Abstract

Large egg size usually boosts offspring survival, but mothers have to trade off egg size against egg number. Therefore, females often produce smaller eggs when environmental conditions for offspring are favourable, which is subsequently compensated for by accelerated juvenile growth. How this rapid growth is modulated on a molecular level is still unclear. As the somatotropic axis is a key regulator of early growth in vertebrates, we investigated the effect of egg size on three key genes belonging to this axis, at different ontogenetic stages in a mouthbrooding cichlid (Simochromis pleurospilus). The expression levels of one of them, the growth hormone receptor (GHR), were significantly higher in large than in small eggs, but remarkably, this pattern was reversed after hatching: young originating from small eggs had significantly higher GHR expression levels as yolk sac larvae and as juveniles. GHR expression in yolk sac larvae was positively correlated with juvenile growth rate and correspondingly fish originating from small eggs grew faster. This enabled them to catch up fully in size within eight weeks with conspecifics from larger eggs. This is the first evidence for a potential link between egg size, an important maternal effect, and offspring gene expression, which mediates an adaptive adjustment in a relevant hormonal axis.

Keywords: maternal effects, egg size, gene expression, compensatory growth, somatotropic axis, fish

1. Introduction

There is abundant evidence that females can contribute to the early offspring environment through maternal effects and can thereby influence the survival prospects of offspring [1–5]. Maternal effects are often passed on by the properties of eggs [6,7], and among these, egg size has received by far the greatest attention [8–13]. Egg size is not only easy to quantify, but also often reflects the amount of resources mothers invest in individual offspring [14,15]. Females must trade off an increased egg size against the number of eggs they can produce [16] and hence benefit from producing an egg size that maximizes their fitness in a given environment [9]. It is therefore not surprising that egg size often highly varies both between females of a species and between clutches of the same individual [8,12].

Most often, larger eggs result in larger offspring [17,18]. Size and growth is considered to be particularly important in early life-history stages as juveniles may benefit from reaching size refuges from competition [19], winter-mortality [20] and negative size-selective predation [21]. Therefore, we can expect that hatching from different egg sizes gives rise to different growth trajectories as a result of differentiation in the activity of genes involved in growth. For example, offspring hatched from smaller eggs often grow faster than offspring from larger eggs, and are thereby capable to catch up in size with the latter [22–27], or even overcompensate, so that they reach larger body sizes than offspring hatched from large eggs [28].

Although many studies stress that individual differences in growth are crucial for juvenile survival, so far the underlying molecular mechanisms that regulate growth compensation in juveniles hatched from small eggs have not been explored. A large variation in gene expression among eggs has been reported previously [29], but this study did not explore the possible link between maternal effects and gene expression. Moreover, no one has yet examined how egg-trait-induced differences in gene expression affect offspring phenotype. Hence, the ecological consequences of differential gene expression mediated by maternal effects are unknown.

The somatotropic axis is a key regulator of embryonic and postnatal growth in vertebrates, which makes it a candidate mediator of maternal regulation of offspring growth performance. In this axis, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) mediates many growth hormone (GH) effects both as a circulating hormone and as a locally produced growth factor [30,31]. GH is postnatally produced by the pituitary and is the major regulator of growth in vertebrates. Cellular effects of GH are initiated by binding to GHR, a class I cytokine receptor, which triggers the JAK2-STAT signalling cascade leading to the transcriptional activation of mitogenic factors, such as IGF-1 [30]. GHR, IGF-1 and IGF-2 are all widely produced during embryonic development in fishes and in other vertebrates [32–34].

In this study, we investigate the link between egg size and the expression of genes involved in the control of somatic growth. At the same time, we explore the possible ecological function of gene expression variation in the mouthbrooding cichlid Simochromis pleurospilus. We compared gene expression in clutches consisting of either large or small eggs at four stages during early development: within 1 day after fertilization, at an age of 2 days, at the yolk sac stage (age of 8 days) and as juvenile (age of 38 days). At each stage, we compared the transcription levels of growth hormone receptor (GHR) and IGF-1 and IGF-2 in siblings of representative clutches. Subsequently, we tested for an association between differently expressed genes and the growth of juveniles. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating if gene expression might be linked to maternal investment and if egg size-induced differences in gene expression may affect offspring phenotype.

2. Methods

(a). Study species and animal husbandry

Simochromis pleurospilus is a maternally mouthbrooding cichlid endemic to Lake Tanganyika, one of the Great Lakes of East Africa. Females incubate their young for about two weeks in the mouth while the larvae consume their yolk sac, followed by a two week period in which the mother releases the young regularly for foraging [35]. Our laboratory stock originates from a population at the southern tip of the lake near Nkumbula Island, Zambia. The juveniles used for the experiment were third generation descendants from wild caught individuals. To obtain clutches, we placed groups of 4–15 females together with 1–5 males in 200 l and 400 l tanks. All fish are kept at a 13 : 11 h L : D regime and at water temperatures of 26.0–28.0°C. The adults were fed twice daily with TetraMin flakes and once a week with a mixture of small, frozen crustaceans. All tanks were equipped with a layer of fine grain sand, biological filters, and flower pot halves, which served as shelters.

(b). Experimental design

Twice daily we checked for females with eggs in their mouths to obtain the approximate time of spawning. As soon as possible after fertilization, the eggs were taken from the females by slightly pressing their cheeks. A female was fin-clipped before she was placed back in her group tank to prevent us from taking more than one clutch of the same female. All eggs were weighed individually on an electronic balance to the nearest 0.1 mg. Before weighing, the eggs were placed on a moistened cotton pad so that excess water could run off the egg. We selected clutches for this study with a mean egg weight smaller than 17.0 mg (‘small eggs’) and larger than 19.0 mg (‘large eggs’). Egg size variance is larger between clutches than within clutches in S. pleurospilus (F. H. I. D. Segers & B. Taborsky 2011, unpublished data). As a result, all eggs from a clutch fell in the same size class in all cases. As it was impossible to manipulate egg size in these fish, we collected clutches with large and small eggs from different females, making it impossible to control for maternal genetic background (see §4). In most cases, multiple clutches were collected from the same breeding tank. Often, clutches from the same breeding tank fell in both egg size classes (see electronic supplementary material, table S1), indicating that egg size and the corresponding gene expression pattern were not simply caused by a tank effect. In addition, we corrected for breeding tank in our statistical models (see below) to exclude any confounding tank effects.

