Abstract

The aim of the present study was to provide a method for evaluating bone toxicity induced by drugs in various bones in aged rats. Male Crl:CD (SD) rats at 46 weeks of age were administered 15 mg/m2 body surface area of doxorubicin, which effects the growth plate in weanling rats, weekly for 9 weeks by intravenous injection, and the femur, sternum, humerus and tibia were examined histopathologically. In the doxorubicin-treated group, thinning of the growth plate was remarkably observed in the proximal tibia and humerus; however, these changes were not observed in other regions. In addition, the osteoclast number per bone perimeter in the proximal tibia was significantly higher than others in control aged rat. Thus, recognizing the various histological reactions related to the time of epiphyseal closure is important for evaluating bone toxicity in aged rats.

Keywords: bone toxicity, rat, growth plate, epiphyseal closure, doxorubicin

Introduction

The skeletal system is composed of a variety of specialized forms of supporting or connective tissue, and bone provides a rigid protective and supportive framework for most of the soft tissues of the body1. Naturally, bone also acts as a calcium reservoir and is important in calcium homeostasis; additionally, bone is a metabolically active tissue, and its formation, modeling and remodeling are influenced by many factors or conditions, especially hormonal and dietary factors or conditions1,2. The above facts mean that the skeletal system has one of the most important functions of all the organs, and it is important to identify changes in the skeletal system in toxicological studies. On the other hand, a large number of bones have multiple functions in animal bodies and differ from one another to some degree in terms of development and growth. For instance, the fetal development of bone occurs in two ways, intramembranous ossification and endochondral ossification1. In addition, the time of fusion of the secondary ossification centers in the long bones is known to vary in men, rats and other animals3, and the maturation process differs in various bones at the same age.

The pathologic and physiologic mechanisms of toxic bone disease are often not well understood4. The number of agents reported to have a direct toxic effect on bone or cartilage has been somewhat limited, and we may have not yet learned how to evaluate the early primary toxic effects of drugs, chemicals or other environmental agents on hard tissues4. Some agents that cause skeletal pathologic changes are known, such as corticosteroids, causing aseptic necrosis of the femoral head4,5, and bisphosphonate, causing inhibition of osteoclast function4,6. Doxorubicin (DOX), a cancer chemotherapeutic agent, is well known to induce major toxicities such as cardiotoxicity7,8 and glomerulonephropathy7,9, in addition to inhibiting the proliferation of growth plate chondrocytes, leading to growth plate thinning and longitudinal growth retardation when weanling rats (around 4 weeks old) are treated with DOX10.

However, most exogenous chemicals are known to exert their effects on the skeleton via secondary mechanisms, usually mediated by alterations in blood flow within the skeleton, and substances inducing secondary skeletal changes are usually either hormones, vitamins or minerals or affect the metabolism of skeletal-regulating agents4. Age is also known to affect the responsiveness of the skeletal system, and it is well recognized that fracture healing is less vigorous in older individuals than in young individuals4. Consequently, age-related changes and treatment-induced changes are not uniform throughout the skeleton11.

Evaluating bone toxicity can be problematic for several reasons. One issue is the age of the animals at the time of evaluation. Practically, the femur and sternum are often included in standard tissue lists of bone toxicity when bone is evaluated in repeat-dose toxicity studies morphologically12–15, and these bones are typically used in animals of all ages and in both short-term and long-term studies, though the time of epiphyseal closure is known to differ in some regions3,16. For instance, in the distal femur, proximal humerus and tibia, the time of fusion of the secondary ossification centers varies, as shown using X-ray radiography in rats around 50 weeks of age3. In this situation, whether the evaluation of bone toxicity can be effectively performed in a practical manner remains debatable.

