Abstract

Background

Multicellular organisms regulate the uptake of calories, trace elements, and other nutrients by complex feedback mechanisms. In the case of iron, the body senses internal iron stores, iron requirements for hematopoiesis, and inflammatory status, and regulates iron uptake by modulating the uptake of dietary iron from the intestine. Both the liver and the intestine participate in the coordination of iron uptake and distribution in the body. The liver senses inflammatory signals and iron status of the organism and secretes a peptide hormone, hepcidin. Under high iron or inflammatory conditions hepcidin levels increase. Hepcidin binds to the iron transport protein, ferroportin (FPN), promoting FPN internalization and degradation. Decreased FPN levels reduce iron efflux out of intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages into the circulation. Derangements in iron metabolism result in either the abnormal accumulation of iron in the body, or in anemias. The identification of the mutations that cause the iron overload disease, hereditary hemochromatosis (HH), or iron-refractory iron-deficiencey anemia has revealed many of the proteins used to regulate iron uptake.

Scope of the review

In this review we discuss recent data concerning the regulation of iron homeostasis in the body by the liver and how transferrin receptor 2 (TfR2) affects this process.

Major conclusions

TfR2 plays a key role in regulating iron homeostasis in the body.

General significance

The regulation of iron homeostasis is important. One third of the people in the world are anemic. HH is the most common inherited disease in people of Northern European origin and can lead to severe health complications if left untreated.

Keywords: Hereditary hemochromatosis, transferrin receptor 2, TfR2, HFE, hepcidin, hemojuvelin, BMP, ferroportin

1. Iron homeostasis in the body

Iron is an essential nutrient required for a variety of biochemical processes such as respiration, metabolism, and DNA synthesis. Cells and organisms possess carefully regulated but poorly understood mechanisms for iron absorption and metabolism. Iron homeostasis in the body appears to be regulated primarily at the level of iron uptake through the intestine. Intestinal iron absorption is controlled by at least two kinds of regulators, those sensing iron stores in the body and those sensing the disparity between erythropoiesis and iron supply [1–6]. When the body is iron replete and under steady-state erythropoiesis, the intake of iron through the intestine is equal to the loss of iron through the urine, bleeding, and desquamation of intestinal tissue.

1.a. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron homeostasis

Hepcidin, a peptide synthesized by the liver and encoded by the gene, HAMP, plays a major role in iron homeostasis [7–11]. The mature form of the peptide is 20–25 amino acids with four disulfide bonds. The finding that Hamp knockout mice suffer from massive iron overload initially raised the possibility that hepcidin might be an iron stores regulator involved in communication of liver iron status to the intestine [9]. In patients with hepatic adenomas expressing high levels of hepcidin mRNA, the anemia was resolved upon the removal of the tumor or liver transplantation [12]. Similarly, mice that are engineered to overproduce hepcidin or injected with hepcidin are severely anemic [13–15]. These results indicate the importance of hepcidin in the regulation of iron uptake by the intestine.

The mechanism by which hepcidin regulates iron levels in the body is through its binding to ferroportin (FPN), the only known transporter for the efflux of iron out of cells and ultimately into the blood. The binding of hepcidin to FPN results in the internalization and degradation of both FPN and hepcidin [16]. Thus iron export from the intestine is decreased when the liver is stimulated to synthesize hepcidin.

1.b. Regulation of hepcidin mRNA

The discovery that hepcidin is a key regulator of iron homeostasis led to an intensive investigation of the control of hepcidin synthesis. Most of the studies concentrated on the induction or the suppression of hepcidin mRNA because mRNA levels are easy to measure and until recently, no antibodies or assays were sensitive enough to measure endogenous hepcidin in serum. Studies on the transcription of hepcidin show that it is regulated by both inflammation and iron and involves at least two or more interrelated signaling pathways (Figure 1).

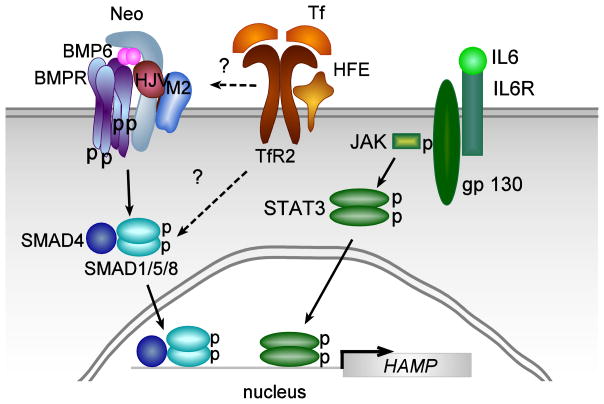

Figure 1. Model for the stimulation of hepcidin expression in hepatocytes by inflammation and by iron levels in the body.

Elevation of interleukin 6 (IL6) during inflammation stimulates hepcidin transcription through binding to the IL6-receptor (IL6R)-gp130 complex, which stimulates signaling through the phosphorylation of JAK leading to the phosphorylation of STAT3. The phosphorylated STAT3 dimer binds to two identified BMP responsive elements in the promoter region of hepcidin stimulating transcription. Elevation of iron levels in the body leads to the upregulation of BMP6 and Tf-saturation. BMP6 signals through binding to hemojuvelin (HJV), BMP receptors and neogenin (Neo) and signals through the SMAD4/SMAD1/5/8 pathway to stimulate hepcidin expression. Two BMP responsive elements in the promoter region of hepcidin have been identified. Less is known about the Tf-TfR2-HFE signaling pathway (see text). Mutations in HFE result in a blunted pSMAD response. The p38 MAPK-ERK1/2 signaling pathway is proposed to mediate this response.

Inflammatory processes increase interleukin 6 (IL6) and interleukin 1 (IL1), which activate HAMP expression through a JAK (just another kinase)-STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription)-mediated pathway [17–21]. The promoter region of hepcidin contains a STAT3 binding site [21]. Thus, stimulation of hepcidin expression through the inflammatory pathway, which results in decreased iron absorption and sequestration of iron in macrophages, provides an explanation of the anemia of chronic disease [12, 22].

Iron sensing by the liver is mediated through at least the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway involving BMPs, hemojuvelin (a co-receptor), matriptase-2 (a serine protease), BMP receptors, and the SMADs. BMP2, BMP4, and BMP6 are predominantly synthesized in the liver by endothelial and stellate cells, and to a lesser extent by hepatocytes [23, 24]. These BMPs bind to hemojuvelin and a subset of BMP type 1 receptors (ALK-2 and ALK-3) and BMP type 2 receptor (ActRIIA) [25]. Lack of functional hemojuvelin results in low levels of hepcidin mRNA, and severe iron-overload in patients and mice [26, 27]. Hemojuvelin, in turn, can be degraded by matriptase-2 cleavage [28]. Mutations in matriptase-2 fail to turn off hepcidin signaling, resulting in iron-refractory iron-deficiency anemia (IRIDA) [29–31]. Matriptase-2 mutations in a subset of patients with IRIDA have been identified [32–37]. Activation of the BMP receptors results in the phosphorylation of SMAD 1/5/8, which in conjunction with SMAD4 traffic to nucleus where they bind to BMP regulatory elements to activate hepcidin transcription [38–40]. In addition, neogenin binds to hemojuvelin and activates SMAD signaling, although this observation is controversial [25, 41–44]. Mice fed high iron diets show increased SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation [45, 46] implying that this pathway is sensitive to iron. Of the BMPs synthesized by the liver, BMP6 mRNA increases with iron loading, providing an iron-mediated regulation of hepcidin expression [47].

High iron diets also increase the iron-loading of Tf (Tf-saturation). Since lack of functional transferrin receptor 2 (TfR2) or the HH protein, HFE, also results in lower hepcidin mRNA levels and iron overload, these molecules also are involved in iron sensing. Signaling TfR2 is proposed to be through the activation of p38 MAPK/ERK (mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular-signal regulated kinase) [48, 49], but this is controversial. A study using an in vivo model of iron-overload failed to detect activation of the p38 MAPK/ERK pathway [50].

