Abstract

Rationale

Nitric oxide, the classic endothelial derived relaxing factor (EDRF), acts via cyclic GMP and calcium without notably affecting membrane potential. A major component of EDRF activity derives from hyperpolarization and is termed endothelial derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF). Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a prominent EDRF, since mice lacking its biosynthetic enzyme, cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), display pronounced hypertension with deficient vasorelaxant responses to acetylcholine.

Objective

The purpose of this study is to determine if H2S is a major physiologic EDHF.

Methods and Results

We now show that H2S is a major EDHF, as in blood vessels of CSE deleted mice hyperpolarization is virtually abolished. H2S acts by covalently modifying (sulfhydrating) the ATP-sensitive potassium channel, as mutating the site of sulfhydration prevents H2S-elicited hyperpolarization. The endothelial intermediate conductance (IKCa) and small conductance (SKCa) potassium channels mediate in part the effects of H2S, as selective IKCa and SKCa channel inhibitors, charybdotoxin and apamin, inhibit glibenclamide insensitive H2S induced vasorelaxation.

Conclusions

H2S is a major EDHF that causes vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cell hyperpolarization and vasorelaxation by activating the ATP-sensitive, intermediate conductance and small conductance potassium channels through cysteine S-sulfhydration. As EDHF activity is a principal determinant of vasorelaxation in numerous vascular beds, drugs influencing H2S biosynthesis offer therapeutic potential.

Keywords: Hydrogen Sulfide, EDHF, Hyperpolarization, Potassium Channel, Sulfhydration

Introduction

Multiple molecular mechanisms regulate blood vessel relaxation with nitric oxide (NO) well established as a mediator of endothelial dependent vasorelaxation (endothelial derived relaxing factor, EDRF).1–3 While NO acts by both stimulating cyclic GMP (cGMP) levels and in a cGMP-independent manner to influence calcium disposition and sensitivity,4 blood vessel relaxation and tone are also prominently mediated by endothelial dependent hyperpolarization.5–7 Numerous substances have been advanced as putative Endothelial Derived Hyperpolarizing Factors (EDHFs) including metabolites of arachidonic acid from cyclooxygenase, prostacyclin (PGI2), epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) derived from cytochrome P450, lipoxygenase (12-(s)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-S-HETE)), reactive oxygen species, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), potassium ions (K+), vasoactive peptides, as well as NO itself.5–8 It has also been suggested that EDHF function may be mediated through direct coupling between endothelial and smooth muscle cells by myoendothelial gap junctions composed of connexins.5–7

Recently, H2S has been shown to be a major EDRF, formed in vascular endothelial cells from cysteine by cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) which is calcium-calmodulin dependent.9 While CSE appears to play a significant role in the cardiovascular system, two other enzymes have also been shown to generate H2S in various tissues, namely cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST). In blood vessels however, CBS appears to play a negligible role in the production of H2S,10 whereas 3-MST's precise role has yet to have been defined despite its presence in vascular endothelium.11 Acetylcholine-mediated blood vessel relaxation however is markedly reduced in CSE deleted mice, which manifest increased blood pressure comparable to levels in mice lacking endothelial NO synthase (NOS).9, 12 Utilizing genetic deletion of CSE and other approaches, we now show that H2S is a major EDHF acting by chemically modifying sulfhydryl groups – sulfhydration – of potassium channels.

Methods

Myograph Measurements of Vascular Tension

The segments (1–1.5 mm in length) of mesenteric arteries or aortas from 8–12-week-old male animals were used for myograph measurements of vascular tension as described before.13 Briefly, the mice were heparinized 1 h before sacrifice. Once euthanized, the arteries were carefully excised and cleaned from the surrounding fat and placed in a Petri dish containing ice-cold Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate solution at pH 7.4 (concentrations in mM: 118.3 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.2* KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgSO4, and 11.1 dextrose). The vessels were then carefully placed in the multi-wire myograph system DMT 610M bubbling with continuous of oxygen gas (95% O2 and 5% CO2) at 37°C and incrementally stretched for optimized contractility. Phenylephrine was then applied to pre-constrict the vessels, following which changes in vascular tension were recorded with application of different pharmacologic agents. In some experiments, endothelium removal was performed as described before.14

Vessel Diameter Measurements

Vessels were prepared as described above, cannulated at both ends with glass micropipettes (80–100 µm), secured with nylon monofilament suture, and placed in a microvascular chamber (Living Systems, Burlington, VT). Vessels were studied in the absence of flow and maintained at a constant transmural pressure of 70 mmHg as described before.15, 16 The chamber was superfused with Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate solution, maintained at 37°C, pH 7.4, and gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The chamber was then placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon TMS-F) connected to a video camera (Panasonic CCTV camera). The vessel image was projected on a video monitor, and the internal diameter continuously determined by a video dimension analyzer (Living Systems Instrumentation) with BIOPAC data acquisition system (Santa Barbara, CA). Changes in vessel diameter were measured with application of different pharmacologic agents.

Membrane Potential Measurements

Membrane potentials were measured as described before17–19 but with modifications. Briefly, vessels were prepared as above, fixed by pinning one end and cut open in the longitudinal plane. Each corner was pulled out enough, and pinned (0.125 mm diameter tungsten pins), such that the cellular layers remained intact. The vessels were maintained at 37°C in Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate solution at pH 7.4, loaded with 100 nM DiBAC4(3) dye (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) or FLIPR red dye (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and maintained in the dark for 30 min. Majority of the experiments were conducted using the DiBAC dye unless otherwise indicated. Each tissue was then mounted under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i Microscope with Roper Scientific Camera) and the system set at an exposure time of 100 msec with a sampling rate of 3 images / sec. FITC filter (Fluorescein isothiocyanate) was used since the dye has an excitation of 488 nm and a peak emission of 518 nm. Changes in fluorescence intensities were then recorded with addition of various drugs in small volumes without disturbing the focus. A similar process was used for cultured cells, but the FlexStation-3 fluorescence microplate reader system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was used instead.

S-Sulfhydration (Modified Biotin Switch) Assay

The assay was carried-out as described previously20 but with modifications. Briefly, arteries or cells treated with appropriate stimulants such as NaHS or acetylcholine were homogenized in HEN buffer (250 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.7, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM Neocuproine) supplemented with 100 µM deferoxamine (DFO) and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Lysates (240 µg) were added to blocking buffer (HEN buffer plus 25% SDS and 20 mM methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS)) at 50°C for 20 min with frequent vortexing. The MMTS was then removed by acetone and the proteins precipitated at −20°C for 20 min. After acetone removal, the proteins were resuspended in HENS (HEN + SDS) buffer. To the suspension was added 4 mM biotin-N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3'-(2'-pyridyldithio)propionamide (HPDP) in DMSO without ascorbic acid. After incubation for 4 h at 25°C, biotinylated proteins were precipitated by streptavidin-agarose beads, which were then washed with HENS buffer. The biotinylated proteins were eluted by SDS-PAGE sample buffer and subjected to Western blot analysis.

CSE Activity Assays

CSE protein was purified and its activity assayed using the tissue homogenate method as described previously21 with the exception of a pre-incubation step with 100 nM S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO) at 37°C for 2 h.