Bone toxicity must be measured accurately using animals of an appropriate age; for this purpose, the bone regions most suitable for evaluating bone toxicity must be determined according to the age of the animal model. Therefore, the present study was performed to investigate histopathologically possible differences in the effects on bones in different regions and with different time of epiphyseal closure in aged rats (around 50 weeks old) dosed with DOX.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

Eight 46-week-old male Crl:CD (SD) rats weighing 649–910 g and four 8-week-old male Crl:CD (SD) rats weighing 293–333 g purchased from Charles River Japan (Kanagawa, Japan) were maintained under the following conditions: temperature of 20–26 °C, relative humidity of 30–70%, a 12-h light/dark cycle and a ventilation frequency of 5–40 air exchanges/h. Each rat had free access to a laboratory pellet diet for rats (MF, Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and tap water. The maintenance and experimental protocols conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Study design

Eight rats at 46 weeks of age were divided into two groups of four: a control group and a DOX-treated group. DOX (Doxorubicin; Kyowa Hakko Kogyo, Tokyo, Japan) was administered 5 times every second week by injection into the tail vein at doses of 15 and 0 (control) mg/m2 body surface area; the former dose is known to affect the growth plate of rats at an age of 4–5 weeks10. The body surface area (BSA [m2]) was calculated for each rat using the following formula: BSA = k•w2/3/104, with k = constant [m2/gr2/3 ], chosen to be 9·5, and w = weight [grams]. The animals were euthanized at 55 weeks of age at the end of the study period one week after the last administration of DOX, except for one of the DOX-treated animals that died at 53 weeks of age because of exhaustion and wasting. To compare the bones of aged rats with young rats and detect of cellular proliferation, four rats at 8 weeks of age that were not treated with DOX were euthanized and used as positive control specimens.

Histopathologic methods

The growth plates, articular cartilage and cortical bone of the distal femur, sternum (4th sternebra), proximal humerus and tibia were histopathologically examined in all the animals. Samples were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin, decalcified with Plank-Rychlo’s solution, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4–5 µm. The specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and were histologically examined using a light microscope similar to the routine histopathological evaluations performed in toxicity studies. For qualitative analysis of cellular proliferation, the specimens of all regions were assessed by immunohistochemical staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen17 ([PCNA], PC10, Dako, Japan) using the LSAB method (Dako LSAB2 kit; Dako, Japan) and the same regional specimens in young rats (8 weeks old) as a positive control for PCNA, as mentioned above.

Histomorphometric methods

HE stained sections were viewed under a light microscope at a magnification of ×40, and measurements were performed using the image analysis software Image-pro PLUS (Verion 6.3, Media Cybernetics, Nippon Roper Co., Ltd.). To measure the growth plate height, three areas per section were analyzed. Standard histomorphometry nomenclature, symbols and calculations were used18. Ten areas per section were analyzed for osteoblast and osteoclast number per bone perimeter (Ob.N/B.Pm; Oc.N/B.Pm). Though an exact discrimination of these cells is difficult using HE staining, these cells were distinguished as follows. Osteoclasts were regarded as large multinucleated, resorbing cells, whereas osteoblasts were regarded as mononuclear and cuboidal or columnar bone lining cells with abundant basophilic cytoplasm1,2,18.

Statistical analyses

The mean value and standard error (S.E.) of the numerical data obtained from the histomorphometric analysis were calculated for each group. To analyze the differences in several regions of bone in the control group, the statistical significance between the femur, which is often included in standard tissue lists for bone toxicity, and each other bone (sternum, tibia, humerus) was analyzed using a multiple comparison test. For comparison of 3 or more bones, the homogeneity of variance was analyzed using the Bartlett test (p < 0.05) followed by a one-way analysis of variance when the variance was homogeneous. If a significant difference was found among the groups, the Dunnett test (parametric) was performed to test the differences between the mean values for the femur and each of the other bones. When the variance was heterogeneous, the Kruskal-Wallis H-test (p < 0.05) was applied; if a significant difference was found among the groups, the Dunnett test (nonparametric) was performed to test the differences between the mean values for the femur and each of the other bones. To analyze the bones between the control and DOX-treated animals, the statistical significance of differences between the control and DOX-treated group was analyzed for equality of variance using the F-test (p < 0.05), and then the Student’s t-test or Aspin-Welch t-test was conducted depending on whether the variances were equal or not. The SAS preclinical package (version 5.0, SAS Institute Inc.) was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Growth plate morphology of aged rats in the control group