We collected 17 clutches in the small egg size class with a range of 11.0–16.9 mg and 13 clutches in the large egg size class with a range of 19.9–25.8 mg mean egg weight. This represents the outer ends of the long-term egg-size distribution observed in our laboratory population of S. pleurospilus (i.e. 7.7–25.8 mg, with egg sizes below 11.0 mg being rare).

We randomly sampled one egg or hatchling per clutch at four stages during early ontogeny, whereas the remaining siblings were raised to obtain further growth measurements. Sample 1 was taken within 24 h of fertilization and always immediately after weighing the eggs. We placed one egg in RNAlater (Ambion, USA) and left it overnight at −4°C. The next day, we transferred the sample to a freezer where it was stored at −20°C until analysis. The remaining eggs were hatched in a self-constructed cichlid egg tumbler designed to raise individual eggs (for methods see [18]). Sample 2 was taken approximately 48 h after fertilization. The egg was preserved as described for the first sample. We noted the time to hatch of the remaining eggs, which takes approximately 5 days in S. pleurospilus. On day 8 after fertilization, we sampled one yolk sac larva (sample 3). Before preservation, we measured the total length of the larvae under a binocular with a measuring eye piece. Larvae were anaesthetized in MS-222 (Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland), sacrificed and immediately preserved as described above for the eggs. The next day the remaining hatchlings were placed in a net cage (16.5 × 12 × 13.5 cm) that was fixed at the surface of a 25 l tank. From then on, the fish were exposed to our general husbandry conditions (see above). The number of siblings that survived the egg tumbler varied between clutches (see electronic supplementary material, table S1), but did not differ between egg size classes (t-test, t = 0.79, NS = 13, NcsL = 10, p = 0.43). No juveniles died after they were removed from the egg tumbler, apart from the individuals we sampled for the gene expression analysis. On day 14 after fertilization (corresponding to the age when mothers start releasing young periodically for foraging), we released the young into the 25 l tank and fed them 6 days a week ad libitum with TetraMin flakes. Food remains were removed regularly to prevent the deterioration of water quality. Sample 4 was taken on day 38 after fertilization. This sampling age was chosen because our previous experiments showed that compensatory growth occurs during this life stage [18].

On days 28, 42 and 56 after fertilization, we measured the standard length to the nearest 0.1 mm under a binocular microscope of the siblings that had not been sampled for gene expression analysis. We took the mean of these measurements for each clutch to calculate the specific growth rate (SGR) from day 28 to 56 as follows:

where x1, x2, age1 and age2 are initial and final mean standard lengths and corresponding ages of the fish at two successive measurements.

(c). RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Gene expression was measured using the whole organism. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Merelbeke, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In short, the samples preserved in RNAlater were homogenized in 100 µl TRIzol using TissueLyser II (Quiagen) homogenizer with glass beads. RNA was precipitated by 50 per cent isopropanol, washed with ethanol and air dryed. The pellet was resuspended in RNase-free water and quantified by photospectrometry. DNase digestion was performed with 1 U of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Catalys AG, Switzerland). Single stranded cDNA was synthesized from 800 ng total RNA using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) according to manufacturer's instructions in total amount of 80 µl. Two microlitres of this cDNA was subjected, in triplicates, to real-time PCR using FastStart Universal Probe Master (Rox) (Roche, Switzerland) with the addition of 300 nM of each primer and 150 nM of the fluorogenic probe. Amplification was performed in a reaction volume of a 10 µl in MicroAmp Fast Optical 96-Well Reaction Plate (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Real-time PCR runs were carried out using ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min of the enzyme activation followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

(d). Design of primers and probes for quantitative real-time PCR

Available sequences from related African cichlids were used to create TaqMan real-time PCR assays for the genes in consideration (see electronic supplementary material, table S2). TaqMan probes were labelled at the 5′ end with fluorescent reporter dye fluorescein (FAM) and at the 3′ end with the quencher TAMRA. We investigated the expression of three key genes of the GH–IGF axis, namely GHR, IGF-1 and IGF-2 (see electronic supplementary material, table S2), but we did not include GH as GH transcripts were not detected outside the pituitary neither in S. pleurospilus (this study) nor in another cichlid fish, Oreochromis niloticus [36]. Three housekeeping genes were tested as references for the quantification: ribosomal 18S (R18S, Oreochromis mossambicus), β-Actin (O. niloticus) and the elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1α, O. niloticus). A comparison of these three reference genes showed that R18S has the most stable expression pattern across the experimental groups. Therefore, R18S was chosen as a reference for qPCR data normalization. The target genes were: GHR 1 (O. niloticus), IGF-1 (O. niloticus), and IGF-2 (O. niloticus).

(e). Relative quantification of treatment effects

Differences in gene expression between small and large egg classes were evaluated using the relative gene expression model (ΔΔCT method) [37]. Prior to analysis, amplification efficiencies of all qPCR assays were validated by plotting of CT values of the dilution series of the DNA template against the logarithms of the dilution factors. Comparison of the slopes confirmed that the efficiencies of the compared assays were very similar [38]. Statistical analysis was performed on the ΔCT values of each sample, and the data distribution is presented as a scatter plot of these values. As a higher ΔCT value means a lower expression of a given gene, the axes of the plots were reversed for clarity in the presentations. Relative gene expression ratios (R) were calculated using the formula: R = 2−ΔΔCT with ΔCT = CT (target gene)−CT (reference gene), with ΔΔCT = ΔCT (large egg class)−ΔCT (small egg class). Thus, the reported R values represent n-fold ratios of gene expression levels between small and large egg classes (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1). In some samples, the gene expression analysis failed for unknown reasons, and we ended up with varying sample sizes for the analysis of the three target genes (see electronic supplementary material, table S1).

(f). Statistical analysis

All analyses were done in R v. 2.9.2 [39]. Exploratory data analysis revealed that the variance in gene expression among the samples collected within day 1 after fertilization (sample 1) was high compared to the other sampling days for all three genes (see §3). Therefore, we analysed sample 1 separately: gene expression levels of large and small eggs were compared with a general linear mixed-effects (LME) model, with breeding tank as a random effect to control for non-independence. To test for an effect of egg size and sampling day on gene expression among samples 2, 3 and 4, we used an LME, with clutch nested within breeding tank (see electronic supplementary material, table S1) as a random effect term. The interaction between egg size class and sampling day was tested by fitting two models, one with and one without the interaction, and subsequently comparing the two models using a likelihood ratio test [40]. Non-significant interactions were removed from the model. The effect of egg size on larva length was tested using an LME model with breeding tank as a random effect. The effect of egg size on juvenile growth was tested using LME models with clutch nested within breeding tank as random effect term and with experimental day as a continuous variable. We adjusted significance levels using the sequential Bonferroni correction when we did multiple pairwise comparisons. All significant p-values remained significant after correction. The relationships between the expression levels of the three considered genes and between gene expression and growth were explored by Spearman rank correlations.