Shear Stress Experiments

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) were grown to ~80% confluence and subjected to a laminar shear stress of 20 dynes / cm2 for 24 h using a cone-and-plate viscometer as described earlier.22, 23 The cells were then scrapped for CSE activity assay.

Additional Methods can be found as an Online Supplement available at http://circres.ahajournls.org.

Results

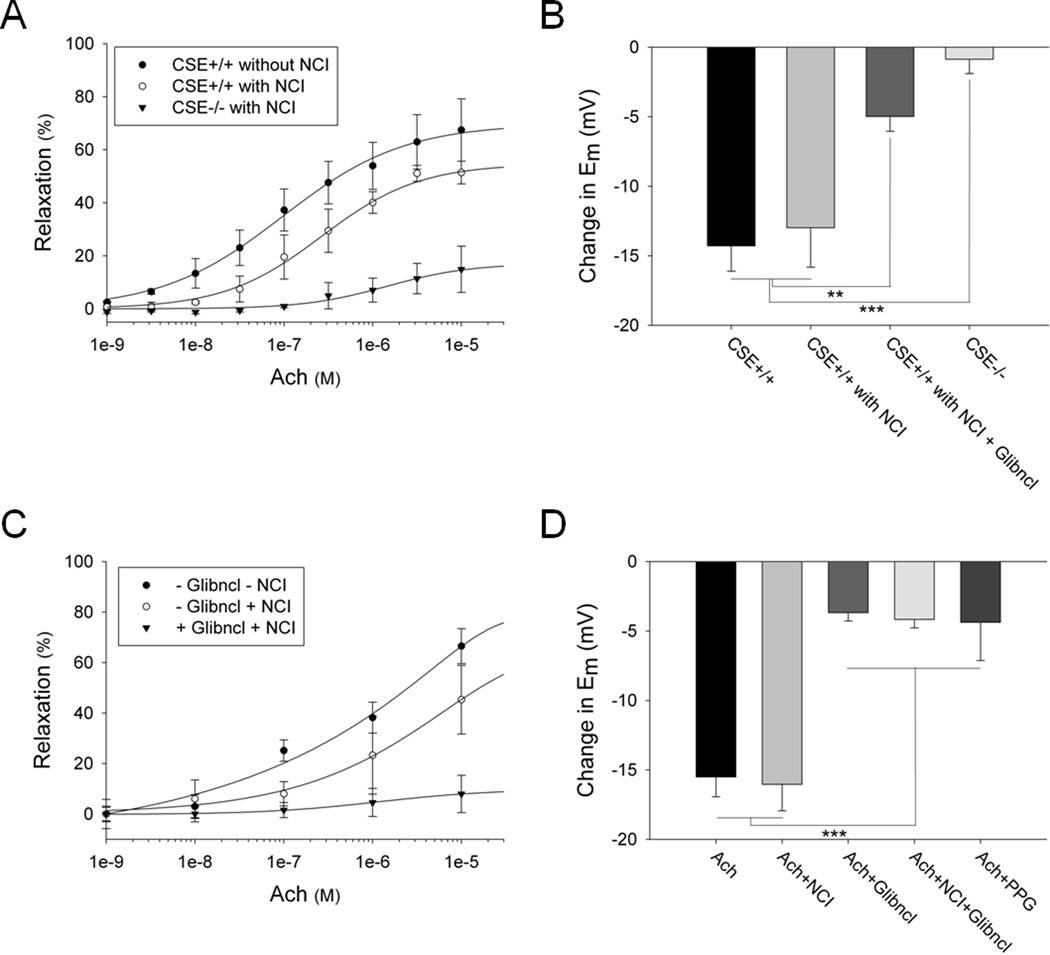

Cholinergic vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization are significantly reduced in CSE−/− and glibenclamide treated vessels

We confirm the importance of H2S in mediating muscarinic cholinergic-dependent vasorelaxation of the smaller mesenteric artery (diameter of 80–200 µm in mice) and larger aorta (diameter of 350–450 µm in mice) using force-tension myography and vessel diameter measurements (Figure 1A, Online Figure IA and IVA). We eliminated influences of NOS and cyclooxygenase (COX) products by treatment with appropriate inhibitors (L-NAME 100 µM and indomethacin 10 µM respectively). L-NAME nearly abolishes NO generation in both wild-type and CSE knockout vessels (Online Figure II), which display similar basal NO productions (Online Figure II). In the mesenteric arteries, the overall cholinergic relaxation, of which about 75 – 80% is NOS/COX independent, is reduced by ~ 60% in CSE deleted animals (Figure 1A). Conversely, in the aorta, cholinergic relaxation appears to be primarily NOS/COX dependent and is reduced by less than 25% in CSE knockout vessels treated with NOS/COX inhibitors (Online Figure IVA). To study the effects of H2S on cellular membrane potential, we used two potentiometric fluorescent probes (Online Figure III): 1) DiBAC, a probe with slow response time and 2) FLIPR, a newer dye with increased sensitivity and rapid response time. While the authors acknowledge that electrophysiologic techniques such as whole-cell patch clamping are the gold standard for investigating channel function, the use of fluorescent voltage-sensitive dyes to interrogate channels in a rapid, high throughput and economical manner is rapidly emerging. Indeed studies have shown dye responses to ligand-evoked activation of potassium channels to be comparable with whole-cell patch clamp measurements.17–19 Employing the dyes, we find that cholinergic relaxation is associated with pronounced hyperpolarization of about 13 to 16 mV in mesenteric arteries and about 6 to 8 mV in the aorta (Figure 1B and Online Figure IVB). For the NOS/COX independent system, CSE deletion virtually abolishes hyperpolarization. The importance of potassium channels for cholinergic vasorelaxation is evident in that vasorelaxation is markedly reduced in the presence of 30 mM KCl which fully blocks all potassium channels. (Online Figure IB). Several potassium channels have been implicated in vasorelaxation, with the ATP-sensitive channels closely linked to H2S and EDHF.24, 25 The channel inhibitor glibenclamide reduces hyperpolarization about ~ 65% (Figure 1B and Online Figure IVB). Thus, cholinergic vasorelaxation primarily reflects H2S hyperpolarizing cells via the ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Cholinergic vasorelaxation in mouse mesenteric artery (Figure 1C) as well as vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization in rat mesenteric artery (Figure 1D and Online Figure V) are also largely independent of NOS and COX and prevented by glibenclamide. The same is true for hyperpolarization in rat aorta, even though overall vasorelaxation is dependent on the NOS/COX system (Online Figure IVC, D). In addition, the CSE inhibitor propargylglycine (PPG) significantly reduces cholinergic hyperpolarization in mesenteric arteries (Figure 1D). Since elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) might contribute to endothelium dysfunction, we measured differences in ROS levels in the vessels of wild-type and CSE knockout mice. We did not however observe any significant difference in basal ROS production between wild-type and knockout arteries (Online Figure VI).

Figure 1. Cholinergic vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization are significantly reduced in CSE knockout and glibenclamide treated mesenteric arteries.