An intact SMAD signaling pathway appears to be necessary for Tf, STAT3 and p38 MAPK/ERK signaling [40]. Recent evidence indicates that an elevation in BMP6 is the result of chronic but not acute iron-loading and an elevation in Tf-saturation results from acute iron-loading [50, 51]. Increases in either BMP6 or Tf-saturation increase hepcidin mRNA. The inflammatory and p38 MAPK/ERK pathways are dependent on an intact SMAD signaling pathway. In the absence of SMAD4, high iron levels in the liver fail to induce hepcidin mRNA but do increase BMP6 levels [47]. Upregulation of hepcidin by inflammation requires intact BMP-regulatory elements in the hepcidin promoter [52, 53]. How the inflammatory, SMAD and p38 MAPK/ERK pathways are integrated remains to be resolved.

1.c. Erythropoietic regulators of iron uptake

The regulators for communicating the erythropoietic state of the individual are only beginning to be understood. Early physiological studies demonstrated that a soluble factor(s) in the blood is involved. Initially, iron-loaded Tf, ferritin, serum TfR1 generated from the proteolytic cleavage of the full-length transmembrane TfR1 were proposed as candidate factors [54–59]. Tf, ferritin, and TfR1 are found in serum and fluctuate with iron status of the individual. The amount of serum ferritin increases in iron-overloaded individuals. Although under most situations the concentration of Tf remains constant, Tf-saturation increases with iron overload. In addition to liver biopsy for iron-staining, ferritin levels and Tf-saturation are used clinically to evaluate iron stores in the body [60]. There are two notable exceptions to the correlation of these proteins with iron stores within an organism. Mice lacking or having very low levels of Tf suffer from iron overload [61], implying a possible role of Tf in the sensing of iron stores. This finding fits with the hypothesis that intestinal iron absorption is regulated according to Tf-saturation levels. In the absence of Tf, dietary iron is transported into the blood without regulation resulting in the severe iron-overload seen in the hypotransferrinemic mouse. The second exception is hyperferritinemic individuals. A mutation in the stem-loop structure of L-ferritin results in unregulated ferritin synthesis, leading to high serum ferritin levels and cataracts [62, 63]. Importantly, these people do not suffer from iron overload [63]). Thus, serum ferritin levels are not likely to be a key part of the sensing mechanism for iron absorption. Serum TfR1 fluctuates with erythropoietic activity and iron status of the organism [54]. Approximately 80% of serum TfR1 is generated from the maturation of erythroid cells [64]. One argument against a role for serum TfR1 as an erythroid regulatory factor is that it is generated after cells no longer need iron for hemoglobin biosynthesis.

Anemia also increases iron uptake by the intestine. Factors in the plasma of blood beside hepcidin are proposed to either act on the liver to suppress hepcidin transcription, thus allowing for greater iron uptake by the intestine by FPN or on the intestine to upregulate FPN. Several candidate molecules are proposed to regulate iron homeostasis during increased erythropoiesis. Thalassemias, which are characterized by defects in globin synthesis are used as a model to identify erythroid factors involved in the regulation of iron uptake. In this disorder, hepcidin levels are low [65, 66], which could account for the iron overload in thalassemic patients. Tanno and colleagues identified two genes with elevated mRNAs in murine models of thalassemias [67]. They include GDF15 (growth differentiation factor-15) and TWSG1 (twisted in gastrulation 1). GDF15 fulfills the criteria of a soluble factor, which regulates iron homeostasis. It is a member of the TNF-β family of proteins and in high concentrations can lower hepcidin mRNA. Further studies indicate that although GDF15 is elevated in a number of dyserythropoietic diseases, it is not elevated in normal blood donors who become anemic through the loss of blood [68]. TWSG1, also a member of the TGF-β1 family of cytokines, is capable of inhibiting hepcidin transcription and is elevated in thalassemic mice, murine hepatocytes and human cell lines [69]. The role of TWSG1 in normal iron homeostasis remains to be clarified.

1.d. Other roles of the liver in iron homeostasis

The liver plays a major role in iron homeostasis in the body in addition to secreting hepcidin. The Kupffer cells of the liver take up senescent red blood cells and hemoglobin through the hemoglobin-haptoglobin receptor (CD163), salvage the iron released from hemoglobin and secrete the iron as Fe2+ via FPN. Ceruloplasmin (Cp), a copper containing ferrioxidase, facilitates the efflux of iron from cells as well as the loading of iron into Tf [70–73]. Hepatocytes take up Tf through TfR1 and most likely through TfR2 [74]. They also take up other forms of non-Tf-bound iron, including heme via the heme-hemopexin receptor [75], and are capable of storing large quantities of iron in ferritin and hemosiderin, a breakdown product of ferritin. In addition to taking up and storing iron, hepatocytes synthesize Tf and Cp. Thus the liver and, in particular, the hepatocyte is thought to sense and reflect the bodily iron stores [76].

2. Hereditary hemochromatosis

Lack of proper communication regarding the amount of iron required by the body and intestinal iron uptake results in derangements in iron metabolism. In particular, hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is a disease of iron overload leading to iron accumulation in specific organs including the liver, heart, pancreas, and pituitary. Early studies demonstrated that intestinal iron absorption by HH patients is abnormally elevated [77]. Excess iron in affected tissues catalyzes oxidative damage, resulting in cirrhosis, hepatoma, cardiomyopathy, diabetes, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and arthritis [60].

The most prevalent form of HH results from a point mutations in HFE. HH causing mutations in HFE result in autosomal recessive form of HH type 1. The HFE (C282Y) is the most common inherited disease in Caucasians (reviewed in [78]). The carrier frequency is about 1 in 9 in people of Northern European origin in the U.S., and the disease affects approximately 1 in 400–10,000 individuals. In a North American screen of ~10,000 participants the prevalence of HFE(C282Y) homozygotes in non-Hispanic whites was 0.44% with other ethnic groups lower [79]. While carrying this mutation may be an advantage with an iron-poor diet, it presents a distinct disadvantage for an iron-sufficient diet. The frequency and importance of HH has only recently been appreciated because it was difficult to diagnose prior to PCR technology and identification of the point mutation in HFE responsible for the most common form of HH.

Other forms of HH arise from mutations in hepcidin, hemojuvelin, TfR2, and FPN [9, 80–83]. Mutations in hepcidin and hemojuvelin result in juvenile hemochromatosis, the most severe form of HH (HH type 2A and 2B respectively). The pathological symptoms of iron-overload are apparent as early as the second and third decade of life. In contrast mutations in HFE (HH type 1) results in a milder form of iron overload usually apparent in the fifth to sixth decade of life. Mutations in TfR2 (HH type 3) are rare and result in mild to intermediate iron-overload. HH types 1–3 result in primary iron loading in the hepatocytes, implying a key role for this cell type in iron homeostasis. Mutations in FPN (HH type 4A & 4B) lead to autosomal dominant diseases with different phenotypes depending on the particular mutation (reviewed in [84, 85]. Mutations in FPN that fail to fold properly or transport iron are dominant-negative mutations. The HH type 4A mutations result in low Tf-saturation and iron accumulation in liver macrophages rather than hepatocytes. The flatiron mouse mutation, arising from an ethylnitrosurea-induced mutagenesis screen, is a mouse model of HH type 4A [86]. Dominant positive mutations in FPN, include mutations that can still transport iron but fail to bind hepcidin or that are not downregulated in response to binding hepcidin (HH type 4B). Patients with HH type 4B have high Tf-saturation and high levels of iron in hepatocytes similar to HH types 1–3.

3. Identification of transferrin receptor 2

In most tissues, TfR1 is responsible for the majority of cellular iron uptake through interaction with iron-bound Tf [87]. This homodimeric membrane receptor binds two molecules of iron-loaded Tf with high affinity and is internalized into acidified endosomes. The combination of TfR1 and low pH facilitates the release of iron from Tf [88, 89]. The iron is then transported across the vesicle membrane for utilization within the cell and/or storage. The TfR1-Tf complex recycles back to the cell surface where apo-Tf is released at the higher pH in extracellular space of tissues. Although TfR1-mediated endocytosis is the major pathway for cellular iron uptake, cells can obtain iron through TfR1 independent pathways using diferric Tf or inorganic iron (reviewed by Aisen and colleagues [87]).

