 3-kinase enzymatic activity, focusing on regulatory interactions between the p85 and p110 subunits and the modulation of these interactions by physiological activators and oncogenic mutations. The complex web of signaling downstream from Class IA PI 3-kinases will be discussed in other chapters in this volume.

1 Structural Organization of p85α/p110α

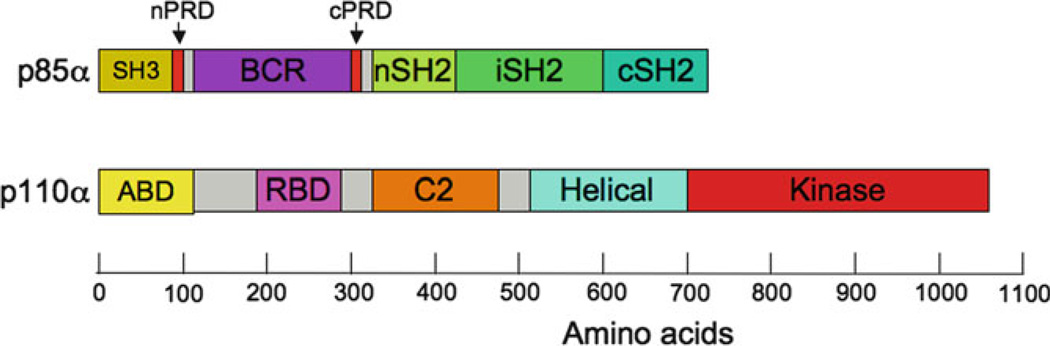

The p85 regulatory and p110 catalytic domains of Class IA PI 3-kinase are both multi-domain proteins (Fig. 1). The crystal structure of p110α (Huang et al. 2007) shows an N-terminal Adapter Binding Domain (ABD), which binds to the coiled-coil domain of p85 (the iSH2 domain). The ABD has an ubiquitin-like fold that makes a large hydrophobic contact with the iSH2 domain (Huang et al. 2007; Miled et al. 2007). The remainder of p110α consists of a Ras-binding domain, a C2 domain, a helical domain (found in all PI 3-kinase and formerly referred to as the PIK domain), and a kinase domain with a two-lobed structure typical of protein kinases; this organization is similar to that found in p110γ (Huang et al. 2007; Walker et al. 1999).

Fig. 1. Domain structure of p85α and p110α.

The p85α regulatory subunit contains Src-homology 3 (SH3), BCR-homology (BCR), Proline rich (PRD), and Src homology 2 (SH2) and domains. The inter-SH2 domain (iSH2) is an antiparallel coiled-coil that links the two SH2 domains. The p110α catalytic subunit contains the adapter binding domain (ABD), which binds to the iSH2 domain of p85, a Ras-binding domain (RBD), a C2 domain, a helical domain (formally called the PIK homology domain), and a kinase domain

The full-length p85 isoforms, p85α and p85β, consist of an SH3 domain, a Racbinding domain (the BCR homology domain) flanked by two proline-rich domains (nPRD and cPRD), and two SH2 domains (nSH2 and cSH2) linked by the inter-SH2 (iSH2) domain (Vanhaesebroeck et al. 2001). Three shorter regulatory subunits, p55γ and the p85α splice variants p55α and p50α, lack the SH3, nPRD, and BCR domains. The two p85 nSH2 and cSH2 domains share a similar specificity for tyrosine-phosphorylated motifs of the form YxxM (Songyang et al. 1993). While individual domains of p85α have been structurally characterized, as yet there is no structural data concerning the spatial organization of these domains within p85.

The iSH2 domain was predicted to be a long antiparallel coiled coil, based on sequence analysis (Dhand et al. 1994a) and subsequent site-specific spin labeling/electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy and molecular modeling of the nSH2-iSH2 fragment of p85α (Fu et al. 2003). A crystal structure of the isolated iSH2 domain (residues 431–600) bound to the ABD of p110α (Miled et al. 2007) shows a 115-Å long rod comprising two major helices (440–515 and 518–587). The C-terminal end of the iSH2 domain forms a short third helix (588–599); the extent of this third helix in intact p85α is not yet known. The presence of the p85α N- and C-terminal SH2 domains at the ends of an antiparallel coiled-coil suggests that the domains are relatively close to each other. The linker between the nSH2 domain and the iSH2 domain is only 10 amino acids long, and recent EPR data suggest that this short tether limits the range of mobility of the nSH2 domain relative to the iSH2 domain (Sen et al. 2010; see below). In contrast, the linker region between structurally defined helical regions of the iSH2 domain and the cSH2 domain (23 amino acids) is long enough to allow for considerable uncertainty as to their relative orientation. Isothermal calorimetry studies showed that the two SH2 domains of p85α can bind simultaneously to a peptide containing phosphotyrosine residues separated by 11 amino acids (O’Brien et al. 2000), and the nSH2 domain can bind to a phosphorylated Tyr688 in the C-terminal SH2 domain in the context of a p85/p110α dimer (Cuevas et al. 2001). While these studies suggest that the phosphotyrosine binding sites of the nSH2 and cSH2 domains can in some cases be close together, the range of motion and orientation of the two domains in the p85α/p110 dimer is not known.

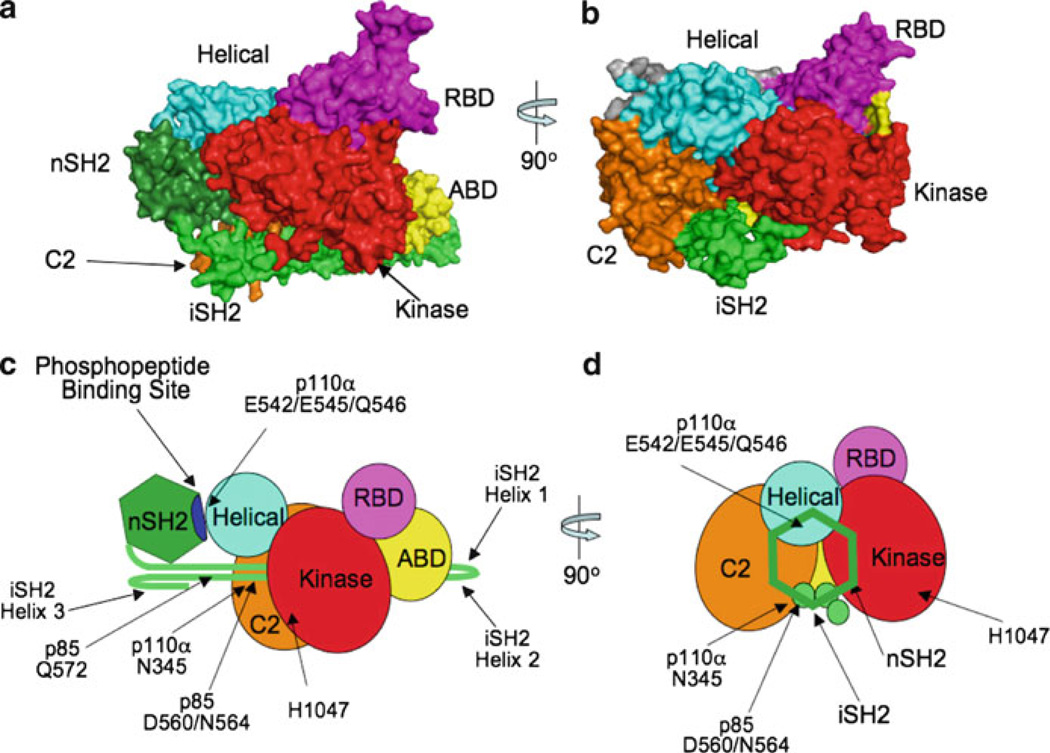

The crystal structure of p110α bound to an nSH2-iSH2 fragment of p85α (Huang et al. 2007) is shown in Fig. 1 in both space-filling and schematic views, from two orientations. Structures of the p110α ABD or intact p110α bound to the iSH2 domain of p85α show extensive hydrophobic interactions between the ABD and the iSH2 domain, involving seven helical turns in iSH2 helix 1 and three turns of helix 2 (Miled et al. 2007). The C2 domain and kinase domains of p110α drape over the iSH2 domain, with predicted hydrogen bonding between residue N345 in the C2 domain with residues D560 and N564 in helix 2 of the iSH2 domain. The helical domain contacts the kinase and C2 domains, and is located near the p85 SH2 domains and away from the ABD-iSH2 domain contacts. In the orientation shown in Fig. 2a, b, the Ras-binding domain is on top, separated from the iSH2 domain and making contacts with the kinase domain. The position of the p85α nSH2 domain is not seen in the crystal structure of wild-type p110α, but is visible in the structure of the p85 nSH2-iSH2 fragment dimerized with the H1047R mutant of p110α (Huang et al. 2007; Mandelker et al. 2009). The nSH2 domain makes contacts with the helical domain of p110α, as previously predicted (Miled et al. 2007), as well as with the kinase and C2 domains.

Fig. 2.