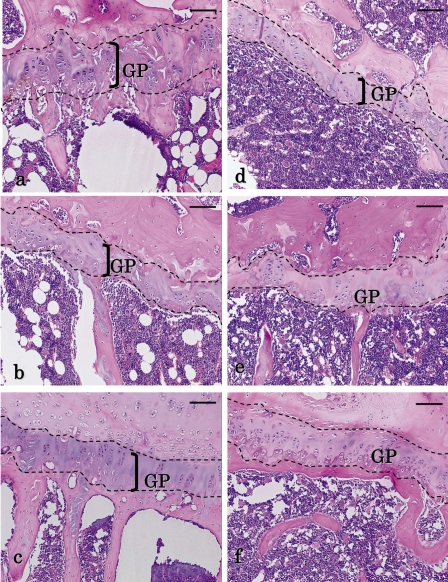

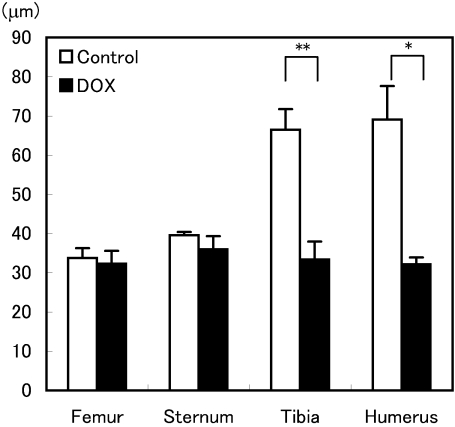

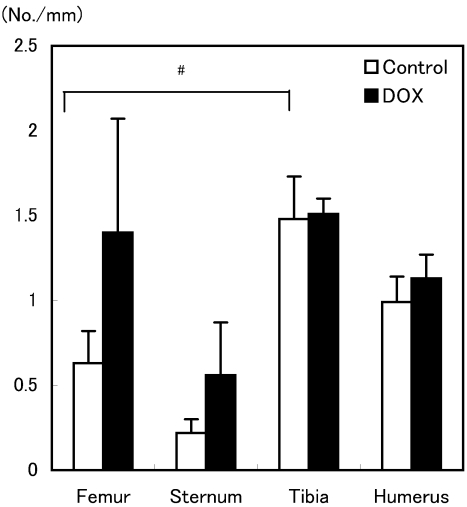

In the control rats, the histomorphological results for the growth plates were quite distinct for each region. Regarding the heights of the growth plate in the HE stained section, the proximal humerus and tibia were thicker and arranged in regularly characteristic longitudinal columns compared with the distal femur and sternum (Fig 1). When compared with the femur, a standard tissue commonly used in toxicological studies, and other bones using a histomorphometric analysis, no significant changes were observed, although the growth plate height tended to be thicker in the tibia and humerus (Fig 2). According to Ob.N/B.Pm and Oc.N/B.Pm, the Oc.N/B.Pm of the tibia was significantly larger than that in the femur and other bones in the control group (Figs 3 and 4). To determine the incidence of chondrocyte proliferation, sections were stained for PCNA, a marker for proliferating cells17; the heights of the growth plate differed widely among the regions, but PCNA-positive cells were not obvious in all regions. In a young animal as a positive control for PCNA, the growth plates had plenty of height, and a high incidence of chondrocytes in the proliferative zone was observed in all the regions (Fig 5).