The more recently identified TfR2 is a second, distinct TfR and could be responsible for the non-TfR1 mediated uptake of Tf into the liver as reported earlier. TfR2 clearly plays a critical role in iron homeostasis, because mutations in TfR2 result in a rare form of HH [90]. TfR2 can support growth in transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells lacking endogenous Tf receptors, given Tf as an iron source [74]. The role of TfR2 in Tf-mediated iron-uptake by the liver has been called into doubt recently [91]. These studies only found a minimal contribution of TfR2-mediated iron uptake in a hepatoma cell line, HUH7 cells. Both people and mice with mutations in TfR2 or lacking TfR2 suffer from iron-overload in the liver [92, 93]. These findings indicate that the uptake of iron into the liver by TfR2 is not the primary function for this receptor and that TfR2 may have additional functions. The expression of both hepcidin and TfR2 in hepatocytes [92, 94, 95] and the observation that TfR2 is regulated by iron-loaded Tf, led to the hypothesis that TfR2 might sense the levels of Tf-saturation in the blood [96]. TfR2 would then activate hepcidin transcription, in addition to its ability to take up Tf (Figure 1).

4. Distinguishing features of transferrin receptor 1 and 2

TfR2, like TfR1, is a type II membrane glycoprotein with a large C-terminal ectodomain and small N-terminal cytoplasmic domain [97, 98]. TfR2 shares 45% amino acid sequence identity with TfR1 in the extracellular region, has two cysteines in the ectodomain proximal to the transmembrane domain that form intersubunit disulfide bonds like TfR1, and has an internalization sequence in its cytoplasmic domain [97, 98].

Clear differences exist in the regulation of the two TfRs. In humans and mice, TfR2 is expressed predominantly in liver, erythroid precursors [99, 100], and also expressed in erythroid cell lines [100], while TfR1 is expressed ubiquitously [93, 98]. Intracellular iron controls TfR1 mRNA stability. In contrast changes in intracellular iron levels do not influence the level of TfR2 mRNA [96–98, 101]. TfR2 expression is controlled at the transcriptional level by the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 [100]. The transcriptional regulation of TfR2 in the liver has not been characterized extensively. Tfr2 mRNA levels increase dramatically from embryonic day 13 to postnatal day 4 in the developing mouse liver [102]. The transcription factor C/EBP-α is abundant in the liver and induces transcription in Tfr2 promoter reporter assays [102].

The two receptors are functionally different. Although TfR2 can mediate cellular iron-uptake in transfected cells, TfR2 is not sufficient to compensate for the function of TfR1 because mice in which Tfr1 is deleted die as embryos [103]. The lack of ability for TfR2 to compensate for TfR1 could be due to its restricted expression pattern. The affinity of TfR2 for iron-loaded Tf is 27 nM, 27 fold lower than TfR1 [98, 104, 105]. A lower affinity of Tf could make TfR2 more sensitive to Tf-saturations in the blood, although the binding constants measured in vitro are still too high to be sensitive to Tf-saturation. While both receptors have internalization motifs, there are no sequence similarities in their respective cytoplasmic domains. Evidence suggests that the two receptors can internalize by independent mechanisms [106]. Both TfR1 and TfR2 bind to HFE and Tf, but the interacting domains of HFE with TfR2 are different from those with TfR1. The crystal structure of the ectodomains of TfR1 and HFE indicates that TfR1 interacts with α1 and α2 domains of HFE [107]. Extensive site-directed mutagenesis studies indicate that the binding site of HFE on TfR1 substantially overlaps with that of Tf-binding site [108, 109]. In contrast, co-precipitation studies using cell lines transfected with TfR2 and HFE chimeras indicates that TfR2 interacts with α3 domain of HFE and the binding of HFE to TfR2 does not interfere with Tf binding [110]. HFE interacts with the extracellular domain of TfR2 proximal to the transmembrane domain (TfR2 residues 104–250) [110, 111]. The TfR2-HFE complex in the liver regulates hepcidin expression [112, 113].

5. Mutations in transferrin receptor 2 result in hereditary hemochromatosis

The role of TfR2 in a rare form of HH was initially surprising because northern analysis of TfR2 mRNA tissue distribution indicated that TfR2 is predominantly expressed in the liver [97, 98] and early erythroid precursors [99, 100]. One report using antibodies to TfR2 indicates that TfR2 is located extensively throughout the intestine [114] and another report shows TfR2 in the crypt cells of the intestine [115]. Both used immunohistological staining. These reports are inconsistent with the lack of TfR2 mRNA in the intestine [97, 98].

The mutations in TfR2 associated with HH are all recessive. They fall into three categories: amino acid deletions, single amino acid substitutions, and nonsense mutations producing a truncated protein. The most severe mutation results in a transcript encoding the first 63 residues of TfR2. An interesting disease-causing mutation in TfR2 is a single aminoacid substitution of a valine to isoleucine in the cytoplasmic domain (V22I) [116]. Most mutations of the cytoplasmic domain of proteins disrupt signaling or trafficking rather than ligand-binding. The recessive nature of the disease combined with extreme truncation of the resultant protein product is consistent with a loss of function rather than a gain of function. The generation of the Tfr2 knockout mouse model confirms this prediction [92]. Mice with a complete or liver-specific knockout of Tfr2 have no detectable Tfr2 protein in their livers and develop significant liver iron-overload and elevated Tf-saturation [117, 118]. The iron overload in the hepatocyte-specific knockout mouse and the Tfr2 knockout mice are similar to the phenotype of the most common mutation (245X) in TfR2-associated HH demonstrating that mutations in TfR2 causing HH are due to lack of functional protein [92, 117]. All result in lower hepcidin expression compared to wild-type mice with equivalent liver-iron loading. Conversely, the hepatocyte-specific expression of Tfr2 in TfR2-deficient mice increases hepcidin expression and decreases hepatic iron levels and Tf-saturation [112]. Collectively, these results demonstrate that lack of expression of TfR2 in hepatocytes accounts for the increased iron absorption and iron accumulation in the liver seen in this form of hemochromatosis.

6. Regulation of transferrin receptor 2 in the liver

Several studies shed some light on the regulation of TfR2 in the liver [96, 101, 104]. Two studies demonstrate stabilization of TfR2 by iron-loaded Tf [96, 101]. Western blot analysis shows that TfR2 increases in a time- and dose- dependent manner after addition of iron-loaded Tf to the culture medium [96]. In cells exposed to iron-loaded Tf, the amount of TfR2 returns to control levels within 8 hours after removal of iron-loaded Tf from the medium indicating a higher turnover rate than TfR1 [96]. However, TfR2 does not increase when non-Tf bound iron (FeNTA) or apo-Tf is added to the medium [96], which suggests that the Tf binding stabilizes TfR2 [96]. The response to iron-loaded Tf appears to be hepatocyte specific. Non-hepatic cell lines which either endogenously express TfR2 such as K562 cells or are transfected with a plasmid coding for TfR2 do not show a similar response [96, 101]. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis shows that TfR2 mRNA levels do not change in cells exposed to iron-loaded Tf [96, 101]. Rather, the increase in TfR2 is due to an increase in the half-life at the protein level in cells exposed to iron-loaded Tf [96]. The binding of Tf to TfR2 and the cytoplasmic domain of TfR2 appear to be largely responsible for the stabilization of TfR2 by Tf [119, 120]. TfR2 levels increased in response to Tf while TfR1 levels were downregulated over 10 fold [96]. These results support a role for TfR2 in monitoring iron levels by sensing changes in the concentration of iron-loaded Tf.

Animal studies are consistent with the stabilization of TfR2 by iron-loaded Tf rather than iron loading of hepatocytes. The Hfe-deficient and hypotransferrinemic mice both have iron-overloaded livers [101]. Rats fed an iron-deficient diet have lower TfR2 levels than rats fed a high iron diet [101]. Tfr2 is higher in Hfe knockout mice compared to wild-type littermates [101]. Conversely, hypotransferrinemic mice have extremely low levels of Tf and reduced Tfr2 supporting the role of iron-loaded Tf in the regulation of Tfr2 [101]. The regulation of Tfr2 in these mice is consistent with tissue culture studies showing that intracellular iron-levels do not correlate with TfR2 levels. Rather, regulation of TfR2 does correlate with the levels of Tf-saturation in the serum or cell culture medium. Because both the tissue culture and the animal studies show that TfR2 levels are sensitive to Tf over a physiological range of Tf-saturation in the blood, TfR2 is proposed to be part of the iron-sensing machinery in the liver for bodily iron levels as reflected by Tf-saturation. Consistent with this hypothesis, mice with a disease-causing mutation in Tfr2 have decreased hepcidin mRNA levels [104], and hepcidin mRNA in Tfr2 mutant mice is decreased relative to their liver iron levels.

