Abstract

Background

The canine Gram-negative Helicobacter bizzozeronii is one of seven species in Helicobacter heilmannii sensu lato that are detected in 0.17-2.3% of the gastric biopsies of human patients with gastric symptoms. At the present, H. bizzozeronii is the only non-pylori gastric Helicobacter sp. cultivated from human patients and is therefore a good alternative model of human gastric Helicobacter disease. We recently sequenced the genome of the H. bizzozeronii human strain CIII-1, isolated in 2008 from a 47-year old Finnish woman suffering from severe dyspeptic symptoms. In this study, we performed a detailed comparative genome analysis with H. pylori, providing new insights into non-pylori Helicobacter infections and the mechanisms of transmission between the primary animal host and humans.

Results

H. bizzozeronii possesses all the genes necessary for its specialised life in the stomach. However, H. bizzozeronii differs from H. pylori by having a wider metabolic flexibility in terms of its energy sources and electron transport chain. Moreover, H. bizzozeronii harbours a higher number of methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins, allowing it to respond to a wider spectrum of environmental signals. In this study, H. bizzozeronii has been shown to have high level of genome plasticity. We were able to identify a total of 43 contingency genes, 5 insertion sequences (ISs), 22 mini-IS elements, 1 genomic island and a putative prophage. Although H. bizzozeronii lacks homologues of some of the major H. pylori virulence genes, other candidate virulence factors are present. In particular, we identified a polysaccharide lyase (HBZC1_15820) as a potential new virulence factor of H. bizzozeronii.

Conclusions

The comparative genome analysis performed in this study increased the knowledge of the biology of gastric Helicobacter species. In particular, we propose the hypothesis that the high metabolic versatility and the ability to react to a range of environmental signals, factors which differentiate H. bizzozeronii as well as H. felis and H. suis from H. pylori, are the molecular basis of the of the zoonotic nature of H. heilmannii sensu lato infection in humans.

Background

Helicobacter pylori is established as the primary cause of gastritis and peptic ulceration in humans and has been recognised as a major risk factor for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma [1]. However, in gastric biopsies of a minority of patients (0.17-2.3%) with upper gastrointestinal symptoms, long, tightly coiled spiral bacteria, referred to non-H. pylori gastric Helicobacter species (NHPGH), have been observed [2,3]. Although NHPGH-associated gastritis is usually mild to moderate compared to H. pylori gastritis, severe complications of NHPGH infection have been reported, and it is important to note that MALT lymphoma is significantly more frequent in NHPGH-infected patients compared to those infected with H. pylori [4].

As a strictly human-associated pathogen, H. pylori is transmitted from human to human. In contrast, NHPGH are zoonotic agents for which animals are the natural reservoir [5]. Recently, the term H. heilmannii sensu lato has been proposed to be used to refer to the whole group of NHPGH detected in the human or animal stomach when only morphology and limited taxonomical data are available [3]. Indeed, H. heilmannii s.l. comprises seven described Helicobacter species: the porcine Helicobacter suis; the feline Helicobacter felis, Helicobacter baculiformis and Helicobacter heilmannii sensu stricto (s.s.); and the canine Helicobacter bizzozeronii, Helicobacter salomonis and Helicobacter cynogastricus [3]. These Helicobacter species are very fastidious microorganisms and difficult to distinguish from each others with conventional identification procedures. Due to difficulties in the isolation and identification of H. heilmannii s.l., its epidemiology in human infections remains unclear. Although development of specific isolation methods has allowed to identify several new species considered to be uncultivable (i.e.: H. suis and H. heilmannii s.s. [2,3]), up to now only H. bizzozeronii has been cultivated from the gastric mucosa of two human patients [6-8].

H. bizzozeronii, described as a new species in 1996 [9], is a canine-adapted species that is often found during a histological examination of gastric biopsies of dogs both with and without morphological signs of gastritis [10]. Virtually all animals are infected, and the pathogenic significance of H. bizzozeronii in dogs remains unknown [2,10]. Experimental infection studies using mice [11] and gerbils [12] have suggested that H. bizzozeronii appears to be associated with a lower pathogenicity than H. pylori or H. felis. Even in cases of heavy bacterial loading, the only pathological finding observed was focal apoptotic loss of gastric epithelial cells [12]. Despite the lack of connection between H. bizzozeronii and gastric diseases in both naturally and experimentally-infected animals, H. bizzozeronii has been associated in both human cases with severe dyspeptic symptoms [7,8]. Moreover, the human H. bizzozeronii strain CIII-1 was isolated from antrum and corpus biopsies that revealed chronic active gastritis [8], indicating that this species is able to induce similar injuries in the human gastric mucosa to those observed in H. pylori-infected patients.

Several genome sequences of H. pylori are available, and recently, the genomes of other gastric Helicobacter species were also published [13-16]. Among H. heilmannii s.l., the genomes of the type strain of H. felis [16], isolated from a cat, and of two strains of H. suis [15], both isolated from pigs, were determined. Recently, we sequenced the genome of the H. bizzozeronii human strain CIII-1, isolated in 2008 from a 47-year-old Finnish woman suffering from severe dyspeptic symptoms [17]. To our knowledge, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 is the only human H. heilmannii s.l. strain for which the genome is available and constitutes a keystone in the comprehension of non-pylori Helicobacter infections and of the mechanisms of transmission between the primary animal host and humans. Moreover, although the role of H. bizzozeronii in human gastric disease is limited compared to H. pylori, both of the species persistently colonise the same niche and possibly exploit similar mechanisms to interact with the host and induce gastritis. Thus, a comparative genome analysis between H. pylori and the human H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 would expand our knowledge of the biology of gastric Helicobacter spp. and of the pathogenesis of human gastritis.

In this study, we provide a detailed comparative genome analysis of H. pylori and the human H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 strain. We advance the hypothesis that the zoonotic nature of H. bizzozeronii, and, by extension of H. heilmannii s.l., is explicable from its high metabolic versatility, which probably supports the growth of this bacterium in a wide range of niches.

Results and discussion

General features and comparison with other taxa

The general features of the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome were previously described [17]. Briefly, the chromosome is similar in size and GC content (46%) to other sequenced gastric Helicobacter species [13,16] and includes 1,894 protein-coding sequences (CDSs) in a coding area of 93%. A putative function could be predicted for 1,280 (67.7%) of the CDSs, whereas 614 (32.4%) of the CDSs were annotated as hypothetical proteins. A summary of the features of the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome is provided in Table 1, and a circular plot of the chromosome showing GC content and GC skew is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Features of the Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome

| Number or % of total | |

|---|---|

| General features | |

| Chromosome size (bp) | 1,755,458 |

| G+C content | 46% |

| CDS numbers | 1,894 |

| Assigned function | 1,280 |

| Conserved hypothetical/hypothetical protein | 614 |

| Ribosomal RNA operons | 2 |

| tRNAs | 36 |

| Prophage | 1 |

| Genetic island | 1 |

| Number of plasmids (bp) | 1 (52,076) |

| IS elements | 5 |

| mini-IS elements | 22 |

| Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) | 80 |

| mono ≥ 9 | 71 |

| di ≥ 6 | 6 |

| tetra ≥ 4 | 0 |

| penta ≥ 4 | 2 |

| hepta ≥ 4 | 1 |

| RAST Subsystem Category Distribution* | |

| Cofactors, Vitamins, Prosthetic Groups, Pigments | 7.9% |

| Cell Wall and Capsule | 8.2% |

| Virulence, Disease and Defense | 1.6% |

| Potassium metabolism | 0.8% |

| Miscellaneous | 2.8% |

| Membrane Transport | 2.5% |

| Iron acquisition and metabolism | 0.3% |

| RNA Metabolism | 6.4% |

| Nucleosides and Nucleotides | 4.4% |

| Protein Metabolism | 18.1% |

| Cell Division and Cell Cycle | 1.7% |

| Motility and Chemotaxis | 5.9% |

| Regulation and Cell signaling | 0.3% |

| DNA Metabolism | 3.0% |

| Fatty Acids, Lipids, and Isoprenoids | 5.7% |

| Respiration | 5.9% |

| Stress Response | 2.4% |

| Metabolism of Aromatic Compounds | 0.6% |

| Amino Acids and Derivatives | 11.6% |

| Sulfur Metabolism | 0.3% |

| Phosphorus Metabolism | 0.6% |

| Carbohydrates | 8.8% |

| Gene classes | |

| Chemotaxis proteins | 23 |

| HAMP domain containg protein | 8 |

| Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) | 20 |

| HD domain containg protein | 2 |

| Redox-sensing PAS domain proteins | 1 |

| Restriction/modification systems | |

| Type I | 1(on plasmid) |

| Type II/IIS | 2 |

| Type III | 1(partial) |

| Transcriptional regulators | 3(σ28 σ54 σ70) |

| Two-component systems | |

| Response regulator | 10 |

| Sensor histidine kinase | 4 |

*percentage of 1,151 CDS included in 234 subsystems by RAST server (http://rast.nmpdr.org/)

Figure 1.