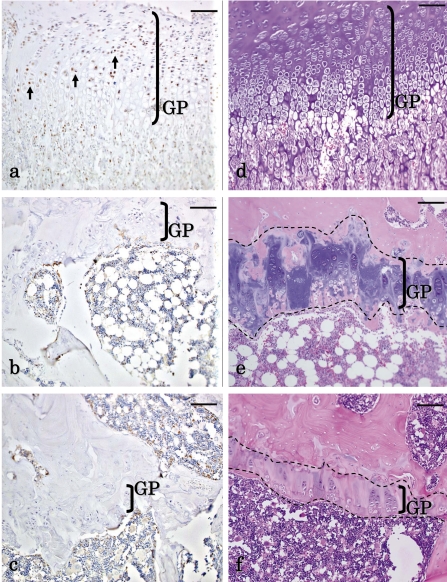

Fig. 1.

Histopathological changes of the growth plate in aged rats. The growth plates (GP) of the (a) humerus, (b) femur and (c) sternum are shown for the control group. The GP of the (d) humerus, (e) femur and (f) sternum are shown for the DOX-treated group. (a–c) The GP in the humerus is thicker than those of the femur and sternum in the control. (d) In comparison of the humerus between the control and DOX-treated animals, the GP in the DOX-treated group was obviously thinner than that in the control. In addition, the zone of hypertrophy and calcification and the zone of cartilage degeneration decreased or disappeared. (e) Remarkable thinning of the GP was not observed in the femur of the DOX-treated group, and the zone of hypertrophy and calcification and the zone of cartilage degeneration almost disappeared in both groups, though the zone of cartilage degeneration partially remained in the femur. (f) The thinning of the GP was not remarkably observed in the sternum of the DOX-treated group, and the zone of hypertrophy and calcification and the zone of cartilage degeneration practically disappeared in both groups. Moreover, the osteogenic zone was thick in both groups. HE staining. Scale bars indicate 100 µm.

Fig. 2.

Growth plate heights of the distal femur, sternum, proximal tibia and humerus after treatment with DOX in aged rats. The growth plates of the tibia and humerus in the DOX-treated group became significantly thinner than those in the control group. Values are means ± SEM (n=3–4 animals/group). * p<0.05 for comparisons of the humerus between the DOX-treated group and control group. ** p<0.01 for the comparisons of the tibia between the DOX treated group and control group.

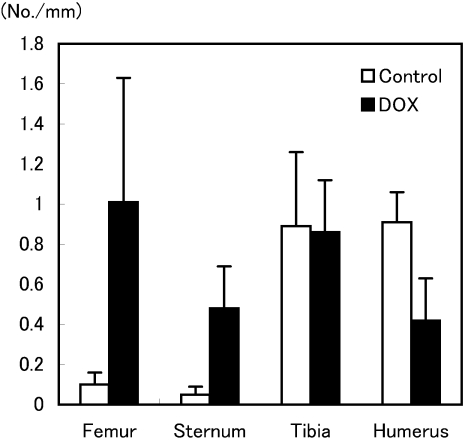

Fig. 3.

Ob.N/B.Pm of the distal femur, sternum, proximal tibia and humerus after treatment with DOX in aged rats. The Ob.N/B. Pm of the femur and sternum in the DOX-treated group tended to be higher than those in the control group. Values are means ± SEM (n=3–4 animals/group).

Fig. 4.

Oc.N/B.Pm of the distal femur, sternum, proximal tibia and humerus after treatment with DOX in aged rats. The Oc.N/B. Pm of the tibia in the control group was significantly higher than that of the femur in the control group. Values are means ± SEM (n=3–4 animals/group). # p<0.05 for comparisons between the femur and tibia in the control group.

Fig. 5.