7. The role of transferrin receptor 2 in iron homeostasis

The lack of functional TfR2 or HFE results in HH. TfR2 and HFE interact [110, 111]. Further studies demonstrate that TfR2 forms a complex with iron-loaded Tf and HFE to regulate hepcidin expression in hepatoma cell lines stably expressing HFE, and in primary hepatocytes [113]. In mice, both Tfr2 and Hfe are required for the proper regulation of hepcidin expression in vivo. Hfe but not Tfr2 is limiting in the formation of the Hfe/Tfr2 complex to regulate hepcidin expression [112]. In addition, one recent study shows that TfR2 is critical for iron-sensing and hepcidin regulation in human primary hepatocytes [121], and another study using patients with HFE and TfR2 hemochromatosis indicates that TfR2 plays a prominent and HFE plays a contributory role in the regulation of hepcidin in response to a dose of oral iron [122]. These observations suggest that HFE and TfR2 are part of an upstream pathway that regulates hepcidin expression, and supports a model proposed by Schmidt et al. [123] in which TfR1 serves to sequester HFE from interaction with TfR2, thereby reducing signaling for hepcidin expression. When the Tf-saturation increases, iron-loaded Tf competes with HFE to bind to TfR1, which releases HFE from binding to TfR1 and allows HFE to bind to TfR2, thereby Tf-TfR2-HFE complex forms and initiates regulation of hepcidin expression (Figure 2).

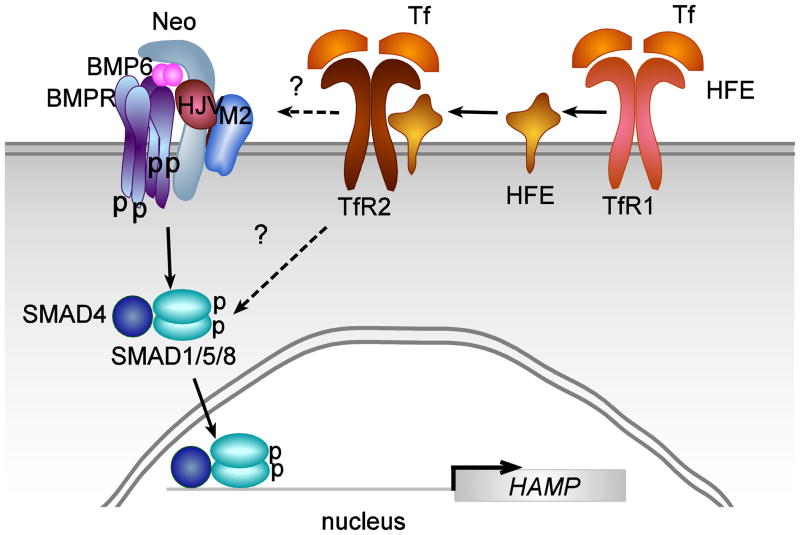

Figure 2. Model for the function of HFE and TfR2 in hepcidin signaling.

Upon Tf binding to transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), HFE is released and binds to transferrin receptor 2 (TfR2). The HFE-TfR2 complex stimulates SMAD signaling either directly by binding to the BMPR receptor complex or indirectly, through stimulating a MAPK-ERK complex that stimulates SMAD phosphorylation.

The mechanism by which the TfR2/HFE complex regulates hepcidin expression remains to be determined. Studies in humans with mutations in HFE show that the regulation of hepcidin is blunted. Hepcidin is still modulated by iron stores both in patients and in Hfe knockout mice [124, 125]. Mice lacking functional Hfe with overexpression of Tfr2 still have lower hepcidin levels indicating that elevated TfR2 levels cannot compensate for lack of HFE [112]. Tfr2 knockout mice have a more severe iron overload phenotype than Hfe knockout mice [126] indicating that TfR2 may have additional functions in the regulation of iron homeostasis. Mice with combined deletions of both Tfr2 and Hfe display a more severe iron overload phenotype compared to Hfe knockout mice or to Tfr2 knockout mice [126]. These results are consistent with a more severe form of iron overload in a report of a patient with mutations in both TFR2 and HFE [127].

The BMP/SMAD signaling pathway plays an important role in the regulation of hepcidin expression [45, 128]. BMP6 is an endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression [129, 130]. HFE is not necessary for regulation of BMP6 in response to iron, but HFE-deficiency triggers iron overload by decreasing hepatic BMP/SMAD signaling [131], and impairing downstream signals of BMP6 triggered by iron [132]. Both Tfr2-deficient and Hfe-deficient mice have similar pSMAD levels as the wild type mice, but Tfr2 and Hfe double knockout mice have lower phospho-SMAD levels, and all of them have lower phospho-ERK1/2 levels [126], indicating that the p38MAPK/ERK1/2 and SMAD signaling pathways could be involved in the regulation of hepcidin by TfR2 and HFE. Further in vitro studies support this hypothesis. Ramey and colleagues showed that iron-loaded Tf, in cooperation with circulating serum factors, stimulates hepcidin expression through both the p38MAPK/ERK1/2 and BMP/hemojuvelin (HJV) pathways [133]. Poli and colleagues show that iron-loaded Tf in a complex with TfR2 and HFE induce furin expression and the p38MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Furin participates maturation of hepcidin and thereby regulates hepcidin expression [49]. Taken together, these studies indicate that TfR2 may regulate hepcidin expression through the p38MAPK/ERK and BMP/SMAD signaling pathways. No p38MAPK/ERK activation was detected in mouse models of acute and chronic iron-loading leaving the role of p38MAPK/ERK signaling controversial [50].

8. The role of transferrin receptor 2 in erythropoiesis

TfR2 is predominantly expressed in hepatocytes, but is also expressed in human erythroid progenitors, erythroblasts [99, 134], UT7 (erythroleukemia) cells [135], and K562 (erythro-myeloblastoid leukemia) cells [96, 98]. The role of TfR2 in immature erythroid cells is largely unexplored because no significant changes in hematopoietic parameters of peripheral blood were originally detected between wild type and Tfr2 deficient mice [93]. A genome-wide association study shows that a TfR2 polymorphism is associated with red blood cell (RBC) hematocrit and mean corpuscular volume [136]. In addition, a recent study demonstrates that TfR2 binds to erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) and is required for efficient erythropoiesis [135]. TfR2 and EpoR are co-expressed during the differentiation of erythroid progenitors. EpoR associates with TfR2 in the endoplasmic reticulum and TfR2 is required for the efficient transport of EpoR to the cell surface [135]. Erythroid progenitors from Tfr2-deficient mice are less sensitive to erythropoietin (Epo), which are presumably compensated by increased circulating Epo levels in their serum. Epo/EpoR is required for survival and proliferation of erythroid progenitors and their terminal differentiation [137–139]. These studies underscore the involvement of TfR2 in erythropoiesis.

Erythropoiesis is the most iron-consuming process in mammals. TfR2 is one of the key regulators of iron homeostasis because it modulates hepcidin expression in the liver. Under physiological conditions, about 25 mg of iron/day (~70% of total iron) are used for hemoglobin biosynthesis. The recycling of hemoglobin iron from senescent erythrocytes by liver and spleen macrophages serves as the major iron source for erythropoiesis. Interestingly, hepcidin production is suppressed by increased erythropoiesis in the bone marrow, which allows more hemoglobin synthesis by increasing iron uptake from the intestine and iron release from the macrophage. The crosstalk between iron homeostasis and erythropoiesis, the role of Tfr2 in erythropoiesis in vivo and the mechanism by which TfR2 regulates erythropoiesis remain to be determined.

9.Future directions

In spite of the rapid progress made towards the understanding of iron homeostasis in the past 10 years key issues remain to be resolved.

How does the TfR2-HFE complex stimulate hepcidin transcription? Does the TfR2-HFE complex directly interact with the BMPR signaling complex or indirectly regulate the levels of pSMAD? Stimulation of the p38MAPK/ERK1/2 pathway is the prime candidate for the downstream signaling by TfR2/HFE complex. How is this accomplished?

How does BMP6 respond to iron? BMP6 levels positively correlate with iron levels in the liver. How do liver iron levels control BMP6 expression?

How does erythropoiesis regulate iron uptake? Is it having direct or indirect effects on the liver suppressing hepcidin levels?

What is the role of TfR2 in regulating erythropoiesis?