Circular representation of the Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 chromosome. From the outside in: the outer circle 1 shows the size in base pairs; circles 2 and 3 show the position of CDS transcribed in a clockwise and anti-clockwise direction, respectively (for color codes see below); circle 4 shows the position of insertion elements (IS and mini-IS, violet); circle 5 shows the results from Alien Hunter program from the lowest score (light pink) to the highest score (red) (threshold score value: 16.971); circle 6 shows the positions of the genomic island (brown) and prophage (orange); circle 7 shows a plot of G+C content (in a 10-kb window); circle 8 shows a plot of GC skew ([G_C]/[G+C]; in a 10-kb window). Genes in circles 2 and 3 are color-coded according to the following category: wine red, genes involved in central metabolism and respiration without orthologues in H. pylori; cyan, methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs); dark blue, type IV secretion system; sky blue, genes involved in acid acclimation; green, putative secreted virulence factors; pale green, glycosyltransferse gene cluster specific of H. bizzozeronii; pale grey, all other CDSs. ACC, acetophenone carboxylase; comB, Type IV secretion system; NAP, periplasmic nitrate reductase; AHD, allophanate hydrolase; GT, glycosyltransferase; NRS, nitrite reductase system; SNO, S- and N- oxidases; FDH, formate reductase system; PL, polysaccharide lyase.

The taxonomy of the best BLAST hits for the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 CDSs is shown in Table 2. Approximately 94% of the CIII-1 proteins have their best matches in proteins encoded by ε-proteobacteria, 97% of which belong to Helicobacteracae, and 95% are similar to proteobacterial proteins. H. felis is the most closely related organism, covering almost 50% of the best matches, followed by H. suis (36%) and H. pylori (2.7%). However, 33% of the CDSs have a homologue from H. pylori within the 5 best BLAST matches. Among the Campylobacter spp., C. rectus is the closest to H. bizzozeronii (0.9%; 16/1894) even though the homology is limited to the prophage region (see below). Matches to non-ε-proteobacteria are found within the Firmicutes (1.58%), γ-proteobacteria (0.9%), Bacteroides (0.6%) and also within the Eukaryota (0.9%).

Table 2.

Similarity of predicted Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 proteins to proteins from other taxa

| Taxon | Best match | Within best 5 matches |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | % | |

| Proteobacteria | 1,817 | 95.53 | 91.55 |

| Epsilon | 1,791 | 94.16 | 87.55 |

| Helicobacteraceae | 1,733 | 91.11 | 81.74 |

| Helicobacter felis | 937 | 49.26 | 19.09 |

| Helicobacter suis | 690 | 36.28 | 17.10 |

| Helicobacter pylori | 51 | 2.68 | 33.04 |

| Helicobacter mustelae | 12 | 0.63 | 1.90 |

| Helicobacter cinaedi | 8 | 0.42 | 1.67 |

| Helicobacter hepaticus | 8 | 0.42 | 1.67 |

| Helicobacter bilis | 8 | 0.42 | 1.25 |

| Helicobacter acinonychis str. Sheeba | 5 | 0.26 | 2.92 |

| Helicobacter winghamensis | 5 | 0.26 | 0.46 |

| Candidatus Helicobacter heilmannii | 3 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

| Wolinella succinogenes | 2 | 0.11 | 0.79 |

| Helicobacter cetorum | 2 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| Helicobacter canadensis | 1 | 0.05 | 0.63 |

| Helicobacter pullorum | 1 | 0.05 | 0.63 |

| Sulfuricurvum kujiense | 0 | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| Sulfurimonas autotrophica | 0 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| Sulfurimonas denitrificans | 0 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Helicobacter salomonis | 0 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Campylobacteraceae | 54 | 2.84 | 5.18 |

| Campylobacter rectus | 16 | 0.84 | 0.38 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 11 | 0.58 | 1.49 |

| Campylobacter upsaliensis | 9 | 0.47 | 0.77 |

| Campylobacter concisus | 6 | 0.32 | 0.24 |

| Campylobacter coli | 5 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| Campylobacter fetus | 4 | 0.21 | 0.41 |

| Campylobacter curvus | 2 | 0.11 | 0.29 |

| Campylobacter gracilis | 1 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Sulfurospirillum sp. | 0 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| Arcobacter butzleri | 0 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| Arcobacter nitrofigilis | 0 | 0.00 | 0.21 |

| Campylobacter showae | 0 | 0.00 | 0.20 |

| Campylobacter lari | 0 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Campylobacter hominis | 0 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Unclassified | 3 | 0.16 | 0.39 |

| Nautiliaceae | 1 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Alpha | 4 | 0.21 | 0.49 |

| Beta | 4 | 0.21 | 0.78 |

| Burkholderiales | 4 | 0.21 | 0.58 |

| Others | 0 | 0.00 | 0.20 |

| Gamma | 18 | 0.95 | 2.50 |

| Aeromonadales | 5 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Pasteurellales | 4 | 0.21 | 0.47 |

| Enterobacteriales | 2 | 0.11 | 0.45 |

| Pseudomonadales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.39 |

| Cardiobacteriales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| Vibrionales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Xanthomonadales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Oceanospirillales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Chromatiales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Thiotrichales | 0 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Legionellales | 0 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Others | 1 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Delta | 0 | 0.00 | 0.22 |

| Firmicutes | 30 | 1.58 | 2.80 |

| Clostridiales | 15 | 0.79 | 1.34 |

| Bacillales | 11 | 0.58 | 0.52 |

| Lactobacillales | 2 | 0.11 | 0.48 |

| Selenomonadales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Erysipelotrichales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Thermoanaerobacterales | 0 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Bacteroidetes/Chlorobi | 12 | 0.63 | 1.01 |

| Bacteroidales | 5 | 0.26 | 0.42 |

| Flavobacteriales | 3 | 0.16 | 0.25 |

| Sphingobacteriales | 2 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Unclassified | 1 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Chlorobiales | 1 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Cytophagales | 0 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Spirochaetes | 7 | 0.37 | 0.77 |

| Chloroflexi | 3 | 0.16 | 0.08 |

| Fusobacteria | 2 | 0.11 | 0.59 |

| Archaea | 2 | 0.11 | 0.18 |

| Actinobacteria | 1 | 0.05 | 0.37 |

| Fibrobacteres/Acidobacteria | 1 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Cyanobacteria | 1 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| Aquificae | 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Deferribacteres | 1 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Tenericutes | 1 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Planctomycetes | 0 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Deinococcus-Thermus | 0 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Chlamydiae/Verrucomicrobia | 0 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Synergistetes | 0 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| Thermotogae | 0 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Nitrospirae | 0 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Phage/Plasmid/Virus | 6 | 0.32 | 0.49 |

| Eukaryota | 17 | 0.89 | 1.45 |

We further compared the genome of H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 with the genomes of 10 human H. pylori strains to identify proteins that are unique to H. bizzozeronii as well as proteins found in H. pylori but lacking in H. bizzozeronii. The H. pylori core genome and H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 have 1,034 groups of orthologues in common, to which 1,052 CDSs from CIII-1 belong. Moreover, 412 groups are found in H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 and in at least two H. pylori strains, and 192 groups are common in CIII-1 and in at least one H. pylori strain. The H. pylori core genome contains 151 groups of unique orthologues while a total of 562 CDSs are unique to H. bizzozeronii CIII-1. Among the 562 unique H. bizzozeronii CDSs, a putative function was predicted for only 147 (26%). Each of these 147 CDSs was searched against the NCBI nr database using BLASTp to identify homologies with other H. pylori strains. A total of 59 out of the 147 CDSs showed a homology to proteins of at least one H. pylori strain, restricting the number of unique H. bizzozeronii CDSs with a predicted function to 88. Excluding the proteins associated either with bacteriophage or with plasmid replication, the functions of the majority of the unique H. bizzozeronii genes are linked to chemotaxis and metabolism (Figure 1).

General features involved in the colonisation of the stomach: acid acclimation, mobility and chemotaxis

As described for the H. pylori genome [18], the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome contains a complete urease gene cluster (ureABIEFGH; HBZC1_10430 to HBZC1_10490) that is essential for acid acclimation and pH homeostasis, crucial mechanisms for the gastric colonisation. The urease gene cluster showed the same syntheny as in H. pylori. Unlike the other animal gastric Helicobacter species, H. felis and H. mustelae [13,16], H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 lacks the additional urease genes (ureAB2). Other essential mechanisms for the colonisation of the gastric mucosa participate in pH homeostasis [18]: H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 contains the periplasmic α-carbonic anhydrase orthologue HBZC1_14670, which contributes to the urease-dependent response to acidity in H. pylori [19], but lacks an orthologue for the β-carbonic anhydrase. In addition, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 carries both the asparagine and glutamine deamidase-transport systems of AnsB (HBZC1_05200 and HBZC1_12160) plus DcuA (HBZC1_00140) and γGT (HBZC1_08080) plus GltS (HBZC1_14360) that contribute to periplasmic ammonia production in H. pylori and may have a possible role in the resistance to weakly acidic conditions and in the pathogenesis of gastritis [20]. A unique feature of H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 that might also contribute to acid acclimation is the presence of two copies of a putative allophanate hydrolase (HBZC1_04550 and HBZC1_09470). This enzyme catalyses the second reaction of the two-step degradation of urea to ammonia and CO2 and is usually found adjacent to a biotin-containing urea carboxylase gene (HBZC1_04560 and HBZC1_09490, respectively), which functions as an allophanate synthase from urea [21]. Orthologues of allophanate hydrolase have been found to be widely distributed among several subdomains of Bacteria, including Campylobacter species and H. felis, but their role in urea degradation has been demonstrated only in the environmental α-proteobacteria species Oleomonas sagaranensis [21]. In H. bizzozeronii the orthologue could contribute to the cytoplasmic degradation of urea in combination with urease. However, other functions, such as the degradation of aromatic compounds [22], could not be excluded.