Space-filing views of the nSH2-iSH2-p110α[H1047R] crystal structure (Huang et al. 2007; Mandelker et al. 2009), facing the iSH2 domain from the side (a) or down its barrel with the nSH2 domain removed (b). (c, d) Schematic models of the same orientations. In (d), the nSH2 domain is shown only in outline, to allow the rest of the iSH2 domain and p110α to be seen. The sites of the oncogenic mutations in p85α (D560, N564 and Q572) and p110α (E542/E545/Q546 and H1047) are shown, as is the phosphopeptide binding site of the nSH2 domain

2 p85α Inhibits and Stabilizes p110

The p85α and p85β regulatory and p110α catalytic subunits of Class IA PI 3K were cloned in 1991 and 1992 (Escobedo et al. 1991; Hiles et al. 1992; Otsu et al. 1991; Skolnik et al. 1991). There was initially some confusion as to whether p85α activated or inhibited p110α. The catalytic subunit is active as a monomer when expressed in insect cells (Hiles et al. 1992). In contrast, p85α is required for p110α activity in mammalian cells; based on these latter data, Williams and coworkers proposed that p85α is a p110α activator (Klippel et al. 1994). Studies in yeast suggested that p85α is a p110α inhibitor, as expression of p85α rescues the lethal effects of p110α expression in S. pombe (Kodaki et al. 1994). Similarly, using recombinant monomeric p110α produced in insect cells, it was shown that p85α binding inhibits the activity of monomeric p110α by as much as 80% (Yu et al. 1998a). These data were reconciled with the discovery that monomeric p110α is heat labile, and is stabilized by dimerization with p85α (Yu et al. 1998a). Monomeric p110α rapidly loses activity when incubated at 37°C, and it undergoes rapid degradation when expressed as a monomer in mammalian cells. However, the p110α monomer is active when expressed in insect cells, which grow at 25°C. Similarly, the specific activity of overexpressed monomeric p110α in mammalian cells is increased 15-fold by culturing the cells at reduced temperature. These data explain the discrepancies in the earlier literature: the apparent activation of p110α by its co-expression with p85α in mammalian cells in fact reflects the stabilization of p110α in an inhibited, low activity state. The heat labile nature of monomeric p110α also explains the later observation that the homozygous deletion of p85α and p85β in MEFs leads to parallel losses of p110 expression (Fruman et al. 2000).

The stabilization of the p110α subunit by binding to p85α is not as yet understood. Several groups showed that the N-terminus of p110, the adapter-binding domain or ABD, binds to the coiled-coil domain of p85α, the iSH2 domain (Holt et al. 1994; Hu et al. 1993; Hu and Schlessinger 1994; Klippel et al. 1993). This interaction is necessary and sufficient for p110-p85α dimerization and for stabilization of p110α in mammalian cells, although it does not replicate physiological regulation of p110α (see below). Surprisingly, the role of regulatory subunit binding in p110α stabilization is supplanted by the linkage of epitope tags to the N-terminus of p110α; the degree of stabilization correlates with the size of the tag (Yu et al. 1998a). This explains the finding that a fusion of the p85α iSH2 domain with the N-terminus of p110α (the commonly used p110*) is constitutively active in mammalian cells (Hu et al. 1995). Based on more recent biochemical and structural data, this construct is unlikely to replicate ABD-iSH2 interactions. The ABD of p110α binds to residues near the hinge region of the rod-like iSH2 antiparallel coiled-coil, at the end furthest away from the two SH2 domains (Huang et al. 2007; Miled et al. 2007) (Fig. 2). In contrast, the p110* chimera links helix 3 of the iSH2 domain to the N-terminus of p110α, placing the p110α ABD at some distance from its normal binding site in the iSH2 domain. Thus, the iSH2 domain in p110* presumably stabilizes p110α by acting as a bulky N-terminal tag, and not by replicating ABD-iSH2 domain interactions. Consistent with this idea, Vogt and colleagues have found that an oncogenic mutant of p110α, p110α-H1047R, is not stabilized by a p110*-like linkage to the iSH2 domain (Zhao and Vogt 2008), whereas we find that p110α H1047R is stabilized by co-expression with the iSH2 domain in trans (J.M. Backer, unpublished observations).

The stabilization of p110α catalytic subunits (and presumably also p110β and p110δ) poses a problem for overexpression studies, since N-terminally tagged p110 will show a higher stability, and hence a higher constitutive activity, than wild-type p110 (Yu et al. 1998a). Whereas expression levels of wild type p110α are limited by the amount of available p85, this is not true for N-terminally tagged p110α. Unfortunately, recent data suggest that some C-terminal tags may inhibit the activity of p110α toward PI[4,5]P2 in vivo (Bart Vanhaesebroeck, personal communication). Thus, the definition of an activity-neutral tag for the study of p110 isoforms continues to pose a significant experimental problem.

The inhibition of p110 by p85 is an example of a widely used regulatory scheme in eukaryotic ells, in which regulatory subunits of kinases maintain enzyme activity at a low level, with subsequent activation of the enzyme by a release of inhibition. The best-studied example of this scheme is PKA, where R1 or R2 subunits inhibit the activity of the C subunits (Taylor et al. 2005). In PKA, the mechanism of disinhibition is dissociative: in the presence of cAMP, the binding between the regulatory and catalytic subunits is disrupted. However, for Class IA PI 3-kinase, this mechanism of disinhibition is impossible for two reasons. First, as discussed above, monomeric p110 is heat labile and would rapidly lose activity should p85 dissociate. Second, p85–p110α binding is extremely tight, and is essentially irreversible under cellular conditions (Woscholski et al. 1994). Thus, activation of p85/p110 dimers by upstream regulators must occur by an intramolecular conformational change, in which the subunits remain bound together and activator binding to p85 causes a conformational change in p110.

3 Activation of p85α/p110α Dimers by Phosphopeptides

Early studies on Class IA PI 3-kinases demonstrated an increase in PI 3-kinase activity in anti-phosphotyrosine or anti-receptor tyrosine kinase immunoprecipitates upon growth factor stimulation (reviewed in Cantley et al. 1991). With the demonstration that SH2 domains are binding sites for tyrosine phosphorylated proteins (Matsuda et al. 1991; Mayer et al. 1991; Moran et al. 1990), as well as the identification of relatively PI 3-kinase-specific phosphotyrosine motifs in receptor tyrosine kinases (Fantl et al. 1992; Songyang et al. 1993), it became clear that the production of PIP3 in vivo is mediated at least in part by the recruitment of PI 3-kinases to activated receptor tyrosine kinases or their substrates. This led to the demonstration that constitutive targeting of p110α to cell membranes by N-terminal myristylation or C-terminal isoprenylation is sufficient to produce constitutive increases in PIP3 production (Klippel et al. 1996). The preferred tyrosine phosphorylated peptide binding site for the p85α SH2 domains was defined by degenerate peptide library binding studies to be (P)YxxM (Songyang et al. 1993). A crystal structure of a phosphopeptide-bound p85α nSH2 domain shows a two-pronged socket binding mechanism, similar to that seen in the Src SH2 domain, in which the negatively-charged phosphotyrosine fits into a positively charged pocket, and the bulky methionine fits into a hydrophobic pocket (Nolte et al. 1996; Waksman et al. 1993).

With the development of antibodies against endogenous p85α, as well as methods to produce recombinant p85α and p110α in baculovirus (Gout et al. 1992; Woscholski et al. 1994), it was possible to directly examine the effect of p85α SH2 domain occupancy on the specific activity of PI 3-kinase, independently of effects on PI 3-kinase membrane recruitment. Initial studies showed that binding of p85α/p110α dimers to tyrosine phosphorylated IRS-1 or tyrosine phosphopeptides peptides from IRS-1, Polyoma middle T or the PDGF receptor causes a two- to threefold activation in vitro (Backer et al. 1992; Carpenter et al. 1993). Bisphosphopeptides activate PI 3-kinase with higher potency than corresponding monophosphopeptides (Carpenter et al. 1993; Herbst et al. 1994). p85α contains two SH2 domains, and a number of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins that bind p85α are known to have two or more tyrosine phosphorylated YXXM motifs (e.g., PDRF-R, IRS-1). This suggested that dual occupancy of both domains might lead to increased PI 3-kinase activation. Consistent with this model, individual mutation of the conserved FLRVES motif in the N-terminal or C-terminal SH2 domains of p85α leads to partial loss of phosphopeptide activation; mutation of both SH2 domains leads to a complete loss (Rordorf-Nikolic et al. 1995).

While bis-phosphopeptides lead to more potent activation of p85α/p110α dimers, the idea that the N- and C-terminal SH2 domains of p85α bind simultaneously to a single tyrosine-phosphorylated protein has been challenged. Biochemical studies showed that a bis-phosphorylated peptide from Polyoma MT binds to the p85α nSH2 domain, but not to the cSH2 domain, with enhanced affinity relative to a monophosphopeptide; a second noncanonical binding site for phosphotyrosine in the nSH2 domain was defined using NMR (Günther et al. 1996). Bis-phosphopeptides were also found to induce formation of higher order dimers between p85α/p110α holoeznymes; dimerization is independent of peptide concentration, suggesting that it does not involve direct bridging of SH2 domains in distinct p85α/p110α dimers (Layton et al. 1998). Finally, isothermal calorimetry experiments suggested that the mode of p85α binding to receptors containing two potential binding sites (e.g., the PDGF-R receptor) is concentration dependent: two distinct p85α molecules bind to a single bis-phosphopeptide when p85α is in excess, whereas both SH2 domains from a single p85α molecule bind to a single bis-phosphopeptide when peptide is in excess (O’Brien et al. 2000). It remains unclear whether PI 3-kinase binding to ligands like the tyrosine bis-phosphorylated PDGF receptor in vivo involves divalent interactions.