3. Results

(a). Gene expression

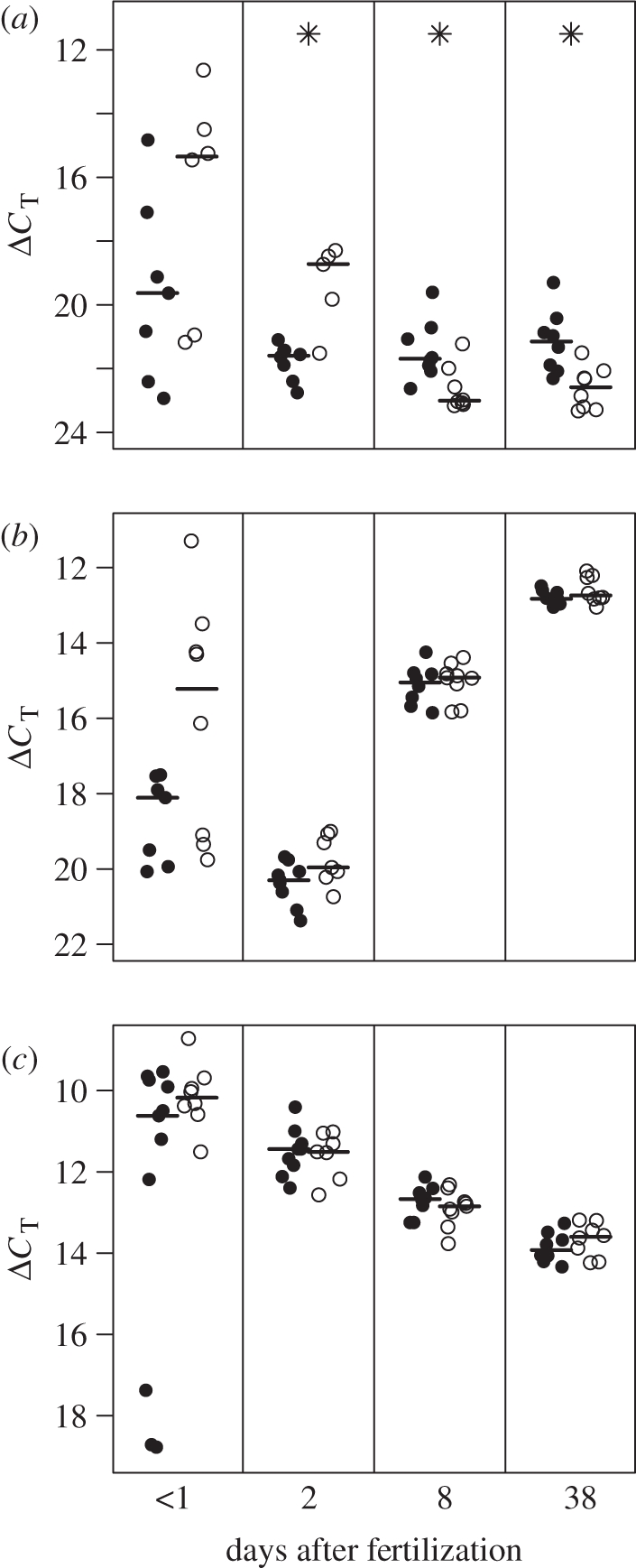

In the sample collected within one day after fertilization (sample 1), expression levels did not differ between the large and the small egg size classes for GHR (LME, n = 13, t = −1.62 p = 0.17), IGF-1 (LME, n = 15, t = −2.14, p = 0.07) or IGF-2 (LME, n = 19, t = −1.32, p = 0.22). It is noteworthy that mRNA quantities were highly variable in this sample for all three genes (figure 1a–c). This variance may largely result from the fact that the interval between spawning (i.e. fertilization) and sampling of eggs varied considerably (range: 2.0–26.5 h), and thus embryonic transcription might have started already in some eggs, but not in others.

Figure 1.

Results of the mRNA quantification of (a) GHR, (b) IGF-1 and (c) IGF-2. The four panels of each graph represent samples taken at days 1, 2, 8 and 38 after fertilization, from left to right. Filled circles: small-egg size class; open circles: large-egg size class; horizontal lines show the medians. Significant differences in gene transcription levels between egg size classes are indicated by asterisks. Note that a higher ΔCT value means a lower expression of a given gene.

There was a significant decrease in GHR expression with sampling day for the hatchlings from large eggs (LME, N = 45, egg size class × sampling day: L = 33.13, p < 0.001). This resulted in large eggs having a higher level of GHR gene transcription than small eggs on day 2, while on day 8 and day 38 (thus after hatching), juveniles from small eggs had a higher GHR gene transcription than juveniles from large eggs (pairwise comparisons, t = −4.92, p = 0.004, t = 2.84, p = 0.01 and t = 3.40, p = 0.005, respectively). Sampling day as a main effect was not significant (pairwise comparisons, all p > 0.10).

Overall, IGF-1 expression tended to be higher in large eggs than in small eggs (LME, n = 49, t = −2.14, p = 0.052; figure 1b). IGF-1 expression increased with sampling day (pairwise comparisons, day 2 versus 8: t = −30.77, p < 0.001 and day 8 versus 38: t = −14.68, p < 0.001), but this increase did not differ between egg size classes (egg size class × sampling day: L = 2.61, p = 0.27).

There was no effect of egg size class on IGF-2 expression (LME, n = 49, egg size class: t = 0.09, p = 0.93 and egg size class × sampling day: L = 1.66, p = 0.44; figure 1c). Overall IGF-2 transcription decreased with sampling day (pairwise comparisons, day 2 versus 8: t = 7.84, p < 0.001 and day 8 versus 38: t = 5.91, p < 0.001).