Motility is fundamental for colonisation of the mucosa by gastric Helicobacter species [23], and, similarly to other flagellated bacteria, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 harbours a large group of genes distributed widely in the genome, encoded by the fla, flg, flh and fli gene families, which are involved in the regulation, secretion and assembly of flagella [24].

Chemotactic pathways that are governed by two-component regulatory systems, histidine kinase proteins and regulatory proteins, modulate the direction and speed of motility using responses of specific signals detected by receptors formed by methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs). The repertoire of the chemotactic signal pathways of a microorganism is correlated to the environments it can transfer, the hosts it colonises and the diseases it can cause [25]. Despite the similar number of two-component systems, 4 histidine kinases and 10 regulatory proteins [26], H. bizzozeronii harbours five times more MCPs than H. pylori. Twenty MCPs, one containing a PAS domain, were detected in the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome compared to the four predicted in H. pylori 26695 (Figure 1; see additional file 1: Table S1) [26]. The abundance of predicted MCPs, similarly observed in H. felis [16], indicates an elaborate sensing capability of H. bizzozeronii that allows the bacterium to survive in different ecological niches and probably supports its capability to transfer between different hosts.

The central intermediary metabolism

Understanding the metabolic properties of any pathogen is crucial to gain a full picture of the pathogenicity of related diseases. For example, C. jejuni is a more versatile and metabolically active pathogen than the more specialised H. pylori. The metabolic versatility of C. jejuni enables the bacterium to survive in different environments and to colonise a variety of animal species, while the high specialisation of H. pylori is probably the result of a process of adaptation to the human stomach [27]. Although H. pylori and H. bizzozeronii colonise similar niches, an important difference between these two species is the capability of H. bizzozeronii to move from a dog to a human host [2]. The central metabolism of H. bizzozeronii, which can be inferred from the genome of the human strain CIII-1, appears to be more flexible than that of H. pylori and could explain the zoonotic nature of this species.

As observed for H. pylori [28,29], even though the glycolysis pathway is incomplete because of the lack of phosphofructokinase, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 may use glucose as a source of energy through the pentose phosphate reactions and the Entner-Doudoroff pathway. However, in contrast to what was observed in H. pylori, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 possess three genes organised in a single operon that are required for glycerol metabolism: glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (glpD, HBZC1_03150), glycerol kinase (glpK, HBZC1_03160 and HBZC1_03170) and a glycerol uptake facilitator protein (glpP, HBZC1_03180). Glycerol-3-phosphate is a central intermediate in glycolysis and in phospholipid metabolism [30]. The enzyme glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase converts glycerol-3-phosphate to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, which can enter the glycolysis pathway, conferring significant metabolic advantages on this species.

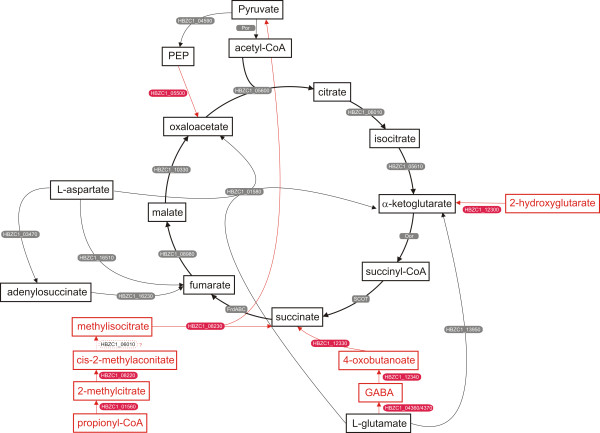

The absence of obvious homologues of succinyl-CoA synthetase indicates the presence of the alternative citric acid cycle (CAC), which has been described in H. pylori [31] (Figure 2; see additional file 1: Table S2). However, in contrast to H. pylori [27], the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome contains several genes involved in the anaplerotic replenishment of oxaloacetate, succinate and α-ketoglutarate (Figure 2; see additional file 1: Table S2). Like C. jejuni [27], the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome includes a homologue of phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP) carboxylase (HBZC1_05500) that may function in oxaloacetate synthesis. In addition, the genome harbours genes encoding enzymes potentially involved in the 2-methylcitric acid cycle (HBZC1_01560; HBZC1_08220; HBZC1_08230; HBZC1_06010) that produces succinate and pyruvate from the breakdown of propionate [32]. Moreover, a group of three genes, 4-aminobutyrate transaminase (HBZC1_12340), NADP+-Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (HBZC1_12330) and an amino acid permease (HBZC1_12320), share homology with the gabDTP operon of E. coli but do not have orthologues in any of the H. pylori sequenced genomes. These genes are potentially involved in the production of succinic acid from the degradation of polyamines or γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [33]. The synthesis of GABA from L-glutamate might occur in H. bizzozeronii trough the action of a glutamate decarboxylase (HBZC1_04360/HBZC1_04370) which does not have orthologue in H. pylori. Downstream of the putative H. bizzozeronii gabDTP operon, there are two gene homologues to the E. coli carbon starvation-induced protein (csiD, HBZC1_12310) and L-2-hydroxygluturate oxidase (lhgO, HBZC1_12300). In E. coli, lhgO, located immediately downstream of csiD and upstream of the gabDTP operon, plays a role the recovering α-ketoglutarate, an intermediate in CAC, reduced by other enzymes [34]. In E. coli, all of these genes are regulated by the CsiR repression and σS induction acting on csiDp during carbon starvation and the stationary phase [35]. H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 lacks both of these transcriptional regulators but it contains a homologue of carbon-starvation regulator (CsrA, HBZC1_09070) that controls the H. pylori response to environmental stress [36] and could play a similar role in H. bizzozeronii.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the central metabolism (predicted citric acid cycle and anaplerotic reactions) of Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1. In red the reactions predicted to be present in H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 but not in H. pylori. In black the reactions predicted to be in common in both Helicobacter species. Reaction for which no predictable enzymes were found in the genome is indicated by dotted line. The H. bizzozeronii gene numbers are indicated in boxes.

Finally, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 harbours a cluster of 4 conserved genes (HBZC1_00410 to HBZC1_00460), annotated as acetophenone carboxylase subunits 1 to 4, which show a low homology with microbial hydantoinases. This group of genes is located near to the SCOT (scoAB, HBZC1_00390 and HBZC1_00400) and acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase (fadB, HBZC1_00380) genes. A similar gene cluster, encoding a set of enzymes capable of metabolizing acetone to acetyl-CoA, has also been described in H. pylori (scoAB, fadB and acxABC) [37]. However, the homology between the H. pylori acxABC and the H. bizzozeronii acetophenone carboxylase gene cluster is very low (<30%), indicating that the H. bizzozeronii genes could be involved in an alternative pathway.

Physiology of microaerobic growth

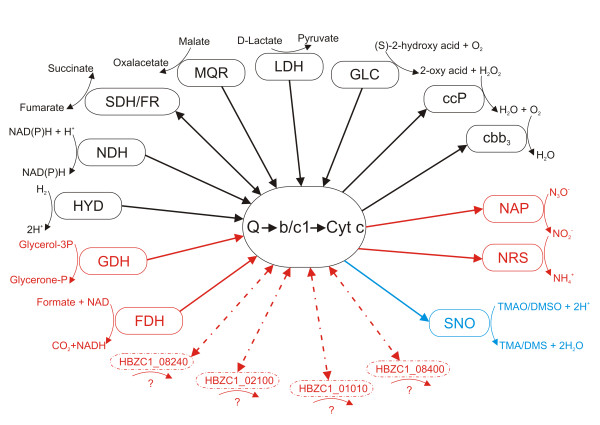

The complexity of the electron transport chain is another important element in the ability of bacteria to grow under a variety of environmental conditions, determining the metabolic flexibility of the bacterium based on the variety of electron donors and acceptors that can be used to support growth [38]. The respiratory chain in H. bizzozeronii appears to be highly branched and more complex than described for H. pylori (Figure 3; see additional file 1: Table S2).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the respiratory pathway in Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1. In red the reactions predicted to be present in H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 but not in H. pylori. In black the reactions predicted to be in common in both Helicobacter species. In blue TMAO/DMSO reduction which could be predicted also in H. pylori but a complete set of enzyme is not present. The arrows indicate the direction of the electrons to or from the membrane-bound electron transport chain. Dashed lines indicate that the direction of the electrons is unknown. Enzymes catalyzing key reactions are indicated in boxes. FDH, formate dehydrogenase; HYD, hydrogenase; NRS, nitrite reductase system; SNO, S- and N- oxidases; GDH, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NDH, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase; SDH/FR, succinate dehydrogenase/fumarate reductase; MQR, malate-quinone-reductase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GLC, glycol oxidase; NAP, periplasmic nitrate reductase; Q, quinone; Cyt b/c1, quinone cytochrome oxidoreductase; Cyt c, cytochrome c; cbb3, cytochrome c oxidase; ccP, cytochrome c peroxidase.