4 A Mechanism for Phosphopeptide Activation

A model for the regulation of p85α/p110α dimers by phosphopeptides emerged from biochemical studies, in which active monomeric p110α (produced in insect cells) was reconstituted with fragments of p85α, and its activity was measured in the absence and presence of tyrosine phosphopeptides (Yu et al. 1998b). These studies showed that although the iSH2-ABD contact is the major interaction responsible for formation of the p85α/p110α dimer, as previously shown by several groups (Holt et al. 1994; Hu et al. 1993; Hu and Schlessinger 1994; Klippel et al. 1993), the iSH2 domain is not involved in the regulation of p110α activity. First, although the iSH2 domain is sufficient to bind the p110α ABD, this binding has no affect on p110α activity. Regulation of p110α by tyrosine phosphopeptides was instead shown to specifically require the presence of the N-terminal SH2 domain: nSH2-iSH2 fragments of p85α (p85ni) inhibit p110 and the p85ni/p110α dimer is activated by phosphopeptide. In contrast, iSH2, iSH2-cSH2, and cSH2-iSH2 fragments bind but do not inhibit p110. Thus, p85ni is the minimal fragment of p85α that confers phosphopeptide regulation of p110 (Yu et al. 1998b).

Second, NMR and EPR studies on the structure and mobility of the iSH2 domain showed that the iSH2 domain is rigid and conformationally unresponsive to SH2 domain occupancy (Fu et al. 2003, 2004; O’Brien et al. 2000). Based on these data, it was proposed that the iSH2 domain is a rigid tether for p110, holding the subunits together and enabling a second regulatory contact between the nSH2 and an unidentified region of p110α (Fu et al. 2004). Subsequent activation of the p85α/p110α dimer would involve a disruption of this inhibitory interface by binding of a phosphoprotein to the SH2 domain.

While these data suggested an inhibitory nSH2-iSH2 contact, the site of this contact was not known. A potential clue to the site of interaction emerged from studies by Samuels et al., which identified oncogenic mutants of p110α from human tumor samples (discussed in more detail below) (Samuels et al. 2004). Sporadic mutations are scattered over the length of p110α, but two hotspots account for nearly 80%of themutations: an H1047R mutant in the C-terminus of p110α, and a cluster of 3 change of-charge mutations (E542K, E545K, Q546K) in the helical domain of p110α. Could these hotspots indicate the site of the inhibitory nSH2-p110α contact? If so, then it seemed likely that the mutations would be at residues conserved between Class IA catalytic subunit isoforms (p110α/β/δ), since p85α binds to and inhibits all three isoforms. However, whereas the acidic cluster in the helical domain is conserved in all three p110 isoforms, H1047 is not found in the kinase domains p110β or p110δ, where residues corresponding to H1046H1047 are replaced with LR. Thus, the helical domain acidic cluster seemed the more likely site of nSH2-p110α contact.

This hypothesis was tested using an in vitro reconstitution approach (Miled et al. 2007). Helical domain mutants of p110α (E542K, E545K, E546Q) bind p85ni but are not inhibited, nor are p85α/p110α-E545K dimers additionally activated by phosphopeptide. In contrast, although the H1047R mutant has increased specific activity as compared to wild-type p110α, p85α/p110α-H1047R dimers are additionally activated by phosphopeptide (Carson et al. 2008), consistent with the observation that p110α-H1047R is inhibited by p85ni (J.M. Backer and R.L.Williams, unpublished observations). Thus, the helical domain appeared to be the site of the inhibitory nSH2 domain contact. Miled et al. next reasoned that the acidic patch in the helical domain was likely to interact with basic residues on the surface of the nSH2 domain. If so, then a basic-to-acidic mutation in the nSH2 domain might reduce the inhibition of wild-type p110, but restore the inhibition of the helical domain mutants. In fact, it was shown that K379E and R340E mutants of p85ni exhibited a loss of inhibition of wild-type p110. Additional experiments showed that the K379E mutant of p85ni restores the inhibition of the E545K mutant of p110, indicative of contacts between basic residues in the nSH2 domain and the acidic patch in the helical domain.

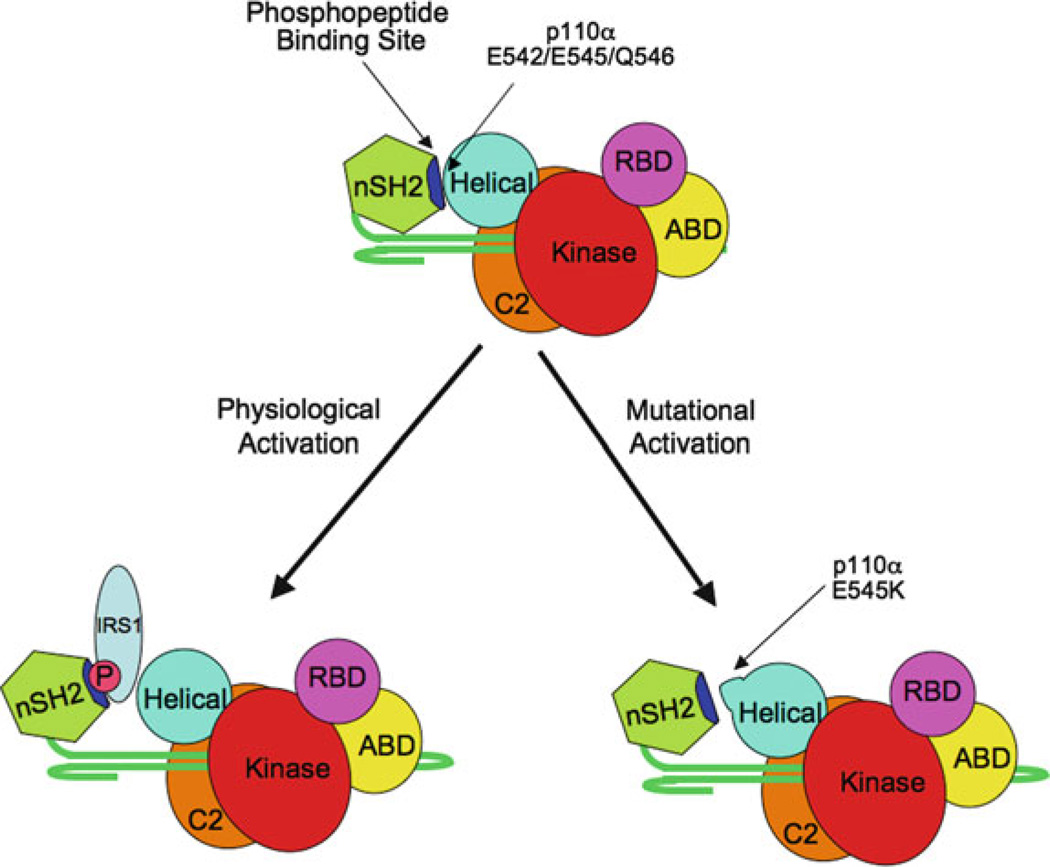

These data shed light on both the physiological activation of p85α/p110α by tyrosyl phosphoproteins, as well as the mechanism of oncogenic activation in the helical domain mutants (Fig. 3). The nSH2 basic residues whose mutation to Glu reduce the inhibition of wild-type p110α (K379 and R340) lie adjacent to the phosphopeptide-binding site of the nSH2 domain. One can readily see how the binding of the tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins to the nSH2 domain would disrupt contacts between these residues and the helical domain of p110α. In the cancer-related p110α helical domain mutations, this contact is already disrupted. Thus, the helical domain mutants of p110α found in human cancer mimic the physiological disruption of p110α inhibition caused by phosphotyrosine protein binding to the nSH2 domain of p85α. More recent data suggest that helical domain mutations may have additional effects in the context of transformation (Zhao and Vogt 2008) (discussed below).

Fig. 3. Models of physiological and oncogenic activation of p85/p110 dimers.

The models show a schematic of p110α bound to the nSH2-iSH2 fragment of p85. In normal cells, phosphoprotein binding to the nSH2 domain disrupts the inhibitory interface with the helical domain of p110α. In transformed cells, mutations of residues in the acidic patch in the helical domain (for example E545K) constitutively disrupt nSH2-helical domain interactions, leading to the deregulation of the enzyme

Given that the nSH2 phosphopeptide binding site contacts the E542/E545/Q546 acidic patch in the helical domain of p110α, the nSH2 domain presumably must move away from the helical domain to accommodate the binding of tyrosine phosphorylated activators. Recent studies suggest that the nSH2 domain shows considerable mobility relative to the iSH2 domain, at least in the context of an isolated p85α (Sen et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2009; see below). Biochemical data also suggests that the ability of nSH2 domain to move about the proximal end of the iSH2 domain is necessary for PI 3-kinase activation, as introduction of an engineered disulfide bond between the nSH2 and iSH2 domains produces a mutant than inhibits p110, but cannot be activated by phosphopeptides (H. Wu and J.M. Backer, unpublished observations). A similar model has been proposed by Hale et al. (2008) for the activation of p85β /p110α dimers by the NS1 protein from Influenza A. NS1 binds to the C-terminal end of the p85β iSH2 domain, including helix 3, and the authors propose that binding of NS1 to this region may sterically force the nSH2 domain into a conformational that disrupts its inhibitory contacts with the helical domain of p110.

