Abstract

Objective

To determine association of anemia and RBC transfusions with NEC in preterm infants.

Study Design

111 preterm infants with NEC ≥ Stage 2a were compared with 222 matched controls. 28 clinical variables, including hematocrit and RBC transfusions were recorded. Propensity scores and multivariate logistic regression models were created to examine effects on the risk of NEC.

Results

Controlling for other factors, lower hematocrit was associated with increased odds of NEC [OR 1.10, p =0.01]. RBC transfusion has a temporal relationship with NEC onset. Transfusion within 24h (OR=7.60, p=0.001) and 48h (OR=5.55, p=0.001) has a higher odds of developing NEC but this association is not significant by 96h (OR= 2.13, p =0.07), post transfusion

Conclusions

Anemia may increase the risk of developing NEC in preterm infants. RBC transfusions are temporally related to NEC. Prospective studies are needed to better evaluate the potential influence of transfusions on the development of NEC.

Keywords: transfusion related gut injury, hematocrit

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a known complication of prematurity with high morbidity and mortality. About 7–13% of all very low birth weight (VLBW) infants admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU) develop NEC, with mortality ranging from 10–44%(1–3).

A variety of factors have been associated with the development of NEC including early initiation of enteral feedings, use of post-natal steroids, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and indomethacin use, breast milk versus formula feeds, and presence of umbilical catheters. (4) All preterm infants develop physiologic anemia of prematurity and this is aggravated by iatrogenic blood loss, resulting in frequent red blood cell transfusions. It has been proposed that anemia leads to compromise of the mesenteric blood flow causing intestinal hypoxia and mucosal injury. (5–9) Transfusion related reperfusion injury endured by a hypoxemic gut has also been postulated to predispose anemic preterm infants to develop NEC. (10–15)

We conducted a retrospective case-control study for the purposes of characterizing the association of NEC with anemia of prematurity and red blood cell transfusions in preterm infants.

MATERIALS/SUBJECTS and METHODS

This is a retrospective case- control study of preterm infants, ≤ 32 weeks gestational age, diagnosed with NEC Stage 2a or greater admitted to Level III NICUs at Baystate Children’s Hospital and Tufts Medical Center between Jan, 2000 and Dec, 2008. All cases of NEC were identified by review of administrative codes during the study period. Each case had 2 gestational age (GA ± 1 week) and birth date (± 2 weeks) matched controls admitted to NICU during the study period. Infants with known chromosomal anomalies, congenital heart disease and spontaneous intestinal perforation were excluded from both cases and controls.

Maternal and infant characteristics known to be associated with NEC were recorded. Maternal characteristics included pregnancy induced hypertension, chorioamnionitis as defined by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, administration of antenatal steroids prior to delivery, premature prolonged rupture of membranes (PPROM) and abnormal end- diastolic placental flow (AEDF) as documented by prenatal ultrasound. Infant data included birth date; GA documented as completed weeks of gestation, confirmed by the first trimester ultrasound or maternal last menstrual period (LMP); birth weight; gender; mode of delivery and Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes. Case charts were reviewed to confirm a diagnosis of NEC Stage 2a or greater as classified by modified Bell staging criteria. (16) NEC was classified as early NEC if onset was within first 21 days of birth; all other cases were classified as late NEC. Anemia during the neonatal period (< 28 days of life) was defined as a central venous hematocrit < 39%. Based on the College of American Pathologists Neonatal Red Blood Cell Transfusion Guidelines, anemia was classified as mild if Hct was ≥35% but <39%, moderate if Hct was ≥25% but < 35% and severe if Hct was <25% (16, 17). Other infant variables included presence of central lines (umbilical arterial, umbilical venous and percutaneous intravenous central catheter [PICC] lines); hypotension defined as blood pressure >2 standard deviations below normal for gestational age (18) and the use of volume expander or vasopressor therapy; PDA and need for indomethacin therapy or surgical ligation; positive blood culture; breast milk or formula feedings; achievement of full feeds prior to onset; use of additives (human milk fortifier, powdered formula, oral sodium and potassium supplements), iron therapy, erythropoietin therapy, antacid therapy and use of post-natal steroids for chronic lung disease. Information about the lowest hematocrit (Hct), total number of transfusions administered during the NICU stay, and RBC transfusion for cases and controls 24 hours, 48 hours and 96 hours prior to day of diagnosis for the case were recorded. For the controls the timing for 24hr, 48hr and 96hr was determined using the day of diagnosis in the index case and then using this chronological age as the reference point. We used 24hr and 48hr as reported in literatures as well as 96 hours as the cutoffs based upon the assumption that this would be the critical time period for any impact from low hematocrit and/or transfusions.

