Abstract.

Introduction

The aim of the study was to evaluate the correlation between the presence of anti-C. trachomatis (C.t.) antibodies in serum and expressed prostatic secretions (EPS) and the concentration of citric acid in patients with chronic prostatitis.

Materials and Methods

The study involved 34 men with chronic prostatitis. The leukocyte count, presence of anti-C.t. antibodies (IgA, IgG), and citric acid concentration were determined in the EPS. The serum was examined for IgM, IgA, and IgG anti-C.t. antibodies. Specific antibodies were determined using the EIA method. The concentration of citric acid was measured using the ultraviolet method.

Results

Inflammation of the prostate (≥10 PMN) was found in 61.8% of the patients. A reduction in citric acid concentration in the EPS was detected in 58.8% of the men. Specific serum antibodies were detected in 58.8% of the patients, including 23.5% with IgM, 32.4% with IgA, and 44.1% with IgG. In all patients, serum IgM and IgA antibody titers were low, while those of IgG antibodies were strongly positive in 46.7% of the patients. Anti-C.t. antibodies in the EPS were detected in 44.1% of the patients, including 32.4% with IgA and 35.3% with IgG. In contrast to serum, the titers of IgG antibodies in the EPS were low in all the patients, while those of IgA were strongly positive in 54.5% of cases. In patients with positive serological outcomes, 85% had reduced concentrations of citric acid.

Conclusions

The occurrence of anti-C.t. antibodies is usually accompanied by a decrease in the concentration of citric acid in the prostatic secretion.

Keywords. Chlamydia trachomatis, citric acid, prostate gland, expressed prostatic secretions, antichlamydial antibodies

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis) is a major sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen [1]. Since chlamydial infections are usually asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic, they are difficult to diagnose and may thus lead to serious sequels. One of the complications of C. trachomatis infection in men is chronic prostatitis [15, 22, 24]. The concentration of citric acid, which is produced and stored in the prostate in great amounts, can be regarded as an indicator of the normal functioning of the prostate [2, 6]. When the function is impaired, e.g. due to prostatitis, the concentration of citric acid is reduced [2, 7].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the correlation between the presence of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the serum and prostatic secretion and the concentration of citric acid in patients with chronic prostatitis.

Materials and Methods

The study involved 34 men aged 18–65 years (mean: 38 years) with chronic prostatitis referred to the Center for Sexually Transmitted Disease Research and Diagnostics in Białystok by urological consulting units. These patients belonged to group III according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) prostatitis classifipain syndrome [15]. None of the patients had been treated with antibiotics for at least three months before the study.

Expressed prostatic secretions (EPS) and blood serum were used as the material for analysis. The polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) count, the presence of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies (IgA and IgG), and citric acid concentration were determined in the prostatic secretion. The serum was examined for IgM, IgA, and IgG class anti-C. trachomatis antibodies.

A drop of EPS was used to make a direct preparation on a glass slide. After fixation and staining by means of Gram's method, leukocytes were counted. Inflammation of the prostate was diagnosed when the PMN count was >-10 in the visual field under a light microscope with a magnification of ×1000.

The anti-C. trachomatis antibodies were determined using the immunoenzymatic method. Specific IgG antibodies were identified in the serum by means of Chlamydia IgG EIA (Labsystem, Finland) and serum IgM+IgA and IgG+IgA in the EPS with Chlamydia rELISA (Medac, Germany). In the tests performed using the Labsystem kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions a value of ≥20 enzyme immunoassay unit (EIU) was considered positive (<10 EIU: negative, 10–19 EIU: equivocal, 20–59 EIU: weakly positive, 60–110 EIU: positive, >110 EIU: strongly positive). With the Medac kit, titers equal to or greater than 1:100 (IgG antibodies) and 1:50 (IgM and IgA antibodies) were treated as positive.

The concentration of citric acid was determined at the Department of Medical Biochemistry, Medical University of Bia3ystok, using the ultraviolet method (TC Citric Acid, Boehringer, Germany) [23]. A concentration of 18.84±0.72 mg/ml (18.12–19.59 mg/ml) was treated as normal [5].

This study was approved by the University Ethics Committee.

Results

Inflammation of the prostate was found in 21/34 (61.8%) patients. A reduction in citric acid concentration in the prostatic secretion was detected in 20/34 (58.8%) men. In most patients (17/20, 85%), the reduced citric acid concentration was accompanied by an elevated PMN count in the EPS (>-10/vision field).