In addition to hydrogenase HydABCDE (from HBZC1_10200 to HBZC1_10150) and other dehydrogenases in common with H. pylori (Figure 3; see additional file 1: Table S2) [39], the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome contains a putative formate dehydrogenase enzyme complex, organised in a operon (from HBZC1_13510 to HBZC1_13550), which could enable the bacteria to use formate as an electron donor, as observed in other ε-proteobacteria [38]. In addition, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (HBZC1_03150) provides H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 an extra possibility for substrate-derived electrons to be donated to the membrane-bound electron transport chain.

H. bizzozeronii requires oxygen for growth and is unable to survive under anaerobic conditions [9]. As previously observed in H. pylori, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 possesses only one terminal oxidase, ccoNOQP (from HBZC1_08510 to HBZC1_08540), which encodes a cytochrome cb-type enzyme, the major factor in aerobic respiratory metabolism [38]. In addition to using an oxygen-dependent electron transport, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 could use as electron acceptors fumarate by a fumarate reductase system (FrdABC, from HBZC1_01900 to HBZC1_01920), as described in H. pylori [39]. However H. bizzozeronii could also utilize nitrate and nitrite as electron acceptors. This characteristic had been already shown in C. jejuni but not in H. pylori [38]. Nitrate could be reduced by a periplasmic nitrate reductase system (NapAGH, from HBZC1_08800 to HBZC1_08830; NapB, HBZC1_04310; NapFD; HBZC1_03530-HBZC1_03540), which differs from the C. jejuni system for the absence of NapL homologues and by the fact that it is not organised in a single operon (Figure 1) [38]. Moreover, although a clear C. jejuni nitrite reductase orthologue is absent, the genome of H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 contains a cluster of two genes encoding a putative periplasmic nitrite reductase (HBZC1_10540) and a cytochrome-c nitrite reductase subunit c552 domain containing protein (annotated as hydroxylamine oxidoreductase; HBZC1_10550), suggesting that nitrate could be used in anaerobic respiration by this species. In addition to using nitrate and nitrite, H. bizzozeronii could also use S- or N-oxides as electron acceptors, as observed in other ε-proteobacteria [27]. In fact, trimethylamine-n-oxide (TMAO) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) could be reduced by a putative periplasmic system, a homologue of Cj0264c/Cj0265c (HBZC1_10800/HBZC1_10810) [38]. In H. pylori a putative trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase is present (HP0407 in H. pylori 26695; 41% amino acid identity with HBZC1_10810 over 93% of sequence length). Although a homologue of the monoheme c type cytochrome (HBZC1_10800/Cj0265c) is absent, we cannot exclude that H. pylori may also be able to use TMAO/DMSO in respiration through a different pathway.

Other genes possibly involved in the electron transport chain that are present in the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome without clear homologues in H. pylori are: two copies of an NAD(P)H-dependant oxidoreductase (HBZC1_02100 and HBZC1_08240), a pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxidoreductase (HBZC1_01010) and an aldo/keto reductase (HBZC1_08400). Although it is not possible to predict the functions of these genes, their presence increases the complexity of the electron transport chain of H. bizzozeronii and clearly differentiates this species from H. pylori.

Like H. pylori [39], because of its microaerophilic requirements, H. bizzozeronii expresses several defence mechanisms against oxidative stress. These include an iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase SodB (HBZC1_11160/11150), catalase enzyme KatA (HBZC1_12240), Cytocrome-c peroxidase (HBZC1_05800) and alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (HBZC1_01800). Moreover, because metal ions like iron and nickel favour the creation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the detoxification of ROS needs to be coupled tightly to the control of intracellular metal concentrations, ensuring metal ion homeostasis by the regulation of metal uptake, export and storage [40]. H. bizzozeronii contains all of the genes involved in nickel and iron uptake, storage and metabolism that have been described in other Helicobacter species [13,40].

Features involved in the interaction with the host: surface structures and secreted proteins

H. bizzozeronii is able to persistently colonise the stomach of both dogs [2] and humans [6-8]. Therefore, the bacteria need to constantly interact with the hosts directly, using fixed bacterial surface molecules that mediate adherence, and indirectly, by the secretion of soluble proteins that act on respective host receptors.

Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) play important roles in the interaction with the host by mediating the adhesion to the mucosa and, therefore, the colonisation of the stomach and modulating the host immune response. Moreover, OMPs are essential for the general metabolism of the bacteria, preserving the selective permeability of the outer membrane to different substrates [41]. The H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome encodes a total of 51 putative OMPs (see additional file 1: Table S3) that are phylogenetically related to the five OMP families described in H. pylori [42]. Twenty of the H. bizzozeronii OMPs are similar to the Family 1 OMPs of H. pylori that include both Hop and Hor proteins. In contrast to the common finding that H. pylori attaches to the membrane of epithelial cells using different adhesive structures [42], studies on non-pylori Helicobacter species in mice and Mongolian gerbils [11,43] and in dogs [44] showed no evidence of a tight attachment to gastric epithelial cells by H. bizzozeronii. In fact, although 8 out a total of 20 H. bizzozeronii Family 1 OMPs belong to the Hop category, none of them could be considered as orthologues of the BabA, BabB or SabA adhesins, which play a major role in H. pylori adhesion to the gastric mucosa [45]. However, H. bizzozeronii was found in the intracellular canaliculi and in the cytoplasm of the parietal cells of canine gastric mucosa [44]. Although it is not clear how this Helicobacter sp. penetrates into the cytoplasm of parietal cells, a possible role of the H. bizzozeronii Hop proteins as adhesins with a different receptor specificity from that described in H. pylori, should be considered. Excluding the hofA homolog (HBZC1_6200), the other eight H. bizzozeronii hof genes are organised in a single operon (hofHHBFEGCD; from HBZC1_06760 to HBZC1_06830). This region is characterised by an anomalously low GC content and was identified as potential laterally acquired DNA by the Alien Hunter program [46]. Hof family was identified from the H. pylori proteome based on a heat-stable 50 KDa OMP [41], but its role is still unknown. Three of the H. bizzozeronii OMPs belong to Hom Family 3, and a total of 5 putative efflux pump OMPs (Family 5) were identified. Moreover, 5 iron-regulated OMPs (Family 4) were detected in the H. bizzozeronii genome. Finally, the remaining 10 H. bizzozeronii OMPs are currently unclassified, including the putative VacA-paralog (HBZC1_11860/11850), a peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (HBZC1_14500), the membrane-associated lipoprotein Lpp20 (HBZC1_01250) and a putative protease (HBZC1_01500).

The communication between a microbial pathogen and its host occurs also due to the recognition of cell surface glycomolecules, including lipopolysaccharides (LPS), capsular polysaccharides and N- and O-glycoproteins, the structure of which depends of the presence and functional transcription of the genes encoding glycosyltransferases (GTs) [47]. A total of 24 GTs were annotated in the genome of H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 (see additional file 1: Table S4), 22 of which belong to 10 distinct GT-families according to the sequence-based classification of GTs available in the CAZy database [48]. In addition, the genome of H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 harbours 20 orthologues of genes implicated in the biosynthesis of glycan structures in other bacterial species (see additional file 1: Table S4), including a complete flagellin O-glycosylation pathway that is essential for flagella assembly and motility [49]. The LPS of H. pylori, which displays Lewis blood-group (Le) antigens, is a primary host-interacting structure, and several lines of evidence indicate that it is involved in host-adaptation and virulence [50]. Distinct from H. pylori, H. bizzozeronii produces a predominantly low-molecular-weight LPS and does not apparently exhibit a molecular mimicry of Lewis and other blood group antigens [51]. However, anti-H. pylori LPS core antibodies reacted with the H. bizzozeronii LPS, indicating a shared epitope between these two species [51]. Several genes are involved in the biosynthesis of LPS in H. bizzozeronii and are dispersed across the genome as they are described in H. pylori [26]. In addition to the conserved genes of the LPS biosynthesis pathway (see additional file 1: Table S4), the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome includes a putative α1,3-fucosyltransferase (GT10; HBZC1_11830), a tandem of two putative galactosyltransferases (GT25; HBZC1_4780/4770/4760 and HBZC1_4800/4790) that are fragmented due to the presence of homopolymeric runs, a putative α1,3-sialyltransferase (GT42; HBZC1_02560) and other putative glycosyltransferases that belong to GT-family 2 or 4 or are unclassified. Structural analysis of the H. bizzozeronii LPS have shown the presence of fucose [51] and sialyl-lactoseamine (M. Rossi, unpublished data), confirming the role of GT10, GT25 and GT42 in the modification of the oligosaccharide region of LPS. However, several other GTs cannot be confidently included in a specific biosynthesis pathway. Among these genes, a cluster of 6 GTs (from HBZC1_07440 to HBZC1_07490) and a putative polysaccharide deacetylase (HBC1_07500) are particularly interesting (Figure 1). Orthologues of these genes are not found in H. pylori. Although some of these genes have homologues in the H. felis and H. suis genomes [15,16], the number and synteny of the genes appear to be specific characteristics of H. bizzozeronii.