We also determined clinical outcomes prior to hospital discharge, including short gut syndrome, cholestasis, chronic lung disease (CLD), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), intaventricular hemorrhage (IVH), length of stay, death and discharge home as markers of the impact of NEC on neonatal outcomes. CLD was identified from the Vermont Oxford Network database based algorithm, which has been tested with actual hospital data and found to be more accurate than the oxygen at 36 weeks measure. (19). IVH was graded as per Papile’s classification. (20). ROP was diagnosed based on the ophthalmologic exam and classified using International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity (ICROP) criteria. (21)

Baystate Medical Center and Tufts Medical Center Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained prior to conducting the study.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were examined with paired t-tests and categorical variables were tested with McNemar’s test. Propensity scores were generated for RBC transfusion and HCT, and used in subsequent analyses as covariates [see Appendix 1 for a description of the development of the propensity scores].(22) The purpose of propensity scores was to reduce the number of covariates in the models, while reducing bias due to confounding effects (23). Multiple conditional logistic regression models were then created using the variables that were significant at a p-value <0.05. Separate models were created for NEC and hematocrit; NEC and RBC transfusions and NEC with four levels of anemia (normal plus 3 levels of increasing severity). Combined models were created to assess Hct and RBC transfusion and any interaction between them. Subgroup analyses were also performed for early and late NEC.

RESULTS

A total of 333 infants were included in the study- 111 cases and 222 matched controls. The incidence of NEC in all VLBW infants over the study period ranged from 1.7% to 6.6%, with annual variations. The NEC cases and controls had similar mean GA (cases 26.9 ±2.5 w, controls 27.2± 2.3 w; p=0.21) and birth weight (cases 969 ±335 g; controls 1026± 308 g, p=0.14). All the variables in Table 1, except total number of transfusions, were collected prior to the onset of NEC in the index case. The characteristics reaching significance in univariate analysis were AEDF, hypotension with use of volume expanders and vasopressors; PDA, indomethacin use and surgical ligation; presence of central line; positive blood culture; achievement of full enteral feeds; breast milk feeds and use of additives; antacid and iron therapy; total number of transfusions during NICU stay; lowest hematocrit; transfusion within 24hr, 48hr and 96hr of onset in the case (Table 1). In the univariate analysis for all cases of NEC, cases had lower Hct and were more likely to be transfused within 24, 48 and 96 hrs of NEC onset than controls (Table 2).

Table 1.

Maternal and Neonatal clinical characteristics of the cases and controls

| Characteristic | NEC Cases (n = 111) | NEC Controls (n= 222) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gestational age in wks (mean, sd) | 26.9 ± 2.5 | 27.3 ± 2.3 | 0.21 |

| Birth weight in gms (mean, sd) | 969.7 ± 309.0 | 1023.0 ± 338.3 | 0.16 |

| Female | 44 (39.6) | 110 (49.6) | 0.08 |

| Vaginal delivery | 47 (42.3) | 72 (32.4) | 0.07 |

| APGAR 5 min (median, IQR) | 7 (6,9) | 8 (6,9) | 0.46 |

| Maternal Characteristics | |||

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | 21 (18.9) | 35 (15.8) | 0.47 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 17 (15.3) | 28 (13.1) | 0.58 |

| Antenatal steroids | 82 (73.9) | 175 (78.8) | 0.31 |

| Abnormal end-diastolic flow | 29 (26.1) | 96 (43.2) | 0.002 |

| Infant Characteristics | |||

| Hypotension | 52 (46.9) | 60 (27.0) | < 0.001 |

| Volume | 48 (43.2) | 52 (23.4) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressors | 37 (33.3) | 36 (16.2) | < 0.001 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 64 (57.7) | 76 (34.2) | < 0.001 |