Changes of histopathological and immunohistochemical staining in chondrocytes of the proliferative zone in the growth plate of the tibia. (a) The growth plates (GP) of the young control animals were positive for PCNA expression in the nuclei of the chondrocytes. (b) The GP of the aged control animals showed no obvious staining for PCNA. (c) The GP of the aged DOX-treated animals showed no obvious staining for PCNA. (d) The growth plates of the young animals were relatively thick (HE staining). (e) The GP of the aged control animals were thinner than those of the young animals, particularly in the zone of hypertrophy and calcification and the zone of cartilage degeneration (HE staining). (f) The GP of the DOX-treated animals were much thinner than those of the aged control animals, and in approximately half of the animals, the zone of hypertrophy and calcification and the zone of cartilage degeneration had decreased or disappeared (HE staining). Scale bars indicate 100 µm.

Growth plate morphology of the tibia and humerus in DOX-treated rats

DOX-treated rats exhibited some histopathological changes compared with the control group; however, these changes differed in each region. In the proximal tibia, a remarkable thinning of the growth plate was observed in the majority of DOX-treated animals; in particular, the zone of hypertrophy and calcification and the zone of cartilage degeneration decreased or disappeared in the humerus and tibia in the DOX-treated group, and the growth plate of the DOX-treated animals was thinner than that in the control (Fig 5). These histomorphometric changes were significant (Fig 2). No significant changes in Ob.N/B.Pm and Oc.N/B. Pm were observed (Figs 3 and 4). PCNA-positive cells were not obvious in all regions (Fig 5). In the proximal humerus, the results were the same as those for the proximal tibia; however, in the proximal tibia, the growth plate height was significantly thicker than that in the proximal humerus.

Growth plate morphology of the femur and sternum in DOX-treated rats

In the distal femur and sternum, thinning of the growth plate was not remarkably observed.

In the femur and sternum, a few chondrocytes were present in the growth plate, and the heights of the growth plates were similar to those in the DOX-treated group (Fig 1). The zone of hypertrophy and calcification and the zone of cartilage degeneration almost disappeared in both the femur and the sternum, and remarkable thinning of the growth plate was not observed. In addition, the osteogenic zone was relatively thick in the sternum in both groups and not arranged in characteristic longitudinal columns composed of small chondrocytes compared with the other bones. No significant changes in the histomorphometrical analysis were observed (Fig 2). In the femur, the zone of cartilage degeneration of the metaphysis tended to disappear but partially remained. Regarding the Ob.N/B.Pm and Oc.N/B.Pm, no significant changes were observed, but higher values tended to be observed in the DOX-treated group (Figs 3 and 4).

Concerning articular cartilage, cortical bone and the cellular morphology of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, no remarkable findings were observed in any of the regions. In the growth plates of the aged control and DOX-treated animals, the height of the growth plate differed widely among the regions, as mentioned above, though PCNA-positive cells were not obvious in all the regions.

Discussion

Practically, when bone is evaluated morphologically in repeat-dose toxicity studies in rats, the femur and sternum are often included in standard tissue lists for the evaluation of bone toxicity, as recommended in the guidelines of the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)12–15. These methods are suitable for evaluation of bones in growing animals in toxicological studies. However, drug safety must also be evaluated in toxicity studies at other growth stages, such as in weanling animals for evaluation of infant, and aged animals for evaluation of aging people. Thus, it is important to evaluate drug safety in consideration of the action and indications of the drugs. The aim of this study was to examine the evaluation of bone toxicity in consideration of the age of the animals.

First of all, the morphological differences of the aged rats in the control group were examined. In the control aged rats, the histomorphological results for growth plates were quite distinct in each region. Regarding the height of the growth plate in HE-stained sections, the growth plates of the proximal humerus and tibia were thicker and arranged regularly in characteristic longitudinal columns compared with the distal femur and sternum. In comparison with the femur, a standard tissue commonly used in histomorphometric analyses for toxicological studies, no significant changes were observed, although the growth plate height tended to be thicker in the tibia and humerus. Moreover, the Oc.N/B. Pm in the tibia was increased significantly compared with that in the femur in the control group.