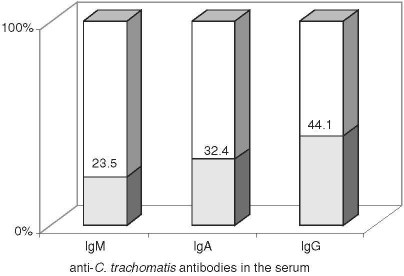

Specific serum antibodies were detected in 20/34 (58.8%) patients, including IgM in 8/34 (23.5%), IgA in 11/34 (32.4%), and IgG in 15/34 (44.1%; Fig. 1). All the patients showed low titers of IgM and IgA antibodies in the serum and 7/15 (46.7%) patients had strongly positive IgG antibodies. In 11/15 (73.3%) patients, the specific IgG antibodies in the serum occurred together with IgM and/or IgA antibodies, and were found isolated in the remaining 4/15 (26.7%) cases. Table 1 presents a list of positive serological outcomes according to the immunoglobulin classes. The synergistic occurrence of IgG and IgA was the most common (35%), the isolated occurrence of IgG antibodies was less common (20%), and of IgA the least common (5%).

Fig. 1.

The rate of detection of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the serum in chronic prostatitis patients.

Table 1.

Co-occurrence of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies according to immunoglobulin class in a group of 20 patients with serum-positive serological outcomes

| Class of immunoglobulin anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in serum | Patients with serum-positive serological outcomes (N=20) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| IgM | 2 | 10 |

| IgA | 1 | 5 |

| IgG | 4 | 20 |

| IgG+IgM | 2 | 10 |

| IgG+IgA | 7 | 35 |

| IgM+IgA | 2 | 10 |

| IgG+IgM+IgA | 2 | 10 |

| Total | 20 | 100 |

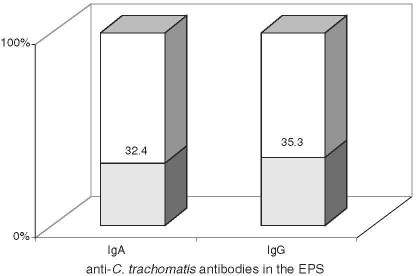

The anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the EPS were detected in 15/34 (44.1%) patients, including 11/34 (32.4%) with IgA and 12/34 (35.3%) with IgG (Fig. 2). In contrast to serum, the titers of IgG antibodies in the EPS were low in all the patients, while those of IgA were strongly positive in 6/11 (54.5%) patients. Table 2 presents the serum antibodies of the respective classes in the EPS. The co-occurrence of IgA and IgG (53.3%) was the most frequent, isolated IgG antibodies were less common (26.7%), and isolated class IgA the least common (20%).

Fig. 2.

The rate of detection of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the EPS in chronic prostatitis.

Table 2.

Co-occurrence of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies according to immunoglobulin class in a group of 15 patients with EPS-positive serological outcomes

| Class of immunoglobulin anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the EPS | Patients with EPS-positive serological outcomes (N=15) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| IgA | 3 | 20 |

| IgG | 4 | 26.7 |

| IgG+IgA | 8 | 53.3 |

| Total | 15 | 100 |

In the group of 20 patients with positive serum and/or EPS outcomes, 17 (85%) had reduced concentrations of citric acid (Table 3). In the majority of patients with reduced citric acid concentration in the EPS (16/17, 94.1%), anti-C. trachomatis antibodies were present both in the serum and EPS. The greatest decline in the concentration of citric acid was observed in men showing remarkably high titers of IgA antibodies in the EPS and/or IgG in the serum.

Table 3.

Correlation of occurrence of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in serum or/and EPS with citric acid concentration in the prostatic secretion

| Concentration of citric acid in EPS | Patients with positive serological outcomes (N=20) | Total (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| only in EPS n (%) | only in serum n (%) | in EPS and in serum n (%) | ||

| Decreased | 0 | 1 (5) | 16 (80) | 17 (85) |

| No changes | 0 | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (15) |

| Total | 0 | 4 (20) | 16 (80) | 20 (100) |

Discussion

Prostatitis, a major sequel of C. trachomatis urethritis in men, is usually chronic and oligosymptomatic [17]. The bacteriological diagnostics of prostatitis is very difficult, mainly due to the poor availability of adequate material and the difficult choice of a proper method [21]. Fundamental methods in diagnosing chlamydial infections are direct methods that detect bacterial antigens (DIF, i.e. the direct immunfluorescence test, and EIA), genetic material (PCR, i.e. polymerase chain reaction, LCR, i.e. ligase chain reaction), or, currently rarely performed, culture methods. The role of serodiagnostics using both serum and prostatic secretion has been emphasized in literature, especially because of the non-invasive nature of the method and the easy availability of the material [18]. There are only a few studies concerning the problem of chlamydial prostatitis combined with determining citric acid concentration.