| Indomethacin | 52 (46.0) | 77 (34.7) | 0.04 |

| Ligation | 16 (14.4) | 16 (7.2) | 0.03 |

| Central Venous Line | 108 (97.3) | 171 (77.0) | < 0.001 |

| Positive Blood Culture | 43 (38.7) | 51 (23.0) | 0.002 |

| Feedings | |||

| Any feeds started | 103 (92.8) | 205 (92.3) | 0.88 |

| Full feeds achieved | 52 (46.9) | 143 (64.4) | 0.002 |

| Breast Milk | 93 (83.8) | 166 (74.8) | 0.06 |

| Any additives | 53 (47.8) | 132 (59.5) | 0.04 |

| Formula | 58 (52.3) | 120 (54.1) | 0.75 |

| Antacid therapy | 81 (73.0) | 111 (50.0) | < 0.001 |

| Post-natal Steroids for CLD | 19 (17.1) | 32 (14.4) | 0.52 |

| Iron therapy | 37 (33.3) | 125 (56.3) | < 0.001 |

| Epogen | 24 (21.6) | 51 (23.0) | 0.78 |

| Hematocrit within 96 hrs of onset (mean, sd) | 29.9 ± 5.6 | 33.4 ± 6.9 | < 0.001 |

| Total number of transfusions (median, IQR) | 5 (2,8) | 1 (0,4) | < 0.001 |

| Transfusion within 24h of onset | 36 (32.4) | 15 (6.8) | < 0.001 |

| Transfusion within 48h of onset | 44 (39.6) | 23 (10.4) | < 0.001 |

| Transfusion within 96h of onset | 49 (44.1) | 46 (20.7) | < 0.001 |

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Models for All, Early and Late NEC

| Characteristic | NEC Category | N | Conditional logistic model without covariates | Conditional logistic model with covariates 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | |||

| Hematocrit | All NEC | 111 | 1.12 | 1.05, 1.19 | < 0.001 | 1.10 | 1.02, 1.18 | 0.01 |

| Early NEC | 67 | 1.17 | 1.09, 1.26 | < 0.001 | 1.14 | 1.03, 1.27 | 0.009 | |

| Late NEC | 44 | 1.09 | 1.00, 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.78, 1.15 | 0.59 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Anemia severity | All NEC | 111 | 2.05 | 1.41, 2.96 | < 0.001 | 1.41 | 0.87, 2.29 | 0.16 |

|

| ||||||||

| Early NEC | 67 | 2.44 | 1.53, 3.90 | < 0.001 | 1.73 | 0.94, 3.18 | 0.08 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Late NEC | 44 | 1.36 | 0.72, 2.58 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.10, 1.35 | 0.13 | |

|

| ||||||||

| RBC Transfusion within 24 hrs | All NEC | 111 | 11.70 | 4.55, 30.09 | < 0.001 | 7.60 | 2.19, 26.42 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Early NEC | 67 | 22.13 | 5.23, 93.69 | < 0.001 | 15.49 | 2.20, 109.08 | 0.006 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Late NEC | 44 | 4.67 | 1.21, 18.05 | 0.026 | 2.05 | 0.20, 21.29 | 0.55 | |

|

| ||||||||

| RBC Transfusion within 48 hrs | All NEC | 111 | 7.26 | 3.62, 14.54 | < 0.001 | 5.55 | 1.98, 15.59 | 0.001 |

| Early NEC | 67 | 9.55 | 3.67, 24.86 | < 0.001 | 10.22 | 1.83, 57.15 | 0.008 | |

| Late NEC | 44 | 4.93 | 1.75, 13.89 | 0.003 | 6.39 | 1.00, 40.83 | 0.05 | |

|

| ||||||||

| RBC Transfusion within 96 hrs | All NEC | 111 | 3.63 | 2.04, 6.45 | < 0.001 | 2.13 | 0.95, 4.80 | 0.07 |

| Early NEC | 67 | 4.14 | 1.92, 8.90 | < 0.001 | 3.03 | 0.94, 9.80 | 0.06 | |

| Late NEC | 44 | 3.02 | 1.25, 7.30 | 0.01 | 1.11 | 0.24, 5.11 | 0.89 | |

|

| ||||||||

| RBC Transfusion as an ordinal variable | All NEC | 111 | 2.07 | 1.59, 2.70 | < 0.001 | 1.79 | 1.25, 2.58 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Early NEC | 67 | 2.33 | 1.62, 3.35 | < 0.001 | 2.42 | 1.33, 4.40 | 0.004 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Late NEC | 44 | 1.74 | 1.17, 2.59 | 0.006 | 1.32 | 0.69, 2.53 | 0.40 | |

Conditional logistic regression models adjusted for propensity scores, and PROM, aedf, hypotension, breast feeding, additives, iron supplementation, patent ductus arteriosus, central line, antacid