What pathways can be exploited to treat iron overload and iron refractory anemias? Hepcidin, HFE, TfR2, HJV all appear to be specific targets to regulate iron homeostasis. How can these molecules be targeted or regulated to normalize iron levels in disease states?

Highlights.

Recent data concerning the regulation of iron homeostasis in the body by the liver is discussed.

Transferrin receptor 2 plays a distinct role in the regulation of hepcidin.

Transferrin receptor 2 is controlled both transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally at the level of protein stability.

Transferrin receptor 2 also plays a role in erythropoiesis.

The regulation of hepcidin transcription is controlled by both iron through Tf saturation and BMP6 and by inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH DK072166 (CAE) and an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (JC)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Finch C. Regulators of iron balance in humans. Blood. 1994;84:1697–1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin MW, McCarthy DM, Garry PJ. Evidence that iron stores regulate iron absorption--a setpoint theory. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:1376–1380. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.6.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt JR, Roughead ZK. Adaptation of iron absorption in men consuming diets with high or low iron bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:94–102. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathanson MH, Muir A, McLaren GD. Iron absorption in normal and iron-deficient beagle dogs: mucosal iron kinetics. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:G439–448. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1985.249.4.G439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayers MH, English G, Finch C. Capacity of the store-regulator in maintaining iron balance. Amer J Hematol. 1994;47:194–197. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830470309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skikne BS, Cook JD. Effect of enhanced erythropoiesis on iron absorption. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:746–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming RE, Sly WS. Hepcidin: A putative iron-regulatory hormone relevant to hereditary hemochromatosis and the anemia of chronic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8160–8162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161296298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krause A, Neitz S, Magert HJ, Schulz A, Forssmann WG, Schulz-Knappe P, Adermann K. LEAP-1, a novel highly disulfide-bonded human peptide, exhibits antimicrobial activity. FEBS Lett. 2000;480:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01920-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolas G, Bennoun M, Devaux I, Beaumont C, Grandchamp B, Kahn A, Vaulont S. Lack of hepcidin gene expression and severe tissue iron overload in upstream stimulatory factor 2 (USF2) knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8780–8785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151179498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pigeon C, Ilyin G, Courselaud B, Leroyer P, Turlin B, Brissot P, Loreal O. A new mouse liver-specific gene, encoding a protein homologous to human antimicrobial peptide hepcidin, is overexpressed during iron overload. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7811–7819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park CH, Valore EV, Waring AJ, Ganz T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7806–7810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein DA, Roy CN, Fleming MD, Loda MF, Wolfsdorf JI, Andrews NC. Inappropriate expression of hepcidin is associated with iron refractory anemia: implications for the anemia of chronic disease. Blood. 2002;100:3776–3781. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viatte L, Nicolas G, Lou DQ, Bennoun M, Lesbordes-Brion JC, Canonne-Hergaux F, Schonig K, Bujard H, Kahn A, Andrews NC, Vaulont S. Chronic hepcidin induction causes hyposideremia and alters the pattern of cellular iron accumulation in hemochromatotic mice. Blood. 2006;107:2952–2958. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy CN, Mak HH, Akpan I, Losyev G, Zurakowski D, Andrews NC. Hepcidin antimicrobial peptide transgenic mice exhibit features of the anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2007;109:4038–4044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivera S, Liu L, Nemeth E, Gabayan V, Sorensen OE, Ganz T. Hepcidin excess induces the sequestration of iron and exacerbates tumor-associated anemia. Blood. 2005;105:1797–1802. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn MB, Donovan A, Ward DM, Ganz T, Kaplan J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306:2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verga Falzacappa MV, Vujic Spasic M, Kessler R, Stolte J, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU. STAT3 mediates hepatic hepcidin expression and its inflammatory stimulation. Blood. 2007;109:353–358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inamura J, Ikuta K, Jimbo J, Shindo M, Sato K, Torimoto Y, Kohgo Y. Upregulation of hepcidin by interleukin-1beta in human hepatoma cell lines. Hepatol Res. 2005;33:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee P, Peng H, Gelbart T, Wang L, Beutler E. Regulation of hepcidin transcription by interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1906–1910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409808102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pietrangelo A, Dierssen U, Valli L, Garuti C, Rump A, Corradini E, Ernst M, Klein C, Trautwein C. STAT3 is required for IL-6-gp130-dependent activation of hepcidin in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:294–300. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood. 2006;108:3204–3209. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolas G, Chauvet C, Viatte L, Danan JL, Bigard X, Devaux I, Beaumont C, Kahn A, Vaulont S. The gene encoding the iron regulatory peptide hepcidin is regulated by anemia, hypoxia, and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1037–1044. doi: 10.1172/JCI15686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang AS, Gao J, Koeberl DD, Enns CA. The role of hepatocyte hemojuvelin in the regulation of bone morphogenic protein-6 and hepcidin expression in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16416–16423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knittel T, Fellmer P, Muller L, Ramadori G. Bone morphogenetic protein-6 is expressed in nonparenchymal liver cells and upregulated by transforming growth factor-beta 1. Exp Cell Res. 1997;232:263–269. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia Y, Babitt JL, Sidis Y, Chung RT, Lin HY. Hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression via a selective subset of BMP ligands and receptors independently of neogenin. Blood. 2008;111:5195–5204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papanikolaou G, Samuels ME, Ludwig EH, MacDonald ML, Franchini PL, Dube MP, Andres L, MacFarlane J, Sakellaropoulos N, Politou M, Nemeth E, Thompson J, Risler JK, Zaborowska C, Babakaiff R, Radomski CC, Pape TD, Davidas O, Christakis J, Brissot P, Lockitch G, Ganz T, Hayden MR, Goldberg YP. Mutations in HFE2 cause iron overload in chromosome 1q-linked juvenile hemochromatosis. Nature Genet. 2004;36:77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niederkofler V, Salie R, Arber S. Hemojuvelin is essential for dietary iron sensing, and its mutation leads to severe iron overload. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2180–2186. doi: 10.1172/JCI25683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvestri L, Pagani A, Nai A, De Domenico I, Kaplan J, Camaschella C. The serine protease matriptase-2 (TMPRSS6) inhibits hepcidin activation by cleaving membrane hemojuvelin. Cell Metab. 2008;8:502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du X, She E, Gelbart T, Truksa J, Lee P, Xia Y, Khovananth K, Mudd S, Mann N, Moresco EM, Beutler E, Beutler B. The serine protease TMPRSS6 is required to sense iron deficiency. Science. 2008;320:1088–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1157121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folgueras AR, de Lara FM, Pendas AM, Garabaya C, Rodriguez F, Astudillo A, Bernal T, Cabanillas R, Lopez-Otin C, Velasco G. Membrane-bound serine protease matriptase-2 (Tmprss6) is an essential regulator of iron homeostasis. Blood. 2008;112:2539–2545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finberg KE, Heeney MM, Campagna DR, Aydinok Y, Pearson HA, Hartman KR, Mayo MM, Samuel SM, Strouse JJ, Markianos K, Andrews NC, Fleming MD. Mutations in TMPRSS6 cause iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) Nature Genet. 2008;40:569–571. doi: 10.1038/ng.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsay AJ, Quesada V, Sanchez M, Garabaya C, Sarda MP, Baiget M, Remacha A, Velasco G, Lopez-Otin C. Matriptase-2 mutations in iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia patients provide new insights into protease activation mechanisms. Human Mol Genet. 2009;18:3673–3683. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tchou I, Diepold M, Pilotto PA, Swinkels D, Neerman-Arbez M, Beris P. Haematologic data, iron parameters and molecular findings in two new cases of iron-refractory iron deficiency anaemia. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83:595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beutler E, Van Geet C, te Loo DM, Gelbart T, Crain K, Truksa J, Lee PL. Polymorphisms and mutations of human TMPRSS6 in iron deficiency anemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010;44:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi HS, Yang HR, Song SH, Seo JY, Lee KO, Kim HJ. A novel mutation Gly603Arg of TMPRSS6 in a Korean female with iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pbc.23190. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Falco L, Totaro F, Nai A, Pagani A, Girelli D, Silvestri L, Piscopo C, Campostrini N, Dufour C, Al Manjomi F, Minkov M, Van Vuurden DG, Feliu A, Kattamis A, Camaschella C, Iolascon A. Novel TMPRSS6 mutations associated with iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) Hum Mutat. 2010;31:E1390–1405. doi: 10.1002/humu.21243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silvestri L, Guillem F, Pagani A, Nai A, Oudin C, Silva M, Toutain F, Kannengiesser C, Beaumont C, Camaschella C, Grandchamp B. Molecular mechanisms of the defective hepcidin inhibition in TMPRSS6 mutations associated with iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia. Blood. 2009;113:5605–5608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Truksa J, Lee P, Beutler E. Two BMP responsive elements, STAT, and bZIP/HNF4/COUP motifs of the hepcidin promoter are critical for BMP, SMAD1, and HJV responsiveness. Blood. 2009;113:688–695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verga Falzacappa MV, Casanovas G, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU. A bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-responsive element in the hepcidin promoter controls HFE2-mediated hepatic hepcidin expression and its response to IL-6 in cultured cells. J Mol Med. 2008;86:531–540. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang RH, Li C, Xu X, Zheng Y, Xiao C, Zerfas P, Cooperman S, Eckhaus M, Rouault T, Mishra L, Deng CX. A role of SMAD4 in iron metabolism through the positive regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2005;2:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang AS, Anderson SA, Meyers KR, Hernandez C, Eisenstein RS, Enns CA. Evidence that inhibition of hemojuvelin shedding in response to iron is mediated through neogenin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12547–12556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang AS, Yang F, Meyer K, Hernandez C, Chapman-Arvedson T, Bjorkman PJ, Enns CA. Neogenin-mediated hemojuvelin shedding occurs after hemojuvelin traffics to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17494–17502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710527200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang AS, Yang F, Wang J, Tsukamoto H, Enns CA. Hemojuvelin-neogenin interaction is required for bone morphogenic protein-4-induced hepcidin expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22580–22589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee DH, Zhou LJ, Zhou Z, Xie JX, Jung JU, Liu Y, Xi CX, Mei L, Xiong WC. Neogenin inhibits HJV secretion and regulates BMP-induced hepcidin expression and iron homeostasis. Blood. 2010;115:3136–3145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Wrighting DM, Xia Y, Sidis Y, Samad TA, Campagna JA, Chung RT, Schneyer AL, Woolf CJ, Andrews NC, Lin HY. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nature Genet. 2006;38:531–539. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin L, Valore EV, Nemeth E, Goodnough JB, Gabayan V, Ganz T. Iron-transferrin regulates hepcidin synthesis in primary hepatocyte culture through hemojuvelin and BMP2/4. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kautz L, Meynard D, Monnier A, Darnaud V, Bouvet R, Wang RH, Deng C, Vaulont S, Mosser J, Coppin H, Roth MP. Iron regulates phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 and gene expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 in the mouse liver. Blood. 2008;112:1503–1509. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calzolari A, Raggi C, Deaglio S, Sposi NM, Stafsnes M, Fecchi K, Parolini I, Malavasi F, Peschle C, Sargiacomo M, Testa U. TfR2 localizes in lipid raft domains and is released in exosomes to activate signal transduction along the MAPK pathway. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4486–4498. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poli M, Luscieti S, Gandini V, Maccarinelli F, Finazzi D, Silvestri L, Roetto A, Arosio P. Transferrin receptor 2 and HFE regulate furin expression via mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/Erk) signaling. Implications for transferrin-dependent hepcidin regulation. Haematologica. 2010;95:1832–1840. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.027003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corradini E, Meynard D, Wu Q, Chen S, Ventura P, Pietrangelo A, Babitt JL. Serum and liver iron differently regulate the bone morphogenetic protein 6 (BMP6)-SMAD signaling pathway in mice. Hepatology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hep.24359. e-pub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramos E, Kautz L, Rodriguez R, Hansen M, Gabayan V, Ginzburg Y, Roth MP, Nemeth E, Ganz T. Evidence for distinct pathways of hepcidin regulation by acute and chronic iron loading in mice. Hepatology. 2011;53:1333–1341. doi: 10.1002/hep.24178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casanovas G, Mleczko-Sanecka K, Altamura S, Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-responsive elements located in the proximal and distal hepcidin promoter are critical for its response to HJV/BMP/SMAD. J Mol Med. 2009;87471-80:471–480. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinbicker AU, Sachidanandan C, Vonner AJ, Yusuf RZ, Deng DY, Lai CS, Rauwerdink KM, Winn JC, Saez B, Cook CM, Szekely BA, Roy CN, Seehra JS, Cuny GD, Scadden DT, Peterson RT, Bloch KD, Yu PB. Inhibition of bone morphogenetic protein signaling attenuates anemia associated with inflammation. Blood. 2011:e-pub. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cazzola M, Beguin Y, Bergamaschi G, Guarnone R, Cerani P, Barella S, Cao A, Galanello R. Soluble transferrin receptor as a potential determinant of iron loading in congenital anaemias due to ineffective erythropoiesis. Brit J Haematol. 1999;106:752–755. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook JD, Dassenko S, Skikne BS. Serum transferrin receptor as an index of iron absorption. Brit J Haematol. 1990;75:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1990.tb07806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feelders RA, Kuiper-Kramer EP, van Eijk HG. Structure, function and clinical significance of transferrin receptors. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:1–10. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flowers CA, Kuizon M, Beard JL, Skikne BS, Covell AM, Cook JD. A serum ferritin assay for prevalence studies of iron deficiency. Amer J Hematol. 1986;23:141–151. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830230209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raja KB, Pountney DJ, Simpson RJ, Peters TJ. Importance of anemia and transferrin levels in the regulation of intestinal iron absorption in hypotransferrinemic mice. Blood. 1999;94:3185–3192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor P, Martinez-Torres C, Leets I, Ramirez J, Garcia-Casal MN, Layrisse M. Relationships among iron absorption, percent saturation of plasma transferrin and serum ferritin concentration in humans. J Nutri. 1988;118:1110–1115. doi: 10.1093/jn/118.9.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bothwell TH, Charlton RW, Motulsky AG, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 7. McGraw-Hill, Inc; San Francisco: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernstein SE. Hereditary hypotransferrinemia with hemosiderosis, a murine disorder resembling human atransferrinemia. J Lab Clin Med. 1987;110:690–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beaumont C, Leneuve P, Devaux I, Scoazec JY, Berthier M, Loiseau MN, Grandchamp B, Bonneau D. Mutation in the iron responsive element of the L ferritin mRNA in a family with dominant hyperferritinaemia and cataract. Nat Gen. 1995;11:444–446. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girelli D, Corrocher R, Bisceglia L, Olivieri O, De FL, Zelante L, Gasparini P. Molecular basis for the recently described hereditary hyperferritinemia-cataract syndrome: a mutation in the iron-responsive element of ferritin L-subunit gene (the “Verona mutation”) Blood. 1995;86:4050–4053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.R’Zik S, Loo M, Beguin Y. Reticulocyte transferrin receptor (TfR) expression and contribution to soluble TfR levels. Haematologica. 2001;86:244–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kattamis A, Papassotiriou I, Palaiologou D, Apostolakou F, Galani A, Ladis V, Sakellaropoulos N, Papanikolaou G. The effects of erythropoetic activity and iron burden on hepcidin expression in patients with thalassemia major. Haematologica. 2006;91:809–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Papanikolaou G, Tzilianos M, Christakis JI, Bogdanos D, Tsimirika K, MacFarlane J, Goldberg YP, Sakellaropoulos N, Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin in iron overload disorders. Blood. 2005;105:4103–4105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tanno T, Bhanu NV, Oneal PA, Goh SH, Staker P, Lee YT, Moroney JW, Reed CH, Luban NL, Wang RH, Eling TE, Childs R, Ganz T, Leitman SF, Fucharoen S, Miller JL. High levels of GDF15 in thalassemia suppress expression of the iron regulatory protein hepcidin. Nat Med. 2007;13:1096–1101. doi: 10.1038/nm1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tanno T, Noel P, Miller JL. Growth differentiation factor 15 in erythroid health and disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:184–190. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328337b52f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tanno T, Porayette A, Orapan S, Noh S-J, Byrnes C, Bhupatiraju A, Lee YT, Goodnough JB, Harandi O, Ganz T, Paulson RF, Miller JL. Identification of TWSG1 as a second novel erythroid regulator of hepcidin expression in murine and human cells. Blood. 