(A) Muscarinic cholinergic-dependent vasorelaxation of the mesenteric artery, measured using force-tension myography, is markedly diminished in CSE knockout mice compared to wild-type controls. The NOS and COX enzymes were inhibited by treatment with L-NAME (100 µM) and indomethacin (10 µM) respectively. NOS/COX inhibitors (NCI), Acetylcholine (Ach). n = 15. (B) CSE deletion almost completely abolishes the cholinergic-dependent hyperpolarization in mesenteric arteries. Treatment of wild-type mesenteric arteries with glibenclamide (5 µM) reduces the hyperpolarization by about 65%. Some of the samples were treated with L-NAME (100 µM) and indomethacin (10 µM) as indicated. The changes in membrane potential (Em) were measured with the voltage-sensitive dyes DiBAC and FLIPR. Acetylcholine was used at 10 µM. n = 24. (C) Cholinergic vasorelaxation is markedly diminished in mouse mesenteric arteries treated with glibenclamide (5 µM) in the presence of L-NAME (100 µM) and indomethacin (10 µM). n = 6. (D) Acetylcholine-mediated hyperpolarization is significantly reduced in rat mesenteric arteries treated with glibenclamide (5 µM) or propargylglycine (PPG) (10 µM). L-NAME (100 µM) and indomethacin (10 µM) do not influence membrane hyperpolarization. n = 13. All results are mean ± SEM (**p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001).

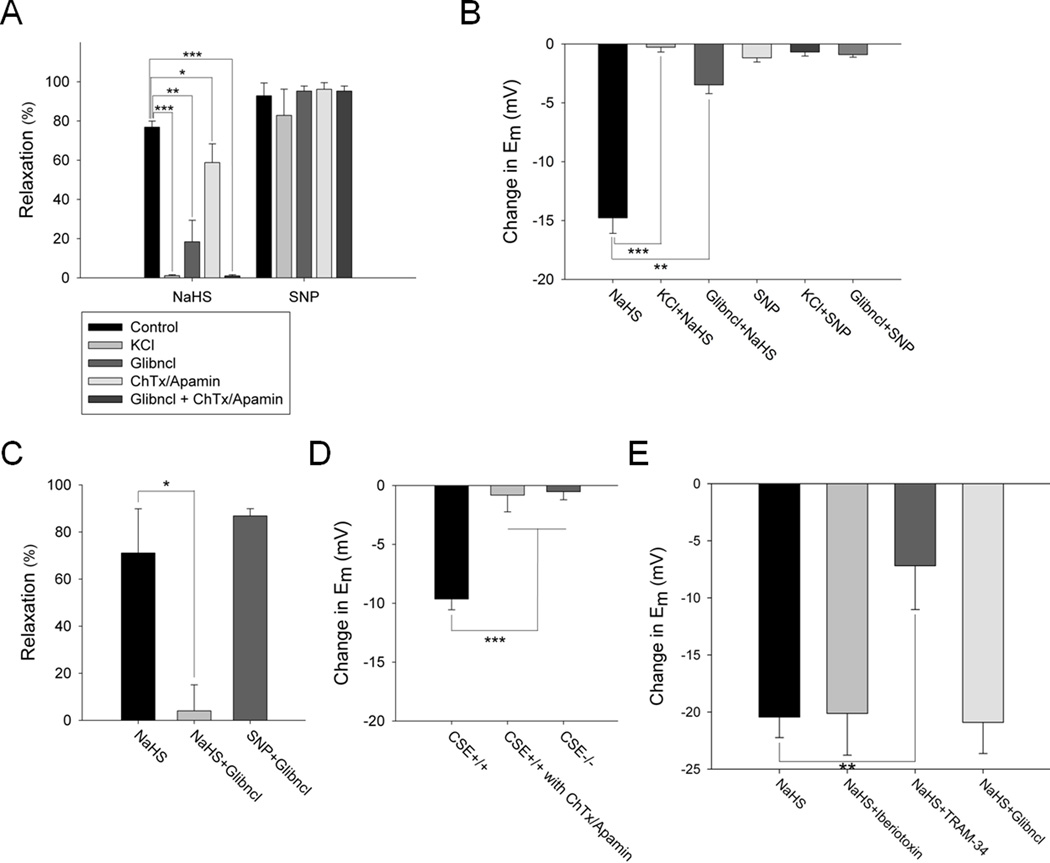

KCl and glibenclamide markedly diminish H2S vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization in intact and endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries

The vasorelaxing and hyperpolarizing actions of applied H2S involve potassium channels, since they are blocked by 30 mM KCl, which fails to alter NO responses (Figure 2A, B and Online Figure VIIIA, B). The H2S-mediated vasorelaxation is not affected by changes in the buffer oxygen concentration as relaxation is comparable in buffer bubbled with 95% oxygen and HEPES buffer containing the ambient 21% oxygen (Online Figure VII). H2S acts primarily via ATP-sensitive potassium channels, as glibenclamide (5 µM) markedly reduces the H2S precursor sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS)-elicited vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization (Figure 2A, B and Online Figure VIIIA, B). In contrast, glibenclamide fails to influence relaxation in response to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 1 µM). NO, but not H2S, mediated vasorelaxation is prevented by the cGMP pathway inhibitors ODQ (sGC inhibitor) and KT5823 (PKG inhibitor) (Online Figure IX). Since charybdotoxin and apamin also inhibit a component of the H2S induced vasorelaxation (Figure 2A), IKCa and SKCa channels may in part mediate the effects of H2S, consistent with the findings of Wang et al..24 The combination of glibenclamide and charybdotoxin/apamin abolishes all H2S-mediated vasorelaxation (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. KCl and glibenclamide markedly diminish H2S vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization in intact and endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries.

(A) H2S (100 µM) vasorelaxation of rat mesenteric arteries is completely blocked by 30 mM KCl, is reduced by 75% with glibenclamide (5 µM) alone, 25% with combination of charybdotoxin (ChTx) (1 µM) and apamin (5 µM) and almost 100% with glibenclamide and ChTx/Apamin. SNP (1 µM) vasorelaxation is not affected by any of the potassium channel inhibitors. n = 20. (B) H2S (100 µM) hyperpolarization of rat mesenteric arteries is completely blocked by 30 mM KCl and is reduced by about 75% with glibenclamide (5 µM). SNP (1 µM) does not induce hyperpolarization. n = 13. (C) H2S (100 µM) vasorelaxation in endothelium-denuded rat mesenteric artery is almost completely abolished by glibenclamide (5 µM), which fails to alter effects of SNP (1 µM). n = 6. (D) H2S hyperpolarizes endothelial cells, as seen in primary cultures of wild-type, but not CSE knockout, mouse aortic endothelial cells stimulated with acetylcholine. Treatment with ChTx/apamin completely abolishes the H2S effect. n = 10. (E) H2S hyperpolarizes human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) treated with Iberiotoxin (0.5 µM) or glibenclamide (0.1 µM), but not TRAM-34 (10 nM). n = 8. All results are mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001).