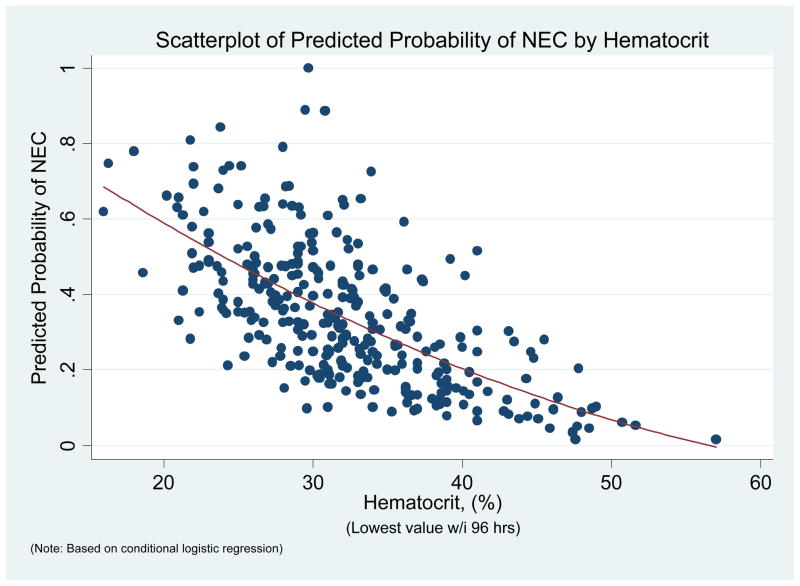

In the multivariate models after controlling for other factors including a propensity-like score for Hct, each one point decrease in the nadir Hct was associated with a 10% increase in the odds of NEC [OR 1.10, (95% CI 1.02 – 1.18), p=0.01]. The risk of NEC increased with lower Hct. (Fig 1). In the combined multivariate model Hct continued to be a significant risk factor after adjusting transfusion within 96h for Hct [OR =1.08, (95% CI: 1.00 – 1.17), p = 0.05]

Figure 1.

Relationship of Hematocrit with probability of NEC

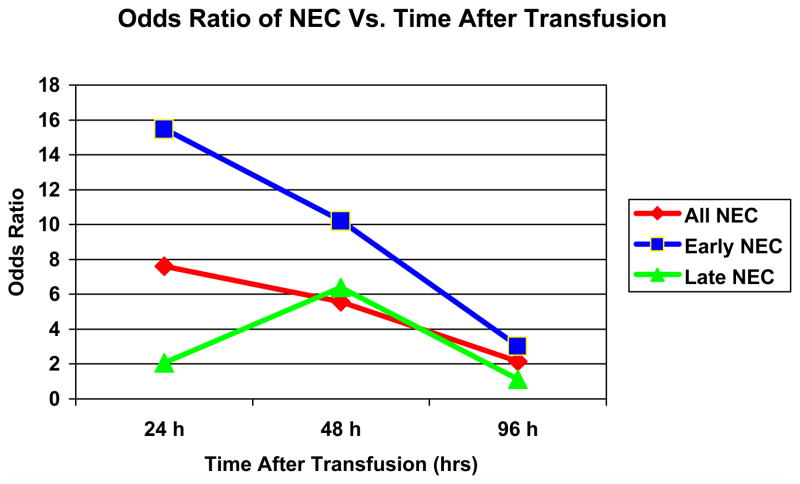

Clinical characteristics of the VLBW infants, excluding Hct, did not discriminate propensity for RBC transfusion. In the multivariate model, adjusting for similar co-variates including propensity for transfusion, the association between transfusion within 96h and NEC was not significant [OR = 2.13, (95% CI: 0.95 –4.80), p= 0.07]. However, to test for a temporal association further analyses were performed for transfusions within 24 and 48hrs. There was a strong association of transfusion within 24hr with NEC [OR=7.60, p =0.001]. This association became less strong for transfusion within 48hr [OR = 5.55, (95% CI: 1.98 – 15.59), p =0.001] and was absent at 96 hr. This temporal relationship was seen for all and early but not late NEC. (Table 2, Figure 2). This association holds true when transfusion is used as an ordinal variable in the multivariate models [OR = 1.79, P = 0.001]. In the combined multivariate models adjusting transfusion for Hct, transfusion within 24hr continues to have highest association [OR= 5.73, P =0.008], followed by 48hr [OR= 5.21, p=0.002] and no association for within 96hr [OR= 1.47, p=0.39] (Table 3). There was no evidence of interaction between Hct and RBC transfusion.

Figure 2.