The extracellular proteins of H. pylori are known to mediate pathogen-host interaction during infection [52]. To export proteins H. bizzozeronii, as a gram-negative bacterium, utilises the Sec or the twin-arginine secretion (Tat) systems to transport proteins into the periplasmic space and uses different approaches to move the proteins through the outer membrane [53]. In H. bizzozeronii CIII-1, the Sec system, which lacks a homologue to SecB, is dispersed through the genome, as it is in other Helicobacter spp. [13,53] and the Tat system is composed of three genes that are homologous to the TatABC traslocation proteins TatA (HBZC1_10870) and YatBC (HBZC1_10370-10380) and a putative deoxyribonuclease that is orthologous to H. pylori tatD (HBZC1_14750). Both of the systems recognise an N-terminal signal peptide of the protein that is required for translocation [53]. More than 200 proteins were predicted to have a Sec signal peptide using the SignalP software [54] (data not shown). However, only 50 proteins, 22 of which harbour a signal peptide, appear to be located in the periplasmic space or outside of the outer membrane, as predicted using the PSORTb v3 tool [55] (Table 3). Nevertheless, the subcellular locations of more than 600 H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 proteins were not identified. Several proteins that share a clear homology with excreted proteins in H. pylori were predicted to be located in the cytoplasm, indicating that the repertoire of secreted proteins in H. bizzozeronii could be considerably different from what predicted using PSORTb.

Table 3.

List of putative Helicobacter bizzozeronii secreted proteins predicted by PSORTbv3

| CDS Locus_Tag | Predicted function | Localization | Sec SP1 | Tat SP2 | SpII3 |

H. pylori orthologue CDS Locus_tag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBZC1_00340 | Oligopeptide ABC transporter, periplasmic oligopeptide-binding protein OppA | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP1252 |

| HBZC1_00890 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-)4 |

| HBZC1_00900 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | + | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_00910 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | + | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_01330 | Flagellar hook protein FlgE | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP0870 |

| HBZC1_01540 | Flagellar hook-associated protein FlgK | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP1119 |

| HBZC1_01610 | HtrA protease/chaperone protein/Serine protease | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP1019 |

| HBZC1_02310 | Membrane-anchored cell surface protein | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_02430 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | + | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_03080 | Flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgC | Periplasmic | - | - | - | HP1558 |

| HBZC1_03090 | Flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgB | Periplasmic | - | - | - | HP1559 |

| HBZC1_04310 | Nitrate reductase cytochrome c550-type subunit | Periplasmic | + | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_04340 | Flagellin | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP0115 |

| HBZC1_05160 | Soluble lytic murein transglycosylase | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP0649 |

| HBZC1_05800 | Cytochrome c551 peroxidase | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP1461 |

| HBZC1_05960 | Putative amino-acid transporter periplasmic solute-binding protein | Periplasmic | + | - | + | HP1172 |

| HBZC1_06690 | Sel1 domain-containing protein repeat-containing protein | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_07110 | Flagellar hook-associated protein FlgL | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP0295 |

| HBZC1_07220 | Hypothetical protein | Extracellular | + | - | + | (-) |

| HBZC1_07230 | Hypothetical protein | Extracellular | - | - | + | (-) |

| HBZC1_07880 | Hypothetical protein | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_08080 | Gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP1118 |

| HBZC1_08620 | Flagellar hook-length control protein FliK | Periplasmic | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_08630 | Flagellar basal-body rod modification protein FlgD | Periplasmic | - | - | - | HP0907 |

| HBZC1_08640 | Flagellar hook protein FlgE | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP0908 |

| HBZC1_08800 | Periplasmic nitrate reductase | Periplasmic | - | + | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_08840 | Flagellar P-ring protein FlgI | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP0246 |

| HBZC1_09700 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | + | - | + | HPSH_03725 |

| HBZC1_10550 | Cytochrome c nitrite reductase subunit c552 | Periplasmic | + | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_10810 | trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP0407 |

| HBZC1_10890 | mJ0042 family finger | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_11140 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | + | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_11160 | Superoxide dismutase | Periplasmic | - | - | - | HP0389 |

| HBZC1_11330 | YgjD/Kae1/Qri7 family protein | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP1584 |

| HBZC1_11450 | Flagellar hook-associated protein FliD | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP0752 |

| HBZC1_12200 | Hypothetical protein | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_12220 | Hypothetical protein | Periplasmic | + | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_12240 | Catalase | Periplasmic | - | - | - | HP0875 |

| HBZC1_12430 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP0198 |

| HBZC1_13860 | Cytochrome C553 (soluble cytochrome f) | Periplasmic | + | - | - | jhp1148 |

| HBZC1_13880 | Flagellin | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP0601 |

| HBZC1_14010 | Outer membrane protein | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_14040 | Flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgG | Extracellular | - | - | - | HP1092 |

| HBZC1_14510 | TolB protein | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP1126 |

| HBZC1_14760 | Membrane-bound lytic murein transglycosylase D | Periplasmic | + | - | - | HP1572 |

| HBZC1_15010 | Arginine decarboxylase | Periplasmic | - | - | - | HP0422 |

| HBZC1_16410 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_16420 | Hypothetical protein (sel 1 domain repeat containing protein) | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

| HBZC1_17210 | Hypothetical protein | Periplasmic | - | - | - | HPG27_960 |

| HBZC1_17260 | Endonuclease I | Extracellular | - | - | - | (-) |

1The Sec specific signal peptide predicted using SignalP-HMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/); probability score cut off 0,500

2The Tat specific signal peptide predicted using TatP 1.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TatP/)

3The signal peptide SpII of lipoproteins was predicted using LipoP 1.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/LipoP/)

4No orthologues in H. pylori; BLASTP against nr database: two proteins with amino acid identity greater than 40% over 80% sequence length were considered homologues

It has been shown in H. pylori that some proteins could be exported from the cytoplasm to the extracellular milieu or directly to the cytoplasm of the host through Sec-independent secretion systems [53]. H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome lacks orthologues of CagPAI that encode a type IV secretion system responsible in H. pylori of the translocation of the effector protein CagA into the cytosol of the host [23]. In addition to containing the secretion system that exports the flagella subunit across the membrane, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 harbours a type IV secretion systems derived from genes orthologues of comB2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 that are organised in different operons dispersed throughout the genome (Figure 1; see additional file 1: Table S5). In H. pylori, the comB components are required for uptake DNA by natural transformation [56], and its orthologues likely encode same function in H. bizzozeronii.

H. bizzozeronii is able to induce similar injuries in the human gastric mucosa as is H. pylori, indicating that both of the species express similar virulence factors. Although VacA and CagA homologues are missing, other virulence-associated genes described in H. pylori are present in the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome and typically share a high degree of similarity. These virulence factors could contribute to the disease outcome and include the following: the immunomodulator NapA (HBC1_08880); the peptidyl propyl-cis,trans-isomerase (HBZC1_06110), involved in the TLR4-dependent NF-κB and in AP1 activation of macrophages [57]; the tumour necrosis factor alpha-inducing protein (Tipα, HBZC1_02220), described in H. pylori as a carcinogenic factor [58]; and the secreted serine protease (HtrA, HBZC1_01610), which cleaves the ectodomain of the cell-adhesion protein E-cadherin providing an access to the intercellular space for H. pylori [59] (Figure 1). A putative virulence factor in H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 that does not have homologues in any H. pylori is HBZC1_15820, encoding a polysaccharide lyase belonging to Family 8 (Figure 1) [48]. A similar gene was found in the genome of H. felis [16], but a homologue is absent in all of the other sequenced ε-proteobacteria. Polysaccharide lyases are eliminases that cleave acidic polysaccharides, such as glycosaminoglycans, at specific glycosidic linkages [60]. Family 8 includes hyaluronate, chondroitin AC/ABC and xanthan lyases that have been isolated from several bacterial species, both non-pathogenic and pathogenic, including Bacillus spp., Penibacillus spp., Proteus spp., Clostridium spp., Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp. [48]. In certain pathogenic species the polysaccharide lyases represent a virulence factor that is important, for example in Staphylococcus aureus, in the early stages of infections [61]. The role of this putative polysaccharide lyase in both H. bizzozeronii and H. felis is completely unknown and requires further study.