H2S is generated by CSE in the endothelium of blood vessels, and, like NO, diffuses to the adjacent smooth muscle to elicit vasorelaxation.9 We confirm that the actions of H2S-induced vasorelaxation via the ATP-sensitive potassium channels reflect direct influences upon the vascular smooth muscle, as in endothelium-denuded mesenteric artery, NaHS relaxation is abolished by glibenclamide, which fails to alter effects of NO (Figure 2C). H2S can also hyperpolarize endothelial cells, as primary cultures of wild-type, but not CSE knockout, mouse aortic endothelial cells are hyperpolarized upon acetylcholine stimulation (Figure 2D). This effect is mediated not by ATP-sensitive potassium channels, but by the combination of IKCa/SKCa channels, as hyperpolarization is completely blocked by charybdotoxin/apamin (Figure 2D). In addition, in cultured human endothelial cells (HAECs), H2S-mediated hyperpolarization is unaffected by either glibenclamide or the BKca channel blocker iberiotoxin, but is significantly diminished by the IKca channel blocker TRAM-34 (Figure 2E). We have previously demonstrated that chemical stimulation of endothelial cells with ACh or the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 increases CSE activity.9 Here, we now observe an increase in CSE activity in cultured HAECs following shear stress suggesting that H2S, and hence EDHF activity, can be induced not only by cholinergic means, but also by a physiologic mechanical stimulus (Online Figure X).

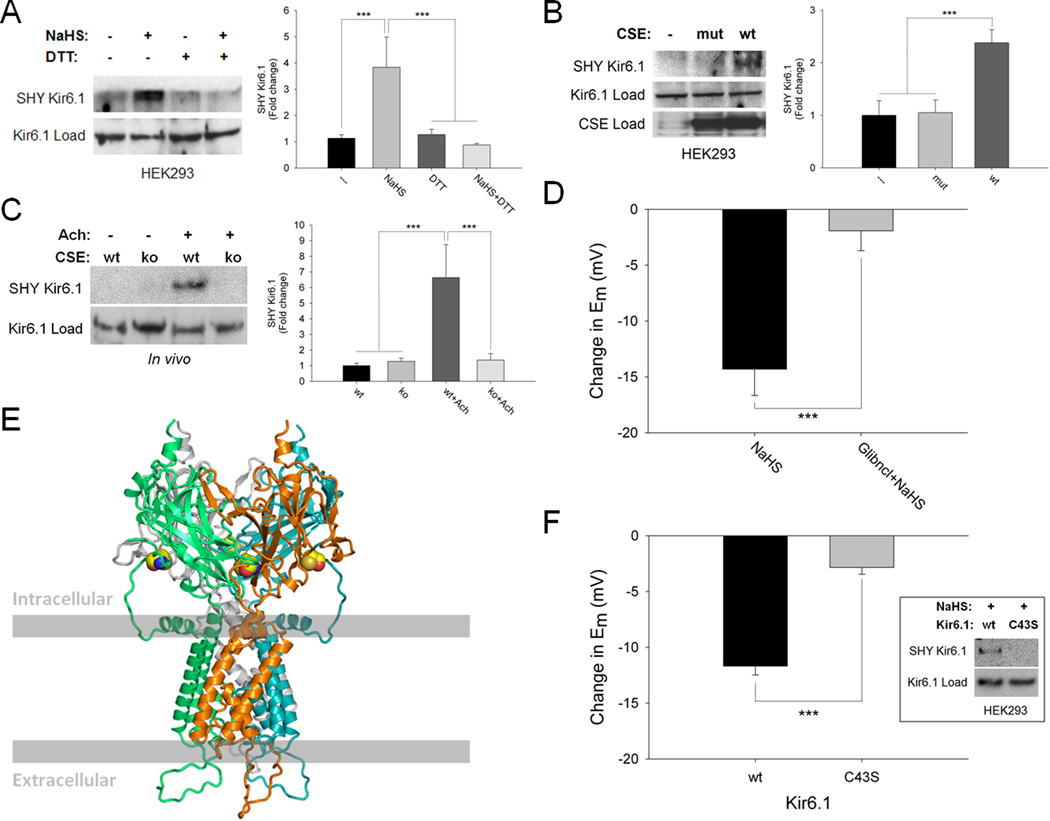

Physiologic sulfhydration of Kir 6.1-C43 activates the channel causing hyperpolarization

Because sulfhydration appears to be a principal means whereby H2S signals,21 we wondered whether vasorelaxation reflects sulfhydration of its target potassium channels. Both the Kir 6.1 subunit of ATP-sensitive potassium channels overexpressed in HEK293 cells and IKca channels from human aortic endothelial cells are sulfhydrated by NaHS in a DTT-sensitive fashion (Figure 3A and Online Figure XI). Kir 6.1 is basally sulfhydrated in cells overexpressing wild-type CSE but not in cells lacking CSE or containing catalytically-inactive CSE (Figure 3B). Cholinergic stimulation of mouse aorta enhances sulfhydration of Kir 6.1 in wild-type but not CSE mutant mice (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Physiologic sulfhydration of Kir 6.1-cysteine-43 activates the channel causing hyperpolarization.

(A) H2S (100 µM) sulfhydrates (SHY) Kir 6.1 overexpressed in HEK293 cells, an effect reversed by DTT (1 mM). n = 4. (B) Kir 6.1 is basally sulfhydrated in cells overexpressing catalytically-active wild-type (wt) CSE but not in cells lacking CSE or containing catalytically-inactive mutant CSE (mut). n = 4. (C) Cholinergic stimulation of mouse aorta enhances sulfhydration of Kir 6.1 in wild-type but not CSE knockout (ko) mice. n = 3. (D) H2S (100 µM)-elicited hyperpolarization in HEK293 cells overexpressing Kir 6.1 is substantially reduced by glibenclamide (5 µM). n = 7. (E) Model of Kir 6.1 homotetramer based on the established structure of Kir 3.1 with surface residue cysteine-43 highlighted in yellow. (F) H2S (300 µM)-mediated sulfhydration (inset) and hyperpolarization are absent in HEK293 cells overexpressing C43S mutant Kir 6.1. n = 12. Quantitative densitometric analysis is also shown for Figure 3A–C. All results are mean ± SEM (***p < 0.001).

To link sulfhydration to channel function, we overexpressed Kir 6.1 in HEK293 cells in which NaHS-elicited hyperpolarization is blocked by glibenclamide, just as in blood vessels (Figure 3D). To identify the sulfhydrated cysteine residue we modeled Kir 6.1 based on the established structure of the highly homologous Kir 3.1 (Figure 3E).26 Kir 6.1 possesses nine cysteines with cysteine-43 (C43), which lies close to the surface, responding selectively to oxidative insults.27 C43 is the principal target of sulfhydration in Kir 6.1, as sulfhydration of the channel is abolished with C43S mutation (Figure 3F inset). NaHS-elicited hyperpolarization is significantly reduced in Kir 6.1-C43S mutants, but responses to the channel opener cromakalim remain preserved (Figure 3F and Online Figure XIIA, B). Thus, H2S vasorelaxation reflects hyperpolarization mediated by the opening of Kir 6.1 channels via their sulfhydration at C43. The channel openers pinacidil and cromakalim elicit hyperpolarization comparable to NaHS in HEK293 cells (Online Figure XIIC).