Plot of Odds ratios for NEC (All, Early and Late) onset and Post Transfusion time interval

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models for All NEC, Early and late NEC, for the combined effects of Hematocrit and Transfusion

| NEC Category | Timing of RBC Transfusion | Conditional logistic model without covariates1 | Conditional logistic model with covariates 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | ||

| All NEC (n=111) | Within 96h

|

1.91 | 1.00, 3.65 | 0.05 | 1.47 | 0.61, 3.54 | 0.39 |

| Within 48h

|

4.95 | 2.37, 10.33 | < 0.001 | 5.21 | 1.86, 14.65 | 0.002 | |

| Within 24h

|

6.60 | 2.48, 17.56 | < 0.001 | 5.73 | 1.59, 20.70 | 0.008 | |

| RBC Transfusion as ordinal | 1.69 | 1.28, 2.25 | < 0.001 | 1.61 | 1.11, 2.35 | 0.01 | |

|

| |||||||

| Early NEC (n= 67) | Within 96h

|

1.89 | 0.79, 4.50 | 0.15 | 2.01 | 0.58, 6.98 | 0.27 |

| Within 48h

|

5.58 | 2.04, 15.27 | 0.001 | 11.20 | 1.86, 67.47 | 0.008 | |

| Within 24h

|

12.87 | 2.39, 56.51 | 0.001 | 15.74 | 2.06, 120.33 | 0.008 | |

| RBC Transfusion as ordinal | 1.85 | 1.26, 2.71 | 0.002 | 2.21 | 1.19, 4.08 | 0.01 | |

|

| |||||||

| Late NEC (n=44) | Within 96h | 2.02 | 0.75, 5.44 | 0.16 | 2.00 | 0.34, 11.76 | 0.44 |

| Within 48h | 3.96 | 1.34, 11.70 | 0.01 | 9.66 | 1.09, 85.39 | 0.04 | |

| Within 24h | 2.59 | 0.61, 1068 | 0.20 | 4.23 | 0.25, 70.76 | 0.32 | |

| RBC Transfusion as ordinal | 1.49 | 0.97, 2.31 | 0.07 | 1.70 | 0.81, 3.56 | 0.16 | |

All models include both RBC transfusion and hematocrit variables

Conditional logistic regression models adjusted for propensity scores, and PROM, aedf, hypotension, breast feeding, additives, iron supplementation, patent ductus arteriosus, central line, antacid

Other factors associated with higher NEC risk in the combined multivariate model included hypotension (OR 2.42, (95% CI: 1.16–5.03), p=0.02) and presence of central lines (OR 7.06, (95% CI: 1.26–39.53), p=0.03) while abnormal end diastolic flow (OR 0.11, (95% CI: 0.03–0.41), p=0.001) and iron therapy (OR 0.34, (95% CI: 0.12–1.00), p=0.05) were associated with lower risk. In contrast to prior studies (6), breast milk feedings did not appear to be protective (OR 2.35, (95% CI: 0.79–7.02), p=0.13).

Associated in-patient morbidities noted for NEC cases and control infants are shown in Table 4. Not surprisingly, the infants post- NEC had poorer outcomes as noted by a higher incidence of cholestasis, short gut syndrome, any IVH, longer length of stay and higher mortality.

Table 4.

Associated in-patient morbidities for the NEC cases and controls.

| Cases (N=111) | Controls (N=222) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short gut syndrome | 12.6% | 0.9% | <0.001 |

| Cholestasis | 49.5% | 9.0% | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 38.7% | 30.5% | 0.13 |

| Retinopathy of Prematurity | 29.9% | 23.3% | 0.2 |

| Any Intraventricular | 48.6% | 32.5% | 0.004 |

| Length of Stay (days) | 75.8 | 62.4 | 0.003 |

| Death | 20.7% | 4.9% | <0.001 |

| Discharge Home/Transfer | 78.9% | 95.5% | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in VLBW infants. Other than prematurity, no single predictive factor has been clearly identified. (24, 25). A multifactorial theory of disease onset is widely accepted with recent interest in the role that anemia and red cell transfusion play in the pathophysiological pathway leading to NEC. We have demonstrated that hematocrit within 96 hours of NEC onset is an important risk factor. Separating the influences of hematocrit and RBC transfusion on NEC is complicated as multiple factors with significant interplay are involved. Severe anemia in VLBW infants is frequently accompanied with other co morbid conditions. Likewise, RBC transfusion is usually associated with other conditions and therapeutic interventions. Despite these complex interactions, present data support the conclusion that low hematocrit within 96 hrs of onset is an important risk factor for development of NEC.