On the other hand, a large number of bones have multiple functions in animal bodies and differ from one another to some degree in terms of development and growth. For instance, fetal development of bone occurs in two ways1. The bones of the vault of the skull, the maxilla and most of the mandible are formed by direct replacement of mesenchyme with bone1. This process is called intramembranous ossification and results in so-called membrane bones1. In contrast, the long bones, vertebrae, pelvis and bones of the skull are preceded by the formation of a continuously growing cartilage model that is progressively replaced by bone1. This process is called endochondral ossification and enables the formation of bone that is capable of sustaining functional stresses, resulting in the formation of so-called cartilage bones1. During endochondral ossification, replacement with bone begins at the primary ossification center in the diaphysis, with regressive changes and bone formation also occurring from a secondary ossification center in the epiphyses1. At physical maturity, the process of endochondral ossification ceases, and fusion of the secondary ossification centers occurs1. In addition, the time of fusion of the secondary ossification centers in the long bones is known to vary in men, rats and other animals3, and the maturation process differs in various bones at the same age. In other words, the maturation processes of the respective secondary ossification centers vary with the bones, which might be classified into the following three types: (1) acute ossification type, which requires a relatively short period from the time of appearance until fusion; (2) delayed ossification type, which requires a relatively long period for completion of fusion; and (3) incomplete ossification type3. In the present study, the distal femur appeared to be an acute ossification type, the proximal humerus appeared to be a delayed ossification type and the proximal tibia appeared to be an incomplete ossification type3. In detail, the time of fusion of the secondary ossification centers was 15–17 weeks in the distal femur, 52 weeks in the proximal humerus and 104 weeks or longer in the proximal tibia3. The incomplete ossification type is thought to be characteristic of certain rodents such as rats and mice, and the time of 17 to 21 weeks would be considered the endpoint of the maturation process in the rat3. However, extensive remodeling and bone formation occur within cellular regions of the growth plate, and direct bone formation by former growth plate chondrocytes are in progress during this period17. These changes were reflected in the aged control rats in that the heights of the growth plates in the proximal humerus and tibia were thicker and arranged regularly in characteristic longitudinal columns compared with those in the distal femur and sternum.

Particularly, a significantly large Oc.N/B.Pm was observed in the tibia; consequently, the proximal tibia was thought to be an incomplete ossification type. These data suggest that the growth plate of the tibia would reflect only slight effects in toxicology studies performed in aged rats. Concerning the sternum, the time of fusion of the secondary ossification centers has not been previously reported, although thickening of the trabecular bone has been observed in rats at 180 days old19, and the cartilage cells in the proliferating zone were confined to fewer layers than in the sternum of 8 week-old rats. Similar results were also observed in the present study.

When the control and DOX-treated groups were compared, pathological changes in the heart, appearing as vacuolization of the myocytes8, and kidney, appearing as vacuolization of the glomerular basement membrane9, were confirmed, indicating that DOX was administered at a toxic dose (data not shown). Nevertheless, observation of the femur and sternum, two standard tissues often used in toxicology studies, did not show obvious toxic effects of DOX.

It is also well known that thinning of the growth plate is observed in growing animals dosed with DOX, such as weanling rats10 and young rabbits (around 6–8 weeks old)20. In the present study, thinning of the growth plate was also observed in aged rats, not in the distal femur and sternum, but in the proximal humerus and tibia. In this study, the rats were treated from 46 weeks of age, which is when the proximal humerus (a delayed ossification type bone) had not yet undergone fusion of the secondary ossification centers or epiphyseal union; thinning of the growth plate was observed in these bones, which is similar to the observations in growing animals. This phenomenon was also observed in the proximal tibia, an incomplete ossification-type bone. As for the distal femur, the time of fusion of the secondary ossification centers (epiphyseal union) had already occurred, and the growth plate had become thinner than those of the proximal humerus and tibia, so no obvious thinning of the growth plate was observed. In the control animals in this study, the growth plate of the sternum was thinner than those of the proximal humerus and tibia but similar to that of distal femur, which is an acute ossification type bone; consequently, no obvious thinning of the growth plate was observed in the DOX-treated rats.