Genome plasticity

H. bizzozeronii is well adapted to colonise the stomach of dogs [44] and has probably coevolved with its natural host, as has been demonstrated for other gastric Helicobacter species [1,14]. However, H. bizzozeronii is not strictly restricted to the canine gastric mucosa but is able to colonise different hosts [2]. Therefore, when transferring from dogs to humans, H. bizzozeronii necessarily undergoes intensive changes to adapt to a new host. As is the case for H. pylori [1], the ability of H. bizzozeronii for ongoing host-adaptation is related to its high level of genome plasticity.

The H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome lacks multiple genes in the methyl-directed mismatch repair system (MMR), similar to other ε-proteobacteria [13,62]. A consequence of such a defect in the MMR is the formation and extension of multiple hypervariable simple sequence repeats (SSRs), potentially responsible for the phase variation in H. bizzozeronii. SSRs are subject to slipped-strand mutations, therefore inducing frameshift of the gene if the repeats are located in a protein-coding region or alteration of the gene expression when the repeats affect the promoter [63]. It has been shown that the physiological role of SSRs may not be limited to phase variation, but can include reorganisation of the chromosome, influence on protein structure and function, and possible antisense regulation [16,64,65]. A total of 80 SSRs, 71 of which are homopolymeric runs of ≥9 units of a single nucleotide, were detected dispersed across the H bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome, with 64 (the majority) located inside the coding regions. The frames of 54 genes are affected by the slipped-strand mispairing associated with SSRs. After the exclusion of essential genes which are unlikely subjected to phase variation by slipped-strand mispairing (i.e., tRNA-guanine transglycosylase, cell division protein FtsK, DNA polymerase and spermidine synthase) we were able to identify a total of 43 potentially phase-variable genes (Table 4). Similar number of contingency genes was also described in H. pylori [66], and, as observed in C. jejuni and H. pylori, the dominant function of the contingency genes in H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 is the modification at either the protein or carbohydrate level of the surface architecture, suggesting that these structures play an important role in the adaptation to different hosts [67,68].

Table 4.

Putative phase variable genes of Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1

| Repeat unit | Length(bp) | Region | Localization1 | CDS Locus_Tag2 | Predicted function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycan biosynthesis | ||||||

| C | 20 | 1,090,089..1,090,108 | 5' | HBZC1_11830 | Alpfa(1,3)-Fucosyltransferase (glycosyltransferase Family GT10) | |

| C | 19 | 448,597..448,615 | M | HBZC1_04780/HBZC1_04770/HBZC1_04760 | Putative Beta-Galactosyltransferase (glycosyltransferase Family GT25) | |

| C | 19 | 449,444..449,462 | 5' | HBZC1_04800/HBZC1_04790 | Putative Beta-Galactosyltransferase (glycosyltransferase Family GT25) | |

| C | 14 | 237,793..237,806 | 5' | HBZC1_02530/HBZC1_02540 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase | |

| G | 13 | 339,856..339,872 | M | HBZC1_03690/HBZC1_03680 | Glycosyltransferase Family GT4 | |

| CT | 13 | 1,310,060..1,310,085 | M | HBZC1_14140 | Glycosyltransferase Family GT4 | |

| CACACAA | 13 | 706,715..706,800 | M | HBZC1_07440 | Glycosyltransferase Family GT4 | |

| Cell-surface-associated proteins | ||||||

| G | 15 | 478,890..478,904 | 5' | HBZC1_05060 | Hypothetical protein (putative HcpA) | |

| G | 10 | 732,027..732,038 | M | HBZC1_07730/HBZC1_07740 | CBS domains containing protein (homologue of HP1490 - TolC efflux pump) | |

| G | 15 | 1,677,616..1,677,630 | 5' | HBZC1_18160 | Putative ATP/GTP binding protein | |

| G | 9 | 58,965..58,973 | 5' | HBZC1_00570 | Massive surface protein (MspC) | |

| G | 9 | 640,616..640,624 | M | HBZC1_06770 | Outer membrane protein | |

| C | 9 | 809,713..809,721 | M | HBZC1_08590/HBZC1_08580 | Outer membrane protein (omp30) | |

| A | 9 | 1,401,250..1,401,258 | 5' | HBZC1_15140/HBZC1_15150 | Outer membrane protein | |

| C | 9 | 666,243..666,252 | M | HBZC1_06970 | Putative paralog of HpaA | |

| C | 9 | 880,014..880,022 | 5' | HBZC1_09290 | Hypothetical protein | |

| T | 9 | 167,433..167,441 | M | HBZC1_01860 | Cardiolipin synthetase (phosholipase D) | |

| C | 9 | 1,364,186..1,364,194 | 5' | HBZC1_14770 | Rare lipoprotein A precursor | |

| C | 9 | 611,706..611,714 | 5' | HBZC1_06460 | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | |

| G | 9 | 831,049..831,057 | 5' | HBZC1_08750/HBZC1_08760 | Flagellar assembly protein FliH | |

| A | 9 | 813,507..813,515 | 5' | HBZC1_08620 | Flagellar hook-length control protein FliK | |

| C | 9 | 1,380,513..1,380,521 | M | HBZC1_14960 | Hypothetical protein (probable membrane protein) | |

| G | 9 | 1,581,243..1,581,251 | 5' | HBZC1_17050 | Omp | |

| AG | 8 | 516,821..516,838 | M | HBZC1_05450/HBZC1_05460 | Membrane protein containing sulfatase domain | |

| TC | 6 | 1,716,985..1,716,996 | M | HBZC1_18530 | Membrane protein containing sulfatase domain | |

| CAGCA | 14 | 1,532,941..1,533,010 | 5' | HBZC1_16470 | HopZ | |

| Restriction/Modification system | ||||||

| AC | 20 | 823,472..823,513 | 3' | HBZC1_08670/HBZC1_08280 | Type I restriction-modification system, DNA-methyltransferase subunit M and S | |

| Stress associated proteins | ||||||

| C | 9 | 204,956..204,964 | M | HBZC1_02170 | Cold-shock DEAD-box protein A | |

| G | 10 | 1,343,484..1,343,493 | M | HBZC1_14490 | Putative periplasmic protein contains a protein prenylyltransferase domain | |

| Other proteins | ||||||

| G | 9 | 886,063..886,071 | M | HBZC1_09350/HBZC1_09360 | Hypothetical protein (homolog of putative heterodisulfide reductase H. suis) | |

| G | 17 | 981,720..981,736 | M | HBZC1_10620/HBZC1_10630 | Hypothetical protein (Sel1 domain-containing protein) | |

| C | 16 | 1,314,541..1,314,556 | 5' | HBZC1_14170/HBZC1_14180 | Hypothetical protein | |

| G | 9 | 177,594..177,602 | M | HBZC1_01940 | Hypothetical protein | |

| C | 10 | 372,167..372,176 | 5' | HBZC1_04030 | Hypothetical protein | |

| A | 9 | 571,554..571,562 | 5' | HBZC1_06030 | Hypothetical protein | |

| C | 13 | 886,063..886,071 | M | HBZC1_10080 | Hypothetical protein | |

| C | 17 | 986,120..986,136 | M | HBZC1_10650 | Hypothetical protein | |

| G | 9 | 1,135,720..1,135,728 | 5' | HBZC1_12200 | Cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid contains Rieske domain | |

| C | 14 | 1,235,708..1,235,721 | 5' | HBZC1_13300 | Hypothetical protein | |

| C | 9 | 1,380,536..1,380,544 | M | HBZC1_14960 | Hypothetical protein | |

| G | 10 | 1,458,356..1,458,364 | M | HBZC1_15990 | Hypothetical protein | |

| G | 9 | 1,571,406..1,571,414 | M | HBZC1_16940 | Hypothetical protein | |

| G | 13 | 1,659,328..1,659,340 | 5' | HBZC1_17930 | Hypothetical protein (contains LexA/Signal peptidase domain) | |

1localization of the SSR in the 5' terminal part (5'), 3' terminal part (3') or in the middle (M) of the corresponding CDS

2when modifying the repeat length allows to merge two or more adjacent CDSs, the respective locus tags are indicated in the table separated by a slash

The extreme genetic diversity observed among the H. pylori strains appears to also be generated by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) as a result of DNA recombination via natural transformation [1]. Foreign DNA acquired by HGT can be associated in bacteria with insertion sequence (IS) elements or tRNA genes and can be identified by an anomalous GC content or as a change of code usage [69]. The H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome harbours five IS elements, with two belonging to the IS200/IS605 family and three to the IS607 family according to the semi-automatic annotation system provided by the ISsaga tool [70]. Each IS element includes two genes, the orfA and orfB transposases. In addition, H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 contains 22 almost identical mini-IS elements of 232 bp with ~98% nucleotide identity uniformly distributed across the genome (Figure 1). The Mini-IS elements are vestigial remnants of full-length elements and have also been described in H. pylori [71,72]. Although it is not known if any of these elements have significant functional roles, the mini-ISs could be responsible for the alteration of the expression of some genes, and they may mediate HGT, thereby contributing to the genetic diversity among H. bizzozeronii strains.