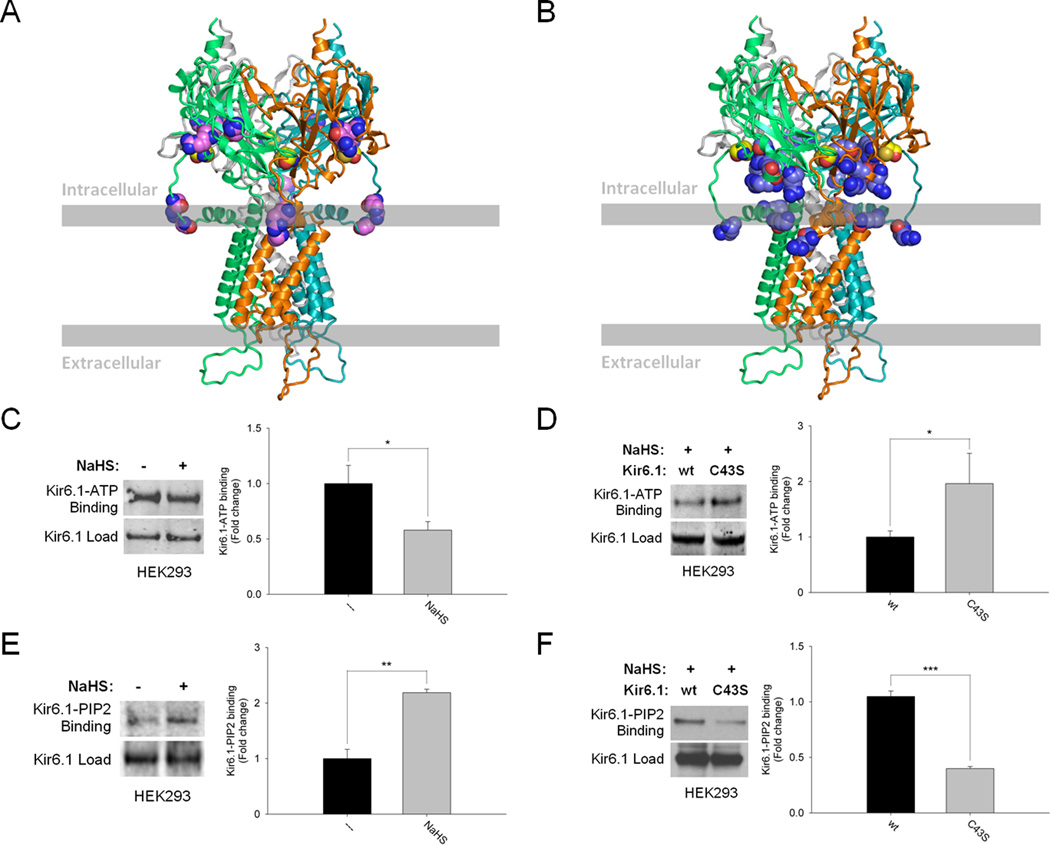

Sulfhydration augments ATP-sensitive potassium channel activity by reducing Kir 6.1-ATP binding and enhancing Kir 6.1-PIP2 binding

Physiologic activation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channels is elicited by binding of its Kir subunits to the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2)28 with concomitant reductions in binding to the inhibitor ATP.29 We wondered whether the regulation by H2S of Kir 6.1 stems from influences on its binding to ATP and PIP2, since cysteine-43 appears to be located within the ATP binding region and adjacent to the PIP2 binding region of Kir channels (Figure 4A, B and Online Figure XIIIA).29–32 In HEK293 cells, NaHS reduces ATP-Kir 6.1 binding (Figure 4C). Confirming that ATP-Kir 6.1 binding involves the sulfhydrated C43, we observe significantly more ATP binding to Kir 6.1-C43S mutants upon treatment with NaHS compared to the wild-type Kir 6.1 (Figure 4D). Unlike its influences on ATP-Kir 6.1 interactions, NaHS markedly augments PIP2-Kir 6.1 binding (Figure 4E). In cells overexpressing wild-type active CSE, PIP2 binds Kir 6.1 with minimal binding in cells lacking CSE or containing the catalytically-inactive enzyme (Online Figure XIV). Finally, we observe substantial reductions of PIP2 binding to Kir 6.1-C43S mutants (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. Sulfhydration augments ATP-sensitive potassium channel activity by reducing Kir 6.1-ATP binding and enhancing Kir 6.1-PIP2 binding.

(A) Model of Kir 6.1 with cysteine-43 highlighted in yellow as well as ATP interacting residues (R51, G54, R195 and R211) highlighted in violet.31, 32 (B) Model of Kir 6.1 with cysteine-43 highlighted in yellow and PIP2 interacting residues (R55, K68, R186, R187, R216 and R310) in stale blue.29, 30 (C) Sulfhydration of Kir 6.1 in HEK293 cells reduces its interaction with ATP. n = 4. (D) Kir 6.1-ATP interaction is substantially enhanced in H2S (100 µM)-treated HEK293 cells overexpressing Kir 6.1-C43S mutant. n = 3. (E) Sulfhydration of Kir 6.1 in HEK293 cells markedly augments its binding to PIP2. n = 3. (F) Kir 6.1-PIP2 interaction is significantly reduced in H2S (100 µM)-treated HEK293 cells overexpressing Kir 6.1-C43S mutant. n = 4. Quantitative densitometric analysis is also shown for Figure 4C–F. All results are mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001).

Discussion

In summary, our findings establish H2S as a principal mediator of EDHF activity, as it satisfies all the major requirements of an EDHF candidate (Online Table I). EDHF activity is virtually abolished in two major vascular beds of CSE deleted mice. EDHF, like H2S, is produced by vascular endothelial cells upon cholinergic stimulation in a calcium-calmodulin dependent manner and both directly activate endothelial potassium channels, hyperpolarizing the cells while diffusing to adjacent smooth muscle cells where they function in a similar capacity.5–7 EDHF appears to function by covalently modifying cysteine residues of its targets, as reducing agents such as DTT reverse its effects.33 H2S also functions by sulfhydrating cysteine residues of key potassium channels in a DTT-sensitive manner. Hyperpolarization of endothelial and smooth muscle cells by H2S and EDHF leads to vasorelaxation that is independent of the NO-cGMP pathway.34 Unlike NO, which signals primarily in larger conductance vessels, EDHF activity is notably predominant in smaller vascular beds, the resistance blood vessels that determine blood pressure.5–7, 34, 35 This fits with our observations of a greater role for H2S in the mesenteric artery, a resistance vessel, than in the aorta, which displays more prominent NO-mediated relaxation. Recently, H2S has been shown to be an important endogenous vasorelaxant in smaller cerebral arteries.36 NO can inhibit the synthesis and release of EDHF,37 which might explain the prominence of EDHF in mesenteric arteries whose levels of eNOS, and therefore NO production, are less compared to the aorta.38 We find that NO can directly inhibit CSE activity in vitro with an IC50 of approximately 100 nM (Online Figure XV).

It is important to note however that mediators beyond EDHF and EDRF do play significant vaso-regulatory roles in different arteries. For example, studies have shown that CO plays an important role in renal vaso-regulation, although the molecular mechanism of which has not entirely been worked-out.39 Endothelial-dependent potassium channel activity does not appear to be involved in guinea-pig uterine artery relaxation.40 H2O2 dilates coronary vasculature through a redox mechanism involving thiol oxidation via p38 map kinase.41 Although the variation in histology and physiology of vessels amongst different species appears to preclude the existence of a universal set of vaso-regulatory molecules, EDHF or EDRF have nonetheless been repeatedly demonstrated to be the principal mechanism by which vascular tone is regulated.