As noted above, maximal activation of intact p85α/p110α dimers by phosphopeptides requires functional nSH2 and cSH2 domains (Rordorf-Nikolic et al. 1995). Given that an iSH2-cSH2 fragment of p85α binds but does not inhibit p110α (Yu et al. 1998b), the mechanisms of activation by the C-terminal SH2 domain must be different. Interestingly, phosphopeptide binding to the cSH2 domain contributes to p110α activation only within the context of full-length p85α/p110α dimers, but not when p110α is dimerized with the nSH2-iSH2-cSH2 construct; a disabling mutation of the nSH2 domain only partially abolishes phosphopeptide activation of p85α/p110, whereas it completely abolishes activation of p110α bound to the nSH2-iSH2-cSH2 construct (Yu et al. 1998b). This means that activation of p110α dimers by occupancy of the cSH2 domain requires the presence of the N-terminal domains of p85α (the SH3, proline rich and BCR-homology domains). Presumably, these domains position the cSH2 domain so that it makes direct contacts with p110, or affect inhibitory contacts between p110α and other domains of p85α. An example of this latter mechanism was described by Cuevas et al. (2001), who suggested that the tyrosine phosphorylation of a site in the cSH2 domain (Y688) could interact with the nSH2 domain, leading to PI 3-kinase signaling to Akt activation in cultured cells. However, in this case the activation occurs through phosphorylation rather than through cSH2 domain occupancy.

A mechanistically independent role for the cSH2 domain was also suggested by Chan et al. (2002), who showed that Ras-dependent Akt activation is blocked by expression of a p85α fragment consisting of helix 3 of the iSH2 domain, the iSH2-cSH2 linker, and the cSH2 domain. A truncation mutant identified in a Hodgkin’s disease patient (a frame shift that truncates p85α at residue 635 in the cSH2 domain, and adds 25 unrelated amino acids) also leads to increased Akt activation and transformation in cultured cells (Jucker et al. 2002), despite the fact that this construct appears to inhibit p110α in vitro to the same extent as wild type p85α (JM Backer, unpublished observations). These data suggest that the deletion of the cSH2 domain may activate PI 3-kinase signaling in vivo by a mechanism that does not involve the inhibition of p110 by p85α.

5 Activation of p85/p110 by GTPases

Class I PI 3-kinases are activated by the binding of activated (GTP-bound) small GTPases. Activated Ras binds directly to the RBD of the catalytic subunit of both Class IA and IB PI-3 kinase. While all four p110 isoforms can bind Ras, only p110α and p110γ have been clearly shown to be activated by Ras in vitro (Jimenez et al. 2002; Pacold et al. 2000; Rodriguez-Viciana et al. 1996; Rubio et al. 1997). This does not mean that Ras binding is not involved in signaling by p110β and p110δ, since an increase in membrane association could lead to increased PIP3 production in vivo that might not be detected in vitro. For example, p110β and p110δ but not p110α are recruited to Ras in redox-stimulated cells (Deora et al. 1998). In the case of p110γ, the crystal structure of the GTP-Ras-p110γ complex shows that activated Ras binding to the RBD involves both the Switch I and II domains of Ras. Ras binding causes a substantial shift in the position of a number of helices near the activation loop, consistent with an allosteric activation mechanism of p110γ activation (Pacold et al. 2000). A study of knock-in mice expressing RBD mutants of p110α has clearly shown that Ras-p110α binding is required for normal lymphatic development, and for tumorigenesis by activated mutants of K-ras (Gupta et al. 2007; Ramjaun and Downward 2007).

Binding of activated (GTP-bound) forms of the small GTPases Cdc42 or Rac activates p85α/p110α dimers in vitro (Bokoch et al. 1996; Tolias et al. 1995; Zheng et al. 1994); activation of p85α/p110β or p85α/p110δ dimers has not been assessed. Rac and Cdc42 bind to the BCR homology domain of p85α (Beeton et al. 1999), but the mechanism by which this binding affects p85α/p110α activity is not known. The BCR homology domain is so named because of homology to the Rho-GAP domain of the BCR gene product (Diekmann et al. 1991). A mutagenesis analysis of the BCR homolog β-chimaerin identified a number of residues necessary for Rho-GAP activity that are not conserved in the p85α BCR domain (Ahmed et al. 1994). Alternatively, another group has found that p85α does have GTPase activity toward Rac and Cdc42, as well as toward Rab5 and Rab4, but not Rab 11 (Chamberlain et al. 2004).

The original classification scheme for Class I PI 3-kinases suggested that p85α dimers with p110α, p110β, or p110δ are regulated primarily by receptor tyrosine kinases, whereas dimers of p101 or p87 with p110γ are regulated by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). This division of labors has been recently questioned, with the demonstration that p85α/p110β dimers are also regulated primarily by GPCRs (Guillermet-Guibert et al. 2008).

The activation of p85/p110β dimers by Gβγ-subunits was first noted in the 1997 by Kurosu et al. (1997), who identified a Gβγ-stimulated PI 3-kinase from rat liver as p85/p110β. The in vitro activation of p110β by Gβγ occurs in the absence or presence of p85; in the latter case, Gβγ activation is synergistic with phosphopeptide activation (Maier et al. 1999). In a strain of NIH 3T3 cells expressing undetectable levels of p110β, expression of p110β is required for LPA-stimulated activation of Akt (Murga et al. 2000). While these early studies suggested that p85/p110β dimers could respond to Gβγ, recent evidence suggests that p85/p110β dimers may in fact be unresponsive to receptor tyrosine kinases and primarily regulated by GPCRs. In MEFS expressing a kinase-dead p110β knock-in, or in the livers of conditional p110β knockout animals, signaling is normal in response to ligands for receptor tyrosine kinases, such as insulin or IGF-I, but defective in response to GPCR ligands such as LPA or S1P (Ciraolo et al. 2008; Jia et al. 2008). In macrophages, which also express the GPCR-regulated p110γ, both p85/p110β and p101/p110γ dimers respond to a similar range of GPCR ligands, and knockout or inhibition of both isoforms is required to completely inhibit GPCR-mediated activation of Akt (Guillermet-Guibert et al. 2008). The finding that p85/p110β dimers are responsive to GPCRs explains a number of data in the recent literature using knockouts, kinase-dead knock-ins, or isoform-specific PI 3-kinase inhibitors to evaluate specific signaling by distinct p110 isoforms. For example, in myotubes or adipocyte cell lines, similar amounts of p110α and p110β are bound to IRS-1, but pharmacological inhibition of p110β has minimal affect on IRS-1-associated PI 3-kinase activity or insulin signaling (Knight et al. 2006). Similarly, p110α is recruited preferentially to IRS-1 as compared to p110β in insulin-stimulated fat, muscle and liver (Foukas et al. 2006). These data are consistent with the idea that p110β is primarily regulated by GPCRs.

From a mechanistic point of view, however, we have very little insight into why p110β is regulated differently from p110α, or presumably p110δ. p110β is inhibited by p85 in vitro (H. Dbouk and JM Backer, unpublished observations), and p85/p110β dimers are activated by tyrosine phosphopeptides in vitro (Maier et al. 1999). The helical domain acidic patch required for regulation of p110α (Miled et al. 2007) is conserved in p110β. Thus, all the elements for SH2-mediated regulation of p110β would seem to be in place. This suggests that p110β is inhibited by nSH2-helical domain contacts, making it surprising that p85/p110β dimers are not activated by binding to tyrosine-phosphorylated IRS-1 (Knight et al. 2006). The failure of p110β-bound p85 to bind to tyrosine phosphorylated IRS-1, even in tissues where p110β is abundant, is also unexplained (Foukas et al. 2006).

Finally, little is known about how Gβγ interacts with p85/p110β. As mentioned above, Gβγ activation of Akt has been observed in cells expressing p110β without p85, and p110β is activated in the absence or p85 in vitro, suggesting that Gβγ can interact directly with the p110β catalytic subunit (Maier et al. 1999; Murga et al. 2000). p110β-mediated activation of Akt is blocked by overexpression of a construct comprising residues 34–349 of p110β, which contains the RBD flanked by truncated ABD and C2 domains (Kubo et al. 2005), but a more thorough definition of the Gβγ-p110γ binding site is still wanting.

p110β was identified in a proteomics analysis of proteins that bind to the activated form of Rab5, the early endosomal small GTPases (Christoforidis et al. 1999). The binding site for this interaction in p110β has not been established, nor has it been shown whether Rab5 binding to p85/p110β dimers increases PI 3-kinase activity. A possible endosome-specific function for p110β was suggested by the finding that early endosomal PIP3 can be converted by the sequential action of phosphoinositide phosphatase to the functionally important early endosomal lipid PI[3]P (Shin et al. 2005). In addition, a role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis has been suggested by studies showing a marked internalization defect in MEFs derived from mice in which p110β expression is knocked out or significantly decreased (Ciraolo et al. 2008; Jia et al. 2008). This may be consistent with the fact that Rab5-associated p110β is found in clathrin coated vesicles but not early endosomes (Christoforidis et al. 1999). It is intriguing to note that the internalization defect in p110β-deficient MEFs is rescued by kinase-dead mutant of p110β (Ciraolo et al. 2008; Jia et al. 2008), suggesting that the Rab5-p110β interaction may not involve regulation of p110β lipid kinase activity, but rather the regulation of an as yet undefined scaffolding function of p110β.