Large inserts of laterally acquired DNA containing functionally related genes are often referred to as genomic islands (GIs) and are typically associated with an increased virulence [13]. The Island Viewer and Alien Hunter programs were able to identify a putative GI of ~70 kb (41 GC %) in the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome from base 1,559,252 to 1,628,818 (Figure 1). The GI is flanked by two IS elements and contains 77 CDSs (see additional file 1: Table S6) of which a putative function was assigned to 24 (31%). The H. bizzozeronii GI does not include the type IV secretion system or known virulence factors, and some genes, such as conjugal transfer protein (HBZC1_17110), replication A protein (HBZC1_17000) and the plasmid partitioning protein ParA (HBZC1_16910), appear originally have been plasmid-related features. These results suggest that a transposition event may have been responsible for the integration of a plasmid in the chromosome as already observed in C. jejuni [73] and in H. pylori [74].

A putative self-replicating circular plasmid pHBZ1, 52 kb in length, was sequenced from H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 (FR871758). Among the 21 genes for which a putative function was predicted (see additional file 1: Table S7), the plasmid contains the following elements: two copies of an aldo-keto reductase (HBZC1_p0200 and HBZC1_p0210), a complete type I restriction modification system (from HBZC1_p0340 to HBZC1_p0380), a protein containing the HipA-domain (HBZC1_p0540; [75]) and two copies of an adenine-specific methyltransferase (HBZC1_p0660 and HBZC1_p0680). The distribution of this plasmid among other H. bizzozeronii strains and its role in the adaption to the host and pathogenesis are unknown and merit further study.

Finally, immediately downstream of the H. bizzozeronii GI, a putative prophage region of about 37 kb was identified using Prophage Finder program [76] and it harbours several elements with homology to C. rectus RM3267 phage genes (Figure 1). However, excluding those involved in the phage replication, the majority of the genes included in the prophage region did not have any predictable function.

Conclusion

In this study, a detailed comparative genomic analysis between the human strain H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 and H. pylori showed important differences between these two human gastric pathogens, providing new insights into the comprehension of the biology of gastric Helicobacter species. Although H. bizzozeronii possesses all genes necessary for its specialized life in the stomach, it differs from H. pylori having a wider metabolic flexibility in term of energy sources and electron transport chain. Moreover, H. bizzozeronii genome harbours higher number of MCPs compared to H. pylori, allowing the bacterium to respond to a wider spectrum of environmental signals. The high metabolic flexibility in combination with extraordinary genome plasticity gives to H. bizzozeronii the ability to easily move through several environments and adapt to different hosts. This ability is probably a common feature among all the species belong to H. heilmannii s.l. since both H. felis and H. suis genomes harbours a similar repertoire of genes involved in metabolism and chemotaxis observed in H. bizzozeronii. Thus, is tempting to speculate that the zoonotic nature of H. heilmannii s.l. infection in humans is explicable by the high metabolic versatility of these species which probably supports the growth of the microorganisms in a wide range of niches.

Although H. bizzozeronii lacks orthologues of some major H. pylori virulence genes, other candidate virulence factors are present. In particular, we identify a polysaccharide lyase as a potential new virulence factor of H. bizzozeronii. Efforts are ongoing to define molecular methods for H. bizzozeronii in order to provide experimental evidence of the function of potential new virulence factors involved in the developing of human gastritis and MALT lymphoma.

Methods

Cultivation, growth conditions and DNA extraction

The human H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 strain was isolated in March 2008 from a 45-year-old Finnish female who was suffering from severe dyspeptic symptoms and for whom antrum and corpus biopsies revealed chronic active gastritis [8]. The strain was cultured on HP medium (LabM Limited, Lancashire, UK) containing 5% of bovine blood and Campylobacter selective supplement (Skirrow, Oxoid Ltd., Cambridge, UK) for 4 days at 37°C in an incubator with a microaerobic atmosphere of 10% CO2 and 5% O2 (Thermo Forma, Series II Water Jacketed Incubator; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA 02454 USA). The high molecular-weight genomic DNA of H. bizzozeronii was extracted as described before [8], and the genomic DNA for the Solexa 5 kb mate pair library was extracted using a ZR Fungal/Bacterial RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research Co, Irvine, CA, USA).

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome sequence of H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 was obtained as described previously [17]. Briefly, a combination of 454 Titanium (43x genome coverage, 8 kb mate pair library, performed by LGC Genomics GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and Solexa (50 cycles, 132x coverage, 5 kb mate pair library, performed by BaseClear BV, Leiden, The Netherlands) was assembled into 2 scaffolds representing a circular chromosome and a circular plasmid using the MIRA 3.2.1, SSAKE and the Staden software package. The assembly of the chromosome was validated by mapping to a MluI optical map produced by OpGen Inc. (Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA). The sequences were deposited in the EMBL bank under the accession numbers FR871757 and FR871758.

Annotation and comparative genomic

For gene finding and automatic annotation, the sequences were uploaded to the RAST server [77]. We further analysed the coding sequences using the Artemis tool [78] and manually re-annotated the genes of special interest. The homologues were identified using NCBI's BLAST suite of programs with NCBI nr and nt and Swissprot as reference databases. Two proteins with amino acid identity greater than 40% over 80% sequence length were considered homologues. The conserved functional domains in proteins were identified using the hmmer program on Pfam database [79] as well as the InterProScan [80]. For the prediction of glycosyltransferases, glycoside hydrolases, polysaccharide lyases and carbohydrate esterases, we referred to the annotation available in the CAZy database [48]. The metabolic pathways were reconstructed using KEGG and SEED as reference databases [77,81]. The subcellular locations of proteins were predicted using the PSORTb tool via the psort web server [82], and signal peptides were identified using SignalP [55], TatP [83] and LipoP [84].

To identify the proteins unique to H. bizzozeronii as well as the proteins found in H. pylori but missing in H. bizzozeronii, we determined the core genome of 10 H. pylori strains (J99, 26695, B8, HPAG1, B38, P12, G27, Shi470, SJM180 and PeCan4) using OrthoMCL with a BLAST E-value cut-off of 1.0 e-6 and an inflation parameter 1.5 [85]. We compared the core genome with the H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 genome, as previously described [86]. Briefly, based on the all-against-all BLASTp results, the proteins were clustered into groups of orthologues and recent paralogues. The proteins from H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 that did not cluster with any H. pylori proteins were considered to be specific to the species.

We identified the putative outer membrane proteins using BLASTp against the OMP database [87] and a set of known and categorised OMPs from H. pylori [42] using a BLASTp score ratio cut-off of 0.4 [88]. For further classification the resulting set of proteins was combined with the set of H. pylori OMPs and the phylogenetic relationships were analysed as described previously [13].

The H. bizzozeronii CIII-1 chromosome was searched for simple sequence repeats (SSRs) potentially involved in slipped-strand misparing using Msatfinder [89]. The thresholds for this study were as follows: mono (repeat unit length), > 8 (threshold value of repeat units); di > 5; tetra, penta, hexa and hepta, > 3. The positions of each of the SSRs (intergenic or intragenic) were identified using Artemis [78]. The lengths of all of the intragenic SSRs were artificially modified to assess the likely significance of the repeat-length variation on the expression of the associated reading frame.

The regions in the genome possibly acquired by horizontal gene transfer events as well as genomic islands were predicted using Alien Hunter [46] and Island Viewer [90], respectively. The potential prophage loci within the genome were predicted using the Prophage finder [76]. The possible IS elements were identified using the semi-automatic annotation system provided by ISsaga and were manually checked [70].

Abbreviations

ACC: acetophenone carboxylase; AHD: allophanate hydrolase; NRS: nitrite reductase system; SNO: S- and N- oxidases; FDH: formate reductase system; GDH: glycerol-3-phosphate deydrogenase; PL: polysaccharide lyase; HYD: hydrogenase; NDH: NAD(P)H dehydrogenase; SDH/FR: succinate dehydrogenase/fumarate reductase; MQR: malate-quinone-reductase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; GLC: glycol oxidase; NAP: periplasmic nitrate reductase; MCP: methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein; CAC: citric acid cycle; PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate; TMAO: trimethylamine-n-oxide; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide; OMP: outer membrane protein; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; GT: glycosyltransferase; Tat: twin-arginine secretion system; MMR: mismatch repair system; SSR: simple sequence repeat; HGT: horizontal gene transfer; IS: insertion sequence; GI: genomic island; s.l.: sensu lato; s.s.: sensu stricto.

Authors' contributions

TS performed the draft genome assembly and genome assembly validation and was responsible for the comparative genome analysis. PKK contributed to the data acquisition. MLH supervised the work at DFHEH. MR was responsible for the study design and coordination, contributed to the comparative genome analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Supplementary Material

supplementary tables. Table S1, Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein; Table S2, Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 CDS involved in metabolisms and respiration; Table S3, Outer Membrane Proteins of Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1; Table S4, Glycosyltransferases and genes involved in the biosynthesis of glycans in Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1; Table S5, ComB system in Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1; Table S6, List the CDS belonging to Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 genomic island; Table S7, List the CDS belonging to Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 plasmid pHBZ1.

