Abstract

We investigated a case of spontaneous malignant T-cell lymphoma observed in a 19-week-old male Crl:CD (SD) rat. The rat showed paralysis beginning 1 week before euthanasia. Hematological examination revealed marked lymphocytosis without distinct atypia. Macroscopically, hepatosplenomegaly and partial atrophy of the thoracic spinal cord were observed. Microscopically, neoplastic cells infiltrated into the liver, splenic red pulp, bone marrow and epidural space of the thoracic spinal cord, while no neoplastic cells were observed in the thymus and lymph nodes. Moreover, the spinal cord showed focal degeneration due to compression by marked infiltration of neoplastic cells in the subdural space. The neoplastic cells were generally small-sized round cells that had a round nucleus with/without a single nucleolus and scanty cytoplasm. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD3 and CD8 and negative for CD79α. Judging from these results, the present tumor in this young adult rat was diagnosed as malignant T-cell lymphoma.

Keywords: T-cell lymphoma, young-adult, SD rat, paralysis, spontaneous

Introduction

With the exception of large granular lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma in Fischer 344 rats 1 and lymphoblastic lymphoma in inbred SD/Cub rats, 2 malignant lymphoma is a tumor of rats with a low incidence. Spontaneous malignant T-cell lymphoma in young adult rats has been reported in the Long Evans 3 and Wistar 4 strains, and early occurrence of malignant lymphoma has been reported in Sprague-Dawley rats 5 . In the latter case, however, no histopathological descriptions have been presented. In the present report, we describe a case of spontaneous malignant T-cell lymphoma accompanied by paralytic gait in a young adult Crl:CD (SD) rat.

The animal was a male Sprague-Dawley rat purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan) at 5 weeks of age and used in one treatment group for a toxicity study after a 1-week quarantine period. The animals that study were housed individually in a wire mesh cage under controlled conditions (temperature of 23 ± 3°C, relative humidity of 50 ± 20% and 12-h light/dark cycle) and fed CRF-1 diet (Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and tap water ad libitum. They were treated in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Bozo Research Center Inc. The present case was euthanized under ether anesthesia at 19 weeks of age due to moribund condition. At necropsy, a blood sample was collected from the inferior vena cava. Hematological examination was performed with a Coulter Counter T890 (Beckman-Coulter Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and blood smear specimens were prepared using May-Giemsa staining for microscopic examination. After complete necropsy, all tissues including the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues (spleen, mesenteric lymph node, sternal bone marrow and thymus), thoracic spinal cord and liver were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin (pH7.2), embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological examination. For immunohistochemical examination, selected serial sections from the liver, spleen and sternal bone marrow were subjected to the dextran polymer method using an Envision kit (DAKO, Kyoto, Japan). The antibodies used were as follows: anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (1:300, G4.18, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (1:300, OX-8, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) and anti-CD79α polyclonal antibody (1:200, Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA). For antigen retrieval, deparaffinized sections were pretreated with an autoclave for 20 minutes at 121°C. For electron microscopic examination, small pieces of the formalin-fixed liver were re-fixed in glutaraldehyde fixative, post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide and then embedded in epoxy resin (Oken Shoji, Tokyo, Japan). Ultrathin sections were double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed under a JEM-100 CX II electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

The animal had no clinical signs or body weight change at 5 to 18 weeks of age. Paralytic gait and depression of body weight were noted at 19 weeks old. Hematologically, the white blood cell count was elevated markedly (377 × 102/μl) due to an increase in lymphocyte numbers, whereas the red blood cell count was mildly decreased (610 × 102/μl). In the examination of the blood smears, numerous lymphoid cells were intermingled with a few slightly large lymphocytes, but neither atypical nor blastic lymphocytes were detected.