In our study we have attempted to disentangle the influence of hematocrit and RBC transfusion on NEC using a case-control approach. Because multiple factors are likely to be involved in the development of NEC, and because many of these factors are correlated with both anemia severity and the probability of transfusion, which are themselves highly correlated, separating these influences is difficult. Nevertheless, we found that, despite rigorous methods to adjust away confounding—including the use of high-dimensional propensity scores—the effect of lowest hematocrit level on the risk of developing NEC, early NEC in particular, remained statistically and clinically significant.

A potentially causal role of low Hct is certainly possible based on what is known regarding the pathophysiology of anemia and NEC. Anemia may result in decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood to levels less than the demands of the growing tissues, resulting in increased anaerobic metabolism and the production of bi-products such as lactic acid (15). In addition the basal intestinal vascular resistance changes rapidly from the fetal to early neonatal life as this fetal dormant organ becomes functional for enteral nutrition; anemia may impair this normal transition (26, 27). These effects may predispose the preterm gut for endothelial and mucosal apoptosis, a hallmark of NEC. (15). It thus seems plausible that the physiological impact of anemia initiates a cascade of events leading to ischemic- hypoxemic mucosal gut injury predisposing VLBW infants to NEC.

Erythropoietin has been shown to be protective against NEC (33–35). This protective effect may be secondary to prevention of anemia of prematurity. In our study, iron supplementation was associated with a lower risk of NEC, consistent with the hypothesis that prevention or treatment of anemia may be important in preventing or reducing the risk of NEC, although the significance of this finding should be interpreted cautiously given the number of variables included in our model.

The data in early onset NEC patients were similar to the group as a whole, but we did not find an association between Hct and late onset NEC in stable growing preterm infants. While this may be due to inadequate power to detect effects in this subgroup, it could also be that late NEC represents a distinct pathophysiologic entity with its own set of risk factors. Older infants, for example, may tolerate anemia better because infants reach a physiological nadir at this stage. Also, because infants in the control group for late NEC are going through their physiological Hct nadir, the distinction between the cases and the controls becomes less apparent.

Mally et al reported a relationship between late-onset NEC in seventeen stable, growing, premature neonates who were transfused electively for anemia of prematurity (12). In contrast, Bednarek et al reported that there was no significant difference in the incidence of NEC between high versus low transfuser NICUs (32). In addition the PINT trial did not show a difference in the incidence of NEC between the low versus high transfuser groups, however there was a trend towards increased incidence of intestinal perforations (47). There was poorer neurological outcome in the low transfusion group in the Iowa study, but the incidence of NEC was not noted (46, 48). Christensen et al examined factors that may help predict the progression of NEC to Bell Stage III NEC. (31) They found that 38% of their patients had been transfused, but did not have a comparison group and did not correct for Hct.

Currently there are no standard national guidelines for transfusions in NICUs. Protocols may exist in individual units but there is no uniformity (32). Most transfusion protocols are related to respiratory functioning of neonates (16, 17). Recent trends have been towards conservative approach to transfusion by accepting lower hematocrit values. Recently reported concerns that red cell transfusions increase the risk of NEC may have further lowered the hematocrit threshold for transfusion. After correcting for anemia and other clinical characteristics we found a temporal relationship between red blood cell transfusion and NEC onset. RBC transfusions within 24 hr and 48hr were highly associated with NEC however this association disappeared by 96hr after transfusion. We cannot determine from our data the basis for this time course. It is possible that whatever factors are responsible for the increase in NEC 24 and 48 hrs after transfusion have dissipated by 96 hours resulting in a NEC rate similar to that of the anemic population as a whole. It is also possible that non-specific prodromal signs of NEC may have prompted caregivers to transfuse anemic infants.

While the temporal association with RBC transfusion from our data suggests the need for a cautious approach to liberalizing transfusions, the association between anemia and NEC raises the opposing concern--that withholding treatment of severe anemia may increase risk in this population. An experimental trial testing conservative and aggressive transfusion guidelines may be necessary to address this question.