Contributor Information

Thomas Schott, Email: thomas.schott@rub.de.

Pradeep K Kondadi, Email: pradeep.kondadi@helsinki.fi.

Marja-Liisa Hänninen, Email: marja-liisa.hanninen@helsinki.fi.

Mirko Rossi, Email: mirko.rossi@helsinki.fi.

Acknowledgements and Funding

This study was funded by the Academy of Finland (FCoE MiFoSa, no. 118602 and 141140) and the ERA-NET PathoGenoMics HELDIVNET project (SA 11957). MR was supported by an Academy of Finland Postdoctoral Fellowship (no. 132940). PKK was supported by a 2010 year grant from the Research Foundation of University of Helsinki and by a CIMO India Fellowship (25.11.2009/FM-09-6586).

References

- Suerbaum S, Josenhans C. Helicobacter pylori evolution and phenotypic diversification in a changing host. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(6):441–452. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F, Flahou B, Chiers K, Baele M, Meyns T, Decostere A, Ducatelle R. Gastric helicobacters in domestic animals and nonhuman primates and their significance for human health. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):202–23. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00041-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F, Flahou B, Smet A, Vandamme P, Ducatelle R. Non-Helicobacter pylori Helicobacter Species in the Human Gastric Mucosa: A Proposal to Introduce the Terms H. heilmannii Sensu Lato and Sensu Stricto. Helicobacter. 2011;16(4):339–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baele M, Pasmans F, Flahou B, Chiers K, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F. Non-Helicobacter pylori helicobacters detected in the stomach of humans comprise several naturally occurring Helicobacter species in animals. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;55(3):306–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meining A, Kroher G, Stolte M. Animal reservoirs in the transmission of Helicobacter heilmannii. Results of a questionnaire-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33(8):795–798. doi: 10.1080/00365529850171422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalava K, On SL, Harrington CS, Andersen LP, Hänninen ML, Vandamme P. A cultured strain of "Helicobacter heilmannii," a human gastric pathogen, identified as H. bizzozeronii: evidence for zoonotic potential of Helicobacter. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(6):1036–1038. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LP, Boye K, Blom J, Holck S, Norgaard A, Elsborg L. Characterization of a culturable "Gastrospirillum hominis" (Helicobacter heilmannii) strain isolated from human gastric mucosa. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(4):1069–1076. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1069-1076.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivistö R, Linros J, Rossi M, Rautelin H, Hänninen ML. Characterization of multiple Helicobacter bizzozeronii isolates from a Finnish patient with severe dyspeptic symptoms and chronic active gastritis. Helicobacter. 2010;15(1):58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hänninen ML, Happonen I, Saari S, Jalava K. Culture and characteristics of Helicobacter bizzozeronii, a new canine gastric Helicobacter sp. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46(1):160–166. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happonen I, Linden J, Saari S, Karjalainen M, Hänninen ML, Jalava K, Westermarck E. Detection and effects of helicobacters in healthy dogs and dogs with signs of gastritis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213(12):1767–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bock M, Decostere A, Van den Bulck K, Baele M, Duchateau L, Haesebrouck F, Ducatelle R. The inflammatory response in the mouse stomach to Helicobacter bizzozeronii, Helicobacter salomonis and two Helicobacter felis Strains. J Comp Pathol. 2005;133(2-3):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bock M, Decostere A, Hellemans A, Haesebrouck F, Ducatelle R. Helicobacter felis and Helicobacter bizzozeronii induce gastric parietal cell loss in Mongolian gerbils. Microbes Infect. 2006;8(2):503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole PW, Snelling WJ, Canchaya C, Forde BM, Hardie KR, Josenhans C, Graham RL, McMullan G, Parkhill J, Belda E, Bentley SD. Comparative genomics and proteomics of Helicobacter mustelae, an ulcerogenic and carcinogenic gastric pathogen. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger M, Baar C, Linz B, Raddatz G, Lanz C, Keller H, Morelli G, Gressmann H, Achtman M, Schuster SC. Who ate whom? Adaptive Helicobacter genomic changes that accompanied a host jump from early humans to large felines. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(7):e120.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermoote M, Vandekerckhove TT, Flahou B, Pasmans F, Smet A, De Groote D, Van Criekinge W, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F. Genome sequence of Helicobacter suis supports its role in gastric pathology. Vet Res. 2011;42(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold IC, Zigova Z, Holden M, Lawley TD, Rad R, Dougan G, Falkow S, Bentley SD, Muller A. Comparative whole genome sequence analysis of the carcinogenic bacterial model pathogen Helicobacter felis. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:302–308. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott T, Rossi M, Hanninen ML. Genome sequence of Helicobacter bizzozeronii strain CIII-1, an isolate from human gastric mucosa. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(17):4565–4566. doi: 10.1128/JB.05439-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs G, Weeks DL, Wen Y, Marcus EA, Scott DR, Melchers K. Acid acclimation by Helicobacter pylori. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:429–438. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury-Mone S, Mendz GL, Ball GE, Thibonnier M, Stingl K, Ecobichon C, Ave P, Huerre M, Labigne A, Thiberge JM, De Reuse H. Roles of alpha and beta carbonic anhydrases of Helicobacter pylori in the urease-dependent response to acidity and in colonization of the murine gastric mucosa. Infect Immun. 2008;76(2):497–509. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00993-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leduc D, Gallaud J, Stingl K, de Reuse H. Coupled amino acid deamidase-transport systems essential for Helicobacter pylori colonization. Infect Immun. 2010;78(6):2782–2792. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00149-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori T, Kanou N, Kusakabe S, Atomi H, Imanaka T. Allophanate hydrolase of Oleomonas sagaranensis involved in an ATP-dependent degradation pathway specific to urea. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;245(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G, Shapir N, Sadowsky MJ, Wackett LP. Allophanate hydrolase, not urease, functions in bacterial cyanuric acid metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(8):4437–4445. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4437-4445.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Prassl S, Haas R. Virulence mechanisms and persistence strategies of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;337:129–171. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-01846-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust M, Schweinitzer T, Josenhans C. In: Helicobacter pylori. Molecular genetics and cellular biology. Yamaoka Y, editor. Norwich: Caister Academic Press; 2008. Helicobacter flagella, motility and chemotaxis; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Szurmant H, Ordal GW. Diversity in chemotaxis mechanisms among the bacteria and archaea. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68(2):301–319. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.301-319.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness EF, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak HG, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald LM, Lee N, Adams MD, Hickey EK, Berg DE, Gocayne JD, Utterback TR, Peterson JD, Kelley JM, Cotton MD, Weidman JM, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes WS, Borodovsky M, Karp PD, Smith HO, Fraser CM, Venter JC. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388(6642):539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DJ. The physiology and metabolism of Campylobacter jejuni and Helicobacter pylori. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol. 2001. pp. 16S–24S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schilling CH, Covert MW, Famili I, Church GM, Edwards JS, Palsson BO. Genome-scale metabolic model of Helicobacter pylori 26695. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(16):4582–4593. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4582-4593.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig P, de Jonge BL, Alm RA, Brown ED, Uria-Nickelsen M, Noonan B, Mills SD, Tummino P, Carmel G, Guild BC, Moir DT, Vovis GF, Trust TJ. Helicobacter pylori physiology predicted from genomic comparison of two strains. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63(3):675–707. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.675-707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux MJ, Huang Y, Wang DN. Glycerol-3-phosphate transporter of Escherichia coli: structure, function and regulation. Res Microbiol. 2004;155(8):623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kather B, Stingl K, van der Rest ME, Altendorf K, Molenaar D. Another unusual type of citric acid cycle enzyme in Helicobacter pylori: the malate:quinone oxidoreductase. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(11):3204–3209. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.11.3204-3209.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horswill AR, Escalante-Semerena JC. In vitro conversion of propionate to pyruvate by Salmonella enterica enzymes: 2-methylcitrate dehydratase (PrpD) and aconitase Enzymes catalyze the conversion of 2-methylcitrate to 2-methylisocitrate. Biochemistry. 2001;40(15):4703–4713. doi: 10.1021/bi015503b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BL, Ruback S, Kiupakis AK, Kasbarian H, Pybus C, Reitzer L. The Escherichia coli gabDTPC operon: specific gamma-aminobutyrate catabolism and nonspecific induction. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(24):6976–6986. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.6976-6986.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalliri E, Mulrooney SB, Hausinger RP. Identification of Escherichia coli YgaF as an L-2-hydroxyglutarate oxidase. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(11):3793–3798. doi: 10.1128/JB.01977-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzner M, Germer J, Hengge R. Multiple stress signal integration in the regulation of the complex sigma S-dependent csiD-ygaF-gabDTP operon in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51(3):799–811. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]