SYNOPSIS

Objectives

We estimated self-reported secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure in California at home and at work.

Methods

We used data from the 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys (n=109,809) for home exposure analysis, and we used data from the 2002 and 2005 California Tobacco Surveys (n=12,883) for workplace exposure analysis. Differences in exposure by age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic characteristics were assessed using Chi-square tests and multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Results

In the home, children had the lowest rates of SHS exposure (3.4%), followed by adolescents (4.7%) and adults (6.0%). For all age groups, Hispanic people had the lowest exposure to SHS at home, and black people of all ages had higher exposure rates than white people. In the workplace, 12.9% of Californians were exposed to SHS. Men had higher rates of exposure than women, and rates declined with age. Hispanic people had the highest rates of SHS exposure at work (19.5%), followed by Asian/Pacific Islanders (10.5%), black people (10.4%), and white people (9.7%). Workplace exposure rates were highest for people who worked in stores or warehouses, followed by plants or factories, restaurants or bars, and vehicles.

Conclusions

Despite many years of tough tobacco-control policies in California, people continue to be exposed to SHS at home and in the workplace. The policies that are already in place, such as smoke-free workplace laws, need to be fully enforced. Interventions for reducing SHS exposure should be targeted to the groups with the greatest exposure rates, including Hispanic people, black people, young adults, and those who work in high-exposure settings.

Exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) has been documented to result in a number of adverse health effects, including respiratory illness, cancer, and heart disease in adults and respiratory effects in children.1,2 Studies that examine differences in exposure by racial/ethnic group indicate that black people have the highest rates of exposure while Hispanic people report lower levels of exposure.3–5 Differences have also been reported by age, gender, and place of exposure.2

Nationally, 88 million nonsmokers were exposed to SHS in 2007–2008, including nearly all nonsmokers who lived with someone who smoked inside the home.6 California has made great strides in reducing exposure to SHS in recent years, with 85% of black households, 88% of Asian households, and 92% of Hispanic households reporting that they were smoke-free as early as 1999.7 During this same time period, national data indicate that only 60.2% of homes had smoke-free rules.8 Similar protections have been adopted in the California workplace, with the implementation of California Assembly Bill 13 (AB-13) in 1995, which prohibited smoking of tobacco products in most enclosed workplaces.9 These provisions were extended to bars, taverns, and clubs in 1998, though some exceptions are allowed, including some hotel rooms, designated smoking areas in hotel lobbies, tobacco shops, truck cabs, warehouse facilities, and ventilator-enclosed employee break rooms.10 As one of the first states to adopt workplace smoking restrictions, California was considered to be a leader in protecting workers from SHS exposure. However, the law has not been modified since its passage, and the exemptions have resulted in many Californians continuing to be exposed to SHS at work.

The purpose of this study was to (1) estimate the proportion of nonsmoking black people, Hispanic people, Asian/Pacific Islanders (A/PIs), American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs), and other Californians who are exposed to SHS at home and in the workplace; and (2) analyze the socioeconomic correlates of SHS exposure.

METHODS

Data sources

The 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys (CHISs) were used to analyze SHS exposure at home.11 The CHIS is a population-based telephone survey of California households that has been conducted every two years since 2001. It uses a multistage, stratified, random-digit-dial sampling frame, and oversamples racial/ethnic minority groups. Among households screened and determined to be eligible, the adult sample survey response rate was 54.0% and 52.8% in the 2005 and 2007 surveys, respectively. The survey contains information about adult and adolescent smoking and how many days per week there is smoking inside the home. Data from 2005 and 2007 were pooled to increase the sample size to allow estimation by race/ethnicity. The combined 2005 and 2007 CHISs contained data on 109,809 nonsmokers including 4,446 black people; 25,426 Hispanic people; 9,873 A/PIs; and 672 AI/ANs.