DOX is known to inhibit the proliferation of growth plate chondrocytes10. In addition, the mechanism of this change has been considered to be as follows. DOX is a well-known anthracycline and DNA intercalator, which is the main factor of epiphyseal growth21, and the inhibitory action of DOX on DNA-directed RNA synthesis and protein synthesis tends to retard the production of cartilage matrix in growing animals20. DOX also reportedly binds to the crystalline surfaces of bone in vitro; therefore, DOX affects adversely both the organic and inorganic fractions of bone20. Though PCNA-positive cells were not obvious in all the growth plates observed in the control and DOX-treated aged rats in the present study, the inhibitory action of DOX on DNA-directed RNA synthesis did not cause the thinning of the growth plate in the aged animals. It seems that the thinning of the growth plate in aged animals would be caused by DOX binding to the crystalline surfaces of bone.

The growth plate morphology of the aged rat differs from that of the young rat. For instance, despite the continued presence of growth plate in the aged rat, longitudinal growth no longer occurs17. In the aged rat, it is similar to endochondral ossification in that resorption of cartilage matrix is followed by bone deposition onto the walls of the resorbed cavities. Though the location of this ossification is different, it is found within the core of the growth plate cartilage in the aged rat, not within the vascular/marrow space as would be the case in a younger rat17. Moreover, in the growth plate of the aged rat, the proliferation of chondrocytes is inhibited, some chondrocytes become bone-forming cells and direct bone formation occurs in the former growth plate chondrocytes17. Considering such a particular process of the growth plate in the aged rat, DOX would bind to the crystalline surfaces of bone that formed directly in the growth plate and prevent direct bone formation in the growth plate and then cause thinning of the growth plate in aged animals.

According to the Ob.N/B.Pm and Oc.N/B.Pm, no significant changes were observed between the control and DOX-treated groups, though higher values tended to be observed in the femur and sternum of the DOX-treated group. As stated above, the mechanisms of DOX affecting bone are the inhibitory action of DOX on DNA-directed RNA synthesis and binding of DOX to the crystalline surfaces of bone. Moreover, numerous reports have discussed how the number and activities of osteoclasts and osteoblasts change in DOX-treated animals, and the effects of osteoclasts and osteoblasts varied widely among the regions examined in the present study as well as in previous reports7,20,22. These reports suggest that the changes of Ob.N/B.Pm and Oc.N/B. Pm would be indirect changes related to a primary change in the bone, which is thinning of the growth plate, or kidney failure. In this study, the increases in the Ob.N/B.Pm and Oc.N/B.Pm of the femur and sternum were thought to be secondary changes, and a direct change, caused by DOX, thinning of the growth plate, was observed in the tibia and humerus. These data suggest that the growth plates of the tibia and humerus are more suitable for evaluation of toxicity studies in aged rats than the femur and sternum. Moreover, further study is required using chemicals that have other toxicological mechanisms, that affect osteoclasts, osteoblasts and so forth.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that some differences in bone regions exist in aged rats treated with DOX, depending on the time of epiphyseal closure. Thus, the area of observation must be considered when evaluating bone toxicity in aged rats, since the bone maturation process varies according to bone type in rats. In addition, this opinion should be studied further using chemicals that have other toxicological mechanisms.