As GHR signalling influences IGF-1 and IGF-2 transcription in fish [41–43], we examined the correlations between the expression levels of GHR and IGFs. In both samples taken before hatching, the quantities of GHR and IGF-1 mRNA were positively correlated (sample 1: n = 13, rs = 0.75, p = 0.005; sample 2: n = 13, rs = 0.72, p = 0.005). In contrast, after hatching the relationship between the expression levels of the two genes had vanished (sample 3: n = 16, rs = 0.06, p = 0.83; sample 4: n = 16, rs = 0.25, p = 0.34). The expression levels of GHR and IGF-2 were not correlated on any of the sampling days (sample 1: n = 12, rs = −0.02, p = 0.96; sample 2: n = 13, rs = −0.02, p = 0.95; sample 3: n = 16, rs = 0.28, p = 0.30; sample 4: n = 16, rs = 0.06, p = 0.83).

(b). Growth

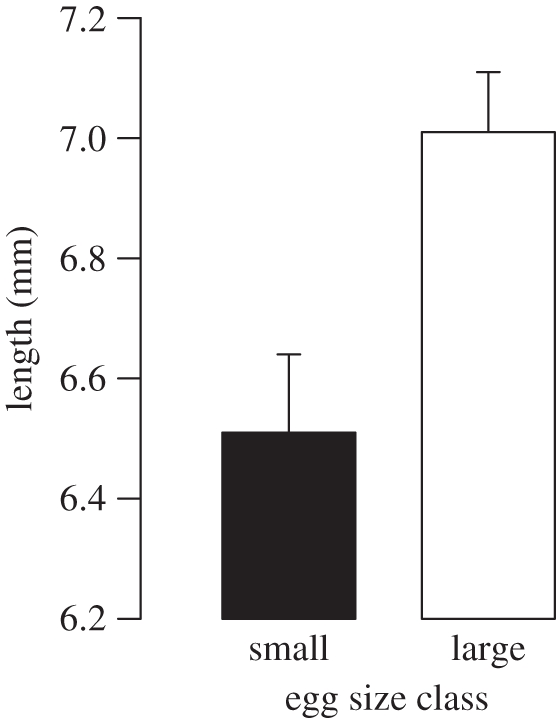

On day 8 after fertilization larvae hatched from large eggs were significantly larger than larvae hatched from small eggs (LME, n = 24, t = 3.08, p = 0.008; figure 2). Because of the considerable noise in the gene expression data of sample 1 (see above), we did not test for relationships between gene expression levels in this sample and later larval size or growth. Two days after spawning (sample 2), gene expression levels in the eggs were not related to body size of larvae from the same clutch on day 8 after fertilization for either GHR (n = 10, rs = −0.18, p = 0.62), IGF-1 (n = 12, rs = 0.37, p = 0.21) or IGF-2 (n = 12, rs = 0.01, p = 0.96).

Figure 2.

Mean total length of larvae + s.e. at day 8 after fertilization.

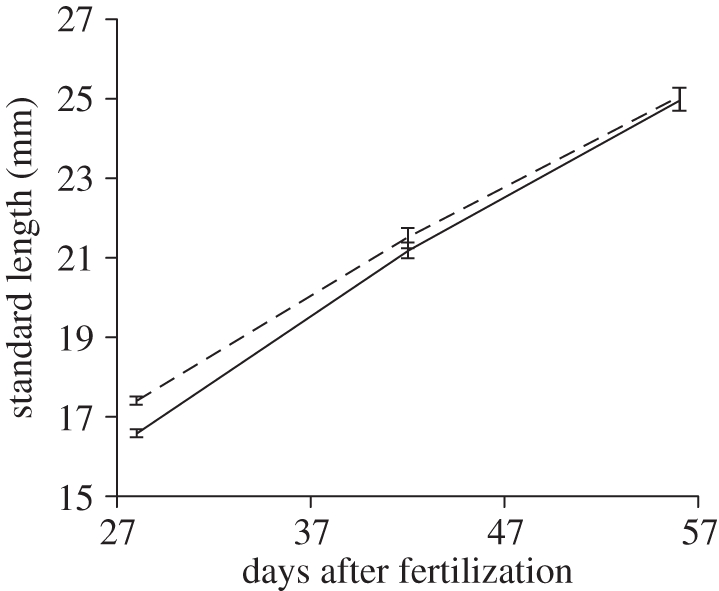

We monitored juvenile growth between day 28 and 56 after fertilization. At the beginning of this period, the juveniles from large-egg clutches were significantly larger than those from small-egg clutches (LME, n = 207, egg size class: t = 2.87, p = 0.01). Naturally, both groups increased in size during this period (LME, n = 207, experimental day: t = 51.82, p < 0.001). However, the small egg size class grew significantly faster (experimental day × egg size class: L = 4.07, p = 0.04; figure 3). Consequently, there was no significant difference in size between juveniles from large and small eggs at day 56 after fertilization (LME, n = 55, t = 0.75, p = 0.47).

Figure 3.

Growth trajectory for juvenile standard length. The mean ± s.e. of the small egg size class and the large egg size class are shown by the solid and the dashed line, respectively.