As expected we found that infants with hypotension and central arterial and venous catheters are at higher risk of NEC. Studies have shown that breast milk feedings decrease the risk of NEC (6). In contrast to these studies, we were surprised to find that breast milk feeding did not affect the occurrence of NEC. The reasons for this could be that a high number of infants in both groups were fed breast milk. Additionally, the use of additives may have a role to play. This is supported by a recent study by Sullivan et al who demonstrated that the decreased risk of NEC seen with a human milk-based diet was diminished in infants fed human milk fortified with bovine milk-based products. (36)

We were also surprised to find that our models suggested that infants born to mothers with abnormal placental flow are at a lower risk of NEC, when prior studies have found such infants to be at higher risk (37,38). This may be secondary to conservative feeding management of these infants with a known risk factor.

Even though our study has the limitation of being a retrospective it is the largest study conducted to date to test the associations between NEC, anemia and RBC transfusions. We have tried to minimize the confounding effects of the multiple variables that have known associations with NEC by using propensity score adjustments.

We conclude that anemia is associated with increased risk of developing NEC in preterm infants and this risk increases as anemia worsens. RBC transfusions may also be associated with increased odds of NEC and this association appears to have a temporal relationship, even after controlling for “transfusion propensity” within a multivariable model also including Hct and other important clinical factors. Prospective studies are needed to find the critical level of Hct which may trigger the onset of NEC and also to better evaluate the potential influence of transfusions on the development of NEC.

Acknowledgments

Statement of financial support – Supported in part by Grant Number 3U10HD053119-04S1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by institutional/departmental funds.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest – Authors do not have any conflict of interest disclosures to make