References

- 1.Young B, Heath JW. Wheather’s Functional Histology a Text and Colour Atlas, 4th ed. Churchill livingstone, Edinburgh. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leininger JR, Riley MG. Bones, joints, and synovia. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat. GA Boorman, SL Eustis, MR Elwell, C Montgomery Jr., and WF Mackenzie (eds). Academic press, San diego. 209–226. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda S, Matsuoka O. Maturation process of secondary ossification centers in the rat and assessment of bone age. Exp Anim. 28: 1–9 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodard JC, Jee WS. Skeletal system. In: Fundamentals of Toxicologic Pathology. WM Haschek and CG Rousseaux (eds). Academic Press, San Diego. 275–308. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boss JH, Misselevich I. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head of laboratory animals: the lessons learned from a comparative study of osteonecrosis in man and experimental animals. Vet Pathol. 40: 345–354 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers MJ, Gordon S, Benford HL, Coxon FP, Luckman SP, Monkkonen J, Frith JC. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Cancer. 88: 2961–2978 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comereski CR, Peden WM, Davidson TJ, Warner GL, Hirth RS, Frantz JD. BR96-doxorubicin conjugate (BMS182248) versus doxorubicin: a comparative toxicity assessment in rats. Toxicol Pathol. 22: 473–488 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mettler FP, Young DM, Ward JM. Adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity (Cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure) in rats. Cancer Res. 37: 2705–2713 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertani T, Poggi A, Pozzoni R, Delaini F, Sacchi G, Thoua Y, Mecca G, Remuzzi G, Donati MB. Adriamycin-induced nephrotic syndrome in rats. Lab Invest. 46: 16–23 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Leeuwen BL, Hartel RM, Jansen HW, Kamps WA, Hoekstra HJ. The effect of chemotherapy on the morphology of the growth plate and metaphysis of the growing skeleton. EJSO. 29: 49–58 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith R, Kiebzak GM. Effects of aging and exercise on the skeleton. In: Pathology of Aging Rat Volume 2. U Mohr, DL Dungworth, and CC Capen (eds). International Life Science Institute, Washington, D. C. 549–564. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morawietz G, Fehlert CR, Kittel B, Bube A, Keane K, Halm S, Heuser A, Hellmann J. Revised guides for organ sampling and trimming in rats and mice— part 3. Exp Toxic Pathol. 55: 433–449 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redbook 2000 chapter IV. B. 1: General guidelines for designing and conducting toxicity studies. 2009, from U.S. Food and drug administration, Center for food safety and applied nutrition website: http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/FoodIngredientsandPackaging/Redbook/ ucm078315.htm

- 14.Study Group for Nonclinical Studies of Drugs Japanese Guidelines for Nonclinical Studies of Drugs Manual 2002. Yakuji Nippo Ltd., Tokyo. 2002. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bregman CL, Adler RR, Morton DG, Regan KS, Yano BL. Recommended tissue list for histopathologic examination in repeat-dose toxicity and carcinogenicity studies: a proposal of the society of toxicologic pathology (STP). Toxicol Pathol. 31: 252–253 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson AB. The age order of epiphyseal union in the long bones of the albino rat. Anat Rec. 31: 1–17 1925 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roach HI, Mehta G, Oreffo RO, Clarke NM, Cooper C. Temporal analysis of rat growth plates: cessation of growth with age despite presence of a physis. J Histochem Cytochem. 51: 373–383 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. JBMR. 2: 595–610 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jasty V, Bare JJ, Jamison JR, Porter MC, Kowalski RL, Clemens GR, Jackson GE, Jr, Hartnagel RE., JrSpontaneous lesions in the sternums of growing rats. Lab Anim Sci. 36: 48–51 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young DM, Fioravanti JL, Olson HM, Prieur DJ. Chemical and morphologic alterations of rabbit bone induced by adriamycin. Calcif Tiss Res. 18: 47–63 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Leeuwen BL, Kamps WA, Jansen HW, Hoekstra HJ. The effect of chemotherapy on the growing skeleton. Cancer Treat Rev. 26: 363–376 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedlaender GE, Tross RB, Doganis AC, Kirkwood JM, Baron R. Effects of chemotherapeutic agents on bone. I. Short-term methotrexate and doxorubicin (adriamycin) treatment in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg. 66: 602–607 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]