In our study, serum IgG antibodies were the most frequently detected (44.1%), IgA antibodies were less, and IgM the least common (32.4% and 23.5%, respectively). In all cases the titers of IgA and IgM antibodies were low, while those of IgG were high in nearly half of the patients (46.7%). Similar or higher values of IgG antibodies were noted by Weidner et al. [20] (40.5%) and Peeters et al. [16] (49%), but lower were reported by Kojima et al. [9] (7.5%) and Miyata et al. [14] (29%). High titers of specific IgG antibodies as well as the presence of IgA antibodies in the serum provide evidence for an active, Chlamydia-induced pathological process. The role of IgM antibodies in the diagnostics of chronic prostatitis is slight, as they can be detected only in the very early phase of infection and are thus rarely found in men with chronic prostatitis [4, 12].

We found specific IgG antibodies in the prostatic secretion in 35.3% of the men and IgA in 32.4%. Contrary to the serum, the values of IgA antibodies in the EPS were considerably higher than the titers of IgG antibodies. In all the patients, the presence of specific antibodies in the EPS was accompanied by anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the serum and elevated EPS leukocyte count. Similar results concerning IgA antibodies were reported by Japanese authors, who found them in the prostatic secretion in 31.5% [13] and 29% [10] of men. High titers of IgA antibodies and increased PMN counts detected in the EPS indicate stimulation of the local immunological response by resident microorganisms. Tsunekawa et al. [18, 19] also observed high titers of IgA and low titers of IgG in the EPS compared with serum. Ludwig et al. [11] considered the determination of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in serum unserviceable in diagnosing chlamydial infection, while the role of antibodies in semen, especially the IgA class, is still unclear and needs further investigation. The authors revealed in their study significant correlation only between seminal plasma antibodies against C. trachomatis and positive PCR results in the ejaculate. In our study, the level of IgA antibodies in the EPS was particularly high, in contrast to the serum level.

The role of antichlamydial antibodies in C. trachomatis infection is still controversial. However, it is still believed that antibody marking may be important in detecting the spread of chronic urogenital tract infections on the ascending path from the urethra or cervix and its remote complications, such as epididymitis, prostatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or infertility.

In most patients (85%) with specific antibodies detected in the serum or/and EPS there was a simultaneous decrease in the concentration of citric acid in the prostatic secretion. The prostate is the major site of production and the largest reservoir of citric acid in the organism [3, 6]. The level of citric acid decreases in inflammatory conditions of the prostate and in other diseases that impair the functioning of the gland [2, 8]. A reduced concentration of citric acid in patients with detected infection of C. trachomatis suggests the existence of prostatitis induced by Chlamydia. In an earlier study we conducted research in the same group of patients evaluating the relationship between chlamydial prostatitis detected by means of direct tests (DIF, PCR) and citric acid concentration in the prostate gland [25]. We found that chlamydial infection of the prostate coexisted in all cases with a reduced concentration of citric acid, in most of the cases significantly. No literature reports are available on the relationship between the detection of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the serum and/or EPS and the concentration of citric acid in the EPS.

In conclusion, 1) the occurrence of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in the serum and/or EPS in most patients is accompanied by a decrease in the concentration of citric acid in the prostatic secretion, suggesting functional impairment of the gland; 2) serological investigations of the serum and EPS for chlamydial infection can be treated as a supplementary, non-invasive method in the diagnostics of chronic prostatitis.

Acknowledgment

This was supported by grant no. 493978 of the Medical University in Białystok.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003): Chlamydia Prevalence Monitoring Project Annual Report 2002 in Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Surveillance 2002 Suppl., Atlanta, GA, USA.