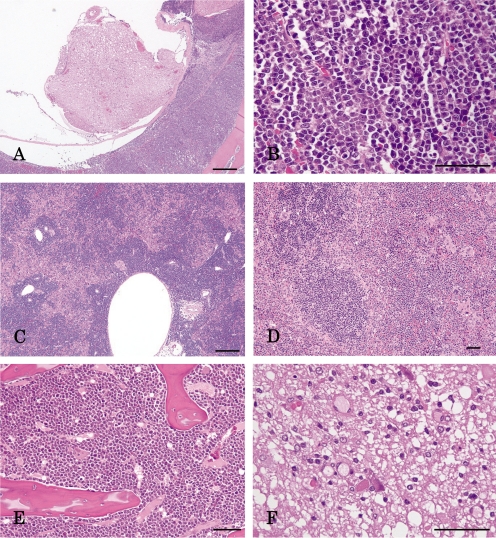

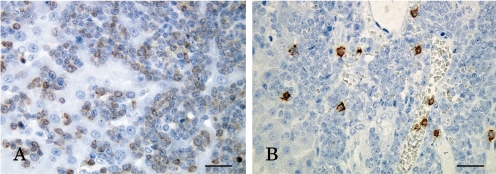

Macroscopically, the spleen and liver were markedly enlarged with dark red spots on their surfaces, and the thoracic spinal cord was partially atrophied. However, no remarkable changes were observed in the thymus and lymph nodes. Microscopically, neoplastic cells bearing round nuclei and scanty cytoplasm markedly infiltrated into the epidural space of the thoracic vertebra (Fig. 1A, B), liver (Fig. 1C), splenic red pulp (Fig. 1D) and sternal bone marrow (Fig. 1E) and their surrounding tissues. In addition, the thoracic spinal cord was partially compressed and degenerated due to epidural proliferation of the neoplastic cells (Fig. 1F). However, the lymph nodes, thymus and splenic white pulp were not involved. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells were prominently positive for CD3 (Fig. 2A), and some were positive for CD8 (Fig. 2B), whereas they were negative for CD79α in the liver.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs. A) The neoplastic cells markedly infiltrate into the epidural space of the thoracic vertebra and B) have a round nucleus and scanty cytoplasm. The neoplastic cells also infiltrate into C) the liver with more intensity in the portal triads, D) splenic red pulp with the white pulp remaining intact and E) sternal bone marrow. F) Degeneration of the spinal cord. HE staining. Bar=200 μm (A, C) or 50 μm (B, D, E, F).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemistry. The neoplastic cells were positive for A) CD3 and B) CD8 in the liver. Bar=20 μm.

Electron microscopically, the neoplastic cells had poorly-developed intracytoplasmic organelles. Neither granules suggestive of azurophil granules nor virus particles were observed in their cytoplasm.

Judging from the above-mentioned results, the present case was diagnosed as malignant T-cell lymphoma. However, the primary site of occurrence of this tumor was not clear. The lymphoid tissues, including the thymus, lymph nodes and splenic white pulp, were not involved in neoplastic cell proliferation and infiltration, although development of this type of tumor is generally considered to begin in the lymphoid tissues. In addition, a distinct tumor mass was not formed in any tissues in conjunction with neoplastic cell proliferation and infiltration.

As mentioned above, a few investigators 3 , 4 have reported spontaneous malignant T-cell lymphomas in young adult rats of the Long-Evans and Wistar strains. Our present case had similar to those described in characteristics these previous reports, including paralytic gait and neoplastic cell infiltration into the liver, spleen, sternal bone marrow and spinal cord, but no involvement of the thymus. However, in the case of Long-Evans rats, neoplastic cells affect some lymph nodes, resulting in formation of a tumor mass. On the other hand, malignant lymphomas induced by N-propyl-N-nitrosourea and N-methyl-N-nitrosourea 6 – 8 are known to originate from the thymus.

In the present paper, we described the pathological nature of a spontaneous malignant T-cell lymphoma accompanied by paralysis observed in a young adult Crl:CD (SD) rat. This report provides useful information for assessment of the results of toxicological studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Kunio Doi, Emeritus Professor of the University of Tokyo, for critical review of the manuscript. The authors also thank Mr. Pete Aughton, ITR Laboratories Canada Inc., for proofreading.

References

- 1. Stefanski SA, Elwell MR, Stromberg PC.Spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat. GA boorman, SL Eustis, MR Elewell, CA Montgomery Jr., and WF Mackenzie (eds). Academic Press, Inc. Sandiego, California. 369–393.1990.

- 2.Otova B, Sladka M, Damoiseaux J, Panczak A, Mandys V, Marinov I. Relevant animal model of human lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma—Spontaneous T-cell lymphomas in an inbred Sprague-Dawley rat strain (SD/Cub) Folia Biologica. 2002;48:213–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagamine CM, Jackson CN, Beck KA, Marini RP, Fox JG, Nambiar PR. Acute paraplegia in a young adult Long-Evans rat resulting from T-cell lymphoma. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2005;44:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashi S, Nonoyama T, Miyajima H. Spontaneous nonthymic T cell lymphomas in young Wister rats. Vet Pathol. 1989;26:326–332. doi: 10.1177/030098588902600407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Son WC, Gopinath C. Early occurrence of spontaneous tumors in CD-1 mice and Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Pathol. 2004;32:371–374. doi: 10.1080/01926230490440871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shisa H, Suzuki M. Action site of the gene determining susceptibility to propylnitrosourea-induced thymic lymphomas in F344 rats. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb01744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koestner AW, Ruecker FA, Koestner A. Morphology and pathogenesis of tumors of the thymus and stomach in Sprague-Dawley rats following intragastric administration of methyl nitrosourea (MNU) Int J Cancer. 1977;20:418–426. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva Franchi CA, Bacchi MM, Padovani CR, de Camargo JL. Thymic lymphomas in Wistar rats exposed to N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU) Cancer Sci. 2003;94:240–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]