2009;114:181–186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hara-Kuge S, Ohkura T, Ideo H, Shimada O, Atsumi S, Yamashita K. Involvement of VIP36 in intracellular transport and secretion of glycoproteins in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16332–16339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harris ZL, Durley AP, Man TK, Gitlin JD. Targeted gene disruption reveals an essential role for ceruloplasmin in cellular iron efflux. Prod Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10812–10817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris ZL, Takahashi Y, Miyajima H, Serizawa M, MacGillivray RT, Gitlin JD. Aceruloplasminemia: molecular characterization of this disorder of iron metabolism. Prod Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2539–2543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sarkar J, Seshadri V, Tripoulas NA, Ketterer ME, Fox PL. Role of ceruloplasmin in macrophage iron efflux during hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44018–44024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kawabata H, Germain RS, Vuong PT, Nakamaki T, Said JW, Koeffler HP. Transferrin receptor 2-alpha supports cell growth both in iron-chelated cultured cells and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16618–16625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908846199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith A, Hunt RC. Hemopexin joins transferrin as representative members of a distinct class of receptor-mediated endocytic transport systems. Eur J Cell Biol. 1990;53:234–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kushner JP, Porter JP, Olivieri NF. Secondary iron overload, Hematology. Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2001:47–61. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2001.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Powell LW, Campbell CB, Wilson E. Intestinal mucosal uptake of iron and iron retention in idiopathic haemochromatosis as evidence for a mucosal abnormality. Gut. 1970;11:727–731. doi: 10.1136/gut.11.9.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cox T. Haemochromatosis: strike while the iron is hot. Nat Gen. 1996;13:386–388. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Adams PC, Reboussin DM, Barton JC, McLaren CE, Eckfeldt JH, McLaren GD, Dawkins FW, Acton RT, Harris EL, Gordeuk VR, Leiendecker-Foster C, Speechley M, Snively BM, Holup JL, Thomson E, Sholinsky P. Hemochromatosis and iron-overload screening in a racially diverse population. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1769–1778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fleming RE, Holden CC, Tomatsu S, Waheed A, Brunt EM, Britton RS, Bacon BR, Roopenian DC, Sly WS. Mouse strain differences determine severity of iron accumulation in Hfe knockout model of hereditary hemochromatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2707–2711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051630898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Girelli D, Bozzini C, Roetto A, Alberti F, Daraio F, Colombari R, Olivieri O, Corrocher R, Camaschella C. Clinical and pathologic findings in hemochromatosis type 3 due to a novel mutation in transferrin receptor 2 gene. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1295–1302. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roetto A, Papanikolaou G, Politou M, Alberti F, Girelli D, Christakis J, Loukopoulos D, Camaschella C. Mutant antimicrobial peptide hepcidin is associated with severe juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat Genet. 2003;33:21–22. doi: 10.1038/ng1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roetto A, Totaro A, Cazzola M, Cicilano M, Bosio S, D’Ascola G, Carella M, Zelante L, Kelly AL, Cox TM, Gasparini P, Camaschella C. Juvenile hemochromatosis locus maps to chromosome 1q. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1388–1393. doi: 10.1086/302379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Domenico I, Ward DM, Musci G, Kaplan J. Iron overload due to mutations in ferroportin. Haematologica. 2006;91:92–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Johnson EE, Wessling-Resnick M. Flatiron mice and ferroportin disease. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zohn IE, De Domenico I, Pollock A, Ward DM, Goodman JF, Liang X, Sanchez AJ, Niswander L, Kaplan J. The flatiron mutation in mouse ferroportin acts as a dominant negative to cause ferroportin disease. Blood. 2007;109:4174–4180. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aisen P, Enns C, Wessling-Resnick M. Chemistry and biology of eukaryotic iron metabolism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:940–959. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bali PK, Aisen P. Receptor-modulated iron release from transferrin: differential effects on N- and C-terminal sites. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9947–9952. doi: 10.1021/bi00105a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sipe DM, Murphy RF. Binding to cellular receptor results in increased iron release from transferrin at mildly acidic pH. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8002–8007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Camaschella C, Roetto A, Cali A, De Gobbi M, Garozzo G, Carella M, Majorano N, Totaro A, Gasparini P. The gene TFR2 is mutated in a new type of haemochromatosis mapping to 7q22. Nature Genet. 2000;25:14–15. doi: 10.1038/75534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Herbison CE, Thorstensen K, Chua AC, Graham RM, Leedman P, Olynyk JK, Trinder D. The role of transferrin receptor 1 and 2 in transferrin-bound iron uptake in human hepatoma cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1567–1575. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00649.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wallace DF, Summerville L, Lusby PE, Subramaniam VN. First phenotypic description of transferrin receptor 2 knockout mouse, and the role of hepcidin. Gut. 2005;54:980–986. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.062018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fleming RE, Ahmann JR, Migas MC, Waheed A, Koeffler HP, Kawabata H, Britton RS, Bacon BR, Sly WS. Targeted mutagenesis of the murine transferrin receptor-2 gene produces hemochromatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10653–10658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162360699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Merle U, Theilig F, Fein E, Gehrke S, Kallinowski B, Riedel HD, Bachmann S, Stremmel W, Kulaksiz H. Localization of the iron-regulatory proteins hemojuvelin and transferrin receptor 2 to the basolateral membrane domain of hepatocytes. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;127:221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang AS, Xiong S, Tsukamoto H, Enns CA. Localization of iron metabolism-related mRNAs in rat liver indicate that HFE is expressed predominantly in hepatocytes. Blood. 2004;103:1509–1514. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson MB, Enns CA. Diferric transferrin regulates transferrin receptor 2 protein stability. Blood. 2004;104:4287–4293. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fleming RE, Migas MC, Holden CC, Waheed A, Britton RS, Tomatsu S, Bacon BR, Sly WS. Transferrin receptor 2: continued expression in mouse liver in the face of iron overload and in hereditary hemochromatosis. Prod Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2214–2219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040548097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kawabata H, Yang R, Hirama T, Vuong PT, Kawano S, Gombart AF, Koeffler HP. Molecular cloning of transferrin receptor 2. A new member of the transferrin receptor-like family. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20826–20832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sposi NM, Cianetti L, Tritarelli E, Pelosi E, Militi S, Barberi T, Gabbianelli M, Saulle E, Kuhn L, Peschle C, Testa U. Mechanisms of differential transferrin receptor expression in normal hematopoiesis. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6762–6774. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kawabata H, Nakamaki T, Ikonomi P, Smith RD, Germain RS, Koeffler HP. Expression of transferrin receptor 2 in normal and neoplastic hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2001;98:2714–2719. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Robb A, Wessling-Resnick M. Regulation of transferrin receptor 2 protein levels by transferrin. Blood. 2004;104:4294–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kawabata H, Germain RS, Ikezoe T, Tong X, Green EM, Gombart AF, Koeffler HP. Regulation of expression of murine transferrin receptor 2. Blood. 2001;98:1949–1954. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Levy JE, Jin O, Fujiwara Y, Kuo F, Andrews NC. Transferrin receptor is necessary for development of erythrocytes and the nervous system. Nat Gen. 1999;21:396–399. doi: 10.1038/7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kawabata H, Tong X, Kawanami T, Wano Y, Hirose Y, Sugai S, Koeffler HP. Analyses for binding of the transferrin family of proteins to the transferrin receptor 2. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:464–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.West AP, Jr, Bennett MJ, Sellers VM, Andrews NC, Enns CA, Bjorkman PJ. Comparison of the interactions of transferrin receptor and transferrin receptor 2 with transferrin and the hereditary hemochromatosis protein HFE. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38135–38138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000664200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen J, Wang J, Meyers KR, Enns CA. Transferrin-directed internalization and cycling of transferrin receptor 2. Traffic. 2009;10:1488–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bennett MJ, Lebron JA, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of the hereditary haemochromatosis protein HFE complexed with transferrin receptor. Nature. 