6 Activation by Binding to p85 SH3 and Proline-Rich Domains

The SH3 domain of p85α binds to proline-rich ligands of the general form RXLPPRPXX or XXXPPLPXR; the two types of ligand may bind in opposite orientations (Koyama et al. 1993). At present, nothing is known about the position of the p85α SH3 domain relative to the rest of p85α or p110, although in vitro binding studies show that the N-terminal proline rich sequences from p85α can interact with the p85α SH3 domain (Kapeller et al. 1994). This suggests that the SH3 domain may fold forward toward the BCR domain, which is flanked by the two proline-rich domains. If this hypothesis is correct, then the disruption of intramolecular SH3-proline-rich domain interactions might provide an activation mechanism for PI 3-kinase. Several studies have suggested that p85α/p110 dimers are activated by either binding of proline-rich peptides to the p85α SH3 domain, including the proline-rich motifs from the FAK tyrosine kinase (Guinebault et al. 1995) and the influenza virus protein NS1 (Shin et al. 2007a, b). However, as discussed above, activation of PI 3-kinase by influenza virus may also involve binding between NS1 and the C-terminal end of the p85β iSH2 domain (Hale et al. 2008). Similarly, addition of recombinant SH3 domains from Src-family kinases activates p85/p110 dimers in vitro (Pleiman et al. 1994), and PI 3-kinase activation by the binding the SH3 domains of Grb2 has been demonstrated in IGF-1-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cells (Imai and Clemmons 1999). These data suggest that binding of either the SH3 or proline rich domains of p85α lead to PI 3-kinase activation, perhaps by disrupting an inhibitory intramolecular SH2-PRD interaction.

7 Regulation by Autophosphorylation

Class I PI 3-kinases possess protein as well as lipid kinase activity. Ser608 in the iSH2-cSH2 linker region of p85α is a substrate for p110-mediated phosphorylation, which inhibits PI 3-kinase activity in vitro (Dhand et al. 1994b). This inter-subunit phosphorylation presumably represents a form of negative feedback regulation, as Ser608 phosphorylation is increased in response to stimulation by agonists like insulin or PDGF that increase Class IA activity (Foukas et al. 2004). However, evaluation of the role of this residue in vivo has been difficult, as mutation to either Ala or Glu decreases PI 3-kinase activity (Foukas et al. 2004). Interestingly, p85α-Ser608 phosphorylation is more robust in dimers with p110α as opposed to p110β (Beeton et al. 2000; Foukas et al. 2004); phosphorylation by p110δ was not tested. Phosphorylation of the corresponding residue (Ser602) in p85β has not been studied. In contrast, both p110β and p110δ undergo inhibitory C-terminal autophosphorylation, at residues S1070 and S1039, respectively (Czupalla et al. 2003; Vanhaesebroeck et al. 1999), whereas p110α autophosphorylation is not robust (Boldyreff et al. 2008; Dhand et al. 1994b). Thus, distinct Class IA PI 3-kinase isoforms all undergo inhibitory autophosphorylation, although at different sites and on different subunits.

8 Oncogenic Mutation of p85α and p110

Studies over the past five years have identified mutations in p85α and p110α that clearly define PI 3-kinase as an oncogene in human cancer. The landmark study by Samuels et al. examined lipid kinases in human colon, brain, gastric, breast and lung tumors (Samuels et al. 2004). Mutations were commonly found in p110α, but not in p110β, p110δ or p110γ. The vast majority of sites involve mutation of H1047 to Arg in the catalytic domain (33%), and E542, E5445 or Q546 to Lys in the helical domain (47%). Less frequent sites of mutation are in the C2 domain and the ABD. Multiple subsequent studies have identified these mutants in p110α from an ever-widening number of malignancies (reviewed in Liu et al. 2009). In a summary of series examining more than 100 patient samples, p110α mutations are found in 25% of breast tumors, 22% of endometrial tumors%, 17% of urinary tract tumors, 14% of large intestine tumors, 10% of cervical and upper aerodigestive tract tumors, and at lower frequencies in other tumors types (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic).

For the common E545K and H1047R mutants, as well as for the less common G106V, C420R, E453Q, E542K, and M1043I mutants, an increase in catalytic activity has been demonstrated in vitro (Carson et al. 2008; Ikenoue et al. 2005). Introduction of p110α mutants into chick fibroblasts or human mammary endothelial cells causes increased levels of Akt phosphorylation, transformation (Ikenoue et al. 2005; Isakoff et al. 2005; Kang et al. 2005; Zhao et al. 2005), tumor formation in the chick chorioallantoic membrane assay and in mice (Bader et al. 2006; Samuels et al. 2005; Zhao et al. 2005), and growth-factor independent growth in hematopoietic cells (Horn et al. 2008). In chick fibroblasts, a gradient of transforming efficiency was noted, and it was possible to subdivide p110α mutants into strongly (H1047R, N345K, C420R, P539R, E542K, E545K, E545G, Q546K, Q546P, H1047L, H1047R), moderately (E545A, T1025S, M1043I, M1043V, H1047Y), and weakly (R38H, K111N) transforming (Gymnopoulos et al. 2007).

It is surprising that mutants in other p110 catalytic subunits have not been identified. Two studies on the transforming potential of p110β,δ, and γ reached divergent conclusions: Kang et al. found that, in contrast to p110α, overexpression of wild type p110β,δ or γ is sufficient to cause transformation of avian fibroblasts (Kang et al. 2006). p110γ already contains an Arg residue at the site homologous to H1047R in p110α, but its mutation to His does not appear to alter p110γ activity (Kang et al. 2006). The authors proposed that given the transforming capacity of these isoforms in wild type state, their contribution to oncogenesis might be primarily via changes in expression as opposed to mutation. In contrast, Zhao et al. found that p110β is poorly transforming in mammary epithelial cells, even when the equivalent of the p110α E545K hotspot mutant (E552K) is introduced (Zhao et al. 2005). Given the differences in the systems used, the potential for transformation by modulation of p110β, δ and γ expression deserves further study.

Mutations in the p85α regulatory subunit have been described in murine and human cancers. The first mutants to be discovered were deletions or truncations in the C-terminal end of the iSH2 domain. Jimenez et al. described the fusion of p85α with a non-catalytic fragment of the Eph tyrosine kinase, which results in the termination of p85α at residue 571 (Jimenez et al. 1998). Expression of either the p85α-Eph fusion or the truncated p85α(1–571) leads to increased PI 3-kinase signaling and a modest increase in transformation in cultured cells. Philp et al. described the replacement of residues Met582–Asp605 of p85α with Ile (Philp et al. 2001), and Jucker et al. described a missense mutation resulting in the substitution of 25 unrelated amino acids after residue 635, in the cSH2 domain of p85α (Jucker et al. 2002); these mutations also lead to increased Akt activation and PIP3 production in cultured cells. Recent sequencing efforts in glioblastoma and colon cancer have identified additional point mutants and small deletions, most clustered in the iSH2 domain and the cSH2 domain (CGART 2008; Jaiswal et al. 2009; Parsons et al. 2008). A number of these mutants lead to increased PI 3-kinase activity, and Akt signaling, survival and transformation in BaF3 cells (Jaiswal et al. 2009).

8.1 Helical Domain Mutants: Disruption of the nSH2-Helical Domain Interface

The mechanism by which helical domain mutants lead to activation of p110α has been discussed above in the section on phosphopeptide activation of p85α/p110α dimers. Charge change mutations in a patch of acidic residues on the helical domain surface (E542K, E545K and Q546K) are proposed to disrupt an inhibitory contact with the nSH2 domain of p85α, mimicking the disruption of this interface that would occur with physiological SH2 domain occupancy (Miled et al. 2007). Transformation by helical domain is blocked by an RBD mutant (K277E) that disrupts Ras binding (Zhao and Vogt 2008), which is consistent with a previous study showing that phosphopeptide activation of p85α/p110α facilitates subsequent activation by Ras (Jimenez et al. 2002). Surprisingly, the E545K mutant causes increased transformation even in the context of an ABD truncation (residues 1–72) that abolishes p85α binding, suggesting that this mutation might have some effects independent of the disruption of inhibition by p85α (Zhao and Vogt 2008). However, it is important to note that the ABD truncation also causes a significant increase in transformation by wild type p110α, to a level that is only slightly less than that seen with the truncated helical domain mutant. This would suggest that in the context of the ABD truncation, the additional activating effect of the helical domain mutant is small relative to its effect on wild type p110α.

8.2 The Kinase Domain Mutant H1047R

The H1047R mutant of p110α is inhibited by p85α (Y. Yan and J.M. Backer, unpublished observations), and p85α/p110-H1047R dimers are activated by phosphopeptides (Carson et al. 2008), suggesting that this mutation is mechanistically distinct from helical domain mutants. Consistent with these data, the H1047R mutant is additive with the E545K mutant for Akt activation and transformation in avian fibroblasts (Zhao and Vogt 2008). Unlike the E545K mutant, the H1047R mutant is unaffected by mutation of the Ras-binding domain, and is not activated by Ras-GTP binding (Chaussade et al. 2009; Zhao and Vogt 2008). These data led to the proposal that the H1047R mutant mimics the effect of Ras-GTP binding to the RBD of p110α. Surprisingly, the transforming effects of the H1047R mutant are abolished by deletion of the ABD, to levels much lower than were seen in a similarly deleted wild type p110α (Zhao and Vogt 2008). The reason for this requirement for the p85-binding domain, which is not seen with wild type or E545K p110α, is not clear.

A crystal structure of the H1047R hotspot mutant of p110α has been recently solved (Mandelker et al. 2009). The R1047 residue is oriented at a 90° angle from the position of H1047 in the wild type enzyme, and leads to changes in the conformation of two loops (864–874 and 1050–1062). The net effect of the mutation is predicted to increase the ability of the kinase to interact with cellular membranes; this is also suggested by biochemical data showing a greater sensitivity to variations in membrane lipid composition than wild type p110α during in vitro kinase assays. If a major effect of Ras binding to p110α is to enhance its association with cellular membranes (see below), then this model for the enhanced activity of p110αH1047R would be consistent with its insensitivity to mutations in the Ras binding domain.