While some studies indicate that circulating H2S levels in the vasculature are less than 1 µM42 there are numerous studies that show much larger concentrations of H2S ranging from 30 to 300 µM in blood vessels as well as in numerous other tissues including the heart, lung, brain, liver and kidney.10, 43–50 Presumably, this generation of H2S by different tissues (particularly the liver) contributes to circulating plasma levels in the 30 to 300 µM range. This may result in perfusion of the entire body with significant H2S concentrations. Our utilization of 100 µM NaHS is in keeping with physiologic concentration of the gas to which blood vessels might well be exposed.

Of the numerous substances that have been explored as potential mediators of EDHF, including potassium ions, lipoxygenase products, hydrogen peroxide, CNP (C-type natriuretic peptide), cytochrome P450 derived EETs and even NO itself,6 there are few studies utilizing mutant mice indicating a physiologic role for them as EDHF mediators. eNOS/COX-1 double knockout mice display reduced endothelial dependent vasodilation, but no significant attenuation of membrane potential change.51 Epoxide hydrolase knockouts manifest elevated EETs and hypotension, but no available membrane potential data support these molecules as EDHF.52 In contrast, the profoundly diminished vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization of CSE knockouts establishes H2S as a major EDHF. It is nonetheless possible that these other EDHF candidates may play important roles in modulating the formation or actions of H2S. As our studies have been confined to rodents, we do not know if they apply fully to human vasculature. However, vascular regulation is generally similar in humans and rodents.5, 7

Sulfhydration is a physiologic modification of cysteines in H2S target proteins analogous to S-nitrosylation by NO.21, 53 S-nitrosylation most often inhibits the function of its targets, while sulfhydration predominantly enhances activity.21, 53 The importance of sulfhydration is indicated by the large proportion of proteins that are sulfhydrated and the considerable extent of sulfhydration, 10 – 25 % for some major liver proteins including actin, β-tubulin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).21 The process of sulfhydration reflects the formation of a persulfide bond, which is an oxidative reaction. H2S is sometimes referred to as a reducing agent. Like many other substances however, the redox potential of H2S enables it to act both as a reducing as well as an oxidizing agent. Some well-known examples of dual role substances are cysteine and glutathione, which despite being recognized as reducing agents, mediate the oxidizing processes of cysteinylation and glutathionylation of proteins respectively.54 These modifications essentially appear to follow a similar chemistry as sulfhydration. This contrasts with substances such as DTT, which are very strong reducing agents and not likely to have oxidizing functions.55

Evidence that Kir 6.1 is physiologically sulfhydrated includes the demonstration of its sulfhydration basally as well as elicited by cholinergic simulation and H2S donors with sulfhydration abolished in CSE deleted tissues. Moreover, we established that sulfhydration involves a single cysteine, cysteine-43, whose mutation abolishes sulfhydration and the subsequent H2S-mediated hyperpolarization. Previously, we demonstrated sulfhydration of several dozen proteins, with the modification confirmed in vivo by mass spectrometry.21 The very low abundance of Kir 6.1 in vascular tissue however renders a mass spectrometric analysis not feasible.

Activation of Kir 6.1 is known to reflect its dissociation with ATP29 and binding to PIP228 which we also observe following sulfhydration at cysteine-43. As sulfhydration renders cysteines more electronegative, the modification at cysteine-43, which lies within the electropositive ATP binding region, might electrostatically hinder channel binding to ATP in addition to causing steric hindrance (Online Figure XIIIB). Since the PIP2 binding region lies adjacent to the ATP binding region, preclusion of ATP binding may provide PIP2 greater access to its binding site on the channel leading to enhanced channel activity.

Several studies suggest that myoendothelial gap junctions composed of connexins transduce endothelial to vascular smooth muscle hyperpolarization.56, 57 Connexin 40 deleted mice, which lack the myoendothelial gap junctions, are hypertensive.56 Furthermore, inhibitors of gap junction attenuate smooth muscle hyperpolarization in rat mesenteric artery but have no effect on endothelial hyperpolarization.57 H2S stimulates endothelial IKca/SKca as well as smooth muscle ATP-sensitive potassium channels leading to hyperpolarization and vasorelaxation (Online Figure XVI). Given the clear implications of gap junctions regulating smooth muscle hyperpolarization, it is likely that H2S diffuses from endothelial to smooth muscle cells via gap junctions to sulfhydrate the cytosolic cysteine-43 of smooth muscle ATP-sensitive potassium channels. These potential mechanisms however remain to be explored.

What are the physiologic and pathophysiologic consequences of these observations? It is clear that deletion of these potassium channels,58 as well as application of potent and selective channel inhibitors such as glibenclamide,59, 60 causes hypertension similar to our earlier observations with CSE deleted animals.9 Recently, Ishii et al. have shown that deletion of CSE does not significantly alter blood pressure in mice.61 It is important to note however that in this instance blood pressure was measured using the tail-cuff method which is not only less precise compared to the more invasive catheter measurements conducted by our laboratories,9 but also leads to highly variable measurements hindering proper analysis of the data. On the other hand, in addition to the data presented here on the CSE inhibitor PPG, there is now clear evidence that selective CSE inhibitors, as well as pathologic conditions such as intermittent hypoxia in which H2S is diminished, significantly increase vascular myogenic tone, and therefore raise blood pressure.62

Thus, the finding that H2S is a major EDHF of resistance blood vessels that regulate blood pressure, as well as its novel mechanism of action may have important therapeutic implications. Drugs altering CSE activity or H2S-mediated channel sulfhydration may be beneficial in treating diverse vascular disorders including hypertension.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) is a gaseous signaling molecule. It is synthesized by cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), which is confined predominantly to the vascular endothelium.

Mice lacking H2S are hypertensive and demonstrate impaired endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation. Thus, H2S acts as an Endothelial Derived Relaxing Factor (EDRF) that mediates vascular relaxation and lowers blood pressure.

The effects of H2S, unlike those of NO, are mediated, in part, by the activation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP); but are independent of cyclic GMP.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

H2S causes a redox sensitive post-translational modification, sulfhydration, of a single cysteine, C43, in the Kir 6.1 subunit of the KATP channel.

H2S-mediated sulfhydration enhances Kir 6.1 activity by reducing Kir 6.1-ATP binding and increasing Kir 6.1-PIP2 binding.

Hence, cholinergic, endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization are significantly reduced in vessels in which CSE is inhibited, in vessels from CSE−/− mice, or in which the KATP channel has been inhibited.

Sulfhydration of the calcium-dependent intermediate conductance potassium channel (IKca) contributes to H2S-dependent hyperpolarization of endothelial cells.

Emerging evidence suggests that H2S is an important gaseous signaling molecule in the vascular system, where it is produced by the endothelial enzyme cystathionine γ-lyase. It mediates vasorelaxation in part by activating vascular smooth muscle KATP channels. We found that cholinergic vasorelaxation and hyperpolarization are markedly reduced in CSE−/− and glibenclamide-treated vessels, indicating that H2S is a major Endothelial Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor (EDHF) that causes vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cell hyperpolarization and vasorelaxation since H2S mediates its effect by a novel redox sensitive thiol-dependent post-translational modification of proteins by sulfhydration. Indeed the Kir 6.1 KATP subunit C43S mutant expressed in HEK293 cells abolishes sulfhydration and significantly reduces H2S mediated hyperpolarization. Sulfhydration of C43 in the Kir 6.1 subunit of the KATP channel reduces ATP binding and enhances PIP2 binding, a process that leads to channel activation. Finally, H2S also leads to sulfhydration and hyperpolarization of endothelial cells through the IKca and SKca channels. These findings suggest that H2S is an important EDHF; therefore, dysregulation of this pathway may be critical step in the development of vascular diseases such as hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Yoshi Kurachi & Hiroshi Hibino (Osaka University, Japan) for providing the SUR2B cDNA construct and Drs. Victor Miriel, David Yue and Manu Ben Johny for advice on the membrane potential experiments.