References

- 1.Stoll BJ. Epidemiology of necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin Perinatol. 1994 Jun;21(2):205. doi: 10.1016/S0095-5108(18)30341-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luig M, Lui K. Epidemiology of necrotizing enterocolitis-Part II: Risk and susceptibility of premature infants during the surfactant era: regional study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41(4):174–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holman RC, Stoll BJ, Clarke MJ, Glass RI. The epidemiology of necrotizing enterocolitis infant mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(12):2026–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kafetzis DA, Skevaki C, Costalos C. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: an overview. Curr Opinions in Infectious Disease. 2003 Aug;16(4):349–55. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200308000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy KA, Tyson JE, Chamnanvanakij S. Rapid versus slow rate of advancement of feedings for promoting growth and preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in parenterally fed low-birth-weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001241. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas A, Cole TJ. Breast milk and neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Lancet. 1990 Dec 22–29;336(8730):1519–23. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKeown RE, Marsh TD, Amarnath U, et al. Role of delayed feeding and of feeding increments in necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr. 1992 Nov;121(5 Pt 1):764–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81913-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rayyis SF, Ambalavanan N, Wright L, Carlo WA. Randomized trial of “slow” versus “fast” feed advancements on the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 1999 Mar;134(3):293–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark AR, Carlo WA, Tyson JE, et al. Adverse effects of early dexamethasone in extremely-low-birth-weight infants. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jan 11;344(2):95–101. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101113440203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agwu JC, Narchi H, et al. In a preterm infant, does blood transfusion increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis? Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:102–103. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.051532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Short Andrew, Gallagher Andrew, Ahmed Munir. Necrotizing Enterocolitis following blood transfusion. Electronic letter to the Editor. Arch Dis Child. 2005 Apr 14; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mally P, Golombek SG, Mishra R, La Gamma EF, et al. Association of Necrotizing Enterocolitis with Elective Packed red Blood cell Transfusions in Premature Neonates. Am J Perinatol; Nov. 2006;23 (8):451–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blau J, Calo J, Dozor D, La Gamma E. Transfusion related Acute Gut Injury (TRAGI): Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in VLBW Neonates Following PRBC Transfusion. 2009. Abstract at ESPR. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrady GA, Rettig PJ, Istre GR, et al. An outbreak of necrotizing enterocolitis. Association with transfusion of packed red blood cells. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;126(6):1165–1172. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reber KM, Nankervis CA, Nowicki PT. Newborn intestinal circulation. Physiology and pathophysiology Clin Perinatol. 2002 Mar;29(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(03)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleigman RM, Walsh MC. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: pathogenesis, classification, and spectrum of disease. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1987;17:213. doi: 10.1016/0045-9380(87)90031-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomella TL, Cunnigham MD, Eyal FG, Zenk KE. Handbook of Neonatology. 4. 1999. p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempsey EM, Barrington KJ. Evaluation and Treatment of Hypotension in the Preterm Infant. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaempf JW, Campbell B, Brown A, Bowers K, Gallegos, Goldsmith JP. PCO2 and room air saturation values in premature infants at risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol. 2008;28:48–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birthweights less than 1500 g. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123 (7):991–999. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirano K, Imbens GW. The propensity score with continuous treatments. In: Gelman A, Meng X, editors. Applied Bayesian Modeling and Causal Inference from Incomplete-Data Perspectives. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2004. pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17(19):2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Carpenter JH, Fanaroff AA, Kilpatrick S, LaCorte M, et al. Trends in mortality and morbidity for very low birth weight infants, 1991–1999. Pediatrics. 2002;110:143–151. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, Korones SB, Papile LA, Stoll BJ, et al. Very low birth weight outcomes of the National Institute of Child health and human development neonatal research network, January 1995 through December 1996. NICHD Neonatal Research Network Pediatrics. 2001;107:E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caplan MS, Jilling T. New concepts in necrotizing enterocolitis. Current Opinion Pediatr. 2001;13(2):111–115. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caplan MS, Jilling T. The Pathophysiology of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Neoreviews. 2001;2:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caplan MS, Simon D, Jilling T. The role of PAF, TLR, and the inflammatory response in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005 Aug;14(3):145–51. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alkalay AL, Galvis S, CRNP, et al. Hemodynamic changes in anemic premature infants: are we allowing the hematocrits to fall too low? Pediatrics. 2003;112:838–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alverson DC. The physiologic impact of anemia in the neonate. Clin Perinatology. 1995;22:609–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen RD, et al. Antecedents of Bell stage III necrotizing enterocolitis. J Perinatol. 2010;30:54–57. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bednarek FJ, Weisberger S, Richardson DK, Frantz ID, Shah BL, et al. Variations in blood transfusions among newborn intensive care units. SNAP II Study Group. J Pediatr. 1998;133(5):601–607. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ledbetter DJ, Juul SE. Erythropoietin and the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in infants with very low birth weight. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:178–182. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(00)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohls RK. Erythropoietin to prevent and treat the anemia of prematurity. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1999;11:108–114. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199904000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anemia in the Preterm Infant: Erythropoietin versus Erythrocyte Transfusion – It’s not that simple. Kohorn IV, Ehrenkranz. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, Patel AL, Trawoger R, Lucas A. An Exclusively Human Milk-Based Diet is Associated with a Lower Rate of Necrotizing Enterocolitis than a Diet of Human Milk and Bovine Milk-Based Products. J Peds. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.040. (epub ahead of print, Dec 2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Satar M, Turhan E, Yapicioglu H, Narli N, et al. Cord blood cytokine levels in neonates born to mothers with prolonged premature rupture of membranes and its relationship with morbidity and mortality. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2008 March;19:37–41. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2008.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manogura AC, Turan O, Kush ML, Berg C, Bhide A, et al. Predictors of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm growth- restricted neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(6):638.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boralessa H, Modi N, Cockburn H, et al. RBC T activation and haemolysis in a neonatal intensive care population: implications for transfusion practice. Transfusion. 2002 Nov;42:1428–1434. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucas A, Cole TJ. Breast milk and neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Lancet. 1990 Dec 22–29;336(8730):1519–1523. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stockman JA. Anemia of prematurity. Current concepts in the issue of when to transfuse. Ped Clin N Amer. 1986;33(1):111–128. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ceylan H, Yuncu M, Gurel A, et al. Effects of whole-body hypoxic preconditioning on hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced intestinal injury in newborn rats. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005 Oct;15(5):325–32. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peter CS, Feuerhahn M, Bohnhorst B, Schlaud M, Ziesing S, von der Hardt H, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis: is there a relationship to specific pathogens? Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:67–70. doi: 10.1007/s004310051012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Widness, John A. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Prevention of Neonatal Anemia. NeoReviews. 2000;1 (4):e61–e68. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray NA, Howarth LJ, McCloy MP, Letsky EA, Roberts IA. Platelet transfusion in the management of severe thrombocytopenia in neonatal intensive care unit patients. Transfus Med. 2002;12:35–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2002.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell EF, Strauss RG, Widness JA, Mahoney LT, Mock DM, Seward VJ, et al. Randomized trial of liberal versus restrictive guidelines for red blood cell transfusion in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1685–1691. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirpalani H, Whyte RK, Andersen C, Asztalos EV, Heddle N, Blajchman MA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a restrictive (low) versus liberal (high) transfusion threshold for extremely low birth weight infants, the PINT study. J Pediatr. 2006;149:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bell EF. Transfusion thresholds for preterm infants: how low should we go? J Pediatr. 2006;149(3):287–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]