8.3 p110α Mutations Disrupting the C2-iSH2 Domain Interface

The crystal structure of p110α identified a previously unappreciated contact between the C2 domain of p110α and the iSH2 domain of p85α (Huang et al. 2007). In particular, hydrogen bonding was predicted between p110α residues N345 and p85α iSH2 domain residues D560 and N564. Mutation of p110α N345 to Lys had previously be shown to induce transformation in avian fibroblasts, suggesting that disruption of the contact would lead to activation of p110α (Gymnopoulos et al. 2007). More recently, mutations at residues D560 and N564, as well other p85α residues near the C2-iSH2 domain interface, were discovered in human glioblastoma and colon cancer samples (CGART 2008; Jaiswal et al. 2009; Parsons et al. 2008). Analysis of the naturally occurring D560Y, N564D, D569Y/N564D, and DYQL579 mutants show that they bind but fail to inhibit p110α, β or δ, and lead to enhanced cell survival, Akt activation, anchorage independent cell growth, and oncogenesis (Jaiswal et al. 2009).

These data all point to the C2-iSH2 contact as an important inhibitory interface, whose mutation leads to increased constitutive PI 3-kinase activity and cellular transformation. However, unlike the nSH2-helical domain interface that is modulated during phosphoprotein regulation of PI 3-kinase, it is not yet known whether the C2-iSH2 domain interface is regulated under normal conditions. Furthermore, it is not yet known whether the loss of inhibition due to mutations at this site are due to direct conformational effects on p110α, as opposed to indirect effects due to a loosening of the iSH2-p110α coupling that might secondarily affect nSH2-helical domain interactions.

8.4 p85α Mutations Disrupting the C2-iSH2 Domain Interface

Interestingly, recent data suggest that the iSH2 truncation and deletion mutants described by Jimenez et al. (1998) and Philp et al. (2001), discussed above, may also exert their effects by disrupting the iSH2-C2 domain interface. A number of hypotheses as to the mechanism of PI 3-kinase activation by these mutations have been proposed. Foukas et al. (2004) noted that these mutants cause the loss of Ser608, whose transphosphorylation by p110α had been shown to cause an inhibition of PI 3-kinase lipid kinase activity (Dhand et al. 1994b). The authors proposed that the loss of this inhibitory phosphorylation site would lead to constitutive elevated activity in vivo. However, Shekar et al. compared the inhibition of p110α in vitro by an nSH2-iSH2 construct (residues 321–600) as opposed to a truncated version of this construct (residues 321–572) (Shekar et al. 2005). Whereas the nSH2-iSH2 construct inhibits p110α, even though it did not contain Ser608, truncation of the iSH2 domain at residue 572 causes a significant loss of p110α inhibition. Thus, while the loss of the inhibitory Ser608 site might modulate the level of PI 3-kinase activation in vivo, truncation of the iSH2 domain at residue 572 causes a loss of inhibition independent of the removal of Ser608.

A second hypothesis was based on the finding that introduction of spin labels into the C-terminal end of the iSH2 domain, the region that is deleted in the p85α (1–572) truncation, has pronounced relaxation effects on a single face of the nSH2 domain (Shekar et al. 2005). The authors interpreted the data as showing a contact between the nSH2 domain and the C-terminal iSH2 domain, and proposed that these contacts were required to orient the nSH2 domain so as to make inhibitory contacts with p110α. However, subsequent studies on the nSH2-iSH2 fragment of p85α show that the nSH2 domain is in fact highly mobile with respect to the iSH2 domain. 15N NMR relaxation methods were used to measure the rotational dynamics of the nSH2 domain within the nSH2-iSH2 construct, and defined an apparent rotational correlation time of 12.7 ± 0.7 ns for the nSH2 domain (Wu et al. 2009). These data are similar to experimental measurements for isolated SH2 domains (6.5–9.2 ns) and quite different from hydrodynamic calculations for several proposed nSH2-iSH2 geometries (45–52 ns) (Bernado et al. 2002; Farrow et al. 1994; Fushman et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 1998). Pulsed EPR measurements and molecular modeling of spin-labeled nSH2-iSH2 showed that the motion of the nSH2 domain is restrained to a torus-like distribution around the proximal end of the iSH2 domain (Sen et al. 2010). Thus, the nSH2 domain moves in a hinge-like manner, and not like a ball on a string; this restricted motion presumably explains why relaxation effects from iSH2 spin labels were only seen on one face of the nSH2 domain in the earlier study (Shekar et al. 2005). Similar results were obtained for the motion of the nSH2 domain in the context of full-length p85α (Sen IK, Wu H, Backer JM and Gerfen GJ, unpublished observations). Taken together, these data do not support a model in which truncation of the iSH2 domain relieves a conformational constraint on the nSH2 domain.

A third hypothesis was proposed by Huang et al., based on the discovery of a close contact between the C2 domain of p110α and the iSH2 domain of p85α (discussed above) (Huang et al. 2007). The authors proposed that the loss of residues 572–600 in the truncation mutant described by Jimenez et al. (1998) might destabilize the iSH2 domain coiled-coil at the C2 domain contact sites (near residues D560 and N564). This hypothesis was directly tested by Wu et al. (2009), who showed that wild type p110α is inhibited efficiently by the wild type nSH2-iSH2 construct but not by a construct truncated at residue Q572. In contrast, the p110α-N345K mutant shows the same degree of partial inhibition by either full-length nSH2-iSH2 or a construct truncated at residue Q572. These data suggest that the Q572 truncation has no phenotype when paired with a mutant p110α that is incapable of forming the C2-iSH2 domain contact. In vivo data further supported this hypothesis. Either truncation of the nSH2-iSH2 fragment at Q572, or mutation of D560 and N565 to Lys, leads to constitutive activation of Akt and S6K1 and increased transformation, but no additive effects are seen in a truncated D560K/N565K construct. Similarly, the p1110α-N345K mutation leads to increased rates of transformation as compared to wild type p110α (Gymnopoulos et al. 2007), but cells co-transfected with p110α-N345K plus wild-type, truncated, D560K/D565K, or truncated D560K/D565K mutants all show similar rates of transformation. These data suggest that truncation of p85α at residue Q572, or mutation of p85α residues D560K/N565K, both lead to constitutive PI 3-kinase activation by disrupting the inhibitory C2-iSH2 domain interface identified by Huang et al. (2007).

9 Regulation of p85/p110 In vivo: Activation Versus Translocation

PI 3-kinase must interact with cellular membranes in order to reach their phospholipids substrates. Constitutive membrane association of p110α catalytic subunits linked to N-terminal myristylation motifs or C-terminal CAAX motifs, leads to large increases in intracellular PIP3, Akt phosphorylation, and cellular transformation (Klippel et al. 1996). Since Class I PI 3-kinase has substantial activity under basal conditions (Beeton et al. 2000), membrane recruitment of PI 3-kinase leads to increased PIP3 production even in the absence of changes in PI 3-kinase specific activity. However, as described above, PI 3-kinases are also directly activated by allosteric interactions with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins and GTP-bound small Rac (Backer et al. 1992; Bokoch et al. 1996; Carpenter et al. 1993; Tolias et al. 1995; Zheng et al. 1994). These activations can be measured in vitro, independently of membrane recruitment, and reflect an increase in enzyme specific activity.

The allosteric activation of PI 3-kinases in vitro is not large (in the range of two-to fivefold). Given the magnitude of these changes in activity, there has been some question as to whether membrane translocation is sufficient to drive most PI 3-kinase dependent processes, and whether increases in catalytic activity play an important role in PI 3-kinase signaling. In this regard, the oncogenic potential of the helical domain p110α is informative. The helical domain mutants disrupt the inhibitory interface that is regulated by SH2 domain occupancy, and lead to an approximately twofold increase in activity in vitro (Carson et al. 2008). These mutants have normal SH2 domains and still interact with Ras (Zhao and Vogt 2008), and would therefore be expected to undergo normal ligand-stimulated translocation to cell membranes. Nonetheless, these mutations have potent transforming activity. These data strongly suggest that the relatively small increases in Class IA PI 3-kinase specific activity caused by SH2 domain occupancy are critical for function in vivo.

The effect of Ras binding on Class IA PI 3-kinase activity is somewhat more complex. As discussed above, Ras binding to p110γ causes changes in the catalytic cleft, consistent with direct allosteric regulation of activity (Pacold et al. 2000). However, the original studies on Ras activation only saw increases in PI 3-kinase activity with prenylated Ras, despite the fact that non-prenylated GTP-loaded Ras can still bind to p110α (Rodriguez-Viciana et al. 1996). Thus, Ras is likely to activate by Class I PI 3-kinase by a combination of translocation and activation. This point was directly supported by studies showing that the transforming capacity of overexpressed p110β and δ is abolished by mutation of the Ras-binding site, but rescued by N-terminal myristylation (Denley et al. 2008). Similarly, the H1047R mutant of p110α, whose transforming potential is insensitive to mutation of the Ras binding sites, appears to act by enhancing p110α interactions with cellular membranes (Mandelker et al. 2009; Zhao and Vogt 2008).