The 2002 and 2005 California Tobacco Surveys (CTSs) were used to study SHS exposure in the workplace.12,13 The CTS is a computer-assisted telephone survey that solicits detailed information on cigarette smoking behavior, attitudes toward smoking, media exposure to smoking, and use of tobacco products other than cigarettes. Data from the 2002 and 2005 CTS adult files were pooled to increase the sample size to allow us to develop estimates by race/ethnicity. All young adults aged 18–29 years were selected for interview, with response rates of 58.3% and 48.9% in 2002 and 2005, respectively. Adults aged ≥ 30 years were selected based on their race/ethnicity and smoking status. Among retained older adults, the response rates were 67.2% and 56.3% in the two survey years.

The final sample of nonsmoking adults who worked in indoor settings outside of their homes contained 12,883 adults, including 1,257 black people, 3,281 Hispanic people, and 1,559 A/PIs. The data did not permit us to estimate workplace exposure for AI/ANs due to inadequate sample size. The CTS could not be used for a detailed analysis of home exposure because the questions focus on smoking restrictions in the household rather than SHS exposure.12,13

Study sample

Though smokers and nonsmokers alike suffer the consequences of SHS exposure, it is difficult to separate the impact of active and passive smoking for a smoker. Therefore, we focused our analyses on nonsmokers in this study. For the analyses of SHS exposure at home, we examined three age groups separately: children aged 0–11 years, nonsmoking adolescents aged 12–17 years, and nonsmoking adults ≥18 years of age. Our analysis of SHS exposure in the workplace was limited to nonsmoking adults who worked in indoor settings outside their homes. All children were assumed to be nonsmokers. Nonsmoking adolescents were defined as those who had never tried cigarette smoking or who did not smoke in the past 30 days. Nonsmoking adults were defined as those who had never smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime or who did not currently smoke.

Measurement of SHS exposure

Homes with SHS exposure were identified in the CHIS adult files as those households in which (1) smoking was ever allowed inside the home and (2) someone smoked inside the home at least one day per week. Adults exposed to SHS at home were defined as nonsmokers who lived in a home with SHS exposure. We linked the household identifiers to the adolescent files and children files to identify adolescents and children who were exposed to SHS at home. Those exposed to SHS in the workplace were defined using the CTS adult files as nonsmokers who worked in indoor settings outside of their home and who reported that someone smoked in their work area in the past two weeks.

Covariates

Covariates considered in the multivariate regression models included sociodemographic characteristics, living in a rural or urban area, household size, whether the workplace was smoke-free, and type of workplace. Sociodemographic characteristics included gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic AI/AN, non-Hispanic A/PI, and non-Hispanic other), education (<high school, high school graduate or general equivalency diploma, some college, and ≥college), and poverty status. Poverty status was measured using the poverty income ratio developed by the U.S. Census Bureau,14 which is the ratio of family income to the family's poverty threshold given family size. We classified the poverty income ratio into four categories: poor (0.00—0.99), low income (1.00–1.99), middle income (2.00–3.99), and high income (≥4.00). Values <1.00 indicate that family income is below the official poverty threshold. Education status for children and adolescents was determined by the educational status of the head of household. Smoke-free workplaces were determined by the response to the question, “Is your place of work completely smoke-free indoors?”

Statistical analysis

We conducted analyses using SAS® version 9.2.15 All analyses accounted for the complex survey design and incorporated sampling weights that adjusted for unequal probabilities of sample selection, non-response, and sample noncoverage to derive unbiased estimates for the California population. We estimated the percentage of nonsmokers with self-reported SHS exposure at home and in the workplace. Exposure rates were also estimated by age group, sociodemographic characteristics, and other covariates. We compared differences in SHS exposure rates between population subgroups using the Chi-square test.16 Estimates were considered statistically significant if the p-value from a two-tailed test was <0.05. We conducted a separate analysis to examine the characteristics of those adults who worked in smoke-free workplaces but nonetheless reported being exposed to SHS at work.

Multivariate logistic regression models, which controlled for the covariates, were estimated to examine the likelihood of being exposed to SHS at home or in the workplace. From the estimated models, we calculated adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each covariate.