2000;403:46–53. doi: 10.1038/47417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Giannetti AM, Bjorkman PJ. HFE and transferrin directly compete for transferrin receptor in solution and at the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25866–25875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.West AP, Jr, Giannetti AM, Herr AB, Bennett MJ, Nangiana JS, Pierce JR, Weiner LP, Snow PM, Bjorkman PJ. Mutational Analysis of the Transferrin Receptor Reveals Overlapping HFE and Transferrin Binding Sites. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:385–397. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen J, Chloupkova M, Gao J, Chapman-Arvedson TL, Enns CA. HFE modulates transferrin receptor 2 levels in hepatoma cells via interactions that differ from transferrin receptor 1-HFE interactions. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36862–36870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706720200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Goswami T, Andrews NC. Hereditary hemochromatosis protein, HFE, interaction with transferrin receptor 2 suggests a molecular mechanism for mammalian iron sensing. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28494–28498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gao J, Chen J, De Domenico I, Koeller DM, Harding CO, Fleming RE, Koeberl DD, Enns CA. Hepatocyte-targeted HFE and TFR2 control hepcidin expression in mice. Blood. 2010;115:3374–3381. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gao J, Chen J, Kramer M, Tsukamoto H, Zhang AS, Enns CA. Interaction of the hereditary hemochromatosis protein HFE with transferrin receptor 2 is required for transferrin-induced hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2009;9:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Deaglio S, Capobianco A, Cali A, Bellora F, Alberti F, Righi L, Sapino A, Camaschella C, Malavasi F. Structural, functional, and tissue distribution analysis of human transferrin receptor-2 by murine monoclonal antibodies and a polyclonal antiserum. Blood. 2002;100:3782–3789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Griffiths WJ, Cox TM. Co-localization of the mammalian hemochromatosis gene product (HFE) and a newly identified transferrin receptor (TfR2) in intestinal tissue and cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:613–624. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Biasiotto G, Belloli S, Ruggeri G, Zanella I, Gerardi G, Corrado M, Gobbi E, Albertini A, Arosio P. Identification of new mutations of the HFE, hepcidin, and transferrin receptor 2 genes by denaturing HPLC analysis of individuals with biochemical indications of iron overload. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1981–1988. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.023440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wallace DF, Summerville L, Subramaniam VN. Targeted disruption of the hepatic transferrin receptor 2 gene in mice leads to iron overload. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:301–310. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Roetto A, Di Cunto F, Pellegrino RM, Hirsch E, Azzolino O, Bondi A, Defilippi I, Carturan S, Miniscalco B, Riondato F, Cilloni D, Silengo L, Altruda F, Camaschella C, Saglio G. Comparison of 3 Tfr2-deficient murine models suggests distinct functions for Tfr2-alpha and Tfr2-beta isoforms in different tissues. Blood. 2010;115:3382–3389. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-240960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chen J, Enns CA. The Cytoplasmic domain of transferrin receptor 2 dictates its stability and response to holo-transferrin in Hep3B cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6201–6209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Johnson MB, Chen J, Murchison N, Green FA, Enns CA. Transferrin receptor 2: evidence for ligand-induced stabilization and redirection to a recycling pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:743–754. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rapisarda C, Puppi J, Hughes RD, Dhawan A, Farnaud S, Evans RW, Sharp PA. Transferrin receptor 2 is crucial for iron sensing in human hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G778–783. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00157.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Girelli D, Trombini P, Busti F, Campostrini N, Sandri M, Pelucchi S, Westerman M, Ganz T, Nemeth E, Piperno A, Camaschella C. A time course of hepcidin response to iron challenge in patients with HFE and TFR2 hemochromatosis. Haematologica. 2011;96:500–506. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.033449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schmidt PJ, Toran PT, Giannetti AM, Bjorkman PJ, Andrews NC. The transferrin receptor modulates Hfe-dependent regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab. 2008;7:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Piperno A, Girelli D, Nemeth E, Trombini P, Bozzini C, Poggiali E, Phung Y, Ganz T, Camaschella C. Blunted hepcidin response to oral iron challenge in HFE-related hemochromatosis. Blood. 2007;110:4096–4100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gehrke S, Pietrangelo A, Kascak M, Braner A, Eisold M, Kulaksiz H, Herrmann T, Hebling U, Bents K, Gugler R, Stremmel W. HJV gene mutations in European patients with juvenile hemochromatosis. Clin Genet. 2005;67:425–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wallace DF, Summerville L, Crampton EM, Frazer DM, Anderson GJ, Subramaniam VN. Combined deletion of Hfe and transferrin receptor 2 in mice leads to marked dysregulation of hepcidin and iron overload. Hepatology. 2009;50:1992–2000. doi: 10.1002/hep.23198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pietrangelo A, Caleffi A, Henrion J, Ferrara F, Corradini E, Kulaksiz H, Stremmel W, Andreone P, Garuti C. Juvenile hemochromatosis associated with pathogenic mutations of adult hemochromatosis genes. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:470–479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Xia Y, Sidis Y, Andrews NC, Lin HY. Modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in vivo regulates systemic iron balance. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1933–1939. doi: 10.1172/JCI31342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Meynard D, Kautz L, Darnaud V, Canonne-Hergaux F, Coppin H, Roth MP. Lack of the bone morphogenetic protein BMP6 induces massive iron overload. Nature Genet. 2009;41:478–481. doi: 10.1038/ng.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Andriopoulos B, Jr, Corradini E, Xia Y, Faasse SA, Chen S, Grgurevic L, Knutson MD, Pietrangelo A, Vukicevic S, Lin HY, Babitt JL. BMP6 is a key endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Nature Genet. 2009;41:482–487. doi: 10.1038/ng.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kautz L, Meynard D, Besson-Fournier C, Darnaud V, Al Saati T, Coppin H, Roth MP. BMP/Smad signaling is not enhanced in Hfe-deficient mice despite increased Bmp6 expression. Blood. 2009;114:2515–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Corradini E, Garuti C, Montosi G, Ventura P, Andriopoulos B, Jr, Lin HY, Pietrangelo A, Babitt JL. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling is impaired in an HFE knockout mouse model of hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1489–1497. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ramey G, Deschemin JC, Vaulont S. Cross-talk between the mitogen activated protein kinase and bone morphogenetic protein/hemojuvelin pathways is required for the induction of hepcidin by holotransferrin in primary mouse hepatocytes. Haematologica. 2009;94:765–772. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.003541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kollia P, Samara M, Stamatopoulos K, Belessi C, Stavroyianni N, Tsompanakou A, Athanasiadou A, Vamvakopoulos N, Laoutaris N, Anagnostopoulos A, Fassas A. Molecular evidence for transferrin receptor 2 expression in all FAB subtypes of acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2003;27:1101–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Forejtnikova H, Vieillevoye M, Zermati Y, Lambert M, Pellegrino RM, Guihard S, Gaudry M, Camaschella C, Lacombe C, Roetto A, Mayeux P, Verdier F. Transferrin receptor 2 is a component of the erythropoietin receptor complex and is required for efficient erythropoiesis. Blood. 2010;116:5357–5367. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ganesh SK, Zakai NA, van Rooij FJ, Soranzo N, Smith AV, Nalls MA, Chen MH, Kottgen A, Glazer NL, Dehghan A, Kuhnel B, Aspelund T, Yang Q, Tanaka T, Jaffe A, Bis JC, Verwoert GC, Teumer A, Fox CS, Guralnik JM, Ehret GB, Rice K, Felix JF, Rendon A, Eiriksdottir G, Levy D, Patel KV, Boerwinkle E, Rotter JI, Hofman A, Sambrook JG, Hernandez DG, Zheng G, Bandinelli S, Singleton AB, Coresh J, Lumley T, Uitterlinden AG, Vangils JM, Launer LJ, Cupples LA, Oostra BA, Zwaginga JJ, Ouwehand WH, Thein SL, Meisinger C, Deloukas P, Nauck M, Spector TD, Gieger C, Gudnason V, van Duijn CM, Psaty BM, Ferrucci L, Chakravarti A, Greinacher A, O’Donnell CJ, Witteman JC, Furth S, Cushman M, Harris TB, Lin JP. Multiple loci influence erythrocyte phenotypes in the CHARGE Consortium. Nature Genet. 2009;41:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ng.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wu H, Liu X, Jaenisch R, Lodish HF. Generation of committed erythroid BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors does not require erythropoietin or the erythropoietin receptor. Cell. 1995;83:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ingley E, Tilbrook PA, Klinken SP. New insights into the regulation of erythroid cells. IUBMB life. 2004;56:177–184. doi: 10.1080/15216540410001703956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sathyanarayana P, Dev A, Fang J, Houde E, Bogacheva O, Bogachev O, Menon M, Browne S, Pradeep A, Emerson C, Wojchowski DM. EPO receptor circuits for primary erythroblast survival. Blood. 2008;111:5390–5399. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]