10 Unanswered Mechanistic Questions on p85–p110 Interactions

Despite the concerted efforts of numerous laboratories, many very basic questions about p85–p110 interactions remain unanswered. With regard to structural questions, the structure of the nSH2-iSH2 fragment of p85 dimerized with p110α has been solved (Mandelker et al. 2009), but we know virtually nothing about how the rest of p85 (the cSH2 domain, as well as the SH3, proline-rich and BCR homology domains) is organized in space. Hopefully, continued advances using biochemical and biophysical methods will lead to new information on these issues in the near future, and will undoubtedly increase our understanding of how interactions between these domains and upstream activators regulate the catalytic activity of p110.

An even more complex question is that of the specificity of p85–p110 pairing and regulation. Mass spectrometry studies have suggested that p85 and p110 expression levels are matched in multiple cell types and tissues (Geering et al. 2007), although this point has been controversial (Brachmann et al. 2005). However, we know very little about whether there is selectivity for the interaction of distinct p110 isoforms with distinct p85/p55 isoforms, since any one of the p110 ABD domains should be able to bind to all the p85/p50/p55 iSH2 domains. Given that knockout, knock-in and transgenic studies in mice have clearly demonstrated distinct physiological roles for the isoforms of p85 and p110 (reviewed in Fruman 2007; Liu et al. 2009; Vanhaesebroeck et al. 2005), one would think that the pairing of different Class IA regulatory and catalytic subunits would be a regulated process with significant physiological consequences. If so, then we have not even begun to figure out the rules for this sorting process, nor are the mechanisms for selectivity apparent. This question is likely to converge on the broader question of the isoform specificity of PI 3-kinase signaling in vivo, which has been a major focus of recent work in the field (Marone et al. 2008; Rommel et al. 2007; Stuart and Sellers 2009).

A significant caveat with regard to our current understanding of p85–p110 interactions is that nearly all the in vitro experiments have been done with p85α and p110α. For example, it will be very important to analyze mutants such as the acidic helical domain mutants of p110α (e.g., E545K) in the context of p110β and p10δ, to see if they have similar effects on the regulation of these isoforms. This is also true for recently described point mutants of p85α. New biochemical studies on p110β should be particularly interesting, since this isoform appears to have all the p85-related tools in place for regulation by receptor tyrosine kinases, yet somehow is instead activated downstream of GPCRs. Finally, very little biochemical analysis has been done on the shorter splice variants and isoforms of p85, p55α, p50α and p55γ. These variants contain the same nSH2-iSH2-cSH2 organization found in the so-called p85nic construct that has been extensively studied in vitro (Wu et al. 2007), but p55γ and p55α contain homologous 30 amino acid N-terminal extensions that contains a YXXM motif (Dey et al. 1998; Inukai et al. 1996) and has been suggested to associate with tubulin and with the retinoblastoma gene product Rb (Inukai et al. 2000; Xia et al. 2003). The potential role of these additional sequences in the regulation of Class IA dimers is not known. A better understanding of the enzymatic regulation of p110 catalytic subunits by these isoforms will be important in deciphering their differential regulation and physiological functions in vivo.

The biochemical analysis of these large and complex enzymes remains a challenging enterprise. Given the important role of the PI 3-kinases in human physiology, it is to be hoped that an enhanced understanding of how the enzymes work will lead to new ideas about the pharmacological modulation of their activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants GM55692, DK07069, and 1 PO1 CA100324, and grants from American Diabetes Association and the Janey Fund. I thank Dr. Mirvat El-Sibai, Beirut University, for critical reading of the manuscript. I also thank Drs. Mark Girvin, Gary Gerfen, Steve Almo, and George Orr (deceased) at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and Dr. Roger Williams at the MRC, Cambridge, for collaboration and hours of discussion over the past decade. Finally, I thank all my graduate students and postdocs for their scientific contributions to many of the studies cited here.