Sources of Funding

This study has been supported by a NIH National Research Service Award (1 F30 MH074191-01A2) to A.K.M., American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (10POST4010028) to G.S, operating grants of Canadian Institutes of Health Research to R.W, NIH/NHLBI R01 Grant (HL105296-02) to D.E.B. and NIH USPHS grant (MH18501) and Research Scientist Award (DAOOO74) to S.H.S.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- H2S

Hydrogen Sulfide

- NaHS

Sodium Hydrogen Sulfide

- EDHF

Endothelial Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor

- EDRF

Endothelial Derived Relaxing Factor

- CSE

Cystathionine γ-lyase

- IKca

Intermediate conductance potassium channel

- SKca

Small conductance potassium channel

- NOS

Nitric Oxide Synthase

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- L-NAME

L-NG-Nitroarginine methyl ester

- PPG

Propargylglycine

- DiBAC

Bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid)trimethine oxonol

- FLIPR

Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader

- PIP2

Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate

- Em

Membrane potential

- NCI

NOS/COX Inhibitors

- Ach

Acetylcholine

- SNP

Sodium Nitroprusside

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Murad F. Shattuck Lecture. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP in cell signaling and drug development. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 9;355(19):2003–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980 Nov 27;288(5789):373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Dec;84(24):9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncada S, Higgs EA. The discovery of nitric oxide and its role in vascular biology. Br J Pharmacol. 2006 Jan;147 Suppl 1:S193–S201. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feletou M, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizations: past beliefs and present facts. Ann Med. 2007;39(7):495–516. doi: 10.1080/07853890701491000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen RA. The endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor puzzle: a mechanism without a mediator? Circulation. 2005 Feb 15;111(6):724–727. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156405.75257.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith TM. Endothelium-dependent smooth muscle hyperpolarization: do gap junctions provide a unifying hypothesis? Br J Pharmacol. 2004 Mar;141(6):881–903. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Bubolz AH, Mendoza S, Zhang DX, Gutterman DD. H2O2 is the transferrable factor mediating flow-induced dilation in human coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 2011 Mar 4;108(5):566–573. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008 Oct 24;322(5901):587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. Embo J. 2001 Nov 1;20(21):6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Nagahara N, Kimura H. Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide. J Biochem. 2009 Nov;146(5):623–626. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang PL, Huang Z, Mashimo H, Bloch KD, Moskowitz MA, Bevan JA, Fishman MC. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995 Sep 21;377(6546):239–242. doi: 10.1038/377239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers RW, Gandley RE, Lykins DL, Roberts JM. Moderate hyperhomocysteinemia decreases endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation in pregnant but not nonpregnant mice. Hypertension. 2004 Sep;44(3):327–333. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000137414.12119.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao W, Wang R. H(2)S-induced vasorelaxation and underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002 Aug;283(2):H474–H480. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chotani MA, Flavahan S, Mitra S, Daunt D, Flavahan NA. Silent alpha(2C)-adrenergic receptors enable cold-induced vasoconstriction in cutaneous arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000 Apr;278(4):H1075–H1083. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winters B, Mo Z, Brooks-Asplund E, Kim S, Shoukas A, Li D, Nyhan D, Berkowitz DE. Reduction of obesity, as induced by leptin, reverses endothelial dysfunction in obese (Lep(ob)) mice. J Appl Physiol. 2000 Dec;89(6):2382–2390. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.6.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whiteaker KL, Gopalakrishnan SM, Groebe D, Shieh CC, Warrior U, Burns DJ, Coghlan MJ, Scott VE, Gopalakrishnan M. Validation of FLIPR membrane potential dye for high throughput screening of potassium channel modulators. J Biomol Screen. 2001 Oct;6(5):305–312. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleem F, Rowe IC, Shipston MJ. Characterization of BK channel splice variants using membrane potential dyes. Br J Pharmacol. 2009 Jan;156(1):143–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baczko I, Giles WR, Light PE. Pharmacological activation of plasma-membrane KATP channels reduces reoxygenation-induced Ca(2+) overload in cardiac myocytes via modulation of the diastolic membrane potential. Br J Pharmacol. 2004 Mar;141(6):1059–1067. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaffrey SR, Snyder SH. The biotin switch method for the detection of S-nitrosylated proteins. Sci STKE. 2001 Jun 12;2001(86):pl1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.86.pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, Snyder SH. H2S Signals Through Protein S-Sulfhydration. Sci Signal. 2009;2(96):ra72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boo YC, Sorescu G, Boyd N, Shiojima I, Walsh K, Du J, Jo H. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at Ser1179 by Akt-independent mechanisms: role of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2002 Feb 1;277(5):3388–3396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin J, Jo H, Park H. Caveolin-1 is transiently dephosphorylated by shear stress-activated protein tyrosine phosphatase mu. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006 Jan 20;339(3):737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng Y, Ndisang JF, Tang G, Cao K, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide-induced relaxation of resistance mesenteric artery beds of rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004 Nov;287(5):H2316–H2323. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00331.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Standen NB, Quayle JM, Davies NW, Brayden JE, Huang Y, Nelson MT. Hyperpolarizing vasodilators activate ATP-sensitive K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle. Science. 1989 Jul 14;245(4914):177–180. doi: 10.1126/science.2501869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishida M, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of a Kir3.1-prokaryotic Kir channel chimera. Embo J. 2007 Sep 5;26(17):4005–4015. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trapp S, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. Mechanism of ATP-sensitive K channel inhibition by sulfhydryl modification. J Gen Physiol. 1998 Sep;112(3):325–332. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilgemann DW, Feng S, Nasuhoglu C. The complex and intriguing lives of PIP2 with ion channels and transporters. Sci STKE. 2001 Dec 4;2001(111):re19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.111.re19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baukrowitz T, Schulte U, Oliver D, Herlitze S, Krauter T, Tucker SJ, Ruppersberg JP, Fakler B. PIP2 and PIP as determinants for ATP inhibition of KATP channels. Science. 1998 Nov 6;282(5391):1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haider S, Tarasov AI, Craig TJ, Sansom MS, Ashcroft FM. Identification of the PIP2-binding site on Kir6.2 by molecular modelling and functional analysis. Embo J. 2007 Aug 22;26(16):3749–3759. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribalet B, John SA, Xie LH, Weiss JN. Regulation of the ATP-sensitive K channel Kir6.2 by ATP and PIP(2) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005 Jul;39(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koster JC, Kurata HT, Enkvetchakul D, Nichols CG. DEND mutation in Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) reveals a flexible N-terminal region critical for ATP-sensing of the KATP channel. Biophys J. 2008 Nov 15;95(10):4689–4697. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.138685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNeish AJ, Wilson WS, Martin W. Ascorbate blocks endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF)-mediated vasodilatation in the bovine ciliary vascular bed and rat mesentery. Br J Pharmacol. 