RESULTS

Home exposure

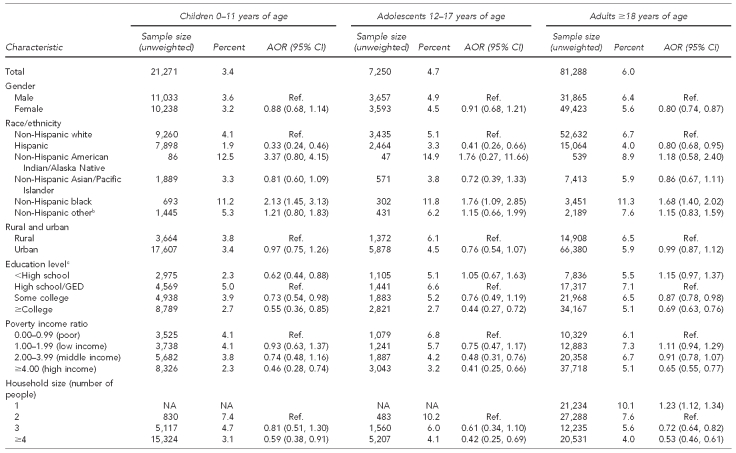

Rates of exposure to SHS at home were lowest for children (3.4%), followed by adolescents (4.7%) and adults (6.0%) (Table 1). After controlling for other covariates, Hispanic children had lower exposure rates (AOR=0.33) and black children had higher rates (AOR=2.13) as compared with white children. The highest rates were for AI/ANs, but the sample sizes were too small to show statistical significance. Children living in households headed by an individual with some college education had lower rates of exposure than those in households headed by an individual with a high school education, and those in high-income households had the lowest rates of SHS exposure compared with children in poor households. Children living in households of four or more people had lower SHS exposure rates than those in two-person households (3.1 vs. 7.4, respectively).

Table 1.

Percentage of nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke at home, by age and sociodemographic characteristics: California, 2005–2007a

aData source: 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Surveys. University of California Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research. California Health Interview Survey: survey design & methods [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.chis.ucla.edu/methodology.html

bIncludes any single race not listed in table or any two or more races

cFor children and adolescents, these categories reflect the educational attainment of the head of household.

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

Ref. = reference group

GED = general equivalency diploma

NA = not applicable

Among adolescents, Hispanic people had lower exposure rates (AOR=0.41) and black people had higher exposure rates (AOR=1.76) compared with white people. Again, the highest rate was for AI/AN adolescents, but this rate was not statistically significant. Exposure rates were significantly lower for adolescents living in households headed by someone with a college education, with high or middle income, and with a household size of four or more people.

After controlling for other factors, adult women had significantly lower home SHS exposure than men (AOR=0.80). Compared with white adults, black adults had a higher exposure rate (AOR=1.68), while Hispanic adults had a lower exposure rate (AOR=0.80). Adults with at least some college education or a college degree, in high-income households, and living in larger households had lower home SHS exposure rates than those who lived alone.