References

- Ahmed S, Lee J, Wen L-P, Zhao Z, Ho J, Best A, Kozma R, Lim L. Breakpoint Cluster Region gene product-related domain of n-Chimaerin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17642–17648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer JM, Myers MG, Jr, Shoelson SE, Chin DJ, Sun XJ, Miralpeix M, Hu P, Margolis B, Skolnik EY, Schlessinger J et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase is activated by association with IRS-1 during insulin stimulation. EMBO J. 1992;11(9):3469–3479. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader AG, Kang S, Vogt PK. Cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA are oncogenic in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(5):1475–1479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510857103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeton CA, Das P, Waterfield MD, Shepherd PR. The SH3 and BH domains of the p85alpha adapter subunit play a critical role in regulating Class Ia phosphoinositide 3-kinase function. Mol Cell Biol Res Comm. 1999;1:153–157. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.1999.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeton CA, Chance EM, Foukas LC, Shepherd PR. Comparison of the kinetic properties of the lipid- and protein-kinase activities of the p110alpha and p110beta catalytic subunits of class-Ia phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 2):353–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernado P, Garcia de la Torre J, Pons M. Interpretation of 15N NMR relaxation data of globular proteins using hydrodynamic calculations with HYDRONMR. J Biomol NMR. 2002;23(2):139–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1016359412284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokoch GM, Vlahos CJ, Wang Y, Knaus UG, Traynor-Kaplan AE. Rac GTPase interacts specifically with phosphatidylinositol 3- kinase. Biochem J. 1996;315:775–779. doi: 10.1042/bj3150775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyreff B, Rasmussen TL, Jensen HH, Cloutier A, Beaudet L, Roby P, Issinger OG. Expression and purification of PI3 kinase alpha and development of an ATP depletion and an alphascreen PI3 kinase activity assay. J Biomol Screen. 2008;13(10):1035–1040. doi: 10.1177/1087057108326079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker GW, Breeze AL, Downing AK, Panayotou G, Gout I, Waterfield MD, Campbell LD. Structure of an SH2 domain of the p85α subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3 OH-kinase. Nature. 1992;358:684–687. doi: 10.1038/358684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann SM, Ueki K, Engelman JA, Kahn RC, Cantley LC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit deletion and regulatory subunit deletion have opposite effects on insulin sensitivity in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(5):1596–1607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1596-1607.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley LC, Auger KR, Carpenter C, Duckworth B, Graziani A, Kapeller R, Soltoff S. Oncogenes and signal transduction. Cell. 1991;64:231–302. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90639-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CL, Auger KR, Chanudhuri M, Yoakim M, Schaffhausen B, Shoelson S, Cantley LC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase is activated by phosphopeptides that bind to the SH2 domains of the 85-kDa subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(13):9478–9483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JD, Van Aller G, Lehr R, Sinnamon RH, Kirkpatrick RB, Auger KR, Dhanak D, Copeland RA, Gontarek RR, Tummino PJ, Luo L. Effects of oncogenic p110alpha subunit mutations on the lipid kinase activity of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem J. 2008;409(2):519–524. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CGART. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain MD, Berry TR, Pastor MC, Anderson DH. The p85alpha subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase binds to and stimulates the GTPase activity of Rab proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):48607–48614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TO, Rodeck U, Chan AM, Kimmelman AC, Rittenhouse SE, Panayotou G, Tsichlis PN. Small GTPases and tyrosine kinases coregulate a molecular switch in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulatory subunit. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaussade C, Cho K, Mawson C, Rewcastle GW, Shepherd PR. Functional differences between two classes of oncogenic mutation in the PIK3CA gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381(4):577–581. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforidis S, Miaczynska M, Ashman K, Wilm M, Zhao L, Yip S-C, Waterfield MD, Backer JM, Zerial M. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinases are Rab5 effectors. Nature Cell Biology. 1999;1:249–252. doi: 10.1038/12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciraolo E, Iezzi M, Marone R, Marengo S, Curcio C, Costa C, Azzolino O, Gonella C, Rubinetto C, Wu H, Dastru W, Martin EL, Silengo L, Altruda F, Turco E, Lanzetti L, Musiani P, Ruckle T, Rommel C, Backer JM, Forni G, Wymann MP, Hirsch E. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110beta activity: key role in metabolism and mammary gland cancer but not development. Sci Signal. 2008;1(36):ra3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas BD, Lu Y, Mao M, Zhang J, LaPushin R, Siminovitch K, Mills GB. Tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 relieves its inhibitory activity on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(29):27455–27461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czupalla C, Culo M, Muller EC, Brock C, Reusch HP, Spicher K, Krause E, Nurnberg B. Identification and characterization of the autophosphorylation sites of phosphoinositide 3-kinase isoforms beta and gamma. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(13):11536–11545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denley A, Kang S, Karst U, Vogt PK. Oncogenic signaling of class I PI3K isoforms. Oncogene. 2008;27(18):2561–2574. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deora AA, Win T, Vanhaesebroeck B, Lander HM. A redox-triggered ras-effector interaction. Recruitment of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase to Ras by redox stress. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(45):29923–29928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey BR, Furlanetto RW, Nissley SP. Cloning of human p55 gamma, a regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, by a yeast two-hybrid library screen with the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. Gene. 1998;209(1′2):175–183. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhand R, Hara K, Hiles I, Bax B, Gout I, Panayotou G, Fry MJ, Yonezawa K, Kasuga M, Waterfield MD. PI 3-kinase: Structural and functional analysis of intersubunit interactions. EMBO J. 1994a;13:511–521. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhand R, Hiles I, Panayotou G, Roche S, Fry MJ, Gout I, Totty NF, Truong O, Vicendo P, Yonezawa K, Kasuga M, Courtneidge SA, Waterfield MD. PI 3-kinase is a dual specificity enzyme: Autoregulation by an intrinsic protein-serine kinase activity. EMBO J. 1994b;13:522–533. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann D, Brill S, Garrett MD, Totty N, Hsuan J, Monfries C, Hall C, Lim L, Hall A. Bcr encodes a GTPase-activating protein for p21-rac. Nature. 1991;351:400–402. doi: 10.1038/351400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(8):606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo JA, Navankasattusas S, Kavanaugh WM, Milfay D, Fried VA, Williams LT. cDNA cloning of a novel 85 kd protein that has SH2 domains and regulates binding of PI3-kinase to the PDGF beta-receptor. Cell. 1991;65(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90409-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantl WJ, Escobedo JA, Martin GA, Turck CW, del Rosario M, McCormick F, Williams LT. Distinct Phosphotyrosines on a Growth Factor Receptor Bind to Specific Molecules that Mediate Different Signalling Pathways. Cell. 1992;69:413–423. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90444-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow NA, Muhandiram R, Singer AU, Pascal SM, Kay CM, Gish G, Shoelson SE, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1994;33(19):5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foukas LC, Beeton CA, Jensen J, Phillips WA, Shepherd PR. Regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase by its intrinsic serine kinase activity in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(3):966–975. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.966-975.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foukas LC, Claret M, Pearce W, Okkenhaug K, Meek S, Peskett E, Sancho S, Smith AJ, Withers DJ, Vanhaesebroeck B. Critical role for the p110alpha phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase in growth and metabolic regulation. Nature. 2006;441(7091):366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature04694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman DA. The role of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase in T-cell function and autoimmunity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 2):177–180. doi: 10.1042/BST0350177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman DA, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Pollard DA, Yballe CM, Brazil D, Bronson RT, Kahn CR, Cantley LC. Hypoglycaemia, liver necrosis and perinatal death in mice lacking all isoforms of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85 alpha. Nat Genet. 2000;26(3):379–382. doi: 10.1038/81715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z, Aronoff-Spencer E, Backer JM, Gerfen GJ. The structure of the inter-SH2 domain of class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase determined by site-directed spin labeling EPR and homology modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(6):3275–3280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535975100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z, Aronoff-Spencer E, Wu H, Gerfen GJ, Backer JM. The iSH2 domain of PI 3-kinase is a rigid tether for p110 and not a conformational switch. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;432(2):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fushman D, Xu R, Cowburn D. Direct determination of changes of interdomain orientation on ligation: use of the orientational dependence of 15N NMR relaxation in Abl SH(32) Biochemistry (Mosc) 1999;38(32):10225–10230. doi: 10.1021/bi990897g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geering B, Cutillas PR, Nock G, Gharbi SI, Vanhaesebroeck B. Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinases are obligate p85-p110 heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7809–7814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700373104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout I, Dhand R, Panayotou G, Fry MJ, Hiles I, Otsu M, Waterfield MD. Expression and characterization of the p85 subunit of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex and a related p85 beta protein by using the baculovirus expression system. Biochem J. 1992;288(Pt 2):395–405. doi: 10.1042/bj2880395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillermet-Guibert J, Bjorklof K, Salpekar A, Gonella C, Ramadani F, Bilancio A, Meek S, Smith AJ, Okkenhaug K, Vanhaesebroeck B. The p110beta isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signals downstream of G protein-coupled receptors and is functionally redundant with p110gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(24):8292–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707761105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinebault C, Payrastre B, Racaud-Sultan C, Mazarguil H, Breton M, Mauco G, Plantavid M, Chap H. Integrin-dependent translocation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase to the cytoskeleton of thrombin-activated platelets involves specific interactions of p85 alpha with actin filaments and focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol. 1995;129(3):831–842. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther UL, Liu YX, Sanford D, Bachovchin WW, Schaffhausen B. NMR analysis of interactions of a phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase SH2 domain with phosphotyrosine peptides reveals interdependence of major binding sites. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15570–15581. doi: 10.1021/bi961783x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Ramjaun AR, Haiko P, Wang Y, Warne PH, Nicke B, Nye E, Stamp G, Alitalo K, Downward J. Binding of ras to phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110alpha is required for ras-driven tumorigenesis in mice. Cell. 2007;129(5):957–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gymnopoulos M, Elsliger MA, Vogt PK. Rare cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA show gain of function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(13):5569–5574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701005104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale BG, Batty IH, Downes CP, Randall RE. Binding of influenza A virus NS1 protein to the inter-SH2 domain of p85 suggests a novel mechanism for phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(3):1372–1380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JJ, Andrews G, Contillo L, Lamphere L, Gardner J, Lienhard GE, Gibbs EM. Potent activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase by simple phosphotyrosine peptides derived from insulin receptor substrate 1 containing two YMXM motifs for binding SH2 domains. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9376–9381. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiles ID, Otsu M, Volinia S, Fry MJ, Gout I, Dhand R, Panayotou G, Ruiz-Larrea F, Thompson A, Totty NF, Hsuan JJ, Courtneidge SA, Parker PJ, Waterfield MD. Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase: Structure and Expression of the 110 kd Catalytic Subunit. Cell. 1992;70:419–429. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90166-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoedemaeker FJ, Siegal G, Roe SM, Driscoll PC, Abrahams JP. Crystal structure of the C-terminal SH2 domain of the p85alpha regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase: an SH2 domain mimicking its own substrate. J Mol Biol. 1999;292(4):763–770. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt KH, Olson AL, Moye-Rowley WS, Pessin JE. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation is mediated by high-affinity interactions between distinct domains within the p110 and p85. subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:42–49. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn S, Bergholz U, Jucker M, McCubrey JA, Trumper L, Stocking C, Basecke J. Mutations in the catalytic subunit of class IA PI3K confer leukemogenic potential to hemato-poietic cells. Oncogene. 2008;27(29):4096–4106. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P, Schlessinger J. Direct association of p110 beta phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with p85 is mediated by an N-terminal fragment of p110 beta. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(4):2577–2583. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P, Mondino A, Skolnik EY, Schlessinger J. Cloning of a novel, ubiquitously expressed human phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and identification of its binding site on p85. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7677–7688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Klippel A, Muslin AJ, Fantl WJ, Williams LT. Ras-dependent induction of cellular responses by constitutively active phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. Science. 1995;268(5207):100–102. doi: 10.1126/science.7701328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CH, Mandelker D, Schmidt-Kittler O, Samuels Y, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Gabelli SB, Amzel LM. The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007;318(5857):1744–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikenoue T, Kanai F, Hikiba Y, Obata T, Tanaka Y, Imamura J, Ohta M, Jazag A, Guleng B, Tateishi K, Asaoka Y, Matsumura M, Kawabe T, Omata M. Functional analysis of PIK3CA gene mutations in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(11):4562–4567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Clemmons DR. Roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration and deoxyriboncleic acid synthesis by insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocrinology. 1999;140(9):4228–4235. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.6980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inukai K, Anai M, Van Breda E, Hosaka T, Katagiri H, Funaki M, Fukushima Y, Ogihara T, Yazaki Y, Kikuchi YO, Asano T. A novel 55-kDa regulatory subunit for phosphatidy-linositol 3-kinase structurally similar to p55PIK Is generated by alternative splicing of the p85alpha gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(10):5317–5320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inukai K, Funaki M, Nawano M, Katagiri H, Ogihara T, Anai M, Onishi Y, Sakoda H, Ono H, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Oka Y, Asano T. The N-terminal 34 residues of the 55 kDa regulatory subunits of phosphoinositide 3-kinase interact with tubulin. Biochem J. 2000;346 (Pt 2:483–489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isakoff SJ, Engelman JA, Irie HY, Luo J, Brachmann SM, Pearline RV, Cantley LC, Brugge JS. Breast cancer-associated PIK3CA mutations are oncogenic in mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(23):10992–11000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal BS, Janakiraman V, Kljavin NM, Chaudhari S, Stern HM, Wang W, Kan Z, Dbouk HA, Peters BA, Waring P, Dela Vega T, Kenski DM, Bowman K, Lorenzo M, Wu J, Modrusan Z, Stinson J, Eby M, Yue P, Kaminker J, de Sauvage FJ, Backer JM, Seshagiri S. Somatic mutations in p85α promote tumorigenesis through class IA PI3K activation. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(6):463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S, Liu Z, Zhang S, Liu P, Zhang L, Lee SH, Zhang J, Signoretti S, Loda M, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;454(7205):776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature07091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez C, Jones DR, Rodríguez-Viciana P, Gonzalez-García A, Leonardo E, Wennström S, Von Kobbe C, Toran JL, Borlado LR, Calvo V, Copin SG, Albar JP, Gaspar ML, Diez E, Marcos MAR, Downward J, Martinez C, Mérida I, Carrera AC. Identification and characterization of a new oncogene derived from the regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. EMBO J. 1998;17:743–753. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez C, Hernandez C, Pimentel B, Carrera AC. The p85 regulatory subunit controls sequential activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase by Tyr kinases and Ras. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(44):41556–41562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker M, Sudel K, Horn S, Sickel M, Wegner W, Fiedler W, Feldman RA. Expression of a mutated form of the p85alpha regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in a Hodgkin’s lymphoma-derived cell line (CO) Leukemia. 2002;16(5):894–901. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Bader AG, Vogt PK. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mutations identified in human cancer are oncogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(3):802–807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408864102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]