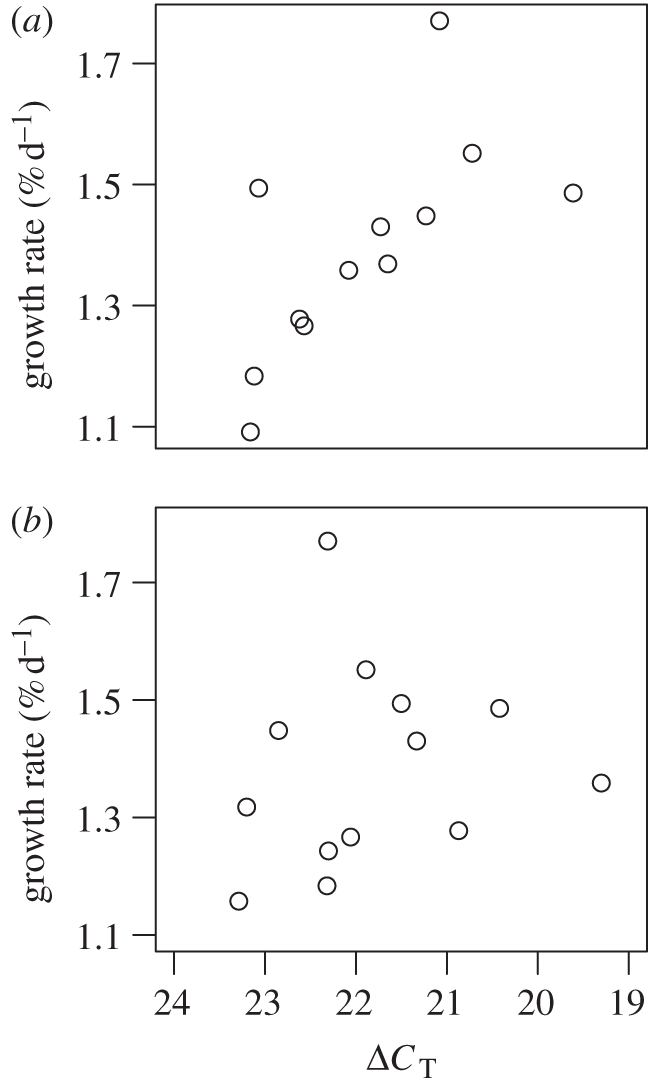

As gene expression levels differed between egg sizes only for the GHR gene, we restricted our analysis to this gene when testing for a relationship between expression levels and growth. GHR expression on day 8 after fertilization (as measured in one sibling per clutch) was positively correlated with the growth rate of the remaining siblings between day 28 and day 56 (n = 12, rs = −0.66, p = 0.007; figure 4a). In contrast, GHR expression levels on day 38 after fertilization were not related to sibling growth rates between 28 and 56 days of age (n = 13, rs = −0.35, p = 0.25; figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Relationship between GHR gene expression level of an individual on (a) day 8 and (b) day 38 and the mean growth rate of its siblings between day 28 and 56 after fertilization.

4. Discussion

Fish hatched from small eggs expressed higher levels of GHR and grew faster, which enabled them to catch up in body size with conspecifics hatched from large eggs within 8 weeks after fertilization. These results suggest that differences in maternal egg provisioning can mediate differential gene expression programmes in offspring. This study is the first to investigate if differences in gene expression are associated with variance in egg size. Moreover, our growth results suggest an ecological function of the differences in gene expression [44], namely, that it allows young to compensate during early ontogeny for a lower maternal investment in egg size.

Interestingly, of the three genes of the somatotropic axis analysed in this study, only GHR mRNA levels differed with egg size, suggesting an IGF-independent action of GH. The binding of GH to its receptor leads to an increase in GHR density and subsequent increase in cellular sensitivity for GH, which can then promote enhanced growth [45,46]. Previously a strong association between the transcription of GHR and IGF-1 was detected, suggesting that a higher GHR density may mediate a higher IGF-1 transcription [46]. In our samples, the expression of GHR and IGF-1 was only significantly correlated at the two sampling stages taken before the hatching of the larvae. Although IGF-1 is considered to be the main mediator of somatotropic actions of GH [31], IGF-1-independent GH function has also been characterized [47]. One of the effects of GH is the ability to promote lipid metabolism [48]. Interestingly, this function of GH is independent as well as antagonistic to the lipogenic properties of IGF-1 [31]. This suggests that an elevation of GHR signalling might enhance the utilization of yolk in faster growing larvae. Moreover, in the post-hatching stages, a higher sensitivity to GH through a higher receptor density might serve to increase appetite and foraging activity [49].

Growth compensation during early life-history stages is commonly observed in fishes [20,50,51]. A large size is thought to be highly beneficial during early life history as it reduces negative size-dependent mortality [21,52] and increases larval competitive abilities [53]. If being larger has clear benefits, then why do juveniles hatched from large eggs not grow faster? There is abundant evidence showing that substantial costs arise from fast growth, for example, various physiological costs and an enhanced predation risk because of increased activity [54]. Thus, the abovementioned benefits of a large size have to be traded off against the costs of fast growth, and it is conceivable that the benefits of fast growth only outweigh the costs for individuals that hatched from small eggs.

Expression levels of GHR were higher in the small-egg clutches already at an age when the larvae still have yolk reserves (day 8) and do not yet take up external food. It is hence unlikely that the larvae were able to predict future food abundance. It has been shown, however, that female S. pleurospilus produce smaller eggs when the expected food availability for the young is high [55]. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the upregulated GHR gene in larvae from smaller eggs might enable individuals hatched from small eggs to use the expected high food abundance more efficiently. Maternal diet appears to serve as a cue to predict the offspring rearing environment in a broad range of taxa, which usually triggers the production of smaller eggs [25,27,55,56], and/or of faster post-natal growth [57] when the offspring environment is predicted to be favourable. Possibly, mothers anticipating favourable conditions for their offspring can only afford to reduce egg size if a hormonal mechanism exists to result in an enhanced growth of young hatching from small eggs. We propose that a higher GHR expression is a promising candidate for such a mechanism. As we did not control for early maternal nutrition, we cannot be entirely sure if the egg sizes of our sampled clutches were environmentally induced or genetically determined. A long-term experiment tracking gene expression and growth for several generations under different environmental conditions would clarify whether maternal nutrition can indirectly influence offspring growth through differences in egg size.

GHR expression at 8 days after fertilization correlated positively with the average growth rates during the second month of life. Surprisingly, however, gene expression at 38 days after fertilization was not correlated with growth during this period, although an effect of egg size on GHR expression was still present. Furthermore, gene expression at day 8 and day 38 did not correlate (Spearman rank correlation, n = 10, rs = 0.12, p = 0.76). In general, maternal effects are thought to be most important in the earliest life stages, whereas with advancing age, other factors, such as the offspring's genotype and its current environment, are assumed to become more important [1,27,58,59]. Thus, the expression of GHR may start to be influenced by these other factors at day 38. More gene expression samples and growth measurements during the later life of the juveniles would be needed to see how long the effect of egg size on gene expression persists and if GHR expression is still able to affect growth during later life.