2002 Apr;135(7):1801–1809. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagao T, Illiano S, Vanhoutte PM. Heterogeneous distribution of endothelium-dependent relaxations resistant to NG-nitro-L-arginine in rats. Am J Physiol. 1992 Oct;263(4 Pt 2):H1090–H1094. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urakami-Harasawa L, Shimokawa H, Nakashima M, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Importance of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in human arteries. J Clin Invest. 1997 Dec 1;100(11):2793–2799. doi: 10.1172/JCI119826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leffler CW, Parfenova H, Basuroy S, Jaggar JH, Umstot ES, Fedinec AL. Hydrogen sulfide and cerebral microvascular tone in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011 Feb;300(2):H440–H447. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00722.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauersachs J, Popp R, Hecker M, Sauer E, Fleming I, Busse R. Nitric oxide attenuates the release of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circulation. 1996 Dec 15;94(12):3341–3347. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimokawa H, Yasutake H, Fujii K, Owada MK, Nakaike R, Fukumoto Y, Takayanagi T, Nagao T, Egashira K, Fujishima M, Takeshita A. The importance of the hyperpolarizing mechanism increases as the vessel size decreases in endothelium-dependent relaxations in rat mesenteric circulation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996 Nov;28(5):703–711. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199611000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Pascoli M, Zampieri F, Quarta S, Sacerdoti D, Merkel C, Gatta A, Bolognesi M. Heme oxygenase regulates renal arterial resistance and sodium excretion in cirrhotic rats. J Hepatol. 2011 Feb;54(2):258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jovanovic A, Grbovic L, Jovanovic S. K+ channel blockers do not modify relaxation of guinea-pig uterine artery evoked by acetylcholine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995 Jun 23;280(1):95–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00236-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saitoh S, Kiyooka T, Rocic P, Rogers PA, Zhang C, Swafford A, Dick GM, Viswanathan C, Park Y, Chilian WM. Redox-dependent coronary metabolic dilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 Dec;293(6):H3720–H3725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00436.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitfield NL, Kreimier EL, Verdial FC, Skovgaard N, Olson KR. Reappraisal of H2S/sulfide concentration in vertebrate blood and its potential significance in ischemic preconditioning and vascular signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008 Jun;294(6):R1930–R1937. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han Y, Qin J, Chang X, Yang Z, Du J. Hydrogen sulfide and carbon monoxide are in synergy with each other in the pathogenesis of recurrent febrile seizures. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006 Feb;26(1):101–107. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-8848-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhong G, Chen F, Cheng Y, Tang C, Du J. The role of hydrogen sulfide generation in the pathogenesis of hypertension in rats induced by inhibition of nitric oxide synthase. J Hypertens. 2003 Oct;21(10):1879–1885. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200310000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell TW, Savage JC, Gould DH. High-performance liquid chromatography detection of sulfide in tissues from sulfide-treated mice. J Appl Toxicol. 1993 Nov–Dec;13(6):389–394. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogasawara Y, Isoda S, Tanabe S. Tissue and subcellular distribution of bound and acid-labile sulfur, and the enzymic capacity for sulfide production in the rat. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994 Dec;17(12):1535–1542. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorman DC, Moulin FJ, McManus BE, Mahle KC, James RA, Struve MF. Cytochrome oxidase inhibition induced by acute hydrogen sulfide inhalation: correlation with tissue sulfide concentrations in the rat brain, liver, lung, and nasal epithelium. Toxicol Sci. 2002 Jan;65(1):18–25. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodwin LR, Francom D, Dieken FP, Taylor JD, Warenycia MW, Reiffenstein RJ, Dowling G. Determination of sulfide in brain tissue by gas dialysis/ion chromatography: postmortem studies and two case reports. J Anal Toxicol. 1989 Mar–Apr;13(2):105–109. doi: 10.1093/jat/13.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savage JC, Gould DH. Determination of sulfide in brain tissue and rumen fluid by ion-interaction reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1990 Apr 6;526(2):540–545. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warenycia MW, Goodwin LR, Benishin CG, Reiffenstein RJ, Francom DM, Taylor JD, Dieken FP. Acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Demonstration of selective uptake of sulfide by the brainstem by measurement of brain sulfide levels. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989 Mar 15;38(6):973–981. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scotland RS, Madhani M, Chauhan S, Moncada S, Andresen J, Nilsson H, Hobbs AJ, Ahluwalia A. Investigation of vascular responses in endothelial nitric oxide synthase/cyclooxygenase-1 double-knockout mice: key role for endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in the regulation of blood pressure in vivo. Circulation. 2005 Feb 15;111(6):796–803. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155238.70797.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinal CJ, Miyata M, Tohkin M, Nagata K, Bend JR, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of soluble epoxide hydrolase reveals a role in blood pressure regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000 Dec 22;275(51):40504–40510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Feb;6(2):150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michelet L, Zaffagnini M, Massot V, Keryer E, Vanacker H, Miginiac-Maslow M, Issakidis-Bourguet E, Lemaire SD. Thioredoxins, glutaredoxins, and glutathionylation: new crosstalks to explore. Photosynth Res. 2006 Sep;89(2–3):225–245. doi: 10.1007/s11120-006-9096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kabil O, Banerjee R. Redox biochemistry of hydrogen sulfide. J Biol Chem. 2010 Jul 16;285(29):21903–21907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.128363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Wit C, Roos F, Bolz SS, Kirchhoff S, Kruger O, Willecke K, Pohl U. Impaired conduction of vasodilation along arterioles in connexin40-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2000 Mar 31;86(6):649–655. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sandow SL, Tare M, Coleman HA, Hill CE, Parkington HC. Involvement of myoendothelial gap junctions in the actions of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circ Res. 2002 May 31;90(10):1108–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000019756.88731.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miki T, Suzuki M, Shibasaki T, Uemura H, Sato T, Yamaguchi K, Koseki H, Iwanaga T, Nakaya H, Seino S. Mouse model of Prinzmetal angina by disruption of the inward rectifier Kir6.1. Nat Med. 2002 May;8(5):466–472. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yosefy C, Magen E, Kiselevich A, Priluk R, London D, Volchek L, Viskoper RJ., Jr Rosiglitazone improves, while Glibenclamide worsens blood pressure control in treated hypertensive diabetic and dyslipidemic subjects via modulation of insulin resistance and sympathetic activity. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004 Aug;44(2):215–222. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200408000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmitt JK, Moore JR. Hypertension secondary to chlorpropamide with amelioration by changing to insulin. Am J Hypertens. 1993 Apr;6(4):317–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ishii I, Akahoshi N, Yamada H, Nakano S, Izumi T, Suematsu M. Cystathionine gamma-Lyase-deficient mice require dietary cysteine to protect against acute lethal myopathy and oxidative injury. J Biol Chem. 2010 Aug 20;285(34):26358–26368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson-Weaver O, Paredes DA, Gonzalez Bosc LV, Walker BR, Kanagy NL. Intermittent hypoxia in rats increases myogenic tone through loss of hydrogen sulfide activation of large-conductance Ca(2+)-activated potassium channels. Circ Res. 2011 Jun 10;108(12):1439–1447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.