- 2.Cooper T. G., Weidner W., Nieschlag E. The influence of inflammation of the human genital tract on the secretion of the seminal markers α-glucosidase, glycerophosphocholine, carnitine, fructose and citric acid. J. Androl. 1990;13:329–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1990.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello L. C., Franklin R. B. Concepts of citrate production and secretion by prostate: 1. Metabolic relationships. Prostate. 1991;18:25–46. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990180104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doble A., Thomas B. J., Walker M. M., Harris J. R., Witherow R. O., Taylor-Robinson D. The role of Chlamydia trachomatis in chronic abacterial prostatitis: a study using ultrasound guided biopsy. J. Urol. 1989;141:332–333. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40758-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fair W. R., Cordonnier J. J. The pH of prostatic fluid: a reappraisal and therapeutic implications. J. Urol. 1978;120:695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frick J., Aulitzky W. Physiology of the prostate. Infection. 1991;19(suppl.3):115–118. doi: 10.1007/BF01643679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kammer H., Scheit K. H., Weidner W., Cooper T. G. The evaluation of markers of prostatic function. Urol. Res. 1991;19:343–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00310147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavanagh J. P., Darby C., Costello C. B. The response of seven prostatic fluid components to prostatic disease. Int. J. Androl. 1982;5:487–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1982.tb00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima H., Wang S. P., Kuo C. C., Grayston J. T. Chlamydia trachomatis is a cause of prostatitis. J. Urol. 1988;139:483A. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koroku M., Kumamoto Y., Hirose T. A study on the role of Chlamydia trachomatis in chronic prostatitis — analysis of anti-Chlamydia trachomatis specific IgA in expressed prostate secretion by western-blotting method. J. Jap. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 1995;69:426–437. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.69.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig M., Hausmann G., Scriba M., Zimmermann O., Fischer D., Thiele D., Weidner W. Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies in serum and ejaculate of male patients without acute urethritis. Ann. Urol. 1996;30:139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mardh P. A., Ripa K. T., Colleen S., Treharne J. D., Darougar S. Role of Chlamydia trachomatis in non-acute prostatitis. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 1978;54:330–334. doi: 10.1136/sti.54.5.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruta N. Study of Chlamydia trachomatis in chronic prostatitis. Acta Urol. Jap. 1992;38:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyata Y., Sakai H., Kanetake H., Saito Y. Clinical study of serum antibodies specific to Chlamydia trachomatis in patients with chronic nonbacterial prostatitis and prostatodynia. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1996;42:651–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickel J. C., Nyberg L. M., Hennenfent M. Research guidelines for chronic prostatitis: consensus report from the first national institutes of health international prostatitis collaborative network. Urology. 1999;54:229–233. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peeters M., Polak-Vogelzang A., Debruyne F., Veen J. Abacterial prostatitis: microbical data. In: Brunner H., Krause W., Rothauge C.^.F., Weidner W., editors. Chronic prostatitis. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 1985. pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skerk V., Schonwald S., Krhen I., Markovinovic L., Beus A., Kuzmanovic N. S., Kruzic V., Vince A. Aetiology of chronic prostatitis. Int. J. Antimicrobial Agents. 2002;19:471–474. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsunekawa T., Kumamoto Y. A study of IgA, IgG titers for Chlamydia trachomatis in serum and prostatic secretion of chronic prostatitis. J. Jap. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 1989;63:130–137. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.63.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsunekawa T., Kumamoto Y., Hayashi K., Satoh T. A study of secretory IgA antibody titers for Chlamydia trachomatis in prostatic secretion of chronic prostatitis. J. Jap. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 1991;65:262–266. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.65.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weidner W., Arens M., Krauss H., Schiefer H. G., Ebner H. Chlamydia trachomatis in “abacterial” prostatitis: microbiological, cytological and serological studies. Urol. Int. 1983;38:146–149. doi: 10.1159/000280879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weidner W., Diemer T., Huwe P., Rainer H., Ludwig M. The role of Chlamydia trachomatis in prostatitis. Int. J. Antimicrobial Agents. 2002;19:466–470. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weidner W., Schiefer H. G., Krauss H. Role of Chlamydia trachomatis and mycoplasmas in chronic prostatitis. Urol. Int. 1988;43:167–173. doi: 10.1159/000281331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. 3rd ed. Cambridge: The Press Syndicate University of Cambridge; 1992. pp. 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zdrodowska-Stefanow B., Ostaszewska I. Chlamydia trachomatis — infection in humans. Wrocław: Volumed; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zdrodowska-Stefanow B., Ostaszewska-Puchalska I., Badyda J., Galewska Z. The effect of Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the prostate gland on the concentration of citric acid. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2006;54:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s00005-006-0009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]