We propose three possible mechanisms for the enhanced GHR expression in young hatched from small eggs that are not mutually exclusive: (i) a maternal signal might have altered the activity state of embryonic genes. For example, maternal transcripts of GH, GHR, IGF-1 and IGF-2 have been detected in the unfertilized eggs and early embryos of various fish species [60–64], but their role is not well understood. It is unlikely, however, that a maternal signal consisting of GHR mRNA is responsible for faster growth in small-egg young because before hatching GHR transcripts were more abundant in large eggs. Possibly, a maternal signal might have been produced by genes not quantified in this study. For example, insulin and thyroid hormones are known to modulate GHR expression and function [65], and thyroid hormones are found in the unfertilized eggs of numerous fish species [66]. To test whether maternal signals can explain the differential GHR expression observed in our study, future studies should compare the quantities of maternally derived hormones and transcripts (e.g. by transcriptome analysis) that are present in eggs of different sizes before the onset of embryonic transcription. This requires the analysis of freshly spawned eggs within a few hours after spawning because, for example, in the cichlid fish O. niloticus, embryonic transcription has been estimated to start within 8 to 12 hours after fertilization [67]). These analyses could be initial steps in exploring which maternal mRNAs and hormones in the egg are potential candidates for transgenerational cues, which upregulate GHR expression in larvae. (ii) Alternatively, yolk quantity itself might have acted as a signal influencing juvenile growth. For example, sea urchins develop more slowly when hatched from experimentally yolk-reduced eggs [68]. To distinguish this possibility from the aforementioned mechanism, an experiment in which yolk is extracted from eggs [69] should be performed. A mechanism by which juveniles can control their growth gene expression independently of maternal cues might allow them to respond more flexibly to environmental conditions which require further adjustment of juvenile growth trajectories. For example, juveniles have been observed to grow slower when food is limited [35] and to grow faster when predation risk is higher [70]. However, a maternal cue might be preferable if mothers have more reliable information about the environment in which their young will grow [55,71]. (iii) Finally, the regulation of GHR gene expression might be an epigenetic effect, where chromosomal regions of offspring are structurally adapted to propagate an altered activity state of the gene, for example through DNA methylation or histone modification [72,73]. One should note that this mechanism could be a consequence of the first two mechanisms: changes in methylation marks might be induced by a maternal signal or by larval sampling of yolk quantity. Thus experiments in which the maternal signals have been identified (e.g. by transcriptome analysis) or in which the yolk amount was manipulated could be followed up by a study which quantifies the methylation of the promoter regions upstream of the GHR gene.

(a). Conclusions

The significance of egg properties and particularly egg size for life-history evolution has been studied extensively. However, the potential influence of egg size on offspring gene expression has been ignored so far. Here, we investigate gene expression patterns in relation to egg size. We detected an enhanced expression of GHR in S. pleuropilus juveniles originating from smaller eggs, and higher GHR mRNA levels were correlated to faster growth, such that juveniles hatching from small eggs fully compensated for their initial size disadvantage. Hitherto mechanisms of maternal effects have been studied mainly by quantifying deposited and circulating hormone levels in eggs and young. Our results demonstrate the importance of scrutinizing an additional level, the transcription of hormones and particularly their receptors, which ultimately determine tissue sensitivity to secreted hormones. Moreover, our study highlights the ecological and evolutionary significance of differential gene expression in relation to maternal effects.

Acknowledgements

The experiments carried out for this study conformed to the legal requirements of Switzerland (license number 57/07 and 21/08).

Many thanks to Barbara Gerber for help with fish maintenance and measurements. Many thanks also go out to Margaret Couvillon for correcting language mistakes. We are greatly indebted to Dik Heg, without whose help this work would not have been possible. FS would like to thank Francis Ratnieks for his hospitality during writing of this manuscript. This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 3100A0-111 796 to B.T.) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; grant P18 647-B16 to B.T.).