Workplace exposure

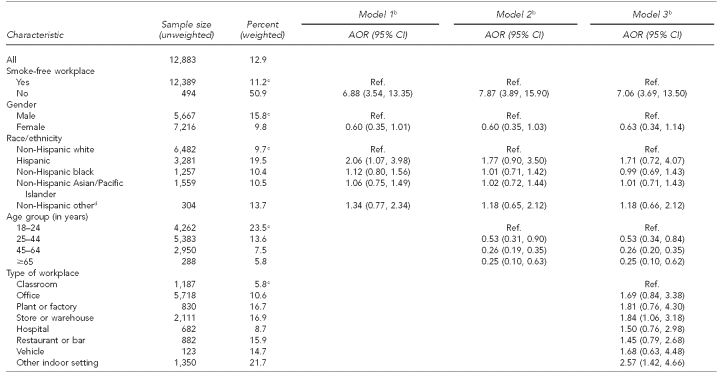

Table 2 shows that all of the variables in the models—smoke-free workplace, gender, race/ethnicity, age group, and type of workplace—were significant determinants of SHS exposure. Men had higher rates of workplace exposure than women (15.8% vs. 9.8%), and rates declined with age, from 23.5% for those aged 18–24 years to 5.8% for those aged ≥65 years. Hispanic people had the highest rates of workplace exposure (19.5%), followed by non-Hispanic other (13.7%), A/PIs (10.5%), black people (10.4%), and white people (9.7%). The highest workplace exposure rates reported for specific settings were for people who worked in stores or warehouses, followed by plants or factories, restaurants or bars, and vehicles. In 2002–2005, 12.9% of Californians continued to be exposed to SHS in the workplace, including 11.2% of those who worked in smoke-free workplaces and 50.9% of those who did not work in smoke-free workplaces.

Table 2.

Percentage of nonsmoking adults who worked in indoor settings outside the home and were exposed to secondhand smoke at work in the last two weeks, by sociodemographic and other characteristics: California, 2002–2005a

aData source: 2002 and 2005 California Tobacco Surveys

bModel 1 includes smoke-free workplace, gender, and race/ethnicity. Model 2 includes the variables in Model 1 plus age group. Model 3 includes the variables in Model 2 plus type of workplace.

cp<0.05 from Chi-square test

dIncludes American Indian/Alaska Native and any other category not listed in table

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

Ref. = reference group

We ran three multivariate logistic regression models of the likelihood of being exposed to SHS in the workplace (Table 2). We did not include education or income in these models because they were both highly correlated with whether or not the workplace was smoke-free, the type of workplace, and age. The results from Model 1 indicated that those working in a place that was not smoke-free were nearly seven times more likely to be exposed to SHS than those in non-smoke-free workplaces. Hispanic people were twice as likely to be exposed as white people. When age was added to the model (Model 2), the Hispanic effect was no longer significant, perhaps reflective of the relatively young age of the California Hispanic population. People older than 25 years of age were less likely to be exposed to SHS at work than 18- to 24-year-olds. Model 3 indicated that even after controlling for age and the impact of smoke-free workplace laws, people working in stores or warehouses were nearly twice as likely, and people working in other indoor settings were about 2.6 times as likely to be exposed to SHS as those working in classrooms.

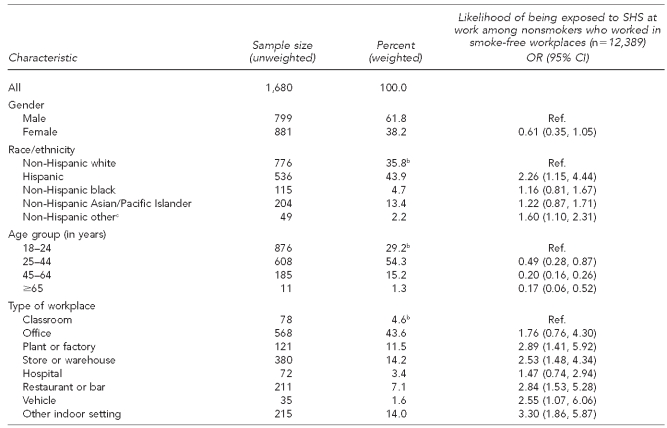

Table 3 shows that the people most likely to be exposed to SHS in smoke-free workplaces were young (<45 years of age), male, and Hispanic. Among these people, those who worked in a plant or factory, store or warehouse, restaurant or bar, or vehicle were nearly three times as likely to be exposed in a smoke-free workplace as those who worked in a classroom.

Table 3.

Characteristics of nonsmoking adults who worked in indoor settings outside the home and were exposed to SHS in a smoke-free workplace: California, 2002–2005a

aData source: 2002 and 2005 California Tobacco Surveys

bp<0.05

cIncludes American Indian/Alaska Native and any other category not listed in the table

SHS = secondhand smoke

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

Ref. = reference group

DISCUSSION

In California, a state with a highly successful tobacco-control program, many people are still being exposed to SHS at home and in the workplace. Our findings translate into more than 400,000 children, 300,000 adolescents, and 2.7 million nonsmoking adults being exposed to SHS at home and 2.7 million nonsmoking adults being exposed in the workplace. Our finding that California children were the least likely to be exposed to SHS at home among the age groups is the opposite of what national data show.6,17 This relationship merits further exploration, preferably using a single data source that permits comparison of California and other state SHS exposure rates. Also, nationally, home is the most likely place of SHS exposure, but nonsmokers in California are more likely to be exposed at work.17

Importantly, some Californians are more likely to be exposed to SHS than others. At home, black people were most likely to be exposed to SHS, while at work Hispanic people were most likely to be exposed to SHS among all three age groups. Our findings suggest that AI/ANs may have the highest home exposure rates of any racial/ethnic group, but the sample size was too small to show statistical significance. We were unable to analyze their workplace exposure, again due to inade-quate data. Further research should be conducted to examine the exposure rates in this population using a dataset that is better suited for this purpose.

In California in 2005, 94.8% of nonsmoking adults who worked in indoor settings indicated that their workplace was smoke-free.18 Despite this statistic, we found that nearly 13% of nonsmoking adults working in indoor settings reported being exposed to SHS at work. Those exposed were most likely to be Hispanic; young; and working in plants or factories, stores or warehouses, restaurants or bars, or vehicles. This finding suggests at least three factors that may be at play. First, it is possible that Hispanic people and young adults are more likely to work in the few settings that are not covered under smoke-free legislation. Second, it might reflect confusion about the meaning of a smoke-free workplace law. In California, Labor Code Section 6404.5 includes a number of exemptions.19 Thus, people who report that their workplace is smoke-free but that smoking occurs may not be aware that smoking is allowed in certain areas under the current law. Third, it suggests that enforcement of existing smoke-free laws may be lax.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, we used different datasets to analyze home and workplace SHS exposure because there is not a single dataset that contains home and workplace exposure measures for California. Second, we included only exposure reported as occurring at home and in indoor -workplaces, although people may also be exposed to SHS in other venues, such as parks, casinos, public buildings, and outdoor workplace settings. Third, it is possible that people may have misrepresented their exposure (e.g., reporting smoke-free homes when their homes were not smoke-free). We are unaware of any studies that have examined the extent of such misrepresentation, because the biomarkers that could be used to validate exposure do not differentiate place of exposure. Fourth, our analyses were limited to nonsmokers, although smokers suffer negative health impacts from SHS in addition to the effects of active smoking. Fifth, recent research suggests that SHS exposure among children is greater for those who live in multiunit housing,20 but we were unable to address this issue using the datasets for our study. Finally, both the CHIS and the CTS are conducted by telephone. The impact of the increasing use of cellular telephones instead of landline telephones creates sampling challenges for all telephone-based surveys, and may lead to particular biases for younger adults.

Strengths

This study also had a number of strengths. Our measures of SHS exposure have advantages over some of the measures that have been used in other studies. The CHIS defines SHS exposure in the home by including households that not only permit smoking, but also those in which smoking actually occurs at least one day a week. A number of studies have defined SHS exposure as occurring if a nonsmoker lives with a smoker, without determining if that person actually smokes in the home. The CTS defines SHS exposure as occurring if a nonsmoker reports that someone smoked in their work area in the past two weeks. A number of studies have defined SHS exposure based on whether someone lived with a smoker or whether smoking was permitted, rather than if it actually occurred. Other studies take the measurement one step further, by using a biomarker such as serum or urinary cotinine to measure actual exposure. This measure has the advantage of capturing the combined exposure from all settings, but the disadvantage of not knowing where the exposure took place. Additional strengths of this study included a detailed analysis of the risk of SHS exposure among the different racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups in California, and use of the most recent home and workplace exposure data available for California.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite many years of tough tobacco-control policies in California, people continue to be exposed to SHS at home and in the workplace. The policies that are already in place, such as smoke-free workplace laws, need to be fully enforced. Loopholes in the current labor code relating to workplace tobacco exposure need to be eliminated so that California can truly have a comprehensive smoke-free workplace policy. Programs need to be developed to help protect those at greatest risk in the state (i.e., Hispanic people, black people, young workers, and those who work in high-exposure settings). Additional work needs to be done to eliminate disparities in SHS exposure and to protect all state residents from the harmful effects of tobacco exposure.

Footnotes

This research was funded by the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (grant #16RT-0075). Additional funding was obtained from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI). The research was conducted as part of the UCSF FAMRI Bland Lane Center of Excellence on Second Hand Smoke. The authors thank colleagues at the UCSF FAMRI and the UCSF Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education for their encouragement and for many helpful suggestions. This study was approved as exempt by the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.California Environmental Protection Agency. Sacramento (CA): California Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment; 2005. Proposed identification of environmental tobacco smoke as a toxic air contaminant. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Washington: HHS, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Smoking and Health (US); 2006. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarinci IC, Watson JM, Slawson DL, Klesges RC, Murray DM, Eck-Clemens LH. Socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and environmental tobacco exposure among non-smoking females. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2:355–61. doi: 10.1080/713688150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sexton K, Adgate JL, Church TR, Hecht SS, Ramachandran G, Greaves IA, et al. Children's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: using diverse exposure metrics to document ethnic/racial differences. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:392–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagenknecht LE, Manolio TA, Sidney S, Burke GL, Haley NJ. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure as determined by cotinine in black and white young adults: the CARDIA study. Environ Res. 1993;63:39–46. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1993.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vital signs: nonsmokers' exposure to secondhand smoke—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilpin EA, Emery SL, Farkas AJ, Distefan JM, White MM, Pierce JP. La Jolla (CA): University of California, San Diego; 2001. The California Tobacco Control Program: a decade of progress, results from the California Tobacco Surveys, 1990–1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.State-specific prevalence of smoke-free home rules—United States, 1992–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(20):501–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.California Department of Industrial Relations. San Francisco: Cal/OSHA Consultation Service; 1997. [cited 2010 Sep 15]. AB-13 fact sheet—California workplace smoking restrictions. Also available from: URL: http://www.dir.ca.gov/dosh/dosh_publications/smoking.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.California Air Resources Board. Report to the California Legislature: indoor air pollution in California. San Francisco: California Environmental Protection Agency; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.University of California Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research. California Health Interview Survey: survey design & methods. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.chis.ucla.edu/methodology.html.

- 12.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Berry CC, White MM. La Jolla (CA): University of California, San Diego; 2003. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Technical report on analytic methods and approaches used in the 2002 California Tobacco Survey analysis. Volume 1: data collection methodology. Also available from: URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/ssds/pub/CTS/cpc00007/2002finaltech-rpt-vol1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Delaimy WK, Messer K, Pierce JP, Trinidad DR, White MM. La Jolla (CA): University of California, San Diego; 2007. [cited 2011 Aug 8]. Technical report on analytic methods and approaches used in the 2005 California Tobacco Survey analysis. Volume 1: data collection methodology. Also available from: URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/ssds/pub/CTS/cpc00008/2005%20Final%20TECH%20Report-Vol.%201.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Census Bureau (US) How the Census Bureau measures poverty. [cited 2011 Aug 2]; Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/about/overview/measure.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15.SAS Institute Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2009. SAS®: Version 9.2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Max W, Sung HY, Shi Y. Who is exposed to secondhand smoke? Self-reported and serum cotinine measured exposure in the U.S., 1999–2006. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:1633–48. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6051633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Delaimy WK, White MM, Trinidad DR, Messer K, Gilmer T, Zhu SH, et al. Volume 2. Sacramento (CA): California Department of Public Health; 2008. The California Tobacco Control Program: can we maintain the progress? Results from the California Tobacco Survey, 1990–2005. [Google Scholar]

- California Labor Code §6400-6413.5.

- 20.Wilson KM, Klein JD, Blumkin AK, Gottlieb M, Winickoff JP. Tobacco-smoke exposure in children who live in multiunit housing. Pediatrics. 2011;127:85–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]