References

- 1.Bernardo J. 1996. The particular maternal effect of propagule size, especially egg size: patterns, models, quality of evidence and interpretations. Am. Zool. 36, 216–236 10.1093/icb/36.2.216 (doi:10.1093/icb/36.2.216) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mousseau T. A., Fox C. W. 1998. Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox C. W., Czesak M. E. 2000. Evolutionary ecology of progeny size in arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 45, 341–369 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.341 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.341) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall D. J., Uller T. 2007. When is a maternal effect adaptive? Oikos 116, 1957–1963 10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16203.x (doi:10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16203.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall D. J., Allen R. M., Crean A. J. 2008. The ecological and evolutionary importance of maternal effects in the sea. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 46, 203–250 10.1201/9781420065756.ch5 (doi:10.1201/9781420065756.ch5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eising C. M., Eikenaar C., Schwabl H., Groothuis T. G. G. 2001. Maternal androgens in black-headed gull (Larus ridibundus) eggs: consequences for chick development. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 839–846 10.1098/rspb.2001.1594 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1594) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uller T., Astheimer L., Olsson M. 2007. Consequences of maternal yolk testosterone for offspring development and survival: experimental test in a lizard. Funct. Ecol. 21, 544–551 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01264.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01264.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox C. W., Thakar M. S., Mousseau T. A. 1997. Egg size plasticity in a seed beetle: an adaptive maternal effect. Am. Nat. 149, 149–163 10.1086/285983 (doi:10.1086/285983) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einum S., Fleming I. A. 1999. Maternal effects of egg size in brown trout (Salmo trutta): norms of reaction to environmental quality. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 2095–2100 10.1098/rspb.1999.0893 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0893) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham E. J. A., Russell A. F. 2000. Egg investment is influenced by male attractiveness in the mallard. Nature 404, 74–77 10.1038/35003565 (doi:10.1038/35003565) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svensson E., Sinervo B. 2000. Experimental excursions on adaptive landscapes: density-dependent selection on egg size. Evolution 54, 1396–1403 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00571.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00571.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kudo S. 2001. Intraclutch egg-size variation in acanthosomatid bugs: adaptive allocation of maternal investment? Oikos 92, 208–214 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.920202.x (doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.920202.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormick M. I. 2003. Consumption of coral propagules after mass spawning enhances larval quality of damselfish through maternal effects. Oecologia 136, 37–45 10.1007/s00442-003-1247-y (doi:10.1007/s00442-003-1247-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown R. W., Taylor W. W. 1992. Effects of egg composition and prey density on the larval growth and survival of lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis Mitchill). J. Fish Biol. 40, 381–394 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1992.tb02585.x (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1992.tb02585.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamler E. 2005. Parent–egg–progeny relationships in teleost fishes: an energetic perspective. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 15, 399–421 10.1007/s11160-006-0002-y (doi:10.1007/s11160-006-0002-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith C. C., Fretwell S. D. 1974. The optimal balance between size and number of offspring. Am. Nat. 108, 499–506 10.1086/282929 (doi:10.1086/282929) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchings J. A. 1991. Fitness consequences of variation in egg size and food abundance in brook trout Salvelinus fontinalis. Evolution 45, 1162–1168 10.2307/2409723 (doi:10.2307/2409723) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segers F. H. I. D., Taborsky B. 2011. Egg size and food abundance interactively affect juvenile growth and behaviour. Funct. Ecol. 25, 166–167 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01790.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01790.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arendt J. D., Wilson D. S. 1997. Optimistic growth: competition and an ontogenetic niche-shift select for rapid growth in pumpkinseed sunfish (Lepomis gibbosus). Evolution 51, 1946–1954 10.2307/2411015 (doi:10.2307/2411015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertram D. F., Chambers R. C., Leggett W. C. 1993. Negative correlations between larval and juvenile growth rates in winter flounder: implications of compensatory growth for variation in size-at-age. Mar. Ecol-Prog. Ser. 96, 209–215 10.3354/meps096209 (doi:10.3354/meps096209) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sogard S. M. 1997. Size-selective mortality in the juvenile stage of teleost fishes: a review. Biol. Mar. Sci. 60, 1129–1157 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eldridge M. B., Whipple J. A., Bowers M. J. 1982. Bioenergetics and growth of striped bass, Morone saxatilis, embryos and larvae. Fish B-NOAA 80, 461–474 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semlitsch R. D., Gibbons J. W. 1990. Effects of egg size on success of larval salamanders in complex aquatic environments. Ecology 71, 1789–1795 10.2307/1937586 (doi:10.2307/1937586) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parichy D. M., Kaplan R. H. 1992. Maternal effects on offspring growth and development depend on environmental quality in the frog Bombina orientalis. Oecologia 91, 579–586 10.1007/BF00650334 (doi:10.1007/BF00650334) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotem K., Agrawal A. A., Kott L. 2003. Parental effects in Pieris rapae in response to variation in food quality: adaptive plasticity across generations? Ecol. Entomol. 28, 211–218 10.1046/j.1365-2311.2003.00507.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.2003.00507.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner E. C., Williams T. D. 2007. Experimental (antiestrogen mediated) reduction in egg size negatively affects offspring growth and survival. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 80, 293–305 10.1086/512586 (doi:10.1086/512586) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donelson J. M., Munday P. L., McCormick M. I. 2009. Parental effects on offspring life histories: when are they important? Biol. Lett. 5, 262–265 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0642 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0642) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heath D. D., Fox C. W., Heath J. W. 1999. Maternal effects on offspring size: variation through early development in Chinook salmon. Evolution 53, 1605–1611 10.2307/2640906 (doi:10.2307/2640906) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diz A. P., Dudley E., MacDonald B. W., Piña B., Kenchington E. L. R., Zouros E., Skibinski D. O. F. 2009. Genetic variation underlying protein expression in eggs of the marine mussel (Mytilus edulis). Mol. Cell Proteom. 8, 132–144 10.1074/mcp.M800237-MCP200 (doi:10.1074/mcp.M800237-MCP200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Roith D., Bondy C., Yakar S., Liu J. L., Butler A. 2001. The somatomedin hypothesis: 2001. Endocr. Rev. 22, 53–74 10.1210/er.22.1.53 (doi:10.1210/er.22.1.53) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinecke M., Björnsson B. T., Dickhoff W. W., McCormick S. D., Navarro I., Power D. M., Gutiérrez J. 2005. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factors in fish: where we are and where to go. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 142, 20–24 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.01.016 (doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.01.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders E. J., Harvey S. 2004. Growth hormone as an early embryonic growth and differentiation factor. Anat. Embryol. 209, 1–9 10.1007/s00429-004-0422-1 (doi:10.1007/s00429-004-0422-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gicquel C., Le Bouc Y. 2006. Hormonal regulation of fetal growth. Horm. Res. 65, 28–33 10.1159/000091503 (doi:10.1159/000091503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wood A. W., Duan C., Bern H. A. 2005. Insulin-like growth factor signalling in fish. Int. Rev. Cytol. 243, 215–285 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)43004-1 (doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(05)43004-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taborsky B. 2006. The influence of juvenile and adult environments on life-history trajectories. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 741–750 10.1098/rspb.2005.3347 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3347) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caelers A., Maclean N., Hwang G., Eppler E., Reinecke M. 2005. Expression of endogenous and exogenous growth hormone (GH) messenger (m) RNA in a GH-transgenic tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Transgenic Res. 14, 95–104 10.1007/s11248-004-5791-y (doi:10.1007/s11248-004-5791-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25, 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (doi:10.1006/meth.2001.1262) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caelers A., Berishvili G., Meli M. L., Eppler E., Reinecke M. 2004. Establishment of a real-time RT-PCR for the determination of absolute amounts of IGF-I and IGF-II gene expression in liver and extrahepatic sites of the tilapia. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 137, 196–204 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.03.006 (doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.03.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.R Development Core Team 2009. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faraway J. J. 2006. Extending the linear model with R 1st edn. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tse M. C., Vong Q. P., Cheng C. H., Chan K. M. 2002. PCR-cloning and gene expression studies in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) insulin-like growth factor-II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1575, 63–74 10.1016/S0167-4781(02)00244-0 (doi:10.1016/S0167-4781(02)00244-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peterson B. C., Waldbieser G. C., Bilodeau L. 2005. Effects of recombinant bovine somatotropin on growth and abundance of mRNA for IGF-I and IGF-II in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). J. Anim. Sci. 83, 816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponce M., Infante C., Funes V., Manchado M. 2008. Molecular characterization and gene expression analysis of insulin-like growth factors I and II in the redbanded seabream, Pagrus auriga: transcriptional regulation by growth hormone. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 150, 418–426 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.04.013 (doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.04.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aubin-Horth N., Renn S. C. P. 2009. Genomic reaction norms: using integrative biology to understand molecular mechanisms of phenotypic plasticity. Mol. Ecol. 18, 3763–3780 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04313.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04313.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gabillard J., Yao K., Vandeputte M., Gutierrez J., Le Bail P. 2006. Differential expression of two GH receptor mRNAs following temperature change in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Endocrinol. 190, 29–37 10.1677/joe.1.06695 (doi:10.1677/joe.1.06695) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Picha M. E., Turano M. J., Tipsmark C. K., Borski R. J. 2008. Regulation of endocrine and paracrine sources of IGFs and GH receptor during compensatory growth in hybrid striped bass (Morone chrysops × Morone saxatilis). J. Endocrinol. 199, 81–94 10.1677/JOE-07-0649 (doi:10.1677/JOE-07-0649) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan S. A., Cohen P. 2007. The somatomedin hypothesis 2007: 50 years later. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 4529–4535 10.1210/jc.2007-0526 (doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0526) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vijayakumar A., Novosyadlyy R., Wu Y., Yakar S., LeRoith D. 2009. Biological effects of growth hormone on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 20, 1–7 10.1016/j.ghir.2009.09.002 (doi:10.1016/j.ghir.2009.09.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Björnsson B. T. 2002. Growth hormone endocrinology of salmonids: regulatory mechanism and mode of action. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 27, 227–242 10.1023/B:FISH.0000032728.91152.10 (doi:10.1023/B:FISH.0000032728.91152.10) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chambers R. C., Leggett W. C., Brown J. A. 1988. Variation in and among early life-history traits of laboratory-reared winter flounder Pseudopleuronectes americanus. Mar. Ecol-Prog. Ser. 47, 1–15 10.3354/meps047001 (doi:10.3354/meps047001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gagliano M., McCormick M. I. 2007. Compensating in the wild: is flexible growth the key to early juvenile survival? Oikos 116, 111–120 10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.15418.x (doi:10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.15418.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gislason H., Daan N., Rice J. C., Pope J. G. 2010. Size, growth, temperature and the natural mortality of marine fish. Fish Fish. 11, 149–158 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00350.x (doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00350.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marshall D. J., Cook C. N., Emlet R. B. 2006. Offspring size effects mediate competitive interactions in a colonial marine invertebrate. Ecology 87, 214–225 10.1890/05-0350 (doi:10.1890/05-0350) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metcalfe N. B., Monaghan P. 2001. Compensation for a bad start: grow now, pay later? Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 254–260 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02124-3 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02124-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taborsky B. 2006. Mothers determine offspring size in response to own juvenile growth conditions. Biol. Lett. 2, 225–228 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0422 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0422) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vijendravarma R. K., Narasimha S., Kawecki T. J. 2010. Effects of parental diet on egg size and offspring traits in Drosophila. Biol. Lett. 6, 238–241 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0754 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0754) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Sman J., Phillips N., Pfister C. A. 2009. Relative effects of maternal and juvenile food availability for a marine snail. Ecology 90, 3119–3125 10.1890/08-2009.1 (doi:10.1890/08-2009.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Einum S., Fleming I. A. 2000. Highly fecund mothers sacrifice offspring survival to maximize fitness. Nature 405, 565–567 10.1038/35014600 (doi:10.1038/35014600) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lindholm A. K., Hunt J., Brooks R. 2006. Where do all the maternal effects go? Variation in offspring body size through ontogeny in the live-bearing fish Poecilia parae. Biol. Lett. 2, 586–589 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0546 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0546) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang B., Greene M., Chen T. T. 1999. Early embryonic expression of the growth hormone family protein genes in the developing rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Mol. Reprod. Dev. 53, 127–134 (doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199906)53:2<127::AID-MRD1>3.0.CO;2-H) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ayson F. G., de Jesus E. G., Moriyama S., Hyodo S., Funkenstein B., Gertlerm A., Kawauchi H. 2002. Differential expression of insulin-like growth factor I and II mRNAs during embryogenesis and early larval development in rabbitfish, Siganus guttatus. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 126, 165–174 10.1006/gcen.2002.7788 (doi:10.1006/gcen.2002.7788) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maures T., Chan S. J., Xu B., Sun H., Ding J., Duan C. 2002. Structural, biochemical and expression analysis of two distinct insulin-like growth factor I receptors and their ligands in zebrafish. Endocrinology 143, 1858–1871 10.1210/en.143.5.1858 (doi:10.1210/en.143.5.1858) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aegerter S., Jalabert B., Bobe J. 2004. Messenger RNA stockpile of cyclin B, insulin-like growth factor I, insulin-like growth factor II, insulin-like growth factor receptor Ib, and p53 in the rainbow trout oocyte in relation with developmental competence. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 67, 127–135 10.1002/mrd.10384 (doi:10.1002/mrd.10384) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ozaki Y., Fukada H., Tanaka H., Kagawa H., Ohta H., Adachi S., Hara A., Yamauchi K. 2006. Expression of growth hormone family and growth hormone receptor in the Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica). Comp. Biochem. Phys. B 145, 27–34 10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.05.009 (doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.05.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Birzniece V., Sata A., Ho K. K. Y. 2009. Growth hormone receptor modulators. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 10, 145–156 10.1007/s11154-008-9089-x (doi:10.1007/s11154-008-9089-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tagawa M., Tanaka M., Matsumoto S., Hirano T. 1990. Thyroid hormones in eggs of various freshwater, marine and diadromous teleosts and their changes during egg development. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 8, 515–520 10.1007/BF00003409 (doi:10.1007/BF00003409) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morrison C. M., Miyake T., Wright J. R. 2001. Histological study of the development of the embryo and early larva of Oreochromis niloticus (Pisces: Cichlidae). J. Morphol. 247, 172–195 (doi:10.1002/1097-4687(200102)247:2<172::AID-JMOR1011>3.0.CO;2-H) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sinervo B., McEdward L. R. 1988. Developmental consequences of an evolutionary change in egg size: an experimental test. Evolution 42, 885–899 10.2307/2408906 (doi:10.2307/2408906) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morley S. A., Batty R. S., Geffen A. J., Tytler P. 1999. Egg size manipulation: a technique for investigating maternal effects on the hatching characteristics of herring. J. Fish Biol. 55, 233–238 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb01059.x (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb01059.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bell A. M., Dingemanse N. J., Hankison S. J., Langenhof M. B. W., Rollins K. 2011. Early exposure to nonlethal predation risk increases somatic growth and decreases size at adulthood in threespined sticklebacks. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 943–953 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02247.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02247.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kotrschal A., Heckel G., Bonfils D., Taborsky B. 2011. Life-stage specific environments in a cichlid fish: implications for inducible maternal effects. Evol. Ecol. (doi:10.1007/s10682-011-9495-5) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bossdorf O., Richards C. L., Pigliucci M. 2008. Epigenetics for ecologists. Ecol. Lett. 11, 106–115 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01130.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01130.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ho D. H., Burggren W. W. 2009. Epigenetics and transgenerational transfer: a physiological perspective. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 3–16 10.1242/jeb.019752 (doi:10.1